Introduction

Nowadays, due to the harms such as increasing the possibility of heart and carcinogenic risks and the occurrence of digestive problems that synthetic food additives have for the body, using natural preservatives is an important approach for extending the shelf life of food1. Chemical preservatives are frequently utilized in the food industry due to their simple process and affordable cost. However, problems have been caused due to the inadequate utilization of chemical preservatives2.

Natural preservatives have been described as potential alternatives to chemical preservatives due to their antioxidant or antibacterial properties3. There is an increasing attention on antimicrobial compounds derived from plants and animals that can efficiently control microbiological and chemical spoilage, hence improving the shelf life of food4. So far, many synthetic antioxidants have been used in the food industry, including antioxidants such as BHA and BHT, which have strong antioxidative properties5. However, the interest of consumers to use natural products has increased the attention of the food industry toward the use of natural antioxidants in order to extend the shelf life or enhance the safety of food6.

Bioactive peptides and protein hydrolysates derived from food have antimicrobial and antioxidant activity. As bioactive food additives extend the shelf life of food products, they have gained significant attention in the food industry3. Enzymatic hydrolysis and fermentation are used to produce peptides from proteins. Bacillus species can produce significant amounts of non-specific proteolytic enzymes and have high growth potential in harsh environments with limited and inexpensive carbon and nitrogen sources. Therefore, the fermentation process is more cost-effective than hydrolysis by commercial enzymes7. Bacillus strains, including B. licheniformis8, B. subtilis9, B. altitudinis HK0210, and B. mojavensis A2111 were used as fermenting bacteria that are highly efficient in protein hydrolysis to produce bioactive peptides. Bioactive peptides can be produced from various plant and animal sources. Plants are a rich source of proteins with high nutritional value. In recent studies, agricultural and industrial waste proteins have been used to produce peptides with bioactive properties12. Sesame (Sesamum indicum L.) is a significant oilseed plant with global importance, commonly used for various purposes. It is an important source of nutrients and energy. It is reported that sesame seeds contain 50–60% oil and 25% protein13. Sesame meal is a protein-rich by-product obtained after extracting oil from sesame seed, containing roughly 50% protein, which is used as a high-protein food source for livestock and poultry14. The researchers reported that the peptide obtained from the enzymatic hydrolysis of sesame protein by alcalase and trypsin had an antioxidant effect; these researchers identified seven peptides, determined their sequence, and demonstrated that it has the highest antioxidant activity, and it can be used as functional foods15.

The purpose of this research was to optimize the fermentation conditions containing time, temperature, and protein concentration for the preparation of sesame meal protein hydrolysate by B. coagulans and to investigate the antimicrobial activity against pathogenic bacteria and antioxidant properties, including DPPH radical inhibition and ferric ion reducing power. Chemical composition, amino acid profiles, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, and the effect of different concentrations of optimal samples on antioxidant activity were evaluated.

Materials and methods

Materials

Sesame meal was purchased from the Keshavarz Food Industry CO (Qom, Iran). 2, 2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) and o-phthaldialdehyde (OPA) were prepared from Sigma Aldrich (Darmstadt, Germany).

Microbial strains

B. coagulans IBRC 10,807, E. coli PTCC1399, C. perfringens PTCC 1765, L. monocytogenes PTCC 1298, S. aureus PTCC 29,213.

Preparation of Sesame meal protein isolate

At first, sesame meal was ground, then defatted using hexane (1:5 w/v) and was agitated at ambient temperature for 3 h. Hexane was removed using a Buchner funnel, then dried in an air-drying oven at 30 °C and passed through a 40-mesh sieve. The defatted sesame meal powder was blended with deionized water (1:10 ratio w/v), and the pH value was increased to 11 using 1 N NaOH, and the mixture was agitated continuously for 1 h at 50 °C. It was centrifuged (Combi-514R, South Korea) at 6000 rpm for 20 min to remove the insoluble fraction. Next, the pH of the supernatant was altered to 4.2 (isoelectric pH) with 1 N HCl and stirred (Labtron, Iran) for 30 min. The precipitate obtained was centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 20 min, and the protein isolate was kept for further experiments15.

Chemical composition

The chemical composition of raw sesame meal, defatting, and protein isolate containing moisture, protein content, fat, and ash content were estimated by the American Association of Cereal Chemists16.

Amino acid composition (by HPLC)

Analysis of amino acids was performed by HPLC (Young Lin Korea) and Teknokroma RP-C18 ODS-A column (15 cm × 0.46 cm, 5 μm), flow rate (1.3 mL/min) and temperature of 35 °C, using the method of Jiang et al.17. Sesame protein was hydrolyzed by 6 N HCl at 110 °C for 24 h. The amino acid contents were stated as g/100 g of the total amount of amino acids.

Peptide concentration

Peptide concentration of sesame protein hydrolysate was evaluated based on the reaction of the amino groups using the o-phthalaldehyde (OPA) reagent. 2.5 mL of the supernatant and 5 mL of 10% TCA were mixed, and after 10 min, it was shaken for 10 min at 5000 rpm. The supernatant obtained was used to evaluate proteolysis. 3 mL of prepared OPA reagent was combined with 200 µL of supernatant, and after 2 min, the absorbance was obtained at 340 nm. A standard curve of different concentrations of L-serine amino acid (0.002-0.5 mg/mL) was prepared for calculating protease activity18.

Optimization of fermentation

Response surface methodology (RSM) was determined to optimize the temperature, time, and substrate concentration. The central composition design was used with three independent variables: time, temperature, and substrate concentration. The levels of temperature, time, and substrate concentration (SPI) are given in Table 1. 0.03% MgSO4, 0.1% K2HPO4, 1% glucose, 0.05% CaCl2 w/v, and 2% v/v of the inoculum were added to the culture medium. The supernatant obtained after fermentation was filtered with a 0.45 μm filter, then the pH was increased to 7. The supernatants were freeze-dried (FDB 5503, South Korea) and stored at -20 °C. Antimicrobial and antioxidant tests (DPPH radical scavenging and reducing power) were performed as a response variable19.

Antimicrobial activity

The antimicrobial activity of SPH was done based on the method of Aguilar-Toalá et al.20. E. coli, S. aureus, L. monocytogenes, and C. perfringens were used to analyze antimicrobial activity. 20 mg of SPH was dissolved in 900 µL of Mueller Hinton Broth culture medium, and 100 µL of bacteria with a concentration of 105 cfu/mL was mixed and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 600 nm. Muller Hinton broth culture medium containing bacterial suspension (105 cfu/mL) was used as a positive control.

Antioxidant activities

DPPH radical inhibition

DPPH radical scavenging activity of sesame protein hydrolysate was evaluated using the method defined by Jemil et al.21. 500 µL of SPH was combined with 375 µL of ethanol. Afterwards, 125 µL of 0.15 mM DPPH (prepared in absolute ethanol) was added to the sample and left in the dark for 30 min. The absorbance of the samples was performed at 517 nm. Distilled water was used instead of the SPH in the negative control. The percentage of inhibition was determined by the following equation:

DPPH radical scavenging: (::frac{text{A}-text{B}}{text{B}}times:100)%. A represents the absorbance value of the control, B represents the absorbance value of the solution.

Reducing power

The reducing power of the SPH was performed by the method of Bougatef et al.22. 500 µL of SPH with phosphate buffer and 500 µL of potassium ferricyanide were combined and incubated at 50 °C for 30 min. Afterward, 10% TCA was applied to the solution. Then, the mixture was shaken at 12,000 rpm for 10 min. The obtained supernatant was mixed with 0.1% w/v ferric chloride. The absorbance of the mixture was determined at a wavelength of 700 nm after 10 min.

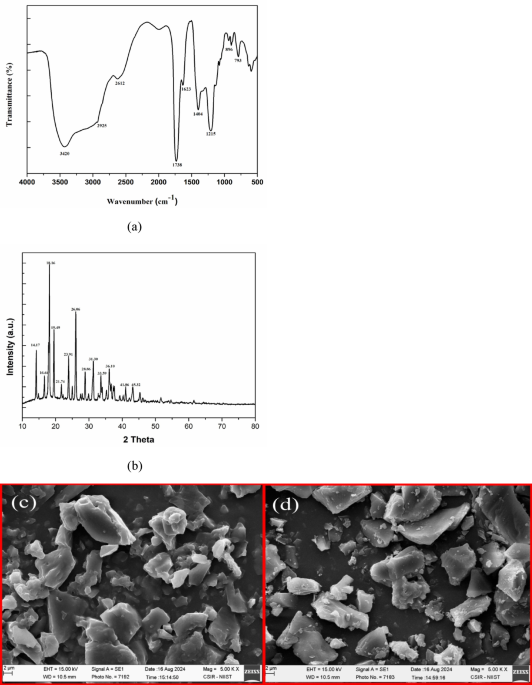

Scanning electron microscopy

SEM was conducted using a scanning electron microscopy (Tescan, Czech Republic). Sputtering was used to apply a thin layer of gold to the samples. The images were observed at a working distance of 4.95 mm and an accelerating voltage of 15 kV23.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (Perkin Elmer, Spectrum RX1) of SPI and SPH was examined in the wavelength range of 400–4000 cm− 1 with a resolution of 4 cm− 1. Sample preparation for analysis was accomplished by mixing the sample and potassium bromide (KBr) powder24.

Statistical analysis

In this research, the response surface methodology (RSM), based on the central-composite design, was used to determine optimal levels of the independent variable. The statistical data analysis was executed using the Stat-Ease Design Expert software version 11. SPSS 26 statistical software was utilized to analyze the chemical composition, protease activity, and antioxidant activity. The Duncan’s test was conducted to compare the means at the significance level of 5%.

Results and discussion

Chemical composition

The range of moisture, protein, fat, and ash of raw meal, defatted sesame, and protein isolate is given in Table 2. According to the results obtained, the fat content of raw sesame meal is reduced from 16% to 2.33% in protein isolate. The final reduction of fat in protein isolate was due to using hexane solvent, protein extraction in an alkaline solution, and protein precipitation at the isoelectric point25. The lowest amount of ash was related to protein isolate due to the removal of large amounts of non-protein compounds in the protein extraction process. The protein content of raw and defatted sesame meal was 27.3% and 42.63%, respectively, indicating that sesame meal is a rich source of protein that can be used as a protein-rich substrate26.

Sesame amino acid profile

The functional and physicochemical properties of sesame protein and its use as a food supplement for nutritional applications have been reported by Achouri et al.25. According to Table 3; Fig. 1, the total amount of amino acids was 92.31 g/100 g. Glutamic acid 18.26, arginine 12.39, and aspartic acid 9.34 g/100 g had the highest amounts27. Among them, some of the essential amino acids have been reported, including phenylalanine 4.93, arginine 12.39, valine 6.19, lysine 1.82, leucine 7.98, isoleucine 4.66, histidine 2.13, threonine 3.14 and methionine 1.72 g/100 g; consequently, 44.96 g of the total amount of amino acids were related to these amino acids. Onsaard28 reported that sesame protein isolate has high amounts of the amino acids arginine, glutamic acid, leucine, and valine, which can be used as a dietary supplement. The difference in the amount of amino acids can be attributed to genetic differences between sesame varieties29. Hydrophobic amino acids, including phenylalanine, proline, methionine, alanine, leucine, isoleucine, tyrosine, and lysine, which are reported in Table 3, are responsible for the bioactive properties of protein hydrolysate. Hydrophobic amino acids with antioxidant properties bind to free radicals, consequently limiting their availability to the target cell30. Amino acids such as tryptophan, tyrosine, cysteine, methionine, lysine, histidine, and arginine play an important role in the antimicrobial properties of protein hydrolysate. The binding of antimicrobial protein hydrolysate to the cell membrane causes disruption of membrane integrity, depolarization, and osmotic imbalance, ultimately leading to cell death31. The findings demonstrate that sesame meal can be used as a suitable protein source for producing protein hydrolysates with bioactive properties.

Peptide concentration

Evaluating proteolysis activity is a crucial parameter to examine the release of peptides in the fermentation process. In addition, the peptide concentration was evaluated using the OPA method. This method’s basis was measuring the free amino group produced during the fermentation process. The results in Fig. 2 demonstrated that the progress of fermented hydrolysis of protein during 0, 12, 24, 36, and 48 h after fermentation for this strain was significant (p < 0.05). The hydrolysis process showed that B. coagulans has used SPI as a carbon and nitrogen source and has obtained its nutritional needs. The peptide concentration exhibited a rapid increase after 12 h of fermentation, and this process persisted until 48 h. The highest peptide concentration was found at 36 h after fermentation. Some peptides were observed in the culture medium before fermentation, probably released during sterilization32. With the increase in time up to 36 h, the content of amino acids and peptides increased continuously, and then at 48 h, no significant increase was observed (p > 0.05). Li & Wang reported that during fermentation of chickpeas by B. subtilis lwo, increasing protease activity led to an increased release of peptides and free amino nitrogen, which attained their highest values33. Proteolysis of cereal protein and plant seeds by Bacillus species has been reported. Zhu et al.34 reported that B. subtilis showed the highest protease activity after 24 h of fermentation in the presence of soybean substrate. According to the findings of Shi et al.35 soybean and corn meal fermented by B. subtilis were hydrolyzed to peptides less than 25 kDa.

Analysis of the amino acid and peptide concentrations of hydrolysates at different time intervals. Data values were performed in triplicate (Mean ± SD).

Optimization of fermentation conditions

In this research, independent variables included substrate concentration, temperature, time, and the effect of these factors on dependent variables, including DPPH radical inhibition, ferric ion reducing power, and the antimicrobial properties of hydrolysate against E. coli, S. aureus, C. perfringens, and L. monocytogenes were evaluated. The results are given in Table 4. The highest DPPH radical inhibition and reducing power levels were 83.7% and 0.799% (absorbance at 700 nm), respectively. A polynomial regression model with the quartic term (Eqs. 1, 2) was used to analyze DPPH radical scavenging and reducing power. According to the results of the analysis of variance in Table 5; Fig. 3, the effect of temperature, time, and A2 and B2 variables on DPPH radical inhibition and the effect of time, substrate concentration, and A2, B2, and C2 variables on reducing power were significant (p < 0.05). The regression model with R2 of 0.8106 and R2 of 0.8649 was proposed for DPPH radical scavenging and reducing power, respectively. Therefore, the model could explain 81.06% and 86.49% of the total variations in the investigated variables.

Contour plots demonstrating the effects of independent parameters (temperature, time, and SPH concentrations) on antibacterial and antioxidant activities.

(1) DPPH radical scavenging = + 70.5056–7.30098 A + 12.3746B + 2.06483 C-3.7625AB-2.6875AC + 1.1375BC-10.0212A2-8.60701B2-2.70267C2.

(2) Reducing power = 0.762378–0.0268893 A + 0.0765043B + 0.063587 C-0.0105AB-0.00325AC + 0.024BC -0.139705A2 -0.106648B2 -0.0753583C2.

According to the obtained results (Table 4; Fig. 3), the effect of time and substrate concentration on the reducing power of the hydrolysate was significant (p < 0.05), and the reducing power increased with increasing time, which caused more hydrolysis and production of peptides with high electron-donating ability. The high concentration of the substrate (optimal concentration) caused an increase in the reducing power. However, in concentrations higher than the optimal value, no significant increase was observed (p > 0.05) because the high concentration of the substrate may inhibit the production of the protease enzyme, which was consistent with the research of Fakhfakh et al.36. In relation to DPPH radical inhibition, increasing the temperature and time (Fig. 3) to the optimal value led to hydrolysate production with the highest inhibitory effect, which converted free radicals into stable compounds. Increasing the temperature more than the optimal level caused a decrease in enzyme activity. Huang et al.37 stated that fermentation temperature plays an important role in determining antioxidant activity. With hydrolysis over a more extended time, peptides may be hydrolyzed or consumed by bacteria as an energy source.

Regarding the antimicrobial activity, the highest inhibition against S. aureus, E. coli, L. monocytogenes, and C. perfringens was obtained at 78%, 62.7%, 85%, and 87.7%, respectively. According to the analysis of variance mentioned in Table 5, the effect of time, temperature, and variables A2 and B2 on the inhibition of S. aureus was significant (p < 0.05), among which A2 had a more significant effect. R2 of 0.9091 for this quadratic model (Eq. 3) showed the excellent ability of the proposed model to predict independent variables on the inhibition of S. aureus. A polynomial equation (quadratic model) was proposed for the inhibition of E. coli (Eq. 4). The coefficient of determination (R2) of 0.8643 showed that the model could explain 86% of the variations in the inhibitory effect of SPH against E. coli. According to the p-value of the quadratic model terms (Eq. 5) and R2 of 0.8792, time, temperature, and variables A2, B2, and C2 had statistically significant effects on the inhibitory effect of SPH against L. monocytogenes. Due to the analysis of variance results, R2 of 0.8928 demonstrated that the proposed model can well explain the effect of independent variables against C. perfringens.

(3) S. aureus inhibition = + 69.2652–11.1951 A + 15.1311B + 4.29781 C-8.15AB-2.35AC + 0.025BC-17.3741A2-11.9647B2-5.83057C2.

(4) E. coli inhibition = + 59.3089–8.09879 A + 10.615B + 4.78142 C-6.4AB-1.425AC-16.1956A2-10.6625B2-5.99557C2.

(5) L. monocytogenes inhibition = + 78.2311–10.418 A + 14.9587B + 5.47436 C-6.225AB-0.8AC-0.25BC-22.3774A2-14.0866B2-9.84396C2.

(6) C. perfringens inhibition = + 78.3746–7.51767 A + 15.3561B + 8.51145 C-4.462AB-3.3375AC-1.1625BC-18.9232A2-14.4508B2-8.67019 C.

According to the obtained results, the SPH had an antimicrobial effect. Independent variables significantly affected the antimicrobial activity of hydrolysate (Fig. 3). By increasing the time and determining the optimal temperature for the growth of B. coagulans and enzyme activity, the degree of hydrolysis increased. Antimicrobial peptides typically consist of less than 50 amino acids, approximately half of which are hydrophobic38. In addition, these peptides had a low molecular weight, usually less than 10 kDa39. The antimicrobial activity of peptides was very different depending on the type of amino acid, structure, length of peptides, and their sequence40. Amino acids such as tryptophan and arginine play an essential role in determining the antimicrobial properties of peptides41.

In the model validation, the optimal conditions suggested by the software were temperature 34.93 °C, time 31.34 h, and substrate concentration 4.92%. Under these conditions, DPPH radical inhibition and reducing power were 77.75% and 0.784, respectively. The inhibitory effect of SPH against S. aureus, E. coli, L. monocytogenes, and C. perfringens was 77.59%, 65.93%, 84.38%, and 85.69%, respectively. In the optimal conditions mentioned by the model, fermentation was carried out, and DPPH radical inhibition and iron ion reducing power were obtained, 79.26% and 0.758 (absorbance at 700 nm), respectively. The inhibitions of S. aureus, E. coli, L. monocytogenes, and C. perfringens were 78.28%, 63.68%, 80.43%, and 87.34%, respectively. These results showed the model’s ability to investigate the effect of independent variables on sesame protein hydrolysate’s antioxidant and antimicrobial activity.

Antioxidant activity of the optimal treatment in different concentrations

Reducing power

The reducing power is the ability of the protein hydrolysate to donate electrons. The absorbance at 700 nm shows the high reducing power of the antioxidant composition. As represented in Fig. 4, increasing the hydrolysate concentration increased the reducing power significantly (p < 0.05). All samples had lower reducing power than vitamin C, but the concentration of 50 mg/mL exhibited the highest reducing power compared to lower concentrations. Our results were consistent with those of Zhang et al.42. who investigated peanut protein hydrolysis by Bacillus subtilis and reported that the reducing power increased significantly with increasing concentration, which could be due to the production of low molecular weight bioactive peptides containing antioxidant amino acids. It was stated that the increase in the reducing power of the protein hydrolysate could be due to the increased production of electron-donating peptides43. Furthermore, the reducing power depends on the type of amino acids, such as tryptophan, tyrosine, methionine, histidine, and lysine, in the peptide chain and their sequence. On the other hand, protease activity during fermentation has an important role in determining the antioxidant properties of the peptide44.

Ferric ion reducing power of the hydrolysate at different concentrations. Data values were performed in triplicate (Mean ± SD).

DPPH radical inhibition

DPPH radical inhibition was used to evaluate the antioxidative potential of SPH at different concentrations, which had the highest absorbance at the wavelength of 517 nm. The results are shown in Fig. 5, DPPH radical inhibition activity increased with increasing concentration. Among different concentrations, the concentration of 50 mg/mL of hydrolysate showed the highest percentage of radical inhibition, which had a higher inhibitory activity compared to vitamin C. Our findings were in agreement with the research reported by Jemil et al.21 who stated that DPPH radical scavenging activity increased with increasing protein hydrolysate concentration. Therefore, the DPPH radical scavenging activity of hydrolysate obtained from fermentation by Bacillus subtilis was dose-dependent. Abd Rashid et al.45 reported that the higher DPPH radical inhibition ability of the fish protein hydrolysate in different concentrations depends on the type of protein substrate used in the fermentation process and the mechanism of action of proteolytic enzymes produced by different strains to produce peptides with different sizes. Zhi et al.8 reported that antioxidant activity depends on the amount and position of aromatic, acidic, and basic amino acids.

DPPH radical inhibition of the hydrolysates at different concentrations. Data values were performed in triplicate (Mean ± SD).

Scanning electron microscopy

Electron microscopy was performed to evaluate the microstructure of the protein and hydrolysate. According to Fig. 6, it was observed that the protein consists of heterogeneous, compact, and organized spherical particles46. The protein hydrolysate has formed smaller particles, indicating that the fermentation was able to hydrolyze the protein into a lower molecular weight peptide. The difference in morphological characteristics between protein isolate and protein hydrolysate can be attributed to the enzymatic hydrolysis of protein by proteases produced during the fermentation process, which has led to the breakdown of the protein molecular skeleton23.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) of sesame meal protein isolate (a), and sesame meal protein hydrolysate (b).

FTIR spectroscopy

The FTIR spectra of SPI and SPH (hydrolysis with B. coagulans) are given in Fig. 7. Sesame protein isolate (SPI) and sesame protein hydrolysate (SPH) showed some peaks in the regions 3394–3401, 2900, 1654, 1541–1560, and 1400–1457 cm− 1, which were correlated to amides A, B, amides I, II, and III respectively. Amide A showed O-H stretching and N-H stretching with hydrogen bonding. Stretching vibrations of the C = O groups or C = C in alkenes were related to amide I. Amide II showed C-N stretching vibration or N-H bending. The peak that appeared at 2900 cm− 1 was related to the C-H vibration of alkane47,48. According to the formation of different peaks and the creation of different functional groups, it can be concluded that B. coagulans has caused protein hydrolysis by producing protease.

Conclusion

In this study, sesame protein, after extraction, was used to produce fermented hydrolysate by B. coagulans. According to the results, fermentation hydrolysis depends on factors such as fermentation temperature, time, type, and substrate concentration. Sesame seeds are a potential source of protein. Amino acid composition is an important parameter in the bioactivity properties of fermented peptides. All essential amino acids for sesame protein were recorded by HPLC. The results showed that B. coagulans had high proteolytic activity that caused the hydrolysis of sesame protein and produced hydrolysates with high antioxidant and antimicrobial capabilities. Based on the findings of this research, sesame meal protein hydrolysate can replace chemical preservatives and minimize their harmful effects.

Data availability

The datasets generated during this study are available from the corresponding author upon request (email: [khomeiri@gau.ac.ir]).

References

-

Salaheen, S., Peng, M. & Biswas, D. Replacement of conventional antimicrobials and preservatives in food production to improve consumer safety and enhance health benefits. Microbial Food Saf. Preserv. Tech. 311–314 (2015).

-

Zhang, S., Luo, L., Sun, X. & Ma, A. Bioactive peptides: a promising alternative to chemical preservatives for food preservation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 69, 12369–12384 (2021).

-

Tkaczewska, J. Peptides and protein hydrolysates as food preservatives and bioactive components of edible films and coatings-A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 106, 298–311 (2020).

-

Bouarab Chibane, L., Degraeve, P., Ferhout, H., Bouajila, J. & Oulahal, N. Plant antimicrobial polyphenols as potential natural food preservatives. J. Sci. Food Agric. 99, 1457–1474 (2019).

-

Xu, X. et al. Synthetic phenolic antioxidants: Metabolism, hazards and mechanism of action. Food Chem. 353, 129488 (2021).

-

Lorenzo, J. M. et al. Bioactive peptides as natural antioxidants in food products–A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 79, 136–147 (2018).

-

Contesini, F. J., Melo, R. R. D. & Sato, H. H. An overview of Bacillus proteases: from production to application. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 38, 321–334 (2018).

-

Zhi, T. et al. Novel antioxidant peptides from protein hydrolysates of scallop (Argopecten irradians) mantle using enzymatic and microbial methods: Preparation, purification, identification and characterization. LWT – Food Sci. Technol. 164, 113636 (2022).

-

Jemil, I. et al. Novel bioactive peptides from enzymatic hydrolysate of sardinelle (Sardinella aurita) muscle proteins hydrolysed by Bacillus subtilis A26 proteases. Food Res. Int. 100, 121–133 (2017).

-

Hwang, C. F., Chen, Y. A., Luo, C. & Chiang, W. D. Antioxidant and antibacterial activities of peptide fractions from flaxseed protein hydrolysed by protease from Bacillus altitudinis HK02. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 51, 681–689 (2016).

-

Jemil, I. et al. Peptidomic analysis of bioactive peptides in zebra blenny (Salaria basilisca) muscle protein hydrolysate exhibiting antimicrobial activity obtained by fermentation with Bacillus mojavensis A21. Process. Biochem. 51, 2186–2197 (2016).

-

Montserrat-de la Paz, S. et al. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of bioavailable protein hydrolysates from lupin-derived agri-waste. Biomol 11, 1458 (2021).

-

El Khier, M. K. S., Ishag, K. E. A. & Yagoub, A. A. Chemical composition and oil characteristics of Sesame seed cultivars grown in Sudan. Res. J. Agric. Sci. 4, 761–766 (2008).

-

Chatterjee, R., Dey, T. K., Ghosh, M. & Dhar, P. Enzymatic modification of Sesame seed protein, sourced from waste resource for nutraceutical application. Food Bioprod. Process. 94, 70–78 (2015).

-

Lu, X., Zhang, L., Sun, Q., Song, G. & Huang, J. Extraction, identification and structure-activity relationship of antioxidant peptides from sesame (Sesamum indicum L.) protein hydrolysate. Food Res. Int. 116, 707–716 (2019).

-

American Association of Cereal Chemists. Approved Methods Committee, Approved Methods of the American Association of Cereal Chemists (AACC, 2000).

-

Jiang, L., Wang, B., Li, B., Wang, C. & Luo, Y. Preparation and identification of peptides and their zinc complexes with antimicrobial activities from silver carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix) protein hydrolysates. Food Res. Int. 64, 91–98 (2014).

-

Bah, C. S., Carne, A., McConnell, M. A., Mros, S. & Bekhit, A. E. D. A. Production of bioactive peptide hydrolysates from deer, sheep, pig and cattle red blood cell fractions using plant and fungal protease preparations. Food Chem. 202, 458–466 (2016).

-

Tavallaie, S., Khomeiri, M., Mousivand, M., Maghsoudlou, Y. & Hashemi, M. Starches from different sources hydrolysis using a new thermo-tolerant amylase complex produced by Bacillus subtilis T41a: characterization and efficiency evaluation. LWT – Food Sci. Technol. 112, 108218 (2019).

-

Aguilar-Toalá, J. E. et al. Assessment of multifunctional activity of bioactive peptides derived from fermented milk by specific Lactobacillus plantarum strains. J. dairy. sci. 100, 65–75 (2017).

-

Jemil, I. et al. Functional antioxidant and antibacterial properties of protein hydrolysates prepared from fish meat fermented by Bacillus subtilis A26. Process. Biochem. 49, 963–972 (2014).

-

Bougatef, A. et al. Purification and identification of novel antioxidant peptides from enzymatic hydrolysates of sardinelle (Sardinella aurita) by-products proteins. Food Chem. 118, 59–565 (2010).

-

Chen, G. et al. Preparation, characterization and the in vitro bile salts binding capacity of celery seed protein hydrolysates via the fermentation using B. subtilis. LWT – Food Sci. Technol. 117, 108571 (2020).

-

Raei, P., Khomeiri, M., Mahounak, A. S., Moayedi, A. & Kashiri, M. Characterization of bacterial Cellulose/PVA composite films incorporated with Sesame meal protein hydrolysate: Physicochemical, Antimicrobial, and antioxidant properties. Appl. Food Res. 100727 (2025).

-

Achouri, A., Nail, V. & Boye, J. I. Sesame protein isolate: Fractionation, secondary structure and functional properties. Food Res. Int. 46, 360–369 (2012).

-

Yamauchi, K., Samanya, M., Seki, K., Ijiri, N. & Thongwittaya, N. Influence of dietary Sesame meal level on histological alterations of the intestinal mucosa and growth performance of chickens. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 15, 266–273 (2006).

-

Makinde, F. M. & Akinoso, R. Comparison between the nutritional quality of flour obtained from raw, roasted and fermented sesame (Sesamum indicum L.) seed grown in Nigeria. Acta Sci. Pol. Technol. Aliment. 13, 309–319 (2014).

-

Onsaard, E. Sesame proteins. Int Food Res J. 19, 1287–1295 (2012).

-

Nweke, F. N., Ubi, B. E. & Kunert, K. J. Determination of proximate composition and amino acid profile of Nigerian Sesame (Sesamum indicum L.) cultivars. Niger J. Biotechnol. 23 (2011).

-

Cruz-Casas, D. E. et al. Bioactive protein hydrolysates obtained from Amaranth by fermentation with lactic acid bacteria and Bacillus species. Heliyon 9 (2023).

-

Datta, S. & Roy, A. Antimicrobial peptides as potential therapeutic agents: a review. Int J Pept Res Ther. 27, 555–577 (2021).

-

Moayedi, A., Hashemi, M. & Safari, M. Valorization of tomato waste proteins through production of antioxidant and antibacterial hydrolysates by proteolytic Bacillus subtilis: optimization of fermentation conditions. J Food Sci Technol. 53, 391–400 (2016).

-

Li, W. & Wang, T. Effect of solid-state fermentation with Bacillus subtilis Lwo on the proteolysis and the antioxidative properties of Chickpeas. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 338, 108988 (2021).

-

Zhu, Y. P., Fan, J. F., Cheng, Y. Q. & Li, L. T. Improvement of the antioxidant activity of Chinese traditional fermented Okara (Meitauza) using Bacillus subtilis B2. Food Control. 19, 654–666 (2008).

-

Shi, C., Zhang, Y., Lu, Z. & Wang, Y. Solid-state fermentation of corn-soybean meal mixed feed with Bacillus subtilis and Enterococcus faecium for degrading antinutritional factors and enhancing nutritional value. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 8, 1–9 (2017).

-

Fakhfakh, N. et al. Total solubilisation of the chicken feathers by fermentation with a keratinolytic bacterium, Bacillus pumilus A1, and the production of protein hydrolysate with high antioxidative activity. Process. Biochem. 46, 1731–1737 (2011).

-

Huang, Y. H., Lai, Y. J. & Chou, C. C. Fermentation temperature affects the antioxidant activity of the enzyme-ripened sufu, an Oriental traditional fermented product of soybean. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 112, 49–53 (2011).

-

Shen, W. et al. From antimicrobial peptides to antimicrobial Poly (α-amino acid) s. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 7, 1800354 (2018).

-

Zhu, X. et al. Characterization of antimicrobial activity and mechanisms of low amphipathic peptides with different α-helical propensity. Acta Biomater. 18, 155–167 (2015).

-

Pane, K. et al. Antimicrobial potency of cationic antimicrobial peptides can be predicted from their amino acid composition: application to the detection of cryptic antimicrobial peptides. J. Theor. Biol. 419, 254–265 (2017).

-

Jeżowska-Bojczuk, M. & Stokowa-Sołtys, K. Peptides having antimicrobial activity and their complexes with transition metal ions. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 143, 997–1009 (2018).

-

Zhang, Y. et al. Isolation and identification of an antioxidant peptide prepared from fermented peanut meal using Bacillus subtilis fermentation. Int. J Food Prop. 17, 1237–1253 (2014).

-

Callegaro, K., Welter, N. & Daroit, D. J. Feathers as bioresource: microbial conversion into bioactive protein hydrolysates. Process. Biochem. 75, 1–9 (2018).

-

Zhu, K., Zhou, H. & Qian, H. Antioxidant and free radical-scavenging activities of wheat germ protein hydrolysates (WGPH) prepared with alcalase. Process. Biochem. 41, 1296–1302 (2006).

-

Abd Rashid, N. Y. et al. Evaluation of antioxidant and antibacterial activities of fish protein hydrolysate produced from Malaysian fish sausage (Keropok Lekor) by-products by Indigenous Lactobacillus casei fermentation. J. Clean. Prod. 347, 131303 (2022).

-

Du, X. et al. pH-shifting formation of goat milk casein nanoparticles from insoluble peptide aggregates and encapsulation of Curcumin for enhanced dispersibility and bioactivity. LWT – Food Sci. Technol. 154, 112753 (2022).

-

Zheng, L. et al. Effects of Bacillus fermentation on the protein microstructure and anti-nutritional factors of soybean meal. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 65, 520–526 (2017).

-

Brahmi, Y. et al. Conformational study of protein interactions with hydrogen-passivated amorphous silicon surfaces: effect of pH. Appl. Surf. Sci. 423, 394–402 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support provided by the Vice President for Research and Technology of Gorgan University of Agricultural Sciences and Natural Resources, Gorgan, Iran.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Raei, P., Khomeiri, M., Sadeghi Mahoonak, A. et al. Evaluation of antibacterial and antioxidant activities of Sesame (Sesamum indicum) meal protein hydrolysate produced by Bacillus coagulans (IBRC 10807) fermentation. Sci Rep 15, 37870 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21765-1

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21765-1