Introduction

Hand, Foot and Mouth Disease (HFMD) is an infectious disease caused by one or more enteroviruses. Its primary modes of transmission include contact and gastrointestinal spread, with cases occurring year-round with a higher prevalence in the summer and fall seasons. The disease predominantly affects infants and young children1. Pathogenic serotypes of enteroviruses responsible for HFMD include the coxsackievirus A and B groups, along with certain serotypes of echo viruses and enterovirus A71 (EVA71)2. In recent years, following the widespread implementation of the EVA71 vaccine, many regions have observed an increasing trend of HFMD cases caused by coxsackievirus A6 (CVA6) and CVA16. In particular, CVA6 has emerged as a primary pathogen in certain areas3. CVA6 primarily infects young children4and has been reported to be more likely to induce atypical HFMD5. Its hallmark presentation is the development of various rashes, extending beyond typical HFMD locations to include the face and other areas of the body. Although most cases are nonlethal, CVA6 infection often results in more extensive skin damage than EVA71 and CVA16, with the condition being self-limiting in nature6. Among the structural proteins of CVA6, VP1 stands out as a typical structural protein that features critical sites on its surface to recognize and bond to host cells. These sites may contribute to the pathogenicity and environmental adaptability of CVA67,8. To understand the dynamics of HFMD in Jinhua City, Zhejiang Province, enhance disease testing and prevention efforts, and on this basis reduce the incidence of HFMD, we conducted a molecular epidemiological investigation of CVA6 strains circulating in the local community from 2019 to 2023.

Results

Epidemiology of CVA6 associated with HFMD in Jinhua City between 2019 and 2023

A total of 57,944 clinical cases of HFMD were reported in Jinhua City, Zhejiang Province, between 2019 and 2023. The average annual incidence rate of HFMD was 193.7 per 100,000 people (range 89.97–231.92); the incidence rate decreased from 2019 to 2020, increased from 2020 to 2021, then decreased again from 2021 to 2022 and finally incidence from 2022 to 2023 (Table 1). Among these HFMD cases, 34,032 were males and 23,912 were females. The men accounted for 58. 73% (34,032/57,944) and women for 41. 27% (23,912/57,944). The samples were taken from patients mainly between the ages of 1 and 5 years of age. Most of the cases were under 3 years of age (66.29%).

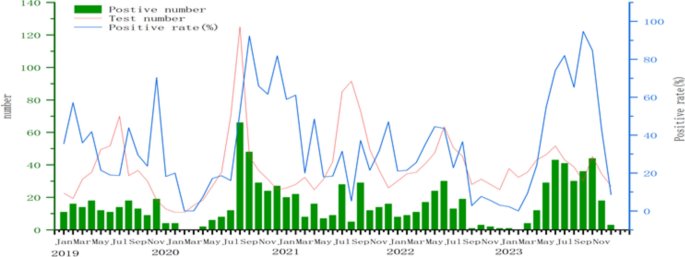

A total of 2850 throat samples were collected from patients with HFMD and used for HEV virus detection during 2019 to 2023. Among them, 1,689 cases tested positive via PCR, resulting in a positive rate of 59.26%. Specifically, EVA71 accounted for 1.01% (17/1689), CVA16 for 22.02% (372/1689), CVA6 for 53.17% (898/1689), and CVA10 for 4.56% (77/1,689). Apart from these four viruses, other enteroviruses constituted 19.24% (325/1689) of the cases.The rate of HEV detection in 2021 (66.1%) was the highest in the years from 2019 to 2023, while the rate of CVA6 detected in 2020 (42.3%) was the highest. Notably, the number of CVA6-positive cases surpassed that of all other strains during the same period, establishing itself as the predominant strain (Table 1). Analyzing the monthly data for CVA6 from 2019 to 2023, positive cases and detection rates were predominantly concentrated from April to October. Over the 5 year span, there were two periods of low activity and one notable peak. From September 2022 to April 2023, both testing numbers and positivity rates were relatively subdued, with an observable increase post-May. The peak in testing quantity and positive cases occurred in July and August 2020, significantly surpassing the corresponding figures in the other three years (Fig. 1).

Epidemiology of CVA6 associated with HFMD in Jinhua City between 2019 and 2023

A total of 57,944 clinical cases of HFMD were reported in Jinhua City, Zhejiang Province during 2019 to 2023. The average annual HFMD incidence rate was 193.7 per 100,000 population (range: 89.97 to 231.92); the incidence rate decreased from 2019 to 2020, and increased from 2020 to 2021, then decreased again from 2021 to 2022 and finally incidence from 2022 to 2023. Among these HFMD cases, 34,032 were males and 23,912 were females. Males accounted for 58.73% (34,032/57,944) while females accounted for 41.27% (23,912/57,944). Samples were from patients mainly between the ages of under 1 and 5 years old. Most cases were under 3-years-old (66.29%) (Table 1). A total of 2,850 throat samples were collected from patients with HFMD and used for HEV virus detection during 2019 to 2023. Among them, 1,689 cases tested positive via PCR, resulting in a positive rate of 59.26%. Specifically, EVA71 accounted for 1.01% (17/1,689), CVA16 for 22.02% (372/1,689), CVA6 for 53.17% (898/1,689), and CVA10 for 4.56% (77/1,689). Apart from these four viruses, other enteroviruses constituted 19.24% (325/1,689) of the cases.The rate of HEV detection in 2021 (66.1%) was the highest in the years from 2019 to 2023, while the rate of CVA6 detected in 2020 (42.3%) was the highest. Notably, the number of CVA6-positive cases surpassed that of all other strains during the same period, establishing itself as the predominant strain (Table 1). Analyzing the monthly data for CVA6 from 2019 to 2023, positive cases and detection rates were predominantly concentrated from April to October. Over the 5 year span, there were two periods of low activity and one notable peak. From September 2022 to April 2023, both testing numbers and positivity rates were relatively subdued, with an observable increase post-May. The peak in testing quantity and positive cases occurred in July and August 2020, significantly surpassing the corresponding figures in the other three years (Fig. 1).

Amplification of full-length CVA6 VP1 sequences

Forty CVA6-positive samples with viral loads >1 (times) (10^5) copies/µL after genotyping were randomly selected for each year. Amplification was conducted using a one-step RT-qPCR method, and after validation through 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis, the product sizes were approximately 1,220 bp. Sequencing results produced full-length VP1 segments for all 200 samples, each measuring 915 bp and encoding 305 amino acids.

Analysis of nucleotide and amino acid homology in CVA6 VP1

Nucleotide homology among the 200 isolated CVA6 strains in Jinhua City ranged from 95.4% to 100%, while the amino acid homology ranged from 98.4% to 100%. Comparative analysis with selected reference strains from GenBank suggested that in comparison to that of the reference strain A (Gdula, AY421764.1 prototype), the nucleotide homology for the predominant circulating CVA6 strain in Jinhua City ranged from 82.5% to 83.5%, while the amino acid homology ranged from 95.4% to 95.7%. Compared with the first reported CVA6 strain (JQ364886) in China, the nucleotide homology of the VP1 gene was 82.5% to 83.8%, and the amino acid homology was 96.1% to 97.0%. Compared with CVA6 (the earliest D3 subtype reference strain KM114057) isolated in Finland in 2008, the nucleotide homology of the VP1 gene was 90.7% to 91.6%, and the amino acid homology was 98.4% to 99.3%.

Analysis of amino acid mutations in CVA6 VP1

The VP1 gene of prevalent CVA6 strains consisted of 915 nucleotides, encoding 305 amino acids. In comparison to that in the Gdula prototype strain, among the 200 prevalent CVA6 strains, 19 amino acid sites underwent substitutions, namely T5S, D6 N, V8I, S10 N, A14 T, T32S, N97S, L98Q, I103 V, S137 N, S160G, V174I, T194S, T255 A, L261 F, A268 V, T279S, T287S, and S305 F.

Evolutionary tree analysis of CVA6 VP1

Construction of a phylogenetic tree based on the nucleotide sequences of the VP1 coding region of 200 CVA6 strains isolated in Jinhua and the nucleotide sequences of the VP1 coding region of CVA6 strains from around the world. According to Song et al.9, CVA6 VP1 can be categorized into four genotypes, namely A, B, C, and D. The prototype strain of Gdula isolated in the United States in 1949 is located in genotype A; genotype B includes the Shandong strain isolated in China in 1992 and three Guangdong strains isolated in China in 2004, 2005, and 2007; genotype C consists of only two strains, including the Shandong strain isolated in China in 1996 and the Indian strain in 2008; the strains isolated in Japan, the United States, the United Kingdom, Finland, France, Australia, Spain, Thailand, and China (Beijing, Guangdong, Zhejiang, Jiangsu, Shandong, Jiangxi, Henan, Yunnan, Shanxi, Heilongjiang, and Changchun) since 1999 collectively constitute genotype D. The strains isolated since 1999 in Japan, the United States, the United Kingdom, Finland, France, Australia, Spain, Thailand, and China (Zhejiang, Henan, Beijing, Guangdong, Jiangsu, Shandong, Jiangxi, Yunnan, Shanxi, Heilongjiang, and Changchun) together comprise genotype D. Genotype D can be further categorized into three subgenotypes. Genotype D can be further categorized into three subtypes: D1-D3. subtype D1 was found in Taiwan of China (2007), Japan (1999), France (2010), Spain (2008) and Australia (2006). subtype D2 was prevalent in Japan and China from 2006 to 2013. after 2008, subtypes D3 were found in Finland, the United Kingdom, China and Japan. subtype. Evolutionary analyses have shown that the D3 subtype can be divided into two branches, D3 a and D3b. The D3b branch is composed of the D3 subtype that is found in Finland (Finland). Branch D3b consisted of strains isolated in Finland (2008), China (2010-2015), Japan (2016-2017) and the United Kingdom (2015). Branch D3a consisted of strains isolated in China and Thailand (2019) including the present study (Fig. 2).

Discussion

The clinical manifestations of HFMD are complex and diverse; in addition to asymptomatic occult infection, there may be mild HFMD with fever and rash or herpes on the hands, feet, mouth cavity and other parts as the main features, or it can be complicated by encephalitis. Severe HFMD with clinical symptoms such as pulmonary edema, respiratory failure due to encephalitis or meningitis, respiratory infections, and myocarditis may lead to death2. The prevalence of novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) affected the incidence rate of HFMD severely10. Intensive interventions facilitated the control of HFMD with self-quarantine, social distancing, wearing face masks, and frequent hand hygiene, which may explain the lower incidence in 2020 and 2022. There is a seasonal trend in the prevalence of CVA6, with a higher incidence in spring and summer (Fig. 1). Strengthen seasonal surveillance by activating an enhanced surveillance system before the epidemic season, focusing on places where children gather, such as schools and childcare centers; use historical data and mathematical models to predict the peak time and scale of the epidemic season, and deploy preventive and control measures in advance; dynamically adjust the key areas for monitoring and allocation of resources by analyzing real-time data; and set up sentinel surveillance stations in high-prevalence areas to regularly collect samples for viral testing and monitor the virus mutation and transmission trends.

The causative agents in HFMD encompass over 20 different types, and there is no cross-immunity evoked between these diverse pathogens. Different types of enteroviruses can result in recurrent infections in children11. The nucleic acid testing results of 1,689 HFMD cases in Jinhua City from 2019 to 2023 revealed that CVA6 exhibited the highest positive rate at 53.17%, followed by CVA16 at 22.02%, whereas EVA71 had the lowest positive rate at 1.01%. CVA6 has emerged as the dominant circulating strain in the local population. CVA6 is prone to recombination and mutation, which not only alters the clinical symptoms of HFMD but through the accumulated nucleotide mutations may also significantly enhance the pathogenicity of newly mutated strains, leading to outbreaks and epidemics of HFMD12. Therefore, conducting genetic characterization of CVA6 in the laboratory is crucial.

Studies have shown that CVA6 strain which broke out in Finland in 2008 was not only a new genetic variant, but also the main pathogen leading to HFMD outbreaks in Asia, Europe and America. Through genetic recombination, a new CVA6 subgenotype was produced which led to the outbreak of HFMD in these areas13 By analyzing VP1 gene sequence of CVA6 epidemic strains in China in 2010, Japanese and Spanish strains in 2011 and Finland CVA6 mutant strains in 2008, it was found that their nucleotide homology exceeds 90%. It was further confirmed that the CVA6 epidemic strain in the world in recent years was the same genetic variation recombinant strain.According to the phylogenetic tree, it can be seen that the evolution of CVA6 in China can be roughly divided into three stages. Before 2011, D1 and D2 subgenotype was the main prevalent type. From 2011 to 2013, D2 and D3 subgenotype were prevalent together, and D3 subgenotype gradually increased. Since 2014, D3 subgenotype has become the dominant prevalent type.Through the homology and phylogenetic analysis of VP1 gene sequences, it was found that the VP1 gene sequences of CVA6 strains which popular around the world in recent years were significantly different from Gdula prototype strain. All CVA6 isolates in Jinhua belonged to the D3 subtype. Compared with the Gdula prototype strain, the nucleotide homology of the VP 1 gene was 82.5% to 83.5%, and the amino acid homology was 95.4% to 95.7%. Compared with the first reported CVA 6 strain in China, the nucleotide homology of VP1 gene was 82.5% to 83.8%, and the amino acid homology was 96.1% to 97.0%. The results showed that the gene sequences of CVA 6 epidemic strains in Jinhua region had changed significantly during the evolutionary process.

Research indicates that when the nucleotide sequence difference for the entire VP1 region is (le) 15%, it is considered to represent the same genotype, and when the difference rate is (le)8%, it is considered the same gene subtype14. In this study, the similarity between the full nucleotide sequences of the 200 CVA6 VP1 strains ranged from 95.4% to 100%, with a difference rate of 0.00–4.6% (difference rate < 8%). The results of systematic evolutionary tree analysis showed that the prevalent CVA6 strains causing HFMD in Jinhua City from 2019 to 2023 belonged to the D3 subtype, specifically the D3a evolutionary branch. These strains are closely related to isolates from Shanghai, Zhejiang, Yunnan, Beijing, and other regions. It can therefore be inferred that multiple transmission chains exist in the circulation of CVA6 in Jinhua City. CVA6 in the local community is co-evolving with CVA6 strains from other provinces in mainland China, indicating the co-circulation of multiple CVA6 transmission chains in Jinhua City.

Compared to that of the prototype strain Gdula, the VP1 region of the 200 prevalent CVA6 strains in Jinhua City exhibited 19 amino acid mutations sites. Research by Fan et al.15revealed that D3 strains display different trends in amino acid variations at six sites, namely 5, 30, 137, 174, 242, and 283. Vietnam witnessed amino acid variations A5 T, V30 A, S173 N, and I242 V during 2011-2015, while Japan observed A5 T and V30 A variations16. These findings suggest that different regions, climates, and populations may be the main factors contributing to variations at these six amino acid sites. In Jinhua City, two variations, namely S173 N and V174I, were identified at these six sites. In a study by Wang et al.17, lethal strains in a CVA6-induced mouse model were associated with variations at sites 5 T, 30 A, and 137 N. Among the 200 prevalent strains in Jinhua City, 190 strains exhibited variations at 5 T and 137 N, and the number of strains with the specific mutation showed an increasing trend over the years. These findings suggest that prevalent CVA6 strains in Jinhua City may be evolving toward increased virulence, which could be a contributing factor to the rising proportion of CVA6 cases in the local community. Strengthen the surveillance of CVA6 infection, especially in childcare centers, to detect cases and trace the chain of transmission in a timely manner; raise public awareness and educate the public about the transmission route, symptoms and preventive measures of CVA6 through the media, schools and community activities; and the mutation of the VP1 locus provides a reference for vaccine development.

The limitations of our study were as follows: First, owing to the impact of COVID-19, the numbers of HFMD cases and specimens in the past 3 years were limited. Second, detailed analysis result of the relationship between the genotypes identified in this study and the clinical course of the disease need to be addressed in future research. Continuous and comprehensive surveillance for CVA6 and other HFMDassociated HEV is needed to better understand and evaluate the prevalence and evolution of the corresponding pathogens.

Materials and methods

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the Centre for Disease Control and Prevention, Jinhua, Zhejiang, China (2023-03).Written informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Sample collection

In adherence to the HFMD monitoring plan in Zhejiang Province, a minimum of five throat swab specimens from HFMD cases reported at comprehensive medical facilities in nine counties (cities, districts) within Jinhua City were collected on a monthly basis. These samples were subsequently dispatched to the local Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in their respective counties (cities, districts) for HFMD enterovirus nucleic acid detection. Positive samples were further scrutinized at the municipal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for validation. A total of 2,850 specimens from HFMD cases in Jinhua City between 2019 and 2023 was collected through the HFMD monitoring system.

Instruments and reagents

Viral DNA/RNA extraction kits were procured from Xi’an Tianlong Science and Technology Co., Ltd., while the CVA6 enterovirus nucleic acid detection kit was sourced from Mabsky Biotech Co., Ltd. The PrimeScriptTM One-Step reverse transcriptase qPCR (RT-qPCR) kit, agarose, and DNA markers were acquired from TaKaRa (Japan). Experimental equipment included an automated nucleic acid extractor from Xi’an Tianlong Science and Technology Co., Ltd., an ABI7500 fluorescent quantitative PCR system manufactured by Applied Biosystems, USA.

Amplification of complete CVA6 VP1 nucleotide sequences

For individuals testing positive for CVA6 through RT-qPCR and gene sequencing, the entire VP1 sequence underwent RT-qPCR amplification. The upstream primer used was (5′)-TGTGCVAAGGACVACYGAYGAG-(3′), and the downstream primer was (5′)-AGATGYCGGTTTACCVACTCT-(3′)18. The RT-qPCR test was performed using the Access Quick RT-qPCR kit (Promega, USA). The details of the RT-qPCR program are as follows: (42,^{circ })C for 30 min, (95,^{circ })C for 15 min; (94,^{circ })C for 30 s, (45,^{circ })C for 30 s, and (68,^{circ })C for 50 s, for a total of 40 cycles, followed by a final extension at (68,^{circ })C for 10 min. All 200 virus samples were successfully amplified, generating products with a length of approximately 1,200 bp.

Gene sequencing and characterization of enteroviruses

The specific PCR products, validated via agarose gel electrophoresis, were purified before being sent for bidirectional sequencing by Shanghai BioGerm Co., Ltd. Analysis of nucleotide and amino acid homology along with amino acid site mutations for the 200 strains obtained in this study was performed using the Megalign module of DNAstar v.8.1.319software. Subsequently, applying the Distance function of MEGA1120 software, we employed the Kimura 2-parameter model to determine the average genetic distances among samples of the VP1 sequences of prevalent and prototype strains of enteroviruses. Additionally, utilizing the Phylogeny function, the Neighbor-joining method with a Bootstrap value of 1,000 was employed to align VP1 sequences from prevalent enterovirus strains with those from other regions in GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nucleotide/). An evolutionary tree of the VP1 gene was subsequently constructed on this basis. This tree was then exported in the “nwk” format and uploaded to the Interactive Tree of Life website (https://itol.embl.de/) for refinement.

Number of positive cases, number of tests, and positive rates of CVA6 per month between 2019 and 2023.

Number of positive cases, number of tests, and positive rates of CVA6 per month between 2019 and 2023. Note: Strains highlighted in a bold black font indicate the prevalent CVA6 strains in Jinhua City analyzed in this study.

Data availibility

The sequence data supporting the results of this study have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information, gene entry number: PP280529-PP280548, PQ740707 – PQ740886.

References

-

Huang, S.-W., Cheng, D. & Wang, J.-R. Enterovirus a71: virulence, antigenicity, and genetic evolution over the years. J. Biomed. Sci. 26, 81 (2019).

-

Li, X.-W. et al. Chinese guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of hand, foot and mouth disease (2018 edition). World Journal of Pediatrics 14, 437–447 (2018).

-

Pourianfar, H. R. & Grollo, L. Development of antiviral agents toward enterovirus 71 infection. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 48, 1–8 (2015).

-

Mirand, A. et al. Outbreak of hand, foot and mouth disease/herpangina associated with coxsackievirus a6 and a10 infections in 2010, france: a large citywide, prospective observational study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 18, E110–E118 (2012).

-

Cai, Y. et al. Active immunization with a coxsackievirus a16 experimental inactivated vaccine induces neutralizing antibodies and protects mice against lethal infection. Vaccine 31, 2215–2221 (2013).

-

Ogino, M. & Ogino, T. 5’-phospho-rna acceptor specificity of gdp polyribonucleotidyltransferase of vesicular stomatitis virus in mrna capping. J. Virol. 91, 10–1128 (2017).

-

Shi, J., Huang, X., Liu, Q. & Huang, Z. Identification of conserved neutralizing linear epitopes within the vp1 protein of coxsackievirus a16. Vaccine 31, 2130–2136 (2013).

-

Campanella, M. et al. The coxsackievirus 2b protein suppresses apoptotic host cell responses by manipulating intracellular ca2+ homeostasis. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 18440–18450 (2004).

-

Song, Y. et al. Persistent circulation of coxsackievirus a6 of genotype d3 in mainland of china between 2008 and 2015. Sci. Rep. 7, 5491 (2017).

-

Wang, X. et al. Analysis of the pathogen spectrum of hand, foot and mouth disease and the genetic characteristics of coxsackievirus a6 in pingshan district, shenzhen, 2019. Chin. Front. Health Quarantine 43, 264–268 (2020).

-

Wang, J. et al. Genomic surveillance of coxsackievirus a10 reveals genetic features and recent appearance of genogroup d in shanghai, china, 2016–2020. Virol. Sin. 37, 177–186 (2022).

-

Wan-xue, Z. & Jue, L. Research progress on the epidemiology of hand, foot and mouth disease caused by coxsackievirus a6. Zhonghua Jibing Kongzhi Zazhi 25, 605–611 (2021).

-

Puenpa, J. et al. Molecular epidemiology and the evolution of human coxsackievirus a6. J. Gen. Virol. 97, 3225–3231 (2016).

-

Yun-yan, F., Song-feng, O. & Min-mei, C. Molecular epidemiological characterization for vp1 region gene of coxsackievirus a6 in china. Zhonghua Jibing Kongzhi Zazhi 24, 934–938 (2020).

-

Anh, N. T. et al. Emerging coxsackievirus a6 causing hand, foot and mouth disease, vietnam. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 24, 654 (2018).

-

Yoshitomi, H. et al. Molecular epidemiology of coxsackievirus a6 derived from hand, foot, and mouth disease in fukuoka between 2013 and 2017. J. Med. Virol. 90, 1712–1719 (2018).

-

Wang, S.-H. et al. Divergent pathogenic properties of circulating coxsackievirus a6 associated with emerging hand, foot, and mouth disease. J. Virol. 92, 10–1128 (2018).

-

Zeng, H. et al. The epidemiological study of coxsackievirus a6 revealing hand, foot and mouth disease epidemic patterns in guangdong, china. Sci. Rep. 5, 10550 (2015).

-

Burland, T. G. Dnastar’s lasergene sequence analysis software. Bioinf. Methods Protocols 71–91 (1999).

-

Tamura, K., Stecher, G. & Kumar, S. Mega11: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38, 3022–3027 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank all the staff and leaders of Jinhua City CDC for their support. This work was supported by the Jinhua Science and Technology Project (grant no. 2023-4-174).

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, P., Pang, Z., Zhang, B. et al. Molecular epidemiological characteristics of coxsackievirus A6 in Jinhua, China, 2019–2023. Sci Rep 15, 26459 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99469-9

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

Version of record:

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99469-9