Main

Affinity reagents—molecules that bind to a target protein of interest—are critical as basic research tools for measuring or tracking biomolecules1, as probes for studying biological regulation through induced proximity2, as core elements of diagnostics3 and as therapeutics, such as neutralizing antibodies and antibody–drug conjugates4. However, even for very well-studied organisms, including Homo sapiens, antibody-based binders do not exist for many proteins of interest and, when available, are notorious for heterogenous quality control, function and specificity5.

Binders can be developed by generating antibodies to a target of interest through animal immunization, molecular display methods or by computational design6. Immunization-mediated binder generation typically costs thousands of dollars, takes many months and is limited to creating antibody-based reagents6. In vitro selection approaches, such as display-based methods (for example, phage display, messenger RNA (mRNA) display), cell sorting methods (for example, fluorescent or magnetic activated cell sorting) and growth-based methods (for example, bacterial-two-hybrid selections) can be used to mine high-diversity libraries of protein variants to identify binders to a target of interest7,8,9,10,11. However, these selection-based methods take several months to complete, primarily due to high false positive rates necessitating time-consuming secondary screening12,13,14. Reflecting this bottleneck, several high-throughput (104–105 variants) screening methods15,16,17 have been developed that are capable of testing each variant in the output of display and/or sorting selections; however, even these require substantial additional resources due to the need to clone putative hits into the new platform and the costs associated with high-throughput next-generation sequencing (NGS). Finally, while improving, computational design approaches require substantial computing capacities, expertise and subsequent display-based selections, affinity maturation and/or screening18,19.

Creating a novel binder to a protein generally requires months of highly specialized work, thousands of dollars, and often results in failure. Collectively, the costs and time associated with protein binder generation restrict production to laboratories with a central focus and expertise in these techniques, prohibiting exploratory work. In comparison, creating selective binders to DNA or RNA is as simple as designing complementary oligos, which can be synthesized and delivered in a matter of days for roughly US $10. The programmable nature of nucleic acid binders has led to the rapid explosion of diverse CRISPR technologies and other genetic tools. To address the critical bottleneck in protein binder discovery, we sought to develop a platform that can identify novel binders to protein targets of interest in a matter of days with high fidelity, has the capacity to perform multiplexed screens and is robust enough to be a routine research tool. Such a platform would both accelerate and democratize the binder discovery process.

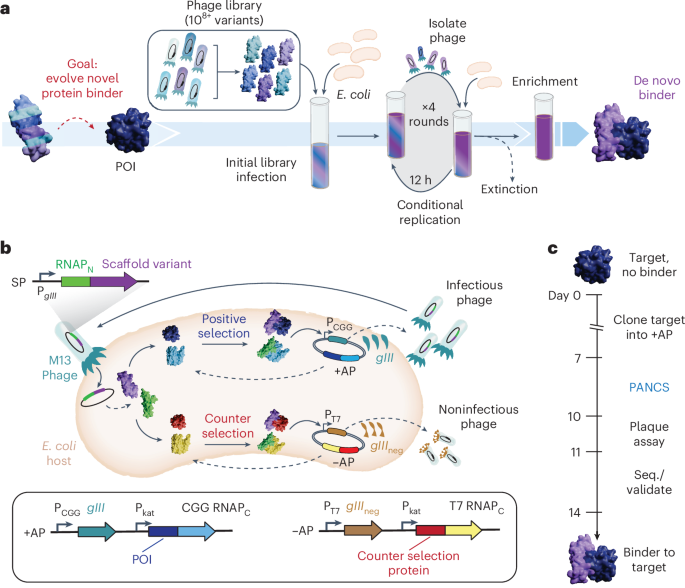

In this work, we establish phage-assisted noncontinuous selection of protein binders (PANCS-Binders; Fig. 1a), a viral life cycle-based selection platform that can comprehensively screen high-diversity (1010+) libraries of M13 phage-encoded protein variants and identify binders to panels of dozens or more proteins of interest in a matter of days. PANCS-Binders uses replication-deficient phage that encode protein variant libraries tagged with one half of a proximity-dependent split RNA polymerase (RNAPN) biosensor (Fig. 1b)20. Escherichia coli host cells are engineered to express a target protein of interest tagged with the other half of the split RNA polymerase (RNAPC). Protein–protein interaction (PPI) between a phage-encoded variant and the target reconstitutes the RNA polymerase (RNAP) and triggers expression of a required phage gene, allowing phage encoding that variant to replicate, in line with the conceptual principles of phage-assisted continuous evolution (PACE)21,22. After optimization and trial selections, we demonstrated the versatility of PANCS-Binders by performing selections on 95 different protein targets with two de novo phage-encoded protein variant libraries, each encoding ~108 unique protein variants, thereby completing 190 independent selections in 2 days. The hit rate of this screen was 55%, resulting in new binders for 52 diverse targets. We scaled up our library size 100-fold (~1010), which expanded the hit rate to 72% and dramatically improved the affinity of hits from PANCS: a 40–2,000× improvement with affinities as low as 206 pM. Additionally, we showcased how hits can be quickly affinity matured through PACE, resulting in >20 times improvement in affinity (to 8.4 nM). Finally, we demonstrated that the binders for two targets, Mdm2 and KRAS, engage their targets in mammalian cells: our Mdm2 binders inhibit the Mdm2-p53 interaction and fusion of our KRAS binder with an LIR motif leads to LC3B mediated degradation of endogenous KRAS23. We anticipate that the ease-of-use, speed and reliability of PANCS-Binders could facilitate a transition of binder generation from an expensive specialty requiring months of work with high failure to a laboratory method requiring less than 2 weeks of work, unlocking new potential in proteome targeting (Fig. 1c).

a, Schematic of the PANCS-Binders process. Serial passaging of de novo, high-diversity libraries of protein variants encoded in phage for the rapid discovery of binding variants via conditional phage replication on an E. coli selection strain. Selections include the extinction of inactive variants and enrichment of the active variants. POI, protein of interest. b, Schematic of the PANCS-Binders molecular biology. A split RNAP biosensor is used for in vivo selection of binder variants. gIII is removed from the M13 phage and placed on the positive selection plasmid (+AP) under the control of the CGG RNAP promoter. Phage encode the N-terminal portion of the split RNAP (RNAPN) fused to a protein variant (potential binder). The +AP encodes the target fused to the C-terminal portion of CGG RNAP (CGG RNAPC) expressed from a constitutive promoter (Pkat). If the binder variant interacts with the target, then RNAPN and RNAPC recombine and transcribe gIII from the CGG promoter (PCGG). A simultaneous counterselection is performed using a negative selection plasmid (−AP). The −AP encodes an off-target protein fused to an orthogonal T7 RNAPC. If the binder variant interacts with the off-target or RNAPC, then the RNAPN and RNAPC recombine and transcribe gIIIneg from the T7 promoter (PT7): a dominant negative variant of gIII that poisons phage amplification by preventing release of phage from the E. coli host. c, Timeline for 2-week binder discovery using PANCS-Binders: clone the desired target(s) into a +AP(s) and construct the selection strain, 4–6 passages over 2–3 days of PANCS, a plaque assay or qPCR to assess endpoint titer and then subcloning and sequencing (seq.) to validate specific enriched variants.

Results

Optimizing PANCS-Binders

Recently, we established a split RNAP-based PPI-PACE platform for reprogramming the binding specificity of proteins24 (Fig. 1b), which we demonstrated could swap the binding specificity of BCL2 and MCL1 using continuous evolution. In general, PACE has been shown to be powerful for altering or tuning existing functions of molecules25,26,27,28, primarily from initial variants with minimal or closely related function, rather than de novo discovery of function. We aimed to adapt the components of our PPI-PACE platform for the use of mining high-diversity libraries for de novo discovery of binders. To accomplish this, we cloned a phage-encoded, RNAPN-tagged 108 unique variant affibody library29 (Extended Data Fig. 1). We then performed PACE with this library on two targets, the RAS binding domain of RAF (RAF) and interferon-gamma (IFNG) (see Supplementary Table 3 for target details). Both evolutions went extinct (Extended Data Fig. 2a). Previous efforts have established that PACE can enrich active phage from pools of inactive phage (1:1,000 active-to-inactive ratio)22,28; however, de novo libraries are likely to have an active-to-inactive ratio closer to 1:107+. To assess if the PACE evolution process itself led to phage extinction (as opposed to no binders being present in our library), we constructed a mock library selection system that included known, active variants. We performed PACS (phage-assisted continuous selection22), PACE without the mutagenesis plasmid, using KRAS as a protein target (positive selection plasmid or +AP) and a mock library of containing a mixture of active phage encoding RAF that binds KRAS and inactive phage encoding an affitin, evolved to bind SasA, that does not bind KRAS30 (Fig. 2a). From these mock selections, we found that PPI-PACS could successfully enrich active phage from mock libraries of 1:105 (active:inactive phage; Extended Data Fig. 2b), but failed to do so at any lower ratio (1:106–9). This indicates that continuous selection does not sample every variant in the mock library in the initial infection step. PANCE, noncontinuous passaging, has frequently been used as a less stringent version of PACE, and we suspected that part of this lower stringency could be due to a higher percentage of phage that infect cells before being washed away in the continuous flow versus in passaging31,32. We hypothesized that by extending the incubation time of phage with selection cells, we could more completely sample every variant in our de novo library and therefore succeed in de novo selections.

a, The selection system for mock libraries consists of an E. coli selection strain with KRAS4b (WT)-RNAPC,CGG as the positive selection target (+AP) and ZBneg-RNAPC,T7 as the counterselection target (−AP). The mock library consisted of a mixture of two selection plasmids (SP): an active phage with RNAPN-RAF(RBD) and an inactive phage with RNAPN-Affitin (SasA). b, Phage amplification assay: 1,000 PFU of each phage are incubated with 1 ml of a selection strain for 12 h and then the titer is determined. The amplification rate is output titer/input titer. c, Amplification rate for RAF variants and the nonbinding affitin (SasA) phage on the KRAS selection strain. Published affinities (Kd) are listed above each RAF variant amplification rate47. Each amplification rate was obtained in duplicate and error bars indicate mean ± s.d. The green line indicates an amplification rate of 20 (no enrichment if passaging at 5%) and the red line indicates an amplification rate of 1 (no amplification). d, Four-passage PANCS starting from a mock library (10 PFU active phage with 1010 PFU inactive phage (affitin (SasA)) in 5 ml of KRAS4b (WT) selection strain (Fig. 2a) with a 12 h of passage outgrowth and 5% transfer of supernatant phage into fresh cells to seed each passage. e, Titers at the end of each passage (passage 0 indicates the initial titer to start PANCS). The limit of detection in our plaque assays is 5 × 102 PFU ml−1 (1 PFU); if a titer had 0 PFU, it was set to 0.2 PFU for calculation purposes (Non-Binder Affitin (SasA) in Fig. 2c). Each phage was passaged in triplicate (n = 3) and error bars indicate mean ± s.d.

To test this hypothesis, we optimized a noncontinuous selection procedure. First, we established 6 h as a minimum time for incubating phage and cells to obtain nearly complete infection of our phage sample by monitoring the rate at which phage infect our cells (Supplementary Fig. 1); 12-hour incubations were chosen for convenience. To determine how quickly active phage would enrich and how quickly inactive phage would de-enrich, we measured the rate of amplification for active (RAF variants with known affinities) and inactive phage (Affitin (SasA)) in a KRAS selection strain (Fig. 2a,b). The amplification rates spanned eight orders of magnitude: 106 for high affinity WT RAF, 101–2 for low affinity RAF mutants and 10−1–2 for nonbinders (Fig. 2c).

Based on the replication rates, we predicted that serial passaging with 5% of phage transferred between passages would result in selective enrichment of the high affinity WT RAF from 10 phage to >109 phage in just two passages and the complete de-enrichment of the inactive phage from 109 to 0 in just four passages (Supplementary Fig. 2). We tested this prediction by passaging mock libraries of 10 phage of each RAF variant spiked into 1010 inactive Affitin (SasA) phage (Fig. 2d). As expected, over 2 days, the high affinity WT RAF variant enriched (a >1015-fold relative enrichment) during the four-passage selection; all weaker binders and inactive phage went extinct (Fig. 2e). We performed additional mock PANCS to understand the effects of several variables on this relative enrichment rate: +AP selection stringency (Supplementary Fig. 3), transfer rate (Supplementary Fig. 4), −AP selection stringency (Supplementary Fig. 5) and initial cell-to-phage ratio (Supplementary Fig. 6). Finally, we tested mock selections using several published binder–target pairs using our optimized AP strengths, transfer rate and initial cell-to-phage ratios (Extended Data Fig. 3). Collectively, these mock selections indicate that this new system, which we named PANCS-Binders, could perform de novo selections of up to 1010+ variant libraries (above the typical 109–10 E. coli transformation limit) in 2 days, using simple serial phage outgrowths in culture tubes or even 96-well plates. Therefore, we next performed pilot selections with a de novo phage-encoded binder library to assess whether PANCS-Binders can be used to discover novel binders.

Pilot de novo library PANCS-Binders

We selected six protein targets to attempt to discover novel binders for, each with varying architectures and degrees of structural order: KRAS4b(G12D), RAF (RBD), Mdm2 (1-188), IFNG, Myc DNA binding domain and Sos1 disordered domain (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Table 3). We simply cloned each target into the +AP as a RNAPC fusion and transformed into E. coli host cells with the ZBneg −AP used in our final mock selections (Extended Data Fig. 3) to prepare the selection materials. In this case, the counterselection protein was chosen only to select against RNAPc binding variants. We passaged the 108 affibody library (Extended Data Fig. 1), which had gone extinct in PACE-based selections (Extended Data Fig. 2a), on each E. coli selection strain in culture tubes for 12-h outgrowths and 5% transfer between passages (Fig. 3a). After four rounds of passaging (48 h total), we measured the titer in each condition. KRAS(G12D), RAF (RBD), IFNG and Mdm2 had high titers (>108), indicating successful selections, while Sos1 and Myc (DNA binding domain) selections had titers near the limit of detection (<105), indicating failure to enrich binders (Supplementary Table 4).

a, Cloning target +AP panel, transformation of selection strains, parallel four-passage PANCS of each selection strain with a 108 variant affibody library. Titer assessed after the fourth passage. Selections are indicated as AlphaFold predictions of the binder–target pair (if titer was high) or target alone (if titer was low: see Supplementary Table 4 for titers). The affibody sequence from passage four phage was PCR amplified for NGS and subcloned into a luciferase assay system (shown bottom right) and pET vectors for protein purification for SPR. Binding validation luciferase assay (bottom right), the target is fused to the RNAPC, the binder is fused to the RNAPN and LuxAB expression is determined by PPI-dependent recombination of the split RNAP (spRNAP). b, Dominant amino acid sequences identified from the NGS (top) and the percentage of reads for each variant in the NGS of passage four (bottom left). Variants shown in color with the associated sequence were examined further in the luciferase and SPR assays. For the luciferase assay, each condition has an n of 4 (a single measurement from four independent cultures) and error bars indicate mean ± s.d. The second S-WYS variant for Mdm2 isolated for testing in lux (pink) did not have a single read in the NGS but is indicated as having a single read for plotting on a log scale. Fold change in luciferase signal (bottom right) for select variants over the template affibody for the library (nonbinder), and when available, published binders to these targets (NS1 Monobody (70 nM Kd from ref. 34, Z(RAF322) affibody (190 nM Kd, ref. 33), Cl2-based-binder (Kd not determined35). The in vitro binding affinity, Kd, is reported for select variants (measured by SPR, Supplementary Fig. 11). lum., luminescence. c, Read percentage for each unique variant in the original PANCS compared to a biological replicate of the PANCS at passage four (comparison of parallel replicates in Extended Data Fig. 4). If a variant was present in one NGS sample but not in another, it was coded as 0.01% of reads. Pearson correlation coefficients are reported in Supplementary Table 5.

We performed NGS on the four selections with a high titer (Fig. 3b), which revealed that the selections on KRAS(G12D), RAF (RBD) and IFNG each converged onto a single sequence (that is, >80% of reads belonged to that sequence). The most dominant Mdm2 variant comprised only 2.6% of the population; in retrospect, this lack of convergence is unsurprising as Mdm2 binds an FXXXWF/Y motif common to ~3% of library variants and, therefore, many variants were enriched. For KRAS G12D, RAF (RBD) and IFNG selections, we also sequenced the library, passage 2 and passage 3, which revealed that the relative ratio between active variants is set by passage 2 (Supplementary Fig. 7), in line with our mock PANCS results. Finally, we used AlphaFold3 to predict the binding interface for each hit, which, as expected, showed the randomized region of the affibody at the predicted interaction interface (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 8).

We subcloned the top variants from each selection (those >1% of reads in KRAS G12D, RAF (RBD) and IFNG selections and four random variants from the Mdm2 selection) into an expression plasmid (Lux-N) for measuring binding in a previously established E. coli luciferase assay20,22,24 (Fig. 3a). Reconstitution of the proximity-dependent split RNAP, measured by the production of luminescence, was observed to be induced following coexpression of each affibody variant and its respective selection target. This indicated variant–target binding in E. coli (Fig. 3b). Positive binding controls, previously published binders discovered by ribosome display (Z(RAF322)33, phage display (NS1 Monobody)34 and rational engineering (Cl2 12.1A)35, produced comparable signal to the newly selected affibodies for RAF (RBD), KRAS G12D and Mdm2, respectively. We confirmed that a subset of these binders specifically bound their target, in that these binders did not show general binding with the four targets that gave hits, but only with the target they were selected on (Supplementary Fig. 9; only S-VVD had weak off-target binding to Mdm2) indicating that binding was to the target rather than to the RNAPc or a more general nonspecific binding such as induced aggregation. We purified each of the top binders (Supplementary Fig. 10) and performed surface-plasmon resonance (SPR) binding assays, revealing binding between top variants and their target of interest with dissociation constants ranging between 176 and 635 nM (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 11). These results confirmed that the selections successfully enriched binder variants.

To assess reproducibility of the selections, we repeated the entire six-target selection four additional times in parallel several months later. This yielded highly consistent results in terms of the extinction events and endpoint phage titers (Extended Data Fig. 4a). We performed NGS on each of the replicate selections and observed high reproducibility (r = 0.72; average of each pairwise Pearson’s correlation for variants >0.1% of NGS reads; variants enriched >5% were identical) between biological replicates (Fig. 3c) and within parallel replicates (Extended Data Fig. 4b; r = 0.95; each pairwise Pearson’s correlation coefficient is reported in Supplementary Table 5). These results demonstrate that PANCS-Binders can rapidly, in just 48 h, comprehensively and reproducibly screen and isolate binder variants from de novo libraries without the need for replicates or additional screening.

High-throughput PANCS

We next sought to challenge the PANCS-Binders technology in a multiplexed high-throughput selection by attempting to simultaneously identify binders for a large panel of diverse protein targets in 96-well plate format (Fig. 4a). In addition to scaling down the selection volumes to 1 ml for plate compatibility, we made three additional adjustments for this selection: we extended the linker length between the target and RNAPC to ensure that the position and orientation of the binder was not constrained (Supplementary Fig. 12), we reduced the selection stringency from 5 to 10% transfer, and we created a second ~108 phage library based on an affitin scaffold to have two different scaffold libraries to compare to one another (Extended Data Fig. 5).

a, Cloning a 96-panel set of target selection strains, 96-deep well plate-based parallel PANCS-Binders selection of two 108 libraries (affibody (Extended Data Fig. 1) and affitin (Extended Data Fig. 5)) using binding assays and qPCR to measure the endpoint titer in a high-throughput manner. b, E. coli spRNAP complementation luciferase assay heatmap (Fig. 3a) on all preliminary hit variants (titer >107 PFU ml−1 when the top variant is full-length protein (see Supplementary Note 1 in the Supplementary Information and Supplementary Fig. 14 for individual plots). Fold change in binding >20 is set equal to 20; selections that were not preliminary hits are indicated in gray. c, Fold change in luciferase signal for selection of 16 variants from the de novo screens assessed across 16 targets and additional controls to assess selectivity. Within each target (y axis) each binder is normalized to the signal for two nonbinders (set to 1): an affibody that was evolved to bind PDL1 (ref. 48) and an affitin that was evolved to bind SasA30. Only one off-diagonal had a fold change >2.

We cloned a randomly chosen collection of proteins of interest (a total of 95 targets) into +APs without additional optimization, as well as a negative control no-fusion +AP consisting of a start codon followed by the 60-amino acid GS linker and RNAPc, to establish a 96-well plate of target selection strains. The 95 targets (Supplementary Table 3) vary in origin (mammalian (76), bacterial (14), viral (two), or other (three)), localization (secreted (11), extracellular domains of membrane proteins (14), full-length membrane proteins (five), cytosolic (44) or nuclear (21)), function (E3 ligases, kinases, phosphatases, de-ubiquitinates, proteases, inhibitory proteins, transcription factors, receptors, GTPases and so on) and structure (fully ordered (63), large disordered regions (16), fully disordered (16)). In total, 24 targets have previously published synthetic binding proteins36 (each indicated in Supplementary Table 3). Forty targets were full-length antigens and 55 were partial antigens and/or select domains. We reasoned that such a diverse target panel should assess the capability for performing PANCS-Binders in a high-throughput manner and provide a realistic estimate of the expected hit rate for 108 libraries. To confirm that the selection +APs were expressed in E. coli, we performed an amplification assay (Extended Data Fig. 6) with phage encoding RNAPN WT, which is not proximity dependent (recombines with RNAPC independent of target and binder interacting), with the −AP (demonstrating sufficient counterselection to prevent nonselective replication) and without the −AP (indicating sufficient target expression for binding induced replication; only four targets did not amplify more than tenfold). Notably, this panel has many targets that are difficult to purify from E. coli, which highlights the superior properties of targets expressed from plasmids over in vitro purification and selection methods.

After preparing the selection cells, we performed the four-passage PANCS-Binders over the course of 48 h and collected endpoint titers using quantitative PCR (qPCR) to identify preliminary hits: titers of >107 plaque forming units per ml (PFU ml−1) (Extended Data Fig. 7 and Supplementary Table 6; see Supplementary Note 1 for a detailed discussion of how we selected this threshold including Supplementary Figs. 13–17). For all preliminary hit selections, we collected NGS, performed AlphaFold2 multimer predictions for the top variants (NGS and AlphaFold compiled in Supplementary Fig. 13) and subcloned variants from passage four phage and collected luciferase binding assay for the top variant(s) cloned (Supplementary Fig. 14). Overall, we validated 79 new binders to 52 targets (Fig. 4b). These results further demonstrate the high correlation between endpoint titer and binder enrichment (discussion in Supplementary Note 1). For select targets that repeatedly produced false positives, we determined that expression needed tuning to improve de-enrichment of nonbinders and the optimized expression strains went extinct on the affibody library (Supplementary Table 7). We used 16 of our binders to investigate the specificity of our selected binders (Fig. 4c), identifying only one off-target interaction between GABARAP and our LC3B binder, which is not surprising given that both GABARAP and LC3B bind LIR domains37 (88% similarity at LIR binding site) and Ab-1(LC3B) has an LIR motif (SFEIL; F-type LIR). With this dataset of 288 pairwise binding measurements, we sought to evaluate the ability of AlphaFold3 (ref. 38) to identify binding versus nonbinding pairs; interface predicted template modeling (iPTM) values were not well correlated with binding (Extended Data Fig. 8).

Improving affinity and hit rate in PANCS-Binders

While the initial 55% hit rate and hundreds of nM dissociation constants (Kd) showcase the viability of PANCS-Binders, we wanted to assess whether we could improve the hit rate and identify higher affinity binders by simply using larger libraries in PANCS-Binders. We cloned 1010 variant libraries for both the affibody and affitin scaffolds using parallel transformations (Fig. 5a): a 100-fold improvement of our initial library size (Supplementary Table 8). We selected eight targets that did not give hits in our initial screens, including VHL, TRIM and PNCA, and four targets that previously generated hits, including KRAS G12D and RAF, and performed a large library PANCS-Binders screen (Fig. 5a) with six rounds of passaging over 72 h (see Methods for additional details and protocol differences). In addition to getting new hits for the targets that also initially gave hits with smaller libraries, three out of the eight previously failed targets now also yielded hits, as confirmed by the E. coli luciferase assay (38%; Fig. 5a and Supplementary Table 9). We analyzed these hits by NGS (Supplementary Fig. 18) and compared the new hits for KRAS G12D both using the E. coli luciferase assay and in vitro (Fig. 5b, binders for other targets shown in Supplementary Figs. 19 and 20): the affinity of the best binder obtained from this selection improved from 384 to 0.2 nM, representing a ~2,000× improvement in affinity. These results confirm that PANCS-Binders is capable of quickly mining 1010 variant libraries for novel binders, improving our hit rate (predicted from 55 to 72%) and identifying higher affinity binders, all within a 72-h selection.

a, Here, 1010 libraries were prepared using parallel transformations (Supplementary Table 8) that were pooled to initiate large library PANCS-Binders (Supplementary Table 9), which required starting at an initial volume of 500 ml and decreasing the volume of each passage slowly as the selection progressed (Supplementary Fig. 18 for NGS results). b, E. coli spRNAP complementation luciferase assay heatmap shown for successful selections, with slashes indicating selections that also gave hits in the 95 panel selections (Fig. 4). c, Luciferase assay results for large KRas G12D selection (Supplementary Fig. 19 for others) with in vitro affinity listed above each bar, comparing literature reference binder in gray, original binder from smaller scale selection in red and new binder in purple (Supplementary Fig. 20 for SPR). d, Affinity maturation of Mdm2-affibody hit by PACE. Passage four from the Mdm2 selection with the 108 affibody library (Fig. 3b) was used to seed PACE. PACE was initiated on a +AP selection strain with lower Mdm2 expression than the original PANCS. After 24 h, there was a 12-h mixing step with an even lower expression level strain for an additional 36 h (total of 60 h). Titers were monitored by activity-independent plaque assay, and variants were subcloned at 60 h (isolated variants shown here). LOD, limit of detection. e, Variants were tested in the luciferase binding assay alongside T-WDN and the nonbinding affibody (PDL1)48 as in Fig. 3b. Each condition has an n of 4 (a single measurement from four independent cultures), and error bars indicate mean ± s.d. Affinities measured by SPR (Supplementary Fig. 21) are shown above each luciferase bar graph. Note, all SPR fits are compiled in Supplementary Table 10.

One advantage of the PANCS-Binders technology is that the same selection strains and output phage can quickly be adapted to PACE by transforming the selection strain with a mutagenesis plasmid to allow mutations to accrue during a directed evolution campaign. To test this, we performed PACE-based directed evolution on the passage four phage from our initial Mdm2-affibody selection (Fig. 3b) using adaptations of our previous method24. First, we identified higher stringency positive APs with reduced propagation of passage four phage (as measured by activity dependent plaque assays). Then we used these two strains to perform PACE over the course of 60 h of evolution, after which the phage populations converged (six out of eight subclones sequenced) on an affibody variant Y-WCT with an additional A46T mutation and then an additional L51F mutation (in one-eighth with A46T, Fig. 5c). Assessment using the E. coli luciferase binding assays showed the evolved variants have improved affinity for their targets (Fig. 5d). We confirmed this in vitro: Kd = 8.4 nM for A46T and 26 nM for A46T/L51F (Fig. 5d and Supplementary Fig. 21) compared with 176 nM for the highest affinity Mdm2 binder identified from the initial PANCS (a >20× improvement). Critically, the mutations arising from the supplemental PACE are not in the initial randomization sites, nor are they predicted to make direct contacts with the target protein (Fig. 5c). This is not altogether surprising; the power of unbiased directed evolution via PACE for optimizing existing function through nonintuitive mutations is well-established. Finally, for all our binders with measured affinities (Supplementary Table 10), we demonstrate that the AlphaFold3 predicted iPTM values and the measured Kd have a low Peason’s correlation (−0.5; Supplementary Fig. 22).

Binders function in mammalian cells

Last, we sought to test whether the novel binders could be taken directly from PANCS-Binders into mammalian cells and bind their targets in a functionally relevant manner. We cloned the KRAS G12D binders Ab-N-VCD (Fig. 3b) and Ab-N-LHY (Fig. 5b) into a split nano-luciferase complementation assay39 and demonstrated robust binding in human embryonic kidney 293T (HEK293T) cells (Fig. 6a). Next, we sought to convert Ab-N-LHY into a KRAS degrader by fusing it to an LIR (LC3B interacting region) domain for targeted protein degradation through authophagy23 (Fig. 6b). We observed robust degradation of endogenous KRAS in U2OS as assessed by western blot in a binder-dependent manner (Fig. 6c,d and Supplementary Fig. 23). We then demonstrate that the high affinity Mdm2 binder (Ab-Y-WCT A46T) colocalizes with Mdm2 in the nucleus (Fig. 6e and Extended Data Fig. 9), confirming binding in mammalian cells. We then overexpressed AB-Y-WCT A46T and several other Mdm2 binders in U2OS cells to see whether the binders could inhibit the Mdm2-p53 interaction, by monitoring expression levels of Mdm2 and p21, which are both transcriptionally regulated by p53. We observed a strong induction of both targets on Mdm2 binder expression, which indicates robust inhibition of Mdm2 and activation of p53 (Fig. 6f–h and Supplementary Fig. 24). These results demonstrate that PANCS-Binders can produce binder variants with functional binding activity in mammalian cells.

a, Initial KRAS G12D (Fig. 3b) and high affinity KRAS G12D (Fig. 5b) binders were tested for binding in mammalian cells using a split nano-luciferase assay in HEK293T cells in comparison to a nonbinding target protein, UEV (Supplementary Table 3). Transfections were performed in triplicate (n = 3); error bars indicate mean ± s.d. RLU, relative luminescence units. b, Schematic showing LC3B recruiting element (LIR motif) fused to binders for targeted degradation by autophagy23. c, Representative western blot (WB) of endogenous KRAS degradation by Ab-N-LHY–LIR (Supplementary Fig. 23 for full blots and replicates). d, Quantification of replicate degradation results as shown in c (Supplementary Fig. 23, three transfected cultures for each condition, each experiment performed independently, n = 3) and error bars indicate mean ± s.d. For western blot quantification, a two-tailed t-test (P = 0.0336). e, Mdm2/Mdm2 binder colocalization: mCherry-tagged Mdm2 and GFP-tagged Mdm2 binder colocalize in the nucleus, while a control GFP does not (additional images of replicate transfections in Extended Data Fig. 9). f, Representative WB of Mdm2-p53 PPI inhibition; inhibition of this PPI activates p53 transcription resulting in increased expression of p21 and Mdm2 (Supplementary Fig. 24 for full blots and replicates). Quantification of replicate WBs for Mdm2-p53 PPI inhibition in U2OS cells. g, Mdm2 expression. h, p21 expression (Supplementary Fig. 24). Each sample on the blot is from an independent transfection/culture; three transfection experiments were repeated independently for each condition (n = 3), and error bars indicate mean ± s.d. For western blot quantification, statistical analyses were performed using one-way analysis of variance with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test binder versus control. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. For g, Y-WTT (P = 0.0033), Y-WCT (A46T) (P = 0.0006) and Y-WCT (A46T/L51F) (P = 0.0048) and for h, Y-WTT (P = 0.0276), Y-WCT (A46T) (P = 0.0028) and Y-WCT (A46T/L51F) (P = 0.0281).

Discussion

PANCS-Binders is a rapid, reproducible and reliable method for discovering protein binders. The entire process of cloning a target into the +AP/RNAPC expression plasmids, selection, assessment and secondary validation assays can routinely be performed in 2 weeks without the requirement for highly specialized expertise or equipment. PANCS-Binders can screen multiplexed libraries of 1010 phage-encoded variants across dozens of targets or 108 phage-encoded libraries across hundreds of targets in 2–3 days, yielding high affinity, selective binders with sufficient fidelity such that hits can be directly used in secondary assays, such as mammalian cell experiments. In our 96-well based high-throughput PANCS-Binders with 108 variant libraries, we achieved a 55% hit rate across a wide range of targets with a high correlation between endpoint titer and validated binding (79 out of 92), and this correlation is higher when target expression levels are modified to ensure robust de-enrichment (Supplementary Table 7). Within this group of targets, subsets of targets had very high success rates: targets with published synthetic binders (20 out of 27, 74%); bacterial, viral or other (nonhuman 15 out of 19, 79%); extracellular domains of surface targets (8 out of 14, 57%) and secreted proteins (10 out of 11, 91%). Overall, human targets had just a 51% hit rate (39 out of 76); however, this is reduced by two particular categories of targets: intrinsically disordered proteins (fully disordered 6 out of 16, 38%; partially disordered (5 out of 15, 33%)) and full-length single (four) or multipass (one) transmembrane proteins (zero out of five, 0%). Repeating a subset of failed human target selections with a 100-fold larger library produced hits for 38% of those initial failures (zero out of two for single-pass transmembrane, one in three for disordered targets and two in three for ordered targets), showcasing how simply scaling up library size can increase these initial hit rates. Additionally, either with large 1010+ libraries or through rapid affinity maturation via PACE, high affinity binders (<10 nM Kd) can be obtained quickly.

PANCS-Binders effectively links phage replication rates to binding activity of phage-encoded variants making PANCS essentially an ultra-high-throughput screen capable of sampling every pairwise interaction between a target protein and 1010+ variants of an interaction partner. We used this screen to perform selections of de novo binders from moderate (108) and large (1010) pools of highly diversified (14+ randomized positions) on roughly 100 antigens. Because antigens are expressed in the cytoplasm of E. coli, PANCS-Binders has several considerations and limitations for target choice; however, we believe the benefits of PANCS-Binders, namely fidelity and speed, offer unique benefits to this method over display-based methods or in silico methods for a wide range of target classes. As is true for any target removed from its native environment (that is, purified in vitro or overexpressed on a cell surface), there is no guarantee that the target will fold into the native structure with the native biochemical modifications. Because of this, binding of the antigen is not a guarantee of binding to the native target. Proper antigen selection is key for discovery of binders that function in the desired context. For targets where antigen folding is in question, the expression level (Extended Data Fig. 6) or the interaction of the antigen with a native binding partner (Fig. 2c) can be checked. For PANCS-Binders, the limitations for target selection fall into several categories: transmembrane proteins, disulfide rich proteins and proteins with particular posttranslational modifications (PTMs). First, because the split RNAP biosensor acts in the cytoplasm, this biosensor is not compatible with presentation of the target or binders in the cell membrane; however, for many membrane proteins, one can use either the intracellular or extracellular domain of single-pass transmembrane proteins in isolation or attempt to use techniques for solubilizing multipass transmembrane proteins40 or to display individual loops on soluble proteins. Second, because the E. coli cytoplasm is a reducing environment, overexpression of disulfide rich proteins for protein purification results in insoluble proteins often requires oxidants for proper refolding of the targets. While the lower expression of proteins in PANCS-Binders should allow for buried disulfides to form, the system can be modified to overexpress thiol oxidase and disulfide isomerase in the cytoplasm41 or the biosensor can be modified to target expression in the oxidative environment of the periplasm42,43. Third, many proteins exist in several proteoforms based on biochemical posttranslational modifications such as phosphorylation. Our system could be modified to incorporate several PTMs through noncanonical amino acids and amber suppression techniques44. However, we expect several modifications such as lipidation or many glycan modifications to be intractable with these techniques.

Despite these current limitations concerning the range of targets and the likelihood of antigens acting as adequate proxies for native targets, we believe that PANCS-Binders offers several critical advantages over display-based selections. First, because we use genetically encoded targets and PANCS-Binders can be multiplexed, many antigens for the same target protein can be tested in parallel without the need to purify each target; this is most relevant with choice of extracellular domains and of proteins with high degrees of disorder (many of which would be challenging to purify). Second, because we have the ability for simultaneous counterselection, we predict the use of modified antigens on the −AP for directing binding to parts of the target antigen that are not normally modified with PTMs. Third, because of the speed and fidelity of our system, the biophysical problem of identifying binders to our antigen can routinely be solved in days without the need for additional screening. Collectively, these three advantages mean that a researcher interested in binders to a single target could generate several +AP versions of the target antigen, several versions of the −AP modified antigen and perform multiplexed selections on dozens of +AP and −AP combinations to identify a range of binders to their target that all bind to the antigen in just two weeks. This dramatically reduces the time and effort required between target identification and testing of binders in the desired context to just 2 weeks (Fig. 1c) rather than the typical months for immunization or display-based techniques.

The speed of PANCS-Binders comes from its strong de-enrichment of weak and nonbinders and high enrichment of binders, which abrogates the need for secondary screening campaigns common in display-based selection techniques. We propose that two fundamental aspects of such techniques limit the relative enrichment of binding variants over nonbinding variants commonly achieved in display methods: threshold selection (bound or not bound) and activity-independent amplification. PANCS-Binders uses a split RNAP-based biosensor with a large dynamic range that links the degree of variant function to the degree of phage replication for that variant, both creating a gradient rather than threshold selection and removing the activity-independent amplification step. Notably, neither Alphafold2 multimer (Supplementary Fig. 15) nor AlphaFold3 (Extended Data Fig. 8 and Supplementary Fig. 22) could predict binding (false negatives) or nonbinding (false positives) from our screen, illustrating the enduring importance and value of real experimentation and limitations still inherent in computational modeling. Furthermore, the high-quality binding data generated through PANCS can be used in improving computational modeling and AI-based design techniques.

The ability to use high-diversity libraries in phage-assisted selections and evolutions is a powerful tool in the directed evolution arsenal and should expand the range of evolutions possible. PACE and PANCE have been applied to alter or tune the specificity of a variety of protein functions8,20,21,22,24,25,26,28,32,45; however, because mutations accumulate incrementally, these campaigns require a nearly continuous evolutionary pathway starting from low or non-functional initial variants. In a recent tour de force46, the evolution of a protein that binds a small molecule–protein complex, an elaborate pathway was needed to access the five mutations needed for minimal function and the eight mutations eventually reached for high function. This included repeated high mutagenesis drift periods, a three-position randomized library, stepping-stone states (a panel of 16 small molecules) and testing of a wide range of selection stringencies (PACE and PANCE across 26 different stringency selection plasmids). High-diversity libraries, such as those used here in PANCS-Binders, are prepared using in vitro diversification techniques capable of making tens of targeted mutations in the initial variant. PANCS is a powerful approach to jumpstart more difficult evolutionary campaigns by increasing the navigable distance between functional states.

PANCS-Binders generated hits for disordered protein targets and proteins that are challenging or impossible to purify, showcasing the potential of this screening and selection platform to discover binders for proteins that lack structural data or are incompatible with in vitro selection strategies. PANCS-Binders requires minimal optimization of selection conditions, as is commonly the case for two-hybrid selections; we applied to optimized expression levels surrounding the KRAS-RAF interaction to our entire 95-target panel. However, we do note that the target solubility can affect the target-RNAPC expression level, and in some cases, the target expression level must be adjusted to maintain robust de-enrichment of nonbinders (Supplementary Table 7); however, we solved this issue for several targets with a single modification to the +AP. Because a wide range of target expression levels are compatible with one or two +AP expression levels, with PANCS-Binders, one can ‘plug-and-play’ targets into the system without the need for extensive optimization for each target and/or antigen.

Methods

Cloning and bacterial strain handling

All plasmids and phage (Supplementary Table 1) were cloned by Gibson Assembly of PCR fragments generated using Q5 DNA polymerase (NEB). All primers (Supplementary Table 2) were ordered from IDT. Three E. coli strains were used in this work: DH10β (Thermo Fisher, cat. no. EC0113), BL21(DE3) (Thermo Fisher, cat. no. EC0114) and S1030 (Addgene 105063). For plasmids, Gibson Assembly mixtures were transformed into chemically competent DH10β E. coli and after a 1 h outgrowth in 2xYT media, were plated on antibiotic selective agar plates to isolate individual clones. For phage, Gibson Assembly mixtures were transformed into chemically competent S1030–1059 E. coli, and after a 2 h outgrowth, a plaque assay was performed to isolate individual phage clones. All plasmids and phage were confirmed by Sanger sequencing. All plasmid maps with annotations of key features are available in Supplementary Table 1. For constructing selection (+AP/−AP) and E. coli luciferase (2-22/N-lux/C-lux) strains, S1030 E. coli was made chemically competent and then single or double transformations were used (and then repeated as needed until all plasmids were incorporated). E. coli strains was grown on agar plates static at 37 °C or in solution at 37 °C with 200 rpm shaking with Luria-Bertani (LB) medium supplemented with the appropriate antibiotic unless otherwise indicated. Antibiotics were used at standard concentrations: kanamycin (40 μg ml−1), chloramphenicol (33 µg ml−1) and carbenicillin (100 µg ml−1).

Plaque assays

Activity-independent plaque assays can be used to determine the phage titer via plaque counting. Activity dependent plaque assays can be used to check for robust phage replication on a given strain. For activity-independent plaque assays, an S1030–1059 E. coli culture (1m059 plasmid encodes gIII expressed from the phage shock promoter to produce gIII after phage infection), is grown to stationary phase in LB with carbenicillin, subcultured at one part to ten in fresh LB with antibiotic to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.4–0.6 and then used as the selection strain in the plaque assay. Similarly, for activity dependent strains, S1030 with a +AP (and −AP) were grown similarly for use in the plaque assay. For the plaque assay, an initial dilution of the stock can be added based on the expected titer, but generally, 2 µl of a phage stock (or diluted stock) is added to 100 µl of subculture, mixed and then serially diluted (2 µl into 100 µl) to create four dilutions. Next 750 µl of 50 °C top agar (7 g l−1 agar, 25 g l−1 LB) was added to each dilution and then transferred in its entirety to one quadrant of a bottom agar plate (15 g l−1 agar, 15 g l−1 LB). After 10–16 h of incubation at 37 °C, plaques become visible and were counted in the quadrant with 10–200 PFU.

Phage amplification rates

To determine phage amplification rate, the titer of a phage stock is determined using an activity-independent plaque assay. Based on this titer, a diluted stock is made that should be 500 PFU μl−1 (the titer of this diluted stock is confirmed using an activity-independent plaque assay). The activity dependent strain (+AP or −AP) is grown to stationary phase in LB with carbenicillin and kanamycin, subcultured one part to ten in fresh LB with antibiotic to an OD600 of 0.4–0.6. Next, 2 µl, 1,000 PFU, are added to 1 ml of this subculture and then incubated at 37 °C with shaking for 12 h. The cells are then pelleted and the cell-free supernatant collected for use in an activity-independent plaque assay to determine the titer at the end of the amplification assay. The endpoint titer is divided by the starting titer (1,000 PFU ml−1) to determine the amplification rate.

PACS and PACE

General procedures for continuous flow experiments

PACS22 and PACE20 were performed as previously described. All tubing, chemostat bottles and lagoon flasks were bleached thoroughly, rinsed with dionized water and then autoclaved to ensure sterility. Then 10 l of carboys of Davis Rich media were prepared as described previously20. Inlet lines consist of short needles unable to reach the culture and outlet lines consist of long needles able to reach the culture. Each chemostat had an inlet line for fresh media, an inlet line with a sterile filter for airflow, an outlet line for waste and an outlet line for each lagoon. Each lagoon had an inlet line from the chemostat, an inlet line with a sterile filter for airflow and an outlet line for waste. For PACE lagoons, each lagoon also has an inlet line for arabinose. Each chemostat and lagoon has a magnetic stir bar. Colonies of the selection strain were used to inoculate 5 ml of culture in the relevant media (below) and grown to stationary phase. This culture was then used to inoculate a 200-ml chemostat (250-ml bottle). This culture was stirred in a 37 °C cabinet until an OD600 of ~0.5 and then fresh Davis Rich media was flowed into the chemostat at ~1 vol h−1. The chemostat was monitored for 4 h to ensure that the flow rate maintained a stable OD600 of ~0.5. Phage was then added to each lagoon, then culture was flowed into the lagoon to a volume of 20–25 ml and allowed to incubate for 1 h before beginning a flow of 1 vol h−1. Samples from the lagoons were collected from the waste lines at various timepoints.

PACE with libraries and with PANCS output

PACE was performed as describe previously20 in line with standard PACE protocols45. For PACE with RAF and IFNG with the affibody library (Supplementary Fig. 2), two selection strength strains were used for 36 h each with a 12-h mixing step (60 h total). +APs (ori, gIII/RNAPC RBS strength): p15 SD8/SD8 to pSC101 SD8/SD8 for RAF and from pSC101 SD8/SD8 to p15 SD8/sd5 for IFNG. In addition to the +AP, each strain had a ZBneg −AP (20-1) and MP6 (Supplementary Table 1). The initial selection strain supported activity dependent plaques of the affibody binders isolated from PANCS of the affibody library, confirming that binders capable of propagating on the initial selection strain exist in the library. One lagoon was used for each chemostat, initially seeded with 1010 PFU of library phage and arabinose began flowing during the 1 h of incubation of phage with culture in the lagoon before beginning flow at 1 vol h−1. Samples were collected before beginning the mixed strain phase (24 h) and after completion of the second strain (60 h), and titers were assessed by activity-independent plaque assay. For the PACE with Mdm2 (Fig. 5a) starting from the final passage of PANCS with the Affibody library (Fig. 3a), the same protocol was followed with the selection strengths of the +AP being pSC101 SD8/SD8 to p15 SD8/sd5 (both strains produced small activity dependent plaques using the passage four phage and large activity dependent plaques at the 60 h timepoint of PACE).

PACS with mock libraries

PACS was performed as describe previously22. The selection strain (S1030/31-69/20-6) was prepared by double transformation into chemically competent E. coli. Mock libraries were composed of 1010 PFU inactive phage (Affitin (SasA)) and varying amounts (zero (negative control), 10, 102, 103, 104 or 105 PFU) of active phage (RAF wild-type (WT)). In addition, a lagoon was seeded with only 103 active phage as a positive control. Each of these was done in duplicate lagoons and/or chemostats. Samples were taken at 12, 24 and 48 h and the titer was determined by activity-independent plaque assay (Supplementary Fig. 3).

PANCS

General protocol for PANCS

For each passage, a selection strain (+AP or −AP) is grown to stationary phase in LB with carbenicillin and kanamycin, subcultured 1/10 in fresh LB with carbenicillin and kanamycin to an OD600 of 0.4–0.6 before adding phage. For passage 1, stock phage are added to the subculture and incubated at 37 °C with shaking (200 rpm) for 12 h, then centrifuged to pellet the cells and collect the cell-free supernatant (referred to as passage 1 phage). For subsequent passages, some fraction of the cell-free supernatant from the previous passage is added to the subculture and incubated at 37 °C with shaking (200 rpm) for 12 h, then centrifuged to pellet the cells and collect the cell-free supernatant (referred to as passage no. phage). Titers of each passage or just the final passage were then determined using activity-independent plaque assays, or for the 96-target panel, using qPCR (below).

Details for specific PANCS

For PANCS development, a variety of culture volumes, transfer rates and number of passages were used. For the mock PANCS (Fig. 2e) and the six-target panel PANCS (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Table 4), we performed four-passage PANCS with 5 ml cultures, initially seeded with 1010 PFU for passage 1 and seeded with 250 µl of previous passage for passages 2–4 (5% transfer). For the 96-target panel PANCS (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Table 6), we performed four-passage PANCS with 1-ml cultures (2 ml deep 96-well plates), initially seeded with 2 × 109 PFU for passage 1 and seeded with 100 µl of previous passage for passages 2–4 (10% transfer). For additional passaging of this PANCS, we did 2% transfer for two passages (Supplementary Fig. 17). For the 1010 library PANCS (Fig. 5a), six-passage PANCS was performed using either a 2% (RAF, IFNG, KRAS G12D and HRAS) or 5% (PCNA, ALKBH5, PINK, PIK3CA, TRIM21, VHL, NIX and BAX) transfer rate between passages and passage 1 was seeded with 5 × 1010 PFU; however, unlike previous PANCS, the volume of each passage was changed as well: 500 ml for passage 1, 125 ml for passage 2, 25 ml for passage 3 and 5 ml for passages 4–6.

Split RNAP E. coli luciferase assays

We followed a slightly modified version of our previously reported assay20. For each target, a two-plasmid strain (S1030/2-22/C-lux) was made chemically competent and each binder and nonbinder N-Lux plasmid was transformed to make the three-plasmid luciferase strain. Colonies were picked for each binder and nonbinder for each strain to inoculate 1 ml of LB with kanamycin, chloramphenicol and carbenicillin and grown at 37 °C with shaking (200 rpm) for 12–16 h. Strains were then subcultured 7.5 µl into 143 µl of LB with kanamycin, chloramphenicol, carbenicillin and l-arabinose (2 mg ml−1 final concentration) on white side, clear bottom 96-well assay plates (Corning 3610) and incubated at 37 °C with shaking (200 rpm) for 3.5 h before reading the OD600 and luminescence signal on a BioTek Synergy Neo2 plate reader. Luminescence signal is first divided by the OD600 to normalize luminescence to cell growth. Then the luminescence or OD600 is normalized for all strains with the same C-Lux plasmid (target-RNAPC expression plasmid) are divided by the nonbinder signal (nonbinders set equal to 1). Due to differences in expression levels of each target and differences in how binding affects expression level of a target, we do not believe direct comparisons in fold change over nonbinder can be made across different targets and, therefore, we plot all binders for an RNAPC expression plasmid separately from other RNAPC expression plasmids.

NGS of PANCS hits

We used the Amplicon-EZ service provided by GENEWIZ (Azenta) for Illumina sequencing of each of our hits (GENEWIZ from Azenta, Amplicon-EZ) that provides 50,000+ paired-end reads per sample. We used primers to install Illumina partial adaptors (red or purple) and barcodes (blue) to PCR products extending from the linker to after the stop codon of our scaffold in phage (primed with green regions) (Supplementary Table 2). PCR was performed with Q5 DNAP polymerase (NEB) directly from phage (1 µl) in a 25 µl PCR reaction; the initial denaturation step was 10 min at 98 °C to release the single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) from the phage particle, a 63 °C annealing temperature Ta and a 40-s extension time were used with 30 cycles. PCR products are confirmed by gel (5 µl), and the remaining 20 µl of PCR product was pooled with other barcoded PCR products and column purified (Zymo DCC5). The Qubit double-stranded DNA High Sensitivity kit was used to determine an accurate concentration of the sample before dilution and submission for sequencing. For the NGS data in Fig. 3, Extended Data Figs. 1 and 4, and Supplementary Fig. 7, we used seven barcodes or sequencing samples yielding >15,000 reads per condition (library or PANCS passage). For the NGS data in Supplementary Figs. 13, 16 and 18, we used 24 barcodes or sequencing samples yielding >1,000 reads for nearly all PANCS samples (reads listed in tables for each library–target pairing in each figure). BB Merge was used to merge each paired-end read (https://jgi.doe.gov/data-and-tools/software-tools/bbtools/bb-tools-user-guide/bbmerge-guide/), then MATLAB was used to separate reads by barcode and translate them using modified scripts as described previously (our modified MATLAB scripts are provided in the Source Data file)49.

AlphaFold predictions

As a preliminary estimate of how our binders interact with their target, we used AlphaFold2 multimer collab (https://colab.research.google.com/github/sokrypton/ColabFold/blob/main/AlphaFold2.ipynb)50,51 for predicting the interaction between binder and target for the top four variants above 1% of reads (Supplementary Fig. 13). AlphaFold3 was released after this analysis, and we subsequently used AlphaFold3 (https://golgi.sandbox.google.com/)38 to predict binding interactions for each top variants from our six-target panel PANCS (Supplementary Fig. 8), our 1010 library PANCS (Supplementary Fig. 22) and for all of the binder–target pairs examined in Fig. 4c and Extended Data Fig. 8. We implore readers to use these predictions only for hypothesis generation rather than as data indicative of an actual interaction.

qPCR to estimate phage titers

qPCR was tested across several primers that prime to M13 phage genes for linear response of a phage serial dilution. Primers VC-525 and VC-526 were chosen (Supplementary Table 2). Power Up SYBR mix was used with the following PCR protocol: 10 min at 95 °C (to denature phage particle and release ssDNA); 40 cycles of 20 s at 95 °C, 20 s at 60 °C, and 20 s at 72 °C; then 10 s at 95 °C and 60 s at 65 °C. qPCR was run on a QuantStudio6Pro. Each run included a standard curve for which the titer was assessed using an activity-independent plaque assay.

Library construction

General protocol

Libraries were designed based on previously published randomizations29,52. Randomization was installed into a template phage using primers with degenerate codons (IDT; Supplementary Table 2). We optimized each step of this protocol to maximize the number of clones obtained. PCR conditions were optimized for each library to produce robust PCR product at 25 cycles and then tested for production at lower cycles to reduce amplification bias (18 or fewer cycles were used for each library reported here). PCR was then scaled up to produce 20–100 μg of PCR product. PCR products were concentrated using the Wizard Kit (Promega) and then digested using DpnI and NheI-HF (NEB) using a multidose cycle: for ~20–50 μg of PCR product in 300–400 μl, and then digested with DpnI and NheI, purified using a Zymo Gel Extraction kit and then ligated with T4 DNA Ligase (NEB). Ligated products were then electroporated into 1059 E. coli cells. The cells were then recovered in 50 ml of 37 °C SOC media and incubated for 2 h at 37 °C with shaking; samples were collected throughout this time for determining the titer by plaque assay. At 2 h, the cells were pelleted and the cell-free supernatant was collected. Then 1030–1059 (activity-independent replication strain) was grown overnight and then subcultured 1:10 with an OD600 of 0.6 at 37 °C with shaking (200 rpm). The phage (cell-free supernatant) was then amplified by adding the phage to this subculture for 8–10 h. At the conclusion of this outgrowth, cells were pelleted and the cell-free supernatant was sterile filtered to create the final library stock (titer determined by activity-independent plaque assay).

Affibody library

The affibody library (Extended Data Fig. 1) was cloned from the Affibody (PDL1) phage (Supplementary Table 1) using MS-783 and MS-618 (Supplementary Table 2) by Q5 DNAP (NEB) with a Ta of 68 °C. For generating the 108 size library, the E. coli strain used for the electroporation was SS320 (a highly electrocompetent strain that is capable of phage replication) rather than 10β. The 108 library size was generated with a single transformation of 3 μg of ligation product. For the 1010 library size, eight transformations of 10 μg of ligation product were performed (Supplementary Table 8).

Affitin library

The affitin library (Extended Data Fig. 5) was cloned from Affitin (SasA), a 1010 library or a version of the Affitin (SasA) phage with three stop codons inserted into a region randomized by the primers (Supplementary Table 1), or a 108 library, using MS-624 and MS-799 primers (Supplementary Table 2) by Q5 DNAP with GC enhancer with a Ta of 68 °C. Both the 108 and 1010 libraries were generated following the general protocol with a single 4-μg and eight 8-μg transformations, respectively (Supplementary Table 8).

Protein purification

General protocol for target proteins

Each target protein (KRAS G12D (1–169), RAF, IFNG and Mdm2) was cloned into a pET28 vector with a C-terminal 6xHis tag and transformed into BL21 E. coli (Supplementary Table 1). Cells were grown to an OD600 of 0.8 (37 °C with shaking), chilled on ice, induced with 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactoside (IPTG) and then incubated with shaking at 16 °C overnight. Cells were pelleted and resuspended in a lysis buffer (25 mM Tris (pH 7.8), 10% glycerol, 200 mM NaCl). Before lysing by sonication, cells were treated with phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. The soluble fraction of the lysate was incubated with Ni2+ resin, washed with lysis buffer containing 50 mM imidazole, then eluted in lysis buffer containing 250 mM imidazole and finally buffer exchanged into lysis buffer and concentrated.

General protocol for binder proteins

Each binder variant was cloned into a pET30 vector with an N-terminal 3xFlag and glutathione S-transferase (GST) tag and transformed into BL21 E. coli (Supplementary Table 1). Cells were grown to an OD600 of 0.8 (37 °C with shaking), chilled on ice, induced with 1 mM IPTG and then incubated with shaking at 16 °C overnight. Cells were pelleted and resuspended in a lysis buffer (25 mM Tris (pH 7.8), 10% glycerol, 100 mM NaCl). The soluble fraction of the lysate was incubated with GST resin, washed with lysis buffer, then eluted in lysis buffer containing 10 mM l-glutathione and finally buffer exchanged into lysis buffer and concentrated. Purified binders are shown in Supplementary Fig. 10.

SPR

SPR was performed on a Biacore 8000 using a nitrilotriacetic acid chip for immobilizing the His-tagged target proteins. Target concentrations were optimized to elicit a response of ~50–100 RU (180 s of 5 µl s−1) and then a range of binder concentrations were tested to identify concentrations that produced robust binding (90 s of 30 µl s−1). All SPR was conducted at 10 °C to maintain slow dissociation of the His-tagged immobilized protein. All dose responses were fit to a kinetic model for 1:1 binding using the Biacore evaluation software: all fits passed the quality checks in this software (Supplementary Table 10).

Split nano-luciferase assay

Here, 62.5 ng of the N terminus of nano-luciferase-binder fusion plasmid and 62.5 ng of the KRas(G12D) C terminus of nano-luciferase fusion plasmid were cotransfected into HEK293T (American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) cat. no. CRL-3216) cells using 500 ng of polyethylenimine in 96-well glass bottom plate (Cellvis, cat. no. P96-1-N). Transfection was performed in triplicate. After 36 h, the nano-luciferase activity was measured using Nano-Glo Live Cell Assay System (Promega, cat. no. N2011).

Endogenous KRAS degradation assay

Here, 1,000 ng of binder–LIR fusion plasmids were transfected into U2OS (ATCC HTB-96) cells by 0.3 µl of Lipofectamin 3000 in a 24-well plate. After 4 h, the medium was replaced. After 48 h, the cells were collected and subjected to western blot analysis with the appropriate antibodies (anti-KRAS (ProteinTech, cat. no. 12063-1-AP; 1:1,000), anti-tubulin-HRP (ProteinTech, cat. no. hrp-66031; 1:5,000), anti-mouse-HRP (Abcam, cat. no. ab6728, 1:5,000) and anti-rabbit-HRP (Abcam, cat. no. ab6721; 1:5,000)).

Mdm2 binder-Mdm2 colocalization assay

Here, 125 ng of the green fluorescent protein (GFP)-binder fusion plasmid and 125 ng of the mCherry-Mdm2 fusion plasmid were cotransfected into HEK293T cells using 0.075 µl of Xfect Transfection Reagent (Takara Bio, cat. no. 631317) in a 96-well glass bottom plate (Cellvis, cat. no. P96-1-N). After 4 h, the media was replaced. After 36 h, cells were imaged with a Leica fluorescence microscope.

Mdm2-p53 inhibition assay

Here, 1,000 ng of Mdm2 binder plasmids were transfected into U2OS cells by 0.3 µl of Xfect Transfection Reagent (Takara Bio, cat. no. 631317) in a 24-well plate. After 4 h, the media was replaced. After 48 h, the cells were collected and subjected to western blot analysis with the appropriate antibodies (anti-Mdm2 (Santa Cruz, sc-965; 1:1,000), anti-p21 (Santa Cruz, sc-6246; 1:1,000), anti-actin-HRP (ProteinTech, HRP-60008; 1:5,000), anti-mouse-HRP (Abcam, ab6728, 1:5,000) and anti-rabbit-HRP (Abcam, ab6721; 1:5,000)).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Links to electronic vector maps are included in Supplementary Information. All physical vectors will be made available on reasonable request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

-

Bandrowski, A., Pairish, M., Eckmann, P., Grethe, J. & Martone, M. E. The Antibody Registry: ten years of registering antibodies. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D358–D367 (2023).

-

Stanton, B. Z., Chory, E. J. & Crabtree, G. R. Chemically induced proximity in biology and medicine. Science 359, eaao5902 (2018).

-

Park, M. Surface display technology for biosensor applications: a review. Sensors 20, 2775 (2020).

-

Carter, P. J. & Lazar, G. A. Next generation antibody drugs: pursuit of the ‘high-hanging fruit’. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 17, 197–223 (2018).

-

Ayoubi, R. et al. Scaling of an antibody validation procedure enables quantification of antibody performance in major research applications. eLife 12, RP91645 (2023).

-

Laustsen, A. H., Greiff, V., Karatt-Vellatt, A., Muyldermans, S. & Jenkins, T. P. Animal immunization, in vitro display technologies, and machine learning for antibody discovery. Trends Biotechnol. 39, 1263–1273 (2021).

-

Sidhu, S. S., Lowman, H. B., Cunningham, B. C. & Wells, J. A. Phage display for selection of novel binding peptides. Methods Enzymol. 328, 333–363 (2000).

-

Xie, V. C., Styles, M. J. & Dickinson, B. C. Methods for the directed evolution of biomolecular interactions. Trends Biochem. Sci. 47, 403–416 (2022).

-

Wellner, A. et al. Rapid generation of potent antibodies by autonomous hypermutation in yeast. Nat. Chem. Biol. 17, 1057–1064 (2021).

-

Philpott, D. N. et al. Rapid on-cell selection of high-performance human antibodies. ACS Cent. Sci. 8, 102–109 (2022).

-

Lopez-Morales, J. et al. Protein engineering and high‐throughput screening by yeast surface display: survey of current methods. Small Sci. 3, 202300095 (2023).

-

Porebski, B. T. et al. Rapid discovery of high-affinity antibodies via massively parallel sequencing, ribosome display and affinity screening. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 8, 214–232 (2024).

-

McConnell, A., Batten, S. L. & Hackel, B. J. Determinants of developability and evolvability of synthetic miniproteins as ligand scaffolds. J. Mol. Biol. 435, 168339 (2023).

-

Kordon, S. P. et al. Isoform- and ligand-specific modulation of the adhesion GPCR ADGRL3/Latrophilin3 by a synthetic binder. Nat. Commun. 14, 635 (2023).

-

Baryshev, A. et al. Massively parallel measurement of protein-protein interactions by sequencing using MP3-seq. Nat. Chem. Biol. 20, 1514–1523 (2024).

-

Engelhart, E. et al. A dataset comprised of binding interactions for 104,972 antibodies against a SARS-CoV-2 peptide. Sci. Data 9, 653 (2022).

-

Younger, D., Berger, S., Baker, D. & Klavins, E. High-throughput characterization of protein-protein interactions by reprogramming yeast mating. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 12166–12171 (2017).

-

Cao, L. et al. Design of protein-binding proteins from the target structure alone. Nature 605, 551–560 (2022).

-

Bennett, N. R. et al. Atomically accurate de novo design of single-domain antibodies. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.03.14.585103 (2024).

-

Pu, J., Zinkus-Boltz, J. & Dickinson, B. C. Evolution of a split RNA polymerase as a versatile biosensor platform. Nat. Chem. Biol. 13, 432–438 (2017).

-

Esvelt, K. M., Carlson, J. C. & Liu, D. R. A system for the continuous directed evolution of biomolecules. Nature 472, 499–503 (2011).

-

Zinkus-Boltz, J., DeValk, C. & Dickinson, B. C. A phage-assisted continuous selection approach for deep mutational scanning of protein-protein interactions. ACS Chem. Biol. 14, 2757–2767 (2019).

-

He, H., Zhou, C. & Chen, X. ATNC: versatile nanobody chimeras for autophagic degradation of intracellular unligandable and undruggable proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 24785–24795 (2023).

-

Xie, V. C., Pu, J., Metzger, B. P., Thornton, J. W. & Dickinson, B. C. Contingency and chance erase necessity in the experimental evolution of ancestral proteins. eLife 10, e67336 (2021).

-

Miller, S. M. et al. Continuous evolution of SpCas9 variants compatible with non-G PAMs. Nat. Biotechnol. 38, 471–481 (2020).

-

Hubbard, B. P. et al. Continuous directed evolution of DNA-binding proteins to improve TALEN specificity. Nat. Methods 12, 939–942 (2015).

-

Packer, M. S., Rees, H. A. & Liu, D. R. Phage-assisted continuous evolution of proteases with altered substrate specificity. Nat. Commun. 8, 956 (2017).

-

Thuronyi, B. W. et al. Continuous evolution of base editors with expanded target compatibility and improved activity. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 1070–1079 (2019).

-

Woldring, D. R., Holec, P. V., Stern, L. A., Du, Y. & Hackel, B. J. A gradient of sitewise diversity promotes evolutionary fitness for binder discovery in a three-helix bundle protein scaffold. Biochemistry 56, 1656–1671 (2017).

-

Behar, G. et al. Whole-bacterium ribosome display selection for isolation of highly specific anti-Staphyloccocus aureus affitins for detection- and capture-based biomedical applications. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 116, 1844–1855 (2019).

-

Hu, J. H. et al. Evolved Cas9 variants with broad PAM compatibility and high DNA specificity. Nature 556, 57–63 (2018).

-

Dewey, J. A., Azizi, S. A., Lu, V. & Dickinson, B. C. A system for the evolution of protein–protein interaction inducers. ACS Synth. Biol. 10, 2096–2110 (2021).

-

Grimm, S., Salahshour, S. & Nygren, P. A. Monitored whole gene in vitro evolution of an anti-hRaf-1 affibody molecule towards increased binding affinity. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 534–542 (2012).

-

Spencer-Smith, R. et al. Inhibition of RAS function through targeting an allosteric regulatory site. Nat. Chem. Biol. 13, 62–68 (2017).

-

Karlsson, G. B. et al. Activation of p53 by scaffold-stabilised expression of Mdm2-binding peptides: visualisation of reporter gene induction at the single-cell level. Br. J. Cancer 91, 1488–1494 (2004).

-

Li, Y. et al. SYNBIP 2.0: epitopes mapping, sequence expansion and scaffolds discovery for synthetic binding protein innovation. Nucleic Acids Res. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkae893 (2024).

-

Birgisdottir, A. B., Lamark, T. & Johansen, T. The LIR motif—crucial for selective autophagy. J. Cell Sci. 126, 3237–3247 (2013).

-

Abramson, J. et al. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 630, 493–500 (2024).

-

Dixon, A. S. et al. NanoLuc complementation reporter optimized for accurate measurement of protein interactions in cells. ACS Chem. Biol. 11, 400–408 (2016).

-

Smorodina, E., Tao, F., Qing, R., Yang, S. & Zhang, S. Computational engineering of water-soluble human potassium ion channels through QTY transformation. Sci. Rep. 14, 28159 (2024).

-

Matos, C. F. et al. Efficient export of prefolded, disulfide-bonded recombinant proteins to the periplasm by the Tat pathway in Escherichia coli CyDisCo strains. Biotechnol. Prog. 30, 281–290 (2014).

-

Lee, B. & Wang, T. A modular scaffold for controlling transcriptional activation via homomeric protein–protein interactions. ACS Synth. Biol. 11, 3198–3206 (2022).

-

Morrison, M. S., Wang, T., Raguram, A., Hemez, C. & Liu, D. R. Author correction: Disulfide-compatible phage-assisted continuous evolution in the periplasmic space. Nat. Commun. 12, 6800 (2021).

-

Allen, M. C., Karplus, P. A., Mehl, R. A. & Cooley, R. B. Genetic encoding of phosphorylated amino acids into proteins. Chem. Rev. 124, 6592–6642 (2024).

-

Miller, S. M., Wang, T. & Liu, D. R. Phage-assisted continuous and non-continuous evolution. Nat. Protoc. 15, 4101–4127 (2020).

-

Mercer, J. A. M. et al. Continuous evolution of compact protein degradation tags regulated by selective molecular glues. Science 383, eadk4422 (2024).

-

Block, C., Janknecht, R., Herrmann, C., Nassar, N. & Wittinghofer, A. Quantitative structure-activity analysis correlating Ras/Raf interaction in vitro to Raf activation in vivo. Nat. Struct. Biol. 3, 244–251 (1996).

-

Jing, L. et al. Screening and production of an affibody inhibiting the interaction of the PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint. Protein Expr. Purif. 166, 105520 (2020).

-

Rentero Rebollo, I., Sabisz, M., Baeriswyl, V. & Heinis, C. Identification of target-binding peptide motifs by high-throughput sequencing of phage-selected peptides. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, e169 (2014).

-

Mirdita, M. et al. ColabFold: making protein folding accessible to all. Nat. Methods 19, 679–682 (2022).

-

Evans, R. et al. Protein complex prediction with AlphaFold-Multimer. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.10.04.463034 (2022).

-

Mouratou, B. et al. Remodeling a DNA-binding protein as a specific in vivo inhibitor of bacterial secretin PulD. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 17983–17988 (2007).

-

Koide, A., Wojcik, J., Gilbreth, R. N., Hoey, R. J. & Koide, S. Teaching an old scaffold new tricks: monobodies constructed using alternative surfaces of the FN3 scaffold. J. Mol. Biol. 415, 393–405 (2012).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (grant nos. GM119840 to B.C.D. and F32GM147968 to M.J.S.) and then National Cancer Institute (grant no. P30CA014599) of the National Institutes of Health, and by the Camille and Henry Dreyfus Foundation Teacher Scholar Award (B.C.D.). We thank S. Ahmadiantehrani for assistance with preparing this paper.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

B.C.D. is an inventor on the patent describing the split RNAP biosensors. The University of Chicago has filed a provisional patent on the PANCS-Binders technology with M.J.S. and B.C.D. listed as inventors. B.C.D. is a founder and holds equity in Tornado Bio, Inc. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Methods thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Allison Doerr, in collaboration with the Nature Methods team.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Affibody library construction.

a) The affibody structure with constant residues in blue and randomized residues in red29. b) The template phage used when cloning the library and the position and possible codons in the library variants. c) Monitoring of total phage after transformation (n = 1). The early timepoints (highlighted in green) are a lower-bound on the number of variants in the library (5*107) and the 2 h timepoint is the upper-bound (2*109) as the phage were separated from the transformed cells at this timepoint. We refer to this as a 108-variant library.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Selections with continuous flow: PACE and PACS.