Introduction

Bacterial infections continue to be a significant worldwide health concern, affecting high morbidity, mortality, and economic burden1. There is an urgent need to advance novel antibiotic compounds and innovative approaches to address human health disorders. Chemically derived pharmaceuticals are allied with numerous adverse effects, as well as the escalating concern of antimicrobial resistance. Consequently, there is a growing interest in assessing medicinal plants owing to their widespread availability and lack of toxicity for medical treatment, along with their efficacy in combating pathogenic microorganism infections and various human health conditions2,3,4. The AgNPs have attracted significant attention within the scientific community, primarily because of their remarkable characteristics such as conductivity, catalytic activity, stability, and antimicrobial effects. The notable antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anticancer properties exhibited by AgNPs augment their therapeutic efficacy and position them as favorable contenders for various biomedical uses5,6. Although various methods exist to produce nanoparticles (NPs) involving hazardous materials, high pressure, and energy-intensive processes like pyrolysis, laser ablation, hydro and solvo thermal synthesis and inert gas condensation, there is a growing need for NPs that are more compatible with biological systems. Concurrently, there has been a surge of interest in the biological synthesis of AgNPs, particularly through green synthesis methods utilizing plant extracts. However, plant metabolites such as phenolics, flavonoids, terpenoids, and saponins act as both reducing and stabilizing agents, enabling NP synthesis under mild conditions without toxic waste generation. This resonates with the global trend towards dependable and sustainable approaches to NPs manufacturing7,8. The advancing research on AgNPs unveils their multifaceted and developing functions in the scientific realm, showing the potential to transform numerous sectors, thereby improving healthcare and technology9,10. Following the “biosynthesis” approach, in the present study, we inspected the synthesis of AgNPs using ursolic acid isolated from C. roseus as an efficient and safe method for nanometal production. As far as we aware, this is the first research to disclose the green synthesis of AgNPs using UA isolated from C. roseus as both a reducing and stabilizing agent. Previous reports on plant-mediated AgNPs synthesis have predominantly employed crude extracts containing a complex mixture of phytochemicals, which can lead to variability in NPs size, morphology, and surface chemistry. In contrast, our approach utilizes a single, well-characterized bioactive triterpenoid containing reactive hydroxyl and carboxyl groups, enabling controlled functionalization of the NPs surface and potentially enhancing targeted biological effects. Incorporating UA into AgNPs not only ensures greener synthesis but also imparts intrinsic bioactivity, potentially producing multifunctional nanomaterials with enhanced therapeutic performance. The isolation, characterization, and identification of ursolic acid from C. roseus were previously described by Kamatchi et al.11. The aim of the study we report the green synthesis of ursolic acid-mediated AgNPs and evaluate their antibacterial, antibiofilm, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anticancer potentials. The NPs were extensively characterized using spectroscopic, microscopic, and diffraction techniques. Further, we investigated there in vitro cytotoxicity on cancer and normal cell lines, oxidative stress modulation in yeast models, and potential molecular interactions through in silico docking studies. This work highlights the multifunctional properties of UA-AgNPs and lays the groundwork for future in vivo and pharmacokinetic evaluations.

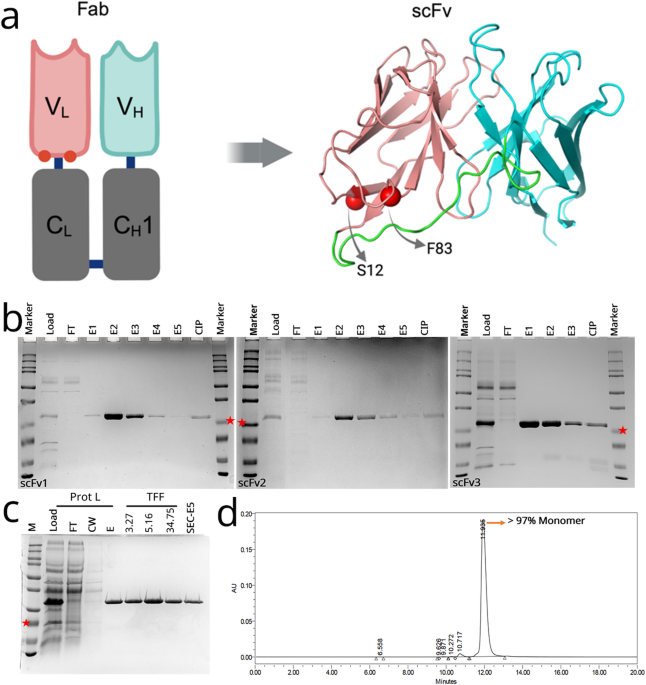

Materials and methods

Materials

Pathogenic microbial strains were gained from the Microbial Culture Collection Center, Department of Microbiology, Periyar University, Salem, Tamil Nadu. Bacterial strains were cultured on Mueller-Hinton Agar at 27 ± 2 °C with 180 rpm shaking for 12 h. The HeLa and Vero cell lines were procured from NCCS, Pune, and handled following institutional biosafety and national ethical guidelines. As only established cell lines were used, ethics approval was not required12. All media and chemicals were sourced from Hi-Media and Sigma-Aldrich (India). UA-AgNPs synthesis, handling, and disposal followed institutional nanomaterial safety protocols in a Class II biosafety cabinet with PPE, adhering to OECD nanomaterial guidelines.

Biosynthesis of AgNPs

The ursolic acid solution was prepared by dissolving 2.5 g of the compound in 25 mL distilled water and adding methanol in a 250 mL Erlenmeyer flask. The mixture was heated at 50 °C for 15 min with stirring, then filtered through Whatman No. 1 paper and stored at 4 °C. For green synthesis of AgNPs, 10 mL of ursolic acid solution was mixed with 90 mL of 3 mM AgNO3 (1:9 ratio) and heated at 50 °C for 3 h with constant agitation. Formation of UA-AgNPs was confirmed by a color change from pale yellow to dark brown. The pellet was dehydrated at 50 °C for 24 h and desiccated at 27 ± 2 °C for surface and biological analyses13.

Surface characterization of AgNPs

Various instrumental methods were used to characterize the biosynthesized UA-AgNPs to determine their morphological, structural, optical, elemental, size, and physicochemical properties. A UV-Vis spectrophotometer (UV-1800, Shimadzu, Japan) in the 200–800 nm range was primarily employed to confirm NPs in the solution mixture at room temperature with a 1 cm quartz cuvette. In addition, using XRD (X-ray diffraction) analysis (Shimadzu, XRD-6000, Japan), the crystalline integrity of NPs was evaluated. The functional components of the plant extracts and NPs were identified using the FT-IR spectrum (Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy) (Bruker alpha, Ettlingen, Germany). The spectral range of the sample was kept constant at 4000–400 cm− 1 with 4 cm− 1 resolution, using the KBr pellet method. The EDX (Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy) was used to investigate the elemental configuration of the NPs, operating at 15 kV, with elemental mapping performed over an average acquisition time of 60 s per spot. Furthermore, the size and shape of the NPs were analyzed using a Hitachi H-800 TEM (Transmission electron microscopy). A DLS (Dynamic light scattering) and zeta potential were measured at 25 ± 1 °C with a 90º scattering angle (Malvern Zetasizer Nano-ZS). Samples were diluted 1:10 in deionized water to minimize multiple scattering, and each run included three consecutive measurements (60 s acquisition time).

Analysis of anti-microbial sensitivity

The antibacterial activity of biosynthesized UA-AgNPs was assessed against Gram-positive (Bacillus cereus ATCC11778, Enterococcus faecalis ATCC19433, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC25923) and Gram-negative (Escherichia coli ATCC25922, Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC4352, Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC25668) pathogens by the agar well diffusion method. Each bacterial culture (OD600 = 0.4) was spread on Mueller-Hinton Agar using a cotton swab, and 8 mm wells were filled with 50 µL (1 mg/mL) of UA-AgNPs, AgNO3, ursolic acid, DMSO (2%), vancomycin, or gentamicin (10 µg/mL). Vancomycin and gentamicin served as positive controls, while 5% DMSO acted as a negative control. After a 24 h aerobic incubation period at 37 °C, the plates were photographed, and inhibition zones were measured in millimeters. All assays were performed in triplicate14.

Determination of bacteriostatic and bactericidal effect

The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of UA-AgNPs was calculated by the broth microdilution method following CLSI guidelines15. Serial two-fold dilutions of UA-AgNPs (3.125–400 µg/mL) in 190 µL Mueller-Hinton Broth were prepared in microtiter wells and inoculated with 10 µL of bacterial suspension (1 × 106 CFU/mL). After 24 h incubation at 37 °C, bacterial growth inhibition was measured at 600 nm using a microplate reader, and the lowermost concentration displaying no visible growth was recorded as the MIC (IC50). For Minimum Bactericidal Concentration (MBC) determination, 5 µL from each well was streaked on MHA and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. The lowermost concentration with fewer than 5 CFU or no visible colonies was considered the MBC. All tests were done in triplicate, and findings were presented as mean ± standard deviation.

Time kill assay

A kinetic change in the antibacterial activity of UA-AgNPs was determined in microplates using an MHB medium with an inoculum of 1 × 106 CFU/mL. The standard bacterial suspension was treated with UA-AgNPs at the final value of MIC at 0 h for each bacterial species in the total final volume of 2 mL. The experiment will last up to 10 h. All culture tubes were incubated aerobically at 37 °C in a shaking incubator at 150 rpm. The viability of bacterial cell was calculated spectrophotometrically using a spectrophotometer (UV/Vis 1800, Shimadzu). The experiment was carried out in triplicate16.

Biofilm Inhibition assay

Biofilm inhibition was evaluated in 96-well plates (polystyrene microtiter). Each well received 190 µL of MHB and 10 µL of bacterial suspension (OD600 = 1.0) with 0.5% glucose to induce biofilm formation, followed by incubation at 37 °C for 24 h. The MHB alone served as the negative control. After incubation, wells were washed with sterile phosphate saline to remove non-adherent cells, and fresh MHB containing UA-AgNPs at MIC concentration was added. Plates were reincubated at 37 °C for 24 h, washed twice with phosphate saline (pH 7.2), air-dried for 30 min, and fixed with 200 µL of 2% sodium acetate. Biofilms were stained with 0.1% crystal violet for 30 min in the dark, rinsed thrice, air-dried at 25 ± 2 °C for 1 h, and solubilized in 200 µL of 33% glacial acetic acid. Then, 125 µL of the solution was relocated to a new plate, and absorbance was measured at 570 nm17. All assays were performed in triplicate, and biofilm inhibition (%) was determined accordingly.

$$:text{%}:text{b}text{i}text{o}text{f}text{i}text{l}text{m}:text{i}text{n}text{h}text{i}text{b}text{i}text{t}text{i}text{o}text{n}:=:text{O}text{D}:text{g}text{r}text{o}text{w}text{t}text{h}:text{c}text{o}text{n}text{t}text{r}text{o}text{l}:-:text{O}text{D}:text{s}text{a}text{m}text{p}text{l}text{e}:text{O}text{D}:text{g}text{r}text{o}text{w}text{t}text{h}:text{c}text{o}text{n}text{t}text{r}text{o}text{l}:text{x}:100$$

Mobility activity

The efficacy of the swimming and swarming motility tests was assessed on human pathogenic microorganisms. Individual bacterial cultures were seeded into the agar plate center for the swimming test; nutritional agar was used to make the plates, both in the presence and absence of UA-AgNPs. After that, the plates were incubated for 24 h at 30 °C, the post-inoculation period the clear zone was measured (diameters) caused by bacterial migration.

A semi-solid agar was set for the presence and absence of biosynthesized UA-AgNPs for the swarming motility test. About 5 µL of bacterial cultures were identified in the middle of the agar plate. After that, plates were incubated at 30 °C for 24 h while upright. Subsequently, the motility of live bacterial cultures across the agar plate surface was observed and compared with control plates. In both assays, the plates created without UA-AgNPs were used as the control18.

Assessment of membrane integrity

The intracellular protein and nucleic acid (DNA) leakage experiment was conducted as per the Arunachalam et al.19 protocol. A total of 3 mL aliquots of 12 h grown in each bacterial cell culture were collected by centrifugation for 15 min at 5000 rpm. The pellets were splashed thrice and re-suspended in 5 mL of PBS (pH 7.4). Each bacterial culture was treated with UA-AgNPs at optimal MIC concentrations and incubated at 37 °C. After adding UA-AgNPs to the bacterial solution, we collected the supernatant and examined the absorbance at 260 and 595 nm with a UV-visible spectrophotometer every 1 h for 8 h. The experiment was conducted three times to validate the results.

2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) assay

The DPPH assay for UA-AgNPs was achieved according to the earlier report by Raguvaran et al.20, and the following equation calculate the scavenging activity (%):

$$:text{%}:text{R}text{a}text{d}text{i}text{c}text{a}text{l}:text{s}text{c}text{a}text{v}text{e}text{n}text{g}text{i}text{n}text{g}:text{p}text{o}text{t}text{e}text{n}text{t}text{i}text{a}text{l}=frac{{text{C}text{o}text{n}text{t}text{r}text{o}text{l}}_{text{A}text{b}text{s}}-{text{S}text{a}text{m}text{p}text{l}text{e}}_{text{A}text{b}text{s}}}{{text{C}text{o}text{n}text{t}text{r}text{o}text{l}}_{text{A}text{b}text{s}}}:times:100$$

Where Control (Abs) and Sample (Abs) are the absorbance of the control (blank, without UA-AgNPs) and the sample, respectively.

Ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) assay

The FRAP radical scavenging assay for UA-AgNPs was executed as stated by Khuda et al.21. The scavenging % was determined as follows:

$$:text{%}:text{R}text{a}text{d}text{i}text{c}text{a}text{l}:text{s}text{c}text{a}text{v}text{e}text{n}text{g}text{i}text{n}text{g}:text{p}text{o}text{t}text{e}text{n}text{t}text{i}text{a}text{l}=frac{{text{C}text{o}text{n}text{t}text{r}text{o}text{l}}_{text{A}text{b}text{s}}-{text{S}text{a}text{m}text{p}text{l}text{e}}_{text{A}text{b}text{s}}}{{text{C}text{o}text{n}text{t}text{r}text{o}text{l}}_{text{A}text{b}text{s}}}:times:100$$

Where Control (Abs) is the absorbance of the control (blank, without AgNPs) and Sample (Abs) is the absorbance in the presence of the UA-AgNPs. The antiradical activity is then expressed by the IC50 value, where IC50 dose required to find 50% of the reduced form of the DPPH and FRAP radical. Ascorbic acid was used as standard for antioxidant analysis.

Effect of UA-AgNPs in yeast mutant strains

The Yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) antioxidant assays were included to complement chemical assays (DPPH and FRAP), providing a cellular model to assess the ability of UA-AgNPs to mitigate oxidative stress. A yeast (S. cerevisiae, BY4741, wild-type, mutant) culture that was growing exponentially (around 1 × 105 cells) was treated with UA-AgNPs (100 µg/mL) on a microwell plate with 3 mM of H2O2. The final volume was increased to 200 µL using yeast peptone dextrose broth. After an 18 h incubation period at 30 °C, the culture was serially diluted and spread onto yeast extract peptone dextrose agar. Then the plates were incubated at 30 °C for two days, and CFUs were recorded. The percentage of CFU represented the viability22.

Anticancer activity

The anti-proliferation effect of UA-AgNPs and control group cells was evaluated against human cancer cell lines (HeLa cells) using a 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazolyl-2)−2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay23. Cells of optimum density (1 × 106 cells/well) were seeded into a 96-well plate for 12 h and then treated with varying concentrations of UA-AgNPs (0, 0.78, 1.56, 3.12, 6.25, 12.5, 25, 50, 100, and 200 µg/mL) for 24 h. A blank well contains 100 µL of Dulbecco’s modified Eagle media without cells. After 24 h of treatment, the culture medium was discarded, and 100 µL of MTT solution (0.2 mg/mL in PBS) was added to each well. The plates were incubated for 3 h at 37 °C. The resulting formazan crystals were quantified using a microplate at 570 nm. Paclitaxel served as the positive control in this experiment. The growth inhibition (%) was computed as follows:

$$:text{P}text{e}text{r}text{c}text{e}text{n}text{t}text{a}text{g}text{e}:text{o}text{f}:text{v}text{i}text{a}text{b}text{i}text{l}text{i}text{t}text{y}=frac{text{O}text{D}:text{o}text{f}:text{c}text{o}text{n}text{t}text{r}text{o}text{l}-text{O}text{D}:text{o}text{f}:text{t}text{e}text{s}text{t}}{text{O}text{D}:text{o}text{f}:text{c}text{o}text{n}text{t}text{r}text{o}text{l}}:text{x}:100$$

Determination of apoptotic morphological changes

Using ethidium bromide (EBr) and acrid orange (AO) staining techniques, apoptosis cell validation was determined. Cells were sowed at 1 × 106 cells/well for 24 h after being treated with AgNPs. The cells were treated with methanol: glacial acetic acid (3:1) for 30 min at 4 °C. Afterward, cells were washed two times with PBS solution, then subjected to AO/EBr (1:1 ratio) staining at 37 °C for 30 min. After incubation, cell samples were photographed using a FLoid cell imaging station (Invitrogen, USA) and subsequently washed three times with PBS. The total cell count in each field was determined by identifying and counting cells that displayed apoptotic characteristics24.

Cytotoxic activity

The cytotoxicity activity of UA-AgNPs on Vero cells was calculated using the MTT test25. Vero cells were introduced at a density of 1 × 104 per well onto 96-well plates in EMEM with Earle’s saline culture media with 5% CO2 at 37 °C for 24 h. For the following incubation, the cells were treated with five doses of the UA-AgNPs (6.25, 12.5, 25, 50, 100, and 200 µg/mL). Aliquots of 10 µL of filtered (0.22 μm) MTT (0.5 mg/mL) dissolved in PBS were poured into wells, and the plates were incubated in the dark for 4 h at 37 °C in a humidified environment with 5% CO2. The supernatants were discarded, and 100 µL of DMSO was added. The plates were simultaneously stirred for 15 min, and the OD was determined at 570 nm. The cell viability (%) was calculated as follows:

$${text{Cell viability (% ) = Mean OD/Control OD x 100% }}$$

Estimation of nitric oxide (NO) production

Nitric oxide (NO) is a key bio-regulation molecule in the nervous, immune, and cardiovascular systems. RAW 264.7 cells (1ᵡ105 cells/mL) of macrophages were prefixed with different doses of UA-AgNPs for 30 min. Then, cells were triggered for 24 h, either with or without lipopolysaccharide (1 µg/mL) at 37 °C with 5% CO2. A total of 100 µL of culture supernatant in each well was assorted with Griess reagents; this mixture allowed for the measurement of the NO level in the culture supernatants. Then, the mixture was incubated at 27 ± 2 °C for 15 min in the dark. The absorbance was read at 540 nm to determine the concentration of NO; sodium nitrite served as standard in this experiment26.

In Silico molecular Docking

A popular analytical technique for matching two molecules, such as protein-ligand or protein-protein, is molecular docking. The current study confirms biosynthesized UA-AgNPs of AgNO3 based on the particle’s crystal structure (XRD) and size (TEM). In addition, AgNO3 (ligand) was docked with pathogenic bacterial proteins, Pro-elastase protein (LasB) from Pseudomonas and Hemolysin BL lytic component L1 (HblL1) from Bacillus, respectively. The direct molecular docking of whole NPs is not computationally feasible due to their complex, multi-atomic structures, heterogeneous surfaces, and dynamic nature in biological environments. To address this, we used AgNO3 as a simplified ligand model to represent the reactive silver species present on the surface of UA-AgNPs. While this approach cannot fully replicate the complete physicochemical interactions of intact UA-AgNPs, which also involve the ursolic acid capping layer and possible adsorbed biomolecules, it provides qualitative insight into potential silver-protein interaction sites and binding affinities. The protein data bank (PDB) provided the 3D structure of bacterial protein molecules (receptor) (P. aeruginosa, 8CR7, and B. cereus, PDB IB: 7NMQ). In addition, proteins from breast cancer (MCF7) were chosen for their pathogenicity. The human vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR 2) and its 3D structure were saved from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) (ID: 3V6B). Meanwhile, LasB (P. aeruginosa elastase) is a virulence factor linked to tissue damage and biofilms. HblL1 (B. cereus hemolysin) is a pore-forming toxin contributing to pathogenicity. VEGFR2 regulates angiogenesis and tumor growth, making it an anticancer target. These proteins were chosen to reflect both antibacterial and anticancer relevance of UA-AgNPs. The 3D structure of the AgNO3 was generated using VESTA (ver.3.5.8, www.jpminerals.org). The ligands and proteins employed in this investigation were docked according to their pathogenicity levels. AutoDock 4.2 performed molecular docking of ligands with specified protein targets, applying a Lamarckian genetic algorithm. AutoDock 4.2 created the protein by eliminating water molecules, adding polar hydrogen bonds, and allocating Kollman charges. The ligands were adjusted for torsion angles, and a docking grid of 12Å × 12Å × 12Å was produced. The possible binding sites, binding energy, Van der Waals, number of hydrogen bonds formed, their distance, and amino acid residues involved were examined and determined to be important using the BIOVIA Discovery Studio Visualizer.

Statistical analysis

The experimental data were presented as the mean ± SD (standard deviation) of three replicates. We submitted the data to one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) where relevant and calculated r2 (regression) values using SPSS 21.0. Tukey’s multiple range tests (p ≤ 0.05) were used to conclude statistical significance between the control and treatment groups27.

Results and discussion

Green synthesis of AgNPs

The concept of phyto-nanotechnology (green synthesis) involves synthesizing NPs from plant metabolites that are compatible with biological systems, readily available raw materials, and highly stable. In this approach, plant molecules act as reducing, stabilizing, and capping agents for the synthesis of AgNPs. Beyond their scientific relevance, plants also serve as sustainable resources for greener biomaterials, offering eco-friendly alternatives to conventional practices such as burning agricultural waste, which contributes to air pollution28. Green synthesis of AgNPs has attracted considerable interest because it avoids the hazardous by-products commonly associated with chemical synthesis. Conventional methods such as hydrothermal or solvothermal synthesis, pyrolysis, or laser ablation often require toxic chemicals, high pressure, or energy-intensive conditions. In contrast, plant-mediated routes provide safer, faster, and more sustainable NPs production29. In this study, the ursolic acid solution was mixed with an AgNO3 solution, which caused the reduction of metal ions (Ag+) into atoms (Ag0) and formed stable NPs. The color change indicated the production of AgNPs30. The synthesis of AgNPs was performed starting from 90 mL of 3.0 mM AgNO3 solution mixed with 10 mL of ursolic acid solution along with 1 mL of methanol with a constant stirrer at 50 °C for a 3 h incubation period and pH at initiation 8, which showed a good productivity protocol for UA-AgNPs synthesis. In general, the biosynthesis of metal NPs utilizing plant extracts consists of three main stages, which begin with an ion reduction process that indications to cluster formation and then prompts the growth of NPs31. The chemical synthesis of AgNPs poses a crucial risk associated with this method: creating hazardous by-products. Guzman et al.32 state that the biogenic production of NPs is considered a substitute strategy for the inherent drawbacks associated with using chemicals. Moreover, utilizing plant metabolites in NP synthesis offers advantages over other biological materials like plants, fungi, and bacteria, with significantly faster synthesis kinetics33.

UV-Vis spectrophotometer analysis

The green synthesized UA-AgNPs may be employed for their intended purpose, but certain techniques must be used to confirm their formation. UV-visible spectroscopy is the most effective technique used for the surface characterization of NPs. In this current study, the production of UA-AgNPs was definite by the appearance of a single, strong, and broad surface plasmon resonance (SPR) electron peak at 440 nm, as determined by a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Fig. 1). According to Prathna et al.34, smaller average size and a high dose of AgNPs are linked to the obtained maximum of lower and higher wavelength (λmax) values, respectively. The SPR pattern depends on the characteristics of the metal particles, creating an electric field and causing them to resonate in the liquid medium used for synthesis and the inter NPs coupling interactions35. The UA-AgNPs exhibited a strong SPR peak at 440 nm, whereas previous reports using Origanum vulgare extract observed a peak at 430 nm, reflecting differences in phytochemical composition and NPs size distribution36.

FT-IR analysis

FT-IR spectroscopy can help track biomolecules that influence NPs formation while using plant biomolecules. The FT-IR spectrum of ursolic acid-mediated NPs exhibits several absorption peaks at different locations, including at 3209.70 cm− 1 (O-H stretch of hydroxyl group), 2929.85 cm− 1 (C-H stretching of alkane), 2319.40 cm− 1 (C ≡ O stretch), 1604.47 cm− 1 (C ≡ O stretch of carboxyl group), 1317.16 cm− 1 (C-F stretch), 1010.44 cm− 1 (C = O stretch of ester group), 820.14 cm− 1 and 591.04 cm− 1 (C-Cl or C-Br starch of Alkyl halides), which are associated with the several oxygen-containing functional groups (carboxyl and ester groups) that may help stabilize the process and prevent aggregation; furthermore, they participate in reducing metal ions in the NPs (Fig. 2). A comparison with the FT-IR spectrum of ursolic acid, as reported by Kamachi et al.11. The spectrum of ursolic acid displays characteristic peaks at 3431 cm⁻¹ (O-H stretch vibrations), 2929 cm⁻¹ and 2862 cm⁻¹ (C-H stretch of alkanes), 1689 cm⁻¹ (C = O stretch of carboxyl groups), 1458 cm⁻¹ and 1377 cm⁻¹ (C-H bending vibrations), 1280 cm⁻¹, 1244 cm⁻¹, 1182 cm⁻¹, 1195 cm⁻¹, and 1135 cm⁻¹ (various C-O and C-C stretch vibrations), 1035 cm⁻¹ (C-O stretch), 991 cm⁻¹ and 958 cm⁻¹ (out-of-plane C-H bending), and 827 cm⁻¹ and 755 cm⁻¹ (C-H bending of aromatic groups or alkyl halides). The shifts in peak positions from ursolic acid to AgNPs suggest that functional moieties for example hydroxyl (O-H) and carboxyl (C = O) groups are actively involved in reducing silver ions, while ester and alkyl halide groups put up to capping and stabilization through surface adsorption of the NPs. The presence of new peaks or changes in intensities further supports the chemical modifications that occur during NPs formation. Plants serve as abundant reservoirs of diverse biologically active compounds and secondary metabolites. The existence of hydroxyl groups (OH) within plant molecules, including amino acids, enzymes, proteins, carbohydrates, alkaloids, flavonoids, and phenolic substances, plays a crucial role in the stabilization and conversion of silver ions (Ag+) to Ag0, as discussed by Bawazeer et al.37. The subsequent reduction to Ag+ initiates the generation of silver nuclei, leading to AgNPs forming, as Li et al. highlighted38. The hydroxyl and carboxyl groups facilitate the reduction of Ag+ to Ag0, while its hydrophobic pentacyclic triterpenoid backbone provides steric stabilization to prevent NPs aggregation and contributes to uniform morphology39,40.

XRD analysis

The XRD configuration of the UA-AgNPs exhibited numerous sharp and intense peaks (Fig. 3), serving not only to confirm the crystallinity of the UA-AgNPs but also to validate the formation of AgNPs. The fundamental principle underlying XRD analysis is Bragg’s law, which aids in determining the Bragg reflection of AgNPs. The outcomes depicted in the study demonstrate that AgNPs have been successfully synthesized, aligning with the JCPDS (893722) database, and the average crystallite size (14.8 nm) was determined using the Debye-Scherrer calculation. In addition to the distinctive peaks of face-centered cubic (fcc) silver, the diffractogram exhibits several intense peaks that are yet to be identified in Fig. 3. It is postulated that these unidentified peaks stem from the crystallization of the bioorganic layer on the surface of the AgNPs, as suggested by Priya et al.41.

EDX analysis

The elemental constituents of the green synthesized UA-AgNPs were obtained from EDX analysis, as displayed in Fig. 4a. The obtained EDX analysis exemplified a strong silver signal in the (ursolic acid + AgNO3) sample at 3 keV, validating the presence of AgNPs with a silver weight of 80.47%. Meanwhile, EDX analysis showed the relative composition of elements like carbon (C-12.9%) and copper (Cu-6.63%), likely from phytoconstituents (capping agents) on the AgNPs surface, indicating silver ion reduction to elemental silver42. Additionally, a hydration layer observed in the EDX analysis is linked to the surface properties and synthesis method. Plant-derived metabolites coat the NPs in green synthesis, retaining water molecules and forming this layer. This coating stabilizes the NPs, influences their surface charge, and enhances biocompatibility, which is crucial for applications involving biological systems, as it mimics physiological conditions43.

TEM analysis

TEM may be used to measure the green-mediated NPs quantitatively in terms of their shape, size distribution, and particle size. Additionally, TEM offers better spatial resolution than SEM and permits a deeper examination of NPs. In the present study, the ursolic acid-mediated NPs are polydisperse with an average size of 15.55 nm (Fig. 4b & c) and have a predominantly spherical morphology with occasional aggregation. The polydispersity was attributed to the natural variability of phytochemical-mediated reduction. Generally, the AgNPs are well dispersed, even though some of them were seen to be agglomerated. The antibacterial properties of silver have increased due to the advancement of nanomaterials with sizes in the nano range. The potential bactericidal activity against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria was confirmed by synthesizing AgNPs with sizes ranging from 10 to 100 nm. Due to their small size, enabling easy penetration of microbial cell walls, the biological effects of AgNPs, including antibacterial and cytotoxic activities, are intricately linked to their size and shape, as discussed in several studies44.

(a) Elemental mapping of biosynthesized UA-AgNPs; (b) TEM visualization of UA-AgNPs and their size distribution; (c) Histogram representation of the UA-AgNPs.

DLS and zeta potential

The size distribution, polydispersity index (PDI), effective surface charge, and stability of the green synthesized UA-AgNPs were evaluated using DLS and zeta potential techniques. The size distribution profile displayed an average particle size of approximately 129 nm for the synthesized AgNPs with a minimal PDI of 0.32 (Fig. 5a), while the zeta potential was noted at −0.32 mV to colloidal stability (Fig. 5b). The measured zeta potential of −0.32 mV appears low for colloidal stability. However, the UA-AgNPs remained well-dispersed for several weeks without visible aggregation, suggesting stabilization by the ursolic acid capping layer rather than by electrostatic repulsion. The TEM revealed a mean particle size of 15.55 nm, representing the dry core size. In contrast, DLS measured a larger hydrodynamic diameter of approximately 129 nm, attributed to the surrounding hydration layer and capping molecules derived from ursolic acid. This results in a generally larger size compared to that obtained from TEM analysis. The presence of the hydration shell increases the apparent size in solution and reflects the NPs behavior in biological environments. A particle size under 150 nm and PDI values nearing 0.3 are appropriate for cellular acceptance. The zeta potential analysis evaluates the surface charge of NPs in colloidal suspensions by measuring the potential difference between the dispersion medium and the fluid layer attached to the particles. It is essential for assessing NPs stability, surface properties, and interaction potential in various environments. This study obtained a negative zeta potential value, confirming that it helps prevent aggregation, ensuring better dispersion and enhanced effectiveness in applications including antibacterial activity45. The surface charge stands out as a critical attribute influencing the ability of NPs to interact with macromolecules on cellular surfaces or within cells. Past studies by Shrestha et al.46 indicate that a higher positive or negative charges in particles leads to repulsion and contributes to stable particles with minimal aggregation tendencies. Furthermore, the effective surface charge of NPs may be impacted by the solution’s pH level, potentially resulting in a zero isoelectric point or effective surface charge at a specific pH47. Additionally, the negative charge of particles tends to promote particle stability by impeding aggregation processes48.

(a) Particle size intensity distribution of UA-AgNPs via DLS; (b) Zeta potential measurements of UA-AgNPs.

Antibacterial activity

Recently, biosynthesized AgNPs have emerged as promising biocompatible nanoscale components for innovative antibacterial uses. The antibacterial properties of UA-AgNPs were assessed against gram-negative and positive human pathogenic microbes using the well diffusion method; the results are displayed in Fig. 6and Table 1. The standard antibiotics, including vancomycin, gentamicin (positive control), AgNO3, ursolic acid, and DMSO (negative control), were also separately analyzed for bactericidal activity to compare their activity with UA-AgNPs. The antibacterial assay results indicated that the phyto-synthesized UA-AgNPs exhibited strong antibacterial activity efficacy against all test pathogens compared to the control and negative control. Meanwhile, UA-AgNPs exhibit significant antibacterial activity as compared to the positive control. The maximum inhibition zones of UA-AgNPs achieved against B. cereus and P. aeruginosa were 18.00 and 16 ± 0.3 mm, respectively. In Gram-positive bacteria, the NPs interact with the thick peptidoglycan layer, creating pores and weakening structural integrity, which facilitates leakage of cellular contents. In Gram-negative bacteria, UA-AgNPs penetrate the thinner peptidoglycan layer and outer membrane containing lipopolysaccharides, causing destabilization and increased permeability. In both cases, silver ions released from UA-AgNPs bind to membrane proteins and phospholipids, further compromising barrier function and promoting protein/DNA leakage. Meanwhile, AgNO3 exhibits moderate antibacterial activity but is also associated with environmental toxicity. Coupling silver ions with biomolecules can mitigate its impact on pharmaceutical applications. This strategy reduces toxicity and enhances biocompatibility, making it more suitable for therapeutic use49. Furthermore, the inherent biological activity of ursolic acid can improve the pharmacological potential of UA-AgNPs, providing a synergistic advantage in applications like antimicrobial therapies. The antibacterial activity of UA-AgNPs can be attributed to multiple complementary mechanisms influenced by their nanoscale size (15.55 nm average, TEM diameter) and surface characteristics (negative zeta potential, −0.32 mV). The small particle size enhances penetration through bacterial cell walls, enabling direct interaction with intracellular targets. The negative surface charge promotes electrostatic interaction with positively charged regions on microbial membranes, causing membrane destabilization and increased permeability. These interactions lead to leakage of cytoplasmic contents, disruption of respiratory chain enzymes, and interference with DNA replication. The ursolic acid capping layer further contributes bioactive functional groups (hydroxyl and carboxyl) that potentiate antibacterial effects via oxidative stress induction and inhibition of cell wall synthesis. The combined impact of these size- and surface-dependent mechanisms accounts for the superior activity observed compared to AgNO3 alone, and in some cases was comparable to standard antibiotics (vancomycin and gentamicin)50,51. This highlights the antibacterial efficacy of AgNPs, positioning UA-AgNPs as a promising alternative or complementary strategy to conventional antibiotics.

Bacteriostatic and bactericidal effect

The MBC/MIC ratio serves as an indicator of the bactericidal effectiveness of specific biomolecules or NPs. These assessments contributed to assessing the antimicrobial efficacy of UA-AgNPs across a range of concentrations for a set duration under favorable bacterial growth conditions. The bacteriostatic and bactericidal effects of biosynthesized UA-AgNPs have been screened by determining MIC and MBC against B. cereus and P. aeruginosa. In these experiments, AgNPs showed potent antibacterial activity with MIC concentrations of 6.95 and 12.39 µg/mL and MBC concentrations of 50 µg/mL against B. cereus and P. aeruginosa, respectively (Fig. 7). The findings demonstrated remarkable antibacterial efficacy even at low UA-AgNPs concentrations, suggesting a correlation between bacterial growth inhibitions and increasing UA-AgNPs concentrations. Theoretically, a bactericidal drug is preferable since it kills bacteria, which should speed up the eradication of the infection, enhance clinical results, and lessen the chance that resistance will develop during the spread of the disease. Resistance mutations that might arise due to antibiotic resistance are removed if organisms are killed rather than inhibited52.

Time kills trials

Bacterial infections are caused mainly by their quick reproductive time. However, the bacterium’s reproduction time may be a suitable method to avoid viable infection since AgNPs successfully suppressed and killed the bacteria in a dosage and exposure time, as revealed in the time-kill trials53. A Time-killing curve analysis was carried out to observe bacterial growth spectrum under UA-AgNPs influence and changes in bacterial optical density (OD600), as depicted in Fig. 8. At a MIC concentration of 6.95 µg/mL, B. cereus was inhibited for 4 h, and P. aeruginosa (12.39 µg/mL) was inhibited for 6 h. In this study, control strains exhibited a progressively increasing growth pattern at every 1 h incubation, suggesting membrane disruption and oxidative stress as primary modes of action. The time-kill curve test enabled the monitoring of AgNPs antimicrobial effectiveness over time concerning bacterial growth stages such as lag, exponential, and stationary. The growth curves of bacteria exposed to AgNPs showed that they may suppress the development and reproduction of both bacteria. The efficiency of AgNPs in killing bacteria was determined by the decrease in colony-forming units, also known as bactericidal activity. In the present study, in vitro antimicrobial data demonstrate that UA-AgNPs quickly increased bactericidal impact on B. cereus and P. aeruginosa at doses equal to or more than the MIC.

Inhibition of biofilm production

The biofilm is created by a colony of microorganisms adhering to a surface and by synthesizing and secreting exopolysaccharides (EPS). Biofilms present a significant hazard in various industries, notably healthcare and food. It has been discovered in recent years that NPs can exhibit strong anti-biofilm properties by selectively focusing on many biofilm development stages54. In the current study, the in vitro anti-biofilm assay of UA-AgNPs was evaluated against the biofilm-producing bacteria B. cereus and P. aeruginosa, resulting in inhibition of 64.43% and 60.89%, respectively (Fig. 9). It has been shown that UA-AgNPs are more effective against cell adhesion and biofilm colonization. In the biofilm analysis, the significant reduction in biomass implies interference with bacterial adhesion and extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) synthesis, likely due to UA-mediated inhibition of quorum-sensing pathways. The results obtained from MIC, MBC, and biofilm formation assays propose that the Gram-negative bacteria (P. aeruginosa) are more resistant to biosynthesized NPs than the Gram-positive bacteria (B. cereus). Potential applications of UA-AgNPs in treating infections caused by highly antibiotic-resistant biofilms are being explored55. The obtained results support that the green-synthesized AgNPs electrostatically interact with cells to disrupt biofilm development, target eDNA to degrade EPS production, suppress bacterial signaling to prevent biofilm formation, and engage with extracellular proteins and small regulatory RNAs to inhibit biofilm formation56,57.

UA-AgNPs impact on biofilm formation in selected bacterial cultures (B. cereus and P. aeruginosa). Distinct superscript letters (a, ab, b, etc.) within the same column denote statistically significant differences among the treatment groups (p < 0.05) according to Tukey’s multiple range test. Groups bearing the same letter do not differ significantly from one another..

Swarming and swimming mobility

Bacterial mobility, regulated by quorum sensing, function as a virulence factor that contributes significantly to pathogenicity by involving host-cell adhesion, colonization, and biofilm formation. Biofilm production is facilitated by flagella-mediated motility, swarming, and swimming factors58. The migratory ability of B. cereus and P. aeruginosa over swimming (74% and 67%) and swarming (79% and 71%) agar plates was successfully inhibited by UA-AgNPs presented in Figs. 10 (a) and (b). The MIC concentrations of 6.95 and 12.39 µg/mL reduced B. cereus and P. aeruginosa growth and motility relative to the control plate, respectively. This might be due to AgNPs negatively regulating flagella formation and assembly genes. Inhibition of bacterial motility further supports the hypothesis that UA-AgNPs impair flagellar function and energy-dependent surface movement, thereby limiting colonization and biofilm maturation59. Meanwhile, the anti-swimming and swarming properties of UA-AgNPs may limit B. cereus and P. aeruginosa ability to build drug resistance by forming biofilms. While MIC values confirm inhibition of planktonic bacterial growth, motility and biofilm assays show that UA-AgNPs also impair colonization and biofilm protection, making bacteria more susceptible to antimicrobial action. This dual antibacterial and anti-biofilm activity suggests their potential for managing wound infections and preventing biofilm formation on medical devices such as catheters, where biofilm-associated resistance is a major clinical concern.

Measurement of cytoplasmic protein and DNA (Deoxyribonucleic acid) leakage

Figures 11(a) and (b) represent the protein and DNA leakage assay results conducted in the presence of ursolic acid-mediated AgNPs against B. cereus and P. aeruginosa. The obtained protein and DNA leakage results revealed that B. cereus and P. aeruginosa showed higher protein and DNA leakage levels at MIC concentrations of 6.95 and 12.39 µg/mL, respectively, compared to the control. After treating with UA-AgNPs for 4 h of incubation, protein and DNA leakage were observed in both bacterial strains. Nevertheless, no leakage of proteins or DNA was observed in the control cells. Subsequent exposure to UA-AgNPs for up to 8 h led to a twofold increase in protein and DNA leakage from the cells. Notably, B. cereus exhibited a relatively higher susceptibility to UA-AgNPs treatment than P. aeruginosa, as evidenced by the elevated levels of protein and nucleic acid release, possibly attributed to variations in cell wall thickness. The leakage of cytoplasmic components like proteins and DNA culminates in bacterial cell death (Fig. 12). The AgNPs may offer a perfect surface within mitochondria, where Ag + ions can interact with DNA and proteins, disrupting their key functions, as proposed by You et al.60. The heightened protein and DNA leakage observed in B. cereus and P. aeruginosa, based on our experimental findings, underscores the potent antibacterial efficacy of UA-AgNPs against these bacterial strains.

Schematic diagram of antibacterial mechanism of biosynthesized UA-AgNPs against human pathogenic bacterial strains.

In vitro antioxidant assay

Antioxidants have gained importance for safeguarding food, medicinal products, and the body against oxidative damage and associated disease processes. Screening for antioxidant properties of plant-derived substances requires methodologies that elucidate the mechanism of antioxidant action61. The DPPH and FRAP activity results of UA-AgNPs at various concentrations are illustrated in Fig. 13 in this study. The NPs displayed neutral radical quenching ability, confirming the antioxidant potential of green-synthesized UA-AgNPs using DPPH and FRAP assays. The significant antioxidant potential of UA-AgNPs was evaluated by DPPH and FRAP radical scavenging assays, which had IC50 of 50.89 and 55.24 µg/mL, respectively. A comparative analysis with ascorbic acid, the standard reference antioxidant, indicates that UA-AgNPs exhibit strong radical scavenging (IC50 − 50.89 µg/mL in DPPH) and reducing power (IC50 − 55.24 µg/mL in FRAP). These values are within the same order of magnitude as reported for ascorbic acid (10–42 µg/mL for DPPH, ˂50 µg/mL for FRAP), highlighting the strong antioxidant potential of UA-AgNPs62,63. The DPPH scavenging activities are acknowledged to be due to the antioxidants hydrogen-donating ability, while FRAP is based on electron transfer rather than hydrogen atom transfer64. Likewise, Keshari et al.65 documented that AgNPs operate as electron donors, allowing them to join with free radicals and convert them into more stable molecules. This, in turn, helps put an end to free radical-producing processes. Our results strongly indicate that UA-AgNPs can serve as potent natural antioxidants, helping to protect health against diverse oxidative stressors linked to degenerative diseases.

In vitro evaluation of the antioxidant activity of UA-AgNPs (a) DPPH (b) FRAP. Values represent mean ± standard deviation of three replicates. Distinct superscript letters (a, ab, b, etc.) within the same column denote statistically significant differences among the treatment groups (p < 0.05) according to Tukey’s multiple range test. Groups bearing the same letter do not differ significantly from one another.

Assessment of antioxidant activity using S. cerevisiae

In vivo experiments were conducted using the BY4741 yeast strain of S. cerevisiae and its wild-type mutant strain. This mutant strain was selected because it is a well-established eukaryotic model for studying low resistance to oxidative treatments, enabling a more accurate assessment of the antioxidant properties of the tested compounds, as noted by Dupont et al.66. While antioxidants may confer beneficial effects on cellular resistance to oxidative stress, certain antioxidants could potentially pose toxicological risks. To evaluate this, green-synthesized UA-AgNPs were introduced during the culture of the BY4741 yeast mutant for 24 h, with the resulting cell concentrations depicted in Fig. 14. In vivo, experiments employing radical scavenging mechanisms in S. cerevisiae wild-type and isogenic deletion strains confirmed the significant in vitro antioxidant activity. The UA-AgNPs also increased the eukaryotic microbe S. cerevisiae resistance to hydrogen peroxide, a superoxide generator. In principle, yeast cells regulate intracellular redox equilibrium via enzymatic and non-enzymatic defense mechanisms. To pinpoint the defense targets of UA-AgNPs in yeast, mutant strains lacking genes (sod1, sod2, gtt2, and ctt1) exhibiting the phenotypes for ROS detoxifying enzymes were used to analyze responses to oxidative stimuli through cell survivability67.

Analysis of antioxidant activity in S. cerevisiae exposed to UA-AgNPs. Sod1 – deficient in cytosolic superoxide dismutase; Sod2 – deficient in mitochondrial superoxide dismutase; Gtt2 – deficient in glutathione S-transferase; Ctt – deficient in catalase. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation of three replicates. Distinct superscript letters (a, ab, b, etc.) within the same column denote statistically significant differences among the treatment groups (p < 0.05) according to Tukey’s multiple range test. Groups bearing the same letter do not differ significantly from one another.

Anticancer activity

The cytotoxicity of biosynthesized UA-AgNPs against malignant cells has been thoroughly documented in recent years, and as a result, these NPs can be used in cancer therapy. The MTT experiment for UA-AgNPs revealed potential anticancer action against the HeLa cell line (Fig. 15a). The UA-AgNPs showed dose-dependent action on HeLa cells, the obtained IC50 value was 29.20 µg/mL. Furthermore, the apoptosis produced in HeLa cells was assessed using the dual staining examination with AO/EtBr. The obtained result provided microscopic confirmation for UA-AgNPs apoptotic properties. AO/EtBr staining differentiates live cell cells, which uniformly bright nuclei, from dead cells, which exhibit orange to red nuclei due to EtBr intercalation with DNA. During apoptosis, chromatin abbreviation and membrane damage lead to an imbalance between deoxyribonuclease activity and the enzymes responsible for maintaining DNA stability68. The outcomes observed from AO/EtBr staining were evident in control cells, exhibiting bright green-fluorescent nuclei and displaying normal cell morphology at 200 µg/mL of UA-AgNPs concentration (Fig. 15b)69. Our results provide preliminary evidence that UA-AgNPs may affect cancer cell viability through mechanisms involving mitochondrial interaction, disruption of the electron transport system, and ROS generation. However, these conclusions are based solely on HeLa cell assays and require confirmation in multiple cancer and normal cell lines, supported by in vivo validation, before establishing therapeutic applicability. This rise in ROS induces oxidative stress, which is identified as the primary mechanism of toxicity70,71. As UA-AgNPs have a large surface area, they can easily penetrate cells and interact with cellular components, disrupting key signaling pathways. This interference with cellular processes contributes to their anticancer effects, as oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction are common mechanisms in cancer cell death72. However, NP-mediated treatment has been used as drug delivery system, as they can direct encapsulated therapeutic agent specifically to diseased cell or tumor tissues73.

(a) Effectiveness of UA-AgNPs in inhibiting cancer cell growth on HeLa cell line; (b) Percentage of growth inhibition. Scale bars: 100 μm.

Cytotoxicity assay on Vero cells

The possible negative impact analysis will investigate the effects of AgNPs produced by plant-mediated processes on human health toxicity, biocompatibility, and interaction with ecosystems. The progress in nanotoxicology and ecotoxicological investigations is essential for formulating guidelines regarding the safe and sustainable utilization of plant-synthesized AgNPs across a broad spectrum of applications, as emphasized by Jamil et al.74. Based on the percentage cell viability of phyto-produced NPs, Figs. 16(a) and (b) depict the effect of UA-AgNPs on Vero cells. In our investigation, UA-AgNPs exhibited an IC50 of 5.59 µg/mL in Vero cells, indicating cytotoxicity at higher concentrations. The selectivity index (SI) for UA-AgNPs has been calculated using the ratio of Vero cell IC50 to HeLa cell IC50, yielding an SI value of 5.02. This substantial difference indicates that UA-AgNPs can target cancer cells at concentrations well below those affecting normal cells, which is a key advantage for potential biomedical applications. According to Zhong et al.75, AgNPs exhibited no negative effects on the Vero cell line. This indicates that anticancer medications or substances with target specificity (targeted treatment) selectively kill tumor cells devoid of harming control cells. The biocompatibility of the AgNPs was determined by size, shape, and surface functionalization, while specific conditions may pose risks. The UA-AgNPs show minimal cytotoxicity to Vero cells; they exhibit anticancer activity against HeLa cells. This highlights the need to assess potential environmental risks, as released NPs could harm aquatic life or soil microorganisms. To reduce environmental risks, biodegradable coatings, controlled release systems, and eco-toxicological studies can help minimize NPs persistence and toxicity. Optimizing green synthesis for lower cytotoxicity and integrating wastewater filtration systems can further ensure the safe and sustainable use of NPs76. Even though several studies show that biocompatible AgNPs can be used in biological applications such as imaging and medication administration, the controlled release in specific biological situations improves therapeutic effectiveness while reducing negative effects on healthy tissues77.

(a) Cytotoxicity evaluation in Vero cells; (b) Percentage of cell viability. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation of three replicates. Distinct superscript letters (a, ab, b, etc.) within the same column denote statistically significant differences among the treatment groups (p < 0.05) according to Tukey’s multiple range test. Groups bearing the same letter do not differ significantly from one another.

Nitric oxide determination

To investigate the inhibitory impact of UA-AgNPs in treating inflammatory disease, we employed an in vitro model of LPS (Lipopolysaccharide)-induced RAW 264.7 macrophage cells. Cells were also chosen since they are commonly used as targeted single cells for assessing immunological reactivity. LPS is a component of gram-negative bacteria that causes macrophages to engage in inflammatory activity78. The green synthesized AgNPs were able to lower the production of NO levels in RAW 264.7 macrophage cells in a dose-dependent manner. Treatment with UA-AgNPs at a concentration of 1, 10, 20, and 50 µg/mL showed NO production of 18.15, 10.97, 3.55, and 2.62 µg/mL, respectively, which were significantly lower than LPS-treated cells (36.11 µg/mL) (Fig. 17). NO generated by macrophages (microglia in neural tissue) is known to assist in the inflammatory process by producing peroxynitrite, an effective oxidizing agent required for immunological defense against pathogens. Furthermore, the extremely reactive nitric oxide becomes more sensitive when it is coupled with oxygen, resulting in highly reactive molecules that can cause a range of repercussions, including cellular damage and neurotoxicity79. As a result, regulating excess NO generation by either scavenging NO or inhibiting inducible NO gene expression in macrophages is a promising treatment strategy for several inflammation-mediated illnesses80,81. The observed anti-inflammatory assay of UA-AgNPs in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages is likely mediated through multiple pathways. By down regulating inducible nitric oxide synthase expression and blocking NF-κB activation, UA-AgNPs reduce the transcription of pro-inflammatory mediators, leading to a marked decrease in nitric oxide (NO) production. In addition, their intrinsic antioxidant properties may scavenge ROS, further mitigating oxidative and nitrosative stress. This combined effect suggests that UA-AgNPs modulate inflammatory signaling at both transcriptional and oxidative levels82. Based on our present findings, UA-AgNPs manufactured using plants were appropriate for free radical scavenging activity in vitro and might be used as possible anti-inflammatory medicines.

Quantification of nitric oxide levels. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation of three replicates. Distinct superscript letters (a, ab, b, etc.) within the same column denote statistically significant differences among the treatment groups (p < 0.05) according to Tukey’s multiple range test. Groups bearing the same letter do not differ significantly from one another.

Docking analysis of UA-AgNPs

In this study, AgNO3 was employed as a simplified ligand model for docking, as intact UA-AgNPs cannot be directly processed in conventional docking algorithms due to their heterogeneous, multi-component structure. The AgNO3 model represents the reactive silver moiety that is likely to engage with protein targets, while acknowledging that in vivo, the full UA-AgNPs interact through both the metallic core and the ursolic acid capping layer, as well as potential adsorbed biomolecules. The results of molecular docking revealed that the AgNO3 ligand, on interaction with LasB, showed a free binding energy of −7.63 kcal/mol and formed a total of 6 hydrogen bonds. The N and O group of the ligands formed a bond with Ala A:113 at 2.92687 Å and 1.85567 Å, and the double oxygen bond of the ligand connected with Tyr A:155, His A:144, His A:140, and His A:223 at 2.97918 Å, 2.15662 Å, 2.10663 Å, and 2.00162 Å. For the HblL1 protein, the ligand exhibited a binding free energy of −6.28 kcal/mol, also with 2 hydrogen bonds; the oxygen atom of the ligand bonded with Asp B:347 at 1.93953Å, and the Ag group bonded with Asp B:346 at 1.82049 Å. On the other hand, VEGFR 2 protein interacted with a ligand and displayed binding free energy of −5.67 kcal/mol with 2 hydrogen bonds; the two-nitrogen atom bonded with Leu R:151 and the at 2.20236 Å and 1.8529 Å, respectively (Fig. 18; Table 2). Meanwhile, the molecular docking analysis revealed strong binding affinities of UA-AgNPs with BRCA1 (ΔG = −8.6 kcal/mol; Ki ≈ 0.49 µM), C-erbB2 (ΔG = −8.2 kcal/mol; Ki ≈ 0.89 µM), Hbl (ΔG = −7.9 kcal/mol; Ki ≈ 1.46 µM), and aglD (ΔG = −7.6 kcal/mol; Ki ≈ 2.39 µM). The low micromolar Ki values indicate strong binding potential, supporting the relevance of these targets to the biological activities observed. The binding energies obtained (−5.67 kcal/mol for VEGFR2) should therefore be interpreted as indicative of possible silver protein interactions rather than definitive predictors of biological potency. The observed in vitro cytotoxicity against HeLa cells (IC50 = 29.20 µg/mL) is likely mediated by multiple mechanisms, including oxidative stress induction, membrane disruption, and multivalent binding events at the cellular interface, which are not fully captured in docking simulations. In addition, binding to Hbl supports the antibacterial effects, potentially through inhibition of pore-forming toxins, while interaction with aglD may contribute to antibiofilm activity by disrupting exopolysaccharide biosynthesis. By combining these computational insights with our experimental cytotoxicity, antibacterial, and biofilm inhibition data, we propose that the biological effects of UA-AgNPs arise from synergistic interactions between surface-bound silver species and bioactive ursolic acid moieties, rather than from a single molecular binding event. Indeed, our docking research demonstrated higher binding free energy values across all selected receptors as well as significant electrostatic interaction, allowing the receptor and ligand to achieve faultless orientation with proximity, implying that green-synthesized UA-AgNPs may provide insight into drug discovery opportunities in the healthcare industry83. Similarly, Elumalai et al.84 reported that the possibility of potential binding affinity and interaction of biosynthesized AgNPs targeted the virulence protein (BRCA1 and C-erbB2) of breast cancer and pathogenic bacterial strains such as S. aureus, E. coli, E. faecalis, and P. aeruginosa (SpA, Ag43, esp, and aglD), respectively.

The Molecular Docking of AgNO3 NPs ligand showed the highest affinity with Breast cancer cells (MCF7) virulence proteins and proteins of different bacterial organisms. (a, d,g) 2D interaction of the ligand with LasB protein, 3D complex structure, and Ramachandran plot respectively (b, e,h) 2D interaction of the ligand with HblL1 protein, 3D complex structure and Ramachandran plot respectively (c, f,i) 2D interaction of the ligand with VEGFR 2 protein, 3D complex structure, and Ramachandran plot respectively.

Conclusion

The use of plant metabolites as potential biomechanical tools in synthesizing AgNPs is a burgeoning field of study in nanobiotechnology. Within this investigation, AgNPs were produced utilizing the ursolic acid metabolite extracted from the C. roseus plant as a reducing and stabilizing agent, presenting a novel and advantageous strategy for AgNPs synthesis in contrast to conventional chemical approaches. However, the thorough evaluation of the synthesized AgNPs and the appraisal of their antibacterial effectiveness hold significant importance due to the escalating concern of antibiotic resistance on a global scale. The observed in vitro activities, including antibacterial, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and preliminary anticancer effects, suggest that UA-AgNPs have promising biomedical potential. Nevertheless, without pharmacokinetic profiling and in vivo validation, these findings should be interpreted as early-stage indicators rather than confirmed therapeutic outcomes. Future work will focus on broader cell line testing, targeted drug delivery, dose response pharmacokinetics, and animal model studies to substantiate their clinical relevance. Additionally, the UA-AgNPs exhibited notable antioxidant capabilities for treating ailments related with oxidative stress. The innovation of this method was discovered to be simple and non-hazardous, with the resulting AgNPs showing promise for commercial applications, thus representing a significant stride in the realms of human health and medicinal practices. The synthesis of AgNPs produces stable, uniformly dispersed, and negatively charged spherical NPs possessing a face-centered cubic crystal lattice structure. Nonetheless, further research is imperative to unravel the mechanisms of plant-mediated AgNPs relevant to biomedical uses, a domain that remains obscure. Such investigations have the potential to elucidate the workings and efficiency of AgNPs to combat NP resistance.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

-

Kannappan, S., Gowrishankar, R., Srinivasan, S. K., Pandian, A. V. & Ravi Antibiofilm activity of vetiveria zizanioides root extract against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Microb. Pathog. 110, 313–324 (2017).

-

Zeng, G. et al. Identification of anti-nociceptive constituents from the pollen of typha angustifolia L. using effect-directed fractionation. Nat. Prod. Res. 34 (7), 1041–1045 (2020).

-

Nagaraja, S. K., Chakraborty, B., Bhat, M. P. & Nayaka, S. Biofabrication of nano-silver composites from Indian catmint-Anisomeles ovata flower buds extract and evaluation of their potential in-vitro biological applications. Pharmacol. Research-Natural Prod. 7, 100246 (2025).

-

Manimegalai, T., Raguvaran, K., Kalpana, M. & Maheswaran, R. Facile synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Vernonia anthelmintica (L.) Willd. And their toxicity against spodoptera Litura (Fab.), Helicoverpa armigera (Hüb.), Aedes aegypti Linn. And culex quinquefasciatus say. J. Cluster Sci. 33 (5), 2287–2303 (2022).

-

Raguvaran, K., Kalpana, M., Manimegalai, T. & Maheswaran, R. Insecticidal, not-target organism activity of synthesized silver nanoparticles using actinokineospora fastidiosa. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 38, 102197 (2021).

-

Sangeeta, M. K. et al. Mahalingam. In-vitro evaluation of talaromyces Islandicus mediated zinc oxide nanoparticles for antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, bio-pesticidal and seed growth promoting activities. Waste Biomass Valoriz. 15 (3), 1901–1915 (2024).

-

Rudrappa, M. et al. Plumeria alba-mediated green synthesis of silver nanoparticles exhibits antimicrobial effect and anti-oncogenic activity against glioblastoma U118 MG cancer cell line. Nanomaterials 12 (3), 493 (2022).

-

Shashiraj, K. N. et al. Exploring the antimicrobial, anticancer, and apoptosis inducing ability of biofabricated silver nanoparticles using lagerstroemia speciosa flower buds against the human osteosarcoma (MG-63) cell line via flow cytometry. Bioengineering 10 (7), 821 (2023).

-

Wu, B., Wang, Z., Xie, H., Xie, P. & Ma Dimethyl Fumarate Augments Anticancer Activity of Ångstrom Silver Particles in Myeloma Cells through NRF2 Activation. Advanced Therapeutics, 8(1), 2400363.S. (2025).

-

Sulthana, A. S. et al. Design, preparation, and in vitro characterizations of chitosan-loaded nanostructured lipid carriers: a promising drug delivery system. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery, 14, 26459–26476 (2024).

-

Kamatchi, P. A. C. et al. Bioefficacy of ursolic acid and its derivatives isolated from catharanthus roseus (L) G. Don leaf against Aedes aegypti, culex quinquefasciatus, and Anopheles stephensi larvae. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30 (26), 69321–69329 (2023).

-

Chirumamilla, P., Dharavath, S. B., Taduri & S. and Eco-friendly green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from leaf extract of solanum khasianum: optical properties and biological applications. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 195 (1), 353–368 (2023).

-

ICMR (Indian Council of Medical Research). National ethical guidelines for biomedical and health research involving human participants. 2017 New Delhi Indian Council of Medical Research. Availablefrom: https://www.icmr.nic.in/sites/default/files/guidelines/ICMR_Ethical_Guidelines_2017.pdf

-

Nagasundaram, N. et al. Synthesis, characterization and biological evaluation of novel Azo fused 2, 3-dihydro-1H-perimidine derivatives: in vitro antibacterial, antibiofilm, anti-quorum sensing, DFT, in Silico ADME and molecular Docking studies. J. Mol. Struct. 1248, 131437 (2022).

-

Clinical, L. S. & Institute Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing, Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute Wayne, PA, pp. 106–112. (2017).

-

Mohamad Hanafiah, R. et al. Green synthesis, characterisation and antibacterial activities of strobilanthes crispus-mediated silver nanoparticles (SC-AGNPS) against selected bacteria. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 51 (1), 549–559 (2023).

-

Muniasamy, S. et al. Green Synthesis of Copper Nanoparticles Using Panchagavya: Nanomaterials for Antibacterial, Anticancer, and Environmental Applications. Luminescence 40 (2), e70117 (2025).

-

Abinaya, M. & Gayathri, M. Inhibition of biofilm formation, quorum sensing activity and molecular Docking study of isolated 3, 5, 7-Trihydroxyflavone from Alstonia scholaris leaf against P. aeruginosa. Bioorg. Chem. 87, 291–301 (2019).

-

Kannappan, A. et al. Antibacterial activity of 2-hydroxy-4-methoxybenzaldehyde and its possible mechanism against Staphylococcus aureus. J. Appl. Microbiol. 134 (7), lxad144 (2023).

-

Raguvaran, K., Kalpana, M., Manimegalai, T. & Maheswaran, R. Larvicidal, antibacterial, antibiofilm, and anti-quorum sensing activities of silver nanoparticles biosynthesized from streptomyces sclerotialus culture filtrate. Mater. Lett. 316, 132000 (2022).

-

Khuda, F. et al. Assessment of antioxidant and cytotoxic potential of silver nanoparticles synthesized from root extract of reynoutria Japonica Houtt. Arab. J. Chem. 15 (12), 104327 (2022).

-

Landeros-Páramo, L., Saavedra-Molina, A., Gómez-Hurtado, M. A. & Rsosas, G. The effect of AgNPS bio-functionalization on the cytotoxicity of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. 3 Biotech. 12 (9), 196 (2022).

-

Feng, C. et al. Precisely tailoring molecular structure of doxorubicin prodrugs to enable stable Nanoassembly, rapid Activation, and potent antitumor effect. Pharmaceutics 16 (12), 1582 (2024).

-

Delalat, R., Sadat Shandiz, S. A. & Pakpour, B. Antineoplastic effectiveness of silver nanoparticles synthesized from onopordum acanthium L. extract (AgNPs-OAL) toward MDA-MB231 breast cancer cells. Mol. Biol. Rep. 49 (2), 1113–1120 (2022).

-

Wypij, M. et al. Green synthesized silver nanoparticles: antibacterial and anticancer activities, biocompatibility, and analyses of surface-attached proteins. Front. Microbiol. 12, 632505 (2021).

-

Farooqi, M. A. et al. Eco-friendly synthesis of bioactive silver nanoparticles from black roasted gram (Cicer arietinum) for biomedical applications. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 22922 (2024).

-

SPSS, C. & Ibm IBM SPSS statistics for Windows, Armonk (NY): IBM Corp (2012).

-

Kuppusamy, P., Yusoff, M. M., Maniam, G. P. & Govindan, N. Biosynthesis of metallic nanoparticles using plant derivatives and their new avenues in Pharmacological applications–An updated report. Saudi Pharm. J. 24 (4), 473–484 (2016).

-

Ying, S. et al. Green synthesis of nanoparticles: current developments and limitations. Environ. Technol. Innov. 26, 102336 (2022).

-

Zuhrotun, A., Oktaviani, D. J. & Hasanah, A. N. Biosynthesis of gold and silver nanoparticles using phytochemical compounds. Molecules 28 (7), 3240 (2023).

-

Tripathy, A., Raichur, A. M., Chandrasekaran, N., Prathna, T. & Mukherjee, A. Process variables in biomimetic synthesis of silver nanoparticles by aqueous extract of Azadirachta indica (Neem) leaves. J. Nanopart. Res. 12, 237–246 (2010).

-

Guzman, M., Dille, J. & Godet, S. Synthesis and antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 8 (1), 37–45 (2012).

-

Rahimzadeh, C. Y., Barzinjy, A. A., Mohammed, A. S. & Hamad, S. M. Green synthesis of SiO2 nanoparticles from Rhus coriaria L. extract: comparison with chemically synthesized SiO2 nanoparticles. PLoS One. 17 (8), e0268184 (2022).

-

Prathna, T., Chandrasekaran, N., Raichur, A. M. & Mukherjee, A. Biomimetic synthesis of silver nanoparticles by citrus Limon (lemon) aqueous extract and theoretical prediction of particle size. Colloids Surf., B. 82 (1), 152–159 (2011).

-

Alharbi, N. S., Alsubhi, N. S. & Felimban, A. I. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using medicinal plants: characterization and application. J. Radiation Res. Appl. Sci. 15 (3), 109–124 (2022).

-

Shaik, M. R. et al. Plant-extract-assisted green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Origanum vulgare L. extract and their microbicidal activities. Sustainability 10 (4), 913 (2018).

-

Bawazeer, S. et al. Punica granatum Peel extracts mediated the green synthesis of gold nanoparticles and their detailed in vivo biological activities. Green. Process. Synthesis. 10 (1), 882–892 (2021).

-

Li, S. et al. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using capsicum annuum L. extract. Green Chem. 9 (8), 852–858 (2007).

-

Altemimi, A., Lakhssassi, N., Baharlouei, A., Watson, A. D. & Lightfoot, D. A. Phytochemicals: Extraction, isolation, and identification of bioactive compounds from plant extracts. Plants 6 (4), 42 (2017).

-

Baran, A. et al. Green-synthesized nanoparticles for biomedical sensor technology. In Nanosensors Healthc. Diagnostics, 13, 355–380 (2025).

-

Priya, R. S., Geetha, D. & Ramesh, P. Antioxidant activity of chemically synthesized AgNPs and biosynthesized Pongamia pinnata leaf extract mediated AgNPs–A comparative study. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 134, 308–318 (2016).

-

Batterjee, M. G. H. Extraction of Phytochemicals and their Use in the Preparation of Metallic Nanoparticles and Metal Oxides for Enhanced Catalytic and Antimicrobial Applications (King Abdulaziz University, 2023).

-

Duman, H. et al. Silver nanoparticles: A comprehensive review of synthesis methods and chemical and physical properties. Nanomaterials 14 (18), 1527 (2024).

-

Singh, C. et al. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles by root extract of Premna integrifolia L. and evaluation of its cytotoxic and antibacterial activity. Mater. Chem. Phys. 297, 127413 (2023).

-

Bhattacharjee, S. DLS and zeta potential–what they are and what they are not? J. Controlled Release. 235, 337–351 (2016).

-

Shrestha, S., Wang, B. & Dutta, P. Nanoparticle processing: Understanding and controlling aggregation. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 279, 102162 (2020).

-

Chandraker, S. K., Ghosh, M. K., Lal, M. & Shukla, R. A review on plant-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles, their characterization and applications. Nano Express. 2 (2), 022008 (2021).

-

Suriyakalaa, U. et al. Hepatocurative activity of biosynthesized silver nanoparticles fabricated using andrographis paniculata. Colloids Surf., B. 102, 189–194 (2013).

-

Rajput, S., Kumar, D. & Agrawal, V. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Indian Belladonna extract and their potential antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anticancer and larvicidal activities. Plant Cell Rep. 39 (7), 921–939 (2020).

-

Salleh, A. et al. The potential of silver nanoparticles for antiviral and antibacterial applications: A mechanism of action. Nanomaterials 10 (8), 1566 (2020).

-

Son, J. & Lee, S. Y. Therapeutic potential of ursonic acid: comparison with ursolic acid. Biomolecules 10 (11), 1505 (2020).

-

Lara, H. H., Ayala-Núñez, N. V. & Ixtepan Turrent, L. C. Rodríguez Padilla, bactericidal effect of silver nanoparticles against multidrug-resistant bacteria. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 26, 615–621 (2010).

-

Zhang, Y., Liu, X., Wang, Y., Jiang, P. & Quek, S. Antibacterial activity and mechanism of cinnamon essential oil against Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus. Food Control. 59, 282–289 (2016).

-

Barabadi, H. et al. Bioinspired green-synthesized silver nanoparticles: in vitro physicochemical, antibacterial, biofilm inhibitory, genotoxicity, antidiabetic, antioxidant, and anticoagulant performance. Mater. Adv. 4 (14), 3037–3054 (2023).

-

Rajivgandhi, G. et al. Biosynthesized silver nanoparticles for Inhibition of antibacterial resistance and biofilm formation of methicillin-resistant coagulase negative Staphylococci. Bioorg. Chem. 89, 103008 (2019).

-

Talank, N. et al. Bioengineering of green-synthesized silver nanoparticles: in vitro physicochemical, antibacterial, biofilm inhibitory, anticoagulant, and antioxidant performance. Talanta 243, 123374 (2022).

-

Ansari, M. A. et al. Counteraction of biofilm formation and antimicrobial potential of terminalia Catappa functionalized silver nanoparticles against Candida albicans and multidrug-resistant Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria. Antibiotics 10 (6), 725 (2021).

-

Seder, N., Rayyan, W. A., Al-Fawares, M. H. O. & Bakar, A. Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence factors and antivirulence mechanisms to combat drug resistance; A systematic review. Mortality 10 (11), 1–23 (2023).

-

Pham, D. T. N. et al. Biofilm inhibition, modulation of virulence and motility properties by FeOOH nanoparticle in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Brazilian J. Microbiol. 50, 791–805 (2019).

-

You, C. et al. The progress of silver nanoparticles in the antibacterial mechanism, clinical application and cytotoxicity. Mol. Biol. Rep. 39, 9193–9201 (2012).

-

Gulcin, I. Antioxidants and antioxidant methods: an updated overview. Arch. Toxicol. 94 (3), 651–715 (2020).

-

De Menezes, B. B., Frescura, L. M., Duarte, R. & Villetti, M. A. Da Rosa. A critical examination of the DPPH method: mistakes and inconsistencies in stoichiometry and IC50 determination by UV–Vis spectroscopy. Anal. Chim. Acta. 1157, 338398 (2021).

-

Gonzales, M., Villena, G. K. & Kitazono, A. A. Evaluation of the antioxidant activities of aqueous extracts from seven wild plants from the Andes using an in vivo yeast assay. Results Chem. 3, 100098 (2021).

-

Zhang, L. et al. Ten-gram-scale mechanochemical synthesis of ternary lanthanum coordination polymers for antibacterial and antitumor activities. Front. Chem. 10, 898324 (2022).

-

Keshari, A. K., Srivastava, R., Singh, P., Yadav, V. B. & Nath, G. Antioxidant and antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles synthesized by cestrum nocturnum. J. Ayurveda Integr. Med. 11 (1), 37–44 (2020).

-

Dupont, S. et al. Simon-Plas, antioxidant properties of ergosterol and its role in yeast resistance to oxidation. Antioxidants 10 (7), 1024 (2021).

-

Liu, C. G. et al. Intracellular redox perturbation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae improved furfural tolerance and enhanced cellulosic bioethanol production. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 8, 615 (2020).

-

Gomathi, A., Rajarathinam, S. X., Sadiq, A. M. & Rajeshkumar, S. Anticancer activity of silver nanoparticles synthesized using aqueous fruit shell extract of tamarindus indica on MCF-7 human breast cancer cell line. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 55, 101376 (2020).

-

Smith, S. M., Ribble, D., Goldstein, N. B., Norris, D. A. & Shellman, Y. G. A simple technique for quantifying apoptosis in 96-well plates. Methods Cell. Biol. 112, 361–368 (2012).

-

Song, Y., Huang, Y., Zhou, F., Ding, J. & Zhou, W. Macrophage-targeted nanomedicine for chronic diseases immunotherapy. Chin. Chem. Lett. 33 (2), 597–612 (2022).

-

Wu, A. et al. COPZ1 regulates ferroptosis through NCOA4-mediated ferritinophagy in lung adenocarcinoma. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta (BBA)-General Subj. 1868 (11), 130706 (2024).

-

Gupta, R. & Xie, H. Nanoparticles in daily life: applications, toxicity and regulations. J. Environ. Pathol. Toxicol. Oncol. 37 (3), 209–230 (2018).

-

Deivayanai, V. C. et al. Advances in nanoparticle-mediated cancer therapeutics: current research and future perspectives. Cancer Pathogenesis Therapy. 3 (4), 293 (2024).

-

Jamil, K. et al. Biogenic synthesis of silver nanoparticles using catharanthus roseus and its cytotoxicity effect on Vero cell lines. Molecules 27 (19), 6191 (2022).

-

Zhong, L. et al. Small molecules in targeted cancer therapy: advances, challenges, and future perspectives. Signal. Transduct. Target. Therapy. 6 (1), 1–48 (2021).

-

Keller, A. A., McFerran, S., Lazareva, A. & Suh, S. Global life cycle releases of engineered nanomaterials. J. Nanopart. Res. 15, 1–17 (2013).

-

Huda Abd Kadir, N., Ali Khan, A., Kumaresan, T., Khan, A. U. & Alam, M. The impact of pumpkin seed-derived silver nanoparticles on corrosion and cytotoxicity: a molecular Docking study of the simulated AgNPs. Green Chem. Lett. Rev. 17 (1), 2319246 (2024).

-

Ahmad, R., Hassan, N., Dhiman, A. & Ali Assessment of anti-inflammatory activity of 3-acetylmyricadiol in LPSStimulated Raw 264.7 macrophages. Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screen. 25 (1), 204–210 (2022).

-

Hancock, J. T. & Neill, S. J. Nitric oxide: its generation and interactions with other reactive signaling compounds. Plants 8 (2), 41 (2019).

-

Wang, K. et al. Inhibition of inflammation by berberine: molecular mechanism and network Pharmacology analysis. Phytomedicine 128, 155258 (2024).

-

Solaiman, M. A., Ali, M. A., Abdel-Moein, N. M. & Mahmoud, E. A. Synthesis of Ag-NPs developed by green-chemically method and evaluation of antioxidant activities and anti-inflammatory of synthesized nanoparticles against LPS-induced NO in RAW 264.7 macrophages. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 29, 101832 (2020).