Data availability

Raw data generated during the present study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request. The analyzed data are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14880024 (ref. 82). Data supporting the findings of this study are included within this paper and its Supplementary Information files. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

All computer code and customized software generated during and/or used in the present study are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14880024 (ref. 82).

References

-

Lebedev, M. A. & Nicolelis, M. A. L. Brain–machine interfaces: past, present and future. Trends Neurosci. 29, 536–546 (2006).

-

Serino, A. et al. Sense of agency for intracortical brain–machine interfaces. Nat. Hum. Behav. 6, 565–578 (2022).

-

Tang, X., Shen, H., Zhao, S., Li, N. & Liu, J. Flexible brain–computer interfaces. Nat. Electron 6, 109–118 (2023).

-

O’Doherty, J. E. et al. Active tactile exploration using a brain–machine–brain interface. Nature 479, 228–231 (2011).

-

Flesher, S. N. et al. A brain-computer interface that evokes tactile sensations improves robotic arm control. Science 372, 831–836 (2021).

-

Rapeaux, A. B. & Constandinou, T. G. Implantable brain machine interfaces: first-in-human studies, technology challenges and trends. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 72, 102–111 (2021).

-

Shin, G. et al. Flexible near-field wireless optoelectronics as subdermal implants for broad applications in optogenetics. Neuron 93, 509–521 (2017).

-

Yang, Y. et al. Wireless multilateral devices for optogenetic studies of individual and social behaviors. Nat. Neurosci. 24, 1035–1045 (2021).

-

Ausra, J. et al. Wireless, battery-free, subdermally implantable platforms for transcranial and long-range optogenetics in freely moving animals. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2025775118 (2021).

-

Yang, Y. et al. Preparation and use of wireless reprogrammable multilateral optogenetic devices for behavioral neuroscience. Nat. Protoc. 17, 1073–1096 (2022).

-

Wu, Y. et al. Wireless multi-lateral optofluidic microsystems for real-time programmable optogenetics and photopharmacology. Nat. Commun. 13, 5571 (2022).

-

Marshel, J. H. et al. Cortical layer–specific critical dynamics triggering perception. Science 365, eaaw5202 (2019).

-

Robinson, N. T. M. et al. Targeted activation of hippocampal place cells drives memory-guided spatial behavior. Cell 183, 1586–1599 (2020).

-

Gill, J. V. et al. Precise holographic manipulation of olfactory circuits reveals coding features determining perceptual detection. Neuron 108, 382–393 (2020).

-

Carrillo-Reid, L., Han, S., Yang, W., Akrouh, A. & Yuste, R. Controlling visually guided behavior by holographic recalling of cortical ensembles. Cell 178, 447–457 (2019).

-

Oldenburg, I. A. et al. The logic of recurrent circuits in the primary visual cortex. Nat. Neurosci. 27, 137–147 (2024).

-

Adesnik, H. & Abdeladim, L. Probing neural codes with two-photon holographic optogenetics. Nat. Neurosci. 24, 1356–1366 (2021).

-

Bollmann, Y. et al. Prominent in vivo influence of single interneurons in the developing barrel cortex. Nat. Neurosci. 26, 1555–1565 (2023).

-

Chong, E. et al. Manipulating synthetic optogenetic odors reveals the coding logic of olfactory perception. Science 368, eaba2357 (2020).

-

Pinto, L. & Dan, Y. Cell-type-specific activity in prefrontal cortex during goal-directed behavior. Neuron 87, 437–450 (2015).

-

Pinto, L. et al. Task-dependent changes in the large-scale dynamics and necessity of cortical regions. Neuron 104, 810–824 (2019).

-

Pinto, L., Tank, D. W. & Brody, C. D. Multiple timescales of sensory-evidence accumulation across the dorsal cortex. eLife 11, e70263 (2022).

-

Cox, J. & Witten, I. B. Striatal circuits for reward learning and decision-making. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 20, 482–494 (2019).

-

Ouyang, W. et al. A wireless and battery-less implant for multimodal closed-loop neuromodulation in small animals. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 7, 1252–1269 (2023).

-

Stujenske, J. M., Spellman, T. & Gordon, J. A. Modeling the spatiotemporal dynamics of light and heat propagation for in vivo optogenetics. Cell Rep. 12, 525–534 (2015).

-

Owen, S. F., Liu, M. H. & Kreitzer, A. C. Thermal constraints on in vivo optogenetic manipulations. Nat. Neurosci. 22, 1061–1065 (2019).

-

Wang, Q. et al. The Allen Mouse Brain Common Coordinate Framework: a 3D reference atlas. Cell 181, 936–953 (2020).

-

Klapoetke, N. C. et al. Independent optical excitation of distinct neural populations. Nat. Methods 11, 338–346 (2014).

-

O’Shea, D. J. & Shenoy, K. V. ERAASR: an algorithm for removing electrical stimulation artifacts from multielectrode array recordings. J. Neural Eng. 15, 026020 (2018).

-

Nakayama, H., Gerkin, R. C. & Rinberg, D. A behavioral paradigm for measuring perceptual distances in mice. Cell Rep. Methods 2, 100233 (2022).

-

Harris, K. D. & Mrsic-Flogel, T. D. Cortical connectivity and sensory coding. Nature 503, 51–58 (2013).

-

Leech, R. et al. Variation in spatial dependencies across the cortical mantle discriminates the functional behaviour of primary and association cortex. Nat. Commun. 14, 5656 (2023).

-

Paolino, A. et al. Non-uniform temporal scaling of developmental processes in the mammalian cortex. Nat. Commun. 14, 5950 (2023).

-

Levi, A. J., Yates, J. L., Huk, A. C. & Katz, L. N. Strategic and dynamic temporal weighting for perceptual decisions in humans and macaques. eNeuro 5, ENEURO.0169–18.2018 (2018).

-

Hyafil, A. et al. Temporal integration is a robust feature of perceptual decisions. eLife 12, e84045 (2023).

-

Resulaj, A., Ruediger, S., Olsen, S. R. & Scanziani, M. First spikes in visual cortex enable perceptual discrimination. eLife 7, e34044 (2018).

-

Nienborg, H. & Cumming, B. G. Decision-related activity in sensory neurons reflects more than a neuron’s causal effect. Nature 459, 89–92 (2009).

-

Weber, A. I. et al. Spatial and temporal codes mediate the tactile perception of natural textures. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 17107–17112 (2013).

-

Gavornik, J. P. & Bear, M. F. Learned spatiotemporal sequence recognition and prediction in primary visual cortex. Nat. Neurosci. 17, 732–737 (2014).

-

Baker, C. A., Elyada, Y. M., Parra, A. & Bolton, M. M. Cellular resolution circuit mapping with temporal-focused excitation of soma-targeted channelrhodopsin. eLife 5, e14193 (2016).

-

Daigle, T. L. et al. A suite of transgenic driver and reporter mouse lines with enhanced brain-cell-type targeting and functionality. Cell 174, 465–480 (2018).

-

Sridharan, S. et al. High-performance microbial opsins for spatially and temporally precise perturbations of large neuronal networks. Neuron 110, 1139–1155 (2022).

-

Kim, C. K., Adhikari, A. & Deisseroth, K. Integration of optogenetics with complementary methodologies in systems neuroscience. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 18, 222–235 (2017).

-

Ben-Simon, Y. et al. A suite of enhancer AAVs and transgenic mouse lines for genetic access to cortical cell types. Cell 188, 3045–3064 (2025).

-

Shin, H. et al. Transcranial optogenetic brain modulator for precise bimodal neuromodulation in multiple brain regions. Nat. Commun. 15, 10423 (2024).

-

McCue, A. C. & Kuhlman, B. Design and engineering of light-sensitive protein switches. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 74, 102377 (2022).

-

Duncan, J. Selective attention and the organization of visual information. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 113, 501–517 (1984).

-

Lemus, L., Hernández, A., Luna, R., Zainos, A. & Romo, R. Do sensory cortices process more than one sensory modality during perceptual judgments? Neuron 67, 335–348 (2010).

-

O’Riordan, M. & Passetti, F. Discrimination in autism within different sensory modalities. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 36, 665–675 (2006).

-

Mondor, T. A. & Amirault, K. J. Effect of same- and different-modality spatial cues on auditory and visual target identification. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 24, 745–755 (1998).

-

Karlin, L. & Mortimer, R. G. Effect of verbal, visual, and auditory augmenting cues on learning a complex motor skill. J. Exp. Psychol. 65, 75–79 (1963).

-

Niyo, G., Almofeez, L. I., Erwin, A. & Valero-Cuevas, F. J. A computational study of how an α- to γ-motoneurone collateral can mitigate velocity-dependent stretch reflexes during voluntary movement. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2321659121 (2024).

-

Berry, J. A., Marjaninejad, A. & Valero-Cuevas, F. J. Edge computing in nature: minimal pre-processing of multi-muscle ensembles of spindle signals improves discriminability of limb movements. Front. Physiol. 14, 1183492 (2023).

-

Cascio, C. J. & Sathian, K. Temporal cues contribute to tactile perception of roughness. J. Neurosci. 21, 5289–5296 (2001).

-

Hirsh, I. J. Auditory perception of temporal order. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 31, 759–767 (1959).

-

Greenspon, C. M., Shelchkova, N. D., Hobbs, T. G., Bensmaia, S. J. & Gaunt, R. A. Intracortical microstimulation of human somatosensory cortex induces natural perceptual biases. Brain Stimul. 17, 1178–1185 (2024).

-

Sahel, J.-A. et al. Partial recovery of visual function in a blind patient after optogenetic therapy. Nat. Med. 27, 1223–1229 (2021).

-

Drew, L. Restoring vision with optogenetics. Nature 639, S7–S9 (2025).

-

Taal, A. J. et al. Optogenetic stimulation probes with single-neuron resolution based on organic LEDs monolithically integrated on CMOS. Nat. Electron 6, 669–679 (2023).

-

Wang, Y., Garg, R., Cohen-Karni, D. & Cohen-Karni, T. Neural modulation with photothermally active nanomaterials. Nat. Rev. Bioeng. 1, 193–207 (2023).

-

Saunders, J. L., Ott, L. A. & Wehr, M. AUTOPILOT: automating experiments with lots of Raspberry Pis. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/807693 (2019).

-

Lu, L., Leanza, S. & Zhao, R. R. Origami with rotational symmetry: a review on their mechanics and design. Appl. Mech. Rev. 75, 050801 (2023).

-

He, D., Malu, D. & Hu, Y. A Comprehensive review of indentation of gels and soft biological materials. Appl. Mech. Rev. 76, 050802 (2024).

-

Yan, P., Huang, H., Meloni, M., Li, B. & Cai, J. Mechanical properties inside origami-inspired structures: an overview. Appl. Mech. Rev. 77, 011001 (2025).

-

Christensen, R. M. Review of the basic elastic mechanical properties and their realignment to establish ductile versus brittle failure behaviors. Appl. Mech. Rev. 75, 030801 (2023).

-

Huang, Y. et al. Microfluidic serpentine antennas with designed mechanical tunability. Lab Chip 14, 4205–4212 (2014).

-

Wu, M. et al. Analysis and management of thermal loads generated in vivo by miniaturized optoelectronic implantable devices. Device https://doi.org/10.1016/j.device.2025.100898 (2025).

-

Fang, Q. & Boas, D. A. Monte Carlo simulation of photon migration in 3D turbid media accelerated by graphics processing units. Opt. Express 17, 20178 (2009).

-

Zhang, H. et al. Analytical solutions for light propagation of LED. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 122, e2508163122 (2025).

-

Deshpande, V. S. & McMeeking, R. M. Models for the interplay of mechanics, electrochemistry, thermodynamics, and kinetics in lithium-ion batteries. Appl. Mech. Rev. 75, 010801 (2023).

-

Zhao, W., Liu, L., Lan, X., Leng, J. & Liu, Y. Thermomechanical constitutive models of shape memory polymers and their composites. Appl. Mech. Rev. 75, 020802 (2023).

-

Kwon, K. et al. Wireless, soft electronics for rapid, multisensor measurements of hydration levels in healthy and diseased skin. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2020398118 (2021).

-

Wu, M. et al. Attenuated dopamine signaling after aversive learning is restored by ketamine to rescue escape actions. eLife 10, e64041 (2021).

-

Wu, M., Minkowicz, S., Dumrongprechachan, V., Hamilton, P. & Kozorovitskiy, Y. Ketamine rapidly enhances glutamate-evoked dendritic spinogenesis in medial prefrontal cortex through dopaminergic mechanisms. Biol. Psychiatry 89, 1096–1105 (2021).

-

Xiao, L., Priest, M. F., Nasenbeny, J., Lu, T. & Kozorovitskiy, Y. Biased oxytocinergic modulation of midbrain dopamine systems. Neuron 95, 368–384 (2017).

-

Schindelin, J. et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 676–682 (2012).

-

Pachitariu, M., Sridhar, S., Pennington, J. & Stringer, C. Spike sorting with Kilosort4. Nat. Methods 21, 914–921 (2024).

-

Siegle, J. H. et al. Open Ephys: an open-source, plugin-based platform for multichannel electrophysiology. J. Neural Eng. 14, 045003 (2017).

-

Pinto, L. et al. An accumulation-of-evidence task using visual pulses for mice navigating in virtual reality. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 12, 36 (2018).

-

Rodriguez, A. et al. ToxTrac: a fast and robust software for tracking organisms. Methods Ecol. Evol. 9, 460–464 (2018).

-

Wu, M. et al. Dopamine pathways mediating affective state transitions after sleep loss. Neuron 112, 141–154 (2024).

-

Wu, M. et al. Data and code for the article ‘Patterned wireless transcranial optogenetics generates artificial perception’. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14880024 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We thank L. Butler for mouse colony management and F. Valero-Cuevas for meaningful insights and discussions. This work made use of the NUFAB facility of Northwestern University’s NUANCE Center, which has received support from the SHyNE Resource (National Science Foundation (NSF) ECCS-2025633), the International Institute for Nanotechnology and Northwestern’s Materials Research Science and Engineering Center program (NSF DMR-2308691). MicroCT imaging work was performed at the Northwestern University Center for Advanced Molecular Imaging (RRID: SCR_021192), generously supported by National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA060553 awarded to the Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center. Microscopy analyses using Leica SP8 were performed at the Biological Imaging Facility at Northwestern University (RRID: SCR_017767), generously supported by the Chemistry for Life Processes Institute, the Northwestern University Office for Research, the Department of Molecular Biosciences and the Rice Foundation. This work was funded by the Querrey-Simpson Institute for Bioelectronics (M.W., Y.Y., A.I.E., A.V.-G., Y.W., J.G., L.Z., J.L., M.K., J.K., Y.H. and J.A.R.); National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS)/BRAIN Initiative 1U01NS131406 (Y.K. and J.A.R.); National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) R01MH117111 (Y.K.); NINDS R01NS107539 (Y.K.); 2021 One Mind Nick LeDeit Rising Star Research Award (Y.K.); Kavli Exploration Award (Y.K.); Shaw Family Pioneer Award; Center for Reproductive Science, Feinberg School of Medicine (J.M.C.); NIMH R00MH120047 (L.P.); Simons Foundation grant 872599SPI (L.P.); Alfred P. Sloan Foundation grant SP-2022-19027 (L.P.); North Carolina State University Start-up Fund 201473-02139 (A.V.-G.); 2T32MH067564 (J.Z.); and the Christina Enroth-Cugell and David Cugell fellowship (M.W.). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

J.A.R. and A.B. are co-founders in a company, Neurolux, Inc., that offers related technology products to the neuroscience community. C.H.G. is employed by Neurolux, Inc. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Neuroscience thanks Luis Carrillo-Reid and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

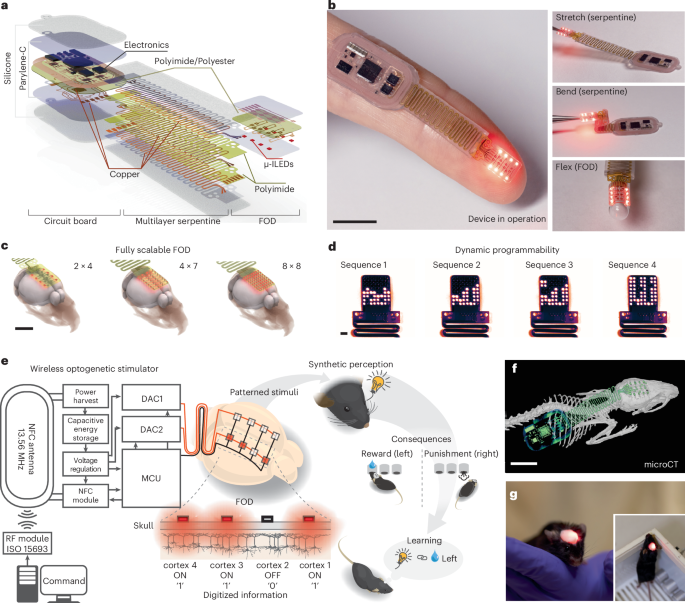

Extended Data Fig. 1 Device fabrication and assembly.

(a) Left, schematic illustration of the circuit base of the electronic module of the device using three-layer flexible printed circuit board (fPCB). Right, images of the fPCB for the electronic module. Scale bar: 5 mm. (b) Left, schematic illustration of the assembly of electronic components on the fPCB of the electronic module using hot-air soldering. Right, images of the electronic module after hot-air soldering of electronic components. (c) Left, schematic illustration of the circuit base of the FOD using three-layer fPCB. Right, magnified view of the soldering site for the μ-ILED with solder paste. Scale bar: 500 µm. (d) Left, schematic illustration of the FOD after hot-air soldering of the μ-ILEDs. Right, magnified view of the soldered μ-ILED. (e) Left, schematic illustration of the serpentine traces of the device using a five-layer fPCB. Right, image of the serpentine traces on the fPCB. Scale bar: 5 mm. (f) Left, image of the serpentine traces after laser ablation from the fPCB substrate. Right, scanning electron microscopic (SEM) image of the serpentine traces from lateral view. The experiment was repeated independently on 3 serpentine traces. Scale bar: 300 µm. (g) Schematic illustration of the final assembly of the electronic module, serpentine traces, and FOD. (h) Image of the final device after assembly. (i) Schematic illustration of the mold used for final silicone (Ecoflex 00-30) coating after parylene-C encapsulation. (j) Photograph of the device during mold casting of silicone. (k) Image of a fully encapsulated device ready for in vivo experiments.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Geometric optimization, numerical modeling, and experimental characterizations of serpentine interconnect.

(a) Left, geometric model of structures surrounding the serpentine interconnect. Right, calculation of the applied strain on the serpentine and equivalent strain on the Cu-based serpentine conductive traces. (b) Layered structure of the serpentine materials relative to the neutral mechanical plane. Left: 2-Cu-layer design; right: 3-Cu-layer design. (c) Equivalent strain distribution on copper traces with 13% applied strain. (d) When a certain strain is applied to the serpentine interconnect, a certain copper unit on the trace shows the highest equivalent strain among all units. Summary graph showing this highest equivalent strain versus applied strains. Equivalent strain for copper plastic deformation equals 0.3%. (e) Geometric parameters that affect the stretchability of the serpentine interconnects. (f) Serpentine design examples with different gap widths and radius. (g) Contour map summarizing the stretchability as a function of normalized gap width and radius. Stretchability: maximal applied strain without causing plastic deformation on copper-based conductive traces. (h) Average elongation of the gap when the serpentine interconnect is stretched. (i) Elongation of the gap results in principal strain on the elastomer, causing potential encapsulation defects. (j) Design 1 & 2: prototypes, not guided by numerical modeling; Design 3, optimized layer structure with preliminary modifications of gap width and connecting regions; Design 4, optimized layer structure and geometry guided by numerical modeling. (k) Equivalent strain on the Cu-based conductive traces versus applied strain on the serpentine interconnect for the four designs. Dashed line: Equivalent strain threshold for plastic deformation on the copper traces. (l) Finite element analysis (FEA) of equivalent strain on the optimized serpentine interconnect under stretching (left) and bending (middle). Right, the equivalent strain on the FOD when flexed to the curvature of the skull. Scale bar: 10 mm. (m) Schematic illustration of the benchtop validation of the modeling outcomes using cyclic stretching and bending tests of devices integrated on artificial skin immersed in saline. (n) Summary data showing normalized conductance loads on individual μ-ILEDs for 20k cycles in cyclic stretching and bending tests. n = 21 pairs of traces from 3 devices for design 1; n = 27 pairs of traces from 3 devices for design 2; n = 26 pairs of traces from 3 devices for design 3; n = 20 pairs of traces from 3 devices for design 4. Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. (o) Summary data for stable cycles where the devices maintain constant resistance during stretching and bending. n = 3 devices. Dots represent individual devices. (p) Images showing devices in operation in the Bpod chamber, 32 days after implantation.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Electronic modules for FOD with 2 × 4 configuration.

(a) Schematic illustrations showing electronic circuits for wireless power harvesting and voltage regulation. (b) Capacitor bank for energy storage and discharge. (c) Near-field communication module for real-time programming. (d) Micro-controller circuit for parameter (order, frequency, duty cycle) control. (e) Digital-to-analog converters for intensity modulation. (f) FOD. Essential components and input/output pins are labeled on the schematics.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Characterizations and validations for irradiance distribution profiles.

(a) Simulated magnetic-field-intensity distribution at the central plane of a behavioral cage (dimensions, 20 cm (length) × 14 cm (width)) with a double-loop antenna at heights of 3 cm and 6 cm. Scale bar: 10 cm. (b) Simulated magnetic-field-intensity distribution at different heights in the Bpod behavioral cage. (c) The total electrical power of the μ-ILED with respect to the primary antenna power. (d) The I-V characterization for the μ-ILED. (e) The optical power of the μ-ILED with respect to the input current. (f) Schematic illustration (left) and image (right) of the experimental setup for measuring light attenuation through the skull and brain tissue. (g) Simulated (left) and measured (right) results of light attenuation through the skull. A 60 µm layer of skull was used in the numerical model. A piece of thinned skull was used for measurement. (h) Illumination volume and penetration depth as a function of the input irradiance of the red μ-ILED (628 nm). Threshold intensity, 1 mW/mm2. (i) Contour map plot showing total overlap volume from 4 μ-ILED co-activation for different input optical power and intensity thresholds for opsin variants.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Numerical and experimental assessments of heat accumulation to guide stimulation parameters.

(a) Left, image of micro-fabricated thermistor for measuring temperature; middle, schematic illustration of the experimental setup for measuring heat accumulation in the structures surrounding the optical-neural interface; right, image of experimental setup, with wires connected to the thermistors to collect resistance value. Scale bar: 500 µm. (b) Calibration curves of thermistors used in this study for measuring the temperature increase on the surface of skull (left), on the surface of brain (middle), and below the µ-ILED (right). Each dot represents one resistance measurement at one temperature measurement. The best-fit line represents the linear regression between resistance and temperature. n = 1 representative thermistor at each location (skull, brain, or µ-ILED). (c) Simulated (Top) and measured (bottom) results of temperature increase below the µ-ILED for 3 s μ-ILED operation. The temperature increases in a 20 × 300 × 300 µm3 volume, 100 µm below the μ-ILED surface, was output from the numerical model. The thermistor was manually placed and adhered to the μ-ILED surface, followed by a complete procedure of μ-ILED array fabrication. Measured data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. n = 3 technical replicates. Technical replicates are included to account for fluctuations in environmental temperature. (d) Left, simulated maximal temperature increases on the skull surface during μ-ILED operation with 10% duty cycle at varying frequencies. Right, same as left, but for varying duty cycles at 10 Hz. The finite element node with maximal temperature increase (max. node) was selected for plotting. (e) Same as (d), but for brain surface. (f) Left, measured temperature increases on the skull surface during μ-ILED operation with 10% duty cycle at varying frequencies. Right, same as left, but for varying duty cycles at 10 Hz. (g) Same as (f), but for brain surface. (h) Heatmap showing simulated heat production during a single μ-ILED operation in air at 100% duty cycle and 1.93 mW power for 10 s. Left, fPCB array patch without modification. Right, fPCB array patch coated with 100 µm Cu on the rear side. (i) Simulated temperature increases with or without device surface modification with 100 µm Cu.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Opsin expression and surgical procedures.

(a) Representative images of ChrimsonR expression in the targeted cortical regions from one mouse. The experiment was repeated independently on 8 animals. (b) Heatmap showing the spread of viral expression across cortical regions. n = 8 animals. (c) Example image showing the distribution of tdT, vglut1, and vgat transcripts in cortical column of somatosensory cortex limb representation. L1, 1 to 100 μm, L2/3, 100 to 300 μm, L4, 300 to 400 μm, L5a, 400 to 500 μm, L5b, 500 to 700 μm, L6a, 700 to 900 μm. Scale bar, 25 μm. The experiment was repeated independently on 16 brain slices from 4 animals. (d) Schematic illustration of critical steps of surgical implantation.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Extracellular recording in ChrimsonR-negative mice and evoked local field potentials (LFPs) in ChrimsonR-positive mice.

(a) Schematic of in vivo extracellular electrophysiology recordings in ChrimsonR-negative mice. (b) Left, raw recording traces showing the electrical artifacts during the stimulation period at different distances (1,000-5,000 μm) from μ-ILED. Right, processed traces using a custom-modified version of the Estimation and Removal of Array Artifacts via Sequential Principal Components Regression (ERAASR) algorithm. Lines and shaded areas represent mean ± s.e.m. (c) Schematic of the in vivo extracellular electrophysiology recording setup for evoked LFPs in ChrimsonR positive mice. (d) Traces showing evoked LFPs averaged across all electrodes of the MEA at different distances from the μ-ILED with varying input optical power. Lines and shaded areas represent mean ± s.e.m. (e) Summary of evoked LFP magnitudes at different distances from the μ-ILED under varying input optical power levels. Lines represent the mean from all electrodes, and dots indicate individual electrode measurements. (f) Same as (e), but for latency to valley in LFP waveforms. Dots represent individual electrodes; lines indicate the mean.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Operant learning performance, reaction time analysis, and open-field locomotion analysis.

(a) Number of sessions of 100 trials each across three levels of the task to reach the criterion of 80% success rate for animals expressing ChrimsonR (session median Level 1-12, Level 2-6, Level 3-12). One-way ANOVA, p = 0.5750, F (2, 28) = 0.5645; Sidak’s multiple comparisons test, Level 1 vs Level 2, p = 0.7258; Level 2 vs Level 3, p = 0.7596; Level 1 vs Level 3, p > 0.9999; Level 1, n = 11 animals; Level 2, n = 10 animals; Level 3, n = 10 animals. Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. Dots represent individual animals. (b) Summary data showing the total training length to complete Levels 1-3 and the number of sessions per day. Dark orange, group average; pale orange, individual trajectories; symbols mark the day individual animals reached criterion. (c) Timeline from water restriction to the end of training. Open-field locomotion was measured at the start of water restriction, before device implantation, and 2, 5, and 10 days post-implantation. (d) Left, average movement speed in an open-field arena across days, one-way ANOVA, F (1.739, 5.217) = 1.632, p = 0.2773. Middle, same as left, but for acceleration, one-way ANOVA, F (2.154, 6.461) = 2.358, p = 0.1693. Right, same as left, but for exploration rate, one-way ANOVA, F (1.497, 4.491) = 3.271, p = 0.1354. Box plots show median (line), 25th and 75th percentiles (bounds of box), minimum and maximum values (whiskers). n = 4 animals. (e) Scatter plots showing reaction times in all trials for the Level 3 task as a function of total cortical distance between stimulated digits. (f) Summary data of cumulative distributions of reaction times for all animals.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Spatiotemporal analysis of behavioral trajectories for individual animals.

(a) Line plots showing success rate as a function of spatial distance for 10 individual animals in the Level 3 task. The number of trials with correct or incorrect choices in each bin of spatial distance is plotted in the histogram. (b) Heatmap showing success rate for randomized non-target sequences grouped by specific stimulation locations at the first to the fourth stimulation digit in 10 ChrimsonR expressing animals. Red squares indicate the target stimulation sequence for each animal. (c) Two-sided Pearson’s correlation analysis of spatial distance and success rate based on stimulation digit for individual animals. Dashed lines indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Extended Data Fig. 10 Cue-discrimination of varying spatiotemporal patterns.

(a) Left, schematic illustration of probing sequences with 75% (3 stimulation digits) and 50% similarity (2 stimulation digits) to the target sequences. Right, summary data showing the success rate of all probing sessions from all animals. 75% overlap, 0.6077 ± 0.0146; 50% overlap, 0.7312 ± 0.0203; Two-sided unpaired t-test, p < 0.0001. 75% overlap: n = 75 sessions from 5 animals; 50% overlap: n = 41 sessions from 5 animals. (b) Left, schematic illustration of probing experiments with reversed sequences. Right, summary data showing success rate of all probing sessions from all animals, 0.7347 ± 0.00338; One sample t-test vs 0.5, p < 0.0001; n = 15 sessions from 5 animals. (c) Schematic illustrating single site stimulation task for mice to discriminate neighboring stimulation either on the same hemisphere or on the contralateral hemisphere. (d) Left, example of target (stimulation on a single cortical region) and non-target stimulation on a neighboring site. Middle, summary data showing discrimination performance on neighboring stimulation sites. Ipsilateral, 0.6151 ± 0.0168; one sample t-test vs 0.5, p < 0.0001; n = 58 sessions from 5 animals. Contralateral, 0.7081 ± 0.0257; one sample t-test vs 0.5, p < 0.0001; n = 20 sessions from 3 animals; Two-sided unpaired t-test, ipsi vs contra, p = 0.0053. Right, summary data showing discrimination of ipsilateral neighboring stimulation, 1st column (motor vs limb), 0.6788 ± 0.0542; one sample t-test vs 0.5, p = 0.0132. 2nd column (limb vs trunk), 0.6147 ± 0.0471; one sample t-test vs 0.5, p = 0.0288. 3rd column (trunk vs visual), 0.6007 ± 0.0149; one sample t-test vs 0.5, p < 0.0001. One-way ANOVA, Sidak’s multiple comparisons test, 1st vs 2nd column, p = 0.5884; 1st vs 3rd column, p = 0.3287; 2nd vs 3rd column, p = 0.9792. (e) Left, example of a target and a non-target stimulation, where one digit was switched to a neighboring site. Middle, summary data showing no significant difference in discrimination performance when the switched neighboring digit was in the ipsilateral or contralateral hemisphere. Ipsilateral, 0.6132 ± 0.0239; one sample t-test vs 0.5, p < 0.0001; n = 24 sessions from 3 animals. Contralateral, 0.5935 ± 0.0249; one sample t-test vs 0.5, p = 0.0013; n = 20 sessions from 3 animals; Two-sided unpaired t-test, ipsi vs contra, p = 0.5742. Right, summary data showing discrimination performance when the switched digit was in the ipsilateral hemisphere, 1st column (motor vs limb), 0.5930 ± 0.0462; one sample t-test vs 0.5, p = 0.0786. 2nd column (limb vs trunk), 0.6600 ± 0.0620; one sample t-test vs 0.5, p = 0.0494. 3rd column (trunk vs visual), 0.6022 ± 0.0196; one sample t-test vs 0.5, p = 0.0008. One-way ANOVA, Sidak’s multiple comparisons test, 1st vs 2nd column, p = 0.6523; 1st vs 3rd column, p = 0.9978; 2nd vs 3rd column, p = 0.7640. (f) Left, example of a target stimulation for mice to discriminate the target against each individual digit within it. Right, summary data of performance, 1st stim. (target vs 1st digit of the target), 0.6893 ± 0.0196; one sample t-test vs 0.5, p < 0.0001. 2nd stim., 0.7911 ± 0.0703; one sample t-test vs 0.5, p = 0.0033. 3rd stim., 0.7600 ± 0.0428; one sample t-test vs 0.5, p = 0.0017. 4th stim., 0.9020 ± 0.0132; one sample t-test vs 0.5, p < 0.0001. One-way ANOVA, Sidak’s multiple comparisons test, 1st vs 2nd stim., p = 0.3006; 1st vs 3rd stim., p = 0.8439; 1st vs 4th stim., p = 0.0164; 2nd vs 3rd stim., p = 0.9991; 2nd vs 4th stim., p = 0.6932; 3rd vs 4th stim., p = 0.5151. (g) Left, example of a target for mice to discriminate the target against its first digit, with the initiation site across all cortical regions. Right, summary data of performance, motor (target initiates from the motor cortex), 0.7000 ± 0.0397; one sample t-test vs 0.5, p = 0.0005. somalimb, 0.6355 ± 0.0539; one sample t-test vs 0.5, p = 0.0031. somatrunk, 0.6625 ± 0.0309; one sample t-test vs 0.5, p < 0.0001. visual, 0.7497 ± 0.0339; one sample t-test vs 0.5, p < 0.0001. One-way ANOVA, Sidak’s multiple comparisons test, motor vs somalimb, p = 0.8672; motor vs somatrunk, p = 0.9840; motor vs visual, p = 0.9414; somalimb vs somatrunk, p = 0.9972; somalimb vs visual, p = 0.2442; somatrunk vs visual, p = 0.4324. (h) Left, example showing mice discriminate stimulations on the same site with different durations. Right, summary data of performance. 0.3 s (1.2 s target vs 0.3 s like-target), 0.7256 ± 0.0384; one sample t-test vs 0.5, p = 0.0004. 0.6 s, 0.7088 ± 0.0396; one sample t-test vs 0.5, p = 0.0012. 0.9 s, 0.6087 ± 0.0642; one sample t-test vs 0.5, p < 0.0001. One-way ANOVA, Sidak’s multiple comparisons test, 0.3 s vs 0.6 s, p = 0.9503; 0.3 s vs 0.9 s, p = 0.0003; 0.6 s vs 0.9 s, p = 0.0031. All data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. Dots represent individual sessions of 100 trials. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 for two-sided t-test and multiple comparisons. #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001, ####p < 0.0001 for one-sample t-test vs 0.5.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, M., Yang, Y., Zhang, J. et al. Patterned wireless transcranial optogenetics generates artificial perception. Nat Neurosci (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-025-02127-6

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

Version of record:

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-025-02127-6