- Review Article

- Open access

- Published:

- Suradip Das ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5716-66051,2 na1,

- Wisberty J. Gordián-Vélez1,2,3 na1,

- Jay R. Dave ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9940-515X1,2,

- Zarina S. Ali1,

- Harry C. Ledebur4 &

- …

- D. Kacy Cullen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5355-52161,2,3

Nature Communications volume 16, Article number: 9834 (2025) Cite this article

Subjects

Abstract

Engineering replacement organs is the next frontier in therapeutic technologies. Yet, the integration of innervation—critical for organ development, function, and homeostasis—remains underexplored. This review highlights the role of neural inputs in regulating critical organs including pancreas, liver, salivary gland, and spleen. We examine organ-specific neuroanatomy and emerging strategies to incorporate neuronal-axonal networks in engineered organs, drawing from innovations in scaffold design, multi-cell culture techniques, neural engineering, and biofabrication. Finally, we discuss tools for evaluating innervation across in vitro, preclinical, and clinical settings, advocating for innervation as a core design element in next-generation artificial organs.

The leap from tissue engineering to organ engineering

More than three decades after Joseph Murray performed the first human organ (kidney) transplantation, Y.C. Fung, a pioneer in the field of biomechanics, first introduced the concept of “tissue engineering” in 1985 in his proposal to the National Science Foundation (NSF)1. Tissue engineering was born out of the necessity to find a balance between the translational relevance of cellular-level findings and the experimental feasibility of fabricating a whole organ. From the days of the Vacanti mouse2, tissue engineering has made incredible progress over the last few decades, leading to multiple tissue-engineered medical products in clinical trials. Parallel advances in the field of biomaterials, 3D bioprinting and immunotherapy have encouraged biomedical engineers to leap from tissue engineering to whole organ engineering, thereby constantly closing the gap between experimental feasibility and clinical need to solve the organ shortage conundrum. Initial attempts at fabricating a whole organ followed a top-down approach wherein decellularized organs served as a scaffold to culture autologous cells3,4,5. The limited availability of cadaveric tissue/organs has been a major challenge for such top-down approaches to organ manufacturing5. On the other hand, bottom-up approaches to whole organ engineering involve fabricating the smallest structural/functional unit of the organ and using it as a building block to recreate the complex architecture, usually following additive manufacturing techniques like 3D bioprinting. Presently, it is possible to leverage stem cell biology and/or 3D printing to create miniaturized functional replicas of organs (called “organoids”) like liver and pancreas, as well as full-size transplantable versions of organs with comparatively simple/hollow architecture like skin, ear, and bladder. However, 3D printing a fully functional transplantable complex organ like a heart or kidney is still a “moonshot”. Among the multiple technological advancements necessary to fabricate a fully functional organ, researchers have already identified that achieving revascularization and reinnervation are two of the most critical prerequisites for ensuring survival and functionality of such bioengineered organs6.

Innervation has untapped potential in organ engineering

There has been significant progress in developing perfusable vascular networks in engineered organs, initially using top-down approaches of organ manufacturing and more recently across bottom-up approaches employing advanced 3D extrusion bioprinting techniques7. Further, several extensive reviews have been published that capture the current progress, challenges, as well as future perspectives of developing a vascularized bioengineered organ8,9,10. In contrast, innervation remains an untapped area in organ bioengineering, even though its implications in development, function, and regeneration are well established across multiple tissue/organ systems.

Innervation is key to organ growth, function, and repair

In more recent decades, the role of the nervous system in the involuntary regulation of internal organs has been expanded to virtually all other systems in the body, as contained in the autonomic nervous system (ANS) division of the peripheral nervous system (PNS). The ANS consists of sympathetic (“fight-or-flight”) and parasympathetic (“rest”) fibers that emanate from the central nervous system (CNS) and innervate organs through various pathways11,12. Preganglionic neurons of the sympathetic division emerge from paravertebral ganglia at the thoracic and mid-lumbar spinal cord and synapse at the sympathetic chain or the prevertebral ganglia with postganglionic fibers that ultimately innervate the effector organ. In contrast, parasympathetic preganglionic fibers originate from the brainstem or the sacral spinal cord and typically interact with the postganglionic component close to the target organ. Moreover, while acetylcholine (ACh) is the principal neurotransmitter between preganglionic and postganglionic fibers of any type, postganglionic sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves mainly employ norepinephrine (NE) and ACh, respectively, to communicate with and influence organs. The interaction between these efferent fibers (signal propagation towards effector organ/tissue, “motor”) and organs relies on afferent (sensory propagation towards CNS) inputs to the brain that provide information on environmental and physiological conditions in the organs (e.g., stretch receptors in the urinary bladder, baroreceptors for central blood pressure, thermoreceptors for skin blood flow)11,12. This is relayed to the autonomic nerves to regulate functions such as skin and muscle vasoconstriction, pancreatic secretions, urination, gut motility, and saliva production11,12,13. Variations in the density, sensitivity, and phenotypes of efferent and afferent inputs have also been related to various pathologies (e.g., gastrointestinal, pulmonary, cardiovascular diseases). Furthermore, although not extensively studied, innervation is increasingly being recognized as an essential component of organ development and regeneration13,14,15,16. For example, autonomic nerves contribute to organogenesis, wound healing, and tissue regrowth17 by preserving phenotypes and function in stem cell niches and presenting growth and transcription factors necessary for the maintenance of migrating cells in wounds16,18,19. In many instances, blood vessels and nerves follow the same paths, and their interactions are essential in pathfinding during development20,21,22. As a result, innervation is a crucial component of tissues and organs due to its role in development, functional regulation, modulation, and disease.

Innervation is dispensable in transplants, essential in bioengineered grafts

Innervation is dispensable during orthotopic transplantation, but innervation with the recipient generally occurs over time. For instance, allogeneic whole organ transplantation usually involves denervated organs, and they can function without immediate neural integration (like the liver, heart, and kidney). They are eventually innervated and integrated with the host nervous system. This is primarily because such denervated organs receive neuroendocrine molecules essential for functioning through the vascular supply and this serves as a short-term substitute for physical rewiring with host nerves. Curiously, multiorgan sympathetic denervation has been proposed to combat cardiometabolic diseases when diet and exercise-based approaches have failed23, demonstrating the general disregard of the critical role of innervation in maintaining homeostasis and in organ pathophysiology23. However, artificial organs fabricated through organ engineering lack the cellular complexity, maturity, and matrix architecture to function like an adult whole organ. Organs are composed of multiple distinct tissue types, each comprising diverse cellular populations. Within a given organ, both the individual cell types and tissue types exhibit highly specific spatial organization, which is essential for proper organ development, maturation, and function. Reproducing this intricate cellular heterogeneity remains a significant challenge in current organ engineering approaches. In the following sections, we discuss the cellular complexity and architectural features of various organs and explore their implications for the development of effective innervated tissue engineering strategies. Moreover, precise spatiotemporal neural connections direct organogenesis as well as play a crucial role in organ function and regeneration (Fig. 1)24. Hence, although denervated orthotopic transplants can survive and function without immediate reconnection with the nervous system, innervation is a critical component of the organ biomanufacturing process, especially in bottom-up approaches that may lack an appropriately instructive extracellular matrix (ECM) scaffold.

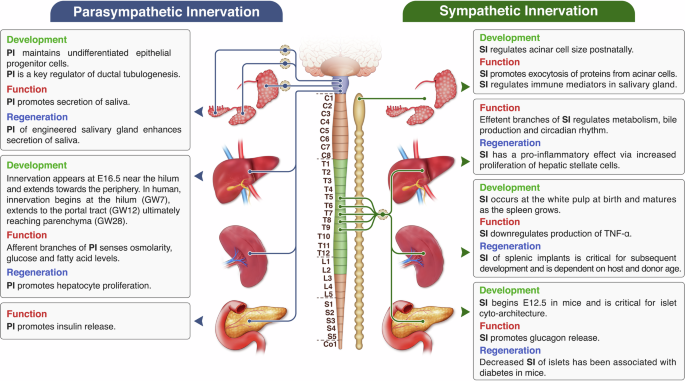

Innervation regulates all facets of organ physiology. In this review, we focus on the role of neural input in the development, function, and regulation of some key organs in the body – pancreas, salivary glands, liver, and spleen, thereby establishing the necessity of incorporating preformed neuronal networks during biofabrication of artificial organs. The schematic here provides a snapshot of the multifaceted effects of innervation in various organs of the body. Figure created with professional scientific illustration services by Inmywork.

We have previously reviewed the role of innervation in regeneration and engineering of different muscle systems, along with surgical/engineering strategies that can be employed to promote re-innervation, thereby establishing innervation as the “missing link” in tissue engineering25. In the current article, we go a step further from tissue systems to expand upon the implications of innervation in organ biology, considering critical organs like the pancreas, liver, salivary gland, and spleen as examples. We further describe current tissue engineering solutions to develop pre-innervated organs. We conclude by reviewing clinically available technologies to monitor organ reinnervation and propose strategies to engineer organs with preformed neuronal-axonal networks.

Pancreatic innervation

The distribution of nerve fibers in the pancreas varies by species. In mice, pancreatic islets display abundant parasympathetic and sympathetic innervation, with direct associations primarily to α- and β-cells, while innervation of the exocrine compartment is much less pronounced26. Conversely, human islets show limited yet predominantly sympathetic innervation27. Further, most sympathetic fibers in the human pancreas align with smooth muscle cells of islet vasculature and do not interact directly with endocrine cells27.

Innervation in pancreatic development

Pancreatic organogenesis in mice begins at embryonic day E 9.5, as buds emerge from the foregut endoderm, followed by epithelial branching and clustering of endocrine precursor cells (Fig. 2)28. Sympathetic neurons expressing vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) are detectable beginning E12.5 within the developing pancreatic bud (Fig. 2)29, when the neural crest cells around the pancreatic epithelial cells undergo neuronal differentiation30. These VMAT2+ axons become integrated with vasculature concurrent with postnatal islet maturation29.

This captures the current state-of-the-art and indicates knowledge gaps in understanding the implications of innervation in organogenesis. (Figure created in BioRender – https://BioRender.com/ocgy6s0).

Sympathetic nerves critically shape the architecture of pancreatic islets during embryogenesis14. In human development, innervation from the celiac ganglion invades the pancreatic primordium by gestational week 6 (GW6), and by GW9, multiple sources—including the celiac plexus, vagus nerve, and superior mesenteric plexus—contribute to the innervation31. Nerve ending density then decreases by GW30–3232. Adult islet structure facilitates appropriate β-cell interactions and insulin secretion33, with deviations linked to diabetes34. Experimental denervation in neonatal mice disrupts typical α-cell localization around β-cell cores, while deletion of TrkA in sympathetic neurons results in disorganized islets with diminished cell–cell adhesion14. TrkA mutant mice lacking sympathetic innervation also manifest decreased NCAM and E-cadherin expression and altered islet positioning, highlighting innervation’s role in cell clustering and migration14.

Innervation in functional regulation of the pancreas

Although the pancreas can sustain function independent of direct innervation26, autonomic signaling orchestrates insulin release during the cephalic phase, sustains glucose tolerance, synchronizes islet activity, and modulates responses to hypoglycemia and diabetes14,35,36. Exogenous agonizts to muscarinic receptors and external stimulation of vagus nerve has been shown to promote insulin release whereas hypoglycemia also leads to parasympathetic activation and modulation of glucagon secretion14,35,36,37. Conversely, sympathetic stimulation suppresses glucose-stimulated insulin secretion and enhances glucagon output through norepinephrine (NE) signaling on islet adrenergic receptors35. Two regulatory mechanisms have been proposed: direct neurotransmitter release in mice and NE-dependent vascular contraction in humans, regulating islet blood flow and hormone distribution (“spillover”)27,38. However, the “spillover” does not account for the rapid breakdown of acetylcholine by acetylcholinesterase38. Altered innervation density is implicated in pancreatic disorders. Diabetic rats show early sympathetic fiber loss39, and insulitis in non-obese diabetic mice associates with reduced islet innervation and elevated neurotrophins that indicate the body’s marked attempts to promote nerve ingrowth and islet survival40.

Salivary gland innervation

The parotid gland receives parasympathetic nerves from the otic ganglion, whose preganglionic fibers originate in the inferior salivatory nucleus of the medulla15. Preganglionic nerves from the superior salivatory nucleus in the pons join the facial and lingual nerves to ultimately innervate the submandibular and sublingual glands via the submandibular ganglion15. Sympathetic innervation involves preganglionic fibers projecting to the superior cervical ganglia, with postganglionic axons traveling to salivary glands through the external carotid plexus15.

Innervation in salivary gland development

During mouse submandibular gland development, the oral epithelium infiltrates neural crest–derived mesenchyme at E11, establishes a single duct by E12, and branches extensively by E14 (Fig. 2)41. Early parasympathetic innervation from the submandibular ganglion aligns with epithelial branching of the submandibular gland, guiding axonal trajectories42. Likewise, parotid duct branching initiates when otic ganglion–derived nerves reach the epithelium15. Parasympathetic nerves maintain progenitor epithelial populations, as removal of the submandibular ganglion reduces cytokeratin-5/−15 positive progenitor cells and developmental end bud formation43. These deficits are mimicked by inhibiting acetylcholine (ACh) signaling, and reversed with ACh analogs, confirming the role of parasympathetic innervation-derived ACh in maintaining epithelial progenitor populations43. In addition, Neurturin blockade impairs parasympathetic-mediated ductal tubulogenesis, with vasoactive intestinal peptide identified as the key promoter (Fig. 2)44. Critical windows exist for parasympathetic or sympathetic interventions: early postnatal (48 h after birth) parasympathectomy impedes myoepithelial differentiation in acinar buds, whereas later timing spares acinar maturation and gland size45. On the other hand, neonatal sympathectomy reduces acinar size and granule content, and adult interventions shrink parotid glands while altering protein output46,47 (Fig. 2).

In humans, parasympathetic neurons drive salivary branching and morphogenesis from early stages, whereas sympathetic associations are delayed until later development48,49. The submandibular ganglion forms around GW6, with innervation of parenchyma and duct by GW848,50.

Innervation in functional regulation of the salivary gland

Autonomic nerves control salivary gland output by modulating acinar contraction, saliva composition, and local blood flow51. Parasympathetic stimulation dominates serous and mucous secretion in major glands. Sympathetic signals primarily drive protein exocytosis from acinar cells, though parasympathetic input also contributes15,51.

Hepatic innervation

The extrinsic neuroanatomy of the liver is generally conserved across species. However, there is considerable species-wise variation in the distribution of intrahepatic nerves that make up the intrinsic neuroanatomy of a liver52,53. For example, rats and mice only present an extrinsic supply of sympathetic nerves limited around the portal triad, whereas in humans’ sympathetic efferent branches extend deep inside the hepatic lobules and has direct contact with hepatocytes52. This lack of direct sympathetic innervation within rat hepatic lobules is compensated by the abundance of cellular gap junctions between rat hepatocytes54.

Innervation in hepatic development

Spatiotemporal patterns of development of hepatic innervation varies widely among species and is mostly unclear. However, previously reported developmental studies indicate that innervation plays a crucial role in liver morphogenesis and stabilization of portal tract structures. In mice, innervation first appears around the primitive extra-hepatic biliary ducts at E17.5 and slowly extends towards the liver throughout the initial postnatal term. Axon outgrowth within the liver is guided by ectopic expression of NGF by murine biliary epithelial cells (Fig. 2)55. A separate study on mouse hepatic innervation observed initial traces of neuronal cell bodies near the hepatic hilus at E16.5 that spread towards the periphery by P28 (Fig. 2)56. In humans, innervation begins in the developing liver much earlier as compared to mice. Initial evidence of nerve fibers is seen as early as gestational week 7-8 near the hilum. Subsequently, by week 12, the portal tract receives the bulk of PGP9.5-expressing nerves. Intrasinusoidal innervation in humans is only observed beginning at 28 weeks (Fig. 2)57.

Innervation in functional regulation of liver

Hepatic afferent nerves express a myriad of chemoreceptors that act as sensors for osmoreception, glucose and fatty acid levels, relaying information back the CNS58. Efferent pathways within the liver regulate the hepatic vasculature, bile production, metabolism and maintain circadian rhythms via secretion of a variety of neurotransmitters (aminergic, cholinergic, peptidergic and nitrergic). Efferent pathways have also been implicated in liver repair, regeneration, as well as in pathology58.

Hepatic afferent neurons lining the portal vasculature can detect the osmolarity of fluids through specific ion channel receptors. Decreased osmolarity, triggered by water intake, is sensed by hepatic afferents and transmitted via dorsal root ganglia to efferent sympathetic fibers that increase norepinephrine production and blood pressure (pressure reflex)59. Further, the liver maintains ionic concentration (like Na+) of fluids through the hepatorenal reflex that involves decreased renal sympathetic activity in response to increased blood Na+ concentration, thereby leading to urinary excretion of Na+60. The liver plays a central role in sensing glucose and lipid levels and subsequently modulating glucose and lipid metabolism. A gradual decrease in glucose levels in the portal vein is detected by GLUT2 glucose transporters that activate vagal afferents, leading to an increase in food uptake61. On the other hand, vagal efferent activity induces secretion of Hepatic Insulin Sensitizing Substance (HISS) from the liver that promotes glucose storage in skeletal muscle, decreases glucose production and increases glycogenesis62. Stimulation of the sympathetic splanchnic nerve results in an opposite effect, increasing glucose production and decreasing glycogenesis63. Autonomic input regulates overall lipid metabolism in the liver through monitoring levels of free fatty acids (especially linoleic acid and triglycerides) by vagal afferents, leading to reduced food intake, whereas decreasing the secretion of lipids (VLDL and Apo-B) by hepatocytes following sympathetic stimulation64. Liver regeneration following vagotomy is delayed due to decreased activity of aspartate transcarbamoylase65. On the other hand, the sympathetic nervous system has been shown to inhibit the activity of hepatic oval cells (HOC), which are the resident stem cells and promote the proliferation of fibrogenic hepatic stellate cells (HSC), which are involved in the progression of disease like cirrhosis66.

Spleen innervation

Sympathetic postganglionic axons reach the spleen via the splenic nerve, with their cell bodies in prevertebral ganglia. These fibers accompany splenic artery branches targeting especially the white pulp and occasionally marginal zones67,68. These axons interface with preganglionic fibers within the greater splanchnic nerve coming from the thoracic spinal cord (T9-T11)69. Parasympathetic innervation of the spleen is reportedly minimal and still under debate70,71.

Innervation in spleen development

In rats, noradrenergic fibers emerge in the white pulp at birth, proliferating alongside splenic compartment growth. These fibers encircle developing follicles, organizing within the Periarteriolar lymphoid sheaths (PALS) structure as lymphocytes are redistributed72. The pattern of noradrenergic innervation develops steadily from day 13 onward73 (Fig. 2). In humans, the spleen is primarily innervated by the splenic nerve, composed of sympathetic noradrenergic fibers originating from the celiac ganglion, suprarenal ganglia, and thoracic sympathetic chain. The sympathetic neurons are responsible for regulating immune responses74. Spleen has few parasympathetic neurons, but the parasympathetic innervation of the spleen is poorly understood74.

Innervation in functional regulation of the spleen

Sympathetic innervation of the spleen contributes to innate immune regulation, affecting activity of natural killer cells, dendritic cells, macrophages, and other types of leukocytes75. During acute inflammation, NE released from sympathetic axons binds β-adrenergic receptors on macrophages, suppressing TNF-α production in response to endotoxin exposure76,77. Stress-induced sympathetic signals decrease cytokine output, while splenic nerve resection blocks this immune suppression78.

Neurological damage can disrupt splenic innervation, resulting in elevated NE, increased splenocyte apoptosis, impaired antibody synthesis, and greater infection susceptibility79. Such persistent immune suppression is a consequence of a hyperactive anti-inflammatory reflex circuit below the spinal cord injury site, resulting from chronic maladaptive plasticity80.

Criticial design components for innervated organ biomanufacturing

The multi-tissue composition, diverse physiochemical properties, intricate architecture, and range of functions displayed by an organ determine critical design criteria for organ biomanufacturing, like choice of fabrication technique(s), cells, and appropriate scaffolding materials. As organs are exponentially more complex in form and function as compared to tissues, conventional tissue engineering techniques do not automatically translate into engineering whole artificial organs.

Biofabrication technique

It is essential for organ manufacturing technologies to have the capacity to integrate heterogeneous cell types and multiple materials to recapitulate native organ geometries, constituents, and functions81. Organ manufacturing technologies vary in degree of automation, ranging from fully automated multi-nozzle rapid prototyping and additive molding as to more manually intensive top-down approaches like decellularization/recellularization of ECM-based matrix. Commonly used strategies include extrusion-based printing, inkjet printing, laser-assisted bioprinting, microfluidic printing, sacrificial printing, and scaffold-free approaches. Among these, extrusion-based printing is most widely applied due to its compatibility with a variety of bioinks and ability to print high-viscosity, cell-laden materials82. However, it can impose shear stress on cells and has lower resolution compared to other methods83. Inkjet printing, while capable of high resolution and speed, is best suited for low-viscosity, low-cell-density inks to avoid nozzle clogging83. Laser-assisted bioprinting enables precise, contactless cell placement with minimal damage. Sacrificial printing allows the creation of internal channels and complex vascular-like networks, enhancing nutrient and oxygen transport. Bioinks, typically composed of natural or synthetic hydrogels with embedded cells, must support key scaffold properties such as mechanical strength, porosity, and cell adhesion83. Several comprehensive reviews have emphasized the importance of tuning material properties such as mechanical strength, polarity, porosity, and cell adhesion to facilitate the successful fabrication of tissues and organs via 3D printing83,84,85,86,87. Overall, 3D printing provides a versatile platform for engineering tissue constructs with controlled architecture and biological function. The complexity of the target organ will determine the appropriate choice of fabrication technique. For example, tailoring these properties helps guide specific cellular behaviors, including promoting apicobasal polarity in epithelial tissues like salivary glands88, replicating key aspects of the liver’s in vivo microenvironment, including hepatic lobule architecture and vascular-like hollow-channel networks89. Organs with comparatively simpler geometry (e.g., skin, bladder) that possess a multi-layered architecture and/or ease of access (e.g., skin, ear) can generally be 3D bioprinted by layer-by-layer assembly of cells and scaffolds. However, the internal architecture of organs like the liver, heart and kidney is incredibly more complex geometrically as well as biologically, with heterogeneous distribution of different types of tissue like parenchyma, vascular and neural, with each tissue comprising multiple cell types. Further, each tissue and cell type must work in tandem to carry out a variety of functions. Hence, using a decellularized matrix as an instructive ECM that maintains the geometrical complexity, to seed multiple types of cells has been the prevalent manufacturing strategy for such organs. Although, with the advent of multi-nozzle 3D bioprinting techniques, it is now possible to precisely mix and print a varierty of scaffolds and cells, there is still a long way to go before 3D printing a whole fully functional organ like heart or liver becomes a reality.

Considering that the arborization of vascular/microvascular networks is somewhat similar to the multiscale network formation exhibited by neurons, it is prudent to leverage on fabrication techniques that have demonstrated the capacity to generate intra-organ vascular networks and adapt them to generate neural networks in a bioengineered organ. One approach to fabricate volumetric 3D vascular network involves “writing” microchannels via highly focused (single point in 3D space) laser-based degradation of a photodegradable hydrogel using two-photon microscopy. Although it is possible to fabricate channels as small as 5 µm diameter, such methods are inefficient to scale up for whole organ applications90. In addition, the application of high-intensity light in bioprinting can result in adverse effects, including thermal damage to tissues, phototoxic stress on cells, and the introduction of toxic byproducts from photoinitiators91. In contrast, direct extrusion 3D bioprinting offers volumetric printing capability at a larger scale but has limited print resolution92. Freeform reversible embedding of suspended hydrogels (FRESH) is another platform involving a bioink printed within a dissolvable support bath comprising gelatin microparticles, that has been used to fabricate components of the human heart with multiscale vasculature with lumens as small as 100 μm in diameter93. More recently, Grebenyuk et al., demonstrated perfusion of large-scale tissues (multi-mm3 engineered tissues) employing a 3D soft microfluidic strategy enabled by a 3D-printable 2-photon-polymerizable hydrogel formulation, which allows for precise microvessel printing at scales below the diffusion limit of living tissues94. In another study, Yao et al., generated functional 3D arrangements of cortex-like structures and segregated gray- and white-matter tracts by 3D bioprinting cortical neuron-laden gelatin hydrogel bioink in a crosshatch pattern. It was possible to recapitulate elaborate axonal arborization in the order of millimeters in the xy plane and spanning a depth of 200 µm, therby mimicking native neural circuits95. Recent advances in neural engineering have leveraged various bioprinting strategies based on extrusion and light-based techniques, as well as bioassembly strategies involving scaffold-free, hydrodynamic and acoustic techniques to construct complex, functional neural tissues96,97,98,99. Qiu et al. comprehensively reviewed the current bioprinting strategies employed in engineering CNS networks, detailing the advantages and limitations of each modality. They particularly emphasized the critical role of hydrogel properties in supporting neural cell survival and function post-printing. Both natural hydrogels (e.g., alginate, chitosan) and synthetic variants (e.g., PEG-based materials) were discussed as promising bioinks, each offering unique biochemical and mechanical cues conducive to neural cell maintenance100. In the current review, we summarize and tabulate techniques employed to fabricate not only neuronal networks but also complex, neuron-based multicellular platforms such as neuroglial, neurovascular and neuromuscular systems, emphasizing their potential in advancing organ-level innervation for functional tissue and organ regeneration (Table 1). In a novel application of hydrodynamic assembly, enzymatically dissociated dorsal root ganglion (DRG) were spatially organized into micro-scale tissue units. This gentle assembly method preserved the native tissue microstructure, including the close association between neurons and satellite glial cells. This method was used to fabricate multicellular constructs of cytokine-primed annulus fibrosis (AF) explant and primary bovine dorsal root ganglion (DRG) to investigate nerve ingrowth. The multicellular constructs were characterized using phase-contrast imaging and immunofluorescence staining, allowing visualization of cell types such as CGRP-positive nociceptors and their axonal projections96. To engineer human cerebral cortex-like microtissues using acoustic assembly involved the generation of six-layered concentric neural architectures by acoustically patterning hiPSC-derived neural stem cells (hNSCs) or mature neurons within a collagen I–Matrigel hydrogel. This platform mimicked the structural and functional organization of the human cerebral cortex and was designed as an in vitro model for studying neurological disorders, particularly Alzheimer’s disease, and for preclinical drug screening97. A functional neural network platform was developed using multimaterial-multicellular bioprinting by using human pluripotent stem cell-derived neuronal progenitors differentiated into cortical glutamatergic neurons, GABAergic interneurons, and striatal medium spiny neurons, combined with astrocyte progenitors in a customized bioink made of fibrin and hyaluronic acid. This formulation supported cell survival, neurite extension, synaptogenesis, and the formation of complex neural networks both within and across printed layers. The printing method’s spatial control enabled efficient nutrient diffusion and structural stability, making the platform suitable for studying human neural circuits and modeling neurological diseases101. Kim et al. investigated a multicellular strategy involving human muscle progenitor cells (hMPCs) and hNSCs. Integration of neural cells into the bioprinted skeletal muscle constructs showed improved myofiber formation, long-term survival, and neuromuscular junction (NMJ) formation in vitro. The hNSCs differentiated into glial cells and neurons, with neurites contacting acetylcholine receptor (AChR) clusters on myotubes. These results highlight the importance of incorporating neural elements into muscle tissue engineering strategies to accelerate reinnervation and improve functional outcomes102. Together, these innovative strategies highlight rapid progress in 3D printing of neuronal networks, offering powerful and increasingly physiologically relevant techniques that, when coupled with organ bioprinting platforms, can lead to the development of innervated artificial organs.

Cellular biomass

The choice of cellular biomass, methods to obtain very high-density cultures with sufficient purity, as well as optimizing multiple cell culture parameters to ensure all the cell types survive, mature, and function, is perhaps the most challenging aspect of organ biomanufacturing. Incorporating innervation as a design component further accentuates this challenge, as there is a lack of standardized protocols that can develop autonomic neurons at a scale, maturity, and phenotype specificity sufficient to meet the requirements of a whole bioengineered organ. Nevertheless, autonomic neurons isolated from rodent primary tissue and differentiated from human iPSC cells remain our best bet for preclinical and clinical studies (Table 2).

Scaffolds and biomolecules

In tissue engineering, a scaffold can be described as a biomaterial structure designed to act as a temporary or permanent three-dimensional framework to provide different functions such as support cell growth, organization, and/or differentiation, drug delivery and/or cellular modulation. Scaffolds, along with biochemical cues, are not just a delivery vehicle for cells but function as dynamically modulated microenvironments in vitro and in vivo. Hence, the choice of scaffolding material is a critical design question in organ manufacturing. Several synthetic and natural polymers have been used to engineer artificial tissues/organs, and there are extensive reviews that detail the pros and cons of each material, their physical and biological properties and suitability to various organ manufacturing techniques. Engineering neural networks is facilitated by certain scaffold properties like anisotropic structure, porosity, biodegradability, and electrical conductivity. Several natural polymers like collagen I, gelatin, hyaluronic acid, as well as synthetic polymers like polycaprolactone (PCL), poly-L-lactic acid (PLLA), poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) in combination with conductive polymers like polypyrrole, polyaniline, carbon nanotubes have been shown to facilitate neurite outgrowth and nerve regeneration103,104. Incorporation of neurotrophic factors like Nerve Growth Factor (NGF), Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF), and Glial Cell Line-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (GDNF) in the scaffold significantly improves nerve regeneration104. An ideal cocktail of scaffolding mixture for fabricating a well-defined neural network system within a bioengineered organ would comprise of one or multiple polymers along with key growth factors that provide the appropriate milieu for maturation, arborization and integration of neural cells105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115 (Table 1).

In the following sections, we attempt to provide potential strategies that may be useful in addressing the key design criteria for innervated organ biomanufacturing. We have chosen pancreas, liver, spleen and salivary gland, as examples to analyze the architecture and cellular distribution of target organs and determine a potential combination of scaffold, cells and biomolecules that may be used while manufacturing innervated bioengineered versions of these organs.

Innervated bioengineered pancreas

Research in animal models ranging from insulin-resistant to diabetic strains reveals that pancreatic function is adversely affected by sympathetic denervation35,116,117. Nevertheless, regeneration strategies have largely targeted revascularization, often treating sympathetic nerve regrowth as an incidental effect118. Pancreatic constructs with pre-formed vasculature experience delayed functional onset after transplantation119,120 due to sporadic sympathetic innervation119. Phelps et al., cultured rat islet cells on a monolayer of hippocampal neurons and reported superior islet adhesion and spreading as compared to islet cultures on a non-neuronal cell monolayer or ECM based coating121,122. Further, neuron-islet cell coculture formed an interconnected network with readily apparent neuronal-islet cell contacts121. These reports establish innervation and neurochemical signals as vital for pancreatic development and function, thereby making appropriate neuronal input central to designing bioengineered pancreatic constructs.

Based on the physiology of the pancreas, we anticipate that to engineer a functional pancreatic tissue, it is necessary to coculture pancreatic acinar cells and beta islet cells on an appropriate scaffold (Fig. 3). Beta islet cells can be isolated and cultured from rat or human tissue as described in previous literature121,123. Beta cells have been reported to have a strong preference for specific ECM components that should be considered for designing the scaffold124. Primary pancreatic acinar cells from mice or humans can also be isolated following established protocols125,126. Wang et al. developed a bioink composed of pancreatic extracellular matrix (pECM) and hyaluronic acid methacrylate (HAMA) to 3D print functional islet organoids. These constructs preserved islet functionality and enhanced bioactivity. Upon implantation in diabetic mice, they elevated insulin levels and maintained normoglycemia for 90 days, with the pECM/HAMA hydrogel promoting greater angiogenesis than HAMA alone127. Similarly, a 3D culture system was developed using human induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived nociceptors to model peripheral nerve (PN) structures and tissue innervation. By co-culturing nociceptor neurospheres with primary rat Schwann cells on aligned polycaprolactone (PCL) microfibrous scaffolds, the system achieved enhanced neurite outgrowth, directional alignment, and myelination compared to conventional 2D substrates such as laminin-, Matrigel-, or Schwann cell-coated glass coverslips. The platform also demonstrated its capacity for tissue innervation by integrating engineered nerves with pancreatic pseudoislets and endometrial organoids embedded in a fibrin hydrogel. Immunofluorescence analysis confirmed the extension of nociceptor axons into these target tissues, underscoring the platform’s potential for studying neural interactions with peripheral organs in vitro128. In addition, islet cells have been reported to mature better in the presence of neurons121, we anticipate that simultaneous coculture of the islets and autonomic neurons might provide the appropriate milieu for their growth. Thus, pancreatic acinar, islet cells, parasympathetic neurons and sympathetic neurons can be incorporated into the separate bioinks to 3D print a pancreatic organoid mimicking the natural anatomy using a multi-material multi-nozzle approach (Fig. 3). The ideal parasympathetic cell source for biofabrication of an innervated pancreas appears to be the submandibular ganglia129. The superior cervical ganglia would be a good source of sympathetic population130 for the pancreas. Once the organoid containing the coculture is adequately innervated with autonomic axons, the entire setup can be transferred into a bioreactor for maturation, leading to the formation of an innervated pancreatic tissue.

A potential experimental strategy for developing innervated pancreatic tissue is elucidated in the following steps – Step 1 Isolation and primary culture of pancreatic acinar and beta islet cells from murine or human sources; Step 2 Incorporation of acinar and islet cells in an appropriate bioink; Step 3 Isolation and primary culture of sympathetic and parasympathetic populations from celiac ganglia and submandibular ganglia (SMdG) respectively; Step 4 3D printing of innervated pancreatic organoid containing pancreatic cells, sympathetic and parasympathetic neurons using multi-material multi-nozzle approach; Step 5 The whole setup may be transferred for culture and maturation in a bioreactor. Figure originally created with professional scientific illustration services by Inmywork and subsequently modified by the authors using BioRender – https://BioRender.com/dlkhs9r).

Innervated bioengineered salivary gland

Restoration of salivary gland function following damage from radiation, aging, or Sjogren’s syndrome is critical, as loss of secretion leads to oral pathologies such as bacterial infection and impaired taste131,132,133. Adult mice transplanted with bioengineered submandibular glands, developed from epithelial and mesenchymal germ layers, show innervation by host axons within 30 days134. Such re-innervation led to saliva secretion from the artificial gland through gustatory stimulation by citrate134. This underscores the importance of engineering strategies conducive to re-innervation for functional restoration of artificial salivary glands.

Engineering a functional salivary gland would first require selecting the appropriate source of salivary acinar cells, depending on the target gland (parotid/submandibular/sublingual)135,136. One approach involved a magnetic 3D bioprinting (M3DB) strategy to create salivary gland (SG) spheroids. In this experiment, human dental pulp stem cells (hDPSCs) were first tagged with magnetic nanoparticles, then formed into spheroids using gravity, centrifugation, and a magnetic pin drive. These spheroids were subsequently treated with FGF10 to induce SG epithelial differentiation and transplanted into ex vivo models88. In a separate study, salivary epithelial cells and cortical neurons were simultaneously plated to develop a coculture model137. Wu et al, demonstrated coculture of human stem cell derived parasympathetic neurons with rat salivary gland epithelial cells138. Like the pancreas, the submandibular ganglia and superior cervical ganglia can be used to isolate parasympathetic and sympathetic neurons, respectively129,130. Hence, we anticipate mimicking the salivary gland anatomy using 3D printed organoids comprising an appropriate bioink with acinar cells. These organoids integrated with neuronspheres made of a mixed population of sympathetic and parasympathetic neurons would be the appropriate model to fabricate a functional innervated salivary gland (Fig. 4).

A potential experimental strategy for developing innervated salivary gland tissue is elucidated in the following steps – Step 1 Isolation and primary culture of salivary acinar cells from any of the 3 salivary glands depending upon the target organ; Step 2 Incorporating of acinar cells on an appropriate bioink and 3D printing salivary gland mimicking their native geometry; Step 3 Isolation and primary culture of sympathetic and parasympathetic populations from superior cervical ganglia and submandibular ganglia respectively; Step 4 Plating and culture of sympathetic and parasympathetic neuro-spheres on the 3D printed salivary gland containing acinar cell population; Step 5 Upon adequate axonal infiltration into the salivary acinar cells from adjacent autonomic ganglia the whole setup may be transferred for culture and maturation in a bioreactor. Figure originally created with professional scientific illustration services by Inmywork and subsequently modified by the authors using BioRender – https://BioRender.com/dlkhs9r).

Innervated bioengineered liver

The enormous burden of chronic liver diseases and rapidly increasing prevalence of death from liver-related diseases, especially cirrhosis, has considerably widened the gap between demand and supply of liver transplants. The field of liver tissue engineering aims to ameliorate this situation by utilizing the basic tenets of tissue engineering to develop engineered hepatic tissue in the form of a fully functional organ or extracorporeal device that can repair or replace the functioning of the liver in total or in part. Over the years, a combination of appropriate cells and biomaterials have been used in a bottom-up as well as top-down approach to mimic the structure and function of hepatic tissue139. In terms of materials, myriads of natural materials and synthetic polymers have been explored as scaffolds for engineering hepatic tissue140. Although hepatocytes have been the primary cell source, other non-parenchyma cells like Kupffer cells, hepatic stellate cells and endothelial cells have also been incorporated in combination with hepatocytes to generate a biomass that is more representative of the multicellular hepatic niche141,142,143,144. Back in 1989, Westergaard et al. set up a neuron-hepatocyte system through the coculture of rodent hepatocytes and glutamatergic neurons145. Since then, neuronal cells are yet to be utilized as an important non-parenchyma component in liver tissue engineering. In an interesting development, Harrison et al. recently observed that liver organoids generated from human pluripotent stem cells developed de novo vascularization and innervation within the organoid by Day 20146. These vascularized and innervated hepatic organoids recapitulated the multicellular niche of the liver and exhibited key liver functions and long-term survival upon transplantation, thereby emphasizing the importance of further research towards engineering hepatic tissue with a preformed neuronal network.

Developing an engineering liver tissue with a preformed neural network entails careful selection of hepatocyte and relevant non-parechyma cell source, culture, and maintenance along with appropriate neuronal choice on a scaffold that mimics the architecture of liver lobule (Fig. 5). Some of the most critical design considerations while engineering an artificial liver should involve – (a) hexagonal architecture of hepatic lobules comprising radially aligned hepatocytes, (b) intricate network of bile canaliculi and liver sinusoids that transport bile and blood in opposite directions, c) intrasinusoidal distribution of sympathetic neurites in human and d) hepatocyte polarization wherein the apical membrane helps in flow of bile whereas basolateral membrane is used to secrete serum proteins into the blood flowing through sinusoids. With advancements in 3D printing technology, there have been attempts at developing hepatic lobule-like honeycomb structures comprising hepatocytes and endothelial cells, mainly for the purpose of drug testing. To scale up such fabrication, Kang et al. developed a 3D extrusion bioprinting technique to generate highly vascularized complex liver tissue recapitulating native architecture from micro- to macro-scale147. We believe that such a technique may also be used to develop innervated hepatic tissue by incorporating sympathetic and parasympathetic neurons in the bioink along with hepatocytes and liver sinusoidal endothelial cells. Primary hepatocytes of rodent148 or human origin149, as well as human iPSC-derived hepatocytes, can be either commercially procured or generated in-house following well-established protocols150. As endothelial cells are a major non-parenchyma component in the liver, we believe it is necessary to include liver sinusoidal endothelial derived from primary tissue151 or iPSC sources152 in the overall cell biomass in hepatic tissue engineering. Considering in rodents, sympathetic innervation is absent inside the liver lobule and as such does not contribute to liver regeneration, parasympathetic cholinergic neurons isolated from submandibular ganglia129 or tracheal tissue153 can be the sole neuronal source for engineering innervated liver tissue for rodent based studies. However, a more clinically relevant design would involve both human iPSC-derived parasympathetic and sympathetic neurons (Fig. 5)154 along with hepatocytes and sinusoidal endothelial cells as cellular biomass cultured on a scalable scaffold that mimics the micro and macro details of native hepatic tissue.

A potential experimental strategy for developing innervated hepatic tissue is elucidated in the following steps – Step 1 Isolation and primary culture of rodent derived hepatocytes or human iPSC derived hepatocytes; Step 2 Human iPSC derived or primary tissue derived liver sinusoidal endothelial cells; Step 3-4 Isolation and primary culture of parasympathetic (3) and sympathetic populations (4) from submandibular ganglia (SMdG) and celiac ganglia respectively; Step 5 Preparing a cellular bioink combining all the cell types in appropriate ratios and arranged in a biofidelic hexagonal architecture; Step 6 3D printing a complete hepatic lobule following similar procedure as outlined by Kang et al., 2020 with pre-formed neural and vascular networks. (Figure created in BioRender – https://BioRender.com/q72n875).

Innervated bioengineered spleen

Tissue engineering has been applied to improve substrates for longer-term spleen slice culture (e.g., fabricating TiO2 nanotube scaffolds to replace standard polytetrafluoroethylene membranes) that can be utilized for neurobiological studies or drug testing in vitro155. In the realm of regenerative medicine, tissue-engineered spleens have been developed by seeding multicellular splenic units isolated from juvenile rats into tubular scaffolds of polyglycolic acid coated with poly-L-lactic acid and then implanting them in the omentum156. These constructs significantly supported survival in splenectomized rat models of pneumococcal sepsis, suggesting they may serve as substitutes to transplanted slices for spleen regeneration after resection156. To our knowledge, innervation has not been explored in tissue-engineered strategies designed to modulate inflammatory responses or restore immune function through the spleen or cells from other immune organs, although this would be a promising future direction for proper biofabrication in vitro as well as regulation in vivo.

Innervation in the spleen is arguably primarily of sympathetic origin, as we have described earlier. The spleen consists of a variety of white blood cells, dendritic cells and macrophages collectively referred to as splenocytes. Hence, tissue engineering strategies should involve isolation and primary culture of splenocytes157,158 as per established procedures to accurately recapitulate splenic physiology (Fig. 6). In a separate study on splenocyte-neuron coculture, splenocytes were added to 9-day old neuronal cultures159. Hence, we believe that sympathetic neurons harvested from the celiac ganglia160 should be cultured over scaffolds for approximately a week before the addition of splenocytes (Fig. 6). Upon adequate innervation of the splenocytes, the construct may be allowed to mature and gain biomass by culturing it in a bioreactor. This can lead to an innervated and functional splenic tissue that can be used as an in vitro test bed or an implant to repair/replace a damaged spleen.

A potential experimental strategy for developing innervated splenic tissue is elucidated in the following steps – Step 1 Isolation and primary culture of sympathetic neurons from the celiac ganglia; Step 2 Plating and culture of sympathetic neurons on a scaffold and allowing axonal outgrowth into an adjacent scaffold Step 3 Isolation and primary culture of splenocytes; Step 4 Culture of splenocytes on the scaffold which already consists of sympathetic neurons; Step 5 Following innervation of the splenocytes with sympathetic neurons, the construct may be allowed to mature in a bioreactor. Figure created with professional scientific illustration services by Inmywork.

Tools and techniques to assess innervation in engineered organs

A significant challenge in creating innervated artificial organs lies in testing the neuronal phenotype and how axons interact with target organ-specific cells. Furthermore, post-implantation assessments of re-innervation in animal models and clinical settings face complications due to expensive and complex imaging tools. However, recent advancements in high-throughput assays have enabled analysis of neuronal cells’ morphology, genetics, and function. In the following sections, we outline several key tools and techniques essential to assess re-innervation and neural integration of implanted bioengineered organs.

In vitro techniques

Determining innervation is crucial to understand neural integration and functionality of the engineered tissues. The most essential technique to evaluate this is the immunocytochemical analysis, which utilizes neural-specific markers such as Tyrosine Hydroxylase (TH), synapsin, synaptophysin, PSD-95 and beta-tubulin III to visualize the structural development of neurons and synaptic connections17,27,95,121,130. To determine the functionality of the nerve connections, it is crucial to determine the levels of neurotrophic factors and neurotransmitters (such as Tyrosine Hydroxylase (TH) and Choline Acetyltransferase (ChAT)) using ELISA, this provides insights into the biochemical signaling during neural maintenance and synapse formation161,162. Further insights can be obtained by delving into the molecular levels using single-cell transcriptomics and RNA sequencing, which will reveal gene expression profiles associated with neuronal differentiation, axonal growth, and synaptic activity, offering a comprehensive understanding of neural integration processes163,164,165,166,167. Similarly, proteomics analysis identifies and quantifies proteins involved in neural and synaptic development, offering a deeper understanding of the molecular drivers of innervation163,166. A cheaper alternative to transcriptomics is validation of gene expression through qPCR, which supports the identification of critical neural markers, confirming the progress of neuronal integration41,43,44.

In vitro model systems can be developed using microfluidic systems to replicate physiological conditions that facilitate precise neuron-tissue interactions, mimicking in vivo-like conditions94,139. In addition, techniques such as live-cell fluorescent imaging provide dynamic, real-time visualization of processes such as axon growth, synapse formation, and intracellular calcium signaling, indicating neural functionality within the organ construct154. Together, these in vitro techniques form an integrated framework for evaluating structural and functional innervation in organ engineering.

In vivo techniques

Immunohistochemistry can also be applied post-mortem to study innervation in implanted organs. Non-invasive tools like pilocarpine-induced saliva production in bioengineered salivary glands or peripheral-focused ultrasound in bioengineered livers help monitor re-innervation134,168. Neuronal tract tracing techniques (using HRP, cholera toxin B, viral tracers like AAV and HSV) can visualize organ re-innervation in animal models169,170. Combining techniques like immunohistochemistry, neural tracers, and tissue clearing (e.g., immunolabeling-enabled imaging of solvent-cleared organs or iDISCO + ) allows researchers to study the innervation patterns of bioengineered organs171.

Clinical techniques

Clinical assessments of re-innervation rely on radioactive tracers and imaging modalities like single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), magnetic resonance (MRI), computed tomography (CT) and positron emission tomography imaging (PET)172. Techniques using tracers such as 11C-hydroxyephedrine (11C-HED), 11C-epinephrine and Iodine-123-meta-iodobenzylguanidine (Iodine-123-mIBG) have been applied to study sympathetic innervation in heart transplants and could be adapted for other organs. Cholinergic activity, essential for parasympathetic re-innervation, can be studied using [18F]Fluoroethoxybenzovesamicol (FEOBV) in combination with PET imaging173. These tools hold promise for assessing re-innervation following the implantation of bioengineered organs in preclinical animal studies as well as in clinical scenarios.

Summary

Innervation plays a critical role in the development, maturation, and function of organs; however, it remains an underutilized component in current tissue engineering and organ biofabrication strategies. To achieve physiologically relevant and fully functional bioengineered organs, innervation should be intentionally incorporated at multiple stages of the fabrication process. Innervation provides essential biochemical and biophysical cues that regulate cell differentiation, spatial organization, and long-term tissue functionality. Emerging evidence highlights the necessity of integrating stem cell-derived neurons, organ-specific parenchymal cells, and spatially defined scaffolds through advanced bioprinting methods to recapitulate native neuroanatomical architecture. Despite these advancements, several key challenges remain. Fabrication techniques capable of constructing neural networks at the organ-scale with high fidelity are still limited. Replicating native innervation patterns and understanding long-term integration and functionality of engineered neural networks requires further research. In addition, existing imaging modalities lack the sensitivity and specificity needed for routine clinical monitoring of neural integration. Future efforts should focus on developing multiscale bioprinting methods, region-specific innervation strategies, and clinically translatable imaging platforms. Addressing these limitations through interdisciplinary research will be essential to fully realize the potential of innervated artificial organs for therapeutic applications.

Future directions

Innervation is a critical prerequisite for organ biofabrication

Innervation has been shown to not just accompany organogenesis in utero, but to provide essential cues that drive and maintain the differentiation and specialization of critical cell types during the development of complex tissues and organs. These innervation-induced developmental mechanisms are often vital to direct the proper form and function of tissues/organs. Precisely timed and positioned integration of axons with subsequent synapse formation are the primary mediator of these crucial developmental cues. Therefore, innervation must be considered throughout the entire process of fabricating engineered organs.

Engineered innervated artificial organs requires careful selection of cells, scaffolds, and fabrication technique(s)

Choosing the appropriate source for neuronal and tissue parenchyma cells is a key decision to make during experimental design. Balancing experimental feasibility and clinical relevance, mechanistic (or discovery-based) studies focus on advancing our undersdtanding of innervation across various aspects of organ biology as well as in vivo studies can initially employ primary tissue derived cells following established protocols listed in previous sections. However, efforts to generate artificial organs for preclinical/clinical implantation purposes must consider human stem cell-derived autonomic neurons with a combination of parenchyma cells derived either from primary tissue (biopsy sample) or patient derived stem cells. Choice of scaffold biomaterials should be based on the mechanical, biochemical, and electrical properties of various tissue types within the developing and/or mature organ. In many cases, there is considerable heterogeneity of tissue properties within an organ, and it is essential to choose a combination of scaffolds that accurate recapitulates such diversity. Fabrication techniques should be chosen based on the complexity and heterogeneity of native tissue architecture within an organ. Techniques that have been shown to generate microvascular networks in artificial organs provide a promising starting point to adapt for printing multiscale neural networks. With further advancements in 3D bioprinting technology, it will soon be possible to recapitulate the innervation pattern within an organ at a high resolution and scale.

Monitoring neural integration is crucial during preclinical and clinical phases of organ biomanufacturing

Monitoring neural-tissue interactions as well as functional integration is a critical quality control parameter during all phases of organ biomanufacturing. Existing neurochemical assays, along with soft tissue imaging modalities like MRI, PET, CT need to be leveraged to assess the degree of innervation in bioengineered organs. Although there is a plethora of choices for preclinical studies, there is a need to develop more facile, cost-effective clinically relevant imaging platforms that display high sensitivity to neural tissue and high spatial specificity to innervating axons within the implanted organ.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

No new datasets were generated or analyzed for this manuscript.

References

-

Fung, Y. C. A Proposal to the National Science Foundation for An Engineering Research Center at UCSD, CENTER FOR THE ENGINEERING OF LIVING TISSUES”, UCSD #865023. (2001).

-

Cao, Y., Vacanti, J. P., Paige, K. T., Upton, J. & Vacanti, C. A. Transplantation of chondrocytes utilizing a polymer-cell construct to produce tissue-engineered cartilage in the shape of a human ear. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 100, 297–302 (1997).

-

Oberpenning, F., Meng, J., Yoo, J. J. & Atala, A. De novo reconstitution of a functional mammalian urinary bladder by tissue engineering. Nat. Biotechnol. 17, 149–155 (1999).

-

Atala, A., Bauer, S. B., Soker, S., Yoo, J. J. & Retik, A. B. Tissue-engineered autologous bladders for patients needing cystoplasty. Lancet 367, 1241–1246 (2006).

-

Ott, H. C. et al. Perfusion-decellularized matrix: using nature’s platform to engineer a bioartificial heart. Nat. Med. 14, 213–221 (2008).

-

Sohn, S., Buskirk, M. V., Buckenmeyer, M. J., Londono, R. & Faulk, D. Whole organ engineering: Approaches, challenges, and future directions. Appl. Sci. 10, 4277 (2020).

-

Pimentel, C. R. et al. Three-dimensional fabrication of thick and densely populated soft constructs with complex and actively perfused channel network. Acta Biomater. 65, 174–184 (2018).

-

Li, S., Liu, S. & Wang, X. Advances of 3D printing in vascularized organ construction. Int. J. Bioprinting 8, 588 (2022).

-

Pellegata, A. F., Tedeschi, A. M. & Coppi, P. D. Whole organ tissue vascularization: Engineering the tree to develop the fruits. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 6, 56 (2018).

-

Zheng, K. et al. Recent progress of 3D printed vascularized tissues and organs. Smart Mater. Med. 5, 183–195 (2024).

-

Gibbins, I. Functional organization of autonomic neural pathways. Organogenesis 9, 169–175 (2013).

-

Hildreth, V., Anderson, R. H. & Henderson, D. J. Autonomic innervation of the developing heart: Origins and function. Clin. Anat. 22, 36–46 (2009).

-

Keast, J. R. Innervation of developing and adult organs. Organogenesis 9, 168–168 (2013).

-

Borden, P., Houtz, J., Leach, S. D. & Kuruvilla, R. Sympathetic innervation during development is necessary for pancreatic islet architecture and functional maturation. Cell Rep. 4, 287–301 (2013).

-

Ferreira, J. N. & Hoffman, M. P. Interactions between developing nerves and salivary glands. Organogenesis 9, 199–205 (2013).

-

Kumar, A. & Brockes, J. P. Nerve dependence in tissue, organ, and appendage regeneration. Trends Neurosci. 35, 691–699 (2012).

-

Knox, S. M. et al. Parasympathetic stimulation improves epithelial organ regeneration. Nat. Commun. 4, 1494 (2013).

-

Brownell, I., Guevara, E., Bai, C. B., Loomis, C. A. & Joyner, A. L. Nerve-derived sonic hedgehog defines a niche for hair follicle stem cells capable of becoming epidermal stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 8, 552–565 (2011).

-

Yamazaki, S. et al. Nonmyelinating schwann cells maintain hematopoietic stem cell hibernation in the bone marrow niche. Cell 147, 1146–1158 (2011).

-

Carmeliet, P. & Tessier-Lavigne, M. Common mechanisms of nerve and blood vessel wiring. Nature 436, 193–200 (2005).

-

Weinstein, B. M. Vessels and nerves: Marching to the same tune. Cell 120, 299–302 (2005).

-

Larrivée, B., Freitas, C., Suchting, S., Brunet, I. & Eichmann, A. Guidance of vascular development: Lessons from the nervous system. Circ. Res. 104, 428–441 (2009).

-

Kiuchi, M. G., Carnagarin, R., Matthews, V. B. & Schlaich, M. P. Multi-organ denervation: a novel approach to combat cardiometabolic disease. Hypertens. Res. 46, 1747–1758 (2023).

-

Honeycutt, S. E., N’Guetta, P.-E. Y. & O’Brien, L. L. Innervation in organogenesis. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 148, 195–235 (2022).

-

Das, S. et al. Innervation: the missing link for biofabricated tissues and organs. Npj Regen. Med. 5, 11 (2020).

-

Rodriguez-Diaz, R. & Caicedo, A. Neural control of the endocrine pancreas. Best. Pr. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 28, 745–756 (2014).

-

Rodriguez-Diaz, R. et al. Innervation patterns of autonomic axons in the human endocrine pancreas. Cell Metab. 14, 45–54 (2011).

-

Murtaugh, L. C. & Melton, D. A. Genes, signals, and lineages in pancreas development. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 19, 71–89 (2003).

-

Burris, R. E. & Hebrok, M. Pancreatic innervation in mouse development and β-cell regeneration. Neuroscience 150, 592–602 (2007).

-

Agerskov, R. H. & Nyeng, P. Innervation of the pancreas in development and disease. Development 151, https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.202254 (2024).

-

Krivova, Y. S., Proshchina, A. E., Otlyga, D. A., Leonova, O. G. & Saveliev, S. V. Prenatal development of sympathetic innervation of the human pancreas. Ann. Anat. – Anat. Anz. 240, 151880 (2022).

-

Proshchina, A. E., Krivova, Y. S., Leonova, O. G., Barabanov, V. M. & Saveliev, S. V. Development of Human Pancreatic Innervation. (2018).

-

Yamagata, K. et al. Overexpression of dominant-negative mutant hepatocyte nuclear factor-1α in pancreatic β-cells causes abnormal islet architecture with decreased expression of E-Cadherin, reduced β-cell proliferation, and diabetes. Diabetes 51, 114–123 (2002).

-

Kilimnik, G. et al. Altered islet composition and disproportionate loss of large islets in patients with type 2 diabetes. PLoS ONE 6, e27445 (2011).

-

Ahrén, B. Autonomic regulation of islet hormone secretion – Implications for health and disease. Diabetologia 43, 393–410 (2000).

-

Thorens, B. Neural regulation of pancreatic islet cell mass and function. Diabetes, Obes. Metab. 16, 87–95 (2014).

-

Taborsky, G. J. & Mundinger, T. O. Minireview: The role of the autonomic nervous system in mediating the glucagon response to hypoglycemia. Endocrinology 153, 1055–1062 (2012).

-

Taborsky, G. J. Islets have a lot of nerve! or do they?. Cell Metab. 14, 5–6 (2011).

-

Mei, Q., Mundinger, T. O., Lernmark, A. & Taborsky, G. J. Early, selective, and marked loss of sympathetic nerves From the islets of biobreeder diabetic rats. Diabetes 51, 2997–3002 (2002).

-

Persson-Sjögren, S., Holmberg, D. & Forsgren, S. Remodeling of the innervation of pancreatic islets accompanies insulitis preceding onset of diabetes in the NOD mouse. J. Neuroimmunol. 158, 128–137 (2005).

-

Patel, V. N., Rebustini, I. T. & Hoffman, M. P. Salivary gland branching morphogenesis. Differentiation 74, 349–364 (2006).

-

Coughlin, M. D. Early development of parasympathetic nerves in the mouse submandibular gland. Dev. Biol. 43, 123–139 (1975).

-

Knox, S. M. et al. Parasympathetic innervation maintains epithelial progenitor cells during salivary organogenesis. Science 329, 1645–1647 (2010).

-

Nedvetsky, P. I. et al. Parasympathetic innervation regulates tubulogenesis in the developing salivary gland. Dev. Cell 30, 449–462 (2014).

-

Murakami, M., Nagato, T. & Tanioka, H. Effect of parasympathectomy on the histochemical maturation of myoepithelial cells of the rat sublingual salivary gland. Arch. Oral. Biol. 36, 511–517 (1991).

-

Henriksson, R., Carlsöö, B., Danielsson, Å., Sundström, S. & Jönsson, G. Developmental influences of the sympathetic nervous system on rat parotid gland. J. Neurol. Sci. 71, 183–191 (1985).

-

Proctor, G. B. & Asking, B. A comparison between changes in rat parotid protein composition 1 and 12 weeks following surgical sympathectomy. Q. J. Exp. Physiol. 74, 835–840 (1989).

-

Quirós-Terrón, L. et al. Initial stages of development of the submandibular gland (human embryos at 5.5–8 weeks of development). J. Anat. 234, 700–708 (2019).

-

Paula, F. et al. Overview of human salivary glands: Highlights of morphology and developing processes. Anat. Rec. 300, 1180–1188 (2017).

-

Holmberg, K. V. & Hoffman, M. P. Anatomy, biogenesis and regeneration of salivary glands. Monogr. Oral. Sci. 24, 1–13 (2014).

-

Proctor, G. B. & Carpenter, G. H. Regulation of salivary gland function by autonomic nerves. Auton. Neurosci. 133, 3–18 (2007).

-

Fukuda, Y., Imoto, M., Koyama, Y., Miyazawa, Y. & Hayakawa, T. Demonstration of noradrenaline-immunoreactive nerve fibres in the liver. J. Int. Méd. Res. 24, 466–472 (1996).

-

Nobin, A. et al. Organization of the sympathetic innervation in liver tissue from monkey and man. Cell Tissue Res. 195, 371–380 (1978).

-

Seseke, F. G., Gardemann, A. & Jungermann, K. Signal propagation via gap junctions, a key step in the regulation of liver metabolism by the sympathetic hepatic nerves. FEBS Lett. 301, 265–270 (1992).

-

Tanimizu, N., Ichinohe, N. & Mitaka, T. Intrahepatic bile ducts guide establishment of the intrahepatic nerve network in developing and regenerating mouse liver. Development 145, dev159095 (2018).

-

Koike, N. et al. Development of the nervous system in mouse liver. World J. Hepatol. 14, 386–399 (2022).

-

Shimazu, T. Liver Innervation and the Neural Control of Hepatic Function. (John Libbey, 1996).

-

Jensen, K. J., Alpini, G. & Glaser, S. Hepatic nervous system and neurobiology of the liver. Compr. Physiol. 3, 655–665 (2013).

-

May, M. et al. Liver afferents contribute to water drinking-induced sympathetic activation in human subjects: A clinical trial. PLoS ONE 6, e25898 (2011).

-

Morita, H. & Abe, C. Negative feedforward control of body fluid homeostasis by hepatorenal reflex. Hypertens. Res. 34, 895–905 (2011).

-

Burcelin, R., Dolci, W. & Thorens, B. Glucose sensing by the hepatoportal sensor is GLUT2-dependent: in vivo analysis in GLUT2-null mice. Diabetes 49, 1643–1648 (2000).

-

Lautt, W. W. Insulin sensitivity in skeletal muscle regulated by a hepatic hormone, HISS. Can. J. Appl. Physiol. 30, 304–312 (2005).

-

Shimazu, T. Innervation of the liver and glucoregulation: Roles of the hypothalamus and autonomic nerves. Nutrition 12, 65–66 (1996).

-

Yamauchi, T., Iwai, M., Kobayashi, N. & Shimazu, T. Noradrenaline and ATP decrease the secretion of triglyceride and apoprotein B from perfused rat liver. Pflug. Arch. 435, 368–374 (1998).

-

Masahiro, O., Takeo, S., Keisuke, Y. & Terukazu, M. Hepatic branch vagotomy can suppress liver regeneration in partially hepatectomized rats. HPB Surg. 6, 277–286 (1993).

-

Oben, J. A. & Diehl, A. M. Sympathetic nervous system regulation of liver repair. Anat. Rec. Part Discov. Mol. Cell Evol. Biol. 280A, 874–883 (2004).

-

Jung, W.-C., Levesque, J.-P. & Ruitenberg, M. J. It takes nerve to fight back: The significance of neural innervation of the bone marrow and spleen for immune function. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 61, 60–70 (2017).

-

Nance, D. M. & Burns, J. Innervation of the spleen in the rat: Evidence for absence of afferent innervation. Brain Behav. Immun. 3, 281–290 (1989).

-

Cano, G., Sved, A. F., Rinaman, L., Rabin, B. S. & Card, J. P. Characterization of the central nervous system innervation of the rat spleen using viral transneuronal tracing. J. Comp. Neurol. 439, 1–18 (2001).

-

Bellinger, D. L., Lorton, D., Hamill, R. W., Felten, S. Y. & Felten, D. L. Acetylcholinesterase staining and choline acetyltransferase activity in the young adult rat spleen: Lack of evidence for cholinergic innervation. Brain, Behav., Immun. 7, 191–204 (1993).

-

Schäfer, M. K.-H., Eiden, L. E. & Weihe, E. Cholinergic neurons and terminal fields revealed by immunohistochemistry for the vesicular acetylcholine transporter. II. The peripheral nervous system. Neuroscience 84, 361–376 (1998).

-

Ackerman, K. D., Felten, S. Y., Dijkstra, C. D., Livnat, S. & Felten, D. L. Parallel development of noradrenergic innervation and cellular compartmentation in the rat spleen. Exp. Neurol. 103, 239–255 (1989).

-

Ackerman, K. D., Felten, S. Y., Bellinger, D. L. & Felten, D. L. Noradrenergic sympathetic innervation of the spleen: III. Development of innervation in the rat spleen. J. Neurosci. Res. 18, 49–54 (1987).

-

Mota, C. M. D. & Madden, C. J. Neural control of the spleen as an effector of immune responses to inflammation: mechanisms and treatments. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 323, R375–R384 (2022).

-

Nance, D. M. & Sanders, V. M. Autonomic innervation and regulation of the immune system (1987–2007). Brain Behav. Immun. 21, 736–745 (2007).

-

MacNeil, B. J., Jansen, A. H., Janz, L. J., Greenberg, A. H. & Nance, D. M. Peripheral endotoxin increases splenic sympathetic nerve activity via central prostaglandin synthesis. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 273, R609–R614 (1997).

-

Hu, X., Goldmuntz, E. A. & Brosnan, C. F. The effect of norepinephrine on endotoxin-mediated macrophage activation. J. Neuroimmunol. 31, 35–42 (1991).

-

Meltzer, J. C. et al. Stress-induced suppression of in vivo splenic cytokine production in the rat by neural and hormonal mechanisms. Brain Behav. Immun. 18, 262–273 (2004).

-

Lucin, K. M., Sanders, V. M., Jones, T. B., Malarkey, W. B. & Popovich, P. G. Impaired antibody synthesis after spinal cord injury is level dependent and is due to sympathetic nervous system dysregulation. Exp. Neurol. 207, 75–84 (2007).

-

Ueno, M., Ueno-Nakamura, Y., Niehaus, J., Popovich, P. G. & Yoshida, Y. Silencing spinal interneurons inhibits immune suppressive autonomic reflexes caused by spinal cord injury. Nat. Neurosci. 19, 784–787 (2016).

-

Wang, X. Bioartificial organ manufacturing technologies. Cell Transpl. 28, 5–17 (2018).

-

Li, X., Wen, L., Liu, J. & Wang, X. Three-dimensional printing-driving liver therapies. Curr. Med. Chem. 28, 6931–6953 (2021).

-

Song, J., Lv, B., Chen, W., Ding, P. & He, Y. Advances in 3D printing scaffolds for peripheral nerve and spinal cord injury repair. Int. J. Extrem. Manuf. 5, 032008 (2023).

-

Zhou, Z. et al. Engineering innervated musculoskeletal tissues for regenerative orthopedics and disease modeling. Small 20, e2310614 (2024).

-

Zhang, H., Zhao, Z. & Wu, C. Bioactive inorganic materials for innervated multi-tissue regeneration. Adv. Sci. 12, 2415344 (2025).

-

Kalyan, B. P. & Kumar, L. 3D Printing: Applications in tissue engineering, medical devices, and drug delivery. AAPS PharmSciTech 23, 92 (2022).

-

Moroni, L. et al. Biofabrication: A guide to technology and terminology. Trends Biotechnol. 36, 384–402 (2018).

-

Pillai, S., Munguia-Lopez, J. G. & Tran, S. D. Bioengineered salivary gland microtissues a review of 3D cellular models and their applications. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 7, 2620–2636 (2024).

-

Ma, L. et al. Current advances on 3D-bioprinted liver tissue models. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 9, e2001517 (2020).

-

Arakawa, C. et al. Biophysical and biomolecular interactions of malaria-infected erythrocytes in engineered human capillaries. Sci. Adv. 6, eaay7243 (2020).

-

Lam, E. H. Y., Yu, F., Zhu, S. & Wang, Z. 3D Bioprinting for next-generation personalized medicine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 6357 (2023).

-

Dubbin, K., Hori, Y., Lewis, K. K. & Heilshorn, S. C. Dual-stage crosslinking of a gel-phase bioink improves cell viability and homogeneity for 3D bioprinting. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 5, 2488–2492 (2016).

-

Lee, A. et al. 3D bioprinting of collagen to rebuild components of the human heart. Science 365, 482–487 (2019).

-

Grebenyuk, S. et al. Large-scale perfused tissues via synthetic 3D soft microfluidics. Nat. Commun. 14, 193 (2023).

-

Yao, Y., Coleman, H. A., Meagher, L., Forsythe, J. S. & Parkington, H. C. 3D Functional neuronal networks in free-standing bioprinted hydrogel constructs. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 12, e2300801 (2023).

-

Ma, J., Eglauf, J., Grad, S., Alini, M. & Serra, T. Engineering sensory ganglion multicellular system to model tissue nerveingrowth. Adv. Sci. 11, 2308478 (2024).

-

Wang, J. et al. Rational design and acoustic assembly of human cerebral cortex-like microtissues from hiPSC-derived neural progenitors and neurons. Adv. Mater. 35, e2210631 (2023).

-

Takahashi, H., Itoga, K., Shimizu, T., Yamato, M. & Okano, T. Human neural tissue construct fabrication based on scaffold-free tissue engineering. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 5, 1931–1938 (2016).

-

Bouyer, C. et al. A bio-acoustic levitational (BAL) assembly method for engineering of multilayered, 3D brain-like constructs, using human embryonic stem cell derived neuro-progenitors. Adv. Mater. 28, 161–167 (2016).

-

Qiu, B. et al. Bioprinting neural systems to model central nervous system diseases. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 1910250 (2020).

-

Yan, Y. et al. 3D bioprinting of human neural tissues with functional connectivity. Cell Stem Cell 31, 260–274.e7 (2024).

-