Data availability

The sequencing data of primary screens, IVT mRNAs and mutagenesis libraries that support the findings of this study are available from Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14789418 and https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15041853)55,61. The raw data of Nanopore DRS from this study are available from the Korea BioData Station under accession number KAP241592 and processed data are available from figshare (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29614520 and https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17077445)62,63. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

-

Mu, X. et al. An origin of the immunogenicity of in vitro transcribed RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, 5239–5249 (2018).

-

Mu, X. & Hur, S. Immunogenicity of in vitro-transcribed RNA. Acc. Chem. Res. 54, 4012–4023 (2021).

-

Baiersdörfer, M. et al. A facile method for the removal of dsRNA contaminant from in vitro-transcribed mRNA. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 15, 26–35 (2019).

-

Moradian, H. et al. Chemical modification of uridine modulates mRNA-mediated proinflammatory and antiviral response in primary human macrophages. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 27, 854–869 (2022).

-

Cottrell, K. A. et al. The competitive landscape of the dsRNA world. Mol. Cell 84, 107–119 (2024).

-

Pindel, A. & Sadler, A. The role of protein kinase R in the interferon response. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 31, 59–70 (2011).

-

Kim, M. et al. Exogenous RNA surveillance by proton-sensing TRIM25. Science 388, eads4539 (2025).

-

Bérouti, M. et al. Pseudouridine RNA avoids immune detection through impaired endolysosomal processing and TLR engagement. Cell 188, 4880–4895 (2025).

-

Park, J. et al. Short poly(A) tails are protected from deadenylation by the LARP1–PABP complex. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 30, 330–338 (2023).

-

Eisen, T. J. et al. The dynamics of cytoplasmic mRNA metabolism. Mol. Cell 77, 786–799 (2020).

-

Lim, J. et al. Uridylation by TUT4 and TUT7 marks mRNA for degradation. Cell 159, 1365–1376 (2014).

-

Norbury, C. J. Cytoplasmic RNA: a case of the tail wagging the dog. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 14, 643–653 (2013).

-

Decker, C. J. & Parker, R. A turnover pathway for both stable and unstable mRNAs in yeast: evidence for a requirement for deadenylation. Genes Dev. 7, 1632–1643 (1993).

-

Passmore, L. A. & Coller, J. Roles of mRNA poly(A) tails in regulation of eukaryotic gene expression. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 23, 93–106 (2022).

-

Yu, S. & Kim, V. N. A tale of non-canonical tails: gene regulation by post-transcriptional RNA tailing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 21, 542–556 (2020).

-

Warkocki, Z., Liudkovska, V., Gewartowska, O., Mroczek, S. & Dziembowski, A. Terminal nucleotidyl transferases (TENTs) in mammalian RNA metabolism. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 373, 20180162 (2018).

-

Lim, J. et al. Mixed tailing by TENT4A and TENT4B shields mRNA from rapid deadenylation. Science 361, 701–704 (2018).

-

Kim, D. et al. Viral hijacking of the TENT4–ZCCHC14 complex protects viral RNAs via mixed tailing. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 27, 581–588 (2020).

-

Seo, J. J. et al. Functional viromic screens uncover regulatory RNA elements. Cell 186, 3291–3306 (2023).

-

Li, Y. et al. The ZCCHC14/TENT4 complex is required for hepatitis A virus RNA synthesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2204511119 (2022).

-

Mueller, H. et al. PAPD5/7 are host factors that are required for Hepatitis B virus RNA stabilization. Hepatology 69, 1398–1411 (2019).

-

Wesselhoeft, R. A., Kowalski, P. S. & Anderson, D. G. Engineering circular RNA for potent and stable translation in eukaryotic cells. Nat. Commun. 9, 2629 (2018).

-

Geall, A. J. et al. Nonviral delivery of self-amplifying RNA vaccines. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 14604–14609 (2012).

-

Koch, A. et al. Quantifying the dynamics of IRES and cap translation with single-molecule resolution in live cells. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 27, 1095–1104 (2020).

-

Bloom, K., van den Berg, F. & Arbuthnot, P. Self-amplifying RNA vaccines for infectious diseases. Gene Ther. 28, 117–129 (2021).

-

Chen, H. et al. Branched chemically modified poly(A) tails enhance the translation capacity of mRNA. Nat. Biotechnol. 43, 194–203 (2025).

-

Chen, H. et al. Chemical and topological design of multicapped mRNA and capped circular RNA to augment translation. Nat. Biotechnol. 43, 1128–1143 (2025).

-

Fukuchi, K. et al. Internal cap-initiated translation for efficient protein production from circular mRNA. Nat. Biotechnol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-025-02561-8 (2025).

-

Aditham, A. et al. Chemically modified mocRNAs for highly efficient protein expression in mammalian cells. ACS Chem. Biol. 17, 3352–3366 (2022).

-

Anhäuser, L. et al. Multiple covalent fluorescence labeling of eukaryotic mRNA at the poly(A) tail enhances translation and can be performed in living cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, e42 (2019).

-

Strzelecka, D. et al. Phosphodiester modifications in mRNA poly(A) tail prevent deadenylation without compromising protein expression. RNA 26, 1815–1837 (2020).

-

Orlandini von Niessen, A. G. et al. Improving mRNA-based therapeutic gene delivery by expression-augmenting 3′ UTRs identified by cellular library screening. Mol. Ther. 27, 824–836 (2019).

-

Leppek, K. et al. Combinatorial optimization of mRNA structure, stability, and translation for RNA-based therapeutics. Nat. Commun. 13, 1536 (2022).

-

Karikó, K. et al. Incorporation of pseudouridine into mRNA yields superior nonimmunogenic vector with increased translational capacity and biological stability. Mol. Ther. 16, 1833–1840 (2008).

-

Agarwal, V. & Kelley, D. R. The genetic and biochemical determinants of mRNA degradation rates in mammals. Genome Biol. 23, 245 (2022).

-

Wang, X. et al. Detection and characterization of a 3′ untranslated region ribonucleoprotein complex associated with human α-globin mRNA stability. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15, 1769–1777 (1995).

-

Durrant, M. G. et al. Systematic discovery of recombinases for efficient integration of large DNA sequences into the human genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 41, 488–499 (2023).

-

Sahin, U. et al. BNT162b2 vaccine induces neutralizing antibodies and poly-specific T cells in humans. Nature 595, 572–577 (2021).

-

Wayment-Steele, H. K. et al. RNA secondary structure packages evaluated and improved by high-throughput experiments. Nat. Methods 19, 1234–1242 (2022).

-

Hyrina, A. et al. A genome-wide CRISPR screen identifies ZCCHC14 as a host factor required for hepatitis B surface antigen production. Cell Rep. 29, 2970–2978 (2019).

-

Mueller, H. et al. A novel orally available small molecule that inhibits Hepatitis B virus expression. J. Hepatol. 68, 412–420 (2018).

-

Bazzini, A. A., Lee, M. T. & Giraldez, A. J. Ribosome profiling shows that miR-430 reduces translation before causing mRNA decay in zebrafish. Science 336, 233–237 (2012).

-

Gumińska, N. et al. Direct profiling of non-adenosines in poly(A) tails of endogenous and therapeutic mRNAs with Ninetails. Nat. Commun. 16, 2664 (2025).

-

Karikó, K. et al. Suppression of RNA recognition by Toll-like receptors: the impact of nucleoside modification and the evolutionary origin of RNA. Immunity 23, 165–175 (2005).

-

Li, X. et al. Generation of destabilized green fluorescent protein as a transcription reporter. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 34970–34975 (1998).

-

Xia, X. Detailed dissection and critical evaluation of the Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna mRNA vaccines. Vaccines (Basel) 9, 734 (2021).

-

Feshchenko, E. et al. Pandemic influenza vaccine: characterization of A/California/07/2009 (H1N1) recombinant hemagglutinin protein and insights into H1N1 antigen stability. BMC Biotechnol. 12, 77 (2012).

-

Zhang, H. et al. Algorithm for optimized mRNA design improves stability and immunogenicity. Nature 621, 396–403 (2023).

-

Enuka, Y. et al. Circular RNAs are long-lived and display only minimal early alterations in response to a growth factor. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, 1370–1383 (2016).

-

Kristensen, L. S. et al. The biogenesis, biology and characterization of circular RNAs. Nat. Rev. Genet. 20, 675–691 (2019).

-

Jens, M. Circular RNAs are a large class of animal RNAs with regulatory potency. Nature 495, 333–338 (2013).

-

Chen, R. et al. Engineering circular RNA for enhanced protein production. Nat. Biotechnol. 41, 262–272 (2023).

-

Lorenz, R. et al. ViennaRNA package 2.0. Algorithms Mol. Biol. 6, 26 (2011).

-

Huang, L. et al. LinearFold: linear-time approximate RNA folding by 5′-to-3′ dynamic programming and beam search. Bioinformatics 35, i295–i304 (2019).

-

Seo, J. J., Jung, S.-J., Lee, S., & Kim, V. N. Virus MPRA—primary screen. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14789418 (2025).

-

Schoenmaker, L. et al. mRNA–lipid nanoparticle COVID-19 vaccines: structure and stability. Int. J. Pharm. 601, 120586 (2021).

-

Ramanathan, M. et al. RNA–protein interaction detection in living cells. Nat. Methods 15, 207–212 (2018).

-

Gilbert, L. A. et al. CRISPR-mediated modular RNA-guided regulation of transcription in eukaryotes. Cell 154, 442–451 (2013).

-

van der Toorn, W. et al. Demultiplexing and barcode-specific adaptive sampling for nanopore direct RNA sequencing. Nat. Commun. 16, 3742 (2025).

-

Li, H. Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 34, 3094–3100 (2018).

-

Jung, S.-J., Seo, J., Lee, S., & Kim, V. N. RNA stability enhancers for durable base-modified mRNA therapeutic. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15041853 (2025).

-

Lee, S. RNA enhancers for durable base-modified mRNA therapeutics. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29614520.v2 (2025).

-

Chang, H. ChangLabSNU/Jung-2025-DRS: 09-08-2025 (version 20250908). Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17077445 (2025)

Acknowledgements

We thank members of our laboratory for the discussion and technical support, especially J. Yang for the plasmid cloning and preparation of IVT templates, M. Kim for sharing the Hire-PAT protocol and valuable comments, Y. Moon and D. Lim for sharing plasmids, Y. Pyo for sharing Jurkat cell transfection conditions, Y. Park for valuable discussion and J. A. Son for helping with fluorescence-based sorting. This work was supported by the Institute for Basic Science from the Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning of Korea (IBS-R008-D1 to S.-J.J., J.J.S., S.L., S-I.H., J.-e.L., S.L., H.C., J.-H.K., V.N.K.), BK21 Research Fellowships from the Ministry of Education of Korea (to S.L.) and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (RS-2023-00261343 to Y.L. and H.L.).

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

S.-J.J., J.J.S., S.L. and V.N.K. are coinventors on a patent application filed by the Institute for Basic Science and the SNU R&DB Foundation covering viral elements for mRNA stabilization in therapeutics.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Biotechnology thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

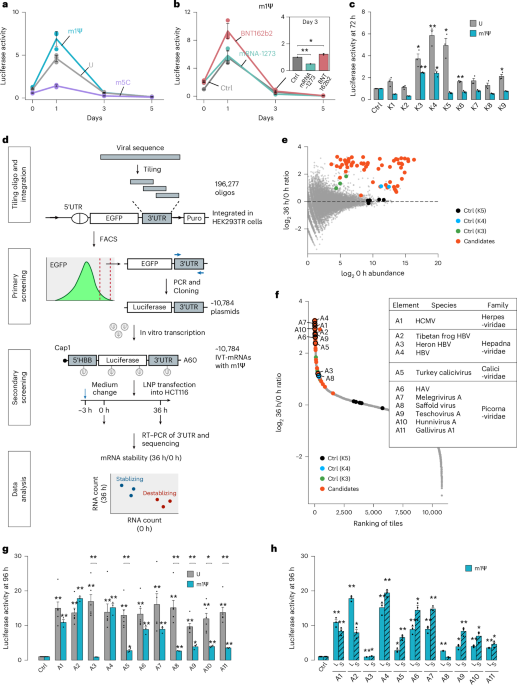

Extended Data Fig. 1 Systematic screening for viral elements that enhance m1Ψ-modified IVT mRNA.

a, Firefly luciferase signals from unmodified (U) and modified (m1Ψ, m5C) IVT mRNAs over 5 days. 10 ng of IVT mRNAs were transfected using LNP. Data were normalized to the 0-h value of unmodified mRNAs and represented as mean ± SEM (n = 3 biological replicates). b, The primary screen for m1Ψ-modified mRNAs. Genome sequences from 337 viral species were segmented into 196,277 oligos, generated by tiling 197-nt sequences with a 20-nt step size. 196,277 oligos were cloned into 3′ UTR of EGFP plasmid followed by genome integration using a pa01 integrase37. The top 0.5% of cells, based on fluorescence signal intensity, were collected by FACS. The 3′ UTR variant regions of EGFP in these sorted cells (~10,784) were PCR amplified and subsequently cloned into the 3′ UTR of a luciferase plasmid. c, Luciferase activity on Day 2 from the 3′ UTR reporter plasmids. K4m contains an inactivating mutation in the first stem of the loop. Luciferase levels from control plasmid were used for normalization. Data are represented as mean ± SEM (n = 3 biological replicates). Statistical significance was determined using a two-sided Student’s t-test, with **p < 0.01. d, Mean log2 element enrichment value of positive control elements (K4, K5) and non-functional controls (K4m, K5m) after fluorescence-based sorting. e, Spearman correlation coefficient of samples calculated using variants with UMI counts over 200 in IVT mRNA sample. f, Positive control K3 and K4 results from quadruplicates. Log2 UMI counts at 0 h (x-axis) and log2 UMI counts at 36 h (y-axis) measured by sequencing. g, A pie chart showing the distribution of tile numbers containing A-S (short constructs) elements among stabilizing tiles (adjusted p < 0.001, log2 fold change 36 h/0 h > 0.4). A-adjacent represents elements that overlap with A regions. P-values were calculated by Wald test with multiple testing adjustments. h, Identification and selection of validated candidates. For each stabilizing cluster, which refers to the contiguous tiles with stabilizing activity, we defined two elements with different lengths. The A element represents the full-length tile with the lowest p-value and a robustly predicted RNA structure. The shorter A-S element represents the core sequence shared by all tiles within the cluster. P-values were calculated by Wald test with multiple testing adjustments.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Deep mutagenesis analyses reveal key structural and sequence features.

a,c,e, Impact of mutagenesis represented by log2 fold change (36 h/0 h) for single-substitution (top) and deletions (bottom) mutants of each element. Horizontal grey dotted lines indicate the fold change of each wild-type element. Circle size represents adjusted p-values. P-values were calculated by Wald test with multiple testing adjustments. b,d,f, Mean log2 fold change (36 h/0 h, Log2FC) of single substitutions or 1-nt deletion represented along the RNA secondary structure of each element. ΔLog2 fold change (log2 fold change of paired nucleotides – log2 fold change of unpaired nucleotides, ΔLog2FC) is indicated with the width of the blue lines between the pairing bases. g-j, Log2 fold change distribution of sequences categorized by stem-loop features, including the presence or absence of the CNGG(N)0-2 motif and stem-loop size. Each dot represents the mean Log2 fold change of tiles across four sequencing replicates. Boxes represent the interquartile range with median (red line), and whiskers extend to 1.5 times the interquartile range.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Viral RNA stability enhancers act through TENT4-dependent mixed tailing.

a, Firefly m1Ψ-modified mRNAs of A7S element at 3′ UTR were tested for luciferase activity in Parental (HeLaT) and TENT4 double knockout cells. Cells were transfected using Lipofectamine MessengerMAX. For well-by-well transfection efficiency correction, m1Ψ-modified renilla mRNAs without functional elements were co-transfected. The level of control IVT-mRNA was used for the normalization. The luciferase signal was measured on 4 days post-transfection. Data are represented as mean ± SEM (n = 3 biological replicates). Statistical significance was determined using a two-sided Student’s t-test, with *p < 0.05. b, Hire-PAT analysis of IVT products with a 60-nucleotide (A60) tail, demonstrating that our IVT process reliably produces mRNAs of the intended poly(A) tail length. c, Poly(A) tail distribution of m1Ψ-modified mRNAs measured by Hire-PAT. Signal intensities were normalized to ensure equal areas under the curve between comparison conditions. Asterisk indicates a non-specific band. HCT116 cells were transfected using LNP, incubated with RO0321 or RG7834 (100 nM), and assayed after 24 h. A fraction of the 60-nt tail remained intact, likely due to RNA trapped within endosomes. d, Detection of changes in mixed-tailing by direct RNA nanopore sequencing with 1 µg of pooled IVT mRNAs (Control, A2, and A7). Nanopore direct RNA sequencing traces showing ionic current signals during translocation of mRNA 3′ ends. Left and right panels show identical data with different color scales for visualization. Left panels display current measurements as heatmaps (pA, color scale 50–110) for three RNA samples (Control, A2, and A7) under untreated and RG7834-treated conditions. Right panels show the same data with a grayscale background and highlighted current anomalies in blue (<80 pA) and magenta (>100 pA). Each horizontal line represents a single RNA molecule read, with 50 randomly selected reads shown per condition, ordered by decreasing poly(A) tail length. The x-axis shows time relative to the 3′ UTR end (white dashed line at 0 s), with positive values indicating the 3′ UTR region and negative values showing the poly(A) tail and downstream sequences. The expected position of a ~60-nt poly(A) tail end is marked (white dotted line, between −0.4 and −0.6 s) based on median translocation speed. Current anomalies within poly(A) tails are highlighted in blue (<80 pA) and magenta (>100 pA), indicating deviations from the expected homopolymeric adenine signal. The characteristic current drop following ~90 pA plateau marks the transition from poly(A) tail to the 3′ adapter for sequencing.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Viral RNA stability enhancers act through TENT4-dependent mixed tailing.

a, Poly(A) tail length analysis by nanopore DRS after transfecting 320 ng of electroporated IVT mRNAs (Control, A2, and A7) into HCT116 cells cultured in 12-wells. Poly(A) tail distributions for control (Ctrl), A2, and A7 element-containing mRNAs ± RG7834 treatment at 12-h post-transfection. The IVT mRNAs originally have a poly(A) tail of 60 nt. Distributions are shown as smoothed histograms to reflect total read count. White lines indicate median values; read counts are shown below. b, Detection of changes in mixed-tailing by direct RNA nanopore sequencing with 320 ng of pooled IVT mRNAs (Control, A2, and A7) same as Extended Data Fig. 3d.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Viral RNA stability enhancers act through TENT4-dependent mixed tailing.

a-d, Poly(A) tail distribution of m1Ψ-modified mRNAs measured by Hire-PAT. Signal intensities were normalized to ensure equal areas under the curve between comparison conditions. Asterisk indicates a non-specific band. HCT116 and ZCCHC14 knockout cells were transfected using LNP and assayed after 16 h (a) and 24 h (b). A fraction of the 60-nt tail remained intact, likely due to RNA trapped within endosomes. c, Parental HeLa and ZCCHC2 knockout cells were electroporated with mRNAs and assayed after 12 h. d, Parental HeLa and ZCCHC2 knockout cells were transfected using LNP and assayed after 24 h. A fraction of the 60-nt tail remained intact, likely due to RNA trapped within endosomes.

Extended Data Fig. 6 A7 functions regardless of the molecular contexts.

a, AUC values measured from Day 0 to Day 5 in HCT116 using the same method as in Fig. 5c. AUC was calculated by integrating the curve from the starting to the ending time point, after subtracting the signal from the untransfected sample. Data are represented as mean ± SEM (n = 3 biological replicates). Statistical significance was determined using a two-sided Student’s t-test, with **p < 0.01.

Extended Data Fig. 7 A7 confers circRNA-like stability to linear mRNA.

a, RNA Tapestation analysis showing circRNA IVT products at each enrichment step (GTP; enhancement of circularization for IVT products, RNase R; digestion of linear RNA, Gel purification; size selection of circularized RNA). b, ISG15 and IFIT2 mRNA levels after poly(I:C), m1Ψ-modified mRNA, and circular RNA transfection in HCT116 cells were measured by RT-qPCR. ISG15 and IFIT2 mRNA levels were normalized by GAPDH mRNA levels. Data were represented as mean ± SEM (n = 3 biological replicates). Statistical significance was determined using a two-sided Student’s t-test, with *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01. c-f, Repeated in vivo experiments illustrated in Fig. 6h–k, yielded the same results.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Jung, SJ., Seo, J.J., Lee, S. et al. RNA stability enhancers for durable base-modified mRNA therapeutics. Nat Biotechnol (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-025-02891-7

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

Version of record:

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-025-02891-7