Introduction

Various nuclear facilities generate radioactive waste effluents with varying compositions and quantities globally1. Among these wastes, isotopes such as Cs, Eu, Co, and Sr emerge as primary components, particularly in radioactive liquid waste. Due to their long half-lives (e.g., ¹³⁴Cs: 2.06 years; ¹³⁷Cs: 30.17 years; ⁹⁰Sr: 28.79 years) and interactions with water/soil, these isotopes pose significant environmental risks, especially following nuclear accidents, tests, and inadvertent leaks2,3,4. Long-lived isotopes like ¹³⁷Cs and ⁹⁰Sr accumulate in soil, plants, and water, posing persistent ecological threats2,5. The nuclear industry faces persistent challenges in treating wastewater contaminated with ¹³⁷Cs and ⁹⁰Sr, particularly after the 2011 Fukushima incident, which released large volumes of radioactive effluent6. Both radionuclides are highly soluble, which contributes to their mobility and persistence in the environment. 137Cs, in particular, often dominates the radioactive activity in nuclear waste7. The hazards associated with radionuclides in water pose severe risks to human health, particularly from radioactive fallout linked to nuclear plants and operations8. Additionally, global concern over heavy metal pollution is increasing, as these metals enter the environment through natural processes (e.g., volcanic eruptions, forest fires) and human activities (e.g., mining, industrial production)9. Treating wastewater containing radionuclides remains one of the nuclear industry’s most pressing challenges.

Cs+ is employed in photoelectric cells, vacuum tubes, and catalytic applications. The isotope ¹³⁷Cs, a gamma emitter, is used in radiotherapy and as a calibration source for radiation detectors10. Exposure to this radionuclide may induce cellular damage, increasing carcinogenic risk. Natural zeolites effectively adsorb Cs⁺ ions from aqueous solutions11. Sr compounds find applications in glass, ceramics, pyrotechnics, and palliative care for bone cancer pain. Due to its chemical similarity to calcium, Sr2+ can incorporate into bone tissue, potentially causing skeletal disorders.

Remediation of radioactive contaminants can be achieved through various methods, including micro-remediation12microbe-aided phytoremediation13 nano-bioremediation14 and systems biology15. Methods such as nanofiltration and reverse osmosis are proficient at eliminating multivalent ions, including Sr²⁺. Electrodialysis and membrane distillation have demonstrated potential, particularly in the treatment of radioactive wastewater16. Thermally treated natural zeolites exhibit improved adsorption capabilities17. Porous zirconium phosphate and layered metal sulfides exhibit remarkable efficiency and selectivity in the removal of Sr²⁺ from wastewater18.

Fungi, a diverse group of eukaryotic microorganisms (including molds, yeasts, and mushrooms), exhibit significant potential in biosorption due to their unique physical and biological characteristics19,20,21,22. Unlike living biomass, Dead fungal biomass offers additional advantages, including environmental resistance, toxicity tolerance, ease of regeneration, and efficient metal recovery23,24,25,26. The fungal cell membrane consists of a lipid bilayer (40% phospholipids and sterols) and proteins (60%), while the cell wall comprises polysaccharides (e.g., chitin, glucans), proteins, and lipids (80–90% of dry weight)21,23,27. These components contain functional groups (e.g., hydroxyl, carboxyl, amine, phosphonate) that bind metal ions28,29. Mechanisms of sorption in dead biomass include physical adsorption, ion exchange, chelation, and metal complexation27. Fungi demonstrate remarkable metabolic plasticity and polyextremotolerance, enabling survival in harsh environments, including those with low pH and high metal concentrations22. Their high cell wall-to-biomass ratio enhances metal-binding capacity, making them superior to other biosorbents21,30.

Fungal biomass, including Aspergillus niger and Rhizopus arrhizus, is a cost-effective and abundant alternative for removing Cs+ and Sr2+ from radioactive wastewater. These biosorbents have high surface area, efficient binding mechanisms, excellent selectivity, and perform well across various pH conditions31,32. They are biodegradable, environmentally friendly, and can achieve comparable or superior removal efficiencies compared to traditional adsorbents31,32. Sumalatha et al. (2022) found that agricultural waste-derived materials can effectively remove radionuclides, with 99% Sr²⁺ uptake achieved using KOH-activated peanut shell biochar (PSABC). Fungal biomass like Aspergillus flavus was also evaluated for simultaneous Cs⁺/Sr²⁺ removal using advanced kinetic/isotherm modeling33. Dulla et al. (2020)34 demonstrated that spent Gelidiella acerosa biomass achieved 96.4% Cu (II) removal via chemisorption. Khan et al. (2022)35 discovered that algal biosorbents like Nostoc sp. and Turbinaria vulgaris effectively remove heavy metals from industrial effluents, with 94.2% and 88.9% removal achieved under optimized acidic conditions. Recent studies reveal that Turbinaria vulgaris can effectively remove arsenic up to 92.12% efficiently under optimized conditions36.

Aspergillus flavus is a promising biosorbent for radionuclide removal due to its cell wall composition and high surface-area-to-volume ratio. Its dead biomass utility, scalability, and competitive biosorption of Cs⁺ and Sr²⁺ offer new biosorption concepts and insights into selective radionuclide recovery. Aspergillus flavus is a sustainable, eco-friendly sorbent that can be safely incinerated or vitrified, offering a promising alternative to synthetic alternatives in the circular economy.

This study investigates the potential of Aspergillus flavus biomass as a green method for the removal of Cs+ and Sr2+ ions (model long-lived fission products) from aqueous solutions. The parameters of the batch biosorption process, including ion concentration, solution pH, shaking time, and temperature, were also evaluated.

Materials and methods

Fungal strain and cultivation

The fungus Aspergillus flavus was identified and sourced from the soil microbiology Laboratory of the Soil and Water Research Department at the Egyptian Atomic Energy Authority (EAEA). The isolation and identification of Aspergillus flavus have been done as shown in a previous study37. The fungus was regularly maintained on Czapek-Dox’s agar medium38 containing: 20 g of sucrose, 2.0 g of NaNO3, 1.0 g of KH2PO4, 0.5 g of MgSO4, 0.5 g of KCl, 0.001 g of FeSO4, 0.001 g of CaCl2, agar 20 g and distilled water 1 L.

Production of Aspergillus flavus biomass

Aspergillus flavus was inoculated on flasks containing broth Dox medium. The flasks were then agitated on a horizontal orbital shaker at 25 °C at 150 rpm for 7 days. Harvested mycelium was autoclaved to obtain dead fungal biomass, filtered off, and washed with double-distilled water. Then, it was dried using the lyophilization technique and ground for subsequent use.

Instruments

The Fourier transform infrared spectra (FTIR) of fungal biomass were kept in the scope of 400–4000 cm−1 with an Agilent Cary 630 FTIR spectrometer (Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA). The thermal gravimetric analysis (TGA) of fungal biomass was performed using the Shimadzu DTG-60 thermal analyzer purchased from Shimadzu Kyoto, Japan. The platinum sample holder was used in the experiments. The experiment was conducted in a dynamic oxygen atmosphere with a heating rate of 20 °C/min and temperatures ranging from room temperature to 600 °C. The Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) surface area of fungal biomass was determined using the Nova 3200 series (USA). The scanning electron microscope with energy dispersive spectroscopy (SEM/EDS) analyses was performed with JEOL JSM-IT200 associated with an EDS detector, Japan. It is used to estimate the elemental composition to render a complete knowledge of the simplicity, distribution, and position of the fungal biomass. The investigated ions Cs+ and Sr2+ were determined using an atomic absorption spectrophotometer, 210VGP.

Factors controlling the biosorption process

Experiments utilized stable Cs⁺ (as CsCl) and Sr²⁺, (as Sr(NO₃)₂) analogs to simulate ¹³⁷Cs and ⁹⁰Sr behavior, avoiding radiation hazards while maintaining identical chemical properties. All biosorption procedures were conducted using a mixture of Cs+ and Sr2+ ions in one solution. Several pH levels from 1 to 8 were assessed to determine the influence of pH on the batch sorption process. The experiment was performed under controlled conditions with 0.02 g of dried biomass; 50 mg/L of each ion, Cs+, and Sr2+, was agitated on an orbital shaker at 125 rpm and 25 ± 1 °C. The influence of contact time on the biosorption process was investigated at 0 to 60 min intervals for a mixed solution of Cs+ and Sr2+ (50 mg/L of each ion) at pH 5 and a temperature of 25 ± 1 °C. The impact of the initial concentrations of Cs+ and Sr2+ on the biosorption process was evaluated at optimum conditions, within the 100 to 1000 mg/L range. The optimal pH and contact time values were obtained from the studies above using 0.02 g of dry biomass as a control experiment. The uncertainty of all measured data did not surpass ± 5%. The subsequent formulas were employed to ascertain the equilibrium absorption of dried biomass and the proportion of metal ion removal:

$${q_e}={text{ }}left( {{C_i}–{text{ }}{C_e}} right){text{ }}V/m$$

(1)

$${text{R }}left( {text{% }} right){text{ = }}frac{{{C_i} – {C_e}}}{{{C_i}}}{{ times 100}}$$

(2)

.

Where qe represents the equilibrium sorption of the dried Aspergillus flavus, mg⋅g−1, Ci is the initial concentration (mg/L); Ce is the final concentration (mg/L); m is the dried mass of the Aspergillus flavus in the reaction (g); V is the volume of the reaction mixture (L), R is the removal %.

Desorption and reusability of adsorbed metals

To determine which desorbing agents were most effective at removing Cs+ and Sr+2 ions from the Aspergillus flavus, they were independently tested. The desorbing solutions utilized were EDTA (0.1 mol/L), HNO3 (0.1 mol/L), H2SO4 (0.1 mol/L), NaOH (0.1 mol/L), and HCl (0.1 mol/L). In each experiment, 0.02 g of Aspergillus flavus was used for 100 ppm of Cs+ and Sr2+, and 10 mL of the desorbing solution was placed in an Erlenmeyer flask and shaken for 90 min at room temperature. The reusability of the dried biomass was evaluated through several adsorption and desorption cycles. The desorption procedure utilized an optimal concentration of desorbing agents for Cs+ and Sr2+, with adsorption efficiency assessed after each cycle by the Eq.

$$% Desorption=frac{{{text{Amount of metal ion desorbed}}}}{{{text{Amount of metal ion adsorbed}}}} times 100$$

(3)

.

Results and discussion

Characteristics of Aspergillus flavus

FTIR analysis

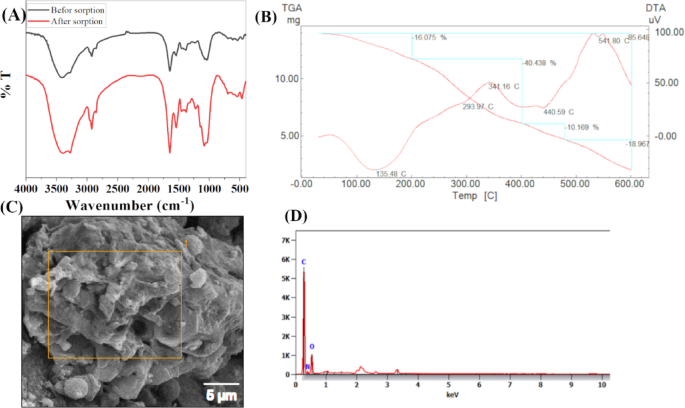

FTIR spectra were recorded to investigate the surface functional groups present in Aspergillus flavus biomass before and after biosorption of Cs+ and Sr2+. A comparative analysis reveals changes in specific functional group vibrations, indicating possible interactions or binding mechanisms between the biomass and the metal ions. The results also indicated that the bands at 3414, 2925, 1646, 1543, 1384, 1295, 1040, 869, 618, 540, and 452 were shifted to 3396, 3279, 2924, 2854, 1646, 1543, 1455, 1380, 1226, 1083, 697, 543 and 468 after sorption of Cs+ and Sr2+ ions and intensity changes of some peaks compared to the unloaded biomass. The FTIR spectra of the biomass before sorption of Cs+ and Sr2+ ions are illustrated in Fig. 1(A). Absorption at 3200–3400 cm−1 can be correlated to the O–H, –NH group stretch1,39. 2925 cm−1 is considered to be the stretching vibrations of –CH– in biomass40 while 1646 cm−1 corresponds to the binding vibrations of the C = C stretching double bond. C = O stretching implies that proteins play a key role in metal binding, likely through the –NH and –C = O groups. The broadening of the –OH/NH peak suggests hydrogen bonding alterations or direct interaction of hydroxyl groups with Cs⁺ and Sr²⁺. Absorption at 1000–1200 cm−1 can be correlated to the C–O/C–O–C stretching (carbohydrates, polysaccharides) slight reductions in polysaccharide-associated peaks (C–O–C) may indicate involvement of carbohydrate moieties in biosorption. Emergence or enhancement of bands in the 600–800 cm⁻¹ region could suggest the formation of metal–oxygen coordination bonds, typical in biosorption processes. Cs+ and Sr2+ ions -loaded biomass resulted in appearance of three peaks at 3279, 2854, and 1455 cm−1. These spectral changes confirm that metal ions are effectively interacting with functional groups on the fungal biomass, mainly involving hydroxyl, amine, carbonyl, and possibly carboxylic groups. The comparative FTIR analysis clearly demonstrates the biosorption capability of Aspergillus flavus biomass for Cs and Sr ions. Shifts in peak positions and intensities confirm the involvement of functional groups such as O–H, N–H, C = O, and C–O in metal binding. This supports the potential application of A. flavus in the biosorption of radioactive or heavy metal-contaminated environments.

(A) FT-IR spectrum, (B) Thermal analysis, (C) SEM, and (D) EDS chart of the Aspergillus flavus biomass.

Thermal analysis

Thermal analysis of Aspergillus flavus biomass revealed four stages of degradation, as reported in Fig. 1(B). The initial stage exhibited a weight loss of 16.075% due to the desorption of water molecules from the biomass’s external surface, occurring within a temperature range of 32 °C to 213 °C. The second stage ranges from 213 °C to 438 °C with partial weight loss of 40.43%, which is assigned to the degradation of the total lipids41. The third stage ranges from 438 °C to 500 °C with a partial weight loss of 10.169%, which could belong to the decomposition of the polysaccharide structure. The fourth stage ranges from 500 to 600 °C with partial weight loss of 18.97%42.

SEM/EDS

SEM micrographs and EDS spectra of Aspergillus flavus biomass are presented in Fig. 1(C). Apparent morphology was seen as a smooth surface with porous cavities; The EDS spectrum showed the presence of C and O peaks along Fig. 1(D). The presence of cell wall components in Aspergillus flavus biomass was probably the cause of the observed C and O peaks40.

Surface area

The nitrogen gas adsorption/desorption technique on Aspergillus flavus biomass has been utilized to determine the surface area. The total pore volume of Aspergillus flavus biomass is 0.0015 cm3 g-1. Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) surface area and average pore radius of the Aspergillus flavus biomass material are 9.65 ms g-1 and 18.55 Å, respectively. Based on these characterizations, it can be deduced that the ability of Aspergillus flavus biomass to act as a biosorbent material. Thus, the assessment of Aspergillus flavus biomass material sorption characteristics is measured as described in the following section.

Chemical stability

The chemical stability (% solubility) of Aspergillus flavus biosorbent was assessed at room temperature, with the results presented in Table 1. The results indicate that Aspergillus flavus biosorbent exhibited stability in deionized distilled water, mineral acids, and alkalis. Table 1 indicates that the Aspergillus flavus biosorbent has comparatively excellent chemical stability when assessed against various sorbents.

Sorption properties of Aspergillus flavus biomass

Effect of pH

Multiple tests were conducted to evaluate the pH effect on metal removal by Aspergillus flavus biomaterial across different pH levels, as illustrated in Fig. 2(A). The study investigated the influence of initial pH on the removal of Cs+ and Sr2+ ions by Aspergillus flavus, utilizing initial ion concentrations of 50 mg/L, at time 24 h, and a temperature of 25 ± 0.1 °C. The pH of the solution is directly correlated with the quantity of adsorbed ions. An increase in pH values results in a higher concentration of adsorbed ions.

The pH of the sorption medium influences the metal ion’s solubility, and the ionization state of the carboxylate, phosphate, and amino groups present on the cell wall of fungi43. Hydrogen and metal ions compete for binding sites, affecting metal ion biosorption. The high proton concentration at lower pH increases the positive charge density on binding sites, reducing metal ion biosorption. With rising pH, the negative charge density on the cell surface increases as the metal binding sites undergo deprotonation. Subsequently, the metal ions improve their competitiveness for the limited binding sites, hence enhancing biosorption44,45.

A significant rise in the percentage of Sr2+ ion biosorption was found at pH 5.0, reaching around ~ 90%. The significant reliance of Sr2+ ion biosorption on pH indicates that surface complexation is the dominant sorption mechanism over cation exchange30. For Cs+ ions, the highest level of biosorption was seen at pH 8, with a sorption 27%. Consequently, pH 5 was identified as the optimal pH for subsequent experiments.

(A) Effect of pH, (B) Effect of contact time on sorption of Cs+ and Sr2+ onto Aspergillus flavus, m: 0.02 g, V: 0.1 L, pH: 5, T: 20.1 °C.

Effect of contact time

Figure 2(B) demonstrates the impact of contact time on the adsorption of 100 mg/L Cs+ and Sr2+ ions onto Aspergillus flavus. The percentage of the prepared biomaterial uptake grew as the contact time increased until it achieved equilibrium. We observed the highest uptake percentage for all the examined ions at 15 min, which indicates that the rate of Cs+ and Sr2+ adsorption onto Aspergillus flavus is high. The sorption equilibrium is highest for Sr2+ ions, with a sorption percentage of 90%. Cs⁺ ions have a lower sorption equilibrium, with a percentage of 27%. The active sites on the adsorbent’s surface contribute significantly to the absorption percentage. The greater sorption of Sr2+ compared to Cs+ on the Aspergillus flavus surface is primarily due to the higher charge density, smaller ionic radius, and stronger complexation ability of Sr2+ with the functional groups on the Aspergillus flavus surface. These factors lead to more effective ion exchange and surface complexation for Sr2+, resulting in higher sorption than Cs+. For ion exchange adsorption of Cs+ and Sr2+, the potential of the cation in solution (i.e., the ratio of charge to the radius of the hydrated ion, Z/r) determines the interaction force between the adsorbent and ions. Table 2 shows the hydration radius and potential of ions. Thus, the order of selectivity for Sr2+ is greater than Cs+46.

Kinetic isotherm models

The resulting data were utilized to investigate the step that determines the rate of the sorption process. Equations (4) and (5) represent the pseudo-1st and pseudo-2nd order equations, respectively.

$$Ln({q_e} – {q_t})=Ln{q_e} – frac{{{K_1}}}{{2.303}}t$$

(4)

$$frac{t}{{{q_t}}}=frac{1}{{{K_2}q_{e}^{2}}}+frac{1}{{{q_e}}}t$$

(5)

.

The variable qe represents the quantity of metal ions adsorbed at equilibrium. The rate constants for the pseudo-1st and pseudo-2nd order equations are denoted as K1 and K2, respectively. The pseudo-1st order model, represented by Eq. (4), exhibits a linear relationship when plotting the logarithm of the difference between qe and qt against time, as shown in Fig. 3(A). The determined value of the quantity of metal ions sorbed, qe (calc.), was obtained from the intercept. However, it does not align with the experimental value, qe (exp.) presented in Table 3. This indicates that the pseudo-1st order kinetic model is unsuitable for the sorption of Cs+ and Sr2+ ions onto biomaterial.

The sorption of Cs+ and Sr2+ ions onto the biomaterial was examined using a pseudo-second-order model. This was done by charting the ratio of the amount of sorbed ions to the time elapsed (t/qt) against time (t), as described by Eq. (5). The resulting plots showed straight lines, as illustrated in Fig. 3(B). The qe (calc.) values were determined from the slope and closely matched the experimental values, qe (exp.). Table 3 shows the strong correlation coefficients achieved (R2 > 0.99) by applying the pseudo-second-order kinetic model. Hence, the pseudo-second-order kinetic model accurately corresponds to the experimental findings throughout the sorption process.

Plots of (A) pseudo-1st order and (B) pseudo-2nd order kinetic models for sorption of Cs+ and Sr2+ ions, and Nonlinear Langmuir and Freundlich isotherm plots for removing (C) Sr2+ and (D) Cs+ onto the Aspergillus flavus.

Effect of initial concentration

The equilibrium tests were performed to investigate the sorption of Cs+ and Sr2+ utilizing biomaterial at varying initial concentrations of Cs+ and Sr2+ (50 to 500 mg/L) under ideal conditions. Their distribution between the liquid and solid phases dictates the equilibrium state in the extraction of metal ions. The equilibrium data were examined using a nonlinear approach, specifically models developed by Langmuir and Freundlich. The isotherm of Langmuir isotherm is an essential model for precisely elucidating physical and chemical sorption phenomena. The Langmuir theory argues that sorption occurs at distinct homogeneous sites. Equation (6)47 shows the mathematical expression for this model’s nonlinear version.

$${q_e}=frac{{{K_L}{q_{hbox{max} }}{C_e}}}{{(1+{K_L}{C_e})}}$$

(6)

.

The variable qe represents the concentration of metal ions on the sorbent at balance, measured in milligrams per gram. Ce represents the metal ions concentration in the solution at equilibrium, measured in mg/L. qmax is the maximum amount of metal ions the sorbent can adsorb per gram, measured in milligrams per gram. KL is the Langmuir adsorption constant, measured in liters per milligram.

The second isotherm model is the Freundlich isotherm model. It states the existence of a heterogeneous adsorption surface with active spots exhibiting various energy levels. The Freundlich model is expressed by the Eq. (7)48,

$${q_e}={K_f}C_{e}^{{1/n}}$$

(7)

.

where KF (mg1−n Ln g−1) is the Freundlich constant, which is influenced by the amount of the sorbent, and 1/n represents the affinity of the binding sites. The findings from the isotherm studies are displayed in Fig. 3(C, D) and Table 3. Figure 3(C, D) displays the fitting curves of the isotherms, indicating that the Freundlich isotherm model is the most appropriate for the adsorptive removal of Cs+ and Sr+2 using biomaterial.

Sorption thermodynamics

The current system’s thermodynamic properties were determined to better understand the biosorption process’s thermodynamics. The change in Gibbs free energy (ΔG) determines randomness. The reaction occurs spontaneously if ΔG is negative at a specific temperature. The Van’t Hoff equation was utilized to calculate the thermodynamic parameters as follows:

$$Delta G= – RTln {K_L}$$

(8)

$$ln {K_L}=frac{{Delta S}}{R} – frac{{Delta H}}{{RT}}$$

(9)

.

where R = the universal gas constant, T = the system absolute temperature (K), and KL = the standard thermodynamic balance constant (L/g) defined by qe/Ce. Figure 4(A) illustrates the values of ΔH and ΔS used to calculate from the slope and intercept of a graph of Ln KL vs. 1/T, and the results are shown in Table 4.

(A) Ln KL Plot versus 1/T for removal of Cs+ and Sr2+, (B) impact of ions that interfere on Cs+, and Sr2+ removal (initial concentration of Cs+, and Sr2+: 25 mg/L. V/M = 2, pH = 5), (C) Recovery of Sr2+ and Cs+, (D) Reusability studies of Aspergillus flavus.

The ΔG values for Cs+ and Sr2+ ions were consistently negative at all temperatures. This suggests that the sorption processes occurred spontaneously. Moreover, the change in ΔG exhibited an upward trend as the temperature decreased, indicating that temperature played a significant role in the sorption process49. The fact that ΔH is positive suggests that Aspergillus flavus’s ion sorption was endothermic because it involved heat absorption. The ΔH values for Cs+ and Sr2+ metal ions indicate that the sorption of these metals onto Aspergillus flavus was physisorption, as the values did not exceed 40 KJ/mol. Furthermore, the positive ΔS value indicates an increase in randomness at the interface between Aspergillus flavus and the solution, as shown in Table 3.

Effect of interfering ions

We examined the impact of coexisting ions on removing Cs+ and Sr2+ by Aspergillus flavus by individually and collectively adding 25 mg/L of Na+, Ca2+, and Fe3+ ions to the solutions, as illustrated in Fig. 4(B). The impact of these ions on the mixture of Cs+ and Sr2+ was subsequently examined. We calculated the elimination percentage to evaluate the selectivity for Cs+ and Sr2+. The percentage removal of Cs+ diminished correspondingly with the concentration of the monovalent cation, Na+. Divalent cations, Ca2+, had a diminished effect on the removal percentage of Cs+. Unlike Cs+ and Sr2+, the divalent Ca2+ cation significantly influenced adsorption. Specifically, Ca2+, with chemical characteristics equivalent to those of Sr2+, significantly impeded Sr2+ adsorption. Meanwhile, Sr2+ adsorption was minimally influenced by monovalent cations. The competitive influence of cations on the adsorption of Cs+ and Sr2+ adhered to the sequence Na+ > Fe3+ > Ca2+ for Cs+ and Ca2+ > Na+ > Fe3+ for Sr2+.

Biosorbent desorption and reusability

The desorption process involves removing the adsorbate from the biosorbent surface, making the biosorbent material reusable in the treatment process. This work involved the desorption of Sr2+ and Cs+ from the Aspergillus flavus biosorbent surface, which had been previously loaded with these metal ions, utilizing a batch approach with 0.1 M various eluting agents, including H2SO4, HCl, HNO3, NaOH, and EDTA. The results demonstrated that HNO3 (0.1 M) is the most effective, achieving desorption percentages of 81.2% for Sr2+ and 71.5% for Cs+ Fig. 4(C).

The reusability of the biosorbent is a crucial factor influencing the biosorption system’s economic feasibility and minimizing the operational costs of the separation process. Figure 4(D) depicts the outcomes of the reusability investigations of Aspergillus flavus biosorbents. The biosorbent was regenerated using HNO3 (0.1 M) and reused efficiently for three cycles. A significant reduction in biosorption capacity (regenerated with HNO3, 0.1 N) was seen after more than three cycles, attributed to the decreased surface functional groups resulting from chemical regeneration and ongoing saturation of binding spots50,51.

Suggest a biosorption mechanism

The removal of metal ions by fungal biomass occurs through three mechanisms: chemical transformations52bioaccumulation9,23,30and biosorption53.

This study focuses on biosorption by Aspergillus flavus dead biomass, which exhibits enhanced metal uptake capacity52. The process involves surface complexation, where metal ions coordinate with electron-donating groups on the cell wall, forming stable chelates53 and ion exchange, where native cations are displaced by target metals, maintaining charge balance53. Cell wall adsorption dominates metal removal in dead biomass systems54. Figure 5 schematically illustrates these mechanisms for Cs+ and Sr+2 biosorption by Aspergillus flavus.

Diagram illustrating the biosorption of cesium and strontium from aqueous solution by A flavus biomass.

Comparison of sorption capacity

We compared our findings to those published in the literature to determine the prepared Aspergillus flavus biomass’s adsorption efficiency. The maximum adsorption capacity (qmax) of various adsorbents for the adsorption of Cs+ and Sr2+ is shown in Table 5 from the literature. However, a direct comparison of the adsorption capacity between the synthesized Aspergillus flavus used in this study and other adsorbents reported in the literature is challenging due to differences in experimental conditions applied in those studies. The maximum adsorption capacity for Cs+ and Sr2+ ions in our study was determined to be 26.6 and 211.1 mg g−1, respectively.

Conclusion

The dried biomass, Aspergillus flavus, functioned as an effective, environmentally friendly, and adsorbent for remediation aqueous solutions containing Cs+ and Sr2+ ions. This fungus biosorbent exhibits significant stability in aqueous environments, including exposure to acids, and bases, particularly at low concentrations, and possesses an irregular shape. It possesses commendable thermal stability. The fast adsorption of cesium and strontium, as demonstrated in the current biomass, is proposed to be significant as an effective biosorbent, allowing rapid sorption kinetics. The positive value of ΔH indicates the endothermic characteristic of the process. The measurement of ΔS indicated increased randomness at the adsorbate-adsorbent interface during the operation. The ΔH values are < 40 kJ/mol, indicating that the process was managed by physical biosorption. Upon treatment of the loaded biosorbent material with 0.1 M HNO3, all adsorbed metal ions were eluted, rendering the biosorbent devoid of any sorbed metal, thus enabling its efficient reuse for three cycles. The disposal of treated wastewater and biosorption sludge is a critical environmental consideration. While Aspergillus flavus biomass effectively removes Cs and Sr ions, the adsorbed radionuclides onto the used biomass materials must be managed in a later stage. To minimize environmental risks, the incineration of spent biomass, ensuring volume reduction, is conducted in licensed radioactive waste incineration, mitigating airborne releases through HEPA filtration, and remote handling and shielded storage are mandatory to comply with ALARA principles. The encapsulation or solidification methods can be employed for the resulting ash to stabilize the radioactive aqueous solution before disposal in designated waste storage facilities. Encapsulating the sludge and storing it in deep underground facilities designed for long-term containment of radioactive materials. Future studies should explore regeneration techniques for the fungal biomass to reduce waste generation and enhance cost-effectiveness, with details of safe handling of waste management.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

-

Attallah, M. F., Youssef, M. A. & Imam, D. M. Preparation of novel nano composite materials from biomass waste and their sorptive characteristics for certain radionuclides. Radiochim. Acta. 108, 137–149 (2020).

-

Attallah, M. F., Abdelbary, H. M., Elsofany, E. A., Mohamed, Y. T. & Abo-Aly, M. M. Radiation safety and environmental impact assessment of sludge TENORM waste produced from petroleum industry in Egypt. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 142, 308–316 (2020).

-

Borai, E., Hilal, M., Attallah, M. & Shehata, F. Improvement of radioactive liquid waste treatment efficiency by sequential cationic and anionic ion exchangers. Radiochim. Acta. 96, 441–447 (2008).

-

Youssef, M., El-Naggar, M., Ahmed, I. & Attallah, M. Batch kinetics of 134Cs and 152+154Eu radionuclides onto poly-condensed feldspar and perlite based sorbents. J. Hazard. Mater. 403, 123945 (2021).

-

Uzair, B., Shaukat, A., Fasim, F. & Maqbool, S. Conjugate Magnetic Nanoparticles and Microbial Remediation, a Genuine Technology To Remediate Radioactive Waste197–211 (Soil Microenvironment for Bioremediation and Polymer Production, 2019).

-

Yang, H. M. et al. Prussian blue-functionalized magnetic nanoclusters for the removal of radioactive cesium from water. J. Alloys Compd. 657, 387–393 (2016).

-

Emara, A. M., El-Sweify, F. H., Abo-Zahra, S. F., Hashim, A. I. & Siyam, T. E. Removal of Cs-137 and Sr-90 from reactor actual liquid waste samples using a new synthesized bionanocomposite-based carboxymethylcellulose. Radiochim. Acta. 107, 695–711 (2019).

-

Yu, R. et al. Behavior and mechanism of cesium biosorption from aqueous solution by living Synechococcus PCC7002. Microorganisms 8, 491 (2020).

-

Ayele, A., Haile, S., Alemu, D. & Kamaraj, M. Comparative utilization of dead and live fungal biomass for the removal of heavy metal: a concise review. The Scientific World J., 2021, 5588111. (2021).

-

Wu, J. et al. Efficient removal of Sr2+ and cs++ from aqueous solutions using a sulfonic acid-functionalized Zr-based metal–organic framework. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 328, 769–783 (2021).

-

Șenilă, M., Neag, E., Tănăselia, C. & Șenilă, L. Removal of cesium and strontium ions from aqueous solutions by thermally treated natural zeolite. Materials 16, 2965 (2023).

-

Bosco, F. & Mollea, C. Mycoremediation in soil. In Environmental chemistry and recent pollution control approaches, (IntechOpen). (2019).

-

Dotaniya, M. et al. Microbial assisted phytoremediation for heavy metal contaminated soils. Phytobiont Ecosyst. Restit., 295–317. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-1187-1_16 (2018).

-

Cecchin, I. et al. Integration of nanoparticles and bioremediation for sustainable remediation of chlorinated organic contaminants in soils. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegradation. 119, 419–428 (2017).

-

Malla, M. A. et al. Understanding and designing the strategies for the microbe-mediated remediation of environmental contaminants using omics approaches. Front. Microbiol. 9, 1132 (2018).

-

Cai, Y. H., Yang, X. J. & Schäfer, A. I. Removal of naturally occurring strontium by nanofiltration/reverse osmosis from groundwater. Membranes 10, 321 (2020).

-

Lim, W. R., Lee, C. H. & Lee, C. M. The removal of strontium ions from an aqueous solution using Na-A zeolites synthesized from Kaolin. Materials 17, 575 (2024).

-

Guo, J. et al. L.a. Rapid and effective removal of strontium ions from aqueous solutions by a novel layered metal sulfide NaTS-2. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 332, 2367–2378 (2023).

-

Carris, L. M., Little, C. R. & Stiles, C. M. Introduction to fungi. The plant health instructor, 48. (2012).

-

Mohmand, A. Q. K., Kousar, M. W., Zafar, H., Bukhari, K. T. & Khan, M. Z. Medical importance of fungi with special emphasis on mushrooms. ISRA Med. J. 3, 1–44 (2011).

-

Ghaed, S., Shirazi, E. K. & Marandi, R. Biosorption of copper ions by Bacillus and Aspergillus species. Adsorpt. Sci. Technol. 31, 869–890 (2013).

-

Teixeira, M. M. et al. Exploring the genomic diversity of black yeasts and relatives (Chaetothyriales, Ascomycota). Studies in mycology, 86, 1–28. (2017).

-

Javanbakht, V., Alavi, S. A. & Zilouei, H. Mechanisms of heavy metal removal using microorganisms as biosorbent. Water Sci. Technol. 69, 1775–1787 (2014).

-

da Ferreira, R., Vendruscolo, G. L. & Filho, A. F., and N.R. Biosorption of hexavalent chromium by Pleurotus ostreatus. Heliyon 5, (2019).

-

Karnwal, A. Unveiling the promise of biosorption for heavy metal removal from water sources. Desalination Water Treat., 319, 100523. (2024).

-

Kapoor, A. Removal of Heavy Metals from Aqueous Solution by fungi Aspergillus Niger (Faculty (of Graduate Studies and Research, University of Regina), 1998).

-

Thakkar, H. et al. 3D-printed zeolite monoliths for CO2 removal from enclosed environments. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 8, 27753–27761 (2016).

-

Ayangbenro, A. S. & Babalola, O. O. A new strategy for heavy metal polluted environments: a review of microbial biosorbents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 14, 94 (2017).

-

Cai, C. X. et al. A novel approach of utilization of the fungal conidia biomass to remove heavy metals from the aqueous solution through immobilization. Sci. Rep. 6, 36546 (2016).

-

Gadd, G. M. Biosorption: critical review of scientific rationale, environmental importance and significance for pollution treatment. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnology: Int. Res. Process. Environ. Clean. Technol. 84, 13–28 (2009).

-

Volesky, B. Detoxification of metal-bearing effluents: biosorption for the next century. Hydrometallurgy 59, 203–216 (2001).

-

Shekhawat, D., Jackson, J. E. & Miller, D. J. Process model and economic analysis of Itaconic acid production from dimethyl succinate and formaldehyde. Bioresour Technol. 97, 342–347 (2006).

-

Sumalatha, B. et al. A sustainable green approach for efficient capture of strontium from simulated radioactive wastewater using modified Biochar. Int. J. Environ. Res. 16, 75 (2022).

-

Dulla, J. B., Tamana, M. R., Boddu, S., Pulipati, K. & Srirama, K. Biosorption of copper (II) onto spent biomass of Gelidiella acerosa (brown marine algae): optimization and kinetic studies. Appl. Water Sci. 10, 56 (2020).

-

Khan, A. A. et al. Assessment of algal biomass towards removal of cr (VI) from tannery effluent: a sustainable approach. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29, 61856–61869 (2022).

-

Boddu, S., Dulla, J. B., Alugunulla, V. N. & Khan, A. A. An assessment on removal performance of arsenic with treated Turbinaria vulgaris as an adsorbent: characterization, optimization, isotherm, and kinetics study. Environ. Prog Sustain. Energy. 39, e13313 (2020).

-

Salama, O. utilization of bio fertilizers and organic sources in arable soils under saline conditions using tracer technique, (2011).

-

Czapek, F. Untersnehengen Uber die Stiekstoff gewinnung und Eriwesseikdung der Pflonzen Beitr. Chem. Physiol. U Pathol. 1, 540–560 (1902).

-

Metwally, S. & Attallah, M. Impact of surface modification of chabazite on the sorption of iodine and molybdenum radioisotopes from liquid phase. J. Mol. Liq. 290, 111237 (2019).

-

Ghoniemy, E. et al. Fungal treatment for liquid waste containing U (VI) and Th (IV). Biotechnol. Rep. 26, e00472 (2020).

-

Kang, B. et al. Thermal analysis for differentiating between oleaginous and non-oleaginous microorganisms. Biochem. Eng. J. 57, 23–29 (2011).

-

Iqbal, M. S., Massey, S., Akbar, J., Ashraf, C. M. & Masih, R. Thermal analysis of some natural polysaccharide materials by isoconversional method. Food Chem. 140, 178–182 (2013).

-

Arıca, M. Y., Arpa, C., Ergene, A., Bayramoğlu, G. & Genç, Ö. Ca-alginate as a support for Pb (II) and Zn (II) biosorption with immobilized phanerochaete Chrysosporium. Carbohydr. Polym. 52, 167–174 (2003).

-

Kapoor, A. & Viraraghavan, T. Heavy metal biosorption sites in Aspergillus Niger. Bioresour Technol. 61, 221–227 (1997).

-

Kapoor, A., Viraraghavan, T. & Cullimore, D. R. Removal of heavy metals using the fungus Aspergillus Niger. Bioresour Technol. 70, 95–104 (1999).

-

Fan, S., Jiang, L., Jia, Z., Yang, Y. & Hou L.a. Comparison of adsorbents for cesium and strontium in different solutions. Separations 10, 266 (2023).

-

Langmuir, I. The adsorption of gases on plane surfaces of glass, mica and platinum. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 40, 1361–1403 (1918).

-

Freundlich, H. M. F. Over the adsorption in solution. J. Phys. Chem. 57, 1100–1107 (1906).

-

Ghazy, O., Hamed, M. G., Breky, M. & Borai, E. H. Synthesis of magnetic nanoparticles-containing nanocomposite hydrogel and its potential application for simulated radioactive wastewater treatment. Colloids Surf., A. 621, 126613 (2021).

-

Breky, M. M. E., Abdel-Razek, A. S. & Sayed, M. S. Removal of some hazardous ions using titanium oxide and Cunninghamella elegans immobilized in alginate–carboxymethyl cellulose beads. Desalination Water Treat. 245, 116–128 (2022).

-

Rambabu, K., Bharath, G., Banat, F. & Show, P. L. Biosorption performance of date palm empty fruit bunch wastes for toxic hexavalent chromium removal. Environ. Res. 187, 109694 (2020).

-

Legorreta-Castañeda, A. J., Lucho-Constantino, C. A., Beltrán-Hernández, R. I., Coronel-Olivares, C. & Vázquez-Rodríguez, G. A. Biosorption of water pollutants by fungal pellets. Water 12, 1155 (2020).

-

Zhang, H., Yuan, X., Xiong, T., Wang, H. & Jiang, L. Bioremediation of co-contaminated soil with heavy metals and pesticides: influence factors, mechanisms and evaluation methods. Chem. Eng. J. 398, 125657 (2020).

-

Escudero, L. B., Quintas, P. Y., Wuilloud, R. G. & Dotto, G. L. Recent advances on elemental biosorption. Environ. Chem. Lett. 17, 409–427 (2019).

-

Li, D., Zhang, B. & Xuan, F. The sequestration of Sr (II) and Cs (I) from aqueous solutions by magnetic graphene oxides. J. Mol. Liq. 209, 508–514 (2015).

-

Abdel Maksoud, M., Murad, G., Zaher, W. & Hassan, H. Adsorption and separation of Cs (I) and Ba (II) from aqueous solution using zinc ferrite-humic acid nanocomposite. Sci. Rep. 13, 5856 (2023).

-

Attallah, M., Abd-Elhamid, A., Ahmed, I. & Aly, H. Possible use of synthesized nano silica functionalized by Prussian blue as sorbent for removal of certain radionuclides from liquid radioactive waste. J. Mol. Liq. 261, 379–386 (2018).

-

Abass, M. R., Kandeel, E. M., Abou-Lilah, R. A. & Mohamed, M. K. Effective biosorption of cesium and strontium ions from aqueous solutions using silica loaded with Aspergillus Brasiliensis. Water Air Soil. Pollut. 235, 61 (2024).

-

Dwivedi, C., Pathak, S. K., Kumar, M., Tripathi, S. C. & Bajaj, P. N. Preparation and characterization of potassium nickel hexacyanoferrate-loaded hydrogel beads for the removal of cesium ions. Environ. Science: Water Res. Technol. 1, 153–160 (2015).

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mousa, A.M., Breky, M.M. & Attallah, M.F. Biosorption of cesium and strontium from aqueous solution by Aspergillus flavus biomass. Sci Rep 15, 26328 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11603-9

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11603-9