Introduction

Mpox virus (MPXV), formerly monkeypox virus, is a zoonotic virus classified in the Orthopoxvirus genus of the Poxviridae family that causes smallpox-like symptoms in humans1,2,3. This virus was endemic in Central and West Africa, however, it caused a global outbreak in over 110 countries, most of which had no infection history till then, and World Health Organization (WHO) declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) in July 20224. The strain in the 2022 outbreak was categorized as Clade II, causing milder disease5. Independent of this outbreak, MPXV Clade I, showing more severe symptoms to infected people with 4-11% reported mortality rate, caused the largest surge ever recorded in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) from 20236,7,8, resulting in WHO declaring MPXV infection a PHEIC in August 20249. Given such frequent MPXV outbreaks in recent years, and potentially also in the future because of the lower number of smallpox vaccinated people globally, medical countermeasures against MPXV infection are urgently needed.

Currently, limited drugs are used for treatment against MPXV infection. Tecovirimat and brincidofovir are available for clinical treatment in the USA and EU. Tecovirimat is a virion formation inhibitor that targets orthopoxviral F13L protein to suppress virus spread, whereas brincidofovir is a prodrug of a nucleotide analog, cidofovir, which inhibits viral DNA replication in host cells10,11,12. Vaccinia Immune Globulin Intravenous (VIGIV), a purified immune globulin derived from the plasma of donors who received vaccinia virus (VACV)-based vaccines, is an additional therapeutic used for blocking viral infection13. However, their effectiveness in MPXV-infected human patients has not been well-documented.

Upon infection, orthopoxviruses have two distinct infectious forms, designated mature virions (MV) and extracellular enveloped virions (EEV)14. Surface molecules on these virions are theoretical drug targets for blocking MPXV infection. Studies using mouse models of VACV infection suggest that the viral surface proteins A13, A17, A27, A28, D8, H3, and L1 on MV, and A33 and B5 on EEV are involved in target cell infection14. A subsequent study on human subjects who had recovered from MPXV infection or received VACV-derived vaccines identified VACV A27, D8, H3, and L1 on MV and A33 and B5 on EEV as targets for neutralizing antibodies against orthopoxvirus infection15. They successfully produced human monoclonal antibodies against these VACV antigens that cross-protected wide range of orthopoxviruses, but most of them and even their mixed antibody pools showed at least 1–2 log lower activity to neutralize MPXV, compared with VACV. Another report also indicated relatively low MPXV-neutralizing activities of the antisera and the monoclonal antibodies induced in rhesus macaques immunized with VACV16. These results speculate that using MPXV antigens instead of the VACV antigens would induce antibodies having higher neutralizing activity against MPXV infection. In the above reports, VIGIV also exhibited lower MPXV-neutralizing activity in vitro compared to that against VACV16. Additionally, limited efficacy of VIGIV was indicated in vivo for treating the ectromelia virus infection model by the same research group17. In addition to the uncertain efficacy for MPXV infection, VIGIV has limitations of supply and exhibits lot-to-lot variability. Thus, developing advanced technologies to overcome these limitations and to produce antibodies against MPXV infection is imperative.

Heavy-chain antibodies are unique immunoglobulins that are naturally produced by animals such as camelids. The variable domain of the heavy-chain antibody (VHH) has one-tenth of the molecular weight of a conventional IgG but exhibits an equivalent antigen-binding activity. As VHHs are advantageous due to their unique antigen recognition ability and can be easily modified to prepare multivalent forms that can augment the neutralizing activity, they have been applied drugs aiming for the treatment of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, cancer, and rheumatoid arthritis. Although there is no VHH-based drug approved so far in the field of infectious diseases, the above-mentioned characteristics indicate that VHHs are potential drug modalities for developing antiviral agents18,19. In this study, by employing the MPXV surface antigens as targets, we developed anti-MPXV VHHs by taking advantage of its feature that is easy-modifiable to enhance the activity.

Results

Screening of single-domain antibodies by targeting MPXV antigens

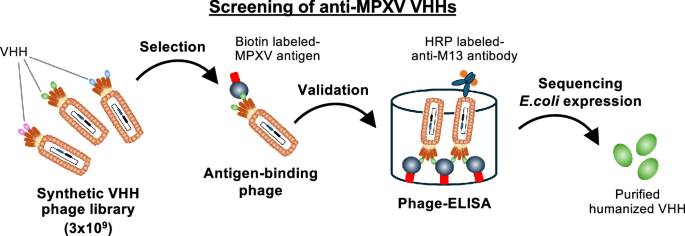

Given the relatively low cross-neutralizing activity of anti-VACV antibodies to block MPXV infection15, we employed MPXV surface antigens to generate antibodies. We prepared recombinant antigen proteins of the ectodomains derived from MPXV, A35R and B6R, which were displayed on EEV (corresponding to VACV A33 and B5 antigens), and A29L, E8L, H3L and M1R, which were expressed on MV (corresponding to VACV A27, D8, H3, and L1 antigens). A synthetic humanized antibody library, with a complexity of 3 × 109 VHHs presented on phage, was incubated with each biotin labeled-MPXV antigen, followed by washing out unbound phages and recovering the phages bound to the target antigen (Fig. 1A). After three to four rounds of phage display panning, enriched phage clones were validated using phage ELISA to examine their binding to the MPXV antigen. VHH sequences were identified from the phagemids extracted from the validated clones. We selected 5, 4, 12, 9, 15, and 7 clones as candidate binder VHHs for MPXV A29L, A35R, B6R, E8L, H3L, and M1R, respectively. We successfully produced each of 4, 3, 8, 5, 5, and 3 VHH clones as a histidine-tagged recombinant protein in the soluble fraction of the E. coli expression system for purification using an affinity column (see Materials and Methods in detail) (Supplementary Fig. 1). Alignment of the CDR sequences of the VHH clones revealed no notable conserved motifs, possessing high sequence diversity. In particular, CDR3 exhibited considerable diversity in both length and sequence variation. (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Graphical summary of anti-MPXV VHHs screening. Phage library presenting 3 × 109 VHHs was incubated with each biotin labeled-MPXV antigen (either A29L, A35R, B6R, E8L, H3L, or M1R), followed by washing unbound phages. After 3–4 rounds of phage display panning, antigen-bound phages were obtained. Binding of the obtained phage clones to the target antigen was validated by phage ELISA. VHH sequences were identified from the phagemids extracted from the validated clones, and monoclonal VHHs were expressed in periplasm fractions of E. coli BL21.

Binding affinity of VHHs to MPXV antigens

The binding affinity of these purified VHHs to the target MPXV antigens was evaluated by using a digital surface plasmon resonance detection system. Each MPXV antigen was immobilized on a sensor cartridge by amine-coupling, and was then reacted with the purified VHHs as analytes. The specific reaction against MPXV antigens was determined in all analytes by detecting the response against immobilized bovine serum albumin as a reference. The numbers of positive binders against MPXV antigens were 2, 3, 8, 1, 3, and 3 clones for A29L, A35R, B6R, E8L, H3L, and M1R, respectively. The KD values of VHH clones ranged from 676-2,060, 235-677, 289-4,390, 567, 548-3,310, and 134-326 nM for A29L, A35R, B6R, E8L, H3L, and M1R, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 1).

Improved neutralizing activity of bivalent VHHs

We evaluated the neutralizing activity of VHHs in a cell-based MPXV infection assay. Each VHH (10 μg/mL) was mixed with MPXV (Clade II Liberia strain, 100 PFU), which was then treated to VeroE6 cells for 3 days, and the plaque formation was quantified to monitor virus infection. As shown in Fig. 2, treatment with most VHHs did not show a marked reduction in plaque formation, but only anti-M1R VHH clone A8 indicated approximately 30% reduction in plaque formation with a statistical significance (Fig. 2).

MPXV (Liberia, 100 PFU) pre-incubated with each anti-MPXV VHH (10 μg/mL) for 16–18 h was inoculated to VeroE6 cells which were seeded in 24-well plate at 1 × 105 cells/well for 3 days. After the cells were washed, fixed with formaldehyde, and stained with 0.1% crystal violet, number of formed plaques was counted to calculate the plaque formation rates. Relative plaque formation rate was determined by setting that in media-treated control cells as 100%, are shown against VHH clones. Individual data for media-treated control (n = 17) and VHHs (n = 3) were plotted in the graph, and the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) was indicated. Dash line indicates 100% as the control level. Statistical analyses were performed with Mann-Whitney U test (vs Media, *p < 0.05).

We speculate that the absence or limited neutralizing activities of these VHHs may be due to insufficient affinities to the target antigen. The affinity of VHHs to the target can be improved via VHH manipulation, such as by preparing tandem-repeat VHHs connected with a flexible linker20,21,22. We subsequently generated bivalent forms of the VHHs by conjugating two VHH regions in tandem with a (GGGGS)x3 linker, which were expressed in E. coli and purified (Fig. 3A). Although not all the bivalent VHHs were successfully expressed in the soluble fraction, we prepared nine bivalent VHHs, one against A29L, A35R, and E8L, respectively (clone bi-A29H7, bi-A35A9, bi-E8C3), three against H3L (clone bi-H3B1, bi-H3D12, bi-H3E12), and three against M1R (bi-M1A8, bi-M1C2, bi-M1G7) (Fig. 3B and Supplementary Fig. 4).

A Structure of a tandem repeat of VHHs (bivalent VHHs). The same VHHs were conjugated with a linker with the sequence, (GGGGS)x3. pelB: signal sequence to secrete the VHH into a periplasm fraction; 6xHis: poly histidine-tag; c-Myc: c-Myc tag; G4Sx3: flexible linker (GGGGS)x3. B Purified monomer and bivalent VHH was loaded on 4–12% SDS-PAGE and stained with CBB. The uncropped gel images are provided in Supplementary Fig. 4.

These bivalent VHHs showed at least 9-fold enhanced binding affinities to the target MPXV antigen compared to their corresponding monomers (Supplementary Table 2). Especially, bivalent forms of anti-M1R VHHs (clones bi-M1A8 and bi-M1C2) remarkably elevated the binding affinity by over 400- and 20,000-fold, with 485 and <6.67 pM KD, respectively (Fig. 4, Supplementary Fig. 5 and Supplementary Table 2).

Single cycle kinetics response was detected by SPR using anti-MPXV VHHs (4.12 – 333 nM) as analyte over recombinant MPXV antigens immobilized on a sensor cartridge as targets. Five concentrations of analytes with 3-fold serially dilution were applied (arrows), and the sensorgrams were described for A monomer (left) and bivalent (right) VHH clone M1A8 against MPXV M1R, and for B those of VHH clone M1C2 against MPXV-M1R. The binding curves (red lines) were fitted to a 1:1 Langmuir binding model and the fitting curves were described as black lines. Calculated KD are shown in the sensorgrams. All sensorgrams of the tested VHHs and their kinetics data of Rmax, ka, kd, and KD are summarized in Supplementary Fig. 2 and Table 2.

The neutralizing activity of these bivalent VHHs was evaluated using a plaque reduction assay in MPXV-infected cells. The VHHs, bi-M1A8 and bi-M1C2, clearly reduced the plaque formation by MPXV. In contrast, other bivalent VHHs showed no or limited anti-MPXV activity at least up to 1 μM (Fig. 5). Thus, the observed anti-MPXV neutralizing activities somewhat correlated with the affinity against the target viral antigen.

MPXV (Liberia, 100 PFU) pre-incubated with each anti-MPXV bivalent VHH (31.3–1000 nM) for 16–18 h was inoculated to VeroE6 cells which were seeded in 24-well plate at 1 × 105 cells/well for 3 days. The plaque formation rates were calculated by the same method in Fig. 2. Data were collected in triplicates (n = 3), and the graphs display individual data points, mean ± SEM, and a line indicating the mean value.

Generation of bispecific VHHs and their activities

To examine the effect of multivalent VHHs, we generated the bispecific VHHs using the same linker strategy (Supplementary Fig. 6A). Since only bivalent VHH clones against H3L except for M1R showed neutralization albeit weak activities (Fig. 5), and both of these antigens are express on the same virion type, MV, we employed H3L and M1R antigens as targets for bispecific VHHs. Using two monoclonal clones for each antigen, H3D12 and H3E12 (targeting H3L), and M1A8 and M1C2 (targeting M1R), we prepared bivalent VHHs using different combinations. The forms of H3D12-M1A8 and H3E12-M1A8 (from N to C-terminus in order) were not successfully expressed in soluble fraction of E. coli, whereas the remaining six constructs were purified (Supplementary Fig. 6B). These hetero-bivalent VHHs showed binding affinities for both H3L and M1R (Supplementary Fig. 6C and Supplementary Table 3), and the affinity was specific because each VHH monomer originally recognized only the target antigen but did not show any response to another antigen (Supplementary Fig. 6D). The affinities of the hetero-bivalent VHHs against M1R were almost equivalent to the affinity of VHH monomer (Supplementary Table 3). In contrast, all bivalent VHHs which are composed of M1C2 showed an enhanced affinity to H3L antigen (3-77-fold) (Supplementary Table 3), suggesting the possible conformational change of the anti-H3L VHH following tandemly linking to enhance the binding affinity. However, we did not observe the apparent improvement of neutralizing activity by these hetero-bivalent formation, as tested in the plaque reduction assay using the same method as described for data obtained in Fig. 2 (Supplementary Fig. 6E). We speculate that the remarkable elevation of binding affinity to a single antigen (as seen with 400- and 20,000-fold elevation by homo-bivalent anti-M1R VHHs in Fig. 4) may be effective to improve the neutralizing activity.

Epitope analysis of anti-MPXV M1R bivalent VHHs

To analyze the epitopes of the anti-M1R VHHs, a competition binding assay was performed by using SPR method (Fig. 6A). Each bivalent anti-M1R VHH was immobilized as a ligand (primary VHH) on a sensor cartridge, and the recombinant MPXV M1R antigen was applied to bind the primary VHHs. The secondary VHHs or the buffer was then applied to examine the binding response: An elevated response indicates that the secondary VHH has different epitope from the primary VHH, whereas no response indicates the competition of the secondary VHH with the primary VHH through the same or overlapped epitope (Fig. 6A). As shown in Fig. 6B, application of bi-M1C2 and bi-M1G7 as secondary VHHs showed elevated responses onto the M1A8-antigen-bi-M1A8 complex compared to the buffer or bi-M1A8 (left); that of secondary bi-M1A8 and bi-M1G7 showed higher response onto the M1A8 antigen-bi-M1C2 complex than that of the buffer or bi-M1C2 (center); that of bi-M1C2 and bi-M1A8 showed elevation in response from the buffer or bi-M1G7 (right). These data indicated that all three anti-M1R VHHs, bi-M1A8, bi-M1C2, and bi-M1G7 recognize different regions in M1R antigen.

A Schematic representation for the experimental design using a SPR method. B Competition binding of anti-MPXV M1R bivalent VHHs on sensor cartridge coupled with a primary antibody bi-M1A8 (left), bi-M1C2 (middle) or bi-M1G7 (right) by SPR with a classical sandwich method. Recombinant MPXV M1R was applied to bind the primary antibody, subsequently the bivalent VHHs were applied as secondary antibody analytes. Sandwiched reactions indicate the pair of the primary-secondary antibody has different epitope. C Comparisons of bivalent VHHs binding affinity against deglycosylated M1R protein. M1R protein was treated with PNGase F and the deglycosylation was confirmed by SDS-PAGE (Supplemental Fig. 7B). The deglycosylated M1R (M1R-DG) was coupled with a sensor cartridge, and the binding affinity of the bivalent VHHs were evaluated by SPR with a single cycle kinetics method as same as in Fig. 4.

The MPXV M1R antigen is a type I transmembrane protein that has three predicted N-glycosylation sites, migrated as several bands of glycosylation forms in SDS-PAGE (Supplementary Fig. 7A). To analyze the impact of the glycosylation against binding ability of the VHH, VHHs affinity was evaluated by SPR against the deglycosylated M1R antigen, by treatment with Peptide N-Glycosidase (PNGase) F; its deglycosylation was confirmed by SDS-PAGE (Supplementary Fig. 7B). The deglycosylated protein was immobilized to a sensor cartridge, and the bivalent anti-M1R VHHs were analyzed as analytes. As shown in Fig. 6C, bi-M1A8 and bi-M1G7 showed almost the identical affinities with the deglycosylated forms of M1R to that with glycosylated M1R. On the other hand, bi-M1C2 showed over 40-fold lower affinity to deglycosylated M1R, compared to glycosylated M1R (Fig. 6C and Supplementary Table 2), suggesting that bi-M1C2 partially recognizes a glycosylation site of M1R.

Cross-reactivity of anti-MPXV VHHs for orthopoxviruses

To assess the breadth of cross-reactivity of bivalent anti-MPXV M1R VHHs to orthopoxviruses, we evaluated the neutralizing activities against MPXV Clade I (Zr-599 strain), MPXV Clade II (Liberia strain), cowpox virus (CPXV) and VACV by performing plaque reduction assay. The bivalent anti-M1R VHHs, bi-M1A8 and bi-M1C2, showed equivalent neutralizing activities against both Clade I and II MPXV strains, and against CPXV (Fig. 7). In contrast, although the VHHs inhibited VACV infection in a dose-dependent manner, their effects were weaker compared to those against MPXV strains and CPXV (Fig. 7).

MPXV Zr-599 (Clade I), MPXV Liberia (Clade II), CPXV or VACV (each 100 PFU) pre-incubated with anti-MPXV bivalent VHH for 16–18 h was inoculated to RK13 cells seeded in 24-well plate at 1 × 105 cells/well for 3 (MPXV and CPXV) or 4 days (VACV). The plaque formation rates were calculated by the same method in Fig. 2. Data were collected in triplicate (n = 3), with individual data points plotted on the graph. The mean ± SEM and fitted curves are also shown. Fifty percent inhibitory concentration (IC50) was determined by using GraphPad Prism 9 software.

Neutralizing effect of anti-MPXV M1R VHH on re-infection of MPXV produced from infected cells

Neutralizing activity of VHHs was evaluated by pre-incubating VHHs with virus inoculum for 16 h, then treating cells with this mixture, and culturing cells for another 3 days to detect plaque formation, following the experiment described previously23. This assay evaluates virus neutralization upon the primary infection of the cells, but not upon the second or subsequent infections by the virus produced from infected cells to reinfect new cells for spread. To evaluate the effect of the anti-MPXV M1R VHH bi-M1A8 on reinfection, we treated cells with the VHH after MPXV inoculation for 1 h, and detected plaque formation for 3 days (Fig. 8A, Posttreatment). We also performed the assay against the primary infection by pretreating the VHH with MPXV inoculum (Fig. 8A, Pretreatment). As a result, post-treatment with bi-M1A8 significantly suppressed plaque formation at the level equivalent to that for pre-incubation (Fig. 8B). This data indicates that the anti-MPXV VHH bi-M1A8 neutralized both the primary and the secondary (or subsequent) viral infection.

A Experimental schedules of the assays in which VHH bi-M1A8 were wither pretreated to MPXV inoculum (Pre) or treated to VeroE6 cells that were already inoculated with MPXV and washed (Post). B Plaque reduction assay was performed as shown in Fig. 2 using MPXV (Zr-599, 100 PFU) and anti-MPXV VHH bi-M1A8 (final 0.5 μM). Individual data (n = 3) were plotted in the graph, and the mean ± SEM was indicated. Statistical analyses were performed with one-way ANOVA analysis followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test (vs untreated, **p < 0.005).

In vivo protection of MPXV infection by anti-M1R VHHs

We assessed the anti-MPXV activity of anti-M1R VHH in an MPXV infection SCID mouse model. As a positive control experiment, mice were orally administered with tecovirimat, an anti-orthopoxvirus reagent, at 100 mg/kg starting one day prior to viral challenge with 10⁵ PFU of Clade I MPXV and continuously administered daily for five days (Fig. 9A). Viral infectious titer as well as MPXV DNA in the lung recovered at day five post-virus inoculation were clearly decreased by tecovirimat treatment compared with the vehicle control (DMSO/corn oil) (Fig. 9B, D), validating this experiment as a drug evaluation system. Mice were intranasally administered with 10 mg/kg M1A8 (monomer) or bi-M1A8 (bivalent) immediately prior to MPXV challenge and were continuously administered with the VHHs once daily for the following four days (Fig. 9A). As the case with tecovirimat, the levels of viral infectious titer as well as MPXV DNA in the lung tissues of the mice treated with M1A8 and bi-M1A8 were significantly lower than that in vehicle control (PBS), with a greater reduction by bi-M1A8 compared to by M1A8 (Fig. 9C, E). In the histopathological examination, alveolar structure was lost with the infiltration of necrotic cell debris and neutrophils in the lung of vehicle-treated mice. Vasculitis was marked with perivascular edema and perivascular inflammation. The bronchial epithelium proliferation, degeneration, and necrosis/apoptosis was observed, and the bronchial lumen was narrowed by these debris. Additionally, the MPXV antigen-positive cells were distributed around the bronchi and vessels (Fig. 9F). In contrast, the normal structure of lung was observed in the tecovirimat- or bi-M1A8-treated mice, and the MPXV antigen-positive cells were rarely observed in both lung tissues (Fig. 9F). Furthermore, to evaluate the suppression of viral dissemination beyond the site of inoculation, viral DNA levels in the liver were measured. In the livers of mice treated with bi-M1A8, MPXV DNA levels were lower compared to the control group, although the difference did not reach statistical significance (Supplementary Fig. 8B). These data suggest that the anti-M1R VHH could suppress viral dissemination in vivo.

A Schematic representation for the experimental design. SCID mice were intranasally challenged with 105 PFU of MPXV (day 0) and treated with or without tecovirimat (100 mg/kg, orally) or VHHs (M1A8, bi-M1A8, each 10 mg/kg, intranasally) daily at the indicated time points (day -1 to 4 for tecovirimat; day 0 to 4 for VHHs) (n = 5 per group). Tissues were collected on day 5 post-inoculation. MPXV infectious titers (PFU) in the lungs of mice treated with or without tecovirimat (B) or VHHs (M1A8, bi-M1A8) (C). MPXV DNA levels in the lungs of mice treated with or without tecovirimat (D) or VHHs (M1A8, bi-M1A8) (E). Individual data (n = 5) were plotted in the graphs, and the mean ± SEM was indicated. Statistical analyses were performed with two-tailed Student’s t-test (B, D) or one-way ANOVA analysis followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test (C and E), *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. F Histological (H&E, upper) and immunohistochemical staining of lung sections from each group using anti-MPXV rabbit serum (lower). Scale bars: 100 μm.

Discussion

In this study, we designed neutralizing VHHs against MPXV based on the single-domain antibody technology. In contrast to the conventional IgG which consists of a heterodimer with heavy and light chains and is difficult to generate functional multimers, the single-domain antibodies are advantageous in enabling easy manipulation for optimizing their activity and multitargeting. Additionally, while IgG production is limited to the use of mammalian cells, which requires high costs for large-scale production, the single-domain antibody can be produced using bacteria, and is therefore, cost-effective. We identified tandem-repeated bivalent VHHs that can be produced using E. coli and show anti-MPXV neutralization activity in an MPXV infection assay.

The monomeric VHHs showed nil or limited neutralizing activities in spite their target antigen binding affinity being approximately 100 nM of KD. We speculate that the possible reasons include the relatively low affinity of monomeric VHHs to antigens compared to conventional IgGs, and the affinity maturation of the VHHs against M1R by multimerization remarkably enhanced their function. As MPXV A29L, A35R, B6R, H3L, and M1R antigens were reported to form multimer24,25,26, developing multimeric VHHs against these antigens could provide a distinct advantage in molecular recognition. Among the VHHs evaluated, only the bivalent anti-M1R VHH showed a neutralizing effect against MPXV. Also, anti-orthopoxvirus antibodies reportedly induce the effector function via Fc region-mediated complement engagement15,16,27. As VHHs generated in this study did not have an Fc region, the antiviral effect of anti-M1R VHHs was independent of the effector function.

The bivalent anti-M1R VHH showed neutralizing activity when treated after virus inoculation. L1 in VACV (ortholog of M1R) binds an unidentified cell surface antigen28 and is a component of the entry-fusion complex, which involves membrane fusion and core entry29. Thus, the VHH may inhibit virus attachment to cells and/or virus fusion during its cell entry. The reason why functional VHHs were obtained only against M1R, among the six MPXV surface antigens, remains unclear, but M1R on MV may have a major contribution to MPXV infection in cells. Recently, it was reported that the mRNA vaccine only coding MPXV M1R could induce MPXV neutralizing activity in vitro and protect mice from VACV challenge26. It was also reported that a pseudovirus nanoparticle displaying VACV L1 protected mice from the mortality by VACV infection30. Another study reported that the chimeric macromolecule antibody consisting of mouse anti-M1R monoclonal IgG fused with another anti-M1R scFv showed effective MPXV neutralization in the presence of complements31. These studies are consistent with our conclusion showing the relevance of MPXV M1R as a target for producing protective VHHs. On the other hand, generated hetero-bivalent VHHs did not have a neutralizing effect on MPXV, although they had bispecific antigen recognition. It may be because the antibody affinity to each antigen was relatively low compared to homo-bivalent VHH and was insufficient for neutralization. Even though they lack neutralizing activity, the VHHs would be alternatively useful for generating antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) by linking appropriate membrane-disrupting payloads such as amphotericin B and polymyxin B32. So far, only a few studies have reported the development of VHHs against orthopoxviruses, including those against VACV L1, MPXV A29L, and MPXV A35R33,34,35, however, all these studies did not examine the neutralizing activity but only observed their affinity to target antigens. Concurrently with our study, it was reported that a VHH antibody targeting MPXV M1R exhibited neutralizing activity against MPXV in vitro and suppressed VACV infection in vivo36. Given that the reported anti-M1R VHH and the VHHs in this study exhibit opposite patterns of in vitro cross-neutralizing activity against MPXV and VACV36, it is likely that these antibodies possess different properties. However, these independent findings from different research groups further support the potential of VHH antibodies and M1R as promising targets for antiviral intervention. In the future, elucidating the neutralizing epitopes would be important for understanding the effective neutralization of MPXV.

Limitations of this study include that the infection assay employed MPXV inoculum extracted from infected cells, which was likely dominated by MV; thus, we may have overlooked the effect of EEV-targeting VHHs. Also, among the antiviral effects of antibodies mediated by neutralization and complement-dependent effector function, this study only evaluated the neutralization activity in a cell-based infection assay since VHHs lack Fc, and did not address the VHH manipulation to render the effector function by adding Fc-fusion forms. Engineering VHHs into Fc-fusion formats may compensate for their inherent drawback of poor pharmacokinetics due to their low molecular weight.

We believe that reporting the present results in a timely fashion would also be of value, given the current situation of the MPXV outbreak that demands a new strategy for drug development. This study provides one of the VHH modification strategies for enhancement and multitargeting against viruses. These technologies can also be adapted to other viral targets; the multitargeting VHHs and their conjugates represent new modalities for combating emerging viruses.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

VeroE6 and RK13 cells were cultured in 5% CO2 at 37 °C in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, FUJIFILM Wako 044-29765) containing 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS, NICHIREI Biosciences 174012). Cells were derived from the American Type Culture Collection (CRL-1586).

Recombinant MPXV antigen proteins

Recombinant MPXV antigen proteins A29L (Ser21-Glu110 of QNP13733.1 in E.coli, Sino Biological 40891-V08E)37, A35R (Arg58-Thr181 of EPI_ISL_13052264 in HEK293, Sino Biological 40886-V08H)37,38, B6R (Tyr18-His279 of QNP13760.1 in HEK293, Sino Biological 40902-V08H)38, E8L (Met1-Thr275 of Q8V4Y0 in HEK293, RayBiotech 230-30232)39, H3L (Met1-Pro278 of QNP13688.1 in HEK293, Sino Biological 40893-V08H1)37,38 and M1R (Ala3-Gly183 of QNP13675.1 in HEK293, Sino Biological 40904-V07H)38 were used as target antigens. To confirm the product quality, recombinant proteins were loaded on 4–12% SDS Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue (CBB) as shown in Supplementary Fig. 5A. Biotinylated proteins were prepared by using EZ-LinkTM Sulfo-NHS-LC-LC-Biotin (Thermo Fisher 21338).

N-deglycosylation of MPXV M1R antigen protein

Recombinant M1R antigen protein was deglycosylated by treating 25,000 units/mL PNGase F (New England Biolabs P0704) for 24 h at 4 °C in non-denaturing reaction condition according to the manufacture’s instruction.

Preparation of viruses

MPXVs, Zr-599 (Clade I) and Liberia (Clade II) strains, CPXV (Brighton Red strain), and VACV (LC16m8) were prepared by extraction from infected cells40,41. RK13 cells were inoculated with each virus inoculum and cultured with DMEM containing 5% FBS for 4 to 7 days. The cells were then repeatedly frozen and thawed, subjected to centrifugation, and the supernatants were used as the virus inoculum. The viral titers were determined by plaque formation assay42. The serially diluted virus inoculum was inoculated with cells seeded in 24-well plate (1 × 105 cells /well), and cells were cultured for 3–4 days. Next, cells were fixed with 10% formaldehyde (FUJIFILM Wako 060-01667) for 1 h at room temperature and stained with 0.1% crystal violet, then the plaque in each well was counted.

Plaque reduction assay

VHH antibodies were pre-incubated with virus (50–100 PFU) for 16–18 h in 5% CO2 at 37 °C, and the mixtures were inoculated with cells seeded in 24-well plate (1 × 105 cells/well)23. The infected cells were cultured under the same conditions as described above for 3–4 days. Next, cells were fixed with 10% formaldehyde (FUJIFILM Wako 060-01667) for 1 h at room temperature and stained with 0.1% crystal violet. ImmunoSpot S6 Analyzer (Cellular Technology Limited) was used to automatically measure the plaque in each well. Fifty percent inhibitory concentration (IC50) was determined by using GraphPad Prism 9 (v9.5.0) software.

Generation of humanized single-domain antibodies

Three or four rounds of Phage Display selection were performed using biotinylated recombinant MPXV antigens A29L, A35, B6R, E8L, H3L, and M1R as targets. Synthetic humanized hsd2Ab VHH library NaLi-H143 containing 3 × 109 clones based on the phagemid vector pHEN2 was expressed on the surface of M13 phage. Phage Display allows to select VHHs recognizing the non-adsorbed antigen in a native form. The phages produced from each E. coli clone were used to perform a 384-well plate ELISA with HRP-conjugated anti-M13 antibody (GE Healthcare 27-9421-01) and a colorimetric substrate (Tetra Methyl Benzidine, Thermo Fischer N301) (Phage ELISA). Phagemid was extracted from each phage ELISA-positive clone, and the VHH sequence was identified. The expression vector was transduced into E. coli BL21 (TaKaRa 9126), and single colony was cultured overnight at 37 °C by Terrific Broth medium (Sigma-Aldrich T9179) supplemented with 2%(w/v) glucose (FUJIFILM Wako 079-05511). The overnight culture was diluted with the culture medium containing 0.1%(w/v) glucose and further cultured until it reached OD600 of 0.6–0.8. At this stage, 0.5 mM (final) IPTG (MS Tech PAL-IPTG-1000-5) was added to induce the expression of recombinant VHH in periplasm fraction and cells were further cultured for 6 h at 28 °C.

Purification of recombinant VHH antibodies

E. coli-expressed VHH was collected by centrifugation, and the pellet was re-suspended in 20 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), 500 mM NaCl, 5 mM imidazole, and 1 mM PMSF (Sigma-Aldrich 93482). The cell suspension was frozen and thawed twice, and 1 mg/mL lysozyme (Nacalai Tesque 19499-04) was added to cell suspension followed by 30 min incubation at 4°C. After centrifugation at 16,500 x g for 30 min at 4°C, periplasm fraction was collected from supernatant. The fraction was processed using a HisGraviTrap column (Cytiva 11003399), and histidine-tagged VHH was eluted using 300 mM imidazole-containing buffer. A Buffer of the eluate was changed to PBS by PD-10 column (Cytiva 17085101).

Generation of bivalent VHH antibodies

The coding region of each monoclonal VHH monomer was amplified by performing PCR using the following specific forward and reverse primers (Eurofins) with the restriction enzyme sites and a linker coding 3x tandem repeated amino acids GGGGS: NotI-Linker-VHH_F 5’- TTTGCGGCCGCAGGTGGCGGTGGTAGCGGTGGCGGGGGCAGCGGCGGTGGCGGCTCAATGGCGGAAGTGCAGCTGCAGGCTTCCGGGGGAGGATTTG-3’ and BamHI-His6-VHH_R 5’- TTTGGATCCTTATTAGTGATGGTGATGATGATGGCTACTCACAGTTACCTGCGTCCCCTGTCC-3’. PCR products were ligated into the monomeric VHH expression pHEN2 vectors at Not I (New England Biolabs R3189) and Bam HI (New England Biolabs R3136) sites. The structures of the monomer and bivalent VHH was described in Fig. 3A. The expression vector was transduced into E. coli BL21, and the bivalent VHHs were expressed and purified in the same manner as the VHH monomer.

SDS Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE)

The solution containing recombinant protein or purified VHH was denatured by boiling, resolved by conducting SDS-PAGE using 4–12% resolving Bolt Bis-Tris gels (Thermo Fisher NW4120) and MES Running Buffer (Thermo Fisher B0002), and stained with CBB using Simply BlueTM Safe Stain (Thermo Fisher LC6065). Spectra Multicolor Broad Range Protein Ladder (Thermo Fisher 26634) was used as a protein marker.

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR)

The binding affinity of each VHH antibody to the target antigen was determined using the Alto high throughput digital SPR system (Nicoya). Briefly, each MPXV antigen (20 μg/mL in Acetate, pH4.5) was immobilized on a sensor cartridge (500-1500 RU, Nicoya KC-CBX-CMD-16) using the amine-coupling method, and the affinities of analytes were evaluated by single-cycle kinetics analysis in a running buffer of PBST (PBS + Tween-20, pH7.4, Nicoya ALTO-R-PBST) with 10 mM EDTA. Specific SPR response of each analyte was evaluated by subtraction of the response against BSA-coupled sensor. The binding curve of the SPR response was fitted to a 1:1 Langmuir binding model, and the kinetics parameters were analyzed in the data sets with a chi² value less than 10% of the corresponding Rmax, indicating good curve fitting. Binding curves were obtained, and the raw numerical data were exported as CSV files. The curves were subsequently plotted as graphs using Microsoft Excel.

Competition binding assay for epitope analysis of anti-MPXV M1R VHHs

The competition binding assay was performed using the Alto high throughput digital SPR system. The primary VHH (100 μg/mL in Acetate, pH4.5) was immobilized on a sensor cartridge using amine-coupling method. MPXV M1R recombinant antigen protein (0.5 μM) was applied on the coupled primary VHH for 200 s, and then 100 nM of secondary VHH was applied immediately for 200 s. Binding curves were obtained, and the raw numerical data were exported as CSV files. The curves were subsequently plotted as graphs using Microsoft Excel.

In vivo evaluation using MPXV infection mouse model

All procedures of the animal experiments were approved by the Animal Experiment Ethics Committee of National Institute of Infectious Diseases (124140-II) and adhered to institutional ethical guidelines. We have complied with all relevant ethical regulations for animal use. In vivo antiviral efficacy of the anti-M1R VHH (M1A8 and bi-M1A8) was evaluated in 7-week-old male CB17/Icr-Prkdcscid/CrlCrlj mice (The Jackson Laboratory). Following anesthesia with isoflurane, mice were intranasally administered 10 mg/kg of VHH in a 20 μL volume. Control animals received an equivalent volume of PBS via the same route. After 30 min, mice were anesthetized using a mixture of medetomidine (0.3 mg/kg), midazolam (4.0 mg/kg), and butorphanol (5.0 mg/kg) administered intraperitoneally, and 105 PFU of MPXV (Zr-599, 10 μL) was intranasally inoculated. Anesthesia was antagonized with atipamezole (10 mL/kg, i.p.), administered after virus inoculation. VHH was treated once daily for five consecutive days. As a positive control for efficacy, tecovirimat was administered orally at a dose of 100 mg/kg (100 μL per mouse) once daily for six consecutive days, starting one day prior to MPXV inoculation. For the vehicle control group, an equal volume of 5% DMSO in corn oil was administered in the same manner. Body weights were monitored daily, with a loss exceeding 20% of baseline considered a humane endpoint.

On day five post-challenge, euthanasia was conducted via exsanguination under isoflurane anesthesia, followed by the collection of lung and liver samples. Lung tissues were homogenized in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, and serial dilutions were used to infect RK13 cells for viral plaque quantification. A part of lung tissues was paraffin-embedded, sectioned, and subjected to hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining as well as immunohistochemical staining using anti-MPXV rabbit antiserum (1:200). The antiserum was obtained from rabbits immunized with heat-inactivated MPXV (Zr-599 strain). The images were acquired using the Olympus SLIDEVIEW™ VS200 microscope (Olympus). Tissue homogenates including lung and liver were also subjected to qPCR to detect MPXV DNA using the following primers and probe44: Forward primer (B7R): 5’-ACGTGTTAAACAATGGGTGATG-3’, Reverse primer (B7R): 5’-AACATTTCCATGAATCGTAGTCC-3’, Probe (B7R): FAM -5’-TGAATGAATGCGATACTGTATGTGTGGG-3’-BHQ1.

Statistics and reproducibility

Plaque reduction assays of VHHs were performed in biological triplicates (n = 3). Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 9, and results are presented as bar graphs showing the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) with individual data points (Figs. 2 and 8B). Statistical analyses were conducted using the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test (Fig. 2) and one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test (Fig. 8B). Dose-response curves of bivalent VHHs were generated in GraphPad Prism 9 using mean ± SEM values with individual data points shown as line graphs (Fig. 5). Cross-neutralizing activity was also analyzed in GraphPad Prism 9, and fitted curves with individual data points and the mean ± SEM are shown in Fig. 7.

The in vivo experiments were conducted using five animals per group (n = 5). Viral titers or viral DNA levels in the lungs of individual animals were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 9, and bar graphs were generated displaying the mean ± SEM values along with individual data points in Fig. 9B-E. Statistical analyses were conducted using the two-tailed Student’s t-test (Figs. 9B, D) and one-way ANOVA analysis followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test (9 C and 9E).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information. Source data for the figures can be found in the supplementary data file.

References

-

Kozlov, M. Monkeypox goes global: why scientists are on alert. Nature 606, 15–16 (2022).

-

Thornhill, J. P. et al. Monkeypox Virus Infection in Humans across 16 Countries – April-June 2022. N. Engl. J. Med. 387, 679–691 (2022).

-

Titanji, B. K. Neglecting emerging diseases – monkeypox is the latest price of a costly default. Med 3, 433–434 (2022).

-

WHO Director-General declares the ongoing monkeypox outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern. 2022. Available from: https://www.who.int/azerbaijan/news/item/23-07-2022-who-director-general-declares-the-ongoing-monkeypox-outbreak-a-public-health-event-of-international-concern.

-

WHO 2022-24 Mpox (Monkeypox) Outbreak: Global Trends. 2024. Available from: https://worldhealthorg.shinyapps.io/mpx_global/.

-

Bunge, E. M. et al. The changing epidemiology of human monkeypox-A potential threat? A systematic review. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 16, e0010141 (2022).

-

Vakaniaki, E. H. et al. Sustained human outbreak of a new MPXV clade I lineage in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo. Nat. Med. (2024).

-

WHO Mpox (monkeypox) – Democratic Republic of the Congo. 2023. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2023-DON493.

-

WHO Director-General declares the ongoing monkeypox outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern. 2024. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/14-08-2024-who-director-general-declares-mpox-outbreak-a-public-health-emergency-of-international-concern.

-

Duraffour, S. et al. ST-246 is a key antiviral to inhibit the viral F13L phospholipase, one of the essential proteins for orthopoxvirus wrapping. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 70, 1367–1380 (2015).

-

Hutson, C. L. et al. Pharmacokinetics and Efficacy of a Potential Smallpox Therapeutic, Brincidofovir, in a Lethal Monkeypox Virus Animal Model. mSphere 6, e00927 (2021).

-

Parker, S. et al. Efficacy of therapeutic intervention with an oral ether-lipid analogue of cidofovir (CMX001) in a lethal mousepox model. Antivir. Res. 77, 39–49 (2008).

-

CDC Clinical Treatment of Mpox. 2025. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/mpox/hcp/clinical-care/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/mpox/clinicians/treatment.html.

-

Moss, B. Smallpox vaccines: targets of protective immunity. Immunol. Rev. 239, 8–26 (2011).

-

Gilchuk, I. et al. Cross-neutralizing and protective human antibody specificities to Poxvirus Infections. Cell 167, 684–94.e9 (2016).

-

Noy-Porat, T. et al. Generation of recombinant mAbs to vaccinia virus displaying high affinity and potent neutralization. Microbiol. Spectr. 11, e0159823 (2023).

-

Tamir, H. et al. Synergistic effect of two human-like monoclonal antibodies confers protection against orthopoxvirus infection. Nat. Commun. 15, 3265 (2024).

-

Li, M. et al. Broadly neutralizing and protective nanobodies against SARS-CoV-2 Omicron subvariants BA.1, BA.2, and BA.4/5 and diverse sarbecoviruses. Nat. Commun. 13, 7957 (2022).

-

Lu, Y. et al. Multivalent and thermostable nanobody neutralizing SARS-CoV-2 Omicron (B.1.1.529). Int. J. Nanomed. 18, 353–367 (2023).

-

Huo, J. et al. Neutralizing nanobodies bind SARS-CoV-2 spike RBD and block interaction with ACE2. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 27, 846–854 (2020).

-

Schoof, M. et al. An ultrapotent synthetic nanobody neutralizes SARS-CoV-2 by stabilizing inactive Spike. Science 370, 1473–1479 (2020).

-

Xiang, Y. et al. Versatile and multivalent nanobodies efficiently neutralize SARS-CoV-2. Science 370, 1479–1484 (2020).

-

Tomita, N. et al. Evaluating the immunogenicity and safety of a smallpox vaccine to monkeypox in healthy Japanese adults: a single-arm study. Life (Basel) 13, 787 (2023).

-

Chang, T. H. et al. Crystal structure of vaccinia viral A27 protein reveals a novel structure critical for its function and complex formation with A26 protein. PLoS Pathog. 9, e1003563 (2013).

-

Su, H. P. et al. The structure of the poxvirus A33 protein reveals a dimer of unique C-type lectin-like domains. J. Virol. 84, 2502–2510 (2010).

-

Zuiani, A. et al. A multivalent mRNA monkeypox virus vaccine (BNT166) protects mice and macaques from orthopoxvirus disease. Cell 187, 1363–73.e12 (2024).

-

Zhao, R. et al. Two noncompeting human neutralizing antibodies targeting MPXV B6 show protective effects against orthopoxvirus infections. Nat. Commun. 15, 4660 (2024).

-

Foo, C. H. et al. Vaccinia virus L1 binds to cell surfaces and blocks virus entry independently of glycosaminoglycans. Virology 385, 368–382 (2009).

-

Bisht, H. et al. Vaccinia virus l1 protein is required for cell entry and membrane fusion. J. Virol. 82, 8687–8694 (2008).

-

Huang, P. et al. A Pseudovirus nanoparticle displaying the Vaccinia Virus L1 protein elicited high neutralizing antibody titers and provided complete protection to mice against mortality caused by a Vaccinia virus challenge. Vaccines 12, 846 (2024).

-

Ren, Z. et al. Identification of mpox M1R and B6R monoclonal and bispecific antibodies that efficiently neutralize authentic mpox virus. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 13, 2401931 (2024).

-

Regen, S. L. Membrane-disrupting molecules as therapeutic agents: a cautionary note. JACS Au 1, 3–7 (2021).

-

Meng, N. et al. Screening, expression and identification of nanobody against Monkeypox Virus A35. R. Int. J. Nanomed. 18, 7173–7181 (2023).

-

Walper, S. A. et al. Development and evaluation of single domain antibodies for vaccinia and the L1 antigen. PLoS One 9, e106263 (2014).

-

Yu, H. et al. In vitro affinity maturation of nanobodies against Mpox Virus A29 protein based on computer-aided design. Molecules 28, 6838 (2023).

-

Yang, X. et al. Identification of neutralizing nanobodies protecting against poxvirus infection. Cell Discov. 11, 31 (2025).

-

Moraes-Cardoso, I. et al. Immune responses associated with mpox viral clearance in men with and without HIV in Spain: a multisite, observational, prospective cohort study. Lancet Microbe 5, 100859 (2024).

-

Chiuppesi, F. et al. Synthetic modified vaccinia Ankara vaccines confer cross-reactive and protective immunity against mpox virus. Commun. Med.4, 19 (2024).

-

Cohn, H. et al. Mpox vaccine and infection-driven human immune signatures: an immunological analysis of an observational study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 23, 1302–1312 (2023).

-

Akazawa, D. et al. Potential Anti-Mpox virus activity of Atovaquone, Mefloquine, and Molnupiravir, and their potential use as treatments. J. Infect. Dis. 228, 591–603 (2023).

-

Hishiki, T. et al. Identification of IMP Dehydrogenase as a potential target for anti-Mpox Virus agents. Microbiol. Spectr. 11, e0056623 (2023).

-

Saijo, M. et al. Virulence and pathophysiology of the Congo Basin and West African strains of monkeypox virus in non-human primates. J. Gen. Virol. 90, 2266–2271 (2009).

-

Moutel, S. et al. NaLi-H1: A universal synthetic library of humanized nanobodies providing highly functional antibodies and intrabodies. Elife 5, e16228 (2016).

-

Shchelkunov, S. N. et al. Species-specific identification of variola, monkeypox, cowpox, and vaccinia viruses by multiplex real-time PCR assay. J. Virol. Method 175, 163–169 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We thank Hybrigenics Services, FRANCE for providing the phage display-based synthetic humanized VHH library. We also thank Department of Pathology, National Institute of Infectious Diseases to use the instrument. This work was supported by The Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) (JP21fk0108427, JP23fk0108590, JP24fk0108660, JP25fk0310525), the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI (JP22K20780, JP24K02290, JP25K09951), the JST MIRAI program (JPMJMI22G1), and the Takeda Science Foundation. An illustration of a mouse was reproduced from “Research Net” (https://www.wdb.com/kenq/illust/mouse) with permission.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Xavier Hanoulle and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Gloryn Chia and Laura Rodríguez Pérez.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Akazawa, D., Shimojima, M., Park, ES. et al. Bivalent single-domain antibodies show potent mpox virus neutralization through M1R antigen. Commun Biol 8, 1073 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08494-x

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08494-x