Shifting the paradigm: the urgency to de-risk vaccine development

Estimates for the decade leading up to 2030 show that over approximately 50 million deaths could be averted through vaccinations against infectious diseases1. Globally, the demand for vaccines is growing due to several key drivers. First, new vaccines are needed to counter the increasing prevalence of potentially pandemic viral pathogens, as highlighted by the recent SARS-CoV-2 pandemic or the current m-pox outbreaks. This situation is compounded by the continuing emergence of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) which has been linked to 5 million deaths globally in 20192. This unprecedented emergence led the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and World Health Organization (WHO) to formulate a list of first-line targets mostly involved in nosocomial infections, the ‘ESKAPE’ pathogens—Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterobacter species3. Effective vaccines are also needed against residual unmet needs such as malaria, tuberculosis, and HIV/AIDS, and against pathogens associated with high impact and case fatality rates but with a locally restricted incidence, such as Marburg virus. Second, the rising vaccine demand is driven by global population growth and demographic shifts. Particularly in high- and middle-income countries (HICs and MICs, respectively) there is a steady increase in the population of older adults (OAs), which will make up nearly a quarter of the global population by 2050. Indeed, while the incidence and severity of infectious disease symptoms increases with age, only few vaccines are currently specifically targeted at the OA population4. In parallel, pediatric vaccine demands continue to grow, driven in part by the demographics of African countries. This has been a driver for GAVI’s aim to vaccinate a further 300 million children between 2021 and 20255. Third, across the age spectrum there is a growing awareness of the value of preventive healthcare and meeting the varying vaccine needs across a person’s life-span6. The mindset shift toward an increased focus on adult vaccination is illustrated by the WHO’s decision to make global life-course vaccination a strategic priority in their Immunization Agenda 2030, aiming to mirror the successful delivery of pediatric vaccines7. However, achieving optimal vaccine coverage is increasingly impeded by vaccine hesitancy, which has been listed in 2019 among the WHO’s top 10 global health threats8,9.

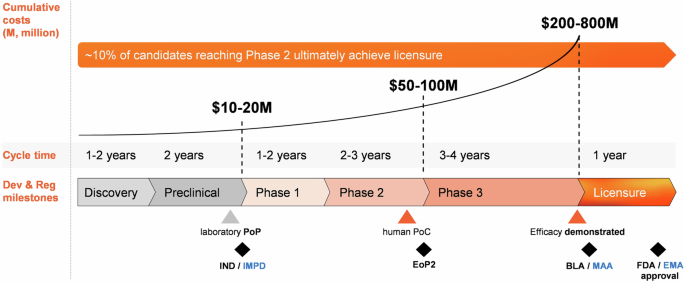

The health economic (HE) gain of vaccines will be mostly felt in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), due to their higher disease burden and less developed medical infrastructures. Indeed, with a return of investment of ~$20 per $1 spent on vaccination against 10 diseases prevalent in LMICs—which can be more than doubled when broader HE and social benefits are considered10— the impact of global vaccination cannot be underestimated. Yet, the standard approach to prophylactic vaccine development struggles to address the medical needs, with as root causes the long timelines from discovery/preclinical phases to licensure, spanning up to 15 years, and exceedingly high expenditures, with Phase 3 development accounting for ~70% of the total costs11,12,13 (Fig. 1). As R&D productivity is a function of the development time and costs for both successful and unsuccessful candidates, the price tag for developing one vaccine, adjusted for the costs of those failing in R&D, can amount to roughly $1 billion11,12,13. Throughout the process there is a high risk of failure, due to limitations posed by immunology/epidemiology (owing to specificities of the disease, target population, or availability of validated correlates of protection [CoPs] or of reactogenicity/safety biomarkers), technology (platforms and tools, production scale-up), execution, market (size, competitive landscape, strategic fit), regulatory stringency, and funding12. In addition, prelicensure clinical trials can detect the more common adverse events but can be limited in their capacity to detect certain rare adverse events, which may lead to a vaccine’s retraction from the market14,15. All in all, this state of affairs amounts to a slim (~10%12) probability of market entry for any candidate reaching clinical stages. While the number of new pharmaceuticals remained stable over the last three decades, the associated R&D costs have multiplied and became for many manufacturers increasingly difficult to afford. As a consequence, the number of investing vaccine manufacturers and overall investments have dwindled16. This imbalanced situation resulted in a mismatch between the investments and expected turn-over of a product (the ‘productivity gap’12).

Stages of traditional vaccine development are illustrated, along with average cycle times, high-level estimated costs, and key development and regulatory (Dev & Reg) milestones reached up to licensure (black symbols). Development starts with a ‘discovery’ phase (antigen identification/design and initial antigenicity and immunogenicity screening in small animal/in vitro models), followed by comprehensive preclinical immunogenicity and reactogenicity evaluations. These early ‘planning’ phases toward establishing a laboratory proof of principle (PoP) are relatively swift and low-cost, and can be followed by filing either an Investigational New Drug (IND) application with the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA; black font), or an Investigational Medicinal Product Dossier (IMPD) with the European Medicines Administration (EMA; blue font). Thereafter, data generation decelerates, and costs increase steeply, particularly in Phase 3 trials. The human proof of concept (PoC) represents a cornerstone in a vaccine’s development, as it triggers the go/no-go decisions on subsequent clinical phases. Discussion of the Phase 2 data occurs in End of Phase 2 (EoP2) meetings with the FDA or EMA, which set the basis for pivotal Phase 3 trials. When successful, a Biological License Application (BLA) or Marketing Authorization Application (MAA) can be submitted and eventually approved. Post licensure, bottlenecks in the ‘delivery’ path to commercialization include realizing market access, commercial-scale manufacturing, and post-marketing (Phase 4) studies to provide real-world evidence, and upkeeping the vaccine’s life-cycle management. The figure presents average timelines of the standard vaccine development phases based on published data (refs. 11,12,13).

Marking an abrupt break with the traditional development norms, the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic represented a cornerstone in vaccine R&D and sparked new opportunities for innovation. This watershed is underscored by the COVID-19 vaccines’ extraordinarily fast (9 months) progress from Phase 1 development start through regulatory approval, or the 3-month strain-switch development recently seen for certain mRNA COVID-19 vaccines17,18,19. The high pace was underpinned by the efficiency and scalability of nucleic-acid-based platforms (causing a surge in particularly mRNA vaccines), seamless clinical trial phases supported by real-world evidence, strong regulatory prioritization, and, importantly, the scientific/technological collaborations fostered by effective public-private partnerships (PPPs)17. Unfortunately, the post-pandemic drive for innovation has been manifested unevenly across disease areas and vaccine archetypes20. Indeed, while cutting-edge innovation aided the development of vaccines against seasonal diseases such as COVID-19, medium-level innovation was observed for persisting threats or potential outbreaks, such as respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and chikungunya virus (CHIKV), respectively, while innovation lagged behind for neglected tropical diseases (NTDs)—for which very few approved vaccines exist despite incentivizing initiatives21—and nosocomial pathogens. This situation has created a global vaccine inequity and profound public health challenges.

Besides public funding, de-risking and accelerating vaccine development remains crucial to close the productivity gap and address these disparities. By taking effective early-stage decisions and, if needed, by swiftly terminating the likely unsuccessful projects, fewer but more promising programs advance to the expensive later stages such that the proof-of-concept (PoC) is reached faster and at lower cost. This ‘quick-win, fast-fail’ paradigm requires switching a success-focused mindset toward a stronger focus on decreasing technical uncertainty before progressing to late-stage development22. Here, we illustrate on the basis of real-world examples how frontloading the risk in early development stages (preclinical and early clinical phases) can be leveraged to produce more innovative, cost-effective candidates with increased market potential. Moreover, by controlling R&D costs, these early de-risking strategies can incentivize an increased focus on the more challenging vaccine targets, to ultimately attain a more equitable and sustainable global access to life-saving vaccines.

Leveraging CoPs and biomarkers for early de-risking

Apart from clinical safety, which is beyond the scope of this article, clinical efficacy remains the first-choice endpoint to demonstrate vaccine performance and support licensure. However, demonstrating vaccine efficacy is in many cases unfeasible. This can be due to either a low or unpredictable disease incidence, an uncertain epidemiology (e.g. for Zika, Chikungunya, or mpox), or to the unattainability of adequate trial sample sizes as a result of already existing vaccines or standards of care. In these cases, an accepted CoP (an immune marker that mechanistically predicts protection against a specified clinical disease endpoint) can provide an alternative pathway to licensure. A CoP can also de-risk and reduce the size of late-stage clinical studies by supporting dose/regimen selections, pivotal data generation, and immuno-bridging between populations23. CoPs can be identified by analyzing immune response data from protected versus susceptible participants in effectiveness or immuno-epidemiological studies using a standardized and validated assay24,25,26, or through extrapolation from human or animal challenge studies27,28,29.

For example, in the case of meningococcal vaccine development, initial evidence came from seroepidemiological studies conducted in the United States30. These studies showed that the proportion of individuals with serum bactericidal activity (by serum bactericidal antibody [SBA] assay with exogenous complement) to meningococci of serogroups A, B, and C (MenA, MenB and MenC, respectively) was inversely related to disease incidence. Furthermore, during an outbreak of MenC disease in military recruits, the vast majority of cases occurred in individuals with low SBA titers against MenC (i.e. <1:4)30. Based on this evidence, this serological CoP served as basis for licensure of MenC conjugate vaccines, in the absence of efficacy data30. Following widespread use, clear SBA-based CoPs have been derived and the threshold extended to all meningococcal vaccines, including protein-based MenB vaccine31,32. The SBA assay was used throughout the entire vaccine development cycles for both polysaccharide conjugate vaccines targeting serogroups A, C, W, Y, and X, and protein-based MenB vaccines: in the preclinical screening of candidates for advancement to clinical studies, and in the clinical phases, in turn, to select the optimal formulation, generate an early PoC, and (when complemented with Phase 3 effectiveness data), to serve as basis for licensure33.

Furthermore, for pneumococcal vaccine development, an aggregate CoP (a serotype-specific IgG level of 0.20 μg/mL23) was established from a vaccine efficacy (VE) study of a heptavalent CRM197 pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7) in infants, and used as basis for licensure of the 13-valent vaccine in the US. Based on trials in different settings and populations, the CoP for infants was then updated to 0.35 μg/mL23. This consensus threshold was incorporated into the WHO guidance for licensure of higher-valency pneumococcal vaccines, which is informed by a candidate’s head-to-head performance versus PCV7.

Monoclonal antibodies have been used as substitutes of mechanistic CoPs for certain viral vaccines, e.g. the first approved maternal RSV vaccine, a prefusion F (PreF) antigen-based vaccine; reviewed in refs. 23,34. A trial in at-risk infants, evaluating an RSV fusion (F) protein-targeting monoclonal antibody (palivizumab), defined a neutralizing antibody (nAb) titer that was associated with protecting the infants against severe disease. This threshold was then used to assess maternal vaccine responses in a Phase 1 study evaluating the abovementioned PreF-based candidate in pregnant women, followed by modeling to identify the fold-rise in maternal nAb titers needed to confer protection to their infants. PoC was achieved when a post-hoc analysis of a Phase 2b study testing the unadjuvanted candidate revealed high-level ( ~ 90%) VE against severe RSV-associated lower respiratory tract disease, consistent with the nAb titers exceeding the palivizumab threshold in infants35. In 2023, the maternal vaccine was granted approval and market authorization from the FDA and EMA, respectively34.

Unfortunately, very few vaccines can rely on an accepted CoP, and the currently known CoPs are predominantly serological benchmarks, thus disregarding any contributions from mucosal and/or cell-mediated immunity (CMI)23,29. Compared to CoPs, biomarkers encompass a wider range of indicators including immune responses present pre- or post-vaccination, biological processes or disease states, and can be based on laboratory tests for a pre-specified target response such as CMI, or on mechanistic links to protection or reactogenicity23,36,37. For example, several biomarkers have linked innate signatures or the presence of a specific B cell subset at baseline, with reactogenicity38,39,40.

While having a weaker statistical basis than CoPs, biomarkers may enable de-risking by supporting PoC generation in early clinical phases and allowing efficient connections of preclinical and clinical data37. A case in point is the development of a live-attenuated vaccine against Chikungunya41,42 which has an unpredictable epidemiology with disease cases and outbreaks affecting over 100 countries. The combination of human seroepidemiological data with data from non-human primate (NHP) challenge studies allowed defining a surrogate which, in turn, propelled the vaccine’s clinical development up to Phase 3 studies and licensure (Fig. 2)43,44,45.

For certain pathogens, clinical vaccine efficacy trials are unfeasible due to a lack of predictable epidemiology, effective national circulation surveillance systems, and/or a validated correlate of protection (CoP). For chikungunya virus (CHIKV), seroepidemiological data from 2015 proved critical for vaccine development, indicating that baseline neutralizing antibody (nAb) titers >10 correlated in infants with protection against infection43. The graph represents nAb titers measured at enrollment and after 1 year in a CHIKV-endemic region, showing that all participants with symptomatic or subclinical infections (represented by red or blue ellipses, respectively) had baseline titers <10, whereas participants with titers >10 showed no clinical manifestations (dark/light gray shapes)43. Aided by this data, and co-funded by the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovation (CEPI) and EU Horizon 2020, a single-shot live-attenuated virus candidate was designed and evaluated preclinically and in a Phase 1 trial performed in 2018/201941,42. Passive transfer of human post-vaccination sera (with increasing titers) from a Phase 1 trial, to non-human primates (NHPs), and subsequent CHIKV challenge of these animals, strengthened the correlation between human nAb titers and protection against CHIKV-induced disease in NHPs, and helped establishing a serological surrogate of protection44. This surrogate was used as primary immunological endpoint in pivotal Phase 3 studies conducted in 2020–2022, and formed the basis for the vaccine’s FDA accelerated-approval status for at-risk adults in 2023. However, the FDA and CDC have recently recommended pausing the vaccine’s use in individuals 60 years of age and older pending safety evaluations based on post-marketing reports45, highlighting the importance of post-licensure safety monitoring. Currently, other CEPI-supported candidates have progressed to Phase 2/3 studies, of which a two-dose inactivated vaccine is the most advanced41,42. Created with BioRender.com.

Particularly when biomarkers are supported by mechanistic preclinical data, they can support a rapid advancement to Phase 1/2 studies, when de-risking is still a relatively quick ‘win’. Then, the marker may serve to validate antigens/adjuvants and platforms, and support early human PoC generation. However, broader use of biomarker or CoP data still faces several roadblocks, such as restrictive guidance on the level of evidence required for (regulatory) decision-making, and insufficient standardization of data-collection tools and assays23. Especially the latter issue has become more pressing given the increased use of ‘omics’ technologies and multi-parameter assessments for biomarker identification23,46,47.

Effective use of controlled human infection models (CHIMs) in clinical vaccine development: Shigella vaccines and RSV vaccines for OA

CHIMs represent another vital de-risking tool for obtaining an immunological association with protection for a given read-out27. Indeed, a CHIM study was instrumental in securing the FDA license for the inactivated oral cholera vaccine48. CHIM data also enabled the early clinical de-risking of another bacterial vaccine, namely the Generalized Modules for Membrane Antigens (GMMA)-based vaccine against shigellosis, a leading bacterial cause of diarrhea in young children (Fig. 3, left). A monovalent S. sonnei vaccine candidate based on engineered outer membrane vesicles exposing Shigella’s O-antigen (O-Ag) was tested in a Phase 2b CHIM study49. Although the candidate failed to demonstrate clinical efficacy in that study, the CHIM data indicated a link between anti-lipopolysaccharide antibody levels and protection against infection50. These results prompted a return to the design stage, and suggested that a higher amount of O-Ag per vaccine dose may be needed to achieve adequate protection. Subsequent development focused on a new GMMA candidate harboring a ten-fold higher amount of S. sonnei O-Ag (relative to protein and lipid A). The antigen was included in a four-component vaccine also containing GMMA from three S. flexneri serotypes (1b, 2a and 3a), all of which are highly prevalent in LMICs51,52. Preclinical results indicated that the humoral immunogenicity of the OAg-enriched candidate was significantly higher as compared to the original monovalent vaccine52, and this result was used as PoC to progress the new candidate into clinical development53.

Examples of using controlled human infection models (CHIMs) in vaccine R&D are presented. Left: The Generalized Modules for Membrane Antigens (GMMA)-based Shigella candidate was first designed as monovalent vaccine (1) and evaluated in preclinical (2) and Phase (Ph)1 and 2a studies. A Ph2b CHIM study49 did not show vaccine efficacy (VE), but suggested a link between anti-lipopolysaccharide (LPS) O-antigen (OAg)-specific antibody titers and protection (3) (graph adapted from ref. 51; titers in Elisa Units). This informed the design of an improved next-generation (next-gen) GMMA-based vaccine and further optimization into a quadrivalent candidate targeting S. sonnei and S. flexneri serotypes 1b, 2a, and 3a (4). Compared with optimized monovalent vaccines, the quadrivalent candidate elicited significantly higher titers across serotypes in mice (5) (graph adapted from ref. 52; geometric mean titers in Elisa Units/mL; **p < 0.01). This supported the proof-of-concept (PoC). Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) vaccine production was followed by a staged Ph1/2 study (6) conducted first in Europe53 and then, as age de-escalation study in shigellosis-endemic populations, in Kenya (NCT05073003). Right: Timeline represents the clinical development of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) prefusion (PreF) protein-based vaccines with available VE data and targeting older adults34. Initial development was propelled by Ph3 data for a recombinant protein (rec) F-based antigen resembling aspects of both PreF and post-fusion conformations. The Ph3 data indicated that the non-PreF conformation is not the preferred candidate, as prespecified VE endpoints were not met, and geometric mean ratios (GMRs) of neutralizing antibody (nAb) titers (1 month post-vaccination [post-vac] vs. baseline) were low; graph based on refs. 54,55,56. Subsequent Ph1/2 studies evaluated PreF-based vaccines which were adenovector-based (*; see below), non-adjuvanted (non-adj) or AS01-adjuvanted (adj) PreF rec-based, or mRNA-based58. Concurrently, a CHIM study of the adenovector-based vaccine showed VE and convincing GMR nAb titers55, supporting the PreF-based strategy. The correlation between VE and nAb titers informed selecting nAbs as Ph3 read-out55, aligning with interim analyses (IA; GMR nAb titers: 11–17) and final analyses of a CHIM study of the non-adj vaccine56,57. Collectively these studies helped move forward the VE evaluations of PreF-based vaccines, leading to approvals of three candidates by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). *Antigen modification (into adenovector/protein) in Ph2b59. Created with BioRender.com.

The development of RSV vaccines for OA represents another example of the importance of CHIM studies for de-risking late-stage clinical evaluations (Fig. 3, right). Results from a failed Phase 3 study combined with data from CHIM trials provided preliminary clinical evidence and a certain level of confidence in the optimal antigen conformation and localization of neutralizing epitopes54,55,56,57. This data facilitated the decision-making process on at-risk investments during Phase 2, and enhanced the probability of success of pivotal Phase 3 trials34,58,59,60.

Of note, CHIM studies have not proven equally useful across pathogens and populations61,62. For example, the RSV CHIM studies in young adults have been useful for the PoC demonstrations of the vaccines for OA, but the data were not fully generalizable to the OA target population (or, for that matter, to the pediatric target population for RSV vaccines). For example, when comparing the RSV CHIMS in young adults with the RSV trials in OA, differences existed in the main study endpoints (i.e., upper vs. lower respiratory tract infections, respectively), and in the level of immunocompetence of the respective study populations. Moreover, CHIM data generated in HICs may not be generalizable to LMICs due to variations in nutrition, genetics, and co-morbidities61,63. Thus, the selection of an ad-hoc trial population can have far-reaching results for development timelines, as detailed below.

Streamlining development by improving design and conduct of clinical trials

Especially for low-incidence diseases, Phase 3 studies can be hampered and made more complex by the large sample size needed for statistical VE demonstration in the general population, in particular when VE is the only possible endpoint. An opportunity to generate an early-stage PoC is to seek protection in an at-risk setting or in populations of at-risk individuals (‘enriched’ populations), and then extend the findings to a more general population. A typical example is the development of a vaccine against Staphylococcus aureus. This ‘ESKAPE’ pathogen3 is associated with skin and soft tissue infections and invasive/pulmonary disease in healthcare, community and military settings, and is globally the second leading pathogen for AMR-associated deaths2. Despite several attempts, all Staphylococcus aureus vaccine programs failed to show efficacy in large Phase 3 trials, despite promising immunogenicity results in preclinical and early clinical stages. This is likely caused by the lack of reliable animal models, the pathogen’s multiple immune evasion strategies, and a still unclear mechanism of protection. The inability to achieve early clinical PoC and the need for substantial investments to fund large efficacy studies ultimately resulted in a disinvestment by manufacturers in new Staphylococcus aureus vaccine programs. In this context, ‘reverse vaccine development’ represents a new paradigm64 in which the typical order of studies is reversed, by seeking the demonstration of efficacy (PoC) early in the process instead of in Phase 3, as well as in a high attack-rate population which may differ from the actual vaccine target population. This approach was applied to the Phase 2 evaluation of a five-component candidate Staphylococcus aureus vaccine performed in an ad hoc population of adults with Staphylococcus aureus-associated ongoing skin and soft tissue infections (NCT04420221). Though ultimately unsuccessful, the clinical development of this candidate has been lean ( ~ 600 subjects in total), reasonably inexpensive, and drastically shortened compared to classical development times. The data from the enriched population thus allowed the program’s advancement from preclinical stages to clinical futility (i.e., demonstrated to be unlikely to meet its goal of demonstrating VE) within only 4 years64,65. Remarkably, this condensed timeline was achieved despite the concurrent COVID-19 pandemic.

Another striking example is the Phase 3 trial of a COVID-19 vaccine in Brazil, conducted for the first time in a high-risk population of healthcare professionals taking care of COVID-19 patients66,67. In this case-driven trial, the expected force of infection was significantly higher in the enriched population than in the general population. This allowed using a smaller sample size for the pivotal Phase 3 study of the vaccine, which subsequently became part of the first wave of COVID-19 vaccines approved for the WHO Emergency Use listing. A risk of following this approach is that a very high force of infection can translate into a lower efficacy rate in the enriched versus the general population68,69. The origin of VE variations in different settings may be of a multifactorial nature, including contributions from coinfections, nutritional status, and/or social/economic factors, amongst others69.

Besides a short-tracked manufacturing phase and maximized regulatory prioritization, early pandemic vaccine development was also streamlined by adaptive trial designs and smart trial protocols. Master protocols such as the WHO’s SOLIDARITY protocol allowed evaluating several candidates in diverse populations simultaneously, and included shared control arms70. In such adaptive designs, disease rates in a candidate’s arm were compared with concurrently randomized arms of other candidates or controls. This informed a vaccine’s addition or removal from the trial, and resulted in faster advancement of the lead candidates. These protocols also adopted a seamless sequence of partially overlapping Phase 1, 2, and 3 trials17, if possible following a Bayesian design, as applied in a cross-industry collaboration71. Thus, while no shortcuts were taken in the clinical research of COVID-19 vaccines and trial sizes were not reduced17, these designs allowed the progression of VE and safety evaluations in a faster, more ethical manner, and in more participants as compared to traditional trials.

The increased use of interim data as a basis for regulatory review was another game-changer for pandemic vaccine R&D strategies. Indeed, in the decade preceding the pandemic, clinical development timelines for an FDA-approved vaccine amounted to 8 years, spread across seven trials of which at least two were pivotal VE trials72. While this could potentially be shortened in cases of a fast-track designation or rolling data submissions for expedited approval (e.g., FDA’s Emergency Use Authorization [EUA] or EMA’s Conditional Marketing Authorization [CMA]) as was applied to A/H1N1 pandemic vaccines, the more drastic accelerations did not occur until the pandemic. Then, regulators facilitated timelines of ~3 months for BLA approval, or 3 weeks for EUA/CMA applications based on interim Phase 3 results73,74,75,76, which were also used for the approval of real-world-evidence and Phase 4 studies. These achievements highlight the merit of adopting a strategic approach with a strong focus on early regulatory contacts.

Across all phases, artificial intelligence/machine learning (AI/ML) combined with high-dimensional data generation is increasingly recognized as the new frontier for fast-tracking and de-risking vaccine R&D77,78,79 (Fig. 4). This particularly applies when AI/ML is supported by innovative statistical approaches to optimize early and interim analyses of vaccine R&D data. Indeed, Bayesian statistics (which inherently incorporate uncertainty) and predictive modeling can significantly enhance such data analyses by providing a robust framework for managing uncertainty and integrating diverse information sources. These approaches allow incorporating prior knowledge—e.g. insights from previous studies, expert opinions, or biological data—into the analysis, and such historical data, underpinned by a deep immunological understanding, can then help guide the analyses of new data. Predictive models, especially those built using ML techniques, can forecast outcomes based on early and interim data. Especially Bayesian predictive models are powerful, as they quantify uncertainty in predictions, enabling more informed decisions on whether to continue, modify, or halt a trial. By deeply informing the decision-making process, these methods can lead to faster and safer vaccine development.

Figure represents a (non-exhaustive) list of examples of AI/ML-supported aspects across the development spectrum. In the discovery phase, such tools can provide an in silico platform for antigen discovery and design (e.g. by ‘reverse vaccinology’51), or, combined with systems biology techniques, characterize innate immune responses to adjuvants. In the preclinical phase, AI-informed immune networks for animal models support analyses of biomarker data, and when combined with molecular pathway data from ‘omics’ technologies, these methods can be used to characterize transcriptional/cellular signatures of vaccine responses, or identify molecular immunogenicity or protection correlates or immunological pathways. In clinical development, AI allows data mining and reutilization of (pooled) historic trial data in Bayesian frameworks, or running Phase 1 trials in AI-created virtual patients representing an actual vaccinee (digital twin) or a hypothetical patient. This can eventually reduce Phase 3 sample sizes, predict trial outcomes and aid in selecting new study populations. AI-generated data can also help select study sites by predicting where, when and in which population a next disease wave will hit. In filing, these technologies support the use of e-documents, e-signatures, one-click-submissions, and document/protocol writing, and during life-cycle management (LCM) they help to predict vaccine coverage or a pathogen’s geo-expansion, and to reanalyze real-world evidence (RWE). Created with BioRender.com.

Finally, FDA’s ‘animal rule’ represents a last resort for pathogens for which testing on humans is impractical or unethical, as it allows extrapolating human efficacy solely from well-characterized animal efficacy data. Currently this approach has only been adopted for licensed anthrax vaccines for post-exposure prophylaxis.

Conclusions and perspectives

To fulfill the growing demand for next-generation vaccines, including those against emerging pathogens and new indications, a multipronged de-risking approach is needed that can shift vaccine development towards a more streamlined and lower-risk process. While all development phases benefit from expanded use of digital technologies, particularly the clinical development stages can be de-risked by enhanced biomarker and CoP definitions, smart study protocols with streamlined (if possible CHIM-based) designs, and, if feasible, early alignment with regulators. The latter ensures that early on, integrated evidence plans are fit for purpose, and can support the vaccine’s licensure pathway as well as any subsequent recommendation stages. If a classical approach is clinically unfeasible, allocating the necessary resources in industry to address an otherwise unmet medical need will necessitate early assurance of the vaccine’s eligibility for the appropriate regulatory pathways, including guidance on how to navigate the prequalification. Such pathways can include FDA’s Accelerated Approval and LPAD (‘Limited Population Pathway for Antibacterial and Antifungal Drugs’) processes, which can be further streamlined by employing biomarkers, alternative correlates beyond the classical mechanistic CoPs, and/or simplified clinical development plans. If possible, another key strategy is improving manufacturability by selecting flexible platforms/technologies in the design phase, while applying the learnings from the pandemic era in relation to manufacture consistency across batches and sites in CMC processes17,80. Not only does this heighten pandemic preparedness, it will also facilitate market authorization and national immunization program (NIP) inclusion, as manufacturing efficiency, antigen adaptability, and the potential for combination vaccines are among the core criteria in regulatory decision-making81.

Deploying sustainable manufacturing capacity and delivery infrastructures in LMICs is also critical for tackling the vaccine inequity persisting across communities, sexes, and countries. A case in point is the global COVID-19 vaccine inequity. Indeed, only 60% and 20% of the number of vaccine doses given per 100 people in HICs (with all doses counted individually) were administered in LMICs or LICs, respectively (Aug 2024 data82), and LMICs were also the most likely to be affected by pandemic-related cancellations of other vaccinations83. While equitable vaccine access is increasingly considered in decision-making by HICs and supranational organizations84,85 (e.g. WHO’s Health Equity Assessment Toolkit), stronger commitment is required globally to ensure it is consistently used as criterion in regulatory reviews. These developments call for enhanced building of manufacturing and regulatory capacity, to ensure that clinical trials are globally authorized and conducted in a timely and equitable manner86. Currently, several international regulatory collaborations are dedicated to addressing this need87, including the African Vaccine Regulatory Forum and the International Coalition of Medicines Regulatory Authorities, for example.

Creating more incentives to develop vaccines with a low commercial value will also enhance vaccine equity, by allowing industry to better balance their portfolios between such high-risk projects and expected ‘blockbusters’ that sustain their R&D budgets. These budgets can also be nurtured by faster funding of the industry through public procurement/reimbursement (which can take 6 years from regulatory recommendation, or longer, in the EU88), to be accomplished by earlier negotiations across all NIP stakeholders including the industry. Overall, this situation calls for greater alignment and more collaboration across borders. This can be leveraged by strong PPPs, which have historically been instrumental in addressing two key bottlenecks for the industry: funding, and scientific (academic) support e.g. for experimental medicine studies exploring disease mechanisms. PPPs have supported critical higher-risk vaccine projects already in the pre-pandemic era—e.g. the world’s first malaria vaccine (RTS,S/AS01), the M72/AS01 tuberculosis vaccine, and Ebola and CHIKV vaccines—and the COVID-19 pandemic has propelled many new collaborations between industry and non-industry partners (academics, governments, and supranational organizations). A prime example is ‘Operation Warp Speed’, which provided a paradigm for efficient PPP collaboration. Other COVID-19 vaccine-related initiatives include the Beyond COVID-19 Monitoring Excellence (BeCOME) or the Safety Platform for Emergency Vaccines (SPEAC; Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations–Brighton Collaboration), focusing on post-marketing monitoring or standardization of safety reporting, respectively89,90. As the returns on investment for society can also be substantial for more challenging projects91, fostering globally-funded PPPs remains imperative to sustain the momentum for increased innovation after the pandemic. There is an urgent need to robustly fund and optimize adult-targeting NIPs to establish global life-course vaccination92, as adult immunization programs are considered highly effective investments for governments and healthcare providers, with returns to society of up to 19 times their investment85. This holds true in the post-COVID-19 era, as the investments in the associated infrastructures made during the pandemic did not result in inclusion of adult vaccinations in routine immunization schedules85, and vaccination coverage among adults remains mostly inadequate93.

Crucially, the urgent need to develop new vaccines should be balanced with ensuring their safety. According to the stringent protocols enforced by regulatory agencies, careful surveillance and evaluation of potential vaccine-related adverse events are maintained throughout the vaccine’s development phases, as well as post licensure. This is supported by ongoing research efforts to understand the mechanisms of action underlying CoPs as well as safety biomarkers, though such benchmarks are unlikely to replace actual pharmacovigilance studies. All such efforts call for ongoing transparency, e.g. by publishing safety testing protocols and evaluations, to maintain public confidence in vaccines and address vaccine hesitancy.

To conclude, the key elements of the ‘toolkit’ for expedited and de-risked vaccine R&D include the optimized identification and use of CoPs, biomarkers, CHIMs and AI/ML technologies, and robust support from PPPs and cross-industry collaborations. Collectively, these measures will significantly contribute to the global efforts to close the R&D productivity gap, in the path towards a more equitable global vaccine access and improved public health.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

-

Carter, A. et al. Modeling the impact of vaccination for the immunization Agenda 2030: deaths averted due to vaccination against 14 pathogens in 194 countries from 2021 to 2030. Vaccine 42, S28–S37 (2024).

-

Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet 399, 629–655 (2022).

-

De Oliveira, D. M. P. et al. Antimicrobial resistance in ESKAPE pathogens. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 33, e00181–00119 (2020).

-

Pollard, A. J. & Bijker, E. M. A guide to vaccinology: from basic principles to new developments. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 21, 83–100 (2021).

-

Gavi—the Vaccine Alliance. Global immunisation in 2023: 7 things you need to know. https://www.gavi.org/vaccineswork/global-immunisation-2023-7-things-you-need-know (2024).

-

Jones, C. H., Jenkins, M. P., Adam Williams, B., Welch, V. L. & True, J. M. Exploring the future adult vaccine landscape-crowded schedules and new dynamics. NPJ Vaccines 9, 27 (2024).

-

World Health Organization. Immunization agenda 2030: a global strategy to leave no one behind. https://www.who.int/teams/immunization-vaccines-and-biologicals/strategies/ia2030 (2020).

-

Acharya, S., Aechtner, T., Dhir, S. & Venaik, S. Vaccine hesitancy: a structured review from a behavioral perspective (2015–2022). Psychol. Health Med. 30, 119–147 (2025).

-

World Health Organization. Ten Threats to Global Health in 2019. https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019 (2019).

-

Sim, S. Y., Watts, E., Constenla, D., Brenzel, L. & Patenaude, B. N. Return on investment from immunization against 10 pathogens in 94 low- and middle-income countries, 2011-30. Health Aff. 39, 1343–1353 (2020).

-

Han, S. Clinical vaccine development. Clin. Exp. Vaccin. Res. 4, 46–53 (2015).

-

Pronker, E. S., Weenen, T. C., Commandeur, H., Claassen, E. H. & Osterhaus, A. D. Risk in vaccine research and development quantified. PLoS ONE 8, e57755 (2013).

-

Gouglas, D. et al. Estimating the cost of vaccine development against epidemic infectious diseases: a cost minimisation study. Lancet Glob. Health 6, e1386–e1396 (2018).

-

Salmon, D. A., Orenstein, W. A., Plotkin, S. A. & Chen, R. T. Funding postauthorization vaccine-safety science. N. Engl. J. Med. 391, 102–105 (2024).

-

Knipe, D. M., Levy, O., Fitzgerald, K. A. & Mühlberger, E. Ensuring vaccine safety. Science 370, 1274–1275 (2020).

-

World Health Organization. WHO releases first data on global vaccine market since COVID-19. https://www.who.int/news/item/09-11-2022-who-releases-first-data-on-global-vaccine-market-since-covid-19 (2022).

-

Kuter, B. J., Offit, P. A. & Poland, G. A. The development of COVID-19 vaccines in the United States: why and how so fast? Vaccine 39, 2491–2495 (2021).

-

Excler, J. L., Saville, M., Berkley, S. & Kim, J. H. Vaccine development for emerging infectious diseases. Nat. Med. 27, 591–600 (2021).

-

U. S. Food and Drug Administration. Updated COVID-19 Vaccines for Use in the United States Beginning in Fall 2024. https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/updated-covid-19-vaccines-use-united-states-beginning-fall-2024 (2024).

-

Sabow, A. et al. Beyond the pandemic: the next chapter of innovation in vaccines. McKinsey & Company. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/life-sciences/our-insights/beyond-the-pandemic-the-next-chapter-of-innovation-in-vaccines (2024).

-

Mukherjee, S. The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulatory response to combat neglected tropical diseases (NTDs): a review. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 17, e0011010 (2023).

-

Owens, P. K. et al. A decade of innovation in pharmaceutical R&D: the Chorus model. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 14, 17–28 (2015).

-

King, D. F. et al. Realising the potential of correlates of protection for vaccine development, licensure and use: short summary. NPJ Vaccines 9, 82 (2024).

-

White, C. J. et al. Modified cases of chickenpox after varicella vaccination: correlation of protection with antibody response. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. 11, 19–22 (1992).

-

Gilbert, P. B. et al. Immune correlates analysis of the mRNA-1273 COVID-19 vaccine efficacy clinical trial. Science 375, 43–50 (2022).

-

The FUTURE II Study Group. Quadrivalent Vaccine against Human Papillomavirus to Prevent High-Grade Cervical Lesions. NEJM 356, 1915–1927 (2007).

-

Laurens, M. B. Controlled human infection studies accelerate vaccine development. J. Infect. Dis. 231, 1112–1116 (2025).

-

Little, S. F. et al. Defining a serological correlate of protection in rabbits for a recombinant anthrax vaccine. Vaccine 22, 422–430 (2004).

-

Plotkin, S. A. Recent updates on correlates of vaccine-induced protection. Front. Immunol. 13, 1081107 (2022).

-

Goldschneider, I., Gotschlich, E. C. & Artenstein, M. S. Human immunity to the meningococcus. I. The role of humoral antibodies. J. Exp. Med. 129, 1307–1326 (1969).

-

Andrews, N., Borrow, R. & Miller, E. Validation of serological correlate of protection for meningococcal C conjugate vaccine by using efficacy estimates from postlicensure surveillance in England. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 10, 780–786 (2003).

-

Borrow, R. et al. Methods to evaluate the performance of a multicomponent meningococcal serogroup B vaccine. mSphere 10, e0089824 (2025).

-

Pizza, M., Bekkat-Berkani, R. & Rappuoli, R. Vaccines against meningococcal diseases. Microorganisms 8, 1521 (2020).

-

Ruckwardt, T. J. The road to approved vaccines for respiratory syncytial virus. NPJ Vaccines 8, 138 (2023).

-

Simões, E. A. F. et al. Prefusion F protein-based respiratory syncytial virus immunization in pregnancy. N. Engl. J. Med. 386, 1615–1626 (2022).

-

Weiner, J. et al. Characterization of potential biomarkers of reactogenicity of licensed antiviral vaccines: randomized controlled clinical trials conducted by the BIOVACSAFE consortium. Sci. Rep. 9, 20362 (2019).

-

Van Tilbeurgh, M. et al. Predictive markers of immunogenicity and efficacy for human vaccines. Vaccines 9, 579 (2021).

-

Pullen, R. H. et al. A predictive model of vaccine reactogenicity using data from an in vitro human innate immunity assay system. J. Immunol. 212, 904–916 (2024).

-

Burny, W. et al. Inflammatory parameters associated with systemic reactogenicity following vaccination with adjuvanted hepatitis B vaccines in humans. Vaccine 37, 2004–2015 (2019).

-

Sobolev, O. et al. Adjuvanted influenza-H1N1 vaccination reveals lymphoid signatures of age-dependent early responses and of clinical adverse events. Nat. Immunol. 17, 204–213 (2016).

-

Cherian, N. et al. Strategic considerations on developing a CHIKV vaccine and ensuring equitable access for countries in need. NPJ Vaccines 8, 123 (2023).

-

Principi, N. & Esposito, S. Development of vaccines against emerging mosquito-vectored arbovirus infections. Vaccines 12, 87 (2024).

-

Yoon, I. K. et al. High rate of subclinical chikungunya virus infection and association of neutralizing antibody with protection in a prospective cohort in the Philippines. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 9, e0003764 (2015).

-

Roques, P. et al. Effectiveness of CHIKV vaccine VLA1553 demonstrated by passive transfer of human sera. JCI Insight 7, e160173 (2022).

-

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA and CDC recommend pause in use of Ixchiq (Chikungunya Vaccine, Live) in individuals 60 years of age and older while postmarketing safety reports are investigated: FDA Safety Communication. https://www.fda.gov/safety/medical-product-safety-information/fda-and-cdc-recommend-pause-use-ixchiq-chikungunya-vaccine-live-individuals-60-years-age-and-older (2025).

-

Raeven, R. H. M., van Riet, E., Meiring, H. D., Metz, B. & Kersten, G. F. A. Systems vaccinology and big data in the vaccine development chain. Immunology 156, 33–46 (2019).

-

Nemes, E. et al. The quest for vaccine-induced immune correlates of protection against tuberculosis. Vaccin. Insights 1, 165–181 (2022).

-

Chen, W. H. et al. Single-dose Live Oral Cholera Vaccine CVD 103-HgR protects against human experimental infection with Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor. Clin. Infect. Dis. 62, 1329–1335 (2016).

-

Frenck, R. W. Jr. et al. Efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity of the Shigella sonnei 1790GAHB GMMA candidate vaccine: results from a phase 2b randomized, placebo-controlled challenge study in adults. EClinicalMedicine 39, 101076 (2021).

-

Conti, V. et al. Putative correlates of protection against shigellosis assessing immunomarkers across responses to S. sonnei investigational vaccine. NPJ Vaccines 9, 56 (2024).

-

Micoli, F., Nakakana, U. N. & Berlanda Scorza, F. Towards a four-component GMMA-based vaccine against Shigella. Vaccines 10, 328 (2022).

-

Rossi, O. et al. A next-generation GMMA-based vaccine candidate to fight shigellosis. NPJ Vaccines 8, 130 (2023).

-

Leroux-Roels, I. et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a 4-component generalized modules for membrane antigens Shigella vaccine in healthy European adults: randomized, phase 1/2 study. J. Infect. Dis. 230, e971–e984 (2024).

-

Novavax. Novavax announces topline RSV F vaccine data from two clinical trials in older adults. https://ir.novavax.com/2016-09-25-Novavax-Announces-Topline-RSV-F-Vaccine-Data-from-Two-Clinical-Trials-in-Older-Adults (2016).

-

Sadoff, J. et al. Prevention of respiratory syncytial virus infection in healthy adults by a single immunization of Ad26.RSV.preF in a human challenge study. J. Infect. Dis. 226, 396–406 (2022).

-

Schmoele-Thoma, B. et al. Vaccine efficacy in adults in a respiratory syncytial virus challenge study. N. Engl. J. Med. 386, 2377–2386 (2022).

-

Schmoele-Thoma, B. et al. Phase 1/2, first-in-human study of the safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of an RSV prefusion F-based subunit vaccine candidate. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 6, S970 (2019).

-

Ricco, M. et al. Efficacy of respiratory syncytial virus vaccination to prevent lower respiratory tract illness in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Vaccines 12, 500 (2024).

-

Falsey, A. R. et al. Efficacy and safety of an Ad26.RSV.preF-RSV preF protein vaccine in older adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 388, 609–620 (2023).

-

Schwarz, T. F. et al. Immunogenicity and safety following 1 dose of AS01E-adjuvanted respiratory syncytial virus prefusion F protein vaccine in older adults: a phase 3 trial. J. Infect. Dis. 230, e102–e110 (2024).

-

Cavaleri, M. et al. Fourth controlled human infection model (CHIM) meeting, CHIM regulatory issues, May 24, 2023. Biologicals 85, 101745 (2024).

-

Abo, Y. N. et al. Strategic and scientific contributions of human challenge trials for vaccine development: facts versus fantasy. Lancet Infect. Dis. 23, e533–e546 (2023).

-

Msusa, K. P., Rogalski-Salter, T., Mandi, H. & Clemens, R. Critical success factors for conducting human challenge trials for vaccine development in low- and middle-income countries. Vaccine 40, 1261–1270 (2022).

-

Bagnoli, F., Galgani, I., Vadivelu, V. K. & Phogat, S. Reverse development of vaccines against antimicrobial-resistant pathogens. NPJ Vaccines 9, 71 (2024).

-

Sauvat, L. et al. Vaccines and monoclonal antibodies to prevent healthcare-associated bacterial infections. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 37, e00160–00122 (2024).

-

Palacios, R. et al. Double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled Phase III clinical trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of treating healthcare professionals with the adsorbed COVID-19 (inactivated) vaccine manufactured by Sinovac – PROFISCOV: a structured summary of a study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 21, 853 (2020).

-

Palacios, R. et al. Efficacy and safety of a COVID-19 inactivated vaccine in healthcare professionals in Brazil: the PROFISCOV study. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3822780 (2021).

-

World Health Organization. Background document on the inactivated vaccine Sinovac-CoronaVac against COVID-19: background document to the WHO Interim recommendations for use of the inactivated COVID-19 vaccine, CoronaVac, developed by Sinovac. World Health Organization. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/341455 (2021).

-

Kaslow, D. C. Force of infection: a determinant of vaccine efficacy? NPJ Vaccines 6, 51 (2021).

-

Liu, M., Li, Q., Lin, J., Lin, Y. & Hoffman, E. Innovative trial designs and analyses for vaccine clinical development. Contemp. Clin. Trials 100, 106225 (2021).

-

Senn, S. The design and analysis of vaccine trials for COVID-19 for the purpose of estimating efficacy. Pharm. Stat. 21, 790–807 (2022).

-

Puthumana, J., Egilman, A. C., Zhang, A. D., Schwartz, J. L. & Ross, J. S. Speed, evidence, and safety characteristics of vaccine approvals by the US Food and Drug Administration. JAMA Intern. Med. 181, 559–560 (2021).

-

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. BLA Clinical Review Memo, August 23, 2021 – COMIRNATY. https://www.fda.gov/media/152256/download (2021).

-

Wong, J. C., Lao, C. T., Yousif, M. M. & Luga, J. M. Fast tracking-vaccine safety, efficacy, and lessons learned: a narrative review. Vaccines10, 1256 (2022).

-

Kalinke, U. et al. Clinical development and approval of COVID-19 vaccines. Expert Rev. Vaccines 21, 609–619 (2022).

-

Joffe, S. et al. Data and safety monitoring of COVID-19 vaccine clinical trials. J. Infect. Dis. 224, 1995–2000 (2021).

-

Wong, F., de la Fuente-Nunez, C. & Collins, J. J. Leveraging artificial intelligence in the fight against infectious diseases. Science 381, 164–170 (2023).

-

Jin, M., Li, Q. & Kaur, A. Bayesian design for pediatric clinical trials with binary endpoints when borrowing historical information of treatment effect. Ther. Innov. Regul. Sci. 55, 360–369 (2021).

-

Olawade, D. B. et al. Leveraging artificial intelligence in vaccine development: A narrative review. J. Microbiol. Methods 224, 106998 (2024).

-

Warne, N. et al. Delivering 3 billion doses of Comirnaty in 2021. Nat. Biotechnol. 41, 183–188 (2023).

-

Buck, P. O. et al. New vaccine platforms-Novel dimensions of economic and societal value and their measurement. Vaccines12, 234 (2024).

-

Mathieu, E. et al. Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19). https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus (2020).

-

Ferranna, M. Causes and costs of global COVID-19 vaccine inequity. Semin. Immunopathol. 45, 469–480 (2024).

-

Ismail, S. J. et al. A framework for the systematic consideration of ethics, equity, feasibility, and acceptability in vaccine program recommendations. Vaccine 38, 5861–5876 (2020).

-

El Banhawi, H. et al. Socio-economic value of adult immunisation programmes. Office of Health Economics Contract Research Report. https://www.ohe.org/publications/the-socio-economic-value-of-adult-immunisation-programmes/ (2024).

-

Wellcome Trust. COVID-19 vaccines: the factors that enabled unprecedented timelines for clinical development and regulatory authorisation. https://cms.wellcome.org/sites/default/files/2022-03/unprecedented-timelines-covid19-vaccine-clinical-development-authorisation.pdf (2022).

-

Cavaleri, M. et al. A roadmap for fostering timely regulatory and ethics approvals of international clinical trials in support of global health research systems. Lancet Glob. Health 13, e769–e777 (2025).

-

Laigle, V. et al. Vaccine market access pathways in the EU27 and the United Kingdom-analysis and recommendations for improvements. Vaccine 39, 5706–5718 (2021).

-

Brighton Collaboration. Safety Platform for Emergency vACcines (SPEAC). https://brightoncollaboration.us/speac/ (2022).

-

Bauchau, V. et al. Multi-stakeholder call to action for the future of vaccine post-marketing monitoring: proceedings from the first beyond COVID-19 monitoring excellence (BeCOME) conference. Drug Saf. 48, 577–585 (2025).

-

Tortorice, D., Rappuoli, R. & Bloom, D. E. The economic case for scaling up health research and development: lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2321978121 (2024).

-

Doherty, T. M., Di Pasquale, A., Finnegan, G., Lele, J. & Philip, R. K. Sustaining the momentum for adult vaccination post-COVID-19 to leverage the global uptake of life-course immunisation: a scoping review and call to action. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 142, 106963 (2024).

-

Doherty, T. M., Ecarnot, F., Gaillat, J. & Privor-Dumm, L. Nonstructural barriers to adult vaccination. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 20, 2334475 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ellen Oe (GSK) for scientific writing services and Monica Guerrieri (GSK) for publication management and coordination. Glaxo Smith Kline Biologicals SA was the sponsor and took in charge all costs associated with the present manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

All authors are or were employees of the GSK and hold financial equities in GSK.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Masignani, V., Palacios, R., Martin, MT. et al. De-risking vaccine development: lessons, challenges, and prospects. npj Vaccines 10, 177 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41541-025-01211-z

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41541-025-01211-z