Introduction

The emergence of base editing tools has greatly expanded the application scope of the CRISPR/Cas system, and has enabled genome editing with base-level precision1. Current base editors (BEs) predominantly incorporate deaminase2,3 or glycosylase4 activities with a given CRISPR/Cas platform. Due to the single-stranded DNA substrate preference of the deaminase or glycosylase enzyme activities, along with the R-loop structure formed by the Cas complex during DNA targeting, most BEs act via directly modifying bases on the non-target strand (NTS) (except for the dsDNA-targeting DddA deaminases)5. Commonly used deaminase-based editors, such as BE4max6 and ABE8e7, respectively, facilitate C-to-T (CBE) and A-to-G (ABE) editing on the NTS. On the other hand, the glycosylase BEs, including gGBE8, AYBE9,10, CGBE11,12, and gTBE11,13, generate apurinic/apyrimydinic (AP) sites by cleaving target base on the NTS and drive subsequent DNA repair to install base transition or transversion (including C-to-G, T-to-S, A-to-Y, and G-to-Y). Although most BEs are developed via adopting the well-studied CRISPR-Cas9 platform, the large size of Cas9 has limited the packaging and delivery of BE for advanced applications. Furthermore, all existing CRISPR-dependent BEs feature certain NTS-editing windows as only a segment of the guide RNA target site. Such an editing window-related constraint limits the genome-wide coverage of the BEs.

In this study, we initially implement computational modelling and saturation mutagenesis of a small Cas protein (Un1Cas12f1)14,15, to develop a high-activity variant (enUn1Cas12f1) that presents strong in vivo activity. Subsequent survey of enUn1Cas12f1-derived BEs not only confirms their superior canonical base editing activities, but also reveals an unexpected activity by an evoCDA1-adapted CBE to also target the cytosines situated on the target strand (TS) of the on-target loci. Conceivably, such an unexpected activity can be harnessed to establish BE tools with substantially expanded genomic coverage. To seek possible variant forms of enUn1Cas12f1 that may selectively cleave the NTS (as an NTS nickase) to potentiate the eventual installation of TS edits, we perform alanine-scanning mutagenesis in domains corresponding to the nuclease lobe structure. This led to the identification of an additional mutant Cas12f BE variant with much improved TS-editing BE activities (TSminiCBE). Further analyses validate that such improvement is attributed to the property of TSminiCBE to serve as an NTS nickase. We also provide evidence that fusion of TSminiCBE with the DNA-binding HMG-D protein further enhances its editing efficiency. Together, our work establishes a toolkit of high-activity, Cas12f-based BEs that can be adapted to primarily target either the NTS or TS for diverse advanced applications.

Results

Un1Cas12f1 protein engineering for improvement of activities

The recently characterized CRISPR/Cas12f family has presented strong potential as genome editing tools conducive to efficient delivery, due to the small sizes of Cas12f proteins14,15. To circumvent the low efficiencies of the prototype Cas12f/guide RNA systems in mammalian cells16,17, previous efforts have focused on optimizing the best characterized member of the family, i.e., Un1Cas12f114,15. These works showed that engineering of the guide RNA scaffold18, or of the Cas12f protein moiety16,19 could improve the editing efficiencies of Un1Cas12f1. Despite such enhancement efforts, the editing efficiency of Un1Cas12f1 still lagged behind that of SpCas9. Besides the nuclease-dependent genome editing by Cas12f, base editing applications represent a particularly anticipated direction for Cas12f1-dependent editors20. Since numerous recent studies have demonstrated the power of adopting activity-improved Cas proteins to refine BE activities21,22, we reasoned that establishing further enhanced Un1Cas12f1 variants would represent a key step toward the development of advanced BEs applicable for in vivo contexts.

We sought an independent strategy to identify enhancement mutants of Un1Cas12f1. In the CRISPR/Cas system, the formation of the Cas proteins, guide RNA (gRNA), and targeted DNA complex drives the targeting activity23. In type II and V CRISPR systems featuring Cas924 or Cas12s25,26,27, the stability of the Cas/guide RNA RNP/target DNA plays a critical role in determining the DNA cleavage efficiency. Therefore, we sought to enhance the stability of the overall Un1Cas12f1-nucleic acids complex through more unbiased screening efforts. Based on previous refinements of Un1Cas12f1’s guide RNA architecture, we adopted the established gRNA4.1 scaffold18 throughout this study.

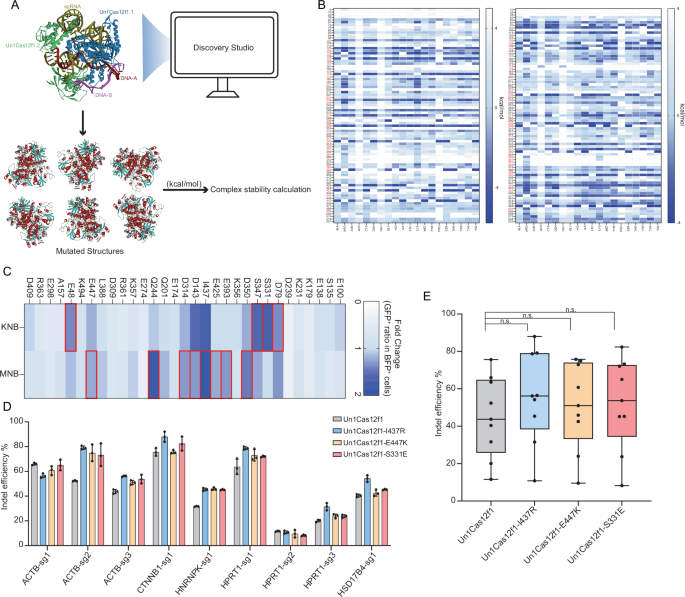

To properly select beneficial amino acid mutations, we combined computational predictions with a saturation mutagenesis strategy (Fig. 1A and Supplementary Fig. 1A). Using the resolved structure of the Un1Cas12f1-nucleic acid complex (PDB:7l49), we employed Discovery Studio 2019 software to simulate the impact of saturation mutations across all 529 amino acids on complex stability (Fig. 1A). Based on the prediction results (Fig. 1B and Supplementary Fig. 1B), we selected 31 amino acid positions for saturation mutagenesis to identify beneficial mutations. For 31 amino acid residues, we adopted two degenerate codons (KNB and MNB) and correspondingly constructed 62 mini-libraries. To streamline the identification of effective mutations, we constructed a cleavage-responsive reporter system to assess the editing rates following saturation mutagenesis of the selected positions (Supplementary Fig. 2A). The 62 mini-libraries were transfected into cells along with reporter plasmids to assess the GFP recovery ratio by fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) (Supplementary Fig. 2B). After identifying 17 most effective positions/degenerate codon groups (Fig. 1c), we further constructed individual mutants corresponding to all amino acid types within each candidate group. The editing efficiencies of these mutants were further screened using the reporter system. Subsequently, we identified over 40 mutation types with improved DNA cleavage performance in the reporter system (Supplementary Fig. 3). The effects by three of such mutations (I437R, E447K, and S331E) were subjected to further analyses. The plasmid containing each point mutant of Un1Cas12f1, along with individual gRNAs targeting a series of genomic loci, was transfected into HEK293T cells. Forty-eight hours post-transfection, mCherry+ cells (indicating successful guide RNA construct transfection) were sorted by FACS. Targeted NGS analyses were performed. Compared to the editing rates of the wild-type Un1Cas12f1 (44.98 ± 21.54%), all three mutants demonstrated improved DNA cleavage efficiency (respectively at 55.58 ± 24.57%, 50.79 ± 23.20%, and 52.07 ± 24.37%) (Fig. 1d, e).

A Overall workflow for bioinformatic prediction of the impact of amino acid mutations on the stability of Un1Cas12f1 protein-nucleic acid complexes, based on the PDB structure 7l49. The lower part of the panel illustrates six examples of mutant structural models (with α-helixes in dark red and β-sheets in blue). Energy differences for various mutated structures, each carrying a distinct single-point amino acid mutation, were calculated in kcal/mol. B The heatmap displays the kcal/mol changes resulting from mutations at various sites to all 20 amino acids. Lower values (represented by deeper blue) indicate increased stability post-mutation. Left and right panels correspond to simulations with each of the Un1Cas12f1 monomer within the dimer structure. The candidate positions for further analyses are marked in red. C The cleavage-responsive EGFP reporter was targeted by various Un1Cas12f1 mutant mini libraries corresponding to indicated positions and degenerative codon groups. The reporter activity was measured by flow cytometry. The results are shown as a heat map. The target sequence used is ATTTCCAAGTCAACCTTATG. Fold changes were calculated relative to the wild type, which was set as 1. The candidate position/degenerative codon groups for further screening are marked with red boxes. The FACS gating strategy is depicted in Supplementary Fig. 2B. Data were obtained from biological replicates (n = 3). Mean values are presented. D The indel-inducing activities at various genomic loci (nine) by three Un1Cas12f1 point mutants vs. the WT. Data were obtained from biological replicates (n = 3). Mean values (±SD) are presented. E.Box-and-whisker plot corresponding to data in (D). Each data point reflects the average from three biological replicates. In the plot, the center line shows the median of all data points (n = 9 sites) in a group, the box limits correspond to the upper the lower quartiles, and the whiskers indicate the minimum and maximum values within 1.5 times the interquartile range from the lower and upper quartiles. “n.s.”: (p > 0.05, two-sided, unpaired Student’s t test).Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Although such validation on the representative hits demonstrated the effectiveness of our screen, the results suggested that single-point mutations were typically associated with only modest improvement effects. To further enhance Un1Cas12f1 activity, we selected eight single-point mutations (including D143R, Q244R, E393R, S331E, S347E, E425R, I437R, and E447K), and used Discovery Studio 2019 software to simulate the impact of various combinations (double or triple substitution) of these mutations on the stability of the protein-nucleic acids complex. Based on the prediction results, we next selected 14 double- and triple-site mutants with the highest stability scores and proceeded to test their editing performance in human cells (Fig. 2A). As described earlier (Supplementary Fig. 2A), the mutants were transfected into HEK293T cells along with the reporter system to assess DNA cleavage performance. The GFP recovery ratio indicated that all combinatorial-substitution mutants showed significantly enhanced editing efficiency over the WT Un1Cas12f1 (Fig. 2B). Building on the best-performing combination (D143R + Q244R + E393R, DQE3R), we further introduced additional point mutations to construct a series of quadruple, quintuple, and sextuple combinatorial-substitution mutants and evaluated their editing efficiency using the reporter system (Fig. 2C). Ultimately, we established three highly efficient variants: Un1Cas12f1v1.1 (DQE3R-S331E), Un1Cas12f1v1.2 (DQE3R-I437R-E447K), and Un1Cas12f1v1.3 (DQE3R-S331E-I437R-E447K). All three mutants demonstrated higher editing activity at various endogenous loci in both HEK293T cells (60.57 ± 19.70%, 61.12 ± 20.03%, and 61.79 ± 20.50%) and HeLa cells (46.60 ± 21.58%, 45.56 ± 21.99%, and 50.18 ± 21.82%), compared to wild-type Un1Cas12f1 (29.51 ± 21.74% in HEK293T cells and 25.18 ± 22.12% in HeLa cells) (Fig. 2D, E). Further analysis revealed that Un1Cas12f1v1.1, Un1Cas121v1.2, and Un1Cas12f1v1.3 exhibited overall similar indel patterns as the wild-type Un1Cas12f1 (Fig. 2F), except that the three variants presented a greater tendency to cause deletions of 10 ~ 15 bp in both cell lines.

A Stability predictions for Un1Cas12f1 harboring double or triple mutations, following the same process shown in Fig. 1A. Red circles highlight combinations with the lowest kcal/mol, which were selected for further validation. B The cleavage-responsive EGFP reporter was targeted by fourteen selected combinatorial mutants. The green boxes indicate various mutated sites. Mean fold changes were calculated from biological replicates (n = 3), with the WT level set as 1. C Assessment of quadruple, quintuple, and sextuple variants for reporter-targeting activities as done in (B). Red pentagrams highlight the three variants designated as Un1Cas12f1V1.1, 1.2, and 1.3. Mean fold changes were calculated from three biological replicates. D Comparison of indel-inducing activities at various genomic loci by Un1Cas12f1V1.1, 1.2, and 1.3 and the WT control in HEK293T and HeLa cells. Data were obtained from biological replicates (n = 3, mean ± SD). E Box plots summarize the results in (D). Each point represents the average editing level from three biological replicates. In the plot, the center line shows the median of all data points (n = 11 sites) in a group, the box limits correspond to the upper the lower quartiles, and the whiskers indicate the minimum and maximum values within 1.5 times the interquartile range from the lower and upper quartiles. Statistical significance is denoted by * for p < 0.05, ** for p < 0.01, and “n.s.” for non-significant (two-sided, unpaired Student’s t test). The p values between V1.1/1.2/1.3 and WT are 0.002202, 0.002026, 0.001864 (HEK293T), and 0.032457, 0.042518, 0.014776 (HeLa). F Size distributions of deletions (ranging from 1 to 40 bp) caused by the three variants and WT Un1Cas12f1 (in D) are presented, given the preferential induction of deletions than insertions. The patterns in HEK293T (left) and HeLa cells (right) are shown. Measurements from three biological replicates corresponding to each size and target site were first averaged. The deletion size-segregated mean values across the 11 sites are used for plotting. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Previous studies have shown that enhancing DNA binding could improve the rate of CRISPR transcriptional activation tool based on dead Un1Cas12f1, as seen with the variants named CasMINI16 and miniCRa19. We investigated whether these previously reported DNA-binding mutations could be introduced into our well-performing variants Un1Cas12f1v1.1 and Un1Cas12f1v1.3 to achieve better performance. We selected two independent enhancement mutations from Un1Cas12f1-derived miniCRa (T147R and T203R, besides the common D143R substitution19), and introduced these double substitutions into Un1Cas12f1v1.1 and Un1Cas12Ff1v1.3 to construct Un1Cas12f1v2.1 and Un1Cas12f1v2.2, respectively. In the reporter test, both Un1Cas12f1v2.1 and Un1Cas12f1v2.2 outperformed the miniCRa-type variant in HEK293T cells (Supplementary Fig. 4A). A consistent pattern was achieved at multiple genomic loci (61.50 ± 11.21% for v2.1, 63.82 ± 13.44% for v2.2, vs 36.01 ± 22.02% for the miniCRa variant) (Supplementary Fig. 4B, C). Interestingly, compared to Un1Cas12f1v1.2 described in the previous section, consolidation of the present and previous collections of enhancement mutations (v2.1 and v2.2) did not present additive benefits in editing efficiencies (Supplementary Fig. 4D, E), suggesting that an activity plateau might have been achieved with v1.2 and with v2.1/2.2 in these cells. Further analysis of the indel patterns revealed no significant differences among these Un1Cas12f1 variants (Supplementary Fig. 4F). For the subsequent experiments, we selected Un1Cas12f1v2.2 as an optimal variant (incorporating enhancement mutations from two studies) and renamed it to enUn1Cas12f1. Importantly, the total expression levels of the enUn1Cas12f1 and Un1Cas12f1 were not considerably different (Supplementary Fig. 4G), which confirmed that the enhancement effects were attributed to improved Un1Cas12f1 activity. To more comprehensively assess the performances by enUn1Cas12f1, we also compared it with the well-known CasMINI variant16. The results showed that enUn1Cas12f1 also outperformed CasMINI (Supplementary Fig. 4H).

Previous studies have shown that sgRNA-guided nuclease-inactive SpCas9 or AsCas12a could be used to block transcription elongation headed toward the PAM-proximal side28,29. It is conceivable that the extent of such road-blocking activity against gene transcription could reflect the overall stability of a dCas protein/sgRNA/target complex. Therefore, we designed an experiment to measure the inhibitory activities of the nuclease-inactive Un1Cas12f1 and the enUn1Cas12f1 variants on an EGFP reporter. To this end, we introduced D326A/D510A nuclease-inactivating mutations to Un1Cas12f1 and enUn1Cas12f1. The dCas9 would be used as a positive control. For comparisons between dCas12f and dCas9, we considered overlapping target sites on opposite strands, with their polarities conducive to transcriptional road blocking (the complex’s PAM-proximal side facing direction of transcription28,29). In addition, two parallel sets of target sites (1 and 2) in EGFP were selected (Supplementary Fig. 5A). Cells were co-transfected with the EGFP reporter, various dCas/sgRNAs, along with a CMV-BFP plasmid as a control to normalize transfection efficiency. Fluorescence intensity was measured 48 h post-transfection using FACS to quantify the repression effect. The results showed that d-enUn1Cas12f1 significantly outperformed the prototype dUn1Cas12f1 in reducing EGFP expression and even presented higher activities than the dCas9 positive control (Supplementary Fig. 5B). These results support that enUn1Cas12f1/sgRNA/target complex is more stable than the counterpart based on Un1Cas12f1.

Further performance validation of enUn1Cas12f1 in human cells

SpCas9 is the most widely used and efficient genome editing tool, while enAsCas12f currently ranks as the most efficient within the Cas12f family26. To evaluate the relative performance of enUn1Cas12f1 compared to these two existing platforms, we conducted editing efficiency tests at multiple genomic loci in two human cell lines. Both enAsCas12f and enUn1Cas12f1 can recognize the TTTR PAM, allowing for a rapid side-by-side comparison at targets proceeded by this PAM. Given that SpCas9 recognizes the NGG PAM with a different orientation, we selected the TTTR-N(20)-NGG sequence pattern to enable efficiency comparison between enUn1Cas12f1 and SpCas9. All transfection conditions were standardized, including the same amounts of the editors and their corresponding gRNAs, as well as a 48-hour editing period. The top 15% of cells by fluorescence intensity were selected via flow cytometry, and the DNA samples were subjected to NGS. Un1Cas12f1v2.1 was also included in the study for further comparisons.

In both HEK293T and HeLa cells, enAsCas12f displayed similar editing efficiencies (39.60 ± 16.43% in HEK293T cells and 21.54 ± 14.95% in HeLa cells) as shown in the previous report (41.4 ± 16.6% in HEK293T cells and ~20% in HeLa cells)26. Importantly, enUn1Cas12f1 generally demonstrated higher editing efficiencies (63.18 ± 11.56% in HEK293T cells and 43.17 ± 13.38 in HeLa cells) than enAsCas12f (Supplementary Fig. 6A–D). In a similar trend, Un1Cas12f1v2.1 also displayed higher efficiency (62.32 ± 12.41% in HEK293T cells and 40.25 ± 21.45% in HeLa cells) compared to enAsCas12f. However, in HeLa cells, the Un1Cas12f1v2.1-dependent indel levels showed large variations, unlike the more consistent performances by enUn1Cas12f1. Further analysis revealed that enUn1Cas12f1 and Un1Cas12f1v2.1 tended to produce deletions (mostly 10–20 bp) that were larger than those by enAsCas12f (Supplementary Fig. 6E).

Additionally, while the editing efficiency of Un1Cas12f1v2.1 (58.34 ± 17.03% in HEK293T cells and 25.25 ± 15.39% in HeLa cells) is slightly lower than that of SpCas9 (69.32 ± 16.39% in HEK293T cells and 45.08 ± 18.55% in HeLa cells), enUn1Cas12f1 (60.60 ± 14.31% in HEK293T cells and 37.46 ± 15.60% in HeLa cells) shows no significant difference in editing efficiency compared to SpCas9 in both cell lines (Supplementary Fig. 7A–D). The two nucleases presented their typical, but highly distinct editing product patterns (Supplementary Fig. 7E), suggesting the alternative suitability of these tools for different needs. As SpCas9 had shown potent activities across diverse sequence contexts, we subjected enUn1Cas12f1 to tests on all possible targets within particular genes. To this end, we designed all possible gRNAs based on the TTTR PAM sequence for all exons of the CD3G and RIT1 genes. We then assessed the editing efficiencies using these gRNAs in HEK293T and HeLa cells. According to NGS results, except for gRNAs containing a continuous stretch of four T, which most probably impeded transcription by the U6 promoter and resulted in lower editing efficiency, the remaining sites displayed high editing efficiency in both cell lines (Supplementary Fig. 8).

The most common application of Cas9 and Cas12 proteins in mammalian cells is to generate gene-targeted indels for frameshift-dependent knockouts30,31. However, when targeting non-coding functional regions, achieving the desired outcome of inactivation requires introducing two gRNAs simultaneously to delete the large intervening fragment32,33. We therefore designed experiments to compare the efficiencies of enUn1Cas12f1, enAsCas12f, and SpCas9 to drive different-sized deletions in HEK293T cells. To drive deletion at a genomic region, one sgRNA targeting the upstream position (P1) was combined, respectively, with one of four other sgRNAs that corresponded to different downstream positions (P2-P5). To quantify the rate of deletion of different-sized fragments, we used a qPCR strategy with a primer pair designed to amplify the segments corresponding to the genome copies that did not undergo targeted deletion. Another pair of primers was used to amplify a region in the GAPDH gene as a control. As expected from enUn1Cas12f1’s superior single site-editing activity when compared to enAsCas12f (see Supplementary Fig. 6A–D), it generally drove more efficient fragment deletions programmed by a pair of sgRNAs (Supplementary Fig. 9A). Furthermore, enUn1Cas12f1 presented similar activities as SpCas9 for fragment deletions (Supplementary Fig. 9B). Collectively, these results highlighted the potential of enUn1Cas12f1 as a highly useful addition to the CRISPR toolbox. Given its miniature property, it would be particularly suitable for many therapeutic applications with strict constraints on vector size.

Applications of enUn1Cas12f1 for in vivo editing and for transcriptional regulation

Our optimized enUn1Cas12f1 exhibited high DNA double-strand cleavage efficiency, and its compact structure enables packaging of both the expression cassette and corresponding sgRNA into a single AAV vector34. This capability facilitates potential in vivo therapeutic applications for genetic or acquired diseases. Previously, in vivo genome editing-dependent knockdown of TTR gene was developed as a promising treatment strategy for transthyretin amyloidosis35,36. As the TTR is expressed primarily from the liver, the use of a single AAV-based liver-targeting Cas12f vector could represent a practical and safe therapeutic strategy with strong application potential. Therefore, we subjected AAV8 vector-delivered enUn1Cas12f1 to in vivo tests for editing the Ttr gene in mice. We first evaluated the editing efficiencies of enUn1Cas12f1 and the wild-type Un1Cas12f1 at multiple target sites within the Ttr gene in N2a cells (Fig. 3A). It is interesting to note that while enUn1Cas12f1 presented consistently superior activities, the differential activity patterns across the sgRNA panel did not always show strong correlations between the WT Un1Cas12f1 and enUn1Cas12f1 groups. Indeed, the sgRNA-SITE10 presented the highest activities with enUn1Cas12f1, but minimal activities with the WT Un1Cas12f1, reflecting the apparent fitness of this sgRNA in the enUn1Cas12f1 context. We subsequently selected sgRNA-SITE10 for in vivo editing experiments. A single AAV8 vector was engineered to express enUn1Cas12f1 (or WT Un1Cas12f1) under the HCRhAAT promoter, and sgRNA-SITE10 under the U6 promoter (Fig. 3B). Mice were injected with the AAV vector, and blood samples were collected at 0, 4, 6, and 8 weeks to measure serum transthyretin protein levels. The results showed that at two different doses (3 × 1011 and 1 × 1012 viral genome, vg), the enUn1Cas12f1 vector, but not the Un1Cas12f1 vector substantially reduced plasma transthyretin levels compared to the control mice (Fig. 3C). The higher dose led to a trend of more effective reduction of plasma transthyretin than the lower dose at 6 and 8 weeks after treatment, although the differences did not reach statistical significance. After eight weeks, the mice were sacrificed, and liver tissues were collected for genomic DNA extraction, followed by target site PCR and NGS sequencing. The results demonstrated that while the Un1Cas12f1 vector did not cause evident indels at Ttr in mouse liver, the two doses of enUn1Cas12f1 vector induced ~30 and ~60% edits, respectively (Fig. 3D). The much-improved activities with enUn1Cas12f1 over the WT editor for this sgRNA was consistent with the in vitro test (see Fig. 3A). These results strongly suggested the potential of enUn1Cas12f1 for efficient in vivo disease gene targeting toward a durable therapeutic response.

A Indel frequencies comparison between Un1Cas12f1 and enUn1Cas12f1 at numerous target site in N2a cells. Data were obtained from biological replicates (n = 3) and are presented as mean ± SD. The site selected for subsequent in vivo editing is marked in red. B Schematic illustration for administration of AAV8-packaged Un1Cas12f/enUn1Cas12f1 in mice for liver genome editing. C Levels of plasma transthyretin levels at different time points following AAV administration to mice (male). Data were obtained from biological replicates (n = 4) and are presented as mean ± SD. D Analyses of indel frequencies at the Ttr target site in samples from mouse livers. Data were obtained from biological replicates (n = 4) and are presented as mean ± SD. E The illustration indicates the principle of measuring CRISPRa activity with a reporter system. Different spacer sequences were incorporated upstream of the miniCMV promoter, which were targeted by (en)Un1Cas12f1-VPR to drive EGFP expression. A plasmid encoding BFP was co-transfected as a control for transfection efficiency. F The bar plot shows the fold changes in the relative EGFP fluorescence (quantitated as mean fluorescence intensity, MFI) over that of BFP, in response to targeting by enUn1Cas12f1-VPR and the wild-type counterpart. Data were obtained from biological replicates (n = 3) and are presented as mean ± SD. G The scheme illustrates enUn1Cas12f1-VPR-dependent targeting at different locations upstream of the transcription start site of the IFNG gene to activate its expression. H.Relative expression levels of IFNG mRNA in HEK293T cells by enUn1Cas12f1-VPR compared to wild-type controls, measured by qPCR. The measurements of GAPDH mRNA were used as internal references to normalize expression levels. Data are presented as mean ± SD from biological replicates (n = 3). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Beyond DNA cleavage, CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) systems based on SpCas9 or other smaller Cas proteins have proven effective for targeted rewiring of genetic circuits16,37. To evaluate the potential of enUn1Cas12f1 in CRISPRa applications, we introduced D326A and D510A nuclease-inactivation mutations into enUn1Cas12f1 and constructed the dCas12f1-VPR (VP64-p65-Rta) CRISPRa activator16. A reporter system was constructed by placing a customized target sequence upstream of a miniCMV-EGFP cassette (Fig. 3E). A total of three different target sequence-led reporters were tested. To normalize the transfection efficiency, we also introduced a plasmid for constitutive BFP expression. Forty-eight hours after transfection of HEK293T cells with the reporter together with the CRISPRa components based on enUn1Cas12f1 or UniCas12f1, the cells were subjected to FACS. The activation efficiency was quantified by the ratio of GFP fluorescence intensity to BFP fluorescence intensity. The results showed that the enUn1Cas12f1-CRISPRa outperformed the Un1Cas12f1 counterpart on all three reporters (Fig. 3F). To test the CRISPRa-driven activation of an endogenous target, we chose the gene encoding IFNγ, whose targeted activation could potentially drive an anti-tumoral therapeutic response. To this end, two guide RNAs targeting distinct locations near the transcription start site of the IFNγ gene were designed (Fig. 3G). The HEK293T cells were transfected with the CRISPRa components based on enUn1Cas12f1 or Un1Cas12f1. With both sgRNAs, although Un1Cas12f1-VPR only drove minimal IFNG activation, enUn1Cas12f1-VPR caused hundreds-fold induction of IFNG mRNA (Fig. 3H). Together with the results from experiments with AAV deliveries, the above results on transcription activation supported the application potential of enUn1Cas12f1 in diverse contexts.

TS cytosine editing by Un1Cas12f1-evoCDA1

CRISPR/Cas-derived BEs have received strong consideration for development as a precise editing tool without the requirement of double strand DNA break (DSB). Given the present establishment of the high-activity enUn1Cas12f1, we sought to examine its potential for development into a small-sized base editor. First, we systematically evaluated the C-to-T editing efficiency of a series of BEs constructed with the non-enhanced version of Un1Cas12f1, or two other Cas proteins, i.e., SpCas9 and LbCas12a (all in their nuclease-dead forms), in combination with several commonly used cytosine deaminases (evoCDA1, rAPOBEC1, hA3A (Y130F), and Anc68938). Two genomic loci were targeted for editing (Fig. 4A). After transfecting cells for 72 h, the top 15% cells were sorted using flow cytometry for preparation of genomic DNA. The results showed some apparent variability in dCas protein/deaminase compatibility for C-to-T editing. Evident activities were observed for 3, 2 and 1 BEs with the targeting modules of dCas9, dLbCas12a and dUn1Cas12f1, respectively. Of all deaminases tested, evoCDA1 exhibited the most consistent activities and was compatible with all three dCas proteins for C-to-T edits (Fig. 4A). As a commonly used BE component38, the unfavorable activities of Anc689 (including the dCas9-based editor) in these assays might be particular to the sites tested. We next proceeded to determine the effects of the enhancement mutations on the BE activities. The unmodified or enhanced BEs (dUn1Cas12f1) with either evoCDA1 or Anc689 were tested on three genomic sites. Indeed, regardless of the coupled deaminases, the d-enUn1Cas12f1-dependent BEs showed substantially enhanced C-to-T editing activities over the counterpart with dUn1Cas12f1 (Supplementary Fig. 10). These results highlighted the potential of the enUn1Cas12f1 protein moiety for base editing applications.

A Comparisons of activities at two genomic loci by different BEs featuring various Cas and deaminase pairs. All mutations are described in reference to the NTS sequence, where G-to-A substitutions indicate C-to-T editing on the TS. Such denotation is used throughout the data presentations unless stated otherwise. B The bar graph shows the editing efficiency of dUn1Cas12f1-evoCDA1 at multiple sites in HEK293T cells. The C- and G-edits are presented in yellow and blue bars, respectively. Data were obtained from biological replicates (n = 3) and are presented as mean ± SD. C Summary of C-to-T or G-to-A editing efficiency (in reference to NTS bases). All individual measurements from three biological replicates at various edited bases are plotted. Each data point reflects a measurement of C-to-T edits (n = 15 positions × 3 replicates) or G to A edits (n = 11 positions × 3 replicates) shown in (B). The median values from all C to T edits or G to A edits are indicated by the black horizontal lines. D The top part shows an overview of site-specific base transitions and transversions introduced by various existing base editors. The lower part of the panel illustrates the conceptual outcome from induction of target strand base editing, with the target base highlighted in red. E The scheme illustrates the potential mechanism of how nuclease-dead (en)Un1Cas12f1-evoCDA1 could achieve C-to-T editing on the target strand, with a key step involving the exposure of an ssDNA segment in the TS. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Close examination of base conversion profiles of dUn1Cas12f1-evoCDA1 revealed another surprising trend. Besides the C-to-T conversions, the profiles also presented visible levels of G-to-A edits, whereas such edits were rarely observed in the editing products of dCas9-based counterparts (Fig. 4A). To assess the generalizability of NTS G-to-A editing by dUn1Cas12f1-evoCDA1, we tested its activity at multiple genomic loci in HEK293T cells. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) results revealed that most sites exhibited NTS G-to-A editing, although the efficiency was lower than C-to-T observed on the NTS (Fig. 4B, C and Supplementary Fig. 11). As dLbCas12a-evoCDA1 also appeared to yield low levels of edits at certain G bases (Fig. 4A), we expanded the analyses to several additional sites. The results confirmed that dCas12-based editor could support low levels of G-to-A edits (Supplementary Fig. 12). Given the nature of evoCDA1 as a cytosine deaminase, these results suggest that, besides the catalytic activity at C on the NTS, the deaminase appeared to act specifically with the type V Cas12 family to drive C-editing action on the TS. Importantly, we found that compared to the control dUn1Cas12f1-evoCDA1, the d-enUn1Cas12f1 version also showed clearly increased levels of G-to-A edits (Supplementary Fig. 10), which further implicates the key role of specific, Cas12f1-dependent DNA targeting in such unconventional edits. The lack of TS editing by the Anc689-adapted dUn1Cas12f1 or d-enUn1Cas12f1 in these initial tests might be caused by certain restraints on structural compatibilities in combination with sub-optimal deaminase activities or sequence contexts.

Although rare events of out-of-protospacer TS editing had been reported with nCas9-based BE39, in the present system, most of the TS editing by dUn1Cas12f1-evoCDA1 was within the spacer sequence (see Fig. 4A and Supplementary Figs. 10, 11). Such an activity could provide good opportunities to expand the editable scope for C:G to T:A conversions (Fig. 4D). Although the more recently developed G-editing BEs could complement CBEs to edit additional C:G pairs, their editing products are promiscuous. Therefore, taking such in-window G bases as an example, a great majority of them cannot be easily converted to A via the use of canonical CBE (Supplementary Fig. 13). Therefore, the presently unveiled activity of dUn1Cas12f1-evoCDA1 to drive C-to-T editing directly on the TS could significantly broaden the applicability of cytosine BEs.

While the dUn1Cas12f1-evoCDA1-driven, direct TS editing was initially surprising, a closer survey of the reported structural dynamics on the Cas12 family-mediated cleavage provided some insights on the underlying molecular mechanisms. Different from a Cas9 nuclease that mediates NTS and TS cleavage, respectively, by its RuvC domain and HNH domain, a Cas12-family nuclease employs a RuvC domain to cleave both the NTS and TS. Such a share-of-duty by the RuvC domain in a Cas12 family nuclease would imply unique structural determinants for TS cleavage. Indeed, current studies with Cas12a suggest that TS cleavage requires partial unwinding of the TS region near the end of the spacer40,41,42,43,44. Subsequently, the unwound, single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) segment of TS could enter the RuvC catalytic center for cleavage. For the smaller-sized Cas12f1, although they act in a dimer form, only one single RuvC domain in the dimer is positioned close to the substrate DNA and can mediate cleavage of both NTS and TS45,46. Since Cas12f1 proteins drive out-of-protospacer cleavage (~22–24 bp from the PAM) on both NTS and TS15,17,47, the above-mentioned downstream DNA unwinding events appear particularly relevant48. Furthermore, several studies have also demonstrated that Cas12a R-loops are dynamic and heterogenous in size42,49,50. Regarding Cas12f1, the fact that a truncated guide RNA spacer as short as ~16–17 nt could program efficient downstream cleavage15,17,47 also implied the dynamic sizes of Cas12f1 R-loop even given a standard-sized spacer. The combination of R-loop (heteroduplex) dynamics and apparent downstream DNA breathing upon Cas12 family targeting could facilitate an extended, PAM-distal TS segment to potentially adopt ssDNA conformation. Therefore, we propose that when dUn1Cas12f1 enables part of the TS to dynamically adopt such ssDNA conformation, the latter could become a substrate for deaminase-mediated cytosine editing (Fig. 4E). Indeed, the overall positioning of the G-to-A editing window on the 3′-end side of the target site is highly consistent with this mechanistic model (see Fig. 4A and Supplementary Figs. 10, 11). Collectively, our investigations thus far unveiled that dUn1Cas12f1-evoCDA1 exhibited both NTS- and TS-editing activities, which could be co-improved by the enhancement mutations featured in enUn1Cas12f1.

Further engineering of Un1Cas12f1-derived base editor to promote TS cytosine editing via a reprogrammed nickase activity

As TS editing by evoCDA1-adapted dCas12f1 BEs thus far was generally less efficient than NTS editing (see Fig. 4A, Supplementary Figs. 10, 11), to selectively potentiate installation of TS edits, we sought additional engineering measures. In the commonly applied BEs, the employment of a nickase Cas9 acting on the TS (deficient in the RuvC domain activity) could direct the cellular repair to eventually install the edit according to the modified NTS, which could substantially promote base-editing activities over the full nuclease-dead BE2. Therefore, we conceptualized that an opposite, NTS-nicking form of Un1Cas12f-evoCDA1 could preferentially potentiate TS edits over NTS edits. However, owing to the dependence of Cas12s on a single RuvC domain for dual-strand cleavage, previous Cas12 family BEs were mostly constructed upon the full nuclease-dead Cas12s51,52. Nevertheless, given the NTS-to-TS sequential cleavages by Cas12s/RuvC domain42,48, we reasoned that it might be possible to screen for mutant Un1Cas12f1/evoCDA1 forms that are deficient in TS cleavage.

Based on the convenience of NGS targeted sequencing on pooled samples, we took a direct screening approach to determine the base editing activities of various mutant forms of enUn1Cas12f1-evoCDA1. Drawing on structural and functional studies of Un1Cas12f1, AsCas12f, and Cas12a proteins17,25,27,45, we carried out an alanine scan within the nuclease (NUC) lobe structure formed by the RuvC and TNB domains of enUn1Cas12f1-evoCDA1. Interestingly, the NGS results showed that ~ one-third of the 75 tested mutants showed greater levels of G-to-A editing (C-to-T TS editing) and concomitant decreases in canonical C-to-T editing, when compared with d-enUn1Cas12f1-evoCDA1 (Fig. 5A). We considered these variants as our primary hits. However, further analyses revealed that numerous such primary hits still retained double-strand DNA cleavage activities reflected by the indels (Supplementary Fig. 14). Given the relatively frequent hits among cleavage-competent enUn1Cas12f1-BE variants, we reasoned that the intrinsic stepwise NTS- and then TS- cleavage property of Un1Cas12f148 might have licensed these various “nuclease-BE” derivatives with TS-prone features. As only the variants with minimal indel-forming activities were desirable, we sought to test the effects of double-substitution in enUn1Cas12f1-BE on the base-editing and indel-forming activities. We selected several primary hits (V327A, F435A, K473A) with a promising pattern of low indels, and two other hits (N423A and L481A) with some indels. First, the F435A mutation was combined with other 12 primary hits to construct double substitutions. Moreover, selected combinations between V327A, N423A, K473A and L481A, and several other V327A- or N423A-involving double substitutions were prepared. These 20 double-substituted variants were subjected to targeting two genomic loci (Supplementary Fig. 15A). Consistent with the low to moderate indel rates of the core single-substitution mutants (V327A, N423A, F435A, K473A and L481A), the tested double-site variants largely showed low indel rates (Supplementary Fig. 15B). Notably, among these double-site mutants, several of them showed greater enhancement of G/A in expense of C/T edits (Supplementary Fig. 15A). We selected two of the favorable double-site mutants (V327A-K473A, L481A-N423A) for further analyses.

A Alanine scan mutagenesis was performed at the nuclease lobe (red in ribbon diagram) of Un1Cas12f1 to screen for enUn1Cas12f1-BE variants favoring G-to-A edits. In the linear display of domain assembly, the residues corresponding to the start and end sites of each sub-motif constituting the nuclease lobe structure are printed in red. The right heatmaps present G-to-A and C-to-T editing efficiencies at two sites (NTS) for different mutants (mean from three biological replicates). B G-to-A editing at six sites (for every G) by enUn1Cas12f1-evoCDA1 variants or the controls. Each data point represents the average from three biological replicates. The dot plot further summarizes the combined G-to-A editing efficiency within the presently defined window (positions 12 to 25) at all sites. The black line indicates the overall average rate (33 Gs). C The editing window summary was determined from results in (B). Conversion rates at indicated positions at all sites are averaged as a data point for each editor. The measurement numbers corresponding to individual positions are marked below. D Analysis of G-to-A and C-to-T efficiency and editing window of TSminiCBE (top-performing enUn1Cas12f1 (K473A)-evoCDA1 variant in (B)), and another variant in HeLa and AGS cells across 12 different sgRNAs. The graph is prepared as in (C). E Indel frequencies from experiments in (D) are summarized. Each data point reflects a single measurement (n = 12 sites × 3 replicates) for each indicated group (black lines: medians). F To evaluate editing motif (NGN) preference, the HMG-TSminiCBE editing results with 50 sgRNAs in HEK293T cells were summarized in regards to all available motifs (number of data point per motif marked below the violin plot). The editing window was set as in (B). Each data point represents the average from three biological replicates. The medians for each motif are indicated by black lines. G Editing window analyses for results in (F) are presented similar as in (D), except that all data points for G (blue) and C (gray) at each position are displayed (black lines: medians). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

From the pool of hits above, we subjected four single-site mutants (V327A, F435A, K473A and L481A), and the V327A-K473A and L481A-N423A double-site mutants to a secondary screen at additional genomic loci in HEK293T cells. Dead enUn1Cas12f1-evoCDA1 and Un1Cas12f1 (L481A)-evoCDA1 were used as control groups. These variants were compared on the basis of their G-to-A editing efficiency, product purity (reflecting the preference of G/A over C/T edits), as well as the indel rates (Fig. 5B and Supplementary Fig. 16A, B). It is worth noting that although the indel rates by these BE variants were generally low (between 0.5% to 3%), they were elevated in comparison to those by the nuclease-dead, d-enUn1Cas12f1-CDA1 (Supplementary Fig. 16C). With all above parameters considered, we selected the K473A variant as the optimal choice and subsequently designated the enUn1Cas12f1 (K473A)-evoCDA1 variant as TSminiCBE (TS Mini Cytosine BE). TSminiCBE not only presented top-level TS-editing activities, but also featured relatively limited indel rates [~2%, with edit/indel ratio at ~20] (Supplementary Fig. 16C).

When G-to-A or C-to-T edits at all available positions were summarized for TSminiCBE, a robust, distal protospacer (position ≥13) G-to-A editing window and a lower-level, scattered C-to-T editing window with some preferences for PAM-proximal positions could be established (Fig. 5C). As the nuclease-dead control editor, d-enUn1Cas12f1-evoCDA1 covered similar base positions, but induced G-to-A and C-to-A edits at the distal bases (position ≥13) with respectively less and greater efficiencies compared with TSminiCBE. We also noted some G edits by TSminiCBE downstream of the protospacer, at position 21–23. In contrast, the out-of-protospacer edits by d-enUn1Cas12f1-evoCDA1 were minimal, likely owing to its overall suboptimal activities for G edits. These data were again consistent with our model that a temporary Cas12f1 conformation-driven TS unwinding near the 5′-end of the targeted sequence is key to evoCDA1-dependent TS editing (see Fig. 4E).

Next, to evaluate the versatility of TSminiCBE, we tested its performance in HeLa and AGS cells and compared it with another promising single mutation, V327A. NGS results from 12 endogenous loci were summarized. In HeLa cells, TSminiCBE achieved an average editing efficiency of 40%, with the G-to-A product purity exceeding 80% and average indel rates below 6%. In AGS cells, the average editing efficiency was 30%, with the G-to-A product purity of 80% and average indel rates below 5% (Fig. 5D, E and Supplementary Fig. 16D). Like in HEK293T cells, a distal G-to-A editing window, and a lower-level, scattered C-to-T editing window (with some preferences for PAM-proximal positions) of TSminiCBE was also confirmed in these additional cell types. TSminiCBE was also applied to editing mouse N2a cells. Quite similar pattern of efficient G-to-A editing, high product purity and minimal indels were observed (Supplementary Fig. 17). Together, our results established an improved TS-editing Cas12f1 BE (TSminiCBE), which showed enhanced G-to-A editing efficiency and product purity, while maintaining low indel rates in multiple cell types.

To validate that the K473A mutation of enUn1Cas12f1-evoCDA1 improved G-to-A edits via a nickase action, we first carefully compared the editing products by TSminiCBE and the d-enUn1Cas12f1-evoCDA1 (Supplementary Fig. 18A). Indeed, the individual reads from the nuclease-dead base editor mostly belonged to either the exclusive C-to-T or G-to-A types, consistent with the notion that the cellular repair tends to accept one strand or the other for the eventual installation of C:G to T:A edits. Due to our focuses on TS editing, the test loci were selected to feature G base-enrichment near the 3′ end of the targeted sequence (compared with the earlier NTS C base-oriented targets, see Fig. 4A and Supplementary Figs. 10, 11), apparently causing favorable G/A- to C/T-editing ratios with the d-enUn1Cas12f1 BE (Supplementary Fig. 18A). Besides these typical editing products, a minor portion of the reads contained both C-to-T and G-to-A edits which were likely caused by yet-to-be-defined editing mechanisms (see “Both” columns in Supplementary Fig. 18A). In regard to editing products from TSminiCBE, the C/T- and G/A-exclusive reads showed substantial, anti-correlated decrease and increase in comparison to the control group, respectively. On the other hand, the reads with concomitant C/T and G/A edits were largely unchanged (Supplementary Fig. 18A). These results strongly support the role of TSminiCBE in promoting acceptance of TS-biased editing products. The kinetics of overall C/T or G/A edits by TSminiCBE were also determined (at 24, 48, 72, 96 h). Both types of edits reached near-plateau levels at 48 h (Supplementary Fig. 18B). We again separated C/T-only, G/A-only and concomitant C/T and G/A reads, and analyzed their percentages across the time points. The percentages of TSminiCBE’s editing products in the three groups remained unchanged over time (Supplementary Fig. 18C), suggesting that TSminiCBE might independently edit NTS or/and TS in cells. Therefore, the concomitant C/T and G/A reads were unlikely to result from sequential installation of edits on one and then the other strand.

Next, to further assess the potential nickase activity by TSminiCBE, we took advantage of a previously established reporter system that could be used to dissect the DSB- and nick-forming activities by nuclease variants21. The EGFP-based reporter features separated, non-functional 5′ and 3′ half-EGFP segments. The intervening segment contained a nuclease-cleavable block flanked by homologous sequences, which could be induced by the nuclease action to recombine with each other. This could lead to restoration of EGFP function (Supplementary Fig. 19A). For a candidate nuclease, a reporter with a single nuclease-target site could be used to assess DSB-forming activities. The combined use of such a DSB reporter (single-site), and another nickase reporter containing a complementary pair of the target sites (dual-site) would collectively inform nick-forming activities (Supplementary Fig. 19A). We subsequently tested various forms of enUn1Cas12f1 (WT and K473A) and the derivative TS-editing BEs on these reporters.

As expected, the WT enUn1Cas12f1 showed equivalent reporter-restoring activities on the single-site and dual-site reporters, which confirms the DSB-forming capability of the WT nuclease (Supplementary Fig. 19B, the 2nd group). Interestingly, we found that the K473A-substituted enUn1Cas12f1 also retained significant activity to restore the single-site reporter, although its activity on the dual-site reporter was comparably higher (the 3rd group). As the conversion of the dual-site reporter may reflect the combined DSB- and nick-forming activity, these results suggested that the K473A-substituted enUn1Cas12f1 became a partial nuclease/nickase. Moreover, for enUn1Cas12f1-derived BE (with evoCDA1), its activities on the one-site and dual-site reporters were similarly dampened in comparison with the nuclease-only form (see the 2nd and 4th groups), which implied an interference of the deamination reaction on the Cas12f1-dependent DSB formation. Consistent with this notion, the K473A-substituted enUn1Cas12f1-evoCDA1 (i.e., TSminiCBE) became largely deficient on the one-site reporter, possibly driven by a cooperation of K473A- and deaminase-dependent inhibition of DSB-forming activity. On the other hand, TSminiCBE retained an evident activity to convert the dual-site reporter (Supplementary Fig. 19B, the 5th group). Therefore, these results validated our earlier assumption regarding the cleavage profile of TSminiCBE, where it predominantly acts a nickase, but not a nuclease.

To functionally link the enhancement of TS editing by K473A-substituted enUn1Cas12f1-evoCDA1 (TSminiCBE) to biased strand cleavage, we introduced the nuclease-inactivation mutations (D326A-D510A) into TSminiCBE. Importantly, unlike TSminiCBE, its nuclease-dead form (still with K473A) showed much reduced G-to-A edits, and anti-correlated increases in C-to-T edits, with its performances becoming very similar as the d-enUn1Cas12f1-evoCDA1 (Fig. 5B, C and Supplementary Fig. 16A). These results strongly corroborate the role of K473A-dependent establishment of NTS nick formation in driving the potent activity of TSminiCBE.

In conjunction with robust G-to-A base edits, TSminiCBE could induce some low levels of indels (see Supplementary Fig. 16C). We sought to probe whether combined TS deamination and NTS nicking by TSminiCBE was causative to such undesirable effect38. Therefore, we closely examined the characteristics of TSminiCBE-associated indels (samples shown in Supplementary Figs. 14 and 16B). The patterns of enUn1Cas12f1 nuclease-induced indels at the same sites were considered as controls (samples shown in Supplementary Figs. 4D and 6A). As expected, enUn1Cas12f1 yielded much higher levels of indels than TSminiCBE (Supplementary Fig. 20A). Furthermore, enUn1Cas12f1-induced indels showed a typical pattern featuring abundant deletions at sizes of 10−25 bp (Supplementary Fig. 20B). Quite interestingly, a distinct class of smaller-sized deletions (<7 bp) was prevalent in TSminiCBE-associated indels. Indeed, some major indel alleles induced by TSminiCBE (unlike those by enUn1Cas12f1) presented smaller-sized deletions around the 3′ end of the protospacer (Supplementary Fig. 20A). These TSminiCBE-characteristic indels were apparently located near the site(s) of TS deamination (corresponding to G in NTS), analogous to the indel signature associated with Cas9-derived BEs53. Collateral G-to-A edits were observed in the same TSminiCBE indel alleles (Supplementary Fig. 20A). Such distinctive patterns suggest that TSminiCBE-dependent deamination/nicking can cause low incidences of DSB and indels, which represents a minor tradeoff for its enhanced activities (in reference to the nuclease-dead BE version). However, similar to the previous refinements on classical BEs, we propose that future implementation of optimized inhibitory module against the base-excision repair could mitigate such undesirable effect53,54.

Thus far, we had focused on exploring the evoCDA1-adopted Un1Cas12f1 BEs, mainly because the initial compatibility of evoCDA1 with dUn1Cas12f1 to induce G-to-A conversions (Fig. 4A and Supplementary Fig. 10). We therefore sought to confirm that K473A-substituted enUn1Cas12f1 could serve as a common module to enable TS editing by other ssDNA-targeting deaminases (rAPOBEC1 or Anc698), though likely with lower activities. First, two tested target sites of the evoCDA1/TS BEs (at GAPDH and VEGFA, see Fig. 5B) were subjected to editing with rAPOBEC1-fused d-enUn1Cas12f1. PAM-distal side G-to-A edits were visible, with the top rates within tested Gs at ~1% and ~10% for the two sites, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 21A). In parallel, we also introduced a non-fusion version of d-enUn1Cas12f1/sgRNA together with a separate construct of rAPOBEC1-UGI (or evoCDA1-UGI), since a similar “orthogonal R-loop assay” was previously employed to probe the deaminase-intrinsic access to pre-formed ssDNA55,56,57,58. Indeed, our results showed that free rAPOBEC1 (or evoCDA1, to a greater extent) could also induce detectable levels of G-to-A edits at d-enUn1Cas12f1 target sites, in conjunction with canonical C-to-T edits. Importantly, although the events of pre-conditioned TS edits (G-to-A) by free rAPOBEC1 appeared fewer than those triggered by d-enUn1Cas12f1-rAPOPEC1 fusion, the two approaches showed similar location-dependent editing patterns (Supplementary Fig. 21A). These results provided further evidence that d-enUn1Cas12f1 targeting was associated with induction of ssDNA conformation near the PAM-distal end of the TS. We subsequently proceeded to test whether establishing biased strand cleavage as in TSminiCBE (with a K473A-enUn1Cas12f1 module) could also transform rAPOBEC1- or Anc689-equipped Cas12f BEs into more effective TS-editing forms (Supplementary Fig. 21B). K473A-enUn1Cas12f1-rAPOBEC1 showed substantial activities for G-to-A edits (top-edited Gs from ~10% to ~50% at four sites), and quite insignificant levels of C-to-T edits (Supplementary Fig. 21C). The Anc689-adopted K473A-enUn1Cas12f1 BE showed similar results (with rates of >30% at top-edited Gs). Such G-to-A-editing activities clearly eclipsed those by the d-enUn1Cas12f1-deaminase fusion forms (see Supplementary Fig. 21A and Supplementary Fig. 10). Overall, these results demonstrated the general adaptability of K473A-substituted enUn1Cas12f1 with multiple deaminases to enable efficient G-to-A edits.

Adoption of additional DNA-binding motif to improve editing by TSminiCBE

Previous studies have shown that incorporation of non-specific DNA binding proteins could improve base editing efficiency59,60,61. To further enhance the performance of TSminiCBE, we tested the strategy of equipping BE with additional non-specific DNA-binding domains. To this end, two commonly used non-specific DNA-binding proteins, i.e., Sso7d and HMG-D, were respectively fused with the N-terminus or C-terminus of TSminiCBE, or placed in between the deaminase and Cas12f1 moieties (Supplementary Fig. 22A). The editing efficiencies by various motif-supplemented TSminiCBEs were evaluated at three genomic loci in HEK293T cells. The results showed that the placement of HMG-D or Sso7d between the deaminase and enUn1Cas12f1 (K473A) represented the first and second highest configurations to enhance TSminiCBE activity (Supplementary Fig. 22B–D). It is worth pointing out that these enhancement strategies did not affect the windows of G-to-A editing. We consequently applied the top-ranked variant (HMG-TSminiCBE) to extensive tests at 12 additional genomic loci in HEK293T cells. The results confirmed that HMG-TSminiCBE presented greater editing efficiency and product purity than TSminiCBE, and revealed a slight downside of the HMG-editor in its indel rates, which nonetheless remained low (Supplementary Fig. 23).

To further explore the sequence motif preference and editing window of HMG-TSminiCBE, we tested its activity at 50 genomic loci in HEK293T cells (Fig. 5F, G). NGS results demonstrated that HMG-TSminiCBE exhibited no specific preference for NGN sequences, with its editing window located between the 11th and 25th bases from the 3′ of the PAM sequence (Fig. 5F, G and Supplementary Fig. 24). To explore the effect of the length of sgRNA/target base pairing on TS editing by HMG-TSminiCBE, we designed sgRNAs ranging from 17 to 22 bp in length (Supplementary Fig. 25A). The NGS results showed that sgRNA spacer as short as 17 bp (vs 20 bp) did not substantially affect the G-to-A editing window, efficiency and the G/A-over-C/T preference, or lead to changed indel levels (Supplementary Fig. 25B, F). However, extending the sgRNA to 22 bp resulted in a significant decrease in editing efficiency. These overall patterns appear consistent with previous observations in Cas12f1-dependent cleavage experiments15,17.

The robust read-out by HMG-TSminiCBE also made it a suitable system to further probe the mechanisms underlying the TS editing activity. To confirm the role of R-loop dynamics in Cas12f1-BE TS editing, we considered to experimentally perturb R-loop propagation, via creating PAM-distal targeting mismatches41,62. The latter mismatch(es) could act as a brake to shift the positional distribution of the forward R-loop boundary, and subsequently impact on base-editing profiles (Supplementary Fig. 25C). To this end, we introduced single mismatches respectively at positions from 15 to 19 for each sgRNA (a total of 4 different guides). Cells were transfected with HMG-TSminiCBE and respective sgRNAs. G-to-A edits at all target positions were determined. A largely consistent pattern emerged from these experiments. A single mismatch at positions from 17 to 19 mainly inhibited downstream G-to-A edits (~ G18–20), but not upstream edits (~ G12–G16) (Supplementary Fig. 25D, E). Such an apparent slide of TS-editing window by the distal mismatches (position 17 to 19) indeed supports the role of R-loop propagation dynamics (and boundary-DNA breathing) in licensing the G-to-A editing by Cas12f1-BE. Moreover, these results also presented a facile method to narrow the G-to-A editing window. On the other hand, a single mismatch at position 15 or 16 mostly led to reduced G-to-A editing at all positions, which was likely attributed to the fact that more upstream sgRNA/DNA mismatches could compromise Cas12f1-dependent DNA targeting in general (Supplementary Fig. 25D, E).

Given the superior TS editing activities of HMG-TSminiCBE attributed to Cas12f1 improvement, NTS nicking activity, and HMG motif-dependent DNA interaction, we next applied it to in vivo base-editing experiment. The gene of fatty acid synthase (FASN) was chosen as a test target, since it had been recognized as a potential therapeutic target for metabolic diseases63. Herein, we examined the capability of AAV-packaged HMG-TSminiCBE/sgRNA for installing a premature stop codon at Fasn gene in mouse liver (Supplementary Fig. 26A). In a cell-based test (mouse N2a cells), we confirmed that TSminiCBE/sgRNA led to multiple G-to-A substitution at the target site, with a ~ 60% rate for the top edit (position-19) corresponding to introduction of a stop codon (Supplementary Fig. 26B). Subsequently, the AAV vector-packaged HMG-TSminiCBE/sgRNA was administered to mice (1×1012 viral genome). Following editing (8 weeks), the liver samples were harvested for NGS analyses. We found that consistent with the results in mouse N2a cells, the AAV vector-delivered HMG-TSminiCBE also led to evident G-to-A editing at the target site, with a ~ 25% rate for the top edit (Supplementary Fig. 26B). Although the editing rate in vivo was lower than that in cultured cells, the position-wise distributions of multiple G edits were similar between the experiments (Supplementary Fig. 26B). Moreover, the editor induced few C edits in either context. These results demonstrated the potential of our developed Cas12f1-BE to mediate TS editing in vivo.

The fidelity of enUn1Cas12f1 and TSminiCBE-mediated genome editing

To assess the editing fidelity of TSminiCBE, we first focused on the enUn1Cas12f1 component. For the targeting at two genomic loci, within CCDC127 and COL8A1, we introduced a series of single or side-by-side double mismatches into the sgRNA spacer sequence (Supplementary Fig. 27A). The editing rates (indels) by Un1Cas12f1 and enUn1Cas12f1 together with the control or various mismatched sgRNAs were examined. In an expected, general pattern, the mismatches between the guide RNA and the target inhibited editing rates, as double mismatches were less tolerated than single mismatches (Supplementary Fig. 27A). When compared to Un1Cas12f1, enUn1Cas12f1 generally showed higher tolerance to single and double mismatches, which could be reasonably anticipated from its more potent activities. Nevertheless, PAM-proximal double mismatches strongly mitigated the editing by enUn1Cas12f1 (Supplementary Fig. 27A).

We further examined the off-target activities of enUn1Cas12f1 at the in silico predicted sites. For sgRNAs targeting sites at CCDC127 and COL8A1, eight potential off-target (OT) sites were predicted via Cas-OFFinder. Targeted NGS showed that only near-baseline levels of sequence variances across these sites, with little difference between WT Un1Cas12f1 and enUn1Cas12f1 groups (Supplementary Fig. 27B). Next, whole genome sequencing (WGS) was performed on genomic DNA. Cells transfected with the EGFP plasmid were set as a control of genomic variants in the transfected cells. Both the Un1Cas12f1 and enUn1Cas12f1 groups exhibited similar numbers of single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) and indels as the EGFP control group (Supplementary Fig. 27C). The distribution of these variants across the genome in relation to functional genetic units also exhibited consistent patterns among different groups (Supplementary Fig. 27D). Additionally, a circos plot displaying mutations on genomic coordinates revealed that most such indels and SNVs were located at mutation hotspots, and no significant differences existed between the enUn1Cas12f1 and Un1Cas12f groups (Supplementary Fig. 27E).

Nevertheless, given the likely limited sensitivity of whole-genome sequencing for calling off-target events, we employed GUIDE-seq64, a method with higher detection sensitivity, to evaluate the off-target activity of enUn1Cas12f1 (with sgRNAs targeting CCDC127 and COL8A1). Such a sensitive approach indeed captured off-target editing events by enUn1Cas12f1 at a number of unintended sites for both sgRNAs (Supplementary Fig. 27F, left). The OT sites presented apparent sequence similarities as the target site. Based on GUIDE-seq profiling, we focused on five (sgRNA-COL8A1) and four (sgRNA-CCDC127) top-ranked OT sites, and further compared their hit rates by enUn1Cas12f1 and its WT counterpart via targeted NGS. The on-target rates were also measured. enUn1Cas12f1 provided variable levels of on-target activity improvements over Un1Cas12f1 at the two sites (1.15- and 2.7-fold). However, as a tradeoff, enUn1Cas12f1 exhibited higher OT rates, averaging to 3.6- and 3.9-fold increases with the two respective sgRNAs. Consequently, enUn1Cas12f1 raised the normalized off-target editing rates (relative to on-target rates) by 3.3- and 1.4-fold over WT Un1Cas12f1 with the two sgRNAs (Supplementary Fig. 27F, right). To balance the on-target efficacy against OT risks, our analyses suggest applying enUn1Cas12f1 when its WT counterpart demonstrates insufficient activities.

We next extended the off-target analyses to a broader list of sites reported by previous studies (on Un1Cas12f1-based editors)27,65,66,67. After transfection, 17 off-target sites corresponding to 6 different sgRNAs were examined via targeted sequencing (Supplementary Fig. 28A). The on/off-target ratios were determined for each site. Compared to WT Un1Cas12f1, enUn1Cas12f1 showed about 1.5-fold (median level) decreases in on/off-target ratios (Supplementary Fig. 28B). Given that the on-target improvements herein by enUn1Cas12f1 over WT Un1Cas12f1 were significant with regard to most of the sgRNAs, these results are relevant to the practical scenario of enUn1Cas12f1 applications. Collectively, our extended OT analyses assigned a modest decrease of targeting fidelity for enUn1Cas12f1 compared to Un1Cas12f1. Future investigations on improving the fidelity of enUn1Cas12f1 and of Cas12f1-derived editors in general are warranted to further strengthen their genetic safety profile.

Following the specificity assessments on enUn1Cas12f1, we next examined the Cas-dependent OT activities by enUn1Cas12f1-derived BEs. We used Cas-OFFinder to predict potential OT sites (with ≤4 mismatches) for two sgRNAs (targeting a RUNX1 site and a VEGFA site featuring editable Cs and Gs, and primarily Gs, respectively). Following transfection of cells with dUn1Cas12f1-evoCDA1, Un1Cas12f1-K473A-evoCDA1 (referred to as WT), Un1Cas12f1-K473A-HMG-evoCDA1 (referred to as HMG-WT), TSminiCBE or HMG-TSminiCBE, the OT sites were subjected to targeted NGS. The two sgRNAs presented high on-target efficiencies with the nickase-based BEs (the latter 4 groups featuring K473A-Un1Cas12f1 or -enUn1Cas12f1, editing levels > 40%, Fig. 6A). Out of 7 or 9 potential off-target targeting sites analyzed for each sgRNA, only 1 site in each group showed increased base edits (with the actual rates remaining low, rates <2%) attributed to the mutations introduced to enUn1Cas12f1 (Fig. 6A). Inclusion of HMG domain was not evidently associated with higher levels of Cas-dependent OT base editing. Although future comprehensive investigations are warranted, the overall rarities of OT editing events by TSminiCBE and HMG-TSminiCBE shown in the current results suggest their generally low Cas-dependent OT activities. Indeed, in comparison to Cas-dependent cleavages, base editing at a potential OT site may be under further restraints such as ssDNA accessibility, sequence context and the availability of editable base(s)38.

A Evaluation of Cas-dependent off-target risk by TSminiCBE and HMG-TSminiCBE. Cas-OFFinder (Cas12f mode) was used to predict potential genomic off-target sites for two sgRNAs. Following TSminiCBE or HMG-TSminiCBE editing, the on-target site and seven potential off-target sites (for each sgRNA) were selected for NGS analyses. TSminiCBE and HMG-TSminiCBE with the non-enhanced counterparts (Un1Cas12f1-473A-BE [WT] and HMG-Un1Cas12f1-473A-BE [HMG-WT]) and dead Un1Cas12f1-evoCDA1 were set as control. The editing activity of C-to-T and G-to-A on the NTS was analyzed for one site (top panel, RUNX1). The G-to-A editing activity on the NTS was analyzed for the other site (bottom panel, VEGFA). All data were obtained from biological replicates (n = 3) and are presented as mean ± SD. B The R-loop assay was used to assess deaminase-dependent off-target activity. The schematic diagram shows the six selected R-loop positions (top panel). The heatmap displays the C-to-T and G-to-A editing levels within the R-loop spacer region, with G bases highlighted in red. The average levels of edits from three biological replicates are also marked in the heatmap. C RNA-seq analysis of SNP numbers in the transcriptome of TSminiCBE- or HMG-TSminiCBE-edited cells. Cells transfected only with the control EGFP plasmid were used as transfection control. The bar plot on the left illustrates the total number of SNPs in each group, while the right panel highlights the number of specific SNP types within each group. Data were obtained from biological replicates (n = 3) and are presented as mean ± SD. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

As BEs may exhibit Cas-independent OT activities at certain genomic locations with exposed single-stranded DNA, it would be important to assess the extent of such off-targeting risk. Therefore, we employed a strategy analogous to the pre-conditioned R-loop approach used in earlier experiment (see Supplementary Fig. 21A), to determine the rate of spurious deaminase targeting at established ssDNA regions. The dUn1Cas12f1 BE, TSminiCBE and HMG-TSminiCBE were programmed to target two genomic sites, in DNMT1 and HNRNPK (Fig. 6B). In the meantime, the nuclease-dead enAsCas12f126 that employed its specific sgRNAs was used to independently induce R-loops either elsewhere in the target genes (4 sites) or within independent genes (2 sites). Like an Un1Cas12f1-based BE, d-enAsCas12f1 could also conceivably expose ssDNA segments in both the NTS and TS. Targeted NGS were performed at these position-fixed, bystanding R-loop sites. Low levels of C-to-T and G-to-A conversions (<5%) could be induced by these editors at some of the R-loop sites, and were likely to be attributed to the actions of unanchored evoCDA1 activities (Fig. 6B). Consistent with this notion, dUn1Cas12f1-evoCDA1 and TSminiCBE showed similar patterns of C/T and G/A off-target modifications at the bystander R-loop sites (Fig. 6B), unlike their clear differences in on-target activity profiles shown earlier (see Fig. 6A). Interestingly, the HMG-TSminiCas12f1 appeared to slightly increase such off-targeting events at certain sites (e.g., sites of DNMT-sg6, HNRNPK-sg4 and HNRNPK-sg6), possibly due to the non-specific DNA binding of the HMG-D module59.

To evaluate potential RNA off-target effects, we performed transcriptome-wide analysis of C-to-U mutations in HEK293T cells transfected with TSminiCBE or HMG-TSminiCBE. Cells transfected with an EGFP plasmid were used as controls. The results indicated that TSminiCBE did not exhibit high RNA off-target activity, which was consistent with previous studies on evoCDA1-containing BEs68,69. Moreover, little RNA off-targeting effects was observed for HMG-TSminiCBE (Fig. 6C). In summary, systematically evaluation of OT activities of TSminiCBE at both genomic and transcriptomic levels demonstrated that TSminiCBE overall presented favorable editing specificity, which further suggested its potential as a highly applicable genome editing tool.

The broadened targetable sites by EnUn1Cas12f1 and HMG-TSminiCBE

Un1Cas12f1 interrogates its targets via first recognizing the TTTR PAM sequence15. However, the relatively low frequency of such 4–nt PAM in the genome (e.g., compared to the NGG PAM for SpCas9) could limit the targeting scope of Un1Cas12f1-derived editors. A previous study of Un1Cas12f1 structure has demonstrated that while A156, Y146 and S142 residues of the REC domain could form various interactions with 5′-TTTR PAM on the NTS side, the Y202 and Q197 of the WED domain could make hydrogen bonds with the first and second A base of the 3′-AAAY complementary motif45. We noted that in enUn1Cas12f1, although such PAM-interacting residues were intact, several nearby residues were substituted into positively charged residues (including D143R, T147R, T203R and Q244R) (Supplementary Fig. 29). Such modifications could enable enUn1Cas12f1 to accommodate broader PAM motifs by serving as an anchor for non-canonical PAM binding, similar to the mechanistic model for the PAM-relaxed SpCas9 variants70. Given that numerous natural Cas12f1 orthologs presented more relaxed requirement for the −4 and −1 positions of the PAM15, we subjected enUn1Cas12f1 and Un1Cas12f1 to comparative tests at potential sites specified by the NTTN motif. To this end, an EGFP reporter system was used. Herein, cleavage at a customizable target site specified by various potential PAM sequences could lead to induction of EGFP fluorescence. As expected, at the TTTR canonical PAMs, enUn1Cas12f1 showed substantially enhanced activities over Un1Cas12f1 (Supplementary Fig. 30A). Importantly, enUn1Cas12f1 demonstrated a more expanded PAM recognition range than Un1Cas12f1, and recognized targets specified by the −4 position-relaxed NTTR PAM, along with the −1 position-relaxed TTTN PAM (Supplementary Fig. 30A, B).

To validate the results from the reporter experiment, we next designed sgRNA sequences to target various genomic sites preceded by the non-canonical ATTG, CTTG, and GTTG PAMs. The HEK293T cells were subjected to editing with these targeting sgRNAs in combination with Un1Cas12f1, enUn1Cas12f1, or a positive control, i.e., enAsCas12f, which naturally recognizes the NTTR PAM sequence15. The results revealed that enUn1Cas12f1 not only outperformed Un1Cas12f1 for all three new PAM sequences, but also exhibited overall equivalent activities as enAsCas12f (Supplementary Fig. 30C, D). Therefore, an additional advantage of our engineered enUn1Cas12f1 variant over Un1Cas12f1 is manifested by its more relaxed PAM requirement and significantly broadened targeting scope.

We also subjected our latest version of enCas12f1-derived BE, i.e., HMG-TSminiCBE, to tests at target sites specified by the new PAM motifs (NTTR). To this end, we selected eight target sites preceded by CTTR, ATTR or GTTR, and assessed HMG-TSminiCBE editing at these sites. NGS analysis revealed that HMG-TSminiCBE achieved efficient NTS G-to-A editing across these loci (Supplementary Fig. 30E). Overall, the above findings demonstrated the application potential of enUn1Cas12f1 and HMG-TSminiCBE to target a much broader space in the genome.

Discussion

Cas12f-derived BEs present a valuable class of compact, precise editing tools with strong in vivo application potential. Despite some recent efforts, there is still considerable need for the construction of more potent Cas12f-BEs, and for the improvement of their versatility for various application contexts. Here, we aimed to first independently screen for enhanced Un1Cas12f1 variants (Figs. 1, 2, and Supplementary Fig. 31A for summary). Computational prediction of saturation point mutations for enhanced Un1Cas12f1/sgRNA/DNA complex stabilities allowed the initial selection of 31 residues for further testing. For these positions, we carried out a round of pooled screen with two groups of degenerate codons covering all amino acid substitutions at individual positions. The pooled screen with a reporter for cleavage activities led to rapid identification of 17 candidate positions whose alterations generally led to increases in Un1Cas12f1 cleavage activities (Fig. 1C). Next, all amino acid mutations at each of the 17 positions were individually tested on the reporter system, which resulted in establishment of more than 40 point mutations with potential enhancement effects (Supplementary Fig. 3). Another round of computational prediction on double or triple combinational mutations for eight beneficial point substitutions was performed to assign 14 promising double/triple mutations. Further testing of these double/triple mutations, followed by screening of additional combination mutations, led to identification of three most-improved Un1Cas12f1 variants (v1.1 ~ 1.3) (Fig. 2, and Supplementary Fig. 31A for summary). We combined mutations from one of top variant with two previously established enhancing substitutions (related to miniCRa19) to establish the enUn1Cas12f1 (Supplementary Fig. 4). Importantly, the enUn1Cas12f1 significantly out-performed two previously engineered Un1Cas12f1 variants (the miniCRa and CasMINI nucleases16,19,52) to drive robust cleavage at a panel of genomic locations, which demonstrated the effectiveness of our earlier improvement efforts (Supplementary Fig. 4). In further benchmarking experiments, enUn1Cas12f1 showed superior performance compared to enAsCas12f and comparable to SpCas9 (Supplementary Figs. 6, 7). Importantly, in a mouse model to test the in vivo efficacy of AAV-delivered Cas12f to target a disease gene (i.e., Ttr), the enUn1Cas12f vector demonstrated robust editing rates in the liver and significantly reduced plasma TTR levels, in contrast to the minimal effect by Un1Cas12f1 vector (Fig. 3). Hence, our computational prediction-aided screening strategy enabled rapid establishment of a strongly enhanced Un1Cas12f1 variant that could be readily adopted to cleavage-dependent in vivo applications, and could also be further adapted for downstream development of BEs.

When the prototype nuclease-dead Un1Cas12f1 and enUn1Cas12f1 was adapted to BEs, we found that an engineered evoCDA1 deaminase was the most compatible deaminase module (Fig. 4A). This was consistent with a previous report where evoCDA1 exhibited optimal C-to-T editing efficiency on the NTS when paired with Cas12a71. It was also possible that evoCDA1’s ssDNA-binding region might also contribute to its favored compatibility with dUn1Cas12f72. Importantly, enUn1Cas12f1-evoCDA1 drove much improved C-to-T editing than the Un1Cas12f1-derived BE (Supplementary Fig. 10), which confirmed the productiveness our Cas12f protein-centered strategy toward development of high-activity BEs. Quite intriguingly, dUn1Cas12f1-evoCDA1 editing was associated with visible levels of G-to-A edits in the PAM-distal portion of the target site, a product type that were indeed installed more effectively by d-enUn1Cas12f1-evoCDA1 (Fig. 4A–C and Supplementary Figs. 10, 11). These results highlighted a TS-editing activity by Cas12f1-CBE to also target certain C bases in the TS strand. To our knowledge, this represents a previously unreported capability of CRISPR/Cas-BE. Such an unexpected activity could provide Cas12f1-BEs with a much-expanded targeting scope than the conventional standard, and assigned strong versatility to this BE class. It was worth noting that careful examination of Cas12a-evoCDA1 products also revealed certain levels of G-to-A edits (Supplementary Fig. 12). Based on these observations, we put forward a model where a characteristic stage associated with Cas12 family targeting, i.e., conformational rearrangement to expose a ssDNA segment in the TS44,48, plays an essential role in licensing direct TS targeting by the deaminase (Fig. 4E). Therefore, the structural determinants associated with the employment of a single RuvC domain in Cas12 family protein15 to access both the NTS and TS might have shaped the flexibility of Cas12-BE to target cytosines on both strands. The fact that free rAPOBEC1 or evoCDA1 could induce detectable G-to-A edits (in addition to C-to-T edits) at parallelly d-enUn1Cas12f1-targeted sites provided further evidence for such non-canonical occurrence of ssDNA conformation at the TS (Supplementary Fig. 21).