Introduction

RNA plays a crucial role in various biological and pathological processes. Given that over 70% of the human genome is transcribed into RNA, with only about 1.5% encoding proteins, targeting RNA as a therapeutic approach significantly expands the pharmaceutical potential of the human genome, providing valuable targets for basic research and drug development1,2. RNA-targeted degradation technologies can precisely treat diseases by selectively disrupting the expression of specific genes, minimizing damage to healthy cells, offering treatment options for patients unresponsive to traditional therapies. One commonly used strategy is RNA interference (RNAi), which degrades target RNAs in eukaryotes and holds a significant position in basic biological research and drug development3. However, while small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) used in RNAi typically range from 21 to 22 nucleotides in length, their specificity largely depends on a 2 to 8 nucleotide complementary sequence at the 5’ end. This reliance on short sequences raises concerns about off-target effects. Additionally, the double-stranded RNA used as precursors for siRNAs can trigger non-specific immune responses, such as interferon activation4,5,6. Consequently, there has been a long-standing pursuit of RNA-targeted degradation methods that offer greater accuracy and specificity.

A variety of methods have been developed recently to RNA-targeted degradation7,8. For example, ribonuclease targeting chimeras (RIBOTACs) combine small molecule drugs with RNA recognition elements, allowing for the selective targeting and degradation of specific RNA molecules to regulate gene expression9,10. By utilizing the cell’s natural RNA degradation pathways, RIBOTACs enable rapid reduction of target RNA levels. However, their development requires the design of small molecules that bind exclusively to the target RNA, making RIBOTACs more complex to create than oligonucleotide-based therapies and limiting their adaptability compared to programmable RNA degradation technologies. The clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-Cas system, especially Cas13, is notable for its role in bacterial defense against viruses. Cas13 activates its RNase activity by binding to guide RNA containing a 20-30 nucleotide spacer, enabling RNA cleavage11,12. Its high complementarity with target mRNA enhances specificity compared to traditional RNA interference methods. However, its application is challenged by potential non-specific cleavage, known as the “bystander RNA cleavage”, which can cause cytotoxicity and limit its ability to specifically knock down mRNA at the transcriptional level13,14. To address this, researchers developed catalytically inactive Cas13 (dCas13), which recognizes mRNA and inhibits translation initiation, allowing for gene silencing15. However, it still faces limitations in achieving complete RNA degradation, which may restrict its effectiveness for disrupting gene expression. Thus, a programmable method that can specifically, efficiently, and safely degrade targeted RNAs in mammalian cells is still in demand.

Lysosomes possess potent degradative capabilities, capable of breaking down a wide array of biomolecules such as proteins, DNA/RNA, lipids, and microbial pathogens. Chaperone-Mediated Autophagy (CMA) is a selective autophagy process that degrades specific intracellular proteins using lysosomes16,17. Proteins containing the CMA targeting motif (CTM) are recognized by chaperone proteins and transported to the lysosome for degradation. CMA plays a vital role in cellular stress responses, protein quality control, and metabolic regulation and is closely associated with various diseases18,19,20. So far, CMA has been developed as an effective means for protein degradation by selectively recognizing targets with specific amino acid sequences21,22. However, the capability of lysosomal degradation of nucleic acids through the CMA pathway has long been overlooked.

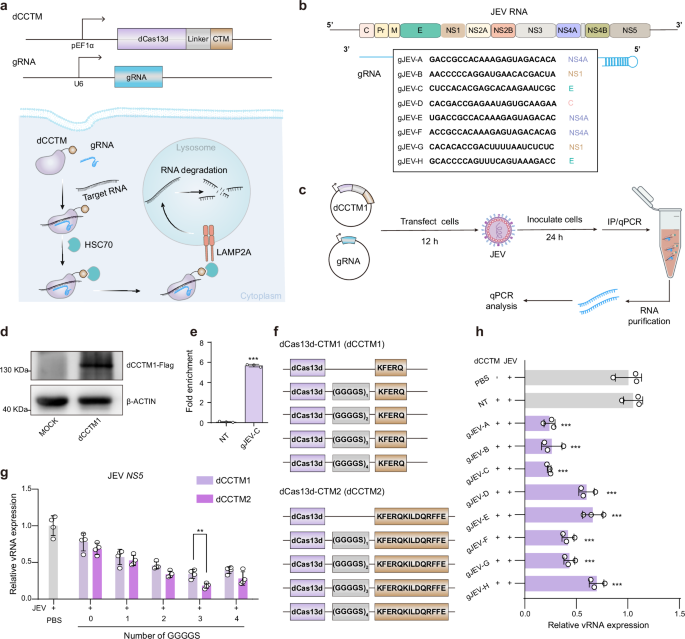

In this study, we utilize the characteristics of CMA and implement a protein engineering approach to create a versatile and programmable platform, dCas13d-directed chaperone-mediated autophagy (dCasCMA). This platform enables precise degradation of RNA by merging the accurate RNA-targeting ability of dCas13d with the effective degradation mechanisms of CMA pathway. The platform comprises a dual-component system of CTM-tagged dCas13d (dCCTM) and guide RNA (gRNA), which work together to target and degrade both endogenous and exogenous RNA (Fig. 1a). This process involves forming a complex with the target RNA, dCCTM, and gRNA, which is then delivered to the lysosome for RNA degradation via the CMA pathway. Furthermore, the dCasCMA platform can incorporate multiplexed effector guide array (MEGA) technology8, allowing for the simultaneous introduction of multiple gRNAs at once into cells. This combination effectively facilitates the concurrent degradation of various RNA targets in vivo and in vitro.

a Schematic of the dCasCMA system, in which dCas13d fused to a CMA-targeting motif (dCCTM) and guide RNA (gRNA) directs target RNA degradation via the chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA) pathway. Created in BioRender. Wen, H. (2025) https://BioRender.com/41b43vf. b Design of gRNAs targeting the genomic RNA of Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV). c. Experimental workflow for validating dCasCMA-mediated viral RNA (vRNA) degradation. The infected BHK cells expressing dCCTM1 with 1 GGGGS repeat and gRNA were subjected to FLAG immunoprecipitation, followed by quantitative PCR (qPCR) to quantify bound vRNA. Created in BioRender. Wen, H. (2025) https://BioRender.com/41b43vf. d WB analysis confirming the successful expression of dCCTM1 using FLAG antibodies. (n = 3, biological replicates). e qPCR analysis showing significant enrichment of vRNA in dCCTM1 pulldowns when using gJEV-C (n = 3, biological replicates), p < 0.0001. f Construction of dCCTM variants by fusing dCas13d to two distinct CTMs via GGGGS linkers of varying repeat numbers. g Expression levels of the vRNA in infected cells treated with dCCTM variants (100 nM) and gJEV-C plasmids, identifying dCas13d-(GGGGS)3-CTM2 as the optimal dCCTM structure. Primers targeting the NS5 genomic regions of vRNA (JEV NS5 primers) were used for the qPCR analysis (n = 4, biological replicates), p = 0.0036. h vRNA level in infected BHK cells treated with optimal dCCTM structure (dCas13d-(GGGGS)3-CTM2, 100 nM) and different gRNAs (n = 3, biological replicates). The dCCTM + NT group was used as a control. gJEV-A p < 0.0001; gJEV-B p < 0.0001; gJEV-C p < 0.0001; gJEV-D p < 0.0001; gJEV-E p < 0.0003; gJEV-F p < 0.0001; gJEV-G p < 0.0001; gJEV-H p = 0.001. Data represent mean ± SD. Statistical significance was determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test (e, g) or one-way ANOVA (h). **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Results

Development of a dCasCMA platform for RNA-targeted degradation

dRfxCas13d can achieve sustained, stable, and specific targeting of target RNA in mammalian cells without inducing cytotoxic effects associated with off-target cleavage15. The Lys-Phe-Glu-Arg-Gln (KFERQ, CTM1) sequence is recognized as a classic targeting motif for CMA pathway23. This sequence can be identified by heat shock chaperone proteins, such as heat shock cognate 70 kDa protein (HSC70), in the cytoplasm. Once recognized, the KFERQ-containing biomolecules are transported to the lysosome via lysosome-associated membrane protein 2 A (LAMP2A), facilitating their degradation within the lysosomal environment. Thus, we initially fused dRfxCas13d with KFERQ using a flexible linker (1 GGGGS repeat) to create a preliminary bifunctional fusion protein (dCCTM1), to achieve degradation of target RNAs by binding to the gRNA.

To evaluate the potential of dCasCMA as a programmable RNA degradation platform, we used Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV)-infected cells as a disease model. JEV is a single-stranded positive-sense RNA virus with an approximately 11 kb genome that encodes multiple structural and non-structural proteins24. We designed several gRNAs targeting distinct regions of the viral RNA (vRNA), covering various protein coding areas (Fig. 1b). BHK cells were co-transfected with dCCTM1-expression plasmids and gRNA constructs for 12 h prior to JEV infection, and vRNA levels were quantified by quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) after 24 h of infection using primers targeting the NS3, NS5, and E genomic regions. Notably, among the functional gRNAs, we observed comparable degradation efficiency across all targeted regions, demonstrating that the technology’s ability to degrade the target long-chain RNA effectively (Fig. 1c, Supplementary Fig. 1a). However, gRNA activity varied significantly, with some effectively mediating dCasCMA-dependent degradation of full-length JEV RNA while others showed minimal effects. This trend closely paralleled observations with wild-type (WT) Cas13, suggesting that dCCTM1 and WT Cas13d share similar gRNA sequence preferences (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Through systematic comparison of vRNA degradation efficiency, we identified gJEV-C as the top-performing gRNA which was used in the subsequent experiment (Supplementary Fig. 1a).

To further validate RNA targeting by the dCCTM1/gJEV-C complex, we performed immunoprecipitation (IP) assays using anti-FLAG antibodies to isolate dCCTM1-associated RNA complexes. Compared to control cells expressing non-targeting (NT) gRNAs, pulldown of dCCTM1 guided by gJEV-C showed a 5.6-fold enrichment of vRNA (Fig. 1d, e), demonstrating the high specificity of gJEV-C for its vRNA target. Additionally, to validate the specificity of dCCTM1-mediated RNA degradation, we generated a dCCTM1 mutant (mut-dCCTM1) by replacing its KFERQ sequence with KFERA25. This mutant failed to reduce vRNA levels (Supplementary Fig. 1c), thus confirming that targeting motif of dCCTM1 for CMA pathway is essential for targeted RNA degradation. Subsequently, we explored the effect of linker length on RNA degradation efficiency by engineering five dCCTM1 variants with 0 to 4 GGGGS repeats between dCas13d and the CTM domain (Fig. 1f). RNA levels were quantified 24 h post-infection, and qPCR assays showed that the dCCTM1/gRNA complexes without any GGGGS linkers displayed minimal degradation activity. Incrementally increasing the number of GGGGS repeats led to a gradual enhancement in RNA degradation efficiency, with the optimal performance observed at three GGGGS repeats. Further, inspired by reports that the KFERQKILDQRFFE (CTM2) motif enhances CMA pathway engagement25, we designed dCCTM2 variants with analogous linker configurations. Notably, the dCCTM2/gRNA complex recapitulated the linker-dependent pattern, exhibiting 1.2-fold greater degradation efficiency than its dCCTM1 counterpart when both contained three GGGGS repeats (Fig. 1g, Supplementary Fig. 1d-f). These results established CTM2 as the superior CMA-targeting module, leading us to select dCas13d-(GGGGS)₃-CTM2 (hereafter termed dCCTM) as the optimal configuration for all subsequent studies.

When paired with the same panel of gRNAs (as in Fig. 1b), the optimized dCCTM showed conserved gRNA sequence preferences similar to WT Cas13d, yet demonstrated significantly enhanced RNA degradation efficiency in each group compared to dCCTM1 (Fig. 1h). This indicated that the engineering process preserved the fundamental RNA recognition mechanisms while improving performance. Meanwhile, while dCas13 is known to inhibit translation initiation by binding start codons of target RNA15, our comparative analysis revealed that the dCasCMA system exhibits a fundamentally different mechanism of action. While both systems successfully target the open reading frame of vRNA using identical guide RNAs, only dCasCMA achieves significant viral RNA degradation (Supplementary Fig. 1g). This highlights its unique, translation-independent mechanism while maintaining target specificity, offering more complete RNA elimination. Moreover, the optimized dCCTM exhibits negligible cytotoxicity (Supplementary Fig. 1h), highlighting its therapeutic potential.

RNA degradation mechanism of the dCasCMA system

To further validate the degradation effect of the dCasCMA system on JEV RNA, we conducted a series of experiments. Immunostaining using anti-JEV E protein antibodies revealed reduced viral E protein expression in dCCTM/gJEV-C-treated cells (Fig. 2a, b, Supplementary Fig. 2a). Western blot (WB) analysis demonstrated that increasing concentrations of dCCTM/gJEV-C led to dose-dependent degradation of viral RNA (vRNA), as evidenced by the corresponding reduction in JEV E protein levels (Fig. 2c, d). Additionally, qPCR analysis targeting distinct coding regions (E, NS3, NS5) of the vRNA further confirmed significant reductions of the long-chain RNA in the dCCTM/gJEV-C treatment group (Supplementary Fig. 2b-d). Critically, virus titer assay demonstrated a notable decline in viral replication rates in virus-infected cells treated with dCCTM/gJEV-C (Fig. 2e). Collectively, these findings highlighted the strong antiviral capabilities of the dCasCMA system through efficient vRNA degradation and substantial inhibition of viral replication.

a Immunofluorescence images of JEV E protein in infected cells under different treatments. Scale bar, 20 μm. b Quantification analysis of the mean intensity of JEV E protein immunofluorescence under different conditions as in (a) (n = 5, biological replicates), p < 0.0001. c, d WB detection and quantification analysis of JEV E protein in infected cells under different treatments, 50 nM p < 0.0001; 100 nM p < 0.0001; 150 nM p < 0.0001. (n = 3, biological replicates). e Viral titers in supernatants from treated cells quantified by plaque assay 24 h post-infection, p = 0.001. (n = 3, biological replicates). f Colocalization of mNeongreen-labeled dCCTM/gJEV-C and Lysotracker red-stained lysosomes in BHK cells. Scale bar, 10 μm. (n = 3, biological replicates). g HCR-FISH visualization of JEV RNA (Cy3, Magenta) colocalized with EGFP-labeled LAMP1 (green). Scale bar, 5 μm. (n = 3, biological replicates). h vRNA levels (qPCR, JEV NS5 primer) in dCCTM/gJEV-C-treated infected cells with/without siLAMP2A-1 or siHSC70-3 knockdown. (gJEV-C vs. gJEV-C + siLAMP2A p = 0.0001; gJEV-C vs. gJEV-C + siHSC70 p = 0.0002). (n = 3, biological replicates). i, j vRNA and E protein levels in dCCTM/gJEV-C-transfected infected cells treated with or without QX77 (10 μM) and VER-15508 (0.5 μM), PBS vs. gJEV-C + VER-15508 p = 0.105; gJEV-C vs. gJEV-C + QX77 p = 0.0125; gJEV-C vs. gJEV-C + VER-15508 p < 0.0001. (n = 3, biological replicates). k Quantification analysis of JEV E protein expression levels shown in (j), PBS vs. gJEV-C + VER-15508 p = 0.0772; gJEV-C vs. gJEV-C + QX77 p = 0.004; gJEV-C vs. gJEV-C + VER-15508 p = 0.0002. (n = 3, biological replicates). Data represent mean ± SD. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA (d, h) or unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test (b, e, i and k). ns, not significant; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Subsequently, to validate the lysosome-dependent degradation mechanism, we transfected BHK cells with mNeonGreen-tagged dCCTM/gJEV-C, followed by LysoTracker staining 24 hours post-JEV infection. Confocal imaging revealed strong co-localization of the dCCTM/gJEV-C complex with lysosomes, whereas CTM2-deficient dCas13d failed to localize to lysosomes even when guided by gJEV-C (Fig. 2f, Supplementary Fig. 2e-g). This finding demonstrated that the incorporation of CTM2 effectively directs the dCas13d/gJEV-C complex to the lysosomal compartments. To further investigate whether JEV RNA is actively transported into lysosomes, we performed hybridization chain reaction (HCR) fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) to label the vRNA with Cy3 in cells and found significant co-localization of vRNA signals with EGFP-tagged lysosomal marker LAMP1 (lysosome-associated membrane protein 1) (Fig. 2g). This result strongly suggested that vRNA is internalized into lysosomes following dCCTM/gJEV-C targeting. Additionally, we extracted lysosomes from treated cells, degraded extralysosomal RNA with RNase A, and analyzed intralysosomal vRNA levels by PCR. The results showed that vRNA was detected within lysosomes in the dCCTM/gJEV-C-treated group after RNase A treatment. In contrast, no vRNA was found in lysosomes of JEV-infected cells treated with only RNase A treatment (Supplementary Fig. 2h), consistent with the existing reports that JEV RNA typically does not local within lysosomes26,27. These findings demonstrated that our engineered dCCTM/gJEV-C complex efficiently transports JEV RNA into lysosomal compartments. This unique capability underscores the role of dCCTM in mediating the targeted delivery of RNA into lysosomes.

To explore the role of the CMA pathway in RNA-specific degradation, we employed siRNA to suppress the expression of CMA pathway-associated proteins LAMP2A and HSC70 and evaluated the RNA degradation efficiency of the dCasCMA systems. Quantitative analysis revealed that siRNA-mediated knockdown of LAMP2A and HSC70 significantly impaired the ability of dCasCMA systems to degrade JEV RNA (Fig. 2h and Supplementary Fig. 3a, b). Furthermore, we treated cells with CMA pathway modulators, including the LAMP2A activator (QX77) and HSC70 inhibitor (VER-15508)28,29. qPCR analysis demonstrated that activation of the CMA pathway using QX77 enhanced the RNA degradation capacity of dCasCMA systems, while treatment with VER-15508 attenuated their degradation efficiency. Consistent with these RNA-level effects, WB analysis revealed corresponding changes in JEV E protein levels (Fig. 2i-k). These results demonstrated that dCasCMA specifically harnesses the CMA pathway for targeted RNA degradation, providing a mechanistic basis for its RNA-targeting capability.

To delineate the contribution of alternative lysosomal RNA degradation pathways, we also evaluated the involvement of RNautophagy and endosomal microautophagy (eMI) in the RNA degradation of dCasCMA system by knocking down key components of these pathways. Specifically, we targeted LAMP2C/SIDT2 for RNautophagy and VPS4 for eMI30,31,32. qPCR assays and confocal imaging confirmed that these knockdowns did not impair the antiviral activity or lysosomal localization of dCasCMA-targeted vRNA (Supplementary Fig. 3c-h). The strict dependence on dCCTM/gRNA for lysosomal targeting, combined with the persistence of RNA degradation despite inhibition of alternative pathways, further supports that the dCasCMA system primarily utilizes the CMA pathway for RNA degradation. These results highlighted the capability of our engineered system to selectively exploit the CMA pathway for programmable RNA degradation.

Endogenous mRNA degradation using dCasCMA system

To further validate the universality and flexibility of dCasCMA platform, we next applied it to target the degradation of endogenous mRNAs of interest. Currently, malignant tumors disrupt the immune cycle due to the high expression of PD-L1, which protects tumors from the attack of cytotoxic T cells33,34. Therefore, it is crucial to utilize the dCasCMA degradation system to determine whether it can effectively degrade Pd-l1 mRNA. To this end, we designed four gRNAs targeting Pd-l1 mRNA (Fig. 3a). After co-transfecting the dCCTM and gRNA plasmids into CT26 tumor cells, WB and qPCR results showed that the dCCTM/gRNA-treated groups effectively suppressed PD-L1 expression compared to that of treated by dCCTM/NT group. Based on these findings, we selected gPdl1-D as the optimal gRNA for further investigation of Pd-l1 mRNA degradation (Fig. 3b-d).

a Schematic of the gRNA design for targeting the Pd-l1 mRNA. b WB analysis of total PD-L1 levels in CT26 cells treated with dCCTM and different gRNAs after 36 hours. (n = 3, biological replicates). c Quantitative analysis of PD-L1 protein expression levels shown in (b), gPdl1-A p = 0.0004; gPdl1-B p = 0.0008; gPdl1-C p < 0.0001; gPdl1-D p < 0.0001. d qPCR analysis of Pd-l1 mRNA levels in CT26 cells 36 h after dCCTM/gRNA transfection, gPdl1-A p < 0.0001; gPdl1-B p < 0.0001; gPdl1-C p < 0.0001; gPdl1-D p < 0.0001. e Time-course comparison of Pd-l1 mRNA knockdown efficiency between dCCTM/gPdl1-D and siPdl1, (0 h p = 0.9761;36 h p = 0.5124; 48 h p = 0.4019; 60 h p = 0.9157). f Downregulation of metastasis-related mRNAs (Pik3, β-catenin, Wip, N-cadherin, Vimentin) following Pd-l1 mRNA degradation induced by dCCTM/gPdl1-D, (Pik3 p = 0.0015; β-catenin p = 0.005; Wip p = 0.0083; N-cadherin p = 0.0013; Vimentin p = 0.0005). g Schematic illustration of the wound-healing assay for studying the migration ability of the cells under different conditions. Created in BioRender. Wen, H. (2025) https://BioRender.com/41b43vf. h, i Confocal images and cell migration rates of CT26 cells treated with dCCTM/NT and dCCTM/gPdl1-D. Scale bar, 500 μm. (Mock vs. dCCTM + NT, p = 0.9593; Mock vs. dCCTM + gPdl1-D, p = 0.0004). j Relative NEAT1 RNA expression levels in cells transfected with plasmids expressing dCCTM/dCCTM-NCS proteins and the indicated gRNA, measured by qPCR, (dCCTM + NT vs. dCCTM + gNEAT1, p = 0.6466; dCCTM-NCS + NT vs. dCCTM-NCS + gNEAT1, p = 0.0001). Data represent mean ± SD (n = 3, biological replicates). Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA (c, d, h and j) or unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test (e, f). ns, not significant; **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The RNAi approach, particularly using siRNA, is currently considered the most common method for RNA degradation technique35. To evaluate the potential of the dCasCMA technology as an alternative, we compared its mRNA degradation efficiency to that of siRNA. Live cells were transfected with either Pd-l1 siRNA or dCCTM/gPdl1-D, and the levels of Pd-l1 mRNA were assessed after 36 h. Remarkably, the dCasCMA system achieved approximately 80% degradation activity in Pd-l1 mRNA compared to the non-treated group, demonstrating a degradation efficiency comparable to that of siRNA. Furthermore, the dCasCMA system maintained its effectiveness at 48 and 60 h post-transfection, consistently matching the performance of the siRNA approach (Fig. 3e). These findings highlight the potential of the dCasCMA system as a powerful tool for targeted degradation of endogenous Pd-l1 mRNA, offering an alternative to the well-established siRNA-based methods.

Further, we investigated the alterations in gene expression of downstream signaling pathways related to PD-L1 following the reduction of Pd-l1 mRNA at the transcriptomic level36,37. The qPCR results demonstrated that Pd-l1 mRNA knockdown effectively downregulated the mRNA expression levels of associated proteins, such as Phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (Pi3k), β-catenin, Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein-interacting protein (Wip), N-cadherin, and Vimentin (Fig. 3f). Given the role of PD-L1 in initiating gene expression related to epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and cellular movement38, we explored the potential impact of Pd-l1 mRNA degradation by the dCasCMA system on tumor cell migration. A wound healing assay was conducted, in which cells were treated with PBS (Mock), dCCTM/NT, or dCCTM/gPdl1-D (Fig. 3g). The results revealed that treatment with dCCTM/gPdl1-D significantly slowed down the wound closure rate compared to both Mock and NT groups (Fig. 3h, i), indicating that Pd-l1 mRNA degradation by the dCasCMA system impairs tumor cell migration. These results confirmed that dCasCMA system can successfully degrade the endogenous Pd-l1 mRNA and downregulate the related signaling pathways.

To enhance the ability of dCasCMA to target transcripts that are retained in the nucleus, we further developed an engineered variant named dCasCMA-NCS. This variant includes two nuclear localization signals (NLS) and one nuclear export signal (NES), a design inspired by the concepts previously reported39. Our results demonstrated that dCasCMA-NCS can achieve a higher degradation efficiency for nuclear NEAT1 compared to the original dCasCMA system (Fig. 3j). This improvement indicated that the nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling (NCS) system incorporated in dCasCMA-NCS is highly effective in degrading long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) that are enriched in the nucleus.

Multiplexed RNA degradation with dCasCMA system

Viral infections in cells can lead to a cascade of detrimental effects, including uncontrolled viral replication, excessive inflammatory responses, and ultimately, cell death and organ damage40 (Fig. 4a). Among the key players in this process are Z-conformation nucleic acid binding protein 1 (ZBP1) and stimulator of interferon genes (STING), two interferon-stimulated genes that have been implicated in the inflammatory storms associated with viral infections41,42. To effectively combat these pathogenic processes, a strategy capable of simultaneously targeting and degrading multiple RNAs within infected cells is highly desirable. The integration of multiplexed effector guide array technology with the dCasCMA system offers a promising approach to achieve concurrent regulation of multiple genes, potentially revolutionizing the field of genome editing and functional genomics8. Here, we investigated the ability of dCCTM combined with a multiplexed gRNA array to simultaneously inhibit the upregulation of JEV RNA, ZBP1, and STING, which were found to be elevated following JEV infection, as confirmed by qPCR analysis (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Fig. 4a).

a Schematic representation of the ZBP1 and STING signaling pathways activated by viral infection. Created in BioRender. Wen, H. (2025) https://BioRender.com/41b43vf. b Schematic showing the design of multiplexed gRNA expression arrays (gJZS) targeting JEV RNA, ZBP1 mRNA, and STING mRNA using the dCasCMA system. dCCTM processes the gRNA arrays into mature gRNAs for targeted RNA degradation. Created in BioRender. Wen, H. (2025) https://BioRender.com/41b43vf. c RNA expression levels in infected cells treated with dCCTM/gJZS. (vRNA p < 0.0001; ZBP1 p = 0.0008; STING p = 0.0001). d, e WB and quantitative analysis of protein expression levels of JEV E, ZBP1 and STING in infected cells treated with dCCTM/gJZS. (JEV E p = 0.0006; ZBP1 p = 0.006; STING p = 0.0002). f Downstream effects of the degradation of JEV RNA, ZBP1 and STING in infected cells treated with dCCTM/gJZS. The expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines (TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-1β, IL-18, CCL2, CCL4, CXCL9, and CXCL10) was significantly reduced, while the expression of the anti-inflammatory cytokine Il-10 was significantly increased. dCCTM/NT vs. dCCTM/gJZS (TNF-α p < 0.0001; IFN-γ p < 0.0001; IL-6 p < 0.0001; IL-1β p = 0.0002; IL-10 p = 0.0002; IL-18 p = 0.001; CCL2 p < 0.0001; CCL4 p < 0.0001; CXCL9 p = 0.002; CXCL10 p = 0.0003). Data are presented as means ± SD (n = 3, biological replicates). Statistical significance was determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test. **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We designed gRNAs targeting the mRNAs of ZBP1 and STING and conducted quantitative analysis to assess the mRNA degradation effects of dCasCMA within JEV-infected cells. Through this process, we identified the optimal gRNA sequences for degrading ZBP1 (gZBP1-B) and STING (gSTING-C) mRNAs (Supplementary Fig. 4b, c). Moreover, we observed a dose-dependent degradation of ZBP1 and STING mRNA with varying concentrations of dCCTM/gRNA treatment. To further investigate the impact of ZBP1 and STING pathway inhibition on downstream protein expression, we treated JEV-infected cells with dCCTM/gRNAs and evaluated the levels of relevant proteins. The results demonstrated that the degradation of ZBP1 mRNA led to a significant decrease in the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-6, and IL-1β, as well as chemokines such as CCL4 and CXCL9. Conversely, the expression of the anti-inflammatory cytokine Il-10 was notably upregulated (Supplementary Fig. 4d). Similarly, the suppression of STING expression leads to a notable decrease in the levels of several pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, such as TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-1β, IL-18, CCL2, and CXCL10 (Supplementary Fig. 4e). These results further support the efficacy of the dCasCMA technology in targeting and degrading diverse endogenous mRNAs.

Moreover, the CMA process plays a vital role in regulating protein integrity and maintaining cellular equilibrium under normal circumstances. In response to stress, CMA activity is significantly upregulated to swiftly degrade damaged proteins and restore cellular homeostasis23. To evaluate the effect of the dCasCMA technology on endogenous mRNA degradation under normal conditions, we transfected both infected and uninfected BHK cells with dCCTM and gRNA plasmids. Following a 36 h incubation period, qPCR analysis revealed a modest reduction in ZBP1 and STING mRNA levels in normal cells, whereas infected cells demonstrated a substantial decrease. These findings suggested that the dCasCMA platform effectively amplifies RNA degradation under stress conditions, underscoring its potential for targeted RNA degradation in pathological states (Supplementary Fig. 5a).

Subsequently, we designed a multiplexed gRNA expression array, named gJZS, for JEV RNA, ZBP1 mRNA, and STING mRNA (Fig. 4b). When combined with dCCTM, this array has the capacity to suppress the expression of viral proteins as well as ZBP1 and STING in live infected cells. To assess the degradation efficacy of this multiplexed approach, we quantified the expression levels of the three RNAs in the treatment groups at 24 h post-infection using qPCR. The results showed that dCCTM/gJZS effectively degrades JEV RNA and reduces mRNA levels of ZBP1 and STING compared to the NT group (Fig. 4c). WB experiments further verified that the dCasCMA system could effectively degradation of vRNA, ZBP1 mRNA and STING mRNA, as evidenced by the corresponding reduction in the expression of JEV E, ZBP1 and STING proteins (Fig. 4d, e). These findings demonstrated the practicality of employing the dCasCMA platform to simultaneously degrade multiple RNA targets in live cells.

To investigate the impact of dCCTM/gJZS treatment on the inflammatory response, we evaluated the expression levels of various intracellular inflammatory mediators. As expected, the results revealed that dCCTM/gJZS treatment led to a significant reduction in the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, such as TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-1β, IL-18, CCL2, CCL4, CXCL9, and CXCL10. These molecules are crucial in initiating and sustaining inflammatory processes, and their decreased expression indicates a substantial reduction in the inflammatory response following dCCTM/gJZS treatment. Remarkably, the study also found a significant increase in the expression of IL-10, a critical anti-inflammatory cytokine, in cells treated with dCCTM/gJZS (Fig. 4f). This observation further reinforces the idea that dCCTM/gJZS has a strong immunomodulatory effect by inhibiting pro-inflammatory signaling while simultaneously promoting the expression of anti-inflammatory factors.

To assess the therapeutic potential of the dCCTM/gJZS approach, we utilized the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK8) assay to evaluate its effects on cell viability. Our experimental results demonstrated that viral infection caused a significant reduction in cell survival, underscoring the harmful impact of viral infection on host cells. Remarkably, when virus-infected cells were subjected to dCCTM/gJZS treatment, we observed a notable restoration of cell viability, indicating that this strategy effectively attenuates the cytopathic effects triggered by viral infection (Supplementary Fig. 5b). These findings were further corroborated by the outcomes of live/dead double staining using Calcein AM/PI assays (Supplementary Fig. 5c), which consistently showcased the protective effects of dCCTM/gJZS treatment on virus-infected cells. Taken together, our data provided strong evidence that dCCTM/gJZS treatment effectively modulates the intracellular inflammatory milieu, thereby contributing to the resolution of inflammatory processes.

In vivo RNA degradation efficacy of dCasCMA system

To ultimately assess the in vivo efficacy of the dCasCMA platform against viral encephalitis, we encapsulated the dCCTM protein and gJZS within nanoliposomes (NLPs) to create NLP@dCCTM/gJZS for enhanced delivery, as previously reported43,44 (Supplementary Fig. 6a-e). To evaluate the safety of NLP@dCCTM/gJZS, mice were administered NLP@dCCTM/NT and NLP@dCCTM/gJZS via intracerebroventricular (ICV) injection. At 72 h post-injection, serum biochemical indexes were analyzed and major organs were collected for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. The results showed no abnormalities in the NLP@dCCTM/gJZS-treated group compared to the mock group, confirming the favorable biosafety profiles of NLP@dCCTM/gJZS (Supplementary Fig. 6f, g). We then established a mouse model of viral encephalitis by infecting mice with JEV via ICV injection. qPCR results showed significant upregulation of vRNA and Ifn-β mRNA post-infection on the third day (Supplementary Fig. 7). The NLP@dCCTM/gJZS treatment was administered at 6, 24, and 48 h post-infection, and the therapeutic effects on viral encephalitis were evaluated 72 h after infection45 (Fig. 5a). qPCR analysis revealed that the levels of JEV RNA, as well as Zbp1 and Sting mRNAs, were significantly reduced in the NLP@dCCTM/gJZS treatment group compared to the NLP@dCCTM/NT group (Fig. 5g). WB results further validated that the dCasCMA system effectively decreased the protein expression of JEV E, ZBP1, and STING in vivo (Fig. 5b, c). These findings demonstrated that the dCasCMA platform can successfully target and reduce the expression of both viral proteins and host factors associated with viral encephalitis in a mouse model.

a Flowchart of antiviral treatment with dCCTM/gJZS-loaded nanoliposomes (NLP@dCCTM/gJZS) in the mouse model of JEV infection.Created in BioRender. Wen, H. (2025) https://BioRender.com/41b43vf. b, c WB and quantification analysis of protein expressions of JEV E, ZBP1, and STING in infected mouse brains with NLP@dCCTM/gJZS treatments. (JEV E, p = 0.0019; ZBP1, p = 0.0016; STING, p = 0.0042). d Immunofluorescence images of JEV E protein in infected mouse brains treated with NLP@dCCTM/gJZS. Scale bar, 20 μm. e Quantitative analysis of immunofluorescence of JEV E proteins shown in (d), (n = 5, biological replicates), p < 0.0001. f H&E staining images in infected mouse brains with different treatments. Scale bar, 2 mm. The box regions were enlarged, with a scale bar of 500 μm. g mRNA levels of JEV RNA, Zbp1, Sting, and related cytokines/chemokines (Tnf-α, Ifn-γ, Il-6, Ifn-β, Ccl2, Il-1β, Cxcl9, Cxcl10, Il-18, Ccl4, and Il-10) in infected mouse brains under different treatments. NLP@dCCTM/NT vs. NLP@dCCTM/gJZS. (vRNA p < 0.0001; Zbp1 p = 0.0001; Sting p = 0.0008; Tnf-α p = 0.0001; Ifn-γ p < 0.0001; Il-6 p < 0.0001; Ifn-β p < 0.0001; Ccl2 p < 0.0001; Il-1β p = 0.0053; Cxcl9 p = 0.0029; Cxcl10 p = 0.0013; Il-18 p = 0.0006; Ccl4 p < 0.0018; Il-10 p = 0.0009). Data are presented as means ± SD (n = 3, biological replicates). Statistical significance was determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To further validate the therapeutic effects of NLP@dCCTM/gJZS on JEV infection, we performed immunostaining of the JEV E protein. Confocal imaging revealed that treatment with NLP@dCCTM/gJZS significantly reduced the viral load in brain tissue following infection (Fig. 5d, e). Additionally, we assessed the extent of brain inflammation in the Mock, NLP@dCCTM/NT + JEV, and NLP@dCCTM/gJZS + JEV treated groups using H&E staining. Our results showed marked cellular infiltration in the group treated with NLP@dCCTM/NT post viral challenge, indicating that JEV infection elicits a strong inflammatory response in the body. In sharp contrast, mice treated with NLP@dCCTM/gJZS exhibited a considerable decrease in inflammatory activity, along with a notable reduction in cell clustering (Fig. 5f). Additionally, the expression of downstream pro-inflammatory cytokines, including Tnf-α, Ifn-γ, Il-6, Ifn-β, Ccl2, Il-1β, Cxcl9, Cxcl10, Il-18 and Ccl4 was significantly reduced, while the expression of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 was markedly increased (Fig. 5g). These findings demonstrated the considerable effectiveness of our NLP@dCCTM/gJZS in suppressing viral replication and reducing inflammatory responses in vivo.

Collectively, these data provide compelling evidence that dCasCMA technology is a promising approach to inhibit viral replication and attenuate the associated inflammatory response. By targeting multiple key pathways involved in viral pathogenesis, this strategy offers a potential means to protect from the deleterious consequences of viral infection.

Discussion

In this study, we present dCasCMA, an adaptable platform for targeted RNA degradation. The system utilizes a dCas13d protein fused with a CTM (dCCTM) and a guide RNA (gRNA) to precisely recognize the target RNA and deliver it to the lysosome for selective degradation through the CMA pathway. Building upon the CRISPR-dCas13 framework, dCasCMA retains full programmability while exhibiting superior specificity compared to RNA interference. It achieves direct RNA degradation rather than merely suppressing translation. Furthermore, by incorporating a multiplexed gRNA expression array, the platform possesses the ability to concurrently degrade multiple RNA targets within live cells and in vivo settings. In summary, the dCasCMA technology addresses the shortcomings of current RNA degradation techniques, offering potential for both basic RNA research and the development of therapeutic strategies targeting pathogenic RNAs.

The dCasCMA platform represents a paradigm shift in RNA-targeted degradation by combining CRISPR-guided specificity with chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA) machinery. By fusing a CMA-targeting motif to catalytically inactive dCas13d, our system directs gRNA-bound RNAs to lysosomes for degradation. Mechanistic studies demonstrated that dCasCMA relies on CMA for its function. For instance, vRNA degradation was maintained even when RNautophagy (LAMP2C/SIDT2 knockdown) or eMI (VPS4 depletion) was disrupted (Fig. 2h-k and Supplementary Fig. 3). ZBP1 mRNA degradation was significantly impaired under lysosomal dysfunction induced by NH4Cl/bafilomycin A1 and in CMA-deficient or dCCTM mutants-treated cells, while it remained unaffected by deficiencies in eMI. Consistently, ZBP1 mRNA degradation was significantly impaired in CMA-deficient and dCCTM mutants-treated cells combined with NH4Cl (Supplementary Fig. 8a). These results underscore the critical dependence of dCasCMA on an intact CMA pathway and functional lysosomes, for efficient target RNA degradation. Further, RNA turnover assays using actinomycin D revealed a dramatic shortening of ZBP1 mRNA half-life from 12.73 hours in control cells to 4.30 hours in cells expressing dCCTM/gZBP1. In contrast, the half-life of ZBP1 mRNA in mut-dCCTM/gZBP1-treated cells (12.40 hours) remained comparable to the control (Supplementary Fig. 8b), directly confirming that dCCTM/gZBP1 accelerates the degradation of its target mRNA and resolving concerns about steady-state RNA level changes. Agarose gel electrophoresis and qPCR analysis of lysosomal extracts revealed a time-dependent decrease in detectable JEV RNA fragments (Supplementary Fig. 8c, d). This provides definitive experimental evidence that JEV RNA undergoes degradation within the lysosomal compartment following dCCTM/gJEV-C-mediated targeting. Additionally, comparative RNA-seq analysis revealed that dCasCMA exhibits significantly reduced off-target effects relative to wild-type Cas13 (Supplementary Fig. 8e, f), demonstrating its superior targeting precision by eliminating the collateral RNase activity inherent to native Cas13 systems.

The dCasCMA system represents an advancement in programmable RNA targeting, demonstrating broad versatility across viral and cellular transcripts. In antiviral applications, it achieves dual functionality by directly degrading JEV genomic RNA to effectively suppressing viral replication cycles, and simultaneously modulating host inflammatory responses through coordinated knockdown of ZBP1 and STING mRNAs (Fig. 4c-f). This multiplexing capacity enables comprehensive antiviral therapy addressing both pathogen clearance and immunopathology. The platform’s therapeutic potential extends to oncology, where Pd-l1 mRNA degradation in tumor cells to downregulate the related signaling pathways and further impair tumor migration capability. These diverse applications stem from dCasCMA’s unique capacity to target multiple RNA species, coupled with its compatibility with existing gRNA design frameworks.

The dCasCMA system features an intrinsic temporal regulation mechanism that offers significant advantages for therapeutic applications. Mechanistic studies demonstrate that the CTM domain facilitates autodegradation of the dCCTM protein through lysosomal targeting, as evidenced by colocalization imaging using dCCTM/NT gRNA controls (Supplementary Fig. 8g). Quantitative time-course analysis established that this CTM-mediated turnover produces a predictable pharmacokinetic profile: the system maintains optimal degradation activity (>90% target knockdown) within the 60 h, followed by a controlled attenuation to approximately 70% residual efficiency by 72 h (Supplementary Fig. 8h-j). This self-limiting property enables precise temporal regulation of therapeutic activity while preventing prolonged off-target effects. This predictable pharmacokinetic profile addresses a critical challenge in RNA therapeutics by enabling precise intervention windows. Notably, the system shows enhanced activity under pathological stress conditions where CMA components are naturally upregulated23, suggesting particular efficacy in disease microenvironments. Moreover, the engineered variant like dCCTM-NCS further expand the platform’s reach. This enables the system to target and degrade nuclear-retained lncRNAs, such as NEAT1 (Fig. 3j). Thus, the dCasCMA system may provide therapeutic avenues for a variety of RNA-disordered conditions.

In summary, dCasCMA addressed several critical challenges in RNA-targeted interventions while presenting opportunities for further optimization. The system’s minimal off-target effects and capacity for combinatorial targeting overcome key limitations of existing technologies. Although its current efficiency trails wild-type Cas13, strategic improvements in delivery approaches including optimized expression systems or controlled dosing regimens could enhance its durability and therapeutic potential. Most significantly, dCasCMA’s unique ability to simultaneously target pathogenic RNAs and modulate host pathways provides a promising approach to treating complex diseases where both infectious agents and dysregulated immune responses contribute to pathology. As such, this platform not only advances our fundamental understanding of RNA biology but also provides a versatile framework for developing next-generation RNA-targeted therapies.

Methods

Ethics statement

Female BALB/c mice (6-week-old) were obtained from Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). All experiments were conducted in accordance with the Chinese Regulations for the Administration of Affairs Concerning Experimental Animals and were approved by the guidelines set by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Nankai University (SYXK (Jin) 2019-0003). The mice were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions at maintained approximately 19–24 °C and 40–60% relative humidity, on a 12 h light/dark cycle with ad libitum access to food and water. The sex was not considered in either the experimental design or analysis, as the primary objective of this study was to demonstrate the methodological feasibility in an animal model.

Construction of plasmids

To construct the dCCTM1 and dCCTM2 plasmids, we fused the KFERQ (CTM1) and KFERQKILDQRFFE (CTM2) sequences with varying copies of the GGGGS linker to the C-terminus of dRfxCas13d (without NLS), which was then cloned into the pHAGE-EF1α-IRES vector. For the mutant dCCTM (mut-dCCTM) plasmid, we substituted the KFERQKILDQRFFE sequence in dCCTM with KFERAKILDARFFE25. To create the nucleus-targeted RNA degradation plasmid (dCCTM-NCS), we added two copies of NLS and one NES to the N-terminus of dCCTM. The WT RfxCas13d plasmid was obtained from MiaoLing Plasmid, China (P54820). All plasmid sequences are listed in Supplementary Data 1.

To generate gRNA expression constructs targeting JEV, Pd-l1, Zbp1, Sting, EGFP mRNA and NEAT1 RNA, we cloned sequence-specific guide RNAs into the dRfxCas13d crRNA backbone vector using T4 DNA ligase (Takara). All single-guide DNA oligonucleotides were synthesized and HPLC-purified by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai), with target sequences detailed in Supplementary Tables 1–3.

For multiplex targeting (gJZS construct), we designed a gRNA array containing three distinct guides, which was commercially synthesized (Sangon Biotech) and ligated into dRfxCas13d crRNA backbone vector using T4 DNA ligase (Takara). The array architecture and sequences are provided in Supplementary Table 4.

Cell culture and dCasCMA treatment

The BHK-21(GNHa10), CT26(TCM37), and HEK 293 T (GNHu44) cell lines were obtained from the Shanghai Cell Bank, Chinese Academy of Sciences. BHK-21 and 293 T cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM), while CT26 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium. All media were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and cells were incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO₂ atmosphere.

To investigate the mechanism of dCasCMA-mediated RNA degradation, BHK cells were seeded in 6-well plates. Cells were pre-treated with the chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA) regulator QX77 (10 μM) for 36 h, followed by transfection with plasmid combinations (dCCTM/NT or dCCTM/gJEV-C). One group transfected with dCCTM/gJEV-C was pre-treated with VER-15508 (0.5 μM) for 1 h before JEV virus (SA-14-14-2) infection. After 24 h of incubation, total protein and RNA were extracted for WB and qPCR analysis to assess RNA degradation.

To evaluate lysosomal pathway involvement, BHK cells were transfected with dCCTM/gZBP-B or dCCTM/NT for 12 h, then treated with 200 μM H₂O₂ to induce oxidative stress. Cells were subsequently incubated with 20 mM NH₄Cl or 50 mM bafilomycin A1 (lysosomal inhibitors) for 24 h. ZBP1 mRNA levels were analyzed by qPCR to determine the effect of lysosomal inhibition on RNA degradation.

To assess the role of lysosomal acidification in dCasCMA-mediated ZBP1 mRNA degradation under compromised autophagy pathways, BHK cells were plated in 6-well plates, transfected with siRNAs targeting CMA, eMI components or dCCTM mutants, followed by dCCTM/gZBP1-B plasmid transfection for 12 h. Cells were then exposed to 200 μM H₂O₂ (oxidative stress inducer) and co-treated with 20 mM NH₄Cl for 24 h. Total RNA was extracted for ZBP1 mRNA quantification by qPCR.

For ZBP1 mRNA decay kinetics, plasmid-transfected BHK cells were treated with 10 μg/mL actinomycin D (transcriptional inhibitor) for 0-12 h. RNA extracted at indicated timepoints underwent qPCR analysis, with mRNA half-lives calculated from exponential decay curves.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) assay

qPCR was used to quantify mRNA and vRNA expression levels. The BHK cells were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 2 × 10⁵ cells. At 80% confluence, cells were transfected with plasmids encoding dCCTM or WT RfxCas13d (100 nM) and gRNA (1.2 μg) using jetPRIME transfection reagent. After 12 h, cells were infected with JEV (MOI = 2) for 1 h, and collected 24 h post-infection. For CT26 and 293 T cells, seeded at 5 × 10⁵ cells per well, samples were collected 36 h post-transfection. Total RNA was extracted using the Total RNA Extractor (Sangon Biotech), reverse-transcribed to cDNA with a DNA Synthesis Kit (GenStar Biotech), and qPCR was performed using 2×RealStar Power SYBR qPCR Mix (GenStar Biotech). Relative expression levels were calculated using the 2−∆∆Ct method, with primer sequences listed in Supplementary Tables 5–8.

Western blot analysis

BHK cells were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 2 × 10⁵ cells. When cells reached 80% confluence, they were transfected with dCCTM and gRNA plasmids using jetPRIME reagent. After 12 h, cells were infected with JEV (MOI = 2) for 1 h and collected 24 h post-infection. For CT26 cells, cells were transfected with the dCCTM and gRNA for 36 h. For mouse brain tissue, samples were homogenized to prepare cell lysates. Protein was extracted using Radio Immunoprecipitation Assay Lysis buffer (RIPA) lysis buffer, and protein concentration was quantified via Bicinchoninic Acid Assay (BCA) assay. Protein samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes. Membranes were blocked with 5% milk for 1 hour, incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies (anti-JEV E, GeneTex, GTX125867, 1:2000; anti-Flag, Proteintech, 66008-4-Ig, 1:8000; anti-GAPDH, Bioss, bs-2188R, 1:5000; anti-β-ACTIN, Signalway Antibody, 52901, 1:5000; anti-PD-L1, Solarbio, K106509P, 1:1000; anti-ZBP1; Proteintech, 13285-1-AP, 1:4000; anti-Sting, Signalway Antibody, 41859-1, 1:4000), and then with secondary antibodies (HRP, Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG, Abbkine, A21020, 1:5000; HRP, Goat Anti-Mouse IgG, Abbkine, A21010, 1:5000) for 2 h. After washing with TBST, proteins were visualized using ECL reagents and imaged with a Bio-Rad ChemiDoc™ system.

Immunoprecipitation assay

Immunoprecipitation experiments to detect binding between dCCTM/gRNA complex and the target RNA were performed as previously described46. BHK cells were cultured in 6-well plates and transfected with 100 nM dCCTM1 (with 1 GGGGS repeat) and 1.2 μg of gJEV-C plasmid when they reached 80% confluence. After 12 h of transfection, the cells were infected with JEV virus and incubated for an additional 24 h. Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer with protease inhibitors and RNase inhibitors for 30 min, then centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was incubated with 25 μL Protein A + G agarose (Beyotime) beads and 1 μL anti-Flag tag (Proteintech) antibody at 4 °C for 12 h. Beads were collected, washed three times with RIPA buffer, and RNA was extracted from the precipitate. Purified RNA was reverse-transcribed to cDNA and quantified by qPCR using JEV NS5 primers.

Immunofluorescence staining

BHK cells were seeded in glass-bottom dishes (Cellvis) and cultured to 70% ~ 80% confluence. Cells were then transfected with different plasmid combinations, including dCCTM/NT and dCCTM/gJEV-C. 12 h post-transfection, JEV was added to the cells and incubated for 1 h. Subsequently, the supernatant was removed, and the cells were washed once with DMEM before continuing incubation. 24 h post-infection, immunofluorescence staining was performed. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 20 min, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 15 minutes, and washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline containing Tween-20 (PBST buffer). The cells were then blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 1 h and incubated with anti-JEV E (at a dilution of 1:300) antibody overnight at 4 °C. After washing three times with PBST, cells were incubated with a Dylight-649-labelled secondary antibody (Abbkine, 1:500) for 2 h. The nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 for 20 minutes before imaging.

Detecting vRNA in lysosomes by PCR

To determine whether vRNA was present inside the lysosomes, lysosomes were isolated from infected cells under different treatments using density gradient centrifugation with a lysosome extraction Kit (BestBio Biotech)30. Next, the lysosomes were incubated with RNase A (100 μg) for 30 min at 4 °C to degrade any RNA that might be surface-bound. Total RNA was then extracted from the lysosomes using TRIzol reagent, followed by reverse transcription into cDNA using a cDNA synthesis kit. The vRNA was amplified via PCR using a Master Mix, with NS5 primer listed in Supplementary Table 9. PCR products were resolved on a 1% agarose gel to visualize specific amplification bands.

To validate lysosomal degradation of JEV RNA, lysosomes were isolated from dCCTM/gJEV-C-transfected BHK cells (30 h/36 h), treated with RNase A, followed by TRIzol extraction of intralysosomal RNA. Equal amounts RNA was reverse transcribed, and PCR-amplified using JEV-specific primers (Primer 1 amplified a 181-bp Fragment 1, Primer 2 amplified a 226-bp Fragment 2). The copy numbers of JEV RNA added to the culture supernatant at t = 0 h serves as a positive control. Similarly, we examined the number of copies of viral RNA per μL of extracted RNA in lysosomes after transfection with dCCTM/gJEV-C for different times using absolute quantification for qPCR. The primers are listed in Supplementary Table 9.

Fluorescence imaging for colocalization analysis

To investigate whether the designed dCCTM/gRNA complex enters lysosomes via chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA), cells were transfected with various plasmid combinations, including dCas13d-mNeonGreen/gJEV-C and dCCTM-mNeonGreen/gJEV-C. 12 h post-transfection, cells were infected with the virus. Subsequently, cells were stained with LysoTracker Red (Beyotime) for 30 min and washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) prior to imaging.

To further confirm that the dCasCMA approach directs target RNA into lysosomes, colocalization analysis was performed. Cells were transfected with EGFP-tagged LAMP1 (lysosomal marker) and dCCTM/gJEV-C plasmids for 12 h, followed by JEV infection. Post-infection, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA, 15 min, RT), washed 3 times with PBS, and permeabilized with 70% ethanol (−20 °C, overnight). Cells were then incubated in hybridization buffer (2× SSC, 10% deionized formamide, 37 °C, 30 min), and incubated with HCR initiator probes (37 °C, 6 h). Unbound probes were removed by washing (5× SSC + 0.1% Tween-20, 3 times). Amplification was performed in 2× SSC buffer containing 10% dextran sulfate and 1% Tween-20 (37 °C, 30 min). Pre-annealed HCR hairpins (H1 + Cy3-labeled H2, denatured at 95 °C for 90 s and cooled to RT) were added and incubated (37 °C, 12 h). Final washes (5× SSC + 0.1% Tween-20, 3 times) preceded imaging. Primer sequences are provided in Supplementary Table 10.

To demonstrate that vRNAs degraded by dCCTM/gJEV-C enter lysosomes via the LAMP2A-HSC70 pathway, colocalization analysis between vRNA, lysosomes, and dCCTM was performed. Briefly, BHK cells were seeded in 6-well plates and transfected with siSIDT2-2 or siLAMP2C-2 for 36 h, followed by transfection with mCherry-tagged Lamp1 and dCCTM-mNeonGreen/gJEV-C plasmids for 12 h. Cells were then infected with JEV. vRNA staining was performed as described above, with Cy5-labeled HCR probes used in this step.

Confocal images were obtained with a spinning disk confocal microscope equipped with an Olympus IX 81 microscope, a Nipkow disk type confocal unit (CSU-X1, Yokogawa) and an EMCCD (Andor iXon Ultra 897 detector). For imaging, mNeonGreen/EGFP was excited at λex = 488 nm with emission detected at λem = 525/50 nm, LysoTracker Red/Cy3/mCherry was excited at λex = 561 with emission detected λem = 617/73 nm, while Cy5 was excited at λex = 640 with emission detected λem = 685/40 nm. The Pearson’s correlation coefficient was calculated for the two separate channel signals per cell using the Coloc 2 plugin in Fiji.

Virus titration assay

The viral titer was determined using the standard plaque assay. Briefly, cells were inoculated at a density of 1 × 104 cells per well in 24-well plates. Once the cells reached approximately 80% confluence, serial 10-fold dilutions of each sample were prepared, and 200 μL of the diluted virus was added to each well. The cells were incubated at 37 °C for 1 h, with gentle shaking every 15 min to enhance viral adsorption. Following this incubation, the medium was removed, and the cells were cultured in a 1:1 mixture of 2× DMEM (Invitrogen) and 2% methylcellulose (HEOWNS) for 72 hs at 37 °C. Afterward, the cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde for 24 h and stained with 1% crystal violet for 12 h. Plaques were observed and counted to determine the viral titer.

siRNA knockdown assay

Cells were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 2 × 10^5 cells per well. Transfection was performed using the jetPRIME reagent with non-targeting siRNAs as the control (siNC), siHSC70, siLAMP2A, siLAMP2C, siSIDT2, or siVPS4. Cells were collected 36 h post-transfection, and mRNA expression levels were assessed by qPCR. The siRNA with the highest knockdown efficiency was selected for further optimization (Supplementary Fig. 3a-d and f). Based on these results, siHSC70-3, siLAMP2A-1, siLAMP2C-2, siSIDT2-2, and siVPS4-1 were chosen for subsequent experiments. To investigate the effect of these protein knockdowns on dCasCMA-mediated RNA degradation, BHK cells were seeded in 6-well plates and transfected with the selected siRNAs. For degradation of vRNA, cells were then cotransfected with dCCTM/gJEV-C plasmids and infected with JEV for 24 h. The cells were transfected with dCCTM/gZBP1-B plasmid for 36 h for degradation of ZBP1 mRNA under oxidative stress. Total protein and RNA were extracted for WB and qPCR analysis. The relevant sequences are provided in Supplementary Table 11.

Wound healing assay

To investigate cell migration, CT26 cells were seeded in 6-well plates and cultured until they reached 80% confluency. The cells were transfected with dCCTM/gPdl1-D or dCCTM/NT plasmids. After 24 h of transfection, a straight line was scratched across the center of each well using a pipette tip to create a “scratch” in the cell monolayer. Images were immediately captured to document the initial wound area. The cells were then incubated for an additional 24 h, after which the scratch areas were photographed again. The rate of cell migration was quantitatively analyzed.

Cell viability

Cells were inoculated in 96-well plates and transfected with different plasmid combinations as described. The cells were infected with the virus. Cell viability was then measured using the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK8) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Abbkine Technology Co., Ltd.). Briefly, CCK8 was mixed with DMEM at a 1:10 (v/v), and 100 μL of the mixture was added to each well, the cells were incubated at 37 °C for 1 h, the optical density (OD) values were measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader to assess cell viability. The following formula was used to calculate the cell viability: Cell viability (%) = (ODtreated – ODbackground)/ (ODmock − ODbackground) × 100%.

Calcein AM/PI staining

Cells were seeded in 24-well plates and transfected separately with different plasmid combinations. Cells were infected with JEV. Cell viability was measured using Calcein AM/PI staining reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The living cells are stained green with Calcein AM, while the nuclei of dead cells are stained red with PI. Briefly, cells were washed three times with PBS, and stained with Calcein AM/PI for 30 min, and then washed three times with PBS, Fluorescent images were captured.

Expression and purification of proteins

The expression and purification of dCCTM proteins were performed as previously described47,48. Briefly, the plasmid encoding His-tagged dCCTM was transformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3, from Sangon Biotech) cells, which were then plated on LB agar supplemented with kanamycin and incubated at 37 °C for 12–16 h. Monoclonal colonies were subsequently picked and cultured in LB medium containing kanamycin to expand the culture. When the optical density (OD) of the culture reached 0.6–0.8, 0.1 mM IPTG was added, and the cells were incubated at 19 °C for an additional 14 h. After incubation, the cells were harvested and resuspended by vertexing in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 12 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 0.5 M NaCl, pH 7.9). The cells were then sonicated and centrifuged to collect the supernatant. The dCCTM protein was purified by incubating the supernatant with Ni-NTA-Agarose resin at 4 °C for 2 h, followed by elution of the protein. The protein concentration was determined using a BCA assay, and its purity was assessed by SDS-PAGE (Supplementary Fig. 6a).

Preparation and characterization of NLP@ dCCTM/gJZS

The nonoliposomes (NLPs) were prepared using the hydrated film method, incorporating a lipid mixture of 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC), sphingomyelin (SM), cholesterol (Chol), monosialotetrahexosylganglioside (GM1), and 1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium propane (DOTAP)43,44,49,50. Briefly, these lipids were added proportionally (POPC/SM/Chol/GM1/DOTAP = 31.5/25.5/25.5/2.5/15 mol%) to a round-bottomed flask, and then the solvent was dried by vertexing to form a homogeneous film. Subsequently, the films were hydrated using 1 mL of PBS buffer and shaken for 2 h to obtain empty liposome suspensions. This suspension was subsequently filtered through polycarbonate membrane and the suspension was squeezed back and forth 21 times through two glass syringes attached to a squeezer to ensure thorough filtration and homogenization. To prepare dCCTM-loaded nonoliposomes (NLP@dCCTM), the lipid film was dissolved in a solution containing dCCTM proteins. The formulation was fine-tuned by varying the ratio of dCCTM proteins to lipids, resulting in a final lipid-to-protein ratio of 40:1 (m/m) (Supplementary Fig. 6b).

To prepare NLP@dCCTM/gJZS complexes, the gJZS used in vivo were synthesized using the T7 high-yield RNA synthesis kit. Cationically charged liposomes were combined with anionically charged gRNA, resulting in the formation of NLP@dCCTM/gJZS complexes through electrostatic interactions. Briefly, the NLP@dCCTM liposomes were added to the gJZS solution, and the mixture was incubated at 25 °C on an oscillator for 30 minutes to facilitate complex formation. Following this, 2% glycerol was added to each sample, and the complexes were loaded into the wells of an agarose gel. Agarose gel electrophoresis (2% agarose in 1 × TAE buffer, w/v) was performed at a constant voltage of 100 V. After electrophoresis, the gel was imaged to visualize the results. The images indicated that almost all gJZS were successfully loaded into the NLP@dCCTM at a ratio of 20:1 (NLP@dCCTM to gJZS, w/w), with free gJZS serving as a control (Supplementary Fig. 6c).

The NLPs and NLP@dCCTM/gJZS were characterized using dynamic light scattering (DLS) to determine their hydrodynamic size and surface charge. The NLPs exhibited an average diameter of approximately 67.2 nm and a surface charge of +12.0 mV. In contrast, the NLP@ dCCTM/gJZS liposomes had a diameter of 71.1 nm and a surface charge of +1.9 mV (Supplementary Fig. 6d, e).

In vivo therapeutic efficacy assay

For JEV infection, mice were anesthetized, and JEV was injected into the lateral ventricle of the brain. The injection coordinates relative to the bregma were 1.5 mm left, 0.6 mm posterior, and 2.0 mm depth. The virus was administered at a concentration of 108 PFU/mL, with a volume of 10 μL. Mice were then randomly divided into two groups and subjected to dCasCMA treatment (10 μM dCCTM protein and 2.5 μM gRNA) via intracerebroventricular (ICV) injection, and ICV administration were applied as previously described in the literature51,52. Brain tissues were collected 72 h post-infection for subsequent analysis.

Brain tissue homogenates were prepared using an automatic homogenizer. Total RNA was extracted from the homogenates using TRIzol reagent, following the manufacturer’s instructions, for subsequent qPCR analysis. Proteins were extracted using RIPA lysis buffer for WB analysis. For safety assessment, mice were administered NLP@dCCTM/NT and NLP@dCCTM/gJZS via ICV injection. Major organs (hearts, spleens, livers, lungs, and kidneys) were collected 72 h post-administration. The organs were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, followed by dehydration, embedding, sectioning, and staining with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for histological examination. Serum biochemical indexes were analyzed to evaluate organ function. Specifically, hepatic function was assessed by measuring alanine aminotransferase (ALT), renal function by blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine (CREA), and cardiac function by lactate dehydrogenase (LDH).

RNA-seq analysis

To assess the transcriptome-wide targeting specificity of WT Cas13d and dCCTM, 293 T cells were transfected with constructs expressing either WT Cas13d or dCCTM, each paired with EGFP-targeting gRNAs or non-targeting (NT) gRNA, followed by RNA-Seq analysis performed by Tsingke Biotechnology Co., Ltd (Beijing, China). The sequencing data were analyzed using iDEP 2.01 (http://bioinformatics.sdstate.edu/idep/) for functional enrichment, with differentially expressed genes identified using stringent thresholds (adjusted P-value < 0.05 and absolute fold change ≥ 1.5) to evaluate potential off-target effects.

Statistics and reproducibility

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 8.0 software. All data were presented as mean ± SD. Biological replicates in this work were performed at least three times. Statistical significance was determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test or unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. The thresholds for statistical significance were set as follows: ns (non-significant), p > 0.05; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.