Introduction

Fruit rot disease is a major concern in agriculture, causing significant pre- and post-harvest losses worldwide. Several fungi, such as Lasiodiplodia theobromae, Fusarium oxysporum, Fusarium proliferatum, and Colletotrichum gloeosporioides are known to cause rot by infecting various plant parts, such as stems, roots, flowers, leaves, and fruits, thereby threatening overall crop production1,2,3,4. While chemical fungicides are often used to control these pathogens, their extensive use has raised environmental and health issues such as residue accumulation, toxicity to non-target organisms, and the development of fungicide resistance5,6.

In response to these concerns, biopesticides have emerged as a safer and more environmentally sustainable alternative. Biopesticides, which are pest management agents derived from living microorganisms or natural products, are increasingly applied in agricultural settings due to their reduced toxicity, enviromental compatibility and specificity toward target pests, which help preserve beneficial organisms7,8. They are classified based on their sources of extraction and the nature of the active compounds involved7. Among various types, plant-based extracts and essential oils have gained increasing attention as natural pest control agents. These botanically derived products contain diverse bioactive compounds and exhibit multiple modes of action, including repellent, antifeedant, larvicidal, ovicidal, and growth-inhibitory effects. Their efficacy depends on the physiological traits of the target species and the phytochemical composition of the extract7,9,10.

Mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana Linn.), a tropical fruit widely cultivated in Southeast Asia, is a promising source of bioactive compounds. Its pericarp (peel) is rich in xanthones, flavonoids, terpenes, tannins, anthocyanins, and polyphenols. Several studies have reported that mangosteen peel extracts significantly inhibit the mycelial growth and spore germination of phytopathogenic fungi, including Fusarium oxysporum, Drechslera oryzae, and Alternaria tenuis11,12.

To enhance the performance of such hydrophobic bioactives, microemulsion were chosen as the formulation delivery system. Microemulsions offer high solubilization capacity of lipophilic compound, thermodynamic stability, and low-energy input for formation as compared to other nanocarrier systems13. Besides, their micrometric droplet size promotes better dispersion, improved penetration, and controlled release of active ingredients, leading to enhanced antifungal efficacy compared to conventional formulations.

In this study, we aimed to develop and optimize a microemulsion-based biopesticide incorporating ethanolic extracts of G. mangostana peel and evaluate its antifungal efficacy against selected fruit rot pathogens under both in vitro and in vivo conditions. This formulation offers a promising eco-friendly approach for managing fruit rot diseases and contributes to sustainable disease control strategies in agriculture.

Results

Solubility screening and microemulsion formulation

Solubility studies showed that virgin coconut oil (VCO) had the highest capacity to dissolve the crude ethanolic extract of G. mangostana peel, forming a clear and stable solution at concentrations up to 1.0% (w/v). In contrast, olive oil and palm oil produced multiple-phase separations. Consequently, VCO was used as the oil phase for microemulsion. Formulation 3 (F3) consisted of 0.20% (w/w) mangosteen peel extract, 4.80% VCO, 5.00% Tween 80, 1.00% α-tocopherol, and water to complete 100% (w/w) was selected as the most stable, which contributes to enhanced formulation stability (Table 1). The resulting microemulsion appeared stable with no signs of phase separation or creaming over 6 months of storage at room temperature (28 °C) and 39 °C, indicating good formulation stability.

The droplet size, polydispersity index (PDI), and zeta potential of the optimized microemulsion (ME-80%) were characterized using a Zetasizer Nano Series (Malvern Instruments, UK). The mean droplet size of the microemulsion was 303.9 ± 20.32 nm, with a PDI of 0.433 ± 0.024, indicating a moderately narrow and uniform size distribution. This may be attributed to the complex composition of mangosteen peel extract, which contains multiple phytochemicals that can influence interfacial properties and droplet organization. The zeta potential value was − 44.93 ± 1.79 mV, suggesting strong electrostatic repulsion between droplets and thus good physical stability of the formulation.

The negative zeta potential could be attributed to the ionization of surface-active components in the formulation, which contributes to droplet repulsion and prevents coalescence. Generally, microemulsions with zeta potential values greater than ± 30 mV is considered stable. Therefore, the high negative zeta potential observed here confirms that the formulated mangosteen peel microemulsion is electrostatically stable and suitable for prolonged storage and bioactivity evaluation.

In vitro antifungal activity

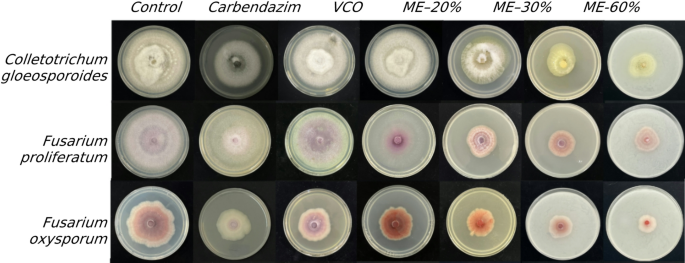

The microemulsion exhibited significant antifungal activity against all three tested pathogens. The microemulsion formulations demonstrated a clear dose-dependent inhibitory effect on the growth of C. gloeosporioides, F. oxysporum, and F. proliferatum, with higher concentrations exhibiting greater antagonistic activity. Across all tested pathogens, the microemulsion (ME) formulations, especially ME-80% and ME-60% are consistently outperform the commercial fungicide carbendazim. For C. gloeosporioides, ME-80% showed the highest inhibition (PIRG 76.92 ± 1.92%, very high activity), while ME-60% achieved moderate inhibition (59.64 ± 2.33%), both significantly surpassing carbendazim (33.03 ± 0.53%). Similar trends were observed for F. oxysporum, with ME-80% (60.43 ± 0.44%) and ME-60% (58.83 ± 0.76%) demonstrating moderate antagonistic activity (++) and clearly superior to carbendazim (10.49 ± 0.43%). In the case of F. proliferatum, both ME-80% (68.09 ± 2.28%) and ME-60% (67.78 ± 1.26%) exhibited high inhibition (+++), again markedly higher than carbendazim (42.19 ± 1.56%). Lower concentrations of ME and VCO showed significantly reduced activity but still generally exceeded the efficacy of carbendazim. These results collectively suggest that microemulsion formulations, particularly at concentrations of 60% and 80%, offer promising antifungal potential, surpassing the effectiveness of VCO and even the conventional fungicide carbendazim in some cases Table 2, Fig. 1.

Effect of different volumes of treatment (microemulsion) on mycelial growth of C. gloeosporoides, F. oxysporum, and F. proliferatum on PDA.

These results demonstrate a dose-dependent antifungal effect, with ME-80% exhibiting the highest efficacy. For C. gloeosporioides, the highest microemulsion concentration (18 mL or ME-80%) significantly reduced spore germination to 12.97 ± 0.23% and achieved the greatest inhibition rate of 48.33%, surpassing the chemical fungicide carbendazim, which recorded 40.00% inhibition (Table 3). As the concentration of the microemulsion decreased, spore germination increased correspondingly. ME-60% maintained moderate inhibition at 38.40%, while ME-20% and ME-30% showed substantially lower efficacy. A similar trend was observed for F. oxysporum, where ME-80% resulted in 42.93 ± 2.65% inhibition of spore germination, which is more than double the inhibition achieved by carbendazim (18.93 ± 0.15%). Although lower concentrations of the microemulsion exhibited reduced activity, they remained more effective than VCO and the untreated control, both of which showed no inhibitory effect.

In Vivo Efficacy on Fruits

Treatment of artificially infected fruits with ME-80% significantly reduced lesion development compared to untreated controls and was more effective than the commercial fungicide carbendazim (0.1%). In tomato, carbendazim treatment offered a moderate improvement, with a disease severity reduction of 10.79% (Table 4). For mango, carbendazim treatment resulted in a 37.63% reduction in anthracnose disease severity, demonstrating its ability to mitigate the impact of fungal infections. The microemulsion (ME-80%) treatment shows a high percentage, 75.92% reduction in disease severity. The reduction in disease severity demonstrates the formulation’s ability to inhibit pathogen proliferation under realistic conditions, highlighting its practical potential for postharvest disease control.

Data marked with different letters in each column indicates a statistically significant difference among of three treatments, replications, and the control for each fungal phytopathogen of lesion size and disease severity reduction (p < 0.05) based on Tukey’s HSD test. All fruits were incubated at room temperature (28 ± 2 °C).

The application of microemulsion (ME-80%) showed significant effects on the postharvest quality parameters of banana, tomato, and mango fruits when compared to untreated controls and carbendazim-treated samples (Table 5; Fig. 2).

Effects of microemulsion (ME-80%) containing G. mangostana pericarp crude extract on the reduction of fruit rot disease severity of banana, tomato, and mango compared to control and fungicide carbendazim inoculated with fungal species pathogens after treatment.

Additionally, peel color analysis revealed a lower color difference (ΔE* = 34.87) in ME-80% treated fruits, indicating delayed ripening or reduced color change, which was slightly more effective than carbendazim (ΔE* = 39.35). For tomatoes, ME-80% treatment significantly enhanced fruit firmness (4.90 N/cm²), outperforming both the control and carbendazim (3.00 and 3.23 N/cm², respectively). However, the sweetness of tomatoes was reduced to 2.30% (ME-80%) compared to control (3.43%) and carbendazim (3.13%), suggesting that the treatment may delay ripening or interfere with sugar accumulation. The peel color of tomatoes also changed more slowly in ME-80% treated fruits, with the lowest ΔE* value (46.05), indicating less progression toward the red ripe stage compared to carbendazim (51.26) and the control.

Similar trends were observed in mangoes, where ME-80% treatment resulted in significantly higher firmness (3.78 N/cm²) than the negative control (2.30 N/cm²) and was comparable to carbendazim (3.41 N/cm²). In terms of sweetness, the ME-80% treatment yielded the lowest value (2.58%), which was significantly lower than both control (5.07%) and carbendazim (4.29%), highlighting the potential of the microemulsion to modulate ripening-related sugar accumulation. The color difference values further confirmed this ripening delay, as ME-80% treated mangoes exhibited the lowest ΔE* (40.68), indicating less pronounced color transformation compared to the control (48.08) and carbendazim (44.19). Overall, these findings suggest that microemulsion containing G. mangostana pericarp extract at high concentrations effectively delays ripening, maintains fruit firmness, and alter peel coloration, making it a promising alternative to synthetic fungicides for postharvest treatment.

Mechanism and potential application

The enhanced performance of the microemulsion formulation may be attributed to the synergistic interaction between the phytochemicals and the micro-sized emulsion droplets, which facilitate better penetration and uniform distribution over the fruit surface. Tween 80 acts as a surfactant that improves the solubility of hydrophobic compounds, while α-tocopherol helps stabilize the formulation and prevent oxidative degradation of active components. These factors collectively enhance the antifungal efficacy of the extract, making microemulsion a promising alternative to synthetic fungicides.

Overall, the findings support the development of mangosteen-based microemulsions as effective, eco-friendly biopesticides for the control of fruit rot pathogens. The formulation’s efficacy in both in vitro and in vivo assays suggest its potential for commercial development, especially in organic and low-input farming systems where chemical pesticide use is restricted.

Discussion

This study highlights the potential of a mangosteen peel-based microemulsion as an effective biopesticide for controlling fruit rot pathogens, including F. oxysporum, F. proliferatum, and C. gloeosporioides. The optimized formulation, comprising VCO, Tween 80, and α-tocopherol, demonstrated strong antifungal activity across all assays. The ME-80% formulation consistently outperformed lower concentrations and surpassed the chemical fungicide carbendazim in suppressing mycelial growth and spore germination. The observed antifungal activity can be attributed to the bioactive compounds present in G. mangostana peel extract, particularly xanthones and flavonoids. These phytochemicals have been shown to disrupt fungal cell membranes, inhibit spore germination, and interfere with mitochondrial function14. Consistent with earlier studies, the present findings reinforce the antifungal potential of mangosteen-derived compounds, especially against Fusarium and Colletotrichum species, the important postharvest pathogens in tropical agriculture.

Previous research has shown that xanthones not only possess antifungal activity but also exhibit antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, which may help protect fruit tissue from pathogen-induced oxidative stress15,16,17. Furthermore, the microemulsion system enhances the solubility, stability, and bioavailability of these compounds, thereby improving their efficacy under both in vitro and in vivo conditions.

The antifungal effects were dose-dependent, with higher concentrations leading to greater inhibition. ME-80% significantly reduced spore germination of C. gloeosporioides and achieved a greater inhibition rate, compared to carbendazim. A similar trend was observed for F. oxysporum. These findings align with previous reports on the antimicrobial properties of xanthone derivatives18,19.

The superior performance of microemulsion can be attributed to its nanoscale structure, which improves the dispersion and penetration of hydrophobic compounds into fungal cells20. Tween 80, a non-ionic surfactant, stabilizes the oil-water interface, while α-tocopherol protects the active compounds from oxidation. This formulation approach supports prior findings on the effectiveness of microemulsions for delivering botanical pesticides21,22.

In vivo assays further validated the efficacy of ME-80%, with treated fruits showing significantly smaller lesions than untreated controls and those treated with carbendazim. These results suggest that formulation not only inhibits pathogen development but also reduces postharvest decay, potentially extending the shelf life of treated fruits. The enhanced performance over carbendazim may reflect the multi-targeted action of plant-based compounds, which also lowers the risk of resistance development.

The use of mangosteen peel as a raw material supports sustainable agriculture and waste valorization. Often discarded as waste, the pericarp is rich in pharmacologically active compounds. By incorporating this agro-waste into a microemulsion biopesticide, the study promotes a circular bio-economy model that adds value to agricultural residues while minimizing reliance on synthetic chemicals.

Despite the promising outcomes, further research is required to evaluate the field performance of the formulation under diverse environmental conditions and during long-term storage. Although this study focused on identification and pathogenicity assessment, mechanistic evidence such as microscopic observation was not included. Future studies should address this aspect to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the infection mechanisms. Additionally, detailed ecotoxicological evaluations, risk assessments, identification of key bioactive components, and evaluation of sensory effects in fruit applications are essential to ensure the safe integration of this product into commercial pest management practices.

Materials and methods

Plant material and preparation of extract

Fresh mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.) fruits were collected from a local farm in Serdang, Selangor. The peels were separated, thoroughly washed with distilled water, and air-dried at room temperature. The dried peels were then ground into a fine powder using a mechanical grinder. Approximately 30 g of the powdered sample was mixed with 300 ml of 99% ethanol and hexane, respectively. The mixtures were shaken for 24 h at 150 rpm and 28 ± 2 °C in an incubator shaker23. The resulting extracts were filtered through Whatman No. 1 filter paper and concentrated under reduced pressure using a rotary evaporator at 40 °C to obtain the crude ethanolic extract.

Solubility and oil phase screening

To determine the most suitable oil phase for microemulsion formulation, solubility tests were conducted using three types of oils: virgin coconut oil (VCO), olive oil, and palm oil. The solubility of the mangosteen peel extract in each oil was tested by gradually increasing the concentration of extract up to 1.0% (w/v). Based on visual clarity and phase stability, VCO was selected as the optimal oil phase.

Microemulsion formulation

Microemulsions were formulated using the phase inversion composition (PIC) method. The phase behavior of the VCO/Tween 80/water system was examined using three formulations (F1, F2, and F3), each containing up to 0.2% of the G. mangostana crude extract to ensure stability and homogeneity. To prevent lipid peroxidation, 1% α-tocopherol was added to the oil phase, and the resulting mixture was subjected to magnetic stirring using a FAVORIT magnetic stirrer at a speed of 600 rpm for 15 min. Following the preparation of the oil phase, Tween 80 was introduced into the mixture at a concentration of 4.00–5.00% by weight. The mixture was continuously homogenized to ensure uniform dispersion. Subsequently, water, constituting 85.00–95.00% of the total weight, was gradually incorporated into the system. The aqueous phase was added slowly and continuously while stirring, ensuring proper integration and stability of the microemulsion. The final emulsion underwent continuous stirring at a speed of 800 rpm for a total duration of two hours to achieve optimal dispersion and stability. The method facilitated the efficient formation of a microemulsion system with desirable physicochemical properties24,25. The mixture was stirred continuously at room temperature until a stable and homogenous oil-in-water (O/W) microemulsion was formed. The formulations were stored at 4 °C prior to further analysis.

Physicochemical characterization

The selected formulation consisted of 0.20% (w/w) mangosteen peel extract, 4.80% VCO as the oil phase, 5.00% Tween 80 as the surfactant, 1.00% α-tocopherol as an antioxidant, and distilled water to make up the balance to 100% (w/w) was further analyzed for particle size. The mean particle size, PDI, and zetapotential of emulsion formulations were measured using Zetasizer (Nano ZS90, Malvern Instruments, UK), fitted with an argon laser (λ = 488 nm) at a scattering angle of 173°. The sample was gradually loaded to full (~ 1.5 mL) in a folded capillary cell to prevent the formation of air bubbles before being inserted into the sample chamber. Measurements were carried out at controlled room temperature (25 ± 1 °C) after equilibrated for 120 s to stabilize the cell area temperature. Each sample was measured three times, and the data were expressed as the mean.

Stability testing of microemulsion

The stability of a microemulsion was tested using two primary methods: centrifugation and storage at various temperatures for 7 days to 6 months. Centrifugation is a widely accepted method for assessing the physical stability of colloidal systems, including microemulsions. By subjecting the microemulsion to a high rotational speed, this test accelerates the potential separation process, mimicking long-term storage conditions in a short time frame.

All formulations were subjected to centrifugation and physical observation. All formulations were centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 15 min, followed by storage tests at 4 °C, 28 °C (room temperature), 39 °C, and 50 °C for durations of 7 days, 1 month, 3 months, and 6 months. After each cycle, observations were made to detect any signs of instability, such as the formation of distinct layers, precipitation of active components, or changes in opacity and color. The absence of phase separation after centrifugation would indicate that the microemulsion possesses strong kinetic stability, while the presence of separation would suggest the need for further formulation optimization.

Test fungal pathogens

Three phytopathogenic fungi, Fusarium oxysporum, Fusarium proliferatum, and Colletotrichum gloeosporioides were used in this study. The fungal isolates were obtained from the fungal culture collection, Laboratory of Mycology, Department of Biology, UPM. The isolates were originally obtained from fruit-rot-infected fruits and identified based on morphological and molecular characterization. The pathogenicity test confirmed that all isolates could cause fruit rot on banana, mango, and tomato. Cultures were maintained on potato dextrose agar (PDA) at 28 ± 2 °C.

In vitro antifungal assay

The microemulsion formulation was sterilized using Whatman Quantitative Filter Paper membranes (0.22 μm) to ensure the removal of any microbial contaminants. Each pathogen was cultured on PDA amended with different concentrations of microemulsion (20%, 30%, 60%, and 80%). Control plates were prepared in two forms: one without the microemulsion extract and another containing 0.8 mL of VCO mixed with 19.2 mL of PDA to account for the potential impact of the emulsifying agent. The antifungal efficacy of the microemulsion was tested against fungal pathogens using a seven-day-old mycelial disc (6 mm diameter) placed at the center of each poison agar plate. The plates were then incubated at room temperature (28 ± 2 °C) for eight days. Fungal growth was monitored daily, and the inhibition rate was measured by comparing colony diameters between treated and untreated plates.

Spore germination assay

Spore suspensions (1 × 10⁶ spores/mL) of each pathogen were prepared in sterile distilled water. Drops of the suspension were mixed with an equal volume of the microemulsion and incubated in a moist chamber at 25 °C for 24 h. Spores were stained with lactophenol cotton blue and observed under a light microscope. The percentage of germinated spores was recorded by counting at least 100 spores per replicate.

In vivo efficacy on fruits

Banana, tomato, and mango fruits were artificially inoculated with the three fungal pathogens and treated with ME-80%, carbendazim (a chemical fungicide as a positive control, 0.1% w/v, commercial formulation, Bayer CropScience), and sterile water (negative control). The in vivo antifungal evaluation was conducted using the wound method by inoculating a fungal mycelial plug onto each treated fruit. The inoculated fruits were placed in plastic containers with lids and incubated at room temperature (28 ± 2 °C) under ~ 95% relative humidity for seven days. The experimental design followed a completely randomized block arrangement. Each treatment consisted of three biological replicates with five fruits per replicate, and each measurement was repeated three times. The antifungal evaluation of the microemulsion-treated fruits provided insights into their effectiveness in preventing fruit rot disease and maintaining fruit quality. The flesh firmness was measured using a fruit penetrometer (Model GY Series, Hangzhou Yuefeng Instrument Co., Ltd., China) equipped with a 5 mm diameter plunger. The analysis indicated that treated fruits retained higher firmness values compared to the control, suggesting that the microemulsion helped maintain cellular integrity and reduce fungal degradation. Similarly, the °Brix values revealed that treated fruits exhibited higher sugar retention, potentially due to reduced fungal-induced metabolic changes. Colour measurements showed that the treated fruits maintained a more uniform colour profile with lower ΔE* values, indicating lesser degradation and discoloration.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 22.0 (IBM Corp., USA) with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) using Tukey’s test with significance set at p < 0.05. Normality and homogeneity of variances were verified before performing ANOVA.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

-

Jabnoun-Khiareddine, H., Ben Abdallah, R. A., Mars, M. & Daami-Remadi, M. Lasiodiplodia theobromae, Pestalotiopsis clavispora and Fusarium spp. Associated with pomegranate dieback and fruit rot in Tunisia. Crop Prot. 197, 107310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cropro.2025.107310 (2025).

-

Naseri, B. & Mousavi, S. S. Root rot pathogens in field soil, roots and seeds in relation to common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris), disease and seed production. Int. J. Pest Manage. 61 (1), 60–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/09670874.2014.984243 (2015).

-

Zainudin, N. A. I. M., Azahar, N., Rusli, M. N. H. & Md Nordin, N. A. Identification and characterization of fungi associated with leaf spot disease of rubber trees (Hevea brasiliensis) in Pahang, Malaysia. J. Plant. Prot. 7 (2), 89–102 (2023).

-

Zakaria, L. Fusarium species associated with diseases of major tropical fruit crops. Horticulturae 9 (3), 322. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae9030322 (2023).

-

Garud, A., Pawar, S., Patil, M. S., Kale, S. R. & Patil, S. A scientific review of pesticides: Classification, toxicity, health effects, sustainability, and environmental impact. Cureus 16 (8), e67945. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.67945 (2024).

-

Islam, T., Danishuddin, Tamanna, N. T., Matin, M. N., Barai, H. R. & Haque, M. A. Resistance mechanisms of plant pathogenic fungi to fungicide, environmental impacts of fungicides, and sustainable solutions. Plants 13 (19), 2737. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants13192737 (2024).

-

Ayilara, M. S. et al. Biopesticides as a promising alternative to synthetic pesticides: A case for microbial pesticides, phytopesticides, and nanobiopesticides. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1040901. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2023.1040901 (2023).

-

Khursheed, A. et al. Plant-based natural products as potential ecofriendly and safer biopesticides: A comprehensive overview of their advantages over conventional pesticides, limitations and regulatory aspects. Microb. Pathog. 173 (Part A), 105854. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2022.105854 (2022).

-

Magierowicz, K., Górska-Drabik, E. & Golan, K. Effects of plant extracts and essential oils on the behavior of Acrobasis advenella (Zinck.) caterpillars and females. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 127, 63–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41348-019-00273-5 (2020).

-

Shaari, F. N. & Mohd Zainudin, N. A. I. In vitro and in vivo assays of selected plant extracts against fruit rot fungi. Sains Malaysiana. 52 (9), 2545–2557 (2023).

-

Murad, N. B. A., Mustafa, M., Shaari, K. & Zainudin, N. A. I. M. Antifungal activity of aqueous plant extracts and effect on morphological and germination of fusarium fruit rot pathogens. Sains Malaysiana. 50 (6), 1589–1598. https://doi.org/10.17576/jsm-2021-5006-07 (2021).

-

Yahya, N. N., Zawawi, N. & Ahmad, R. Effect of mangosteen Peel extract on spore germination of plant pathogens. J. Nat. Prod. Res. 12 (3), 115–123 (2020).

-

Suhail, N. et al. Microemulsions: unique properties, Pharmacological applications, and targeted drug delivery. Front. Nanatechnol. 3, 754889 (2021).

-

Murad, N. B. A., Mustafa, M., Shaari, K. & Mohd Zainudin, N. A. I. Micrograph analysis of morphological alteration and cellular damage of fruit rot fungal pathogens treated with Averrhoa bilimbi fruit and Garcinia Mangostana pericarp ethanolic extracts. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 75 (5), 1319–1329. https://doi.org/10.1111/lam.13801 (2022).

-

Feng, Z., Lu, X., Gan, L., Zhang, Q. & Lin, L. Xanthones, a promising anti-inflammatory scaffold: Structure, activity, and drug likeness analysis. Molecules 25 (3), 598. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25030598 (2020).

-

Oriola, A. O. & Kar, P. Naturally occurring Xanthones and their biological implications. Molecules 29 (17), 4241. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29174241 (2024).

-

Shan, T. et al. Xanthones from mangosteen extracts as natural chemopreventive agents: potential anticancer drugs. Curr. Mol. Med. 11 (8), 666–677 (2011).

-

Haizhou, L. et al. Development of Xanthone derivatives as effective broad-spectrum antimicrobials: disrupting cell wall and inhibiting DNA synthesis. Sci. Adv. 11, eadt4723. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adt4723 (2025).

-

Liu, X., Shen, J. & Zhu, K. Antibacterial activities of plant-derived Xanthones. RSC Med. Chem. 13 (2), 107–116. https://doi.org/10.1039/d1md00351h (2021).

-

Ramos, A. P., Zheng, Y., Peng, Y. & Ridruejo, A. Structure, partitioning, and transport behavior of microemulsion electrolytes: molecular dynamics and electrochemical study. J. Mol. Liq. 380, 121779 (2023).

-

Sarmah, K. et al. Innovative formulation strategies for botanical- and essential oil-based insecticides. J. Pest Sci. 98, 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10340-024-01846-2 (2025).

-

Sharma, A., Dubey, S. & Iqbal, N. Microemulsion formulation of botanical oils as an efficient tool to provide sustainable agricultural pest management. IntechOpen https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.91788 (2021).

-

Touba, E. P., Zakaria, M. & Tahereh, E. Antifungal activity of cold and hot water extracts of spices against fungal pathogens of roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa) in vitro. Microb. Pathog. 52, 125–129 (2012).

-

Mushtaq, A. et al. Recent insights into nanoemulsions: their preparation, properties, and applications. Food Chem. X. 18, 100684 (2023).

-

Wuttikul, K. & Sainakham, M. In vitro bioactivities and Preparation of nanoemulsion from coconut oil loaded curcuma aromatica extracts for cosmeceutical delivery systems. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 29 (12), 103435 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We would like to extend our sincere appreciation to the Universiti Driven Research Programme (UDRP) – Biodiversity and Conservation for their continuous support and encouragement.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zainudin, N.A.I.M., Azmi, N.H.M., Rahman, M.B.A. et al. Bioefficacy of a microemulsified mangosteen peel extract formulation against fruit rot fungi. Sci Rep 16, 4336 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33320-z

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

Version of record:

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33320-z