Introduction

From unicellular organisms to complex multicellular systems like humans, bridging the gap between cellular-level and organism-level biology remains a fundamental challenge. Organoids, or “mini-organs,” recapitulate the structure and physiological functions of their corresponding organs1,2,3. As physiologically rich in vitro models, they self-assemble from embryoids into mature organoids, offering a potential bridge between traditional cell cultures and animal models4. Organoids represent higher-dimensional systems than single cells, providing superior in vitro platforms for systematic life science research5. Despite this promise, technological barriers persist in applications such as three-dimensional (3D) bioprinting6,7,8, complex organoid construction9,10,11, and organ-on-a-chip fabrication12,13,14.

Organoid development is broadly categorized into two spatial patterns: two-dimensional (2D) and 3D cultures15,16,17. These two patterns determine different application scenarios: 2D cultures are currently widely used for constructing organ-on-a-chip devices18,19. Usually, two types of monolayer organoids or endothelial cell-organoid monolayers are constructed to explore the interaction between vascular barriers and tissues and the interaction between organs20,21. Three-dimensional cultures create an organoid niche more similar to the organoid’s actual environment, thus simulating a more realistic in vitro tissue microenvironment22,23. Based on their structural differences, potential technical challenges still remain, such as fluorescence labeling and high-quality 3D visualization. Two-dimensional organoids can be easily labeled in the same manner as traditional cell lines, as their excellent adhesion prevents the monolayer organoids from releasing from the plate during repeated and direct contact with the liquid during the labeling process24 when using labeling conditions similar to those of cell lines. For 3D organoids, conditions must be changed due to the Matrigel dome-enveloped structure25. Among these structures, liquid stains generally have difficulty permeating the Matrigel and achieving contact with the organoids. Hence, in 3D organoid labeling, removing the Matrigel is necessary. However, a novel problem presents itself. Matrigel-removed 3D organoids cannot be fixed in liquid like their 2D counterparts while transferring the liquid. Limited strategies have been attempted to solve this problem, but with little success. In each labeling step, existing methods often cause the organoids to sink due to gravity settling or repeated centrifugation26,27. Obvious drawbacks to these methods include the direct physical impact of the liquid and repeated centrifugal forces that disrupt the organoid structure. By accident, we found that a cell strainer functioned to stabilize intestinal organoids (IOs) in liquid, due to the nylon mesh of the strainer28,29.

Here, we designed the nylon mesh chip to promote the stability of IOs in liquid based on embedding them in a nylon mesh, thereby supporting the development of an improved IO labeling methodology. Moreover, the chip was designed to be adapted to laser confocal microscopy. In summary, this invention promotes high-quality 3D visualization of IOs. Given these distinctive characteristics, the nylon mesh chip holds promise of being further developed and adapted to a broader range of budding organoids30,31. This advancement is anticipated to achieve high-quality 3D visualization across multiple organoid types.

Results and discussion

Structural characterization of the nylon mesh chip

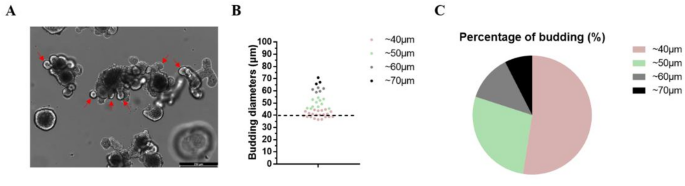

The nylon mesh chip was designed based on a serendipitous discovery: intestinal organoids (IOs) could be embedded within the nylon mesh of a cell strainer28, enabling retention of numerous IOs at a 40-µm pore size. We measured the diameters of 40 IO budding structures (Fig. 1A and B; red arrows indicate IO buddings; colored dots denote diameters: red = 40 μm, green = 50 μm, gray = 60 μm, black = 70 μm). Over 50% of buddings exhibited diameters ≈ 40 μm (Fig. 1C). This finding motivated the use of nylon mesh as a liquid-phase support for IOs, enhancing labeling efficiency.

As shown in Fig. 2A, the chip features upper, middle, and lower layers. The core is a nylon mesh (middle layer) that spatially stabilizes IOs in liquid. Designed with an 18-mm diameter, the chip fits standard 21-mm 12-well plates or 20-mm glass-bottom confocal dishes, allowing immunofluorescence assays (IFA) in both systems. Here, 12-well plates were used due to their smaller well area. The design is scalable to 24-, 48-, or 96-well plates32,33,34 based on demand. To ensure compatibility with laser confocal microscopy, the upper glass thickness was set to 0.2 mm (preserving z-axis depth), while the lower glass was 2 mm thick (Fig. 2B). Based on the design depth of the nylon mesh chip and the limitations of mesh pore size, organoids with a thickness of more than 40 μm and less than 200 μm may be more suitable. It is worth noting that organoids with a thickness exceeding 200 μm can also be considered, provided that the deformation of organoids caused by slight extrusion is acceptable. For IFA in 12-well plates, 500 µL liquid sufficed to submerge the chip (well diameter: 21 mm). A notch in the lower layer facilitated liquid flow during upright labeling (Fig. 2C–E).

Statistics of budding quantity. (A) Bright-field images of IO. The red arrows indicate IO buddings (scale bar = 250 μm). (B) Diameters from 40 IO budding structures. The dots in colors of red, green, gray, and black respectively indicate buddings with diameters of approximately 40, 50, 60, and 70 μm. (C) Percentage of buddings with different sizes.

Structure of the nylon mesh chip for IO labeling. (A) The device is composed of three layers and displayed here in a 2D top view. The upper layer is a complete circular glass structure (inner diameter = 10 mm, outer diameter = 18 mm). The middle layer is a nylon mesh with a mesh size of about 40 μm (diameter = 18 mm). The lower layer is the same material as the upper layer but with a notch (inner diameter = 10 mm, outer diameter = 18 mm, and length of notch = 4 mm). (B) The 2D front view of the nylon mesh chip (upper glass thickness = 0.2 mm, lower glass thickness = 2 mm). (C) Upright view of the nylon mesh chip on its edge (scale bar = 4 mm). (D) Upper view of the nylon mesh chip (scale bar = 4 mm). (E) Inverted view of the nylon mesh chip (scale bar = 4 mm).

The nylon mesh was clamped between glass layers and bonded with UV-cured adhesive. Glass was chosen over low-density plastics (e.g., polyethylene) to prevent chip flotation35. Curing under 365–400 nm UV light (10–30 s) yielded the final device (Fig. 3).

Assembly of the nylon mesh chip. The components of the device were assembled by stacking and layers were adhered using a UV-cured adhesive.

IO labeling process based on the nylon mesh chip

The IO labeling protocol mainly comprised the following six steps: expansion of the organoid, Matrigel removal, organoid loading (Fig. 5D), IFA labeling, chip inversion, and microscopic imaging (Fig. 4). The IOs must be resuspended in ice-cold PBS and centrifuged at 290 × g and 4 °C for 5 min to eliminate any remaining Matrigel prior to labeling (Fig. 4, step 2). This prevents interference from Matrigel components that reduce fluorescence quality. The IFA labeling process was carried out in a 12-well plate containing the nylon mesh chips. During labeling, the chip was placed upright in the well (Fig. 5A). Critically, adding or removing liquid must be performed slowly along the side wall or bottom of the well to avoid damaging the organoid structure with excessive liquid shear stress (Fig. 4, step 4; Fig. 5E and F). For imaging, the chip was inverted and placed in a 12-well plate or confocal dish (Fig. 5B and C). Subsequently, IO samples were observed and images acquired under a fluorescence microscope or laser confocal microscope.

Complete IO immunofluorescence labeling process based on the nylon mesh chip. The procedure includes the following steps: IO expansion, Matrigel removal, IO loading, IFA labeling, chip inversion, and organoid 3D reconstruction and imaging.

Demonstration and operational details of the nylon mesh chip in a well. (A and B) Top views of the upper and inverted nylon mesh chip in a 12-well plate (scale bar = 4 mm). (C) Top view of the inverted chip in a confocal dish with a glass bottom (scale bar = 4 mm). (D–F) Demonstration of sample loading, liquid addition, and liquid removal in a 12-well plate (scale bar = 4 mm).

Nylon mesh chip provides IO visualization

To explore interface interactions between IOs and the nylon mesh chip, fluorescence images of villin-labeled IOs were collected. Before inversion, bright-field imaging showed IOs partially or completely obscured by the nylon mesh (Fig. 6A; red arrows indicate nylon mesh). After inversion, DAPI-labeled IOs were visualized. Despite clear images, the nylon mesh absorbed DAPI (Fig. 6B; red arrows indicate labeled mesh), hindering fluorescence analysis. When observing Alexa Fluor 488-coupled villin, IOs were shaded by the mesh both pre- and post-inversion (Fig. 7A and B; red arrows: fluorescent mesh; white arrows: interference). We compared IO retention between 40 μm and 70 μm meshes after inversion. The 40 μm mesh retained significantly more samples (Fig. 8A-C), confirming its suitability. Conventional fluorescence imaging failed to fully meet IO imaging requirements due to mesh interference. However, the chip remains applicable for detecting viral infections or target protein29. For high-quality imaging, laser confocal 3D reconstruction was employed. Z-stack scanning from the IO base to the chip surface produced high-resolution 3D images showing IO-mesh interactions (Fig. 9A; Video S1). By scanning only IO layers beneath the chip, unobstructed 3D reconstructions were achieved (Fig. 9B; Video S2). This minimized redundant signals since the mesh layer was excluded. Figure 10A shows buddings embedded in the mesh (red arrows), providing liquid stability. Figure 10B illustrates the workflow: embedding, inversion, and Z-stack scanning.

Microscopic observation of the interface between IOs and the nylon mesh. (A) Bright field imaging of IOs in a 12-well plate before inverting the chip. Red arrows indicate nylon grid lines (scale bar = 50 μm). (B) Fluorescent imaging of IOs in a 12-well plate after inverting the chip (scale bar = 500 μm). Red arrows indicate nylon grid lines (scale bar = 100 μm). Cell nuclei are stained with blue fluorescence by using DAPI dye.

Fluorescence imaging of IOs under a fluorescence microscope. (A) Fluorescent imaging of IOs in a 12-well plate before inverting the chip (scale bar = 50 μm). (B) Fluorescent imaging of IOs in a 12-well plate after inverting the chip (scale bar = 50 μm). Villin protein was labeled with green fluorescence, and red arrows indicate nylon grid lines. White arrows indicate the fluorescent shadow of the nylon grid lines through the contact interface between the IOs and nylon mesh.

40 μm nylon mesh chip retains more IO samples. (A) The distribution of IOs on the 40 μm nylon mesh chip. Red arrows indicate IOs (scale bar = 500 μm). (B) The distribution of IOs on the 70 μm nylon mesh chip. Red arrows indicate IOs (scale bar = 500 μm). (C) The remaining number of IOs after inverting 40 μm and 70 μm nylon mesh chips. Black and red dots respectively indicate IOs from 40 μm and 70 μm nylon mesh chips.

The 3D reconstruction and high-quality visualization of IOs based on the nylon mesh chip. (A) IO 3D imaging showing the contact interface in a confocal dish after inverting the chip (scale bar = 100 μm). (B) IO 3D reconstruction and visualization without the contact interface in the confocal dish (scale bar = 100 μm). The Villin protein was labeled with green fluorescence.

The detail of interface interaction between IO and nylon mesh. (A) IO 3D imaging displays the interface interaction. Red arrows indicate IO buddings are embedding into nylon mesh and relevant detail images are displayed in the upper left-hand and upper right-hand corners. (scale bar = 50 μm). (B) The cartoon illustration shows the schematic of IO being embedded in the mesh and inverted. Subsequently, IO is scanned via Z-stack.

Finally, we compared three labeling methods:

Chip-based labeling: Preserved structure with clear imaging (Fig. 11A); Matrigel-embedding: Reduced signal-to-noise ratio (Fig. 11B and E); Free-floating in dish: Structural damage despite high signal-to-noise (Fig. 11C and E). The mesh exhibited autofluorescence with Alexa Fluor 594/647 (Fig. 11D). It is worth noting that for this nylon mesh chip, the liquid may need to be added more slowly to prevent the IO from detaching from the embedded chip. A vertical cylindrical plastic structure may be considered for placement in the center of the chip, preventing IOs that detach from the chip from floating directly in the liquid. However, the anti-adhesion ability of this new structure still needs to be considered to prevent the IO from adhering to the wall of the cylinder. In conclusion, the nylon mesh chip demonstrated significant potential for visualizing IOs. Given the critical importance of high-throughput detection of organoids in new drug development36,37,38, this chip is anticipated to evolve into a robust tool that integrates with multi-well glass bottom culture plates and automatic microfluidic devices, thereby facilitating high-throughput screening.

The detail of interface interaction between IO and nylon mesh. (A) IO is labeled by using nylon mesh chip and 3D imaging is presented (scale bar = 50 μm). (B) IO in Matrigel is directly labeled and a 3D image was obtained (scale bar = 50 μm). (C) The free-floating IO in the dish is directly marked and a 3D image is obtained (scale bar = 50 μm). (D) Nylon mesh chip carries autofluorescence (scale bar = 50 μm). (E) Signal-to-noise ratio of these three labeling methods.

In conclusion, while the nylon mesh chip labeling method enhances 3D visualization of IOs by offering a better signal-to-noise ratio than direct labeling in Matrigel and reducing structural damage compared to free-floating IOs, it faces limitations. This chip was validated only for imaging, and its impact on organoid biology (viability, function, differentiation) remains unknown. Furthermore, the autofluorescence of the nylon mesh necessitates alternative materials to minimize noise and enable deeper Z-stack scanning. Future expansion of the materials used in the nylon mesh chip is expected to significantly increase its usefulness for high-throughput imaging and basic research.

Materials and methods

Animal

A six-week-old male C57BL/6 mouse weighing approximately 20 g was utilized in this study (SPF Biotechnology, Beijing, China). All animal experiments described above were approved by the Guidelines of the Institute of Traditional Chinese Medicine Health Industry (China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences) for Institutional Animal Care. All the experimental procedures were performed in accordance with the Good Animal Practice Requirements of the Animal Ethics Procedures and Guidelines of the People’s Republic of China. This study was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the Institute of Traditional Chinese Medicine Health Industry, China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences [approval number: 2024014], and all animal tests were conducted in strict accordance with animal welfare guidelines. The study is reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines.

Device fabrication

A nylon mesh chip, constructed with a thin upper glass, nylon mesh (NY4102500, Millipore, USA), and a thick lower glass, was sized to fit into a 12-well plate (150628, Thermo, USA) for embedding and labeling IOs. The thick glass was produced by cutting, edging, and cleaning, while the thin glass was made by float drawing. The chip was assembled using medical-grade UV-curable adhesive (AA3311, LAOGUKE, China) and cured under 365–400 nm UV light. Adhesive was added layer by layer in a bottom-to-top order: Adhesive was added dropwise to the upper edge of the thick glass. Then, the nylon mesh was superimposed on the glass, and more adhesive was added dropwise. Finally, the thin glass was place on top of the adhesive). Adhesive was added using a Finnpipette F3 micropipette (4640050, Thermo, USA).

Crypt isolation and IO culture

A C57BL/6 mouse was used to isolate intestinal crypts. Following anesthesia with 3% isoflurane, the mouse was euthanized by cervical dislocation, and its intestinal tissue was collected. The intestine underwent mucosal removal and was washed several times with phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Next, the intestine was cut into fragments that were isolated with a gentle cell dissociation reagent (07174, STEMCELL Technologies, Canada) to obtain crypts. The collected crypts were counted and plated onto Matrigel® matrix domes (356231, Corning, USA) according to the specified concentration. Subsequently, IntestiCult™ organoid growth medium (mouse) (06005, STEMCELL Technologies, Canada) was supplemented in the wells. The medium was changed every three days. The IO development status was monitored daily.

IO labeling on the nylon mesh chip, in matrigel or in the liquid

First, IOs were resuspended in ice-cold PBS and centrifuged at 290 × g and 4 °C for 5 min to remove the Matrigel. Subsequently, IO samples were transferred onto the nylon mesh chip for fluorescent labeling. An indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA) was performed on the IOs according to a general labeling procedure. This included the following steps: IOs were fixed for 30 min in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA, G1101, Servicebio, China), then permeabilized for 5 min in 0.1% Triton X-100 (93443, Sigma, USA), blocked for 30 min in 10% goat serum (SL038, Solarbio, China), incubated in the primary antibody (villin, ab97512, Abcam, USA; β-catenin, sc-7963, Santa Cruz, USA; Claudin-1, ab129119, Abcam, USA) overnight, incubated in the secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor™ Plus 488, A32731, Thermo, USA; Alexa Fluor® 594, ab150116, Abcam, USA; Alexa Fluor® 647, ab150083, Abcam, USA) for 60 min, and stained with DAPI for 5 min to visualize the nuclei (C0065, Solarbio, China). The IOs were observed and imaged under an inverted fluorescence microscope (DMI8, Leica, Germany) or a laser confocal system (AXR, Nikon, Japan). IOs embedded in Matrigel and floating in the liquid were directly labeled via 4% PFA fixation, permeation, blockage, primary antibody incubation and secondary antibody incubation.

Three-dimensional reconstruction and imaging of IOs at the nylon mesh chip interface

Fluorescently labeled IOs were then used for 3D reconstruction. After IFA labeling was completed according to the indicated protocol, the nylon mesh chip was inverted and transferred into a new glass bottom confocal dish (801001, NEST, China) containing PBS. The 0.2-mm thin glass of the chip provided a sufficient working distance for the laser confocal device. The fluorescence images of IOs were scanned layer by layer at a 1-µm interval. Subsequently, the images were superimposed using the reconstruction capabilities of the laser confocal system, thereby achieving high-quality 3D visualization of the IOs. IOs embedded in Matrigel and floating in the liquid have also been reconstructed through Z-stack scanning.

Statistical analysis

Data were presented as mean and standard deviation (SD). The t-test was performed for the statistical analysis using GraphPad Prism software 6.01, and the p values represent significant differences (***, p < 0.001).

Data availability

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

References

-

Sato, T. et al. Single Lgr5 stem cells build crypt-villus structures in vitro without a mesenchymal niche. Nature 459, 262–265 (2009).

-

T Neal, J. et al. Organoid modeling of the tumor immune microenvironment. Cell 175, 1972–1988 (2018). .

-

Schafer, S. T. et al. An in vivo neuroimmune organoid model to study human microglia phenotypes. Cell 186, 2111–2126e2120 (2023).

-

Ryu, S. et al. Stress-free cell aggregation by using the CEPT cocktail enhances embryoid body and organoid fitness. Biofabrication 16, 1452 (2023).

-

Tang, C., Wang, X., D’Urso, M., van der Putten, C. & Kurniawan, N. A. 3D interfacial and Spatiotemporal regulation of human neuroepithelial organoids. Adv. Sci. (Weinheim Baden-Wurttemberg Germany). 9, e2201106 (2022).

-

Maharjan, S. et al. Advanced 3D imaging and organoid Bioprinting for biomedical research and therapeutic applications. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 208, 115237 (2024).

-

Lawlor, K. T. et al. Cellular extrusion Bioprinting improves kidney organoid reproducibility and conformation. Nat. Mater. 20, 260–271 (2021).

-

Zhang, Y. S. et al. Bioprinting 3D microfibrous scaffolds for engineering endothelialized myocardium and heart-on-a-chip. Biomaterials 110, 45–59 (2016).

-

Chen, S., Chen, X., Geng, Z. & Su, J. The horizon of bone organoid: a perspective on construction and application. Bioactive Mater. 18, 15–25 (2022).

-

Peng, K. et al. HIF-1α promotes kidney organoid vascularization and applications in disease modeling. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 14, 336 (2023).

-

Kroll, K. T. et al. Immune-infiltrated kidney organoid-on-chip model for assessing T cell bispecific antibodies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 120, e2305322120 (2023).

-

Shirure, V. S., Hughes, C. C. W. & George, S. C. Engineering vascularized organoid-on-a-chip models. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 23, 141–167 (2021).

-

Liu, S. et al. Biosensors integrated 3D organoid/organ-on-a-chip system: a real-time biomechanical, biophysical, and biochemical monitoring and characterization. Biosens. Bioelectron. 231, 115285 (2023).

-

Quintard, C. et al. A microfluidic platform integrating functional vascularized organoids-on-chip. Nat. Commun. 15, 1452 (2024).

-

Zeldich, E. & Rajkumar, S. Identity and maturity of iPSC-Derived oligodendrocytes in 2D and organoid systems. Cells 13, 4523 (2024).

-

Brooks, A. et al. Liver organoid as a 3D in vitro model for drug validation and toxicity assessment. Pharmacol. Res. 169, 105608 (2021).

-

Ishiguro, Y. et al. Lineage tracing of T cell differentiation from T-iPSC by 2D feeder-free culture and 3D organoid culture. Front. Immunol. 14, 1303713 (2023).

-

Sun, W. et al. Organ-on-a-Chip for Cancer and immune organs modeling. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 8, e1801363 (2019).

-

Wu, H. et al. Recent progress of organ-on-a-chip towards cardiovascular diseases: advanced design, fabrication, and applications. Biofabrication 15, 4123 (2023).

-

Skardal, A. et al. Drug compound screening in single and integrated multi-organoid body-on-a-chip systems. Biofabrication 12, 025017 (2020).

-

Maulana, T. I. et al. Breast cancer-on-chip for patient-specific efficacy and safety testing of CAR-T cells. Cell. Stem Cell. 31, 989–1002e1009 (2024).

-

Rauth, S., Karmakar, S., Batra, S. K. & Ponnusamy, M. P. Recent advances in organoid development and applications in disease modeling. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta Rev. cancer. 1875, 188527 (2021).

-

Yi, S. A., Zhang, Y., Rathnam, C., Pongkulapa, T. & Lee, K. B. Bioengineering approaches for the advanced organoid research. Adv. Mater. (Deerfield Beach Fla). 33, e2007949 (2021).

-

Ettayebi, K. et al. Replication of human Noroviruses in stem cell-derived human enteroids. Sci. (New York N Y). 353, 1387–1393 (2016).

-

Kim, S. et al. Tissue extracellular matrix hydrogels as alternatives to matrigel for culturing Gastrointestinal organoids. Nat. Commun. 13, 1692 (2022).

-

Dekkers, J. F. et al. High-resolution 3D imaging of fixed and cleared organoids. Nat. Protoc. 14, 1756–1771 (2019).

-

Zhang, M. et al. Long-Term expansion of Porcine intestinal organoids serves as an in vitro model for swine enteric coronavirus infection. Front. Microbiol. 13, 865336 (2022).

-

Tan, J. et al. A Strainer-Based platform for the collection and Immunolabeling of mouse intestinal organoids. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 412 (2023).

-

Liu, Y., Tan, J., Zhang, N., Li, W. & Fu, B. A strainer-based platform for the collection and Immunolabeling of Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus-infected Porcine intestinal organoid. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24,412 (2023).

-

Miller, A. J. et al. Generation of lung organoids from human pluripotent stem cells in vitro. Nat. Protoc. 14, 518–540 (2019).

-

Randriamanantsoa, S. J., Raich, M. K., Saur, D., Reichert, M. & Bausch, A. R. Coexisting mechanisms of luminogenesis in pancreatic cancer-derived organoids. iScience 27, 110299 (2024).

-

Xie, B. Y. & Wu, A. W. Organoid culture of isolated cells from patient-derived tissues with colorectal cancer. Chin. Med. J. 129, 2469–2475 (2016).

-

Shrestha, S. et al. Reproducible generation of human liver organoids (HLOs) on a pillar plate platform via microarray 3D Bioprinting. Lab. Chip. 24, 2747–2761 (2024).

-

Choi, H. K. et al. Regenerative capacity of alveolar type 2 cells is proportionally reduced following disease progression in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis-derived organoid cultures. Tuberculosis Respir. Dis. (2024).

-

Meng, J., Zhang, Q., Ma, M., Shi, H. & He, G. Persistence of avian influenza virus (H9N2) on plastic surface. Sci. Total Environ. 834, 155355 (2022).

-

Luo, Z. et al. Establishment of a large-scale patient-derived high-risk colorectal adenoma organoid biobank for high-throughput and high-content drug screening. BMC Med. 21, 336 (2023).

-

Geyer, M. & Queiroz, K. Microfluidic platforms for high-throughput pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma organoid culture and drug screening. Front. Cell. Dev. Biology. 9, 761807 (2021).

-

Norkin, M., Ordóñez-Morán, P. & Huelsken, J. High-content, targeted RNA-seq screening in organoids for drug discovery in colorectal cancer. Cell. Rep. 35, 109026 (2021).

Acknowledgements

Thanks for the support of the research platform of Institute of Traditional Chinese Medicine Health Industry and the project sponsor.

Funding

This work was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Public Welfare Research Institutes (grant number: ZZ18-ND-12, ZZ18-XRZ-090) and Scientific Research Foundation for the Introduction of Talent (grant number: QD-2024005B).

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tan, J., Li, Y., Wang, M. et al. Nylon mesh chip promotes three-dimensional visualization of intestinal organoids. Sci Rep 15, 26118 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12015-5

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12015-5