Introduction

Recent developments of sensors using biological components have provided new insight into physiology and made considerable contributions to therapy1. In most instances either biomolecules or clonal cell lines were used for specific analyte recognition2 and only in the case of an electronic tongue a micro-organ was used3. Continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) via an enzyme and electrochemical detection has considerably advanced therapy in type 1 diabetes4,5, the less common but most severe form of diabetes6. Pancreatic islets are at the center of nutritional homeostasis and their demise cause the most common metabolic disease characterized by increased blood glucose7,8,9. Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune disease characterized by a large or complete loss of islet β-cells and requires hormone replacement therapy10. As insulin, like most peptide hormones, exerts powerful action in the picomolar range, its concentration has to be carefully titrated to achieve therapeutic levels and avoid life-threatening hypoglycemia. This has led to the concept of a CGM-based artificial pancreas as a closed-loop system where a subcutaneous sensor measures glucose in the interstitial fluid and commands a small insulin injecting pump as an actuator via appropriate algorithms11. Despite the progress achieved during the last 50 years, the system still requires announcements of meals or physical activity and can provoke hypoglycemia4,5,12.

Within the islet micro-organ, the insulin-containing β-cells function as an actuator, which secrete insulin, the only glucose-lowering hormone. β-cells function also as sensors, which measure the amount of nutrients available in the blood and thus turn food into a command for insulin release. An increase in ambient nutrient levels leads to an increase in β-cell metabolism and ATP/ADP ratios, closure of ATP-dependent KATP channels, membrane depolarization, opening of voltage-dependent calcium channels, and calcium influx. Thus, metabolism of glucose and other nutrients induces changes in transmembrane ion fluxes and consequently in field potentials13. The calcium influx via different voltage-dependent ion channels induces highly regulated insulin release. Ion channel activities are further influenced by hormones, e.g., the stress hormone adrenalin or enteric peptide hormones14. Thus, transmembrane ion fluxes provide an integrative read-out according to the nutritional status and the state of the entire organism. Since pancreatic islets have undergone at least half a billion years of evolution15,16, they should provide a fairly optimal sensor. The β-cell read-out in terms of electrical activity and insulin secretion is considerably modulated by the other cell types present in the micro-organ, mainly α- and δ-cells17,18, which stimulate or inhibit, depending on the physiological situation. Such kind of interactions are predicted to provide stability and reduce sensor errors19,20. Moreover, in terms of activity islets react stronger to a decrease in glucose than to an increase, thus a hysteretic response. This response encoded by endogenous islet algorithms via their electrical activity provides a clinical safety mechanism against hypoglycemia21,22. Consequently, the overall electrical activity reflects a read-out shaped by multicellular sensing and forward as well as feedback loops.

The use of these micro-organs and their endogenous algorithms as a biosensor, instead of a single biomolecule or cells and complex synthetic algorithms, could thus offer considerable advantages. The label-free capture of electrical cellular signals as signatures of activity offers a number of gains as compared to other approaches. Gene transfer or chemical probes are not required for signal detection and the electronics dedicated to online signal analysis are well-suited for miniaturization23,24. We have previously studied and analyzed in detail the electrical responses of human and rodent islets in vitro using extracellular electrophysiology with microelectrode arrays (MEA)23,25,26,27,28,29,30,31. This non-invasive method allows recording over long time periods22,29,32,33 and even up to 8 days26. MEAs record changes in field potentials and the so-called slow potentials (SP) are summation signals generated by coordinated β-cell coupling, a hallmark of islet activation. Whereas frequencies reflect the rate of coupled events, amplitudes are correlated to the extent of physiological β-cell coupling29. In β-cells, the main ionic current is caused by Ca2+ fluxes34 and signals recorded by MEAs are closely linked to insulin secretion driven by calcium influx29. Moreover, electrical signatures of islet activity as recorded by MEAs, can be introduced in a simulator of human metabolism in T1D patients, called UVA/Padova35. This computer model simulates the glucose-insulin dynamics in T1D patients, and is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as an alternative for pre-clinical testing of insulin therapies, including closed-loop algorithms. Within this in silico model, an islet biosensor-based artificial pancreas was at least as efficient as standard CGMs and even outperformed them under challenging conditions36,37.

We therefore asked whether monitoring the electrical activity of a few islets may provide a sensor for continuous glucose measurements in live animals. To this end we developed stepwise microfluidic micro-electrode arrays containing a few islets and subsequently interfaced them with the interstitial fluid via microdialysis. Our data and their analysis indicate faithful monitoring of glucose levels via microdialysis and an extra-corpore microfluidic MEA in rats during glucose tolerance tests and subsequent to insulin injections.

Results

Design of the ex-corpore organ-based sensor

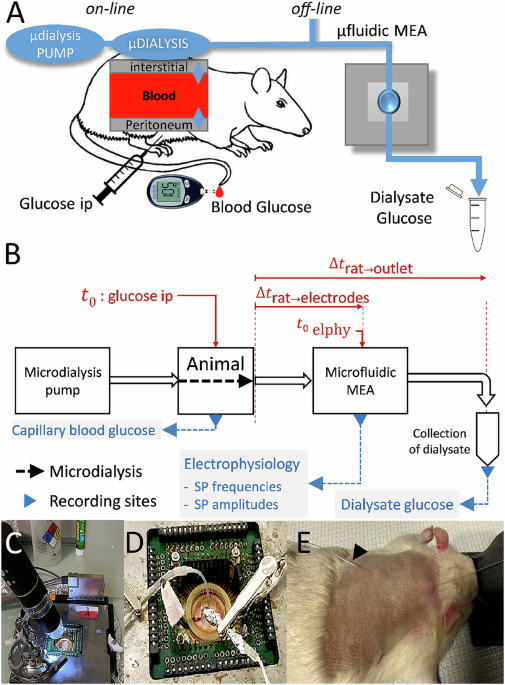

A biosensor using heterologous live cells, such as pancreatic islets, has to be conceived as an extracorporeal device and microdialysis can provide continuous access to bodily fluids such as interstitial liquids. As the amount of interstitial fluid that can continuously be retrieved is limited, miniaturization is required. To test an islet-based biosensor for continuous nutrient monitoring, interfacing of the animal with the sensor was developed as given in Fig. 1. Interstitial fluid is obtained via a microdialysis pump and a subcutaneous microdialysis catheter which is linked to a chip consisting of the sensor, a MEA with islets attached to its electrodes and the microfluidic system to pass the dialysate to these islets (Fig. 1A). The flow rate and thus microdialysis rate is governed by the delivery rate of the dialysis fluid38. To assess the biosensors’ characteristics, recordings have to be compared with blood glucose, which can be measured after small incisions at the rat’s tail vein and dialysate was also sampled after passage through the chip to determine its glucose concentration. This configuration has to deal with a number of delays between blood glucose and the sensor. First, diffusion of glucose in the interstitial space requires some 10 minutes in man39 and rat40. Second, in this laboratory set-up a certain length of tubing is required to link the components introducing additional delays between the point of dialysis and the microfluidic MEA (µMEA) as well from the µMEA to the point of glucose measuring in the dialysate at the outlet (Fig. 1B). We have tested these delays using phenol red as dye in the fluids and corrections for the resulting delay time (Fig. 1B, see also “Methods”) was used throughout when comparing different parameters on a time scale. Figure 1C–E shows the actual set-up on the bench with a video-microscope to observe potential formation of bubbles in the microfluidic channels (Fig. 1C), the microfluidic MEA (Fig. 1D) a rat with an implanted interscapular catheter for microdialysis (Fig. 1D).

A Anaesthetized rats were subjected to an intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test and blood glucose was determined. In off-line experiments, serum samples were added directly to the microfluidic MEA; in on-line experiments, interstitial fluids were dialyzed at 1 µl/min and fed to the microfluidic MEA. Glucose concentrations in the dialysate were determined off-line from an outflow channel of the microfluidic MEA. B Full set-up and work flow for on-line experiments. Time points in the experiment and delays introduced by tubings between microdialysis and the different recording sites are given. Δtrat-electrodes was 750 s, Δtrat-outlet (collection of dialysates) was 2460 s as determined by video films using a dye (see “Methods”). C MEA setup with microscope video camera to inspect flow. D Enlarged view of the MEA itself and microfluidic inlet/outlet. E Anesthetized rat with dorsal subcutaneous catheter inserted, arrows at inlet and outlet of subcutaneous dialysis.

Ex vivo monitoring of serum glucose and characterization of subcutaneous microdialysis

The final device was interfaced gradually. Previous work had used defined electrophysiological buffers and revealed the presence of two different electrical islet cell signals that can be recorded by extracellular electrophysiology. Whereas single-cell action potentials are difficult to capture due to their minute amplitude, robust SP are generated by cell-to-cell coupling. The SP amplitude depends on the degree of coupling between β-cells, which is a hallmark of physiological islet function22,41.

As islets on MEA had never been challenged with sera, we first tested the response to human or rat serum containing different glucose concentrations. We did so in static incubation in MEAs with home-made PDMS microwells to allow assaying of only a few microliters of analyte. As shown in Fig. 2A, B, E, islets exhibit strong responses in terms of SP frequency and amplitude in the presence of culture medium containing 11 mM glucose and amino acids. Replacing medium by human serum (6 mM glucose) induces a rapid decrease in electrical responses, which was subsequently increased by sequential exposure to human serum containing 9, 12 or 15 mM glucose. Statistical evaluation of the corresponding areas under the curve (AUCs) revealed significant differences in activity between all the glucose ramps from 6 to 15 mM (Fig. 2C, F) and a high degree of correlation between glucose concentrations in human serum and recorded responses (Fig. 2D, G), which suggested a good discrimination power of the biosensor. In a next step, we performed an intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test in a rat with a basal glucose level of 9.4 mM. Injection of 2 mg/kg of glucose led to a transient increase in blood glucose (Fig. 2H) to 22.9 mM followed by a slow decrease to 11.9 and 8.6 mM. At each determination of blood glucose, sera were prepared and added ex tempore to PDMS microwells fixed on MEAs for off-line determination of electrical activity (Fig. 2 I, K). The change from 9.4 to 22.9 mM glucose induced a strong response in the biosensor in terms of SP frequency and amplitude. Responses were clearly distinct among the conditions and were all significantly different for SP frequencies and also for SP amplitudes except for G12 vs G9 in the latter case (Fig. 2, J, L). This validated that the islet-based biosensor can be used with serum and provides discrimination between glucose levels differing by a few millimoles/liter.

A Solutions used; CM, culture medium containing amino acids and 11 mM glucose; G6, human serum containing 6 mM glucose; G9 to G15, same human serum adjusted to 9, 12 or 15 mM glucose; G0, buffer without glucose; G0, 0 Ca2+, buffer without glucose and calcium. B Frequencies of slow potentials recorded by microwell MEAs under the different conditions given in (A). C Areas under the curve from B determined during the first 10 min of each stimulus and expressed as AUC/minute. D Pearson correlation analysis of C (SP frequency vs. glucose concentrations). E Amplitudes of slow potentials recorded by microwell MEAs under the different conditions given in (A). F Areas under the curve from E determined during the first 10 min of each stimulus and expressed as AUC/minute. G Pearson correlation analysis of C (SP amplitude vs. glucose concentrations). H Intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test in an anaesthetized rat. Blood samples were collected at indicated time points, corresponding sera prepared and glucose concentrations determined. I Effect of rat sera in on slow potential frequencies in microwell MEAs. Glucose concentrations in the sera are given on top. J Statistical analysis of AUCs determined as in (I). K Effect of rat sera on slow potential amplitudes during same recordings as in (G). L Statistical analysis of AUCs determined as in (C). Means and SEM are indicated in full colors and corresponding shades, respectively, in (B, I, E, K). *, 2p < 0.05; ***, 2p < 0.001; ****, 2p < 0.0001 as compared to the presence of different glucose concentration. ANOVA and paired Tukey post-hoc tests, n as given in the corresponding panels, N (different animals), 2–3.

We subsequently tested rat microdialysis dialysate off-line with the MEA biosensor (Fig. 3). Blood glucose recovery by dialysis at a fixed glucose level depended on flow rates (Fig. 3A). The rate of 1 µl/min provided sufficient glucose recovery from a test sample (Fig. 3A) and a reasonable flow. This setting was chosen for all subsequent experiments and provided a constant recovery at about 78% at low and high glucose levels during a glucose tolerance test in rat (Fig. 3B). Next, we tested the two dialysates obtained in rat before (t = 0, G5.8) and during the glucose tolerance test (t = 30, G15) in the biosensor. We observed a strong increase in activity when changing from 5.8 (t = 0) to 15 mM (t = 30) dialysate glucose in terms of frequencies (Fig. 3C, D) and of amplitudes (Fig. 3E, F). Islets are physiological activated in a strong, short-lasting first and lesser but long-lasting second phase of insulin secretion42. Notably, the physiological first and second phase of islet activation were visible, especially in terms of electrical frequencies and amplitudes (Fig. 3C, E), which is due to differences in coupling during islet β-cell activation29.

A Recovery rates for glucose in saline buffer at different flow rates per minute (0.3–2 µl/min). B Glucose concentrations in rat capillary blood and in dialysate (flow rate 1 µl/min) after intraperitoneal injection of glucose (ip) and recovery rates C Effect of corresponding dialysates (at 5.8 and 15 mM glucose; G5.8, G15) on islet slow potential frequencies. Blue dotted line indicates 1st vs 2nd phase. D Statistics of areas under the curve (G 5.8, 0–14 min; G15 1st phase 14–18 min; G15 2nd phase 20–43 min; G15 14–43 min; expressed as AUC/min). E Effect of corresponding dialysates (at 5.8 or 15 mM glucose) on islet slow potential amplitudes. D Statistics of areas under the curve (details see D). **, 2p < 0.01; ****, 2p < 0.0001 (Tukey post-hoc test), n = 12. All data are given as mean ± SEM.

Characterization of microfluidic micro-electrode arrays and in vivo monitoring of glucose concentrations

We initially explored chip configurations allowing single islet trapping on metal electrodes to accommodate the small flow rates of microdialysis. Although such a set-up worked satisfactorily in vitro, this was not the case when interfacing this with microdialysis and a live animal due to recurrent bubble formation despite all diligence and bubble traps. Moreover, islets are known to be heterogeneous in size and relative occurrence of the different endocrine cell types43. Therefore, recording from a number of islets and not just single islets provides a more physiological readout. We therefore opted for a simpler and more robust approach (Fig. 4A–C) consisting of a PDMS block with a single channel, inlet and outlet (Fig. 4A) that was aligned on half of the 60 electrodes of a commercial MEAs in a cleanroom under a binocular microscope as shown in Fig. 4B. The microfluidic channel is charged with about 40 islets that cover about 10–15 of the 30 electrodes present and islets stay in good shape (Fig. 4B). Note that Islet chips were prepared before the perfusion experiments and we did not observe any islet detachment during recording (which would result in loss of signals). Simulations of flow dynamics (Fig. 4C) in the presence of islets revealed shear stress mainly at the top of the islets, but the maximal value of >0.5 mPa predicted at a flow rate of 1 µl/min remains still below values that have been reported in other islet devices44,45 or declared as critical46.

A–C Microfluidic microelectrode array. A Layout of microfluidic MEA. Channel length 10 mm, diameter 0.8 mm. B Left panel, view of a microfluidic PDMS device on a MEA, inlet and outlet are visible. White arrows, border of the PDMS device; yellow arrows, µMEA channel. Right panel, zoom on islets and electrodes in the microfluidic channel; yellow arrows, lateral borders of the channel. C Rainbow view of the shear stress at a flow-rate of 1 µl/min in the presence of islets. Views are either as z axis repartition over the channel or as top view at different heights (z). All dimensions are in mm. D–G Experimental values for one animal given as representative example. D Respiration frequency (Hz) of anaesthetized rat. E Blood glucose levels (upper panel) and dialysate glucose levels (lower panel), arrows indicate intraperitoneal glucose (ip, blue) injection or intraperitoneal insulin injections (black). To provide coherent read-outs in relation to the electrophysiological signals, lag times generated by dialysis and the microfluidic system versus blood glucose were considered as given in the “Methods”. Example of islet electrical activity in terms of slow potential frequencies (F) or amplitudes (G). Arrows indicate time of glucose or insulin injection. n = 11. H–K Correlation between electrical signal and blood and dialysate glucose levels from experiments in 4 (dialysate) to 5 (blood glucose) animals without insulin injection (N = 4–5 animals; n, electrodes in MEA, 4–11). H Linear regressions between glucose levels and slow potential frequencies. Each color represents one experiment (animal) and corresponding coefficients of determination R2 are indicated. Data points represents AUCs for a given blood glucose value and regression curves are given. I Linear regressions between blood glucose levels and slow potential amplitudes. Color codes as in (A), corresponding R2 values are indicated. J Spearman correlation over the entire blood glucose range during experiments for slow potential frequencies vs amplitudes (gray) as well as for frequency (open circles) and amplitudes (filled circles) versus glucose values either in blood (red) or in dialysate (blue). Each data point represents one experiment (animal), mean and SEMs are given. K Distribution of slopes vs R2 values for slow potential frequencies or amplitudes. R2 and slope values are from regression analyses between electrical signals and blood (red) or dialysate (blue) glucose levels, each point represents one animal.

We coupled this optimized µMEA to microdialysis at a flow rate of 1 µl/min. We compared electrical activity profiles of the biosensor with blood and dialysate glucose values as an indicator for its potential usefulness in continuous nutrient monitoring. As an independent control of the condition of the animal, we controlled respiration rates. Moreover, differences in breathing might also influence the performance of the interscapular microdialysis catheter and could introduce mechanical artefacts on the biosensor device. As given in Fig. 4D, respiration rate was stable and in a normal range of 1 Hz throughout the entire procedure. After a first glucose injection, we observed a rapid increase in blood glucose which reached its maximum after 40–60 min, whereas dialysate glucose was retarded by around 10 min. Both measures were discontinuous as the low microdialysis flow rate requires a minimal collection volume and time for subsequent glucose determination. To provide coherent read-outs in relation to the electrophysiological signals, lag times generated by dialysis and the microfluidic system versus blood glucose (Fig. 4E) were taken into account as given in the Methods. The increase in glucose was mirrored by an increase in electrical activity in terms of SP frequency and amplitude. For both a peak was attained at 60–70 min followed by a decrease in line with glucose concentrations (Fig. 4F, G). Note that, as expected, the slow physiological increase in glucose here did not induce a biphasic electrical response in contrast to the clear presence of biphasic pattern after stepwise increases in glucose (Figs. 2B and 3C). To test the reactivity of the system, insulin was injected and as expected blood as well as dialysate glucose levels decreased correspondingly. Subsequently to both injections of insulin a marked decrease in electrical activity was apparent (Fig. 4F, G).

In contrast to in vitro systems, where precise concentrations can be imposed, the absolute changes and kinetics in glycemia varied among animals. Moreover, the electrical activity of the biosensor islets is monitored at a microsecond scale, whereas blood or interstitial glucose is measured at far greater intervals. To obtain insight about the correlation between blood or interstitial glucose and biosensor responses we calculated the AUCs of electrical responses over the same time span as the fluid collection span for four (dialysate glucose) or five (blood glucose) independent experiments to compare equal time spans. Linear regression analysis for each independent experiment provided a set of graphs that were highly parallel in the case of SP frequencies whereas variable slopes were observed for amplitudes (Fig. 4H, I). Analyses for dialysate glucose are given in Supplementary Fig. S3 and a comprehensive view of Spearman’s ρ values is provided in Fig. 4J. Each of these correlations for a given experiment was highly significant (Supplementary Table 1). The biosensor response in terms of frequencies versus amplitudes was highly correlated as were electrical activities (frequencies and amplitudes) versus blood glucose levels with means around 0.9. The correlation between electrical responses and dialysate were more scattered which may be due to its measurement after passage through the microfluidic MEA and potential diffusion phenomena especially at low flow rates. However, they were still highly significative for association with Spearman’s ρ values mean values (Fig. 4J and Supplementary Table 1). The scatter plot in Fig. 4K shows the coefficient of determination of linear regressions and the identified slopes, which measure the linearly dependent nature of the studied metrics regardless of basal values. The spread of values on either axis visualizes the homogeneity of the results across experiments. As such, the clustering of our experimental values in the scatter plot reflects the repeatability of the fold increases in the studied metric relative to basal conditions. The data also indicate a more homogeneous distribution of effects on frequency as compared to amplitudes.

Discussion

Continuous monitoring of nutrient levels remains a major challenge in diabetes therapy and despite a remarkable progress over the last 50 years, an autonomous closed loop system is still not available4,5,47. Our work here demonstrates the feasibility of a label free microorgan-based biosensor and its recording of a clinical important parameter.

The major novelty of our approach relies on the fact that our biosensor is micro-organ-based, i.e., islets, as compared to the current biosensors in diabetes which use only one protein (enzyme), glucose oxidase, but do not harness the potential power of cellular or micro-organ signal treatment. For example, in islets, the activity of insulin-secreting β-cells is strongly modulated by α and δ cells48,49 An islet microorgan-based sensor provides a read-out that takes the effect of these physiological modulators into account. This has never been done before, except for biological tongues using taste buds3. Thus, the signal is already computed and modulated by the physiological micro-organ and a wider array of relevant signals is recognized (i.e., amino acids, hormones). Moreover, as shown before, this sensor reproduces the physiologically relevant hysteresis with an enhanced sensitivity during downfall of glucose levels and therefore a kind of safety mechanism against hypoglycemia. The advantage of this is not only evident through theoretical considerations but has also been shown by us directly using the FDA-approved UVA/PADOVA simulator36,37. This is also in line with the increasing awareness of the importance of other, non-β islet cells in glycemia regulation and diabetes50. The existing solutions have provided tremendous progress, but are still far away from user-independent (autonomous) function and need constant user-intervention. Our sensor contains the possibility to work truly without user intervention.

The hyperglycemic environment of type 1 diabetes may constitute a risk for an islet-based sensor as persistent marked hyperglycemia will deteriorate islet function. However, the time in range (TIR) value of more than 70% of time (glycemia below 9 mmol/l and more than 3.5 mmol/l) is expected in treated T1D and islets remain well functional at prolonged culture at 8 or even 10 mmol glucose51. Thus, the risk of sensor damage due to persistent hyperglycemia seems minor. The existing solutions have provided tremendous progress, but are still far away from user-independent (autonomous) function and need constant user-intervention. Our sensor contains the possibility to work truly without user intervention.

Regression analysis over a number of in vivo experiments indicates a remarkable homogeneity in terms of sensor responses to different glucose levels despite the variability in biological systems. In each experiment different animals as well as different preparation of islets for the biosensor were used and intrastrain variation in metabolic responses is well known52,53. As frequency and amplitudes of SPs were analyzed, the question arises whether one or the other quality is closer related to glucose levels. Previous in vitro experiments suggested that SP frequencies reflect insulin secretion more closely and this is further refined when taking also amplitudes into account29. However, in vitro experiments use strong square shaped stimulation by sudden increase in glucose and provoke a biphasic response. Such a biphasic response was apparent here only upon sudden increase by externally applied steps of 9 or more mM glucose but not during slow increases when coupled to microdialysis. The existence of biphasic activity and secretion in vivo in man is debated and may be absent during absorption of a meal54. Our data suggest that a frequency-based analysis may be more robust during in vivo applications. This may be due to the fact that frequency is independent from the distance between islets and electrodes in contrast to amplitudes and that this distance may vary depending on the thickness of the extracellular matrix. Interestingly, the biosensor reacted strongly to insulin injection despite a minor concomitant decreases in blood and dialysate glucose. It is known that glucose dependency of insulin secretion displays a hysteresis when comparing increases versus decreases in glucose levels in man in vivo21. This serves as a kind of safety break to avoid hypoglycemia and is also found in isolated islets in vitro22. Although we have not investigated the existence of a hysteresis here, one may speculate that the considerable decrease upon insulin injection observed here may be due to such an islet mechanism. This reduction in electrical activity also reflects the concept that electrical islet signals are shaped not only by glucose levels but also the need in insulin that obviously declines after exogenous delivery despite smaller decreases in blood glucose levels.

Sensors in biological circuits (in vivo, ex vivo) may be subject to sensor fouling and islet viability. As the sensors here are metal electrodes without any enzyme attached, but protected by a cell layer, fouling is less likely. Moreover, we have directly tested this previously in either static or microfluidic settings and did not find any degradation or any issue related to islet viability after several days or a week26. Recovery rate was 78% and thus the highest glucose levels seen by the biosensor are lower than those in vivo. This should not be a problem provided that the control mechanism (algorithm) that controls the actuator, i.e., an insulin-pump, reacts mainly to changes in kinetics, such as signal increase or decrease, instead to absolute values.

We have also projected a possible packaging of an islet-based biosensor (Supplementary Fig. S4), including microdialysis and an insulin reservoir. Although the qualities of a micro-organ biosensor are evident, there are also limitations and obstacles. In contrast to enzyme-based electrochemical sensors, microdialysis is necessary with concomitant space requirements and device duration55,56. As islet encapsulation techniques are constantly evolving, direct implantation of such a device may eventually be possible in the future57. A clear limitation is given by the type of islets to be used in the sensor. Reaggregated human donor islets exhibit excellent function58 but may raise ethical issues by diverting islets from use in transplantation. Alternatively, stem cell-derived β-cell-like cells have attained considerable functional maturity in vitro59.

The device developed here may also serve to investigate micro-organ function, including iPSC-derived surrogate islets, under more physiological conditions than in-vitro27,60. Our approach may also be rather useful to develop novel bio-inspired algorithms in conjunction with the FDA-approved UVA Padova simulator36,37. The major novelty of our approach relies on the fact that our biosensor is micro-organ-based, i.e., islets, as compared to the current biosensors in diabetes which use only one protein (enzyme), glucose oxidase, but do not harness the potential power of cellular or micro-organ signal treatment. This has never been done before, except for biological tongues using taste buds. Thus, the signal is already computed and modulated by the physiological micro-organ and a wider array of relevant signals is recognized (i.e., amino acids, hormones). Moreover, as shown before, this sensor reproduces the physiologically relevant hysteresis with an enhanced sensitivity during downfall of glucose levels and therefore a kind of safety mechanism against hypoglycemia. The advantage of this is not only evident through theoretical considerations but has also been shown by us directly using the FDA-approved UVA/PADOVA simulator36,37. This is also in line with the increasing awareness of the importance of other, non-β islet cells in glycemia regulation and diabetes17,18. The existing solutions have provided tremendous progress, but are still far away from user-independent (autonomous) function and need constant user-intervention. Our sensor contains the possibility to work truly without user intervention.

In conclusion, a number of biosensors have been developed in the past relying on electrodes, enzymes, genetically encoded fluorescent probes or genetically modified micro-organisms61,62. Cells receive various information from their environment and compute the appropriate output almost instantaneously on a millisecond scale. Although developing biosensors to harness the inherent analytic power of micro-organs or tissues faces a considerable number of technical obstacles2, progress has been achieved especially in the field of bioelectronic tongues3. To the best of our knowledge those biosensors have not been interfaced to an entire organism with the goal to achieve homeostatic control. Our work here provides a further step in the development of micro-organ-based biosensors.

Methods

Animals, surgery and islet preparation

Animal experiences were conducted along ethical guidelines and authorized (APAFIS #25037-2020040917179466) by the French Ministry of Research and Innovation. Male Wistar rats (Charles River, Lyon, France), mean age 10.4 weeks and with a mean weight of 384 g were placed on a heated pad and anaesthetized with isoflurane (starting with 3.5% in air, 2 l/min; maintenance by 1.5% in air) and for analgesia meloxicam was given subcutaneously (1 mg/kg) 30 min before implantation of the catheter as well as a local anesthetic was applied (lidocaine 2.5% cream). To insert the microdialysis catheter a small incision was placed on the interscapular area after shaving and disinfection with a povidone-iodine antiseptic (vetedine). At the end of the experiment, rats were euthanized by ip injection of pentobarbital (200 mg/kg) and lidocaine (20 mg/kg). For islet isolations, adult male C57BL/6J mice (10–20 weeks of age) were sacrificed by cervical dislocation according to University of Bordeaux ethics committee guidelines. Islets were obtained by enzymatic digestion and handpicking. MEAs were coated with Matrigel (2% v/v) (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA) as described22,29,32. Islets were seeded on MEAs and cultured for 3 days at 37 °C.

Microfluidic MEA chips

For dynamic experiments, a microchannel was fabricated with PDMS-based elastomer Sylgard 184 (Dow Corning, St Denis, France) and the microchannel was fabricated by using a SU-8 mold patterned with a channel of 0.8 mm in diameter and 10 mm in length. PDMS on the mold was cured by 2 h of heating at 70 °C. The microchannels where subsequently aligned on the MEAs under a microscope in a cleanroom, and bonded thanks to a previous O2-plasma activation. For static incubations, the chip consisted of a PDMS microwell of 3 mm in diameter and in height. Fluid shear stress was computed with the Multiphysics simulation software COMSOL 6.1 (COMSOL, Inc., Burlington, MA). First, a 3D stationary simulation was carried out where the flow in the microfluidic channel is simulated following Navier Stokes equations, with a laminar flow boundary condition at the inlet. The inlet is defined in a flow rate manner, with the flow rate of 1 µl/min as used in the experiments. The shear stress is deduced from the results of the study using the following definition: τ = μ∆u where μ is the dynamic viscosity of water at 37 °C and u is the velocity field. The pancreatic islets were loaded into the microfluidic chip by gentle pipetting after their isolation and cultured for 3 days before use. Briefly, islets in culture medium were introduced into the straight microchannel of the chip using a 10 µL pipette. The device was left undisturbed for 2 h to allow the islets to settle within the channel. After this initial settling period, the entire microfluidic chip was carefully covered with culture medium to prevent evaporation and to allow gentle medium renewal during culture. The position of the islets within the channel was verified using a microscope immediately after loading. No specific dam walls or hydrodynamic traps were used; the islets remained within the channel primarily by gravity and the confined geometry of the straight microchannel.

Analysis of delays in fluid transport in MEA chips and respiration rate of anesthetized rats

The delay introduced by the transit of dialysate from the subcutaneous site to its arrival in the microfluidic MEA chamber and final glucose determination after passage through the microfluidic chip and tubes was determined through analysis of videos during phenol red perfusions of the chip under conditions identical to experimental conditions, i.e., from microdialysis to dialysate collection (for details see Fig. S1). Delays generated by microdialysis/microfluidics were adjusted for graphical presentation and correlation analysis. The delay Δt_SQ was estimated using cross-correlation between electrophysiological recordings and windowed AUCs of DG measurements: In practical terms, cross-correlation is a mathematical tool that compares compare two time series by shifting one relative to the other and quantifies how similar they are at each shift. The point where the similarity (correlation) reaches its peak indicates how much one signal lags behind the other. In our case, the electrophysiological signal and the dialysate glucose measurement were aligned by finding the time shift corresponding to the peak of the cross-correlation function. This value was taken as the diffusion delay Δt_SQ. Because physiological responses can differ between animals, Δt_SQ was calculated separately for each experiment. The respiration rate of anaesthetized rats was measured through analysis of video files, using an ad hoc program written in Python that detects oscillating movement on the rat’s fur. For details, see Fig. S2.

Electrophysiology

MEAs (60 MEA200/30iR-TiN, Ø 30 mm, 200 mm interelectrode distance) were purchased from Multi Channel Systems GmbH (MCS, Reutlingen, Germany). As described previously23,29,32, extracellular field potentials were acquired at 10 kHz, amplified, and band-pass filtered at 0.1–3000 Hz with a USB-MEA60-Inv-System-E amplifier (MCS; gain: 1200) or an MEA1060-Inv-BC-Standard amplifier (MCS; gain: 1100), both controlled by MC_Rack software (v4.6.2, MCS). Electrophysiological data were analyzed with MC_Rack software. SPs were isolated using a 2-Hz low-pass filter and frequencies were determined using the threshold module of MC_Rack with a dead time (minimal period between two events) of 300 ms (SPs). The peak-to-peak amplitude module of MC_Rack was used to determine SP amplitudes as published27. Only electrodes covered by islets were considered (covered vs non-covered islets can be distinguished by noise parameters63.

Microdialysis, glucose injections and measurements

Linear interscapular subcutaneous catheters (30 mm membrane, 20 kDa cut off; Microdialysis AB) were inserted under anesthesia (1.5% isoflurane in air). For dialysis, Ringer dextran-60 was used (pump 107, Microdialysis AB, Kista, Sweden). For glucose or insulin tests, 2 g/kg of glucose or 2.5 U/kg of insulin were injected intraperitoneally. Blood glucose was measured in droplets collected at the caudal vein with a freestyle papillon glucometer (Abbott, Rungis, France). Glucose in the dialysate was determined using a glucose oxidase-based kit (Biolabo, Maizy, France). Human male plasma was obtained from Sigma (H4522; Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA) and contained 6 mM glucose.

Statistics

Correlations between electrophysiological data (SP frequencies and SP amplitudes) and glucose measurements (capillary and dialysate) were calculated using Spearman correlation in Python (Python 3.7, scipy 1.3.0). Electrophysiological data were resampled using windowed AUCs (see below) prior to correlation, in order to match glucose measurements. For correlation the AUC of electrophysiological data (SP frequencies and SP amplitudes) were calculated using the trapezoidal rule in time windows surrounding each glucose measurement (capillary or dialysate): AUCs used for correlation with blood glucose (BG) measurements were calculated in a [−90 s; +90 s] time window around each BG data point; AUCs used for correlation with dialysate glucose (DG) measurements were calculated in a [+0 s; +900 s] time window following each DG data point, identical to the window of dialysate collection for the corresponding DG measurement. The distinction between time windows was made because capillary blood glucose measurements were punctual (representative of a short time window), whereas the collection of dialysate samples spanned over 15 min each (representative of a 15 min time window). The diffusion delay Δt_SQ was estimated using cross-correlation between electrophysiological data and windowed AUCs of DG measurements. Δt_SQ was measured at peak correlation for each experiment individually, as it was assumed to be animal-dependent. Other statistical analyses of electrophysiological data were performed using GraphPad PRISM v7.00 (San Diego, CA, USA) with ANOVA and post-hoc tests (Dunn or Tukey) as given in the Figure legends. Data are provided as mean ± SEM. N correspond to the numbers of independent experiments (different MEAs with different islets from different animals or in vivo experiments with different animals and different MEAs), n correspond to the number of electrodes per experiment.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to format constraints, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

Codes used here (respiration rate; Spearman correlations) are available upon reasonable request.

References

-

Flynn, C. D. et al. Biomolecular sensors for advanced physiological monitoring. Nat. Rev. Bioeng. 1, 16 (2023).

-

Gupta, N., Renugopalakrishnan, V., Liepmann, D., Paulmurugan, R. & Malhotra, B. D. Cell-based biosensors: Recent trends, challenges and future perspectives. Biosens. Bioelectron. 141, 111435 (2019).

-

Tian, Y., Wang, P., Du, L. & Wu, C. Advances in gustatory biomimetic biosensing technologies: in vitro and in vivo bioelectronic tongue. Trends Anal. Chem. 157, 116778 (2022).

-

Lee, I., Probst, D., Klonoff, D. & Sode, K. Continuous glucose monitoring systems – Current status and future perspectives of the flagship technologies in biosensor research. Biosens. Bioelectron. 181, 113054 (2021).

-

Teo, E., Hassan, N., Tam, W. & Koh, S. Effectiveness of continuous glucose monitoring in maintaining glycaemic control among people with type 1 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials and meta-analysis. Diabetologia https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-021-05648-4 (2022).

-

Federation, I. D. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 10th edn. Available at: https://www.diabetesatlas.org (2021).

-

Ashcroft, F. M. & Rorsman, P. Diabetes mellitus and the β cell: the last ten years. Cell 148, 1160–1171 (2012).

-

Pigeyre, M. et al. Validation of the classification for type 2 diabetes into five subgroups: a report from the ORIGIN trial. Diabetologia 65, 206–215 (2022).

-

Charles, M. A. & Leslie, R. D. Diabetes: concepts of β-cell organ dysfunction and failure would lead to earlier diagnoses and prevention. Diabetes 70, 2444–2456 (2021).

-

Quattrin, T., Mastrandrea, L. D. & Walker, L. S. K. Type 1 diabetes. Lancet 401, 2149–2162 (2023).

-

Cinar, A. et al. Metabolic models, in silico trials, and algorithms. Diab. Technol. Ther. 27, S21–S32 (2025).

-

Sherr, J. L. et al. Automated insulin delivery: benefits, challenges, and recommendations. A consensus report of the joint diabetes technology working group of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes and the American Diabetes Association. Diabetologia 66, 3–22 (2023).

-

Rorsman, P. & Braun, M. Regulation of insulin secretion in human pancreatic islets. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 75, 155–179 (2012).

-

De Marinis, Y. Z. et al. GLP-1 inhibits and adrenaline stimulates glucagon release by differential modulation of N- and L-type Ca2+ channel-dependent exocytosis. Cell Metab. 11, 543–553 (2010).

-

Falkmer, S. Immunocytochemical studies of the evolution of islet hormones. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 27, 1281–1282 (1979).

-

Youson, J. H. & Al-Mahrouki, A. A. Ontogenetic and phylogenetic development of the endocrine pancreas (islet organ) in fish. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 116, 303–335 (1999).

-

Noguchi, G. M. & Huising, M. O. Integrating the inputs that shape pancreatic islet hormone release. Nat. Metab. 1, 1189–1201 (2019).

-

Campbell, J. E. & Newgard, C. B. Mechanisms controlling pancreatic islet cell function in insulin secretion. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 22, 142–158 (2021).

-

Garzilli, I. & Itzkovitz, S. Design principles of the paradoxical feedback between pancreatic alpha and beta cells. Sci. Rep. 8, 10694 (2018).

-

Jo, J., Choi, M. Y. & Koh, D. S. Beneficial effects of intercellular interactions between pancreatic islet cells in blood glucose regulation. J. Theor. Biol. 257, 312–319 (2009).

-

Keenan, D. M. et al. Logistic model of glucose-regulated C-peptide secretion: hysteresis pathway disruption in impaired fasting glycemia. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 303, E397–E409 (2012).

-

Lebreton, F. et al. Slow potentials encode intercellular coupling and insulin demand in pancreatic beta cells. Diabetologia 58, 1291–1299 (2015).

-

Perrier, R. et al. Bioelectronic organ-based sensor for microfluidic real-time analysis of the demand in insulin. Biosens. Bioelectron. 117, 253–259 (2018).

-

Pirog, A. et al. Multimed: An Integrated, multi-application platform for the real-time recording and sub-millisecond processing of biosignals. Sensors 18 https://doi.org/10.3390/s18072099 (2018).

-

Virgilio, E. et al. Recessive TMEM167A variants cause neonatal diabetes, microcephaly and epilepsy syndrome. J. Clin. Investig. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci195756 (2025).

-

Lallouet, M. et al. A microfluidic twin islets-on-chip device for on-line electrophysiological monitoring. Lab Chip 25, 1831–1841 (2025).

-

Jaffredo, M. et al. Electrophysiological characterisation of iPSC-derived human β-like cells and an SLC30A8 disease model. Diabetes https://doi.org/10.2337/db23-0776 (2024).

-

Raoux, M. et al. Islets-on-Chip: a tool for real-time assessment of islet function prior to transplantation. Transpl. Int 36, 11512 (2023).

-

Jaffredo, M. et al. Dynamic uni- and multicellular patterns encode biphasic activity in pancreatic islets. Diabetes 70, 878–888 (2021).

-

Raoux, M. et al. Multilevel control of glucose homeostasis by adenylyl cyclase 8. Diabetologia 58, 749–757 (2015).

-

Raoux, M. et al. Non-invasive long-term and real-time analysis of endocrine cells on micro-electrode arrays. J. Physiol. 590, 1085–1091 (2012).

-

Abarkan, M. et al. Vertical organic electrochemical transistors and electronics for low amplitude micro-organ signals. Adv. Sci. 9, e2105211 (2022).

-

Abarkan, M. et al. The glutamate receptor GluK2 contributes to the regulation of glucose homeostasis and its deterioration during aging. Mol. Metab. 30, 152–160 (2019).

-

Thompson, B. & Satin, L. S. Beta-Cell ion channels and their role in regulating insulin secretion. Compr. Physiol. 11, 1–21 (2021).

-

Cobelli, C. & Kovatchev, B. Developing the UVA/Padova type 1 diabetes simulator: modeling, validation, refinements, and utility. J. Diab. Sci. Technol. 17, 1493–1505 (2023).

-

Olcomendy, L. et al. Towards the integration of an islet-based biosensor in closed-loop therapies for patients with type 1 Diabetes. Front. Endocrinol. 13, 795225 (2022).

-

Olcomendy, L. et al. Integrating an islet-based biosensor in the artificial pancreas: in silico proof-of-concept. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 69, 899–909 (2022).

-

Shippenberg, T. S. & Thompson, A. C. Overview of microdialysis. Curr. Protoc. Neurosci. https://doi.org/10.1002/0471142301.ns0701s00 (1997).

-

Basu, A. et al. Time lag of glucose from intravascular to interstitial compartment in humans. Diabetes 62, 4083–4087 (2013).

-

Aussedat, B. et al. Interstitial glucose concentration and glycemia: implications for continuous subcutaneous glucose monitoring. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 278, E716–E728 (2000).

-

Bosco, D., Haefliger, J. A. & Meda, P. Connexins: key mediators of endocrine function. Physiol. Rev. 91, 1393–1445 (2011).

-

Henquin, J. C. Regulation of insulin secretion: a matter of phase control and amplitude modulation. Diabetologia 52, 739–751 (2009).

-

Kim, A. et al. Islet architecture: a comparative study. Islets 1, 129–136 (2009).

-

Glieberman, A. L. et al. Synchronized stimulation and continuous insulin sensing in a microfluidic human Islet on a Chip designed for scalable manufacturing. Lab Chip 19, 2993–3010 (2019).

-

Eaton, W. J. & Roper, M. G. A microfluidic system for monitoring glucagon secretion from human pancreatic islets of Langerhans. Anal. Methods 13, 3614–3619 (2021).

-

Silva, P. N., Green, B. J., Altamentova, S. M. & Rocheleau, J. V. A microfluidic device designed to induce media flow throughout pancreatic islets while limiting shear-induced damage. Lab Chip 13, 4374–4384 (2013).

-

Cobelli, C., Renard, E. & Kovatchev, B. Artificial pancreas: past, present, future. Diabetes 60, 2672–2682 (2011).

-

Huising, M. O., van der Meulen, T., Huang, J. L., Pourhosseinzadeh, M. S. & Noguchi, G. M. The difference δ-cells make in glucose control. Physiology 33, 403–411 (2018).

-

Gilon, P. The role of α-cells in islet function and glucose homeostasis in health and type 2 diabetes. J. Mol. Biol. 432, 1367–1394 (2020).

-

Gromada, J., Chabosseau, P. & Rutter, G. A. The α-cell in diabetes mellitus. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 14, 694–704 (2018).

-

Tariq, M. et al. Prolonged culture of human pancreatic islets under glucotoxic conditions changes their acute beta cell calcium and insulin secretion glucose response curves from sigmoid to bell-shaped. Diabetologia 66, 709–723 (2023).

-

Rose, R., Kheirabadi, B. S. & Klemcke, H. G. Arterial blood gases, electrolytes, and metabolic indices associated with hemorrhagic shock: inter- and intrainbred rat strain variation. J. Appl. Physiol. 114, 1165–1173 (2013).

-

Rothwell, N. J. & Stock, M. J. Intra-strain differences in the response to overfeeding in the rat. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 39, 20a (1980).

-

Rorsman, P. & Ashcroft, F. M. Pancreatic beta-cell electrical activity and insulin secretion: Of mice and men. Physiol. Rev. 98, 117–214 (2018).

-

Ricci, F. et al. Toward continuous glucose monitoring with planar modified biosensors and microdialysis. Study of temperature, oxygen dependence and in vivo experiment. Biosens. Bioelectron. 22, 2032–2039 (2007).

-

Ricci, F. et al. Novel planar glucose biosensors for continuous monitoring use. Biosens. Bioelectron. 20, 1993–2000 (2005).

-

Yang, K. et al. A therapeutic convection-enhanced macroencapsulation device for enhancing β cell viability and insulin secretion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118 https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2101258118 (2021).

-

Sachs, S. et al. Targeted pharmacological therapy restores β-cell function for diabetes remission. Nat. Metab. 2, 192–209 (2020).

-

Balboa, D. et al. Functional, metabolic and transcriptional maturation of human pancreatic islets derived from stem cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 40, 1042–1055 (2022).

-

Glieberman, A. L., Pope, B. D., Melton, D. A. & Parker, K. K. Building biomimetic potency tests for islet transplantation. Diabetes 70, 347–363 (2021).

-

Faheem, A. & Cinti, S. Non-invasive electrochemistry-driven metals tracing in human biofluids. Biosens. Bioelectron. 200, 113904 (2022).

-

Reddy, B., Salm, E. & Bashir, R. Electrical chips for biological point-of-care detection. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 18, 329–355 (2016).

-

Pirog, A. et al. A versatile electrode sorting module for MEAs: Implementation in a FPGA-based real-time system. In Proc. IEEE Biomedical Circuits and Systems Conference (BioCAS 2017), pp. 1–4. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/8325154.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Céline Cruciani-Guglielmacci and Christophe Magnan for helpful advices on surgery.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Puginier, E., Pirog, A., de Gannes, F.P. et al. A micro-organ based microfluidic biosensor for continuous monitoring of glucose levels in vivo. npj Biosensing 3, 12 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44328-025-00077-4

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

Version of record:

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44328-025-00077-4