Introduction

The environmental pollution is a major concern for human health, leading to the spread of various diseases such as cancer, asthma, and multiple birth defects1. The increasing concerns about the world pollution mainly due to the industrialization, domestic wastewater and agrochemicals, have stimulated the efforts to develop new, simple and efficient methods for the removal of pollutants from the air, soil and water2. Moreover, regarding the significant limitations of water resources, the wastewater treatment and recycling is of great consideration toward the supplying of water demands3. In this context, different methods such as advanced oxidation processes, reverse osmosis, adsorption, ion exchange, ozonation, precipitation, filtration, and coagulation, have been used to treat the industrial wastewaters4.

Owing to the inefficiency and limitations of the traditional methods, development of the new alternative methods is essential for the effective water remediation. The nano-scale materials have received significant attention for this purpose, due to their high surface area and reactivity, significant adsorption capacity, and prominent catalytic activity5. The interesting properties of nanomaterials led to the rapid development of nano-based methods for environmental remediation and the emergence of environmental nanotechnology6. Different nanoparticles (NPs) including metals, micelles, dendrimers, and nanotubes, have been used for the removal of various organic and inorganic contaminations from water7.

Among these NPs, iron oxide NPs (IONPs) have found a wide range of applications, due to their unique advantages, including the availability of various methods for their facile and large-scale synthesis, high magnetic activity, biocompatibility, and easy functionalization8,9,10. IONPs also display the significant and stable catalytic activity, comparable to the natural enzymes, with various applications11. The high absorption capacity of IONPs12 as well as their prominent catalytic activity have considered greatly for water remediation and wastewater treatment7,13. The peroxidase-like activity is one of the prominent catalytic properties of IONPs that is mainly responsible for oxidation of various substances in the presence of H2O214. It has been found that the nanozyme activity of IONPs is significantly influenced by their size, shape and surface chemistry15. The hydroxyl radicals produced in the IONPs-mediated Fenton-like reactions are able to attack various organic compounds and convert them into the smaller molecules with less toxicity15,16,17. Therefore, IONPs are considered as a potent candidate for the removal of water pollutants such as pesticides, herbicides, antibiotics, organic dyes, etc.

The biogenic synthesis of NPs has attracted great attention among different methods reported for the large-scale synthesis of high colloidal NPs with the controlled sizes and shapes18. The outstanding advantages of the green synthesis methods, such as the cost-effectiveness, environmental friendliness, and the superior physicochemical properties of synthesized NPs, led to their extensive applications specially in the biomedical and the environmental fields19,20. The surface functionalization of NPs by the extracted organic compounds from the microorganisms or plants not only improves the physicochemical properties of NPs, but also create the new biological properties such as antimicrobial and anticancer activities21.

To evaluate the potential of biogenic method for synthesis of IONPs with the superior properties, in this study, the functionalized IONPs (FIONPs) with the ethanolic extract of Betula pendula were synthesized using the solvothermal method. This species contains high amount of triterpenoids, specially betulinic acid with the well-known antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant activities. The resulted FIONPs were fully characterized for their physicochemical properties. Then, the potential biological properties of FIONPs, including the peroxidase activity, biocompatibility, and antibacterial effects as well as their ability for the removal of different pollutants including the chlorpyrifos (CHP) pesticide, cefixime antibiotic, and the commonly used dyes of methylene blue (MB) and crystal violet (CV) from water were studied (Scheme 1).

Schematic illustration of FIONPs synthesis and investigation of their biocompatibility, antibacterial activity, and ability for the pollutant’s removal from water.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

RPMI1640 medium, trypsin-EDTA solution, fetal bovine serum (FBS), trypsin-EDTA solution, and antibiotic (penicillin-streptomycin) solution were purchased from Gibco (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY). 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)−2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT), and the microbial culture media of Luria–Bertani (LB) broth, Mueller Hinton agar (MHA) and Blood agar were purchased from Sigma (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany). The organic dyes of MB and CV, acetic acid (HAc), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2, 30%), FeCl3.6H2O (≥ 98%), sodium acetate (NaAc, 99.0%), ethylene glycol (≥ 99.5%), 3,3’,5,5’-Tetramethylbenzidine (TMB), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, 99.7%), methanol (99.9%), acetonitrile (99.9%), n-Hexane (≥ 97.0%), and ethanol (99.9%) were purchased from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). Technical grade CHP (97%) was donated by the Golshimi Sepahan Co. (Isfahan, Iran). Cefixime (≥ 98.0%) was obtained as a gift from Farabi pharmaceutical Co. (Isfahan, Iran). The bark samples of B. pendula were obtained from the national botanical garden of Iran (Tehran, Iran).

Green synthesis of FIONPs

The plant extract was first prepared from the bark samples of B. pendula, based on the previously reported procedure22. For this purpose, the plant samples were first washed carefully with the distilled water and dried in an oven at 60 °C, overnight. The plant extraction was prepared by addition of 1 g powdered samples into 20 mL of ethanol, following by the periodic stirring and sonication at 10-min intervals for 3 h. The plant debris was then separated by the centrifugation at 2000 rpm for 10 min and filtration using Whatman filter paper (No. 1) and the final extract was freeze-dried and stored at −20 °C for the subsequent use.

FIONPs were synthesized using the solvothermal method, based on the previous report23 by modification (Scheme S1). Briefly, 1.25 g FeCl3.6H2O and 3.6 g NaAc were completely dissolved in 40 mL ethylene glycol under stirring. Subsequently, 200 mg of the powdered extract was added into the solution and stirred for 10 min. The reaction mixture was then added into a Teflon-lined autoclave, sealed and heated at 180 °C for 8 h. The resulted FIONPs were separated magnetically, washed once with the absolute ethanol and three times with the distilled water and dried in an oven at 50 °C, overnight.

Characterization of FIONPs

The size and shape of IONPs and FIONPs were studied using a field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM, Quanta 200, USA) while their elemental composition was determined by X-ray energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS, Silicon drift detectors, Germany). The crystal structure of FIONPs was studied using the X-ray diffraction (XRD, D-8 Advance powder X-ray diffractometer, Bruker, Germany) with the Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å). The surface functional groups of IONPs and FIONPs were determined by Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy (FTIR 6300, Jasco, Japan) in the wavenumber range of 4000 to 400 cm−1. The magnetic activity of IONPs and FIONPs was measured using a vibration sample magnetometer (VSM; Lake Shore Model 7400, Japan). The average hydrodynamic size and size distribution as well as the zeta potential value of FIONPs were studied by a ZEN 3600 Zetasizer (Malvern, Worcestershire, UK). The thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) of FIONPs was carried out under the nitrogen atmosphere in the temperature range of 50 °C to 600 °C and a heating rate of 10 °C min−1 by using a Mettler TG50 instrument (Schwerzenbach, Switzerland).

The peroxidase-like activity measurement

The potential catalytic activity of FIONPs was investigated for oxidation of the chromogenic substrate (TMB) in the presence of 1 M H2O2, based on the previously reported method24. To this aim, different concentrations of FIONPs (5, 10, and 40 µg mL−1) and TMB (0, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, and 2.5 mM) were used in HAc/NaAc buffer (pH 3.6), and the absorbance was measured at 652 nm using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Cary 100, Agilent, USA). The peroxidase-like activity of FIONPs was then calculated based on the following equation:

$$:C=frac{V}{left(epsilon times:lright)}times:left(frac{varDelta:A}{varDelta:T}right):$$

Where C is the peroxidase-like activity of FIONPs in units, V is the reaction volume (mL), ε is the molar absorbance coefficient of TMB (39000 M−1 cm−1 at 652 nm), l is the cuvette length (1 cm), and (:frac{varDelta:A}{varDelta:T}) is the absorbance change of TMB per min at 652 nm. The specific activity was also calculated based on the following equation:

$$:S=frac{C}{M}=frac{frac{V}{left(epsilon times:lright)}times:left(frac{varDelta:A}{varDelta:T}right):}{M}$$

Where S is the specific activity of FIONPs (U mg−1) and M is the concentration of NPs (mg).

Batch experiments

A series of batch experiments was conducted to evaluate the ability of FIONPs for remediation of MB and CV dyes, CHP pesticide, and cefixime antibiotic from water. All the dye removal experiments were carried out in the final volume of 20 mL in HAc/NaAc buffer (pH 3.6) under shaking at 250 rpm at 25 °C, based on the previous reports with some modifications21,25,26. The concentration of FIONPs and dyes was 4 mg L−1 while 0.5 M H2O2 was used in each reaction. The degradation of dyes was monitored at the constant intervals over 72 h using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Agilent, Cary 100) at 664 nm for MB and 585 nm for CV.

All the pesticide removal experiments were carried out in the methanol solution (20% v/v, 50 mL, pH 3.6) under UV illumination and shaking at 250 rpm, based on the previous report with some modifications27. The concentration of FIONPs and CHP was 100 mg L−1 while 0.5 M H2O2 was used in each reaction. The degradation of CHP was monitored at the constant intervals over 8 h at the detection wavelength of 299 nm using a high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC, KNAUER Azura, Germany) equipped with a Kromasil C18 column (250 mm × 4.6 mm). The mobile phase consisted of isocratic (at the constant concentration) methanol/water (88:12 v/v) with the flow rate of 1 mL min−1.

The degraded products of CHP were also detected using Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (LC–MS) analysis, based on the previous report with some modifications27. An ultra-fast liquid chromatography (UFLC, Shimadzu, Japan) coupled with a high-resolution hybrid quadrupole mass spectrometer (Sciex 3200 QTRAP, Toronto, Canada) was used for this purpose. The degradation products were separated using a Kromasil 100-5-C18 column (150 mm × 4.6 mm) under the mobile phase of 0.3% formic acid in water (A) and methanol (B) at a constant flow rate of 300 µL min−1 at 30 °C. The linear gradient began with 90% A for 2 min, decreased to 10% A in 1 min and continued in this condition for 23 min before returning to the initial condition (90% A) in 1 min, and continued in this condition for 8 min. Mass spectrometry analysis was performed in the range of m/z = 100–400 with the ion source parameters of ion source gas I 40 psi, ion source gas II 40 psi, curtain gas 35 psi, temperature 500 °C, capillary voltage − 4.5 KV, declustering potential − 10 V and injection volume of 15 µL.

The antibiotic removal experiments were conducted in a final volume of 100 mL (pH 3.6) under the sonication in an ultrasonic bath, based on the previous report with some modifications2. The concentration of FIONPs and cefixime was 100 mg L−1 while 0.5 M H2O2 was added into each reaction. The degradation was monitored at constant intervals over 60 h at the detection wavelength of 299 nm using a HPLC instrument (KNAUER Azura, Germany) equipped with a reverse-phase column (Kromasil C18, 250 mm × 4.6 mm). The mobile phase was isocratic (at constant concentration) methanol/water (88:12 v/v) with the flow rate of 1 mL min−1.

In vitro cell studies

MTT assay was used to evaluate the potential cytotoxic effects of IONPs and FIONPs and the products of CHP degradation on the human fibroblast (HF), U87 human brain glioma and MCF-7 human breast cancer cells, according to the previous report28. For this purpose, 200 µL of RPMI medium containing 104 cells was added into each well of a 96-well plate and incubated at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator, overnight. Then, different concentrations of the samples (50, 100 and 200 µg mL−1 in media) were added into the individual wells and the cells were incubated at the same condition for 48 h. The medium was then removed from the wells and replaced with 100 µL MTT solution (0.5 mg mL−1 in media). After incubation for 4 h at the same condition, the medium was carefully removed again from the wells and the precipitated formazan crystals were dissolved in 100 µL DMSO. The absorbance of the wells was measured at 570 nm and the cells viability was calculated as the absorbance ratio of each treatment and the control.

The potential antibacterial activity of FIONPs was also investigated by different assays of agar disk diffusion, minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC), according to the guidelines of the Institute of Clinical and Laboratory Standards29. For agar disk diffusion assay, the single colonies of S. aureus (ATCC25923) and E. coli (ATCC25922) were first inoculated into the LB broth medium and incubated overnight at 30 °C and 37 °C, respectively. Then, the 0.5 McFarland bacterial suspension was prepared from the overnight cultures and inoculated onto the MHA plates. Subsequently, the impregnated filter paper discs with 25 µg of FIONPs or the reference antibiotics (amoxicillin for S. aureus and gentamicin for E. coli) were embedded on the cultured plates and incubated for 24 h at the same condition before measurement of the inhibition zones. The same concentration of pure extract of B. pendula was also used as negative control. For the MIC assay, a serial dilution of 20 to 2 × 103 µg mL−1 FIONPs in the sterile deionized water was first prepared. Then, 100 µL of each dilution and 100 µL of 0.5 McFarland bacterial suspension were added into each well of 96-well microtiter plate and incubated at the aforementioned condition for 18 h. Subsequently, the bacterial growth was investigated by measuring of the absorbance of the wells at 630 nm using an Agilent 800TS microplate reader. MIC is assigned as the lowest concentration of FIONPs without the significant absorbance at 630 nm. MBC is assigned as the lowest concentration of FIONPs for the completely inhibition of bacterial growth that was determined by the inoculation of the MIC and neighboring wells on the blood agar plates and incubation for 18 h at the aforementioned condition. Amoxicillin was also used in the MIC/MBC assays as the clinical standards.

Statistical analyses

All the experiments were carried out in triplicate and the results were expressed as the mean value of three independent experiments ± standard deviation. Student’s t-test (Microsoft Excel, Microsoft Corporation, USA) was used to analyze the data and P values of less than 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

Results and discussion

Synthesis and characterization of FIONPs

The green synthesis approach of IONPs has considered great attention for the biomedical applications, due to the using of biological compounds and non-toxic solvents instead of the commonly used toxic chemicals30,31. Additionally, the green synthesis of IONPs, may lead to the emergence of novel and valuable properties such as catalytic, antioxidant or antimicrobial activities in the resulted FIONPs32. The adsorption or chemical bonding of biomolecules onto the NPs surface can also inhibit their agglomeration33,34.

The versatility and efficiency of solvothermal method could also be employed for the extensive synthesis of hydrophilic and superparamagnetic IONPs with the controlled size and shape. The solvothermal reaction in temperatures above the boiling point of solvent and high pressures, leads to the decomposition of iron (III) chloride hexahydrate (FeCl₃·6 H₂O) as the common precursor. Ethylene glycol is usually served as the solvent and reducing agent in the solvothermal reaction. The addition of sodium acetate not only induces the hydrolysis of iron ions but also improved the electrostatic stability of IONPs35. The interaction of FeCl3 with NaOAc leads to the formation of Fe (OAc)3 as an intermediate that is subsequently transferred to IONPs after reduction by ethylene glycol. The using of capping agents and surfactants also affects the morphology and dispersity of IONPs36.

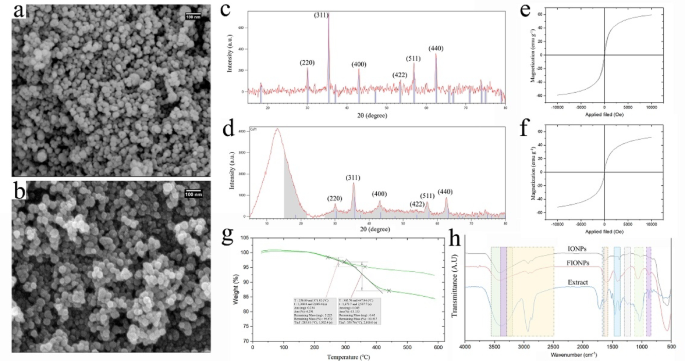

The results of physicochemical characterization of IONPs and FIONPs are presented in Fig. 1. The FE-SEM images (Fig. 1a-b) clearly show the significant effect of the extracted compounds on the size and morphology of FIONPs. The use of B. pendula extract led to the synthesis of highly monodispersed NPs with more uniform size and shape than the uncoated IONPs. The particle size distribution histograms of IONPs and FIONPs were presented in Fig. S1 and S2, respectively. Based on the results, the using of plant extract led to the synthesis of FIONPs with the smaller sizes and limited size distribution. The size of IONPs was distributed over a wider range with the highest abundance in the size range of 30–60 nm. While FIONPs mainly represented the spherical shape with the size range of 20–40 nm. The plant organic compounds seem to affect the initial nucleation and subsequent growth of IONPs as well as their agglomeration, leading to the smaller sizes and narrow size distribution of FIONPs. The results of DLS analysis also confirmed that the synthesized FIONPs are monodisperse and colloidal representing an average hydrodynamic size of 118.4 nm with PDI of 0.52 and zeta potential value of −28.4. The results are in accordance with the reported results by Mahajan et al.36, regarding the narrow size distribution of magnetic γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles prepared in the presence of SDS, as a capping reagent. The EDS elemental analysis of FIONPs (Fig. S3) showed the presence of Fe, O, C, N, P, S, and Cl elements with the weight percentages of 78.77, 11.43, 4.05, 2.89, 1.85, 0.94, and 0.07%, respectively. The presence of N, P, S, and Cl elements could be attributed to the surface coating of FIONPs and confirmed their successful functionalization with the organic compounds of B. pendula extract. The XRD patterns of IONPs and FIONPs (Fig. 1c-d, respectively) show the same characteristic peaks at the 2θ values of 30.3°, 35.55°, 43.35°, 53.85°, 57.4° and 62.95°, corresponding to the crystallographic planes of (220), (311), (400), (422), (511) and (440), in the cubic crystal structure of Fe3O437 and clearly confirm the successful synthesis of magnetite NPs. The broad peak with 2θ value of below 20° in the XRD pattern of FIONPs is attributed to the characteristic reflection of carbon atoms originated from the plant organic compounds38. This low-angle peak also confirms the presence of a significant organic layer with the amorphous nature on the surface of FIONPs. The same position of the characteristic peaks of the diffraction patterns of IONPs and FIONPs indicate that the crystalline structure of NPs is not affected by the functionalization of IONPs while the decreased intensity of the peaks in the diffraction patterns of FIONPs is attributed to the amorphous coating of the plant extract37. VSM analysis revealed that the magnetic activity of IONPs was affected by the functionalization with the plant extract such that the saturation magnetization values of 51.77 and 45.3 emu g−1 obtained for IONPs and FIONPs, respectively (Fig. 1e-f). However, this effect was not considerable and the hysteresis curve of FIONPs also represents a prominent magnetic activity similar to IONPs. TGA curves of IONPs and FIONPs (Fig. 1g) reveal a weight loss of up to 7.6 wt% for IONPs after increasing of the temperature to 550 °C while a significantly higher weight loss of up to 19.5 wt% is observed for FIONPs at the same condition. The results of TGA analysis also clearly show the effective surface coating of FIONPs with the organic compounds. Based on the results, about 11.9% of the total weight of FIONPs could be attributed to the plant organic compounds that is consistent with the significant XRD peak originated from the organic layer on the surface of FIONPs. FTIR analysis (Fig. 1h) also revealed different functional groups on the surface of IONPs and FIONPs, including O–H stretching (3400 cm−1), sp-C–H stretching of alkynes (3241 cm−1), sp3-C–H stretching of alkanes (2925 cm−1), C = C stretching of alkenes (1608 cm−1), C–O–C stretching vibrations of oligosaccharides (1499 cm−1), C–O stretching of alcohols (1050 cm−1), C–H stretching of aromatics (845 cm−1), and Fe–O stretching (575 cm−1)39,40. The comparison of FTIR spectra of FIONPs and B. pendula extract also showed the similar peaks, including N = O stretching of nitro groups (1383.7 cm−1) and C–N stretching of aromatic and aliphatic amines (1246.7 cm−1), which can further confirm the surface coating of FIONPs with the plant extract, in accordance with the results of FE-SEM, TGA and EDS analysis.

FE-SEM images (a and b), XRD patterns (c and d), VSM curves (e and f), TGA graphs (g) and FTIR spectra (h) of IONPs and FIONPs, respectively.

Nanozyme activity

Different catalytic activities of IONPs, specially their peroxidase activity, were reported previously14,41,42. The enzyme activity of IONPs has also been reported to depends on their size, shape, and composition43. The surface chemistry of IONPs also represents the significant effects on their catalytic activity43. Since the use of plant extract affected the physicochemical properties and surface chemistry of the synthesized nanoparticles, the potential peroxidase activity of IONPs and FIONPs was also investigated by using TMB, as a substrate. The results (Fig. 2) clearly showed the concentration-dependent activity of IONPs and FIONPs for the TMB oxidation. Interestingly, FIONPs represented the higher peroxidase-like activity compared to IONPs. The specific activity of 0.50 ± 0.02 mmol min−1 mg−1 obtained for FIONPs that is approximately 1.79 times higher than the specific activity of IONPs (0.28 ± 0.01 mmol min−1 mg−1), at the same condition. Surface functionalization of IONPs with plant-extracted organic compounds not only improves their colloidal stability and reduces their agglomeration, but may also improve their catalytic activity. The presence of an organic layer on the surface of IONPs can enhance the substrate adsorption to the surfaces or accelerate electron transfer, which ultimately leads to the increased peroxidase activity and efficient removal of organic pollutants44. The surface modification has been suggested recently to solve the common constraints of low catalytic activity, substrate selectivity and permeability of nanozymes45. The results also indicate that the peroxidase-like behavior of IONPs and FIONPs follows the Michaelis-Menten kinetics (Fig. 2). The peroxidase-like activity of FIONPs is useful for the H2O2-mediated generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the subsequent removal of organic pollutants from water46.

The peroxidase-like activity of IONPs and FIONPs. The Michaelis-Menten curves for different concentrations of TMB and the calculated Km and Vmax (left). The absorption spectra at 652 nm over time for different concentrations of FIONPs (right).

Batch experiments

The potential application of FIONPs for the water remediation was evaluated on three groups of common hazardous chemicals including dyes, pesticides, and antibiotics.

The organic and synthetic dyes, are considered among the most important environmental contaminants with the large-scale production and use for different industrial applications47. MB is a tricyclic phenothiazine derivative with the widespread use as an organic dye in the textile, chemical and pharmaceutical industries26. CV is a synthetic triarylmethane with the main use in the large-scale production of painting and printing inks. However, the significant toxic effects of these dyes on the environment and the human health is a serious problem48. CV is high toxic and tumorigenic for mammalian cells and aquacultures that remains in soil and water for long time, due to its resistance to the natural degradation. Therefore, the potential of FIONPs for the removal of MB and CV was also evaluated in this study.

All the batch experiments were conducted by using 4 mg L−1 of dyes and FIONPs. The results showed more than 99% reduction in the CV concentration after 48 h treatment with FIONPs (Fig. 3a) while the MB removal was slower such that more than 99% reduction in the concentration of MB was observed after 72 h, at the same condition (Fig. 3b). Recently, Shuka Jara et al. also reported the green synthesis of IONPs using Vernonia amygdalina plant leaf extract and efficient degradation of CV (97.47%) and MB (94.22%)49. This color reduction can occur through the decomposition of organic dyes via the Fenton reaction in the presence of H2O2. The Fenton process includes the reaction of Fe2+ with H2O2 and the subsequent production of highly reactive OH radicals that finally leads to the advanced oxidation processes (AOPs)50.

Antibiotics with the well-known inhibitory and killing activities against microorganisms have found widespread applications, especially in the medicine and food industry. However, there are significant concerns about their side-effects on other organisms, due to the uncontrolled release into environment51. For example, the widespread use of a cephalosporin antibiotic, cefixime, with the poor water solubility and high chemical instability, has raised the concerns about its environmental contamination and the emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria52. Therefore, the potential removal of cefixime, as a model antibiotic, from water was investigated in the presence of FIONPs. The monitoring of cefixime concentration in the batches over time using HPLC method showed more than 98% removal of the antibiotic after 60 h (Fig. 3c). The results are comparable with the recent report of Mousavi et al. regarding 98.71% cefixime removal from wastewater using nZVI/copper slag nanocomposite52. Vasseghian et al. have also reported up to 94.19% degradation of cefixime (CFX) from an aqueous solution by using SWCNT/ZnO/Fe3O4 heterojunction composites53. The complete degradation of cefixime through the reactive species, especially short-lived OH radicals, produced by the underwater plasma bubbles has also been reported by Zhang et al.54. Based on the results, the Fenton-like oxidation in the presence of OH radicals is the most likely mechanism of CFX degradation.

Another series of experiments was conducted to evaluate the ability of FIONPs for pesticide removal. The organophosphates are one of the most important and extensively used pesticides in the modern agriculture to increase the production yield of crops55. CHP is a widely used organophosphate pesticide and also a household insecticide with the adverse effects on the reproductive capacity, endocrine glands, cardiovascular and respiratory systems56,57. CHP has been reported as an important contaminants of water58. Therefore, the ability of FIONPs for degradation of CHP under UV radiation was monitored over time by using HPLC analysis. The results showed the high potential of FIONPs for the photodegradation of CHP, such that more than 98% of the initial pesticide was degraded after 8 h (Fig. 3d). The results are comparable with those obtained recently by using TiO2 NPs59, g-C3N5/CdS dendrite/AgNPs60, and nanocomposites of TiO2 and ZnO supported on the superparamagnetic IONPs61. Recently, Bouzidi et al. have also been reported the efficient (74.96%) adsorption of an organophosphate insecticide, acephate, using chitosan incorporated magnetite62.

UV-Vis spectra of CV (a) and MB (b) solutions and HPLC spectra of cefixime (c) and CHP (d) solutions after treatment with FIONPs for different time intervals.

CHP degradation mainly resulted in three fragments that were isolated by HPLC and further studied by using LC-MS analysis. Comparison of the mass spectra of these degradation products (Fig. 4) with the previous report61, revealed that chlorpyrifos oxon (CPO), 3,5,6-trichloro-2-pyridinol (TCP), and diethyl phosphate (DEP) are the main products of CHP degradation with the charge-to-mass ratio of 334, 196, and 154, respectively. Based on the LC-MS results, the proposed mechanism of CHP degradation includes its reaction with OH radicals to produce CPO and the subsequent hydrolysis to DEP and TCP. This mechanism is similar to the recently proposed mechanism for the photodegradation of CHP60,61. Two different pathways can be proposed for degradation of CHP, based on the results and literature. In the first pathway, the heterocyclic ring of CHP undergoes hydroxyl substitution on the C(1), C(3), and C(6) atoms, following by the Fe-mediated oxidative attack to the P = S bond and formation of the P = O bond. In the second pathway, the Fe- or •OH-mediated oxidation of P = S bond occurred before three transformation processes that finally lead to the cleavage and separation of the phosphorus backbone from the nitrogen heterocyclic ring. The kinetic studies also revealed that the FIONPs-mediated removal of examined contaminants including MB, CV, cefixime and CHP follow the Michaelis-Menten kinetics and are fitted to the pseudo-first-order model (Fig. S4).

LC-MS spectrum of CHP and its degradation derivatives using FIONPs (a). The degradation pathway of CHP and the chemical structure of its derivatives (b).

In vitro cell studies

Although the biocompatibility of magnetite NPs have been well-known, the surface functionalization with the organic compounds may affect the biological activity of these NPs, specially their biocompatibility24. Therefore, the potential cytotoxicity of IONPs and FIONPs was also studied on the HF, MCF-7 and U87 cells, in vitro. The results (Fig. S5-7) clearly showed the high biocompatibility of FIONPs such that 90.41 ± 2.33, 95.11 ± 1.54, and 95.83 ± 2.16 of the HF, MCF-7 and U87 cells, respectively, were viable after 48 h exposure with 200 µg mL−1 FIONPs. These results indicate that the functionalization of IONPs with the B. pendula extract has no adverse effects on the biocompatibility of NPs.

The well-known inhibitory effect of CHP on the acetylcholinesterase (AChE) leads to the accumulation of acetylcholine (ACh) in the synaptic cleft and subsequent overstimulation of neurons and finally, a range of fatal neurological symptoms63. Therefore, investigation of the potential toxicity and harmful effects of remained CHP and its degraded compounds is very important64. The in vitro studies on U87 human brain glioma cells showed the high cytotoxicity of CHP such that only 8.58% cell viability was observed after the exposure with 200 µg L−1 CHP, while the cell viability of 12.54, 17.7, and 56.77% obtained for CPO, TCP, and DEP, respectively (Fig. 5a).

The antimicrobial activity of B. pendula extract have also been reported, recently65,66. This could be attributed to the high content of polyphenols and flavonoids in the B. pendula leaf extract that has been clarified based on the LC-MS analysis, recently67. Therefore, FIONPs may possess the antimicrobial activity due to the presence of B. pendula extracted biomolecules on their surface. The subsequent in vitro studies confirmed this hypothesis and revealed the significant antibacterial effect of FIONPs on S. aureus and E. coli strains. Interestingly, FIONPs displayed higher antibacterial effects on S. aureus with the growth inhibition zones of 27 ± 1.9, 32 ± 2.6, and 10 ± 1.2 mm for IONPs, FIONPs, and amoxicillin, respectively. The growth inhibition zones of 13 ± 0.9, 18 ± 1.4, and 26 ± 1.9 mm also obtained for E. coli following the exposure with IONPs, FIONPs, and gentamicin, respectively (Fig. 5b). In the same condition, the growth inhibition zones of 28.1 ± 0.9 and 32.95 ± 1.3 mm also obtained following the exposure of E. coli and S. aureus, respectively, with the same amount (25 µg) of B. pendula extract. The results confirmed the significant antibacterial activity of B. pendula leaf extract. However, the surface coating of IONPs with the B. pendula extract led to the comparable antibacterial effects by using lower concentrations of the extract and facilitated its application. The antibacterial potential of NPs was further studied by the MIC and MBC assays. The results (Table S1), in consistent with the results of disk diffusion assay, showed the higher antibacterial activity of FIONPs in comparison with IONPs. Moreover, FIONPs displayed the increased activity on Gram-positive S. aureus bacteria than Gram-negative E. coli strain. The antibacterial activity of FIONPs was comparable with the antibacterial activity of amoxicillin, as the clinical standard (Table S1). Similar results have also been reported recently for the green synthesized IONPs by the clove and green coffee extracts32. A comprehensive review on the antibacterial properties of the green synthesized IONPs has also been reported by Ghazzy et al., recently11.

The in vitro studies of U87 cells viability after exposure with the degraded products of CHP (a) and the antibacterial activity of IONPs and FIONPs against S. aureus and E. coli strains.

Conclusion

The growing concerns about the water scarcity and the increasing of waters pollution and wastewaters have made it necessary to develop the new and efficient methods to remove the water pollutants. The high biocompatibility, adsorption capacity and enzymatic activity of IONPs, especially green synthesized IONPs, have attracted great attention for this purpose. Our results confirmed the high potential of FIONPs as a promising agent for the efficient removal of a wide range of common water contaminants including dyes, antibiotics, and pesticides. The surface functionalization of IONPs with the organic compounds of B. pendula extract not only improved their physicochemical properties but also increased their enzymatic activity and potential for the pollutant’s removal. Moreover, the resulted FIONPs represented the significant antibacterial activity that is another advantage of FIONPs for the water and wastewater remediation.

However, there are significant limitations to the use of IONPs in water remediation that still need to be addressed. There are significant limitations in terms of the scale of nanoparticle synthesis for widespread application that still need to be overcome. Despite all the advances in the methods of IONPs synthesis, there are still challenges in terms of the scalability of IONPs synthesis and its cost for widespread application. Although the solvothermal method is relatively easier and more efficient than other conventional methods of IONPs synthesis such as the coprecipitation method, there are currently limitations in the scale of synthesis and equipment cost. Further studies are also needed to improve the catalytic activity, long-term stability and reusability of IONPs. In the case of peroxidase activity of IONPs, the need to use hydrogen peroxide is a major limitation in widespread applications. The dependence of the peroxidase activity of nanoparticles on the presence of hydrogen peroxide is also a major limitation for widespread applications that has not yet been resolved.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information file).

Abbreviations

- CHP:

-

Chlorpyrifos

- CPO:

-

Chlorpyrifos oxon

- CV:

-

Crystal violet

- DEP:

-

Diethyl phosphate

- DLS:

-

Dynamic light scattering

- DMSO:

-

Dimethyl sulfoxide

- EDS:

-

Energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy

- FBS:

-

Fetal bovine serum

- FE-SEM:

-

Field emission scanning electron microscopy

- FIONPs:

-

Functionalized iron oxide nanoparticles

- FTIR:

-

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy

- HAc:

-

Acetic acid

- HF:

-

Human fibroblast

- HPLC:

-

High Performance Liquid Chromatography

- IONPs:

-

Iron oxide nanoparticles

- LB:

-

Luria–Bertani

- LC–MS:

-

Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry

- MB:

-

Methylene blue

- MBC:

-

Minimum bactericidal concentration

- MHA:

-

Mueller Hinton agar

- MIC:

-

Minimum inhibitory concentration

- MTT:

-

3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)−2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- NaAc:

-

Sodium acetate

- NPs:

-

Nanoparticles

- PDI:

-

Polydispersity index

- RPMI:

-

Roswell park memorial institute

- ROS:

-

Reactive oxygen species

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- TCP:

-

3,5,6-trichloro-2-pyridinol

- TGA:

-

Thermogravimetric analysis

- TMB:

-

3,3’,5,5’-Tetramethylbenzidine

- UV-Vis:

-

Ultraviolet-visible

- VSM:

-

Vibration sample magnetometer

- XRD:

-

X-ray diffraction

References

-

Ambaye, T. G., Vaccari, M., Hullebusch, E. D., Amrane, A. & Rtimi, S. Mechanisms and adsorption capacities of Biochar for the removal of organic and inorganic pollutants from industrial wastewater. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 18, 3273–3294 (2021).

-

Vaz-Ramos, J. et al. Magnetic few-layer graphene nanocomposites for the highly efficient removal of benzo(a)pyrene from water. Environ. Sci. Nano. 10, 1660–1675 (2023).

-

Liaquat, S. et al. Fabrication of Fe3O4 based cellulose acetate mixed matrix membranes for As(iii) removal from wastewater. Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol. 10, 1637–1652 (2024).

-

Siddiqua, A., Hahladakis, J. N. & Al-Attiya, W. A. K.A. An overview of the environmental pollution and health effects associated with waste landfilling and open dumping. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 29, 58514–58536 (2022).

-

Roy, A., Sharma, A., Yadav, S., Jule, L. T. & Krishnaraj, R. Nanomaterials for remediation of environmental pollutants. Bioinorg. Chem. Appl. 2021, 1764647 (2021).

-

Chahar, M. et al. Recent advances in the effective removal of hazardous pollutants from wastewater by using nanomaterials—A review. Front. Environ. Sci. 11, 1–24 (2023).

-

Mondal, P. et al. Sustainable application of nanoparticles in wastewater treatment: Fate, current trend & paradigm shift. Environ. Res. 232, 116071 (2023).

-

El-Bahr, S. M. et al. Biosynthesized iron oxide nanoparticles from petroselinum crispum leaf extract mitigate lead-acetate-induced anemia in male albino rats: Hematological, biochemical and histopathological features. Toxics 9, 123 (2021).

-

Saif, S., Tahir, A., Asim, T., Chen, Y. & Adil, S. F. Polymeric nanocomposites of iron–oxide nanoparticles synthesized using terminalia chebula leaf extract for enhanced adsorption of arsenic(v) from water. Colloids Interfaces. 3, 17 (2019).

-

Kucharczyk, K. et al. Hyperthermia treatment of cancer cells by the application of targeted silk/iron oxide composite spheres. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 120, 111654 (2021).

-

Ghazzy, A. et al. Al hunaiti, A. Magnetic iron oxide-based nanozymes: from synthesis to application. Nanoscale Adv. 6, 1611–1642 (2024).

-

Singh, D., Sillu, D., Kumar, A. & Agnihotri, S. Dual nanozyme characteristics of iron oxide nanoparticles alleviate salinity stress and promote the growth of an agroforestry tree,: Eucalyptus Tereticornis Sm. Environ. Sci. Nano. 8, 1308–1325 (2021).

-

Xiao, M., Li, N. & Lv, S. Iron oxide magnetic nanoparticles exhibiting zymolyase-like lytic activity. Chem. Eng. J. 394, 125000 (2020).

-

Yang, Y. C., Wang, Y. T. & Tseng, W. L. Amplified Peroxidase-Like activity in iron oxide nanoparticles using adenosine monophosphate: application to urinary protein sensing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 9, 10069–10077 (2017).

-

He, Y. et al. Magnetoresponsive nanozyme: magnetic stimulation on the nanozyme activity of iron oxide nanoparticles. Sci. China Life Sci. 65, 184–192 (2022).

-

Crist, E., Mora, C. & Engelman, R. The interaction of human population, food production, and biodiversity protection. Science 264, 260–264 (2017).

-

Tudi, M. et al. Agriculture development, pesticide application and its impact on the environment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 18, 1–24 (2021).

-

Jeevanandam, J. et al. Green approaches for the synthesis of metal and metal oxide nanoparticles using microbial and plant extracts. Nanoscale 14, 2534–2571 (2022).

-

Schröfel, A. et al. Applications of biosynthesized metallic nanoparticles – A review. Acta Biomater. 10, 4023–4042 (2014).

-

Pouresmaeili, A., Abbasi Kajani, A. & Davoudi, Y. Bevacizumab-targeted porous casein-coated Cobalt ferrite nanoparticles: A potent theranostic agent for Sunitinib delivery, VEGF trapping, and MRI. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 255, 114887 (2025).

-

Abbasi Kajani, A. & Bordbar, A. K. Biogenic magnetite nanoparticles: A potent and environmentally benign agent for efficient removal of Azo dyes and phenolic contaminants from water. J. Hazard. Mater. 366, 268–274 (2019).

-

Zhao, G., Yan, W. & Cao, D. Simultaneous determination of betulin and betulinic acid in white Birch bark using RP-HPLC. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 43, 959–962 (2007).

-

Gao, L. et al. Intrinsic peroxidase-like activity of ferromagnetic nanoparticles. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2, 577–583 (2007).

-

Abbasi Kajani, A., Pouresmaeili, A. & Kamali, M. Facile one-pot synthesis of the mesoporous chitosan-coated Cobalt ferrite nanozyme as an antibacterial and MRI contrast agent. RSC Adv. 14, 16801–16808 (2024).

-

Jiang, B. et al. Standardized assays for determining the catalytic activity and kinetics of peroxidase-like nanozymes. Nat. Protoc. 13, 1506–1520 (2018).

-

Cui, Y. et al. Biomimetic anchoring of Fe3O4 onto Ti3C2MXene for highly efficient removal of organic dyes by Fenton reaction. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 8, 104369 (2020).

-

Liu, H. et al. Oxidative degradation of Chlorpyrifos using ferrate(VI): kinetics and reaction mechanism. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 170, 259–266 (2019).

-

Abbasi Kajani, A., Bordbar, A. K., Zarkesh-Esfahani, S. H., Razmjou, A. & Hou, J. Gold/silver decorated magnetic nanostructures as theranostic agents: Synthesis, characterization and in-vitro study. J. Mol. Liq. 247, 238–245 (2017).

-

Lii, G. Y., Garlich, J. D. & Rock, G. C. Protein and energy utilization by the insect, argyrotaenia velutinana (walker) fed diets containing graded levels of an amino acid mixture. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. – Part. Physiol. 52, 615–618 (1975).

-

Chormey, D. S. et al. Biogenic synthesis of novel nanomaterials and their applications. Nanoscale 15, 19423–19447 (2023).

-

Priya, N., Kaur, K. & Sidhu, A. K. Green synthesis: an Eco-friendly route for the synthesis of iron oxide nanoparticles. Front. Nanotechnol. 3, 655062 (2021).

-

Mohamed, A. et al. Green synthesis and characterization of iron oxide nanoparticles for the removal of heavy metals (Cd2+ and Ni2+) from aqueous solutions with antimicrobial investigation. Sci. Rep. 13, 1–30 (2023).

-

Hufschmid, R., Teeman, E., Mehdi, B. L. & Krishnan, K. M. Browning, N. D. Observing the colloidal stability of iron oxide nanoparticles: In situ. Nanoscale 11, 13098–13107 (2019).

-

Abarca-Cabrera, L., Fraga-García, P. & Berensmeier, S. Bio-nano interactions: binding proteins, polysaccharides, lipids and nucleic acids onto magnetic nanoparticles. Biomater. Res. 25, 1–18 (2021).

-

Belew, A. A. & Assege, M. A. Solvothermal synthesis of metal oxide nanoparticles: A review of applications, challenges, and future perspectives. Results Chem. 16, 102438 (2025).

-

Mahajan, R., Suriyanarayanan, S. & Nicholls, I. A. Improved solvothermal synthesis of γ-Fe2O3 magnetic nanoparticles for SiO2 coating. Nanomaterials 11 (2021).

-

Peréz, D. L. et al. Synthesis of superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles coated with polyethylene glycol as potential drug carriers for cancer treatment. J. Nanoparticle Res. 26, 1–15 (2024).

-

Xiang, H. et al. Fe3O4@c nanoparticles synthesized by in situ solid-phase method for removal of methylene blue. Nanomaterials 11, 1–20 (2021).

-

Abbasi Kajani, A. et al. Green and facile synthesis of highly photoluminescent multicolor carbon nanocrystals for cancer therapy and imaging. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 1, 1458–1467 (2018).

-

Nam, P. H. et al. Physical characterization and heating efficacy of chitosan-coated Cobalt ferrite nanoparticles for hyperthermia application. Phys. E Low-Dimensional Syst. Nanostruct. 134, 114862 (2021).

-

Liu, X. et al. Peroxidase-Like activity of smart nanomaterials and their advanced application in colorimetric glucose biosensors. Small 15, 1–27 (2019).

-

Raineri, M. et al. Effects of biological buffer solutions on the peroxidase-like catalytic activity of Fe3O4 nanoparticles. Nanoscale 11, 18393–18406 (2019).

-

Wu, J. et al. Nanomaterials with enzyme-like characteristics (nanozymes): Next-generation artificial enzymes (II). Chem. Soc. Rev. 48, 1004–1076 (2019).

-

TratnyekP.G. et al. Reactivity of zerovalent metals in aquatic media: effects of organic surface coatings. ACS Symp. Ser. 1071, 381–406 (2011).

-

Chen, X. & Willner, I. Surface-Modified nanozymes for enhanced and selective catalysis. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 17, 44011–44029 (2025).

-

Liu, Y. et al. The peroxidase-like cleaning strategy for organic fouling of water treatment membranes based on MoS2 functional layers. J. Water Process. Eng. 54, 103955 (2023).

-

Tkaczyk, A., Mitrowska, K. & Posyniak, A. Synthetic organic dyes as contaminants of the aquatic environment and their implications for ecosystems: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 717, 137222 (2020).

-

Yang, P. et al. Effective removal of methylene blue and crystal Violet by low-cost biomass derived from eucalyptus: Characterization, experiments, and mechanism investigation. Environ. Technol. Innov. 33, 103459 (2024).

-

Jara, Y. S., Mekiso, T. T. & Washe, A. P. Highly efficient catalytic degradation of organic dyes using iron nanoparticles synthesized with Vernonia amygdalina leaf extract. Sci. Rep. 14, 1–18 (2024).

-

Xu, X. R., Li, H., Bin, Wang, W. H. & Gu, J. D. Degradation of dyes in aqueous solutions by the Fenton process. Chemosphere 57, 595–600 (2004).

-

Kovalakova, P. et al. Occurrence and toxicity of antibiotics in the aquatic environment: A review. Chemosphere 251, 126351 (2020).

-

Moridi, A. et al. Removal of cefixime from wastewater using a Superb nZVI/Copper slag nanocomposite: optimization and characterization. Water 15, 1819 (2023).

-

Erim, B., Ciğeroğlu, Z., Şahin, S. & Vasseghian, Y. Photocatalytic degradation of cefixime in aqueous solutions using functionalized SWCNT/ZnO/Fe3O4 under UV-A irradiation. Chemosphere 291, 132929 (2022).

-

Zhang, T. et al. Degradation of cefixime antibiotic in water by atmospheric plasma bubbles: Performance, degradation pathways and toxicity evaluation. Chem. Eng. J. 421, 127730 (2021).

-

Abbasi-Jorjandi, M. et al. Pesticide exposure and related health problems among family members of farmworkers in Southeast Iran. A case-control study. Environ. Pollut. 267, 115424 (2020).

-

Sereshti, H. et al. Isolation of organophosphate pesticides from water using gold nanoparticles doped magnetic three-dimensional graphene oxide. Chemosphere 320 (2023).

-

Ubaid ur Rahman, H., Asghar, W., Nazir, W., Sandhu, M. A. & Ahmed, A. Khalid, N. A comprehensive review on Chlorpyrifos toxicity with special reference to endocrine disruption: evidence of mechanisms, exposures and mitigation strategies. Sci. Total Environ. 755, 142649 (2021).

-

Huang, X., Cui, H. & Duan, W. Ecotoxicity of Chlorpyrifos to aquatic organisms: A review. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 200, 110731 (2020).

-

Farner Budarz, J. et al. Chlorpyrifos degradation via photoreactive TiO2 nanoparticles: assessing the impact of a multi-component degradation scenario. J Hazard. Mater 61–68 (2019).

-

Teymourinia, H., Alshamsi, H. A., Al-nayili, A. & Gholami, M. Photocatalytic degradation of Chlorpyrifos using ag nanoparticles-doped g-C3N5 decorated with dendritic cds. Chemosphere 344, 140325 (2023).

-

Herrera, W. et al. The catalytic role of superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles as a support material for TiO2 and ZnO on Chlorpyrifos photodegradation in an aqueous solution. Nanomaterials 14, 299 (2024).

-

Bouzidi, M. et al. Efficient removal of organophosphate insecticide employing magnetic chitosan-derivatives. International J. Biol. Macromol. 279 (2024).

-

Greer, J. B. et al. Effects of Chlorpyrifos on cholinesterase and Serine lipase activities and lipid metabolism in brains of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Toxicol. Sci. 172, 146–154 (2019).

-

Ruomeng, B. et al. Degradation strategies of pesticide residue: from chemicals to synthetic biology. Synth. Syst. Biotechnol. 8, 302–313 (2023).

-

Blondeau, D. et al. Antimicrobial activity and chemical composition of white Birch (Betula papyrifera Marshall) bark extracts. Microbiologyopen 9, 1–23 (2020).

-

Emrich, S., Schuster, A., Schnabel, T. & Oostingh, G. J. Antimicrobial activity and Wound-Healing capacity of Birch, Beech and larch bark extracts. Molecules 27, 1–15 (2022).

-

Sevastre-Berghian, A. C. et al. Betula pendula leaf extract targets the interplay between brain oxidative stress, inflammation, and NFkB pathways in amyloid Aβ1-42-treated rats. Antioxidants 12, 2110 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The financial support of the Research Council of University of Isfahan is gratefully acknowledged.

Funding

This work was supported by the Research Council of University of Isfahan.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All the experiments were approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Isfahan (Approval ID: IR.UI.REC.1403.010). All the experiments were also performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pouresmaeili, A., Kajani, A.A. Biogenic synthesis of magnetic nanozymes with peroxidase-like activity for water remediation. Sci Rep 15, 38646 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22455-8

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

Version of record:

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22455-8