Despite increasing evidence linking alcohol consumption to cancer, little is known about the biological mechanisms behind the association. Now, researchers at the University of Miami report that inhibiting a cellular molecule called CREB might thwart pancreatic tumor development in response to alcohol. The team published its study “CREB drives acinar cells to ductal reprogramming and promotes pancreatic cancer progression” in mouse models of alcoholic pancreatitis.

“Our model serves as an important platform for understanding how chronic inflammation related to alcohol consumption accelerates the development of pancreatic cancer,” said Siddharth Mehra, PhD, a scientist at the Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of Miami, and first author on the study.

Chronic, high alcohol use damages acinar cells in the pancreas—specialized epithelial cells that synthesize, store, and secrete digestive enzymes. The damage in turn causes the cells’ enzymes to increase inflammation in the tissue, exacerbating damage to the pancreas.

Over time, precancerous lesions can develop, increasing the risk for full-blown pancreatic cancer, one of the deadliest types of tumors. Previous studies have implicated CREB, a DNA-binding protein that regulates gene activity, and associated molecules in helping to mediate this process.

Progression to cancer also generally requires other cellular events, such as a mutation in a pro-cancerous gene called Ras, which commonly occurs in pancreatic tumors.

Recapitulated alcohol-induced inflammation

In the new study, the researchers developed a model that recapitulated alcohol-induced inflammation, the development of pre-cancerous lesions and progression to cancer. The model contained Ras mutations in acinar cells, and it also had an intact CREB gene that could be experimentally knocked out in these cells.

“Chronic alcoholism often leads to pancreatitis, which exacerbates pancreatic damage through acinar cell injury, fibrotic inflammation and activates AKT/mTOR/cyclic adenosine monophosphate response element binding protein 1 (CREB) signaling axis. However, the molecular interplay between oncogenic KrasG12D/+(Kras*) and CREB in promoting pancreatic cancer progression under chronic inflammation remains poorly understood,” write the investigators.

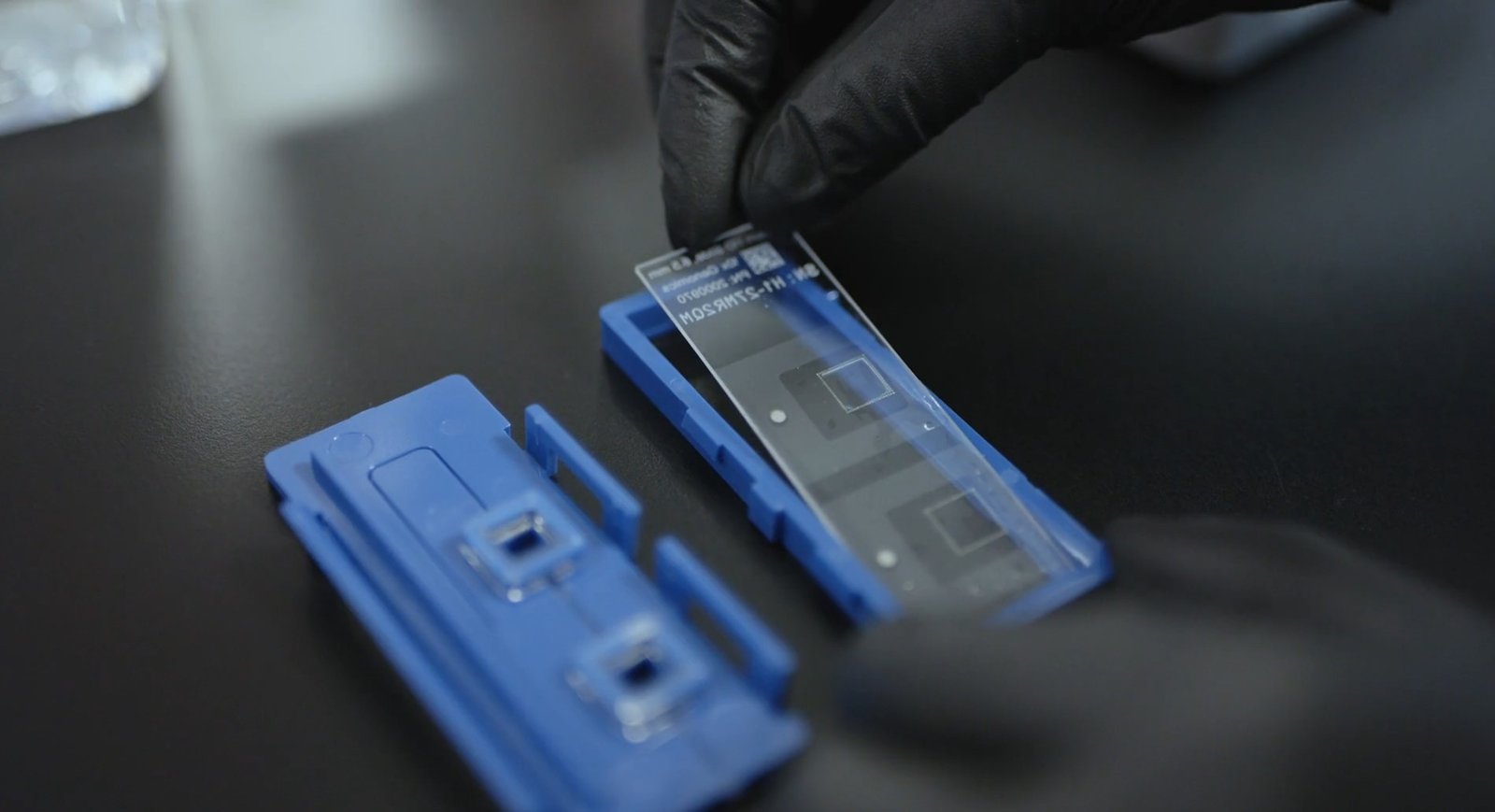

“Experimental alcoholic chronic pancreatitis (ACP) induction was established in multiple mouse models, with euthanasia during the recovery stage to evaluate tumor latency. CREB was selectively deleted (Crebfl/fl) in Ptf1aCreERTM/+;LSL-KrasG12D/+(KC) genetic mouse models (KCC-/-). Pancreata from Ptf1aCreERTM/+, KC, and KCC-/- mice were analyzed using histological profiling, western blotting, phosphokinase array, and quantitative PCR.

“Single-cell RNA sequencing was performed in ACP-induced KC mice. Lineage tracing analysis in YFP reporter mice and acinar cell explant cultures analysis was also conducted.

“ACP induction in KC mice significantly impaired pancreas’ repair mechanism. Acinar cell-derived ductal lesions demonstrated sustained CREB hyperactivation in acinar-to-ductal metaplasia (ADM)/pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN) lesions associated with pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer. Persistent CREB activity reprogrammed acinar cells, and increased profibrotic inflammation. Notably, acinar specific Creb deletion in ACP induced models suppressed high grade PanIN development, restrained tumor progression, and improved acinar cell function.

“Our findings demonstrate that CREB and Kras* promote irreversible ADM, accelerating pancreatic cancer progression with ACP. Targeting CREB may present a promising strategy to mitigate inflammation-driven pancreatic tumorigenesis.”

Development of symptoms similar to alcohol-induced pancreatitis

The researchers found that exposure to alcohol and a pro-inflammatory molecule caused the development of symptoms similar to alcohol-induced pancreatitis, an inflammatory condition. Inflammation in turn prompted the development of precancerous lesions and, later, cancer. Consistent with previous studies, CREB was highly activated throughout this transition process.

The researchers next knocked out CREB and found that they could quell the development of precancerous and cancerous lesions, even in the continued presence of alcohol. Knocking out CREB also relieved damage to acinar cells.

The findings hint that inhibitors of CREB might have therapeutic potential in people who have high alcohol use. Such inhibitors could potentially relieve damage to the pancreas and thwart tumor development, said the researchers.

“We found that CREB is not just a mediator of inflammation; it is a molecular orchestrator that permanently converts acinar cells into precancerous cells, which ultimately progress to high-grade neoplasia,” said senior author Nagaraj Nagathihalli, PhD, associate professor of surgery and assistant director of the Sylvester Pancreatic Cancer Research Institute at the University of Miami.

Future studies should help provide additional information about how alcohol use promotes pancreatic cancer development. Questions include whether similar events occur in human cells and tissues and what other molecules and cells play a role in the process. CREB activation may also be involved in other alcohol-linked cancers, speculates Nagathihalli who, along with colleagues, is also leveraging the model to investigate the potential of CREB inhibitors, which are under development as potential cancer therapeutics.

“We believe this study lays the groundwork for future translational efforts targeting CREB as a therapeutic vulnerability in inflammation-associated pancreatic cancer,” said study co-author Nipun Merchant, MD, Sylvester associate director of translational science and chief of surgical oncology.

The U.S. surgeon general recently declared alcohol the third leading preventable cause of cancer.

The post Breaking the Link Between Alcohol Use and Pancreatic Cancer appeared first on GEN – Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology News.