Data availability

The main data supporting the findings of this study are available within this paper and its Supplementary Information. The raw and analysed datasets are too large to readily share publicly but are available for research purposes from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

-

Rohner, E., Yang, R., Foo, K. S., Goedel, A. & Chien, K. R. Unlocking the promise of mRNA therapeutics. Nat. Biotechnol. 40, 1586–1600 (2022).

-

Huang, X. et al. The landscape of mRNA nanomedicine. Nat. Med. 28, 2273–2287 (2022).

-

Jackson, L. A. et al. An mRNA vaccine against SARS-CoV-2—preliminary report. N. Engl. J. Med. 383, 1920–1931 (2020).

-

Liu, C. et al. mRNA-based cancer therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Cancer 23, 526–543 (2023).

-

Barbier, A. J., Jiang, A. Y., Zhang, P., Wooster, R. & Anderson, D. G. The clinical progress of mRNA vaccines and immunotherapies. Nat. Biotechnol. 40, 840–854 (2022).

-

Frankiw, L., Baltimore, D. & Li, G. Alternative mRNA splicing in cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 19, 675–687 (2019).

-

Lorentzen, C. L., Haanen, J. B., Met, Ö & Svane, I. M. Clinical advances and ongoing trials of mRNA vaccines for cancer treatment. Lancet Oncol. 23, e450–e458 (2022).

-

Dolgin, E. Personalized cancer vaccines pass first major clinical test. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 22, 607–609 (2023).

-

Blagden, S. P. & Willis, A. E. The biological and therapeutic relevance of mRNA translation in cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 8, 280–291 (2011).

-

Vitale, I., Shema, E., Loi, S. & Galluzzi, L. Intratumoral heterogeneity in cancer progression and response to immunotherapy. Nat. Med. 27, 212–224 (2021).

-

Martin, J. D., Cabral, H., Stylianopoulos, T. & Jain, R. K. Improving cancer immunotherapy using nanomedicines: progress, opportunities and challenges. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 17, 251–266 (2020).

-

Junttila, M. R. & de Sauvage, F. J. Influence of tumour micro-environment heterogeneity on therapeutic response. Nature 501, 346–354 (2013).

-

Johnson, D. B., Nebhan, C. A., Moslehi, J. J. & Balko, J. M. Immune-checkpoint inhibitors: long-term implications of toxicity. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 19, 254–267 (2022).

-

Hotz, C. et al. Local delivery of mRNA-encoded cytokines promotes antitumor immunity and tumor eradication across multiple preclinical tumor models. Sci. Transl. Med. 13, eabc7804 (2021).

-

Hausser, J. & Alon, U. Tumour heterogeneity and the evolutionary trade-offs of cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 20, 247–257 (2020).

-

Krysko, D. V. et al. Immunogenic cell death and DAMPs in cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 12, 860–875 (2012).

-

Galluzzi, L., Buqué, A., Kepp, O., Zitvogel, L. & Kroemer, G. Immunogenic cell death in cancer and infectious disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 17, 97–111 (2017).

-

Meier, P., Legrand, A. J., Adam, D. & Silke, J. Immunogenic cell death in cancer: targeting necroptosis to induce antitumour immunity. Nat. Rev. Cancer 24, 299–315 (2024).

-

Galon, J. & Bruni, D. Approaches to treat immune hot, altered and cold tumours with combination immunotherapies. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 18, 197–218 (2019).

-

Li, F. et al. mRNA lipid nanoparticle-mediated pyroptosis sensitizes immunologically cold tumors to checkpoint immunotherapy. Nat. Commun. 14, 4223 (2023).

-

Li, Y. et al. Multifunctional oncolytic nanoparticles deliver self-replicating IL-12 RNA to eliminate established tumors and prime systemic immunity. Nat. Cancer 1, 882–893 (2020).

-

Zhang, D. et al. Enhancing CRISPR/Cas gene editing through modulating cellular mechanical properties for cancer therapy. Nat. Nanotechnol. 17, 777–787 (2022).

-

Van Hoecke, L. et al. Treatment with mRNA coding for the necroptosis mediator MLKL induces antitumor immunity directed against neo-epitopes. Nat. Commun. 9, 3417 (2018).

-

Kon, E., Ad-El, N., Hazan-Halevy, I., Stotsky-Oterin, L. & Peer, D. Targeting cancer with mRNA–lipid nanoparticles: key considerations and future prospects. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 20, 739–754 (2023).

-

Gaur, A. et al. Characterization of microRNA expression levels and their biological correlates in human cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 67, 2456–2468 (2007).

-

Volinia, S. et al. A microRNA expression signature of human solid tumors defines cancer gene targets. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 2257–2261 (2006).

-

Dhawan, A., Scott, J. G., Harris, A. L. & Buffa, F. M. Pan-cancer characterisation of microRNA across cancer hallmarks reveals microRNA-mediated downregulation of tumour suppressors. Nat. Commun. 9, 5228 (2018).

-

Feikin, D. R. et al. Duration of effectiveness of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 disease: results of a systematic review and meta-regression. Lancet 399, 924–944 (2022).

-

Vandenabeele, P., Bultynck, G. & Savvides, S. N. Pore-forming proteins as drivers of membrane permeabilization in cell death pathways. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 24, 312–333 (2023).

-

Pasparakis, M. & Vandenabeele, P. Necroptosis and its role in inflammation. Nature 517, 311–320 (2015).

-

Hildebrand, J. M. et al. Activation of the pseudokinase MLKL unleashes the four-helix bundle domain to induce membrane localization and necroptotic cell death. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 15072–15077 (2014).

-

Faramin Lashkarian, M. et al. MicroRNA-122 in human cancers: from mechanistic to clinical perspectives. Cancer Cell Int 23, 29 (2023).

-

Hsu, S. H. et al. Essential metabolic, anti-inflammatory, and anti-tumorigenic functions of miR-122 in liver. J. Clin. Invest. 122, 2871–2883 (2012).

-

Galluzzi, L., Guilbaud, E., Schmidt, D., Kroemer, G. & Marincola, F. M. Targeting immunogenic cell stress and death for cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 23, 445–460 (2024).

-

Mensurado, S., Blanco-Domínguez, R. & Silva-Santos, B. The emerging roles of γδ T cells in cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 20, 178–191 (2023).

-

Mantovani, A., Allavena, P., Marchesi, F. & Garlanda, C. Macrophages as tools and targets in cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 21, 799–820 (2022).

-

Oliveira, G. & Wu, C. J. Dynamics and specificities of T cells in cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 23, 295–316 (2023).

-

Cho, Y. et al. Phosphorylation-driven assembly of the RIP1-RIP3 complex regulates programmed necrosis and virus-induced inflammation. Cell 137, 1112–1123 (2009).

-

Najafov, A., Chen, H. & Yuan, J. Necroptosis and cancer. Trends Cancer 3, 294–301 (2017).

-

Kim, S. et al. Improvement of therapeutic effect via inducing non-apoptotic cell death using mRNA-protection nanocage. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 13, 2400240 (2024).

-

Dondelinger, Y. et al. MLKL compromises plasma membrane integrity by binding to phosphatidylinositol phosphates. Cell Rep. 7, 971–981 (2014).

-

Hänggi, K. et al. Interleukin-1α release during necrotic-like cell death generates myeloid-driven immunosuppression that restricts anti-tumor immunity. Cancer Cell 42, 2015–2031.e2011 (2024).

-

Seifert, L. et al. The necrosome promotes pancreatic oncogenesis via CXCL1 and Mincle-induced immune suppression. Nature 532, 245–249 (2016).

-

Dagogo-Jack, I. & Shaw, A. T. Tumour heterogeneity and resistance to cancer therapies. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 15, 81–94 (2018).

-

Li, B. et al. Combinatorial design of nanoparticles for pulmonary mRNA delivery and genome editing. Nat. Biotechnol. 41, 1410–1415 (2023).

-

Chen, J. et al. Combinatorial design of ionizable lipid nanoparticles for muscle-selective mRNA delivery with minimized off-target effects. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2309472120 (2023).

-

Hewitt, S. L. et al. Durable anticancer immunity from intratumoral administration of IL-23, IL-36γ, and OX40L mRNAs. Sci. Transl. Med. 11, eaat9143 (2019).

-

Feng, Z. et al. An in vitro-transcribed circular RNA targets the mitochondrial inner membrane cardiolipin to ablate EIF4G2+PTBP1+ pan-adenocarcinoma. Nat. Cancer 5, 30–46 (2024).

-

Jain, R. et al. MicroRNAs enable mRNA therapeutics to selectively program cancer cells to self-destruct. Nucleic Acid Ther. 28, 285–296 (2018).

-

Xiao, Y. & Shi, J. Lipids and the emerging RNA medicines. Chem. Rev. 121, 12109–12111 (2021).

-

Eygeris, Y., Gupta, M., Kim, J. & Sahay, G. Chemistry of lipid nanoparticles for RNA delivery. Acc. Chem. Res. 55, 2–12 (2021).

-

Zhang, Y., Sun, C., Wang, C., Jankovic, K. E. & Dong, Y. Lipids and lipid derivatives for RNA delivery. Chem. Rev. 121, 12181–12277 (2021).

-

Miao, L. et al. Delivery of mRNA vaccines with heterocyclic lipids increases anti-tumor efficacy by STING-mediated immune cell activation. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 1174–1185 (2019).

-

Khoury, M. K., Gupta, K., Franco, S. R. & Liu, B. Necroptosis in the pathophysiology of disease. Am. J. Pathol. 190, 272–285 (2020).

-

Xu, Y. et al. AGILE platform: a deep learning powered approach to accelerate LNP development for mRNA delivery. Nat. Commun. 15, 6305 (2024).

-

Charni-Natan, M. & Goldstein, I. Protocol for primary mouse hepatocyte isolation. STAR Protoc. 1, 100086 (2020).

-

Li, J., Yao, Q. & Liu, D. Hydrodynamic cell delivery for simultaneous establishment of tumor growth in mouse lung, liver and kidney. Cancer Biol. Ther. 12, 737–741 (2011).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the staff at STTARR and ARC at the University Health Network for their assistance with animal work. Special gratitude is extended to L. Radvanyi for providing the 4T1-Fluc cell line, and to J. Hu and P. Zhang for generously providing the reporter T-cell line. This work was supported by the Princess Margaret Cancer Foundation’s Invest in Research Grant, Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (number RGPIN-2023-05124), the Canada Research Chairs Program (number CRC-2022-00575), Canadian Institutes of Health Research (numbers PJH-185722, PJT-190109, PJT-192011, PJT-195669), the Connaught Fund (number 514681), the J. P. Bickell Foundation (number 515159), New Frontiers in Research Fund—Exploration (number NFRFE-2023-00203) and the Canada Foundation for Innovation—John R. Evans Leaders Fund (number 43711).

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

S.D., S.T., H.H.H. and B.L. have filed an invention disclosure for the TITUR platform. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Nanotechnology thanks Guideng Li and Michael Mitchell for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

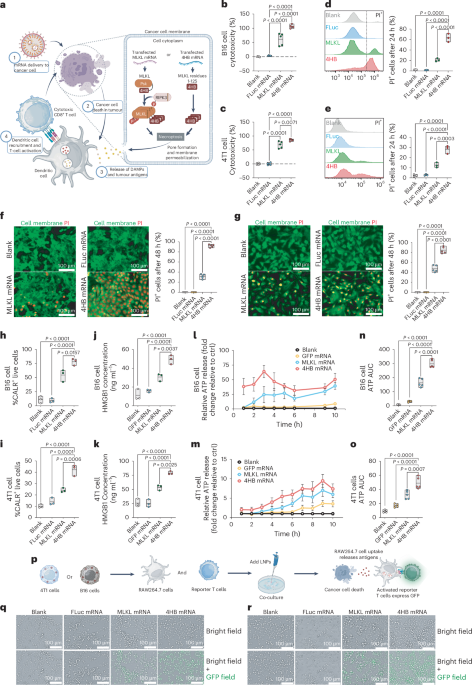

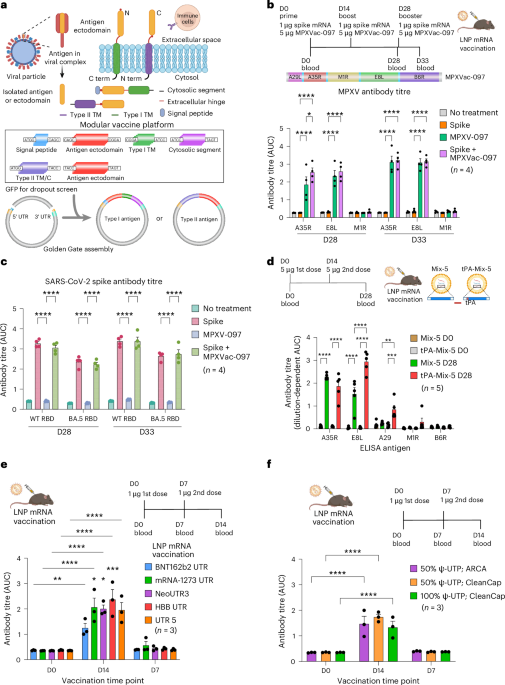

Extended Data Fig. 1 Tumour customized UTRs (TURs) improves therapeutic outcomes and of 4HB mRNA in B16 tumour models.

a, Summary of groups and experimental timeline for testing 4HB TI-LNPs or 4HB TITUR alone and in combination with anti-PD-1 in B16 tumour-bearing mice. b, Therapeutic efficacy and safety in B16 tumour models. Monitoring of B16 tumour size, shown as the mean and standard deviation at each timepoint, as well as the individual curves for each treatment group, for n=5 mice per group. Data are plotted as the mean ± s.d. c. Endpoint tumour size for the B16 model, shown as a box plot with the mean, maximum, and minimum measurements from n=5 mice per group. The endpoint represents the final tumour size monitoring day or once tumour size exceeded 1000 mm3. d. Weight changes relative to the mouse body weight on the first LNP injection day in the B16, for n=5 mice per group. Data are plotted as the mean ± s.d. e.Tissue sectioning and H&E staining of the liver of B16 models, as well as serum levels of liver damage markers, ALT and AST, at the endpoint of the study. Shown are box plots representing the mean, maximum, and minimum measurement in each organ with n=5 mice per group. Scale bar, 100 um. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons. All data are plotted as the mean ± s.d.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Tumour customized UTRs (TURs) improves therapeutic outcomes and of 4HB mRNA in 4T1 tumour models.

a, Summary of groups and experimental timeline for testing 4HB TI-LNPs or 4HB TITUR alone and in combination with anti-PD-1 in 4T1-Fluc tumour-bearing mice. b, Monitoring of 4T1-Fluc tumour model based on changes in tumour luminescence signals with representative IVIS images of 4T1-Fluc tumour luminescence from Day 0 to Day 30 following the first LNP dose. Colour bar corresponds to luminescence intensity corresponding to this scale. c. Quantification of 4T1-Fluc tumour bioluminescence signal overtime, shown as individual curves for each mouse in a treatment group. d. Endpoint tumour luminescence for 4T1-Fluc models, shown as a box plot with the mean, maximum, and minimum measurements from n=5 mice per group. e. Weight changes relative to the mouse body weight on the first LNP injection day in the 4T1-Fluc tumour models. Data are plotted as the mean ± s.d. f. Tissue sectioning and H&E staining of the liver and spleen in 4T1-Fluc models, as well as serum levels of liver damage markers. Scale bar, 100 um. g. ALT and AST, at the endpoint of the study. Shown are box plots representing the mean, maximum, and minimum measurement in each organ with n=5 mice per group. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Cancer vaccination effect of TITUR-B16 LNPs in bilateral B16 tumour model.

a, Tumour growth on both the treated and untreated flanks was monitored in B16 tumour-bearing mice following treatment with PBS, free 4HB mRNA, anti-PD-1, m4HBCtrlTIB16-2+anti-PD-1, m4HB TITURB16, m4HB TITURB16+anti-PD-1. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation for each group (n = 5), along with individual tumour growth curves for each mouse. b, Violin plots representing the percentage of each immune cell population in the tumour, spleen, and lymph nodes with n=5 mice per treatment group. c. Heatmaps showing cytokine levels of tumour tissues at the endpoint of the B16 dual tumour. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Cancer vaccination effect of TITUR-4T1 LNPs in 4T1 recurrence tumour model.

a, Tumour luminescence monitoring for primary and rechallenge 4T1-Fluc orthotopic tumours. Data is shown as IVIS images for each mouse, with n=5 mice per treatment group. Colour bar corresponds to luminescence intensity corresponding to this scale. b, Violin plots representing the percentage of each immune cell population in the tumour, spleen, and lymph nodes with n=5 mice per treatment group. c. Cytokine levels for each mouse per treatment group are shown in the heatmap, with n=5 mice per group. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Dong, S., Tsai, S.N., Xu, Y. et al. A modular mRNA platform for programmable induction of tumour-specific immunogenic cell death. Nat. Nanotechnol. (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41565-025-02045-5

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41565-025-02045-5