Introduction

Watermeal (Wolffia globosa), the smallest known flowering plant in the family Lemnaceae, has attracted growing interest as a sustainable food source owing to its rapid growth, rich nutritional profile, and diverse biochemical composition1,2,3,4,5. Its efficient conversion of nutrients into biomass supports applications ranging from animal feed6, biofuel production7,8,9, to human nutrition1,2,10,11.

In Thailand, W. globosa, locally known as Khai-nam, Khai-pum, Kai nhae, or Pum2,4, is traditionally consumed and valued for its nutritional benefits. The species is characterized by high protein content (29.6–48.2%), carbohydrates (38.41–52.59%), fat (5.18–9.6%), fiber (9.98–36.52%), and ash (10.73–20.43%) on a dry weight basis3,11,12,13,14. It also provides essential amino acids and bioactive compounds, including phenolics and flavonoids, which exhibit potent antioxidant, antidiabetic activities11,15,16. These properties confer significant health benefits, positioning W. globosa as a genuine nutraceutical. Importantly, toxicological evaluations indicate its safety for human consumption, with no observed adverse effects in animal studies3.

The incorporation of W. globosa into food products, particularly snacks, has shown promise in improving their nutritional profile by increasing antioxidant content. Enriched snacks exhibit elevated levels of phenolics and flavonoids, as well as enhanced antioxidant activity compared to control samples11. Additionally, polyphenol intake from W. globosa has been associated with reduced intrahepatic fat accumulation17. Given these nutraceutical benefits, interest in its use as a novel functional food ingredient is growing, prompting research into more cost-effective and scalable cultivation methods to maximize both yield and nutritional value.

The growth and biochemical composition of W. globosa are strongly influenced by nutrient availability in the cultivation medium. Although previous studies have explored hydroponic solutions, chemical fertilizers, organic substrates (e.g., pig manure), and specialized formulations4,8,12,13,18, the effects of green microalgae-based and vitamin B complex-enriched media on both biomass yield and nutritional quality of W. globosa for food applications remain unexamined.

Given the close ecosystem relationship between green microalgae and W. globosa, established microalgal media provide a relevant framework, particularly as B-vitamins and iron (Fe) are known to enhance growth by supporting metabolism and antioxidant activity19,20,21,22. In practice, NPK fertilizers are widely used for watermeal cultivation due to their low cost, yet they lack essential micronutrients. Investigating the use of vitamin-enriched fertilizers and algal culture media could therefore help optimize biomass productivity and reduce production costs. Moreover, assessing how different media affect the biochemical composition of W. globosa, particularly protein content, is critical for evaluating its potential as a functional food. To address these aspects, the effects of vitamin B complex and iron supplementation on NPK-based media to enhance both growth performance and nutritional quality should be studied.

The increasing global focus on health and wellness has fueled demand for foods that not only taste good but also provide enhanced nutritional value. Despite this trend, many traditional foods continue to be valued primarily for their sensory qualities. For example, Khanoom Kai Nok Krata, a popular Thai street snack made from fried sweet potato balls, is beloved for its sweet aroma and distinctive texture-crispy on the outside yet soft and chewy inside. Likewise, fresh pasta is highly regarded across various cuisines for its tender texture and rich flavor, attributes largely derived from its higher moisture content and the inclusion of eggs in the dough. While both foods are appreciated for their sensory appeal, they are predominantly carbohydrate-based and relatively low in protein, micronutrients, and antioxidants. This nutritional limitation contrasts with the rising consumer demand for products that combine taste with functional health benefits.

To address this challenge, the present study incorporates W. globosa, a nutrient-dense aquatic plant rich in protein, essential amino acids, vitamins, and minerals, into these traditional foods. Moreover, previous studies have shown that the nutritional and functional properties of W. globosa are strongly influenced by the cultivation medium. Building on this knowledge, the study evaluates the growth performance and biochemical composition of W. globosa under different nutrient conditions and examines its effects when incorporated into fresh pasta and fried sweet potato balls. Specifically, the study investigates how this integration influences both the nutritional profile and the sensory characteristics of these foods. The findings are expected to contribute to sustainable cultivation strategies and support the development of functional food products that preserve cultural identity while meeting modern health-conscious preferences.

Materials and methods

Plant material and starter culture preparation

Samples of Wolffia globosa were collected from a reservoir at the School of Agricultural Technology, King Mongkut’s Institute of Technology Ladkrabang (Bangkok, Thailand), and subsequently isolated for cultivation. The isolated samples were rinsed with tap water, disinfected in 10 ppm potassium permanganate (KMnO₄) for 30 min, and thoroughly washed with deionized water. The cleaned material was cultured in 1 L glass flasks containing 0.1 g L⁻1 16-16-16 NPK fertilizer under continuous illumination (3,000 Lux). After reaching full growth, plants were transferred to 100 L fiberglass tanks for outdoor cultivation and subsequently to a 3,000 L cement pond (1 m × 5 m × 0.6 m; water depth 0.5 m). The pond was supplemented with 16-16-16 NPK fertilizer for one weeks to establish a starter culture. The NPK fertilizer was applied at 10 g per 100 L of water. This dosage, initially suggested by farmers cultivating watermeal in earthen ponds, was validated in fiberglass tanks, where higher levels (15 and 20 g per 100 L) were found to produce no significant increase in biomass yield.

Experimental design: cultivation in different nutrient media

Prior to experimentation, stock cultures of W. globosa were acclimated in dechlorinated tap water for three days to stabilize growth conditions. Following acclimation, the cultures were transferred to four nutrient treatments, with the composition and concentration of chemicals in each treatment provided in Table 1.

- 1.

AB medium: Commercial hydroponic fertilizer

- 2.

Chlorella medium23: Microalgae medium, nutrient composition suitable for green microalgae

- 3.

16-16-16: Chemical fertilizer (NPK 16-16-16)

- 4.

16-16-16-B: Chemical fertilizer (NPK 16-16-16) supplemented with vitamin B complex (per tablet: 100 mg vitamin B1, 7.5 mg B6, 0.075 mg B12) and FeSO4

All chemicals were purchased from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). The chemical fertilizer was obtained from a local agricultural supply store, and Vitamin B complex was purchased from the Government Pharmaceutical Organization (Bangkok, Thailand).

The experiment was conducted using 100 L fiberglass tanks (surface area: 0.8 m2; water depth: 19 cm), each serving as an independent cultivation unit. Each treatment was performed with four replicate tanks. Fresh W. globosa (40 g) was inoculated into each tank, occupying approximately 30% of the surface area to ensure optimal initial coverage for growth. This inoculation density was selected based on preliminary tests, which showed that densities exceeding 30% coverage resulted in overcrowding within 7 days of cultivation. This overcrowding limited light access for some plants, leading to a slower growth rate and potential experimental error. The tanks were exposed to natural sunlight by placing them outdoors, adjacent to a building, and a black shade net was installed to moderate light intensity and maintain water temperature below 31 °C- a threshold known to inhibit W. globosa growth24. Daily maintenance involved checking water levels and compensating for evaporative losses with dechlorinated tap water. The nutrient media was replaced at week 4 to ensure a consistent nutrient supply, prevent contamination from other organisms, and reduce water turbidity.

Key environmental parameters, including temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen (DO), electrical conductivity, and light intensity, were measured every three days using standard field instruments. This was done to ensure consistent data collection across all replicates and treatments. Specifically, a HANNA Model 5521 pH and EC meter was used to measure pH and electrical conductivity, a YSI Model 5100 DO meter for dissolved oxygen, and a Handsun Model LX-1020B LUX meter for light intensity.

To isolate the effect of nutrient formulation on biomass productivity and biochemical composition, the experiment was conducted during a single cultivation season under controlled environmental conditions. Although W. globosa can be grown year-round, previous studies have shown that its optimal growth occurs within a temperature range of 20–31 °C24. This range can be consistently maintained across seasons through shading and strategic tank placement, allowing external seasonal variability to be minimized. As such, seasonal effects were intentionally excluded from this study’s scope to better isolate the influence of nutrient media.

Growth performance measurement

Biomass was harvested weekly, and 40 g of fresh biomass was reintroduced each time. Growth performance was evaluated using25:

-

Specific Growth Rate (SGR) (day−1) = [ln(final weight)—ln(initial weight)] / number of days

-

Average Daily Growth (g FW day−1) = (final weight—initial weight) / number of days

-

Daily Productivity (g FW m−2 day−1) = average daily growth / water surface area (m2)

-

Biomass Yield (g FW tank−1) = final weight—initial weight

Where FW = fresh weight.

At the end of the experiment, biomass from each treatment was analyzed for chlorophyll-a, carotenoids, protein, fat, carbohydrate, fiber, ash, calcium, and phosphorus. Heavy metal and microbial contamination were assessed by the Institute of Food Research and Product Development.

Biomass scale-up and powder preparation

The nutrient treatment that provided the most favorable cost-to-benefit ratio (16-16-16-B) was selected for scale-up in a 3000 L cement pond. Biomass was harvested after seven days of cultivation, at which point the watermeal had completely covered the pond surface. If cultivation had been extended beyond this period, self-shading among fronds and the presence of weakened or dead cells in the harvested material would have occurred. To ensure that only fresh and high-quality biomass was obtained, harvesting was conducted on day seven. The harvested biomass was subsequently cleaned, drained, and oven-dried at 45 °C for 6–8 h (target moisture <12%), and ground into powder. The powder was sieved (0.25 mm mesh), packed in opaque, sealed containers, and stored under refrigerated at 4 °C until further use.

Development of functional food products

Fresh pasta enrichment

Fresh pasta was fortified with dried W. globosa powder at four inclusion levels: 0 (control), 5, 7.5, and 10 g per 200 g of flour base (0, 2.5, 3.75, and 5% w/w). These concentrations were selected to enhance the nutritional profile while maintaining acceptable flavor and aroma qualities. Preliminary trials indicated that levels above 10 g significantly affected the pasta’s visual and olfactory attributes, resulting in an undesirable dark green–brown coloration and a strong grassy odor, both of which could negatively impact consumer acceptance.

The pasta dough formulation consisted of 200 g wheat flour, 50 g semolina, 2 g salt, 5 mL olive oil, and two eggs (approximately 150 g). This base recipe was adapted to improve dough consistency and handling properties, as the inclusion of W. globosa powder decreased dough cohesiveness. Adjustments to the egg and oil content were made to optimize the dough’s binding capacity. All ingredients were food-grade and sourced from a local retail outlet.

To prepare the pasta, W. globosa powder was first blended with wheat and semolina flours in a stainless-steel bowl. Salt, eggs, and olive oil were then incorporated, and the mixture was kneaded until a smooth, uniform dough was obtained. The dough was shaped into a ball, wrapped in plastic film, and rested at 4 °C for 30 min. Following refrigeration, the dough was rolled into thin sheets using a manual pasta roller and cut into standardized shapes. The pasta was then air-rested in a shaded environment for 20 min before blanching in boiling water for 4 min. Samples were subsequently used for nutritional analysis and sensory evaluation.

Fried sweet potato balls enrichment

The sweet potato ball recipe was developed in collaboration with a commercial street food vendor and comprised 160 g of mashed orange-fleshed sweet potato, 90 g tapioca starch, 30 g sugar, 1 g salt, 5 g baking powder, and 60 mL water. Fortification was achieved by incorporating dried W. globosa powder at four levels: 0 g (control), 2.5, 3.5, and 7 g, corresponding to 0, 0.9, 1.2, and 2.4% (w/w), respectively. These levels were selected based on preliminary trials, which indicated that higher concentrations (> 7 g) negatively affected dough cohesion, hindered the formation of uniform spherical shapes, and introduced an undesirable strong green odor characteristic of watermeal.

All food-grade ingredients were sourced from a local retail supplier. The prepared ingredients were manually kneaded to form a smooth, pliable dough, which was then divided and shaped into uniform spheres. The dough balls were rested at room temperature for 10 min prior to frying.

Deep-frying was carried out in vegetable oil maintained at 150–170 °C for approximately 10 min, with continuous stirring to ensure uniform cooking and prevent burning. During frying, a sieve was used to gently press and rotate the balls, promoting the formation of a crisp outer shell and a hollow interior. After frying, excess oil was drained, and the final products were evaluated for proximate composition and subjected to sensory analysis.

Nutritional and safety analysis

Watermeal powder, fried sweet potato balls, and fresh pasta were homogenized into composite samples. From each, four independent subsamples were randomly selected and analyzed once, representing four replicates.

Proximate Analysis: The proximate composition, including moisture, ash, protein, fat, crude fiber, calcium, and phosphorus, was determined following the procedures outlined in the AOAC (Association of Official Analytical Collaboration) Official Methods of Analysis26. Total carbohydrate content was calculated by difference, subtracting the measured values of moisture, protein, fat, and ash from 100%.

Pigment Analysis: Chlorophyll-a and carotenoid contents were quantified according to the methods described by Prosridee et al.18 and Becker27.

Heavy Metal Determination: Lead (Pb), cadmium (Cd), arsenic (As), and mercury (Hg) were analyzed according to AOAC Official Methods 999.10, 971.21, and 2015.01 using Graphite Furnace Atomic Absorption Spectrometry (GFAAS) and Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS)26.

Microbial Assessment: Total plate count was determined using ISO 4833-1/-2, yeast and mold using ISO 21527-1:2008, and coliforms using ISO 4832. Pathogenic bacteria including Salmonella spp. and Escherichia coli (generic and O157:H7) were analyzed according to ISO 6579-1, ISO 16649-1/-2, and ISO 1665426.

Sensory evaluation

Fifty untrained panelists (ages 18–50) without food allergies evaluated six sensory attributes (appearance, color, odor, taste, texture, overall acceptability) using a 9-point hedonic scale (1 = dislike extremely, 9 = like extremely). Each coded sample (approx. 20 g) was served individually. Water was provided for palate cleansing. Protocols followed standard sensory testing guidelines28.

Ethics declarations

Informed consent and data collection

All participants provided informed consent, and their data were kept anonymous and confidential. Before participation, we provided volunteers with comprehensive information on product ingredients and potential risks of the sensory evaluation. Participants were specifically instructed to perform a “taste and spit” procedure, ensuring no samples were ingested during the evaluation.

Approval for human experiments

Institutional Review Board Statement: The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by The Research Ethics Committee of King Mongkut’s Institute of Technology Ladkrabang (study code EC-KMITL_68_014; date of approval: 29 March 2025).

Statistical analysis

The experiment was conducted as a completely randomized design (CRD) with four replicates (n = 4). Data (mean ± SD) were analyzed by one-way ANOVA, followed by Duncan’s multiple range test, with significance set at p < 0.05 (SPSS v.18).

Results and discussion

Biomass of Wolffia globosa cultivation in different media

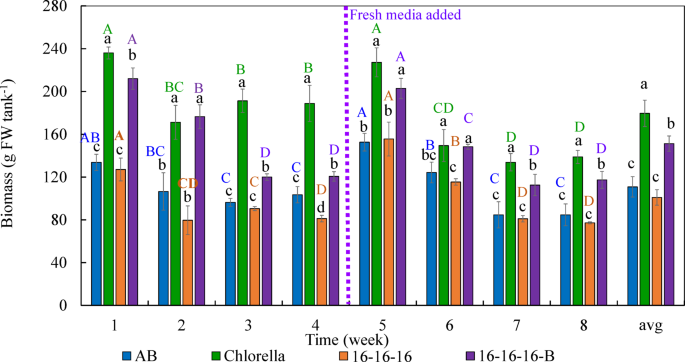

The biomass yield (calculated on a weekly basis) of W. globosa cultivated in four different media-AB, Chlorella, 16-16-16, and 16-16-16 supplemented with a vitamin B complex and FeSO4 (referred to as 16-16-16-B)-varied significantly over the eight-week cultivation period (p < 0.05; Fig. 1). Fresh media were applied at the beginning of the experiment, and a complete replacement of water and nutrients was performed in week four to maintain optimal growth conditions. Among the treatments, the Chlorella medium consistently produced the highest biomass yield, ranging from 133.82 ± 8.15 to 236.00 ± 5.54 g FW tank−1, followed by 16-16-16-B, AB, and 16-16-16 in descending order of effectiveness. Visual differences in plant appearance, particularly coloration, were also evident across treatments (Fig. 2).

Biomass production of watermeal W. globosa cultivated in different nutrient media across an 8-week period. Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) from four replicates. Different lowercase letters within the same week denote statistically significant differences among treatments (p < 0.05). Different uppercase letters within the same treatment denote statistically significant differences across weeks (p < 0.05).

Biomass production peaked during the first week, likely due to the initial abundance of nutrients. From weeks 2 to 4, a gradual decline was observed, though the differences were not statistically significant. Following the complete media replacement in week 4, biomass increased markedly in week 5, reaching levels comparable to the initial week. However, from weeks 6 to 8, biomass production significantly decreased again, likely due to nutrient depletion, increased turbidity. Initially, water exchange was planned based on a 50% reduction in electrical conductivity (EC) as an indicator of nutrient depletion. However, by week 4, EC remained at approximately 70% of the initial value, even as growth began to decline-prompt an earlier-than-anticipated full media renewal.

Over the entire cultivation period, the Chlorella medium yielded the highest average biomass (179.57 ± 12.30 g FW tank−1), significantly higher than the yields from 16-16-16-B (151.27 ± 7.20 g FW tank−1), AB (110.81 ± 9.51 g FW tank−1), and 16-16-16 (100.96 ± 6.92 g FW tank−1). These findings suggest that nutrient-rich media-such as Chlorella medium-or those fortified with vitamins, like 16-16-16-B, provide more favorable growth conditions than other media.

Growth performance also varied significantly among treatments throughout the eight-week period (p < 0.05) (Table 2). The Chlorella medium consistently resulted in the highest specific growth rate (0.70 ± 0.02–0.78 ± 0.00 day−1), daily growth rate (19.12 ± 1.16–33.71 ± 0.79 g FW day−1), and productivity (23.90 ± 1.06–42.14 ± 0.99 g FW m−2 day−1), outperforming all other treatments. The 16-16-16-B medium showed similarly robust growth, with specific growth rates ranging from 0.67 ± 0.01 to 0.76 ± 0.01 day−1, daily growth rates peaking at 30.29 ± 2.00 g FW day−1 (week 1) and 28.98 ± 1.36 g FW day−1 (week 5), and productivity reaching 37.86 ± 1.50 g FW m−2 day−1 and 36.22 ± 1.70 g FW m−2 day−1, respectively. In contrast, AB and 16-16-16 media showed lower and more inconsistent performance, although moderate improvements were observed after media replacement. Overall, nutrient composition was a key determinant of biomass production, with both Chlorella and 16-16-16-B media promoting significantly better growth outcomes across all measured parameters.

The superior performance of the Chlorella medium likely stems from its balanced nutrient profile. The 16-16-16-B medium, enriched with FeSO4, vitamins B1 (thiamine), B6 (pyridoxine), and B12 (cobalamin), also produced substantial yields, suggesting a physiological requirement for these cofactors. Thiamine and pyridoxine play central roles in carbohydrate and amino acid metabolism, stress tolerance, and antioxidant defense, while cobalamin is essential for one-carbon metabolism and nitrogen cycling. These vitamins are critical for eukaryotic plant metabolism, particularly in fluctuating aquatic environments where robust metabolic responses are necessary19,20,21,29,30,31.

While there have been no prior reports on the effects of vitamin B on the growth of duckweed species, its role in promoting the growth of various algae have been well-documented. For instance, vitamin B1 has been shown to significantly enhance the growth and hydrocarbon content of the green microalga Botryococcus braunii by 1.3- and 1.1-fold, respectively21. Similarly, vitamins B1, B2, B6, and B12 have been found to promote the growth of phytoplankton and increase total chlorophyll content by 87.5%32.

The relatively low yields observed in the AB hydroponic and standard 16-16-16 treatments highlight the need to optimize both macro- and micronutrients to maximize productivity. Additionally, the biomass resurgence following week 4 media replacement underscores the importance of periodic nutrient replenishment and removal of other aquatic organisms during long-term cultivation.

In this study, W. globosa cultivated in Chlorella medium under outdoor conditions achieved high biomass yields, with daily growth rates ranging from 19.12 ± 1.16 to 33.71 ± 0.79 g FW day−1 and productivity between 23.90 ± 1.06 and 42.14 ± 0.99 g FW m−2 day−1. The specific growth rate (SGR) ranged from 0.70 ± 0.02 to 0.78 ± 0.00 day−1 -higher than that reported for W. arrhiza grown in 10% Hoagland solution (0.18 ± 0.00 day−1) by Faizal et al.8 Ruekaewma et al.12 reported a yield of 1.52 ± 0.04 g DW m−2 day−1 using Modified Hutner’s medium (DW = dry weight), while this study achieved a significantly higher yield of 4.83 ± 0.11 g DW m−2 day−1 (This value was obtained by drying fresh samples from this experiment 42.14 ± 0.99 g in an oven at 105 °C for 24 h). Said et al.13 reported even greater productivity for W. globosa cultivated with commercial hydroponic fertilizer outdoors (64.62–120.6 g day−1 and 97.75–176.65 g m−2 day−1); however, indoor growth rates were considerably lower (0.67–1.50 g day−1 and 25.88–64.56 g m−2 day−1). Sirirustananun et al.4 also reported high growth rates (31.52 ± 0.24 to 44.35 ± 1.81 g day−1) for W. arrhiza in hydroponic systems.

Medium cost analysis (Table 1) revealed that the frequency of water exchange and nutrient replenishment had a substantial impact. Weekly replenishment incurred relatively high costs (1.77–284.35 THB kg−1), whereas extending the interval to four weeks substantially lowered costs to 0.62–91.69 THB kg−1. Accordingly, a four-week replenishment cycle was considered more economically feasible and practical for large-scale cultivation. Previous studies reported that cultivation of W. globosa using NPK 15-15-15 fertilizer at concentrations of 16–36 g tank⁻1 resulted in medium costs of 3.73–7.21 THB kg−133.

Among the tested media, the Chlorella medium yielded the highest biomass but incurred the highest medium cost. Although the 16-16-16 medium had the lowest cost, it also produced the lowest biomass, protein, and chlorophyll-a content. Comparatively, 16-16-16-B showed significantly better results across all growth and nutritional parameters (Fig. 1; Tables 2, 4). Therefore, while 16-16-16-B entails slightly higher costs than 16-16-16, its superior nutritional quality makes it the preferred medium for producing W. globosa as a functional food ingredient.

In Thailand, W. globosa is commonly cultivated using 16-16-16 fertilizer due to its low medium cost, which averages approximately 0.62 THB per kilogram of fresh biomass. However, the present study demonstrates that supplementing this fertilizer with a vitamin B complex and FeSO4-despite increasing the medium cost to 3.39 THB per kilogram-remains economically viable and profitable for farmers. Given the current market price of W. globosa, which ranges from 80 to 120 THB per kilogram, the return on investment remains substantial even with the added input cost.

Beyond the economic perspective, the addition of vitamin B complex significantly enhances the nutritional profile of W. globosa, leading to increased levels of chlorophyll-a, carotenoids, and protein. These improvements offer added value for health-conscious consumers. Furthermore, the vitamin B supplementation was found to enhance daily biomass productivity by approximately 1.7-fold compared to cultivation with 16-16-16 fertilizer alone. This approach represents a promising strategy to simultaneously improve the profitability and nutritional quality of W. globosa cultivation systems.

Physicochemical parameters of the culture water

While this study utilized an outdoor cultivation setup, the experimental aim was to isolate the effect of the different media. This was achieved by placing all experimental setups in locations that received similar light and temperature conditions.

Table 3 summarizes the environmental parameters, including water temperature, light intensity, pH, dissolved oxygen (DO), and electrical conductivity (EC). The data shows that the water temperature, ranging from 27.49 to 27.55 °C, was consistently within the optimal range of 20–31 °C for watermeal growth24. Furthermore, there were no significant differences in light intensity among the treatments (p > 0.05), ensuring uniform light exposure. Therefore, it can be confidently concluded that the observed variations in watermeal growth or biochemical composition were not influenced by differences in light or temperature.

No statistically significant differences in DO concentrations were found across any of the experimental treatments, despite minor variations observed. The Chlorella medium exhibited the highest DO at 8.08 ± 0.12 mg L−1, followed closely by the AB medium at 8.02 ± 0.14 mg L−1. The primary source of DO in the cultivation tanks is photosynthesis by watermeal. The observed consistency in DO levels across different watermeal densities may be due to the biomass differences (Fig. 1) being insufficient to cause a significant change. An alternative explanation is that excess oxygen produced was lost to the atmosphere, with the measured DO values aligning with the oxygen saturation point for water at 27–28 °C34.

The pH of water is a critical factor that influences nutrient availability for aquatic plants by affecting the solubility and ionic state of essential elements. Elevated pH can lead to the precipitation of various ions, thereby limiting their cellular uptake and utilization for growth. As reported by Baek et al.35, duckweed species thrive best in a pH range of 6.5–7.5, although they can tolerate a wider range from 5 to 9.

Our results showed a significant difference in pH among treatments, with the Chlorella medium recording the highest value (8.22 ± 0.05) and the AB medium the lowest (7.65 ± 0.05). These values are slightly above the previously established optimal range for duckweed growth. High pH levels are known to increase NH₄+ concentrations, which can potentially inhibit anion transport across the plant’s cell membrane and reduce overall growth 35.

Interestingly, the Chlorella medium, despite its elevated pH, supported the highest biomass, suggesting that a pH of 8.22 was not inhibitory to watermeal growth in this experiment. It can therefore be concluded that the lower pH levels in the other treatments were also not detrimental. The high pH in the Chlorella medium may be a result of its unique chemical composition, combined with the high rate of photosynthesis from the maximum biomass (Fig. 1), which led to significant CO₂ drawdown and a subsequent rise in pH.

Electrical conductivity reflects the concentration of dissolved ions in nutrient solutions. While higher EC indicates greater nutrient availability, excessive levels can cause osmotic stress and ion toxicity, impairing growth and reducing macromolecule accumulation in duckweed36,37.

In this study, EC varied widely among treatments. The Chlorella medium showed the highest EC value (2116.52 ± 76.61 µS cm−1), indicating the highest ionic strength and nutrient content. This high EC is likely due to the concentrated chemical composition of the medium (Table 1). Despite this high EC level, the Chlorella medium did not appear to cause any osmotic stress or adverse effects on watermeal. This conclusion is supported by the fact that this treatment resulted in the highest specific growth rate and overall biomass, especially during the first week after cultivation in fresh media (Table 2).

However, EC alone did not predict growth performance. The 16-16-16-B medium, with a lower EC (582.32 ± 11.29 µS cm⁻1), supported superior growth compared with the AB medium (1171.03 ± 30.90 µS cm⁻1). This result was likely due to the vitamin B complex and FeSO₄ present in 16-16-16-B but absent in AB, which played a critical role in promoting watermeal growth. These findings suggest that watermeal growth depends more on nutrient composition than on overall ionic strength.

Biochemical composition of fresh Wolffia globosa cultivation in different media

The cultivation medium was found to significantly influence the biochemical composition of W. globosa (Table 4). The highest chlorophyll-a content was observed in samples grown in AB medium, with successively lower levels in Chlorella medium, 16-16-16-B, and 16-16-16. This trend is consistent with the visual color variations of the watermeal, as depicted in Fig. 2.

W. globosa grown in the AB medium exhibited the significantly highest chlorophyll-a (4.08 ± 0.00%) and carbohydrate contents (37.21 ± 1.12%), indicating enhanced photosynthetic activity and carbohydrate accumulation under this formulation. In contrast, the highest protein content (46.10 ± 0.93%) was observed in W. globosa cultivated in the Chlorella medium. This result is likely attributable to the higher and more bioavailable nitrogen content in this medium, which is known to promote protein biosynthesis. These findings are consistent with previous reports by Ruekaewma et al.12, who reported 48.2% protein in W. globosa, and by Said et al.13, who found a protein content of 45.04 ± 4.37%. In comparison, earlier studies by Chantiratikul et al.38 and On-Nom et al.11 reported lower protein levels of 29.6% and 31.50%, respectively.

The highest carotenoid content (3.36 ± 0.00%) was observed in W. globosa grown in the 16-16-16-B medium, although it was not significantly different from the AB medium (3.07 ± 0.02%). Carotenoids such as lutein and violaxanthin are well-documented in Wolffia species1,2 and are valued for their antioxidant and cholesterol-lowering properties. Fat content did not differ significantly among treatments, ranging from 14.17 ± 1.96% to 15.50 ± 1.84%. These values are notably higher than those reported in previous studies, where fat contents typically ranged from 5.18 to 9.6%11,12,13.

The highest crude fiber content (15.79 ± 0.36%) was recorded in W. globosa grown in the 16-16-16 medium. This result is comparable to the 14.5% crude fiber reported by Ruekaewma et al.12, higher than the 9.98% reported by Said et al.13, but considerably lower than the 36.52% reported by On-Nom et al.11. In addition to high fiber content, the 16-16-16 medium also resulted in the highest calcium content (1.33 ± 0.03%).

These findings clearly demonstrate that the nutrient composition of the cultivation medium significantly affects the biochemical profile of W. globosa. The Chlorella medium resulted in the highest protein content, while the 16-16-16-B medium promoted the greatest accumulation of carotenoids. In contrast, the AB medium enhanced chlorophyll-a and carbohydrate levels. Additionally, cultivation in the 16-16-16 medium led to increased fiber and calcium content, indicating its potential for improving structural and mineral components39. Safety assessments confirmed that all media produced W. globosa free of heavy metals and pathogens, with microbial counts within acceptable limits40, verifying suitability for food applications.

The findings indicate that watermeal cultivated in the 16-16-16-B medium is safe for consumption. Although its protein content (42.48 ± 0.87%) was significantly lower than that obtained with the Chlorella medium, it remained comparatively high and within the range reported in previous studies11,12,13,38. In addition, this treatment yielded the highest carotenoid content (3.36 ± 0.00%). Considering both the nutritional profile (Table 4) and cost-effectiveness (Table 2), the 16-16-16-B medium was selected for large-scale outdoor cultivation in cement ponds, with biomass harvested every seven days for use in functional food development. The harvested biomass was subsequently dried and utilized as raw material for product formulation.

Nutritional analysis of the dried sample revealed the following composition (% dry weight): chlorophyll-a 2.35 ± 0.02, carotenoids 3.79 ± 0.04, carbohydrate 22.22 ± 1.13, fat 13.59 ± 1.05, protein 39.95 ± 2.68, fiber 0.82 ± 0.00, calcium 0.045 ± 0.000, and ash 0.59 ± 0.00. Furthermore, all food safety parameters met standard criteria, confirming W. globosa as a safe and nutrient-rich candidate for functional food applications.

Nutritional value of functional food products, fresh pasta and fried sweet potato balls, enriched with Wolffia globosa

The incorporation of dried W. globosa powder into fresh pasta and fried sweet potato balls significantly enhanced their nutritional profiles, as shown in Table 5. Fresh pasta fortified with increasing concentrations of W. globosa (5, 7.5, and 10 g) exhibited significant improvements (p < 0.05) in chlorophyll-a, carotenoid, protein, fiber, and calcium contents compared to the control. Chlorophyll-a levels increased markedly from 0.05 ± 0.00% to 1.66 ± 0.05%, while carotenoid content increased from 0.32 ± 0.00% to 0.78 ± 0.01%. These enhancements are consistent with previous reports indicating that W. globosa is a rich source of bioactive pigments1,2, which are known for their antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and cholesterol-lowering properties41.

Protein content also increased significantly, particularly at 7.5 g and 10 g supplementation levels, reaching 21.82 ± 1.19% compared to 17.66 ± 1.25% in the control. This result aligns with the high protein levels observed in W. globosa (Table 4). Dietary fiber content nearly doubled, rising from 8.08 ± 0.08% to 15.83 ± 0.02%, likely due to the presence of structural carbohydrates in W. globosa, which contributed to improved gastrointestinal function and reduced risk of metabolic disorders42. Additionally, calcium content increased significantly from 1.49 ± 0.01% to 2.11 ± 0.03%, reflecting the mineral-rich profile of W. globosa. Conversely, carbohydrate and fat contents decreased with higher W. globosa inclusion, likely due to its lower levels of these nutrients compared to wheat flour43. These results support the use of W. globosa as a nutrient-dense ingredient for enhancing the functional and health-promoting properties of pasta.

Similarly, fried sweet potato balls fortified with 1.75, 3.5, and 7 g of dried W. globosa exhibited comparable trends. The chlorophyll-a content increased significantly from 0.17 ± 0.03% to 1.11 ± 0.07%, while carotenoid levels rose from 1.55 ± 0.07% to 2.19 ± 0.10%, consistent with the high pigment content of W. globosa (Table 4). Carotenoids present in the control, non-W. globosa fortified sweet potato components of the fried sweet potato balls originated from sweet potatoes.

Protein levels increased from 6.17 ± 0.25% to 9.32 ± 0.22%, further confirming the protein-enriching effect of W. globosa observed in the earlier analysis. Fiber content also increased significantly from 23.66 ± 0.69% to 31.21 ± 0.63%, which may contribute to greater satiety, improved glycemic control, and digestive health44.

As with pasta, increases in W. globosa concentration led to reductions in carbohydrate and fat contents, which decreased from 47.48 ± 2.85% to 39.16 ± 0.26% and from 15.34 ± 0.13% to 11.75 ± 0.48%, respectively. Calcium content increased from 1.60 ± 0.20% to 2.10 ± 0.29%, although no statistically significant differences were observed in ash content.

Overall, the enrichment of functional food products with W. globosa significantly improved their nutritional composition, notably through increased levels of protein, fiber, calcium, and antioxidant pigments. These enhancements underscore the potential of W. globosa as a novel functional food ingredient with various health-promoting properties.

Sensory evaluation of fresh pasta and fried sweet potato balls enriched with Wolffia globosa

Sensory evaluation is a critical component in assessing consumer acceptance and the market potential of novel food products45. In this study, a 9-point hedonic scale was used to evaluate key sensory attributes-appearance, color, odor, taste, texture, and overall liking-of fresh pasta and fried sweet potato balls enriched with dried W. globosa. The visual appearance of enriched products is shown in Fig. 3, with sensory scores summarized in Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table S1.

Visual characteristics of fresh pasta (upper row) and fried sweet potato balls (lower row) formulated with varying concentrations of dried watermeal W. globosa powder.

Radar chart showing sensory evaluation of fresh pasta and fried sweet potato balls with varying concentrations of dried watermeal W. globosa, assessed using a 9-point hedonic scale (1 = dislike extremely, 9 = like extremely).

For fresh pasta, increasing the concentration of dried W. globosa resulted in significant improvements in all sensory parameters compared to the control (0 g). The formulation containing 10 g of W. globosa achieved the highest ratings for appearance (7.60 ± 0.52), color (7.99 ± 0.58), odor (8.17 ± 0.48), taste (7.81 ± 0.52), texture (7.96 ± 0.52), and overall liking (7.52 ± 0.60). These values were significantly higher than those of the control, which consistently received the lowest scores. Based on the 9-point hedonic scale, overall liking scores between 7.0 and 7.5 reflect a strong consumer preference (“like moderately” to “like very much”)46, indicating favorable acceptance of the enriched pasta.

The improved color and appearance were likely attributed to the natural chlorophyll and carotenoid pigments in W. globosa, which impart a vibrant green hue. The higher odor and taste scores may be explained by bioactive compounds and free amino acids that influence flavor characteristics, such as asparagine, glycine, and arginine, which enhance sweetness, reduce bitterness, and strengthen umami perception47,48. These sensory improvements are particularly relevant for the development of functional food products, as they suggest that W. globosa not only enhances nutritional quality but also contributes positively to consumer acceptability.

The improvement in texture scores may be linked to the dietary fiber content of W. globosa, which enhances the product’s structural integrity and mouthfeel. Collectively, these enhancements suggest that W. globosa not only improves the nutritional profile of pasta but also contributes positively to its sensory quality, reinforcing its role as a multifunctional ingredient in food formulation.

In contrast, the inclusion of dried W. globosa in fried sweet potato balls resulted in minimal changes across most sensory attributes. Only the color score declined significantly with increased W. globosa concentration. The control sample (0 g) received the highest color rating (8.17 ± 0.58), while samples containing 1.75 g, 3.5 g, and 7 g scored 6.49 ± 0.62, 6.27 ± 0.70, and 6.13 ± 0.96, respectively. This decline may be attributed to the thermal degradation of green pigments during frying, which can lead to browning or discoloration perceived as less appealing by consumers49. Despite this, no significant differences were observed in appearance, odor, taste, texture, or overall liking, indicating that W. globosa inclusion up to 7 g does not adversely affect the sensory acceptability of the product.

The differing sensory responses between the two food matrices-boiled pasta and fried sweet potato balls-highlight the importance of processing methods in modulating the sensory impact of functional ingredients50. While boiling preserved and enhanced pigment expression in pasta, frying led to pigment degradation. Nevertheless, both product types maintained overall acceptability, demonstrating that W. globosa can be effectively incorporated into a variety of food systems.

These findings underscore the potential of W. globosa not only as a nutritional enhancer but also as a sensory-active ingredient, especially in applications where heat stability of pigments is not a critical limitation. Based on sensory and functional evaluation, 10 g and 7 g of dried W. globosa were identified as optimal enrichment levels for fresh pasta and fried sweet potato balls, respectively, providing enhanced nutritional benefits without compromising consumer acceptance.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates the impact of cultivation media on the growth and nutritional composition of W. globosa under outdoor conditions. The Chlorella medium yielded the highest biomass and protein, while the 16-16-16 medium with vitamin B complex and FeSO4 supported bioactive compound synthesis. W. globosa was microbiologically safe and rich in protein, fiber, chlorophyll, and calcium. Incorporation into pasta and fried sweet potato balls enhanced their nutritional profiles without compromising sensory quality. These results confirm its potential as a cost-effective, nutrient-dense functional food ingredient. Future studies should assess the life cycle sustainability and nutrient bioavailability in these products to optimize their functional and nutritional value.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

-

Appenroth, K. J. et al. Nutritional value of duckweeds (Lemnaceae) as human food. Food Chem. 217, 266–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.08.116 (2017).

-

Appenroth, K. J. et al. Nutritional value of the duckweed species of the genus Wolffia (Lemnaceae) as human food. Front. Chem. 6, 483. https://doi.org/10.3389/fchem.2018.00483 (2018).

-

Kawamata, Y. et al. Genotoxicity and repeated-dose toxicity evaluation of dried Wolffia globosa Mankai. Toxicol. Rep. 7, 1233–1241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxrep.2020.09.006 (2020).

-

Sirirustananun, N., Phimthong, C. & Numpet, T. Utilization of hydroponic fertilizer for watermeal cultivation and an investigation of the suitability of the fresh watermeal (Wolffia arrhiza (L.)) supplement for tilapia rearing. Egypt. J. Aquat. Biol. Fish. 26, 217–228 (2022).

-

Romano, L. E., van Loon, J. J. W. A., Vincent-Bonnieu, S. & Aronne, G. Wolffia globosa, a novel crop species for protein production in space agriculture. Sci. Rep. 14, 27979. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79109-4 (2024).

-

Baidya, S. & Patel, A. B. Effect of co-cultivation of Wolffia arrhiza (L.) on water quality parameters in a feed based semi-intensive carp culture system. J. Entomol. Zool. Stud. 6, 102–109 (2018).

-

Ahmad, M. S. et al. Bioenergy potential of Wolffia arrhiza appraised through pyrolysis, kinetics, thermodynamics parameters and TG-FTIR-MS study of the evolved gases. Bioresour. Technol. 253, 297–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2018.01.033 (2018).

-

Faizal, A., Sembada, A. A. & Priharto, N. Production of bioethanol from four species of duckweeds (Landoltia punctata, Lemna aequinoctialis, Spirodela polyrrhiza, and Wolffia arrhiza) through optimization of saccharification process and fermentation with Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 28, 294–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjbs.2020.10.002 (2021).

-

Muslykhah, U. et al. Potential use of Wolffia globosa powder supplementation on in vitro rumen fermentation characteristics, nutrient degradability, microbial population, and methane mitigation. Sci. Rep. 14, 28611. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78475-3 (2024).

-

Hu, Z. et al. Determining the nutritional value and antioxidant capacity of duckweed (Wolffia arrhiza) under artificial conditions. LWT 153, 112477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2021.112477 (2022).

-

On-Nom, N. et al. Wolffia globosa-based nutritious snack formulation with high protein and dietary fiber contents. Foods 12, 2647. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12142647 (2023).

-

Ruekaewma, N., Piyatiratitivorakul, S. & Powtongsook, S. Culture system for Wolffia globosa L. (Lemnaceae) for hygiene human food. Songklanakarin J. Sci. Technol. 37, 575–580 (2015).

-

Said, D. S., Chrismadha, T., Mayasari, N., Febrianti, D. & Suri, A. R. M. Nutrition value and growth ability of aquatic weed Wolffia globosa as alternative feed sources for aquaculture system. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 950, 012044. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/950/1/012044 (2022).

-

Dhamaratana, S., Methacanon, P. & Charoensiddhi, S. Chemical composition and in vitro digestibility of duckweed (Wolffia Globosa) and its polysaccharide and protein fractions. Food Chem. Adv. 6, 100867. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.focha.2024.100867 (2025).

-

Yadav, N. K., Patel, A. B., Debbarma, S., Priyadarshini, M. B. & Priyadarshi, H. Characterization of bioactive metabolites and antioxidant activities in solid and liquid fractions of fresh duckweed (Wolffia globosa) subjected to different cell wall rupture methods. ACS Omega 9, 19940–19955. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.3c09674 (2024).

-

Yadav, N. K. et al. Characterization of phenolic compounds in watermeal (Wolffia globosa) through LC-ESI-QTOF-MS/MS: Assessment of bioactive compounds, in vitro antioxidant and anti-diabetic activities following different drying methods. J. Food Meas. Charact. 18, 8651–8672. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11694-024-02833-y (2024).

-

Meir, A. Y. et al. Effect of green-mediterranean diet on intrahepatic fat: The DIRECT PLUS randomised controlled trial. Gut 70, 2085–2095. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2020-323106 (2021).

-

Prosridee, K. et al. Optimum aquaculture and drying conditions for Wolffia arrhiza (L.) Wimn. Heliyon. 9, e19730. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e19730 (2023).

-

Bertrand, E. M. & Allen, A. E. Influence of vitamin B auxotrophy on nitrogen metabolism in eukaryotic phytoplankton. Front. Microbiol. 3, 375. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2012.00375 (2012).

-

Fitzpatrick, T. B. & Chapman, L. M. The importance of thiamine (Vitamin B1) in plant health: From crop yield to biofortification. J. Biol. Chem. 295, 12002–12013. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.REV120.010918 (2020).

-

Ruangsomboon, S., Sornchai, P. & Prachom, N. Enhanced hydrocarbon production and improved biodiesel qualities of Botryococcus braunii KMITL 5 by vitamins thiamine, biotin and cobalamin supplementation. Algal Res. 29, 159–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.algal.2017.11.028 (2018).

-

Ruangsomboon, S. Effect of light, nutrient, cultivation time and salinity on lipid production of newly isolated strain of the green microalga, Botryococcus braunii KMITL 2. Bioresour. Technol. 109, 261–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2011.07.025 (2012).

-

Vonshak, A. & Maske, H. Algae: Growth techniques and biomass production. In Techniques in Bioproductivity and Photosynthesis (eds Coombs, J. & Hall, D. O.) 66–77 (Pergamon Press, 1982).

-

Lasfar, S., Monette, F., Millette, L. & Azzouz, A. Intrinsic growth rate: A new approach to evaluate the effects of temperature, photoperiod and phosphorus-nitrogen concentrations on duckweed growth under controlled eutrophication. Water Res. 41, 2333–2340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2007.01.059 (2007).

-

Richmond, A. Handbook of Microalgal Culture: Applied Phycology and Biotechnology (Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2013).

-

AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis of the Association of Official Analytical Chemists: Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International. (twenty-first ed., AOAC, Washington, DC, USA, 2019).

-

Becker, E. W. Microalgae Biotechnology and Microbiology (Cambridge University Press, 1994).

-

Meilgaard, M. C., Civille, G. V. & Carr, B. T. Sensory Evaluation Techniques 4th edn. (CRC Press, 2007).

-

Chen, H. & Xiong, L. Pyridoxine is required for post-embryonic root development and tolerance to osmotic and oxidative stresses. Plant J. 44, 396–408. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02538.x (2005).

-

Croft, M. T., Lawrence, A. D., Raux-Deery, E., Warren, M. J. & Smith, A. G. Algae acquire vitamin B12 through a symbiotic relationship with bacteria. Nature 438, 90–93. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature04056 (2005).

-

Tang, Y. Z., Koch, F. & Gobler, C. J. Most harmful algal bloom species are vitamin B1 and B12 auxotrophs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 20756–20761. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1009566107 (2010).

-

Wang, L. et al. B vitamins supplementation induced shifts in phytoplankton dynamics and copepod populations in a subtropical coastal area. Front. Mar. Sci. 10, 1206332. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2023.1206332 (2023).

-

Munkit, J., Nithikulworawong, N., Mapanao, R. & Jiwyam, W. Biomass production of water-meal (Wolffia globosa) and its chemical composition and amino acid profiles when grown with chemical fertilizer in an out-door polyethylene (PE) tank cultivation system. Aqua. Stud. 25, 236–244. https://doi.org/10.4194/AQUAST2439 (2025).

-

APHA, AWWA, & WEF. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater, 24th ed. (American Public Health Association, 2022).

-

Baek, G. Y., Saeed, M. & Choi, H.-K. Duckweeds: their utilization, metabolites and cultivation. Appl. Biol. Chem. 64, 73. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13765-021-00644-z (2021).

-

Tkalec, M., Munarec, J., Vidakovic-Cifrek, Z., Jelencic, B. & Regula, I. The effect of salinity and osmotic stress on duckweed Lemna minor L. Acta Bot. Croat. 60, 237–244 (2001).

-

Ullah, H., Gul, B., Khan, H. & Zeb, U. Effect of salt stress on proximate composition of duckweed (Lemna minor L.). Heliyon. 7, e07399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07399 (2021).

-

Chantiratikul, A. et al. Effect of Wolffia meal [Wolffia globosa (L.) Wimm.] as a dietary protein replacement on performance and carcass characteristics in Broilers. Int. J. Poult. Sci. 9, 664–668. https://doi.org/10.3923/ijps.2010.664.668 (2010).

-

Thor, K. Calcium-nutrient and messenger. Front Plant Sci. 10, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2019.00440 (2019).

-

U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Food safety (2024). Available at: https://www.fda.gov/food/guidance-regulation-food-and-dietary-supplements/food-safety-modernization-act-fsma

-

Maiani, G. et al. Carotenoids: Actual knowledge on food sources, intakes, stability and bioavailability and their protective role in humans. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 53, S194–S218. https://doi.org/10.1002/mnfr.200800053 (2009).

-

Anderson, J. W. et al. Health benefits of dietary fiber. Nutr. Rev. 67, 188–205. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-4887.2009.00189.x (2009).

-

Hussain, M. et al. Biochemical and nutritional profile of maize bran-enriched flour in relation to its end-use quality. Food Sci. Nutr. 9, 3336–3345. https://doi.org/10.1002/fsn3.2323 (2021).

-

Slavin, J. Fiber and prebiotics: Mechanisms and health benefits. Nutrients 5, 1417–1435. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu5041417 (2013).

-

Stone, H. & Sidel, J. L. Sensory Evaluation Practices 3rd edn. (Elsevier Academic Press, 2004).

-

Giménez, A., Ares, G. & Gámbaro, A. Survival analysis to estimate sensory shelf life using acceptability scores. J. Sens. Stud. 23, 571–582. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-459X.2008.00173.x (2008).

-

Zhu, S. C. et al. A comparative study on the taste quality of Mytilus coruscus under different shucking treatments. Food Chem. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2023.135480 (2023).

-

Spinnler, H.-E. Flavors from amino acids. In Food Flavors, Chemical & Functional Properties of Food Components (ed. Jelen, H.) 121–136 (CRC Press, 2011).

-

Turkmen, N., Poyrazoglu, E. S., Sari, F. & Velioglu, S. Effects of cooking methods on chlorophylls, pheophytins and colour of selected green vegetables. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 41, 281–288. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2621.2005.01061.x (2006).

-

Deliza, R. & MacFie, H. J. H. The generation of sensory expectation by external cues and its effect on sensory perception and hedonic ratings: A review. J. Sens. Stud. 11, 103–128. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-459X.1996.tb00036.x (1996).

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely acknowledge Scientific Reports for granting a full waiver of the article processing charges (APCs) associated with this publication.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sirison, J., Ruangsomboon, S., Jongput, B. et al. Cultivation of Wolffia globosa and its application in functional food development. Sci Rep 15, 38255 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22032-z

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22032-z