Data availability

The primary data related to the results of this study can be found within the paper and its Supplementary Information. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The code used for protein sequence analysis in this study is available on GitHub (https://github.com/fangzhe3/MVP_code)52.

References

-

August, A. et al. Safety and immunogenicity of an mRNA-based human metapneumovirus and parainfluenza virus type 3 combined vaccine in healthy adults. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 9, ofac206 (2022).

-

John, S. et al. Multi-antigenic human cytomegalovirus mRNA vaccines that elicit potent humoral and cell-mediated immunity. Vaccine 36, 1689–1699 (2018).

-

Awasthi, S. & Friedman, H. M. An mRNA vaccine to prevent genital herpes. Transl. Res. 242, 56–65 (2022).

-

Lee, S. et al. mRNA-HPV vaccine encoding E6 and E7 improves therapeutic potential for HPV-mediated cancers via subcutaneous immunization. J. Med. Virol. 95, e29309 (2023).

-

Zhang, P. et al. A multiclade env–gag VLP mRNA vaccine elicits tier-2 HIV-1-neutralizing antibodies and reduces the risk of heterologous SHIV infection in macaques. Nat. Med. 27, 2234–2245 (2021).

-

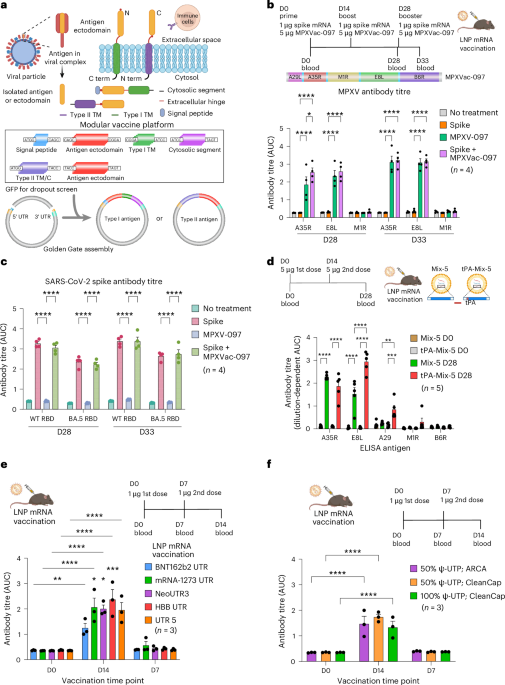

Fang, Z. et al. Polyvalent mRNA vaccination elicited potent immune response to monkeypox virus surface antigens. Cell Res. 33, 407–410 (2023).

-

Monslow, M. A. et al. Immunogenicity generated by mRNA vaccine encoding VZV gE antigen is comparable to adjuvanted subunit vaccine and better than live attenuated vaccine in nonhuman primates. Vaccine 38, 5793–5802 (2020).

-

Essink, B. et al. The safety and immunogenicity of two Zika virus mRNA vaccine candidates in healthy flavivirus baseline seropositive and seronegative adults: the results of two randomised, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging, phase 1 clinical trials. Lancet Infect. Dis. 23, 621–633 (2023).

-

Barbier, A. J., Jiang, A. Y., Zhang, P., Wooster, R. & Anderson, D. G. The clinical progress of mRNA vaccines and immunotherapies. Nat. Biotechnol. 40, 840–854 (2022).

-

Pardi, N., Hogan, M. J., Porter, F. W. & Weissman, D. mRNA vaccines—a new era in vaccinology. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 17, 261–279 (2018).

-

Freed, D. C. et al. Pentameric complex of viral glycoprotein H is the primary target for potent neutralization by a human cytomegalovirus vaccine. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, E4997–E5005 (2013).

-

He, Y. et al. Antibodies to the A27 protein of vaccinia virus neutralize and protect against infection but represent a minor component of Dryvax vaccine-induced immunity. J. Infect. Dis. 196, 1026–1032 (2007).

-

Kaever, T. et al. Linear epitopes in vaccinia virus A27 are targets of protective antibodies induced by vaccination against smallpox. J. Virol. 90, 4334–4345 (2016).

-

Li, M. et al. Three neutralizing mAbs induced by MPXV A29L protein recognizing different epitopes act synergistically against orthopoxvirus. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 12, 2223669 (2023).

-

Xia, H., He, Y. R., Zhan, X. Y. & Zha, G. F. Mpox virus mRNA-lipid nanoparticle vaccine candidates evoke antibody responses and drive protection against the vaccinia virus challenge in mice. Antivir. Res. 216, 105668 (2023).

-

Kreiter, S. et al. Mutant MHC class II epitopes drive therapeutic immune responses to cancer. Nature 520, 692–696 (2015).

-

Ramos da Silva, J. et al. Single immunizations of self-amplifying or non-replicating mRNA-LNP vaccines control HPV-associated tumors in mice. Sci. Transl. Med. 15, eabn3464 (2023).

-

Harper, D. M. et al. Efficacy of a bivalent L1 virus-like particle vaccine in prevention of infection with human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 in young women: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 364, 1757–1765 (2004).

-

Tan, M. Norovirus vaccines: current clinical development and challenges. Pathogens 10, 1641 (2021).

-

Dattwyler, R. J. & Gomes-Solecki, M. The year that shaped the outcome of the OspA vaccine for human Lyme disease. npj Vaccines 7, 10 (2022).

-

Bonam, S. R., Renia, L., Tadepalli, G., Bayry, J. & Kumar, H. M. S. Plasmodium falciparum malaria vaccines and vaccine adjuvants. Vaccines 9, 1072 (2021).

-

Polack, F. P. et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 383, 2603–2615 (2020).

-

Baden, L. R. et al. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 403–416 (2021).

-

Fang, Z. et al. Heterotypic vaccination responses against SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.2. Cell Discov. 8, 69 (2022).

-

Sample, P. J. et al. Human 5′ UTR design and variant effect prediction from a massively parallel translation assay. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 803–809 (2019).

-

Leppek, K. et al. Combinatorial optimization of mRNA structure, stability, and translation for RNA-based therapeutics. Nat. Commun. 13, 1536 (2022).

-

Cao, J. et al. High-throughput 5′ UTR engineering for enhanced protein production in non-viral gene therapies. Nat. Commun. 12, 4138 (2021).

-

Henderson, J. M. et al. Cap 1 messenger RNA synthesis with co-transcriptional CleanCap® analog by in vitro transcription. Curr. Protoc. 1, e39 (2021).

-

Kariko, K., Buckstein, M., Ni, H. & Weissman, D. Suppression of RNA recognition by Toll-like receptors: the impact of nucleoside modification and the evolutionary origin of RNA. Immunity 23, 165–175 (2005).

-

Hoffmann, M. A. G. et al. ESCRT recruitment to SARS-CoV-2 spike induces virus-like particles that improve mRNA vaccines. Cell 186, 2380–2391.e9 (2023).

-

Berger, A. Th1 and Th2 responses: what are they? Br. Med. J. 321, 424 (2000).

-

Romagnani, S. T-cell subsets (Th1 versus Th2). Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 85, 9–18 (2000).

-

Cheng, X. et al. A synergistic lipid nanoparticle encapsulating mRNA shingles vaccine induces potent immune responses and protects guinea pigs from viral challenges. Adv. Mater. 36, e2310886 (2024).

-

Tao, M., Kruhlak, M., Xia, S., Androphy, E. & Zheng, Z. M. Signals that dictate nuclear localization of human papillomavirus type 16 oncoprotein E6 in living cells. J. Virol. 77, 13232–13247 (2003).

-

Verbeke, R., Hogan, M. J., Lore, K. & Pardi, N. Innate immune mechanisms of mRNA vaccines. Immunity 55, 1993–2005 (2022).

-

Akkaya, M., Kwak, K. & Pierce, S. K. B cell memory: building two walls of protection against pathogens. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 20, 229–238 (2020).

-

Rock, K. L., Reits, E. & Neefjes, J. Present yourself! By MHC class I and MHC class II molecules. Trends Immunol. 37, 724–737 (2016).

-

Kreiter, S. et al. Increased antigen presentation efficiency by coupling antigens to MHC class I trafficking signals. J. Immunol. 180, 309–318 (2008).

-

Arieta, C. M. et al. The T-cell-directed vaccine BNT162b4 encoding conserved non-spike antigens protects animals from severe SARS-CoV-2 infection. Cell 186, 2392–2409.e21 (2023).

-

Zuiani, A. et al. A multivalent mRNA monkeypox virus vaccine (BNT166) protects mice and macaques from orthopoxvirus disease. Cell 187, 1363–1373.e12 (2024).

-

Weber, J. S. et al. Individualised neoantigen therapy mRNA-4157 (V940) plus pembrolizumab versus pembrolizumab monotherapy in resected melanoma (KEYNOTE-942): a randomised, phase 2b study. Lancet 403, 632–644 (2024).

-

Rojas, L. A. et al. Personalized RNA neoantigen vaccines stimulate T cells in pancreatic cancer. Nature 618, 144–150 (2023).

-

Cafri, G. et al. mRNA vaccine-induced neoantigen-specific T cell immunity in patients with gastrointestinal cancer. J. Clin. Invest. 130, 5976–5988 (2020).

-

Moffat, J. et al. Functions of the C-terminal domain of varicella-zoster virus glycoprotein E in viral replication in vitro and skin and T-cell tropism in vivo. J. Virol. 78, 12406–12415 (2004).

-

Barash, S., Wang, W. & Shi, Y. Human secretory signal peptide description by hidden Markov model and generation of a strong artificial signal peptide for secreted protein expression. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 294, 835–842 (2002).

-

Dai, X. et al. One-step generation of modular CAR-T cells with AAV–Cpf1. Nat. Methods 16, 247–254 (2019).

-

Reiss, S. et al. Comparative analysis of activation induced marker (AIM) assays for sensitive identification of antigen-specific CD4 T cells. PLoS ONE 12, e0186998 (2017).

-

Galvez, R. I. et al. Frequency of Dengue virus-specific T cells is related to infection outcome in endemic settings. JCI Insight 10, e179771 (2025).

-

Peng, L. et al. Variant-specific vaccination induces systems immune responses and potent in vivo protection against SARS-CoV-2. Cell Rep. Med. 3, 100634 (2022).

-

Ye, L. et al. A genome-scale gain-of-function CRISPR screen in CD8 T cells identifies proline metabolism as a means to enhance CAR-T therapy. Cell Metab. 34, 595–614.e14 (2022).

-

Fang, Z. et al. Omicron-specific mRNA vaccination alone and as a heterologous booster against SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Commun. 13, 3250 (2022).

-

Fang, Z. et al. fangzhe3 / MVP_code. GitHub https://github.com/fangzhe3/MVP_code (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by discretionary funds and a Cancer Research Institute Lloyd J. Old STAR Award (CRI4964) to S.C. We acknowledge support from various Yale core facilities: the Systems Biology Institute, Department of Genetics, Department of Immunobiology, Yale School of Medicine Dean’s Office and Office of the Vice Provost for Research. We thank X. Chen, L. Chen, F. Fenteany, L. Lawres, L. Zhou, K. Tang, X. Zhou, P. Ren and many other laboratory members and/or colleagues for providing reagents, suggestions and technical assistance. Z. Fang is supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (funding reference number 194053).

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

S.C. is a (co)founder of EvolveImmune Therapeutics, Cellinfinity Bio, MagicTime Medicine and Chen Consulting, all unrelated to this study. A patent application related to this study has been filed by Yale University. The patent titled ‘Compositions and Methods for Enhancement of mRNA Vaccine Performance and Vaccination Against Mpox’ (PCT International Appl. No. PCT/US2023/081090) covers the related biotechnology. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Biomedical Engineering thanks Anna Blakney and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Flow cytometry gating strategy to select A35R-positive 293T cells which overexpressed A35R ectodomain recombined with various N-term type II TM/Cs and were surface stained with PE anti-A35R antibody.

The 293T cells were gated at low and high threshold to define PE and PE-high populations, respectively (n = 3). The A35R TM/C + A35R ectodomain served as the internal control. The A35R ectodomains with endomembrane protein TM/Cs, such as TMX4, SEC11A, PM121, served as TM/C negative controls. The TM/C modules that outperformed A35R TM/C (orange) are highlighted in red or purple (color based on their located quadrants in Fig. 2a). Schematic (top right) created with BioRender.com.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Representative flow plots showing the gating strategies to define PE or PE-high positive 293T cells that overexpressed A29 with or without either [Spike SP] + type I TM/Cs (bottom panel) or Type II TM/Cs (top panel) and were surface stained with PE anti-A29 antibody.

The A35R TM/C + A29 served as the internal control, while the A29 with endomembrane protein type II TM/Cs, including TMX4 and SEC11A, served as TM/C negative controls. The TM/C modules that outperformed A35R TM/C (orange) are highlighted in red or purple (color based on their type I or type II topology). Schematic (top right) created with BioRender.com.

Extended Data Fig. 3 ELISA titration curves over serial dilutions of plasma collected on different days from mice immunized with 1 µg [CD8 SP]-M1Re LNP-mRNAs with different TM/Cs.

a, ELISA titration curves on days 0, 14, 21 and 35 (n = 5). The immunization schedule is shown at the top of the graph. b, correlation of antibody titers against M1R with corresponding antigen’s expression on 293T cells. The antigen expression as CST quantified by normalized PE integral (positive rate x positive MFI ratio) is plotted against anti-M1R antibody AUC titer. all data points except for the secreted M1Re is analyzed in linear regression. c, TM/C modules modulated the antibody and T cell response to LNP-mRNA of chimeric [CD8a SP]-M1Re in mice. The anti-M1R antibody titer on day 35 is plotted against Th1 response (IFN- γ as an indicator). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Schematic in a created with BioRender.com.

Extended Data Fig. 4 The CST scores were calculated from normalized antigen surface expression and were used to evaluate SP and TM/C modules’ strength to promote different Mpox antigens translocation to cell surface.

a,c, The fusion of flag-tagged (a) or untagged (c) [CD8a SP]-A29 with different type I TM/Cs enhanced its surface expression in 293T cells (n = 3). b,d, Various N-term signal peptides increased flag tagged A29-[HLA TM/C] (b) or E8L (d) surface expression levels (n = 3). e,f, The CST score was used to evaluate the signal strength of different SP (e) or TM/C (f) modules at promoting antigen expression on 293T cell surface. It is derived from normalized antigen expression, of which largest value in each dataset was normalized to 1. e, Various signal peptides (SP) increased cell-surface expression of flag-tagged Mpox antigens, including A29, M1Re and E8L (n = 3). f, Different type I TM/Cs improved cell-surface expression of flag-tagged or untagged A29 and M1Re in 293 T cells (n = 3). Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

Extended Data Fig. 5 T cells from mice vaccinated with MVP-modified mRNA antigens showed higher cytokine secretion after VZV or HPV antigen stimulation.

PBMCs were collected on day 28 from mice vaccinated different LNP mRNAs and stimulated with VZV gE antigen or HPV E6, E7 peptides for 18 and 30 hours. The secreted cytokines in media were measured by beads-based immunoassays (seen methods). a, Cytokine secretion of T cells stimulated with VZV gE antigen for 18 h (top) and 30 h (bottom). b, Cytokine secretion of T cells stimulated with HPV E6 and E7 scanning peptide pools for 18 h (top) and 30 h (bottom). All statistics were derived from Dunnett’s multiple comparison test between controls (VZV gE full length or HPV16 E6 + E7) and other treatment groups. PMA/Ionomycin group was excluded from comparisons. Sample number of vaccination groups (except for PMA/Ionomycin) is 5. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Dunnett’s comparison test was used to determine statistical significance between WT antigens and modified antigen groups. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001. Mouse icons created with BioRender.com.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Compared to E6 + E7 vaccination control, T cells collected on day 35 from mice vaccinated with MVP-modified E6 and E7 mRNA antigens showed higher target cell killing activity (a), activation induced markers (b) and cytokine secretion (c) after 18-hour co-culture with B16F10 target cells transduced with HPV16 wild-type E6 + E7 and pulsed with E6, E7 peptides.

a, T cells from mice vaccinated with MVP-modified E6, E7 mRNA antigens led to higher cytolysis of B16F10 target cells (n = 5). b, Activation induced markers were surface stained in T cells from different LNP mRNA vaccination groups after co-culture with target cells (n = 5). c, Cytokine secretion of T cells co-cultured with target cells for 18 hours (n = 5). The secreted cytokines in media were measured by beads-based immunoassays (seen methods). Target cell alone showed baseline levels of cytokines in media. Additional cytokines, such as IL-2 and IL-12 were added to media to maintain effector function of T cells. All statistics were derived from Dunnett’s multiple comparison test between HPV16 E6 + E7 and other treatment groups. PMA/Ionomycin group was excluded from comparisons. Sample number of vaccination groups is 5, except for PMA/Ionomycin and target cell. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Dunnett’s comparison test was used to determine statistical significance between WT antigens and modified antigen groups. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001. Panel a and insets in b and c created with BioRender.com.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Fang, Z., Monteiro, V.S., Oh, C. et al. A modular vaccine platform for optimized lipid nanoparticle mRNA immunogenicity. Nat. Biomed. Eng (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41551-025-01478-6

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41551-025-01478-6