Introduction

The global impact of bacterial infections is profound, with over fifty thousand deaths reported daily1. In response, silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) have emerged as highly effective agents against pathogens, viruses, and micro-organisms2 due to their high specific surface area and exceptional biocidal activity3. Consequently, AgNPs have found extensive applications in medicine4, catalysis 5, biotechnology 6 and functional textile finishing7,8.

Various methods for synthesizing AgNPs have been employed, such as: electrochemical9,10, photochemical11,12,13,14, microwave16, thermal17,18, and radiation-based methods19,20 have been employed for AgNPs synthesis, there is an urgent need for “green” synthesis routes. Conventional methods often rely on toxic reducing agents and chemical dispersants that pose environmental risks21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33.

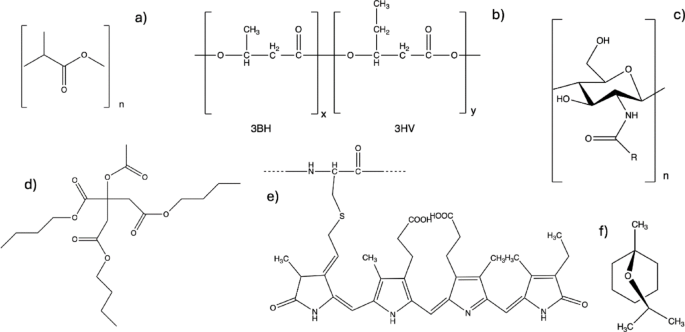

Over the previous decade, polysaccharides have been utilized as “green alternative34 to conventional agents have been used such as alginate35, starch33 chitin36, chitosan30 have been utilized as eco-friendly alternatives11,12,14,37,38,39,40,41. Among these, carboxymethyl chitosan (CMC) stands out as a promising candidate due to its water solubility, biodegradability, and non-toxicity42,43. Its inherent amine and carboxylic groups allow it to function simultaneously as a reducing and capping agent, facilitating the transition from Ag+ to Ag0 while ensuring nanoparticle stability44,45.

Photochemical synthesis has gained significant interest as a green physical method because it offers precise control over nanoparticle size and shape with minimal chemical usage46,47,48. In this study, we propose a novel, all-green photo-induced system for synthesizing CMC-Ag nanocomposites. This approach utilizes a water-soluble 4-(trimethyl ammonium methyl) benzophenone chloride as a safe photo-initiator49. This compound, often used in sun-protection cosmetics, serves as an eco-friendly radical generator under UV irradiation to facilitate silver reduction.

In this work, 4- (trimethyl ammonium methyl) benzophenone chloride was used as a photo-initiator. It can, therefore, be described as a safe, and eco-friendly and a green compound. Thus, the current work is built on the basis of using all green chemicals namely, CMC (reducing and capping agent), 4-(trimethyl ammonium methyl) benzophenone chloride (photo initiator), and methods (UV-photo initiator reducing system) for synthesis of CMC-Ag nanocomposite.

The primary objectives of this research are: (1) to develop a new green initiation system using a UV/photo-initiator (125W Hg lamp) for CMC-Ag-nanocomposite preparation; (2) to optimize synthesis parameters using only green components (CMC as polymer, water as solvent, and safe benzophenone PI); (3) to characterize the resulting nanocomposite using FTIR, TEM, XRD, and SEM; and (4) to evaluate the antibacterial efficacy and durability of the finished cotton fabrics against human pathogenic bacteria for potential use in medical textiles and wound dressings50. To our knowledge, this is the first report on AgNPs preparation using CMC mediated by this specific benzophenone photo-initiator under UV irradiation.

Experimental

Materials and chemicals

Scoured and bleached plain weave cotton fabric (100%, 158 g/m2) was purchased from Misr Helwan Spinning and Weaving Company (Egypt) and cut into 10 cm × 10 cm samples.

Chitosan (low molecular weight, 75–80% deacetylation) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH. Other reagents, including silver nitrate (AgNO3, 99.8%), sodium hydroxide (NaOH, 98%), isopropanol, monochloroacetic acid, ethanol, and 4-(trimethyl ammonium methyl) benzophenone chloride (PI), were of analytical grade and used without further purification.

Equipment

The irradiation reaction vessel consisted of a water-cooled 125W medium-pressure Hg lamp assembly. The overall dose of UV irradiation was controlled via controlling the exposure period, or reaction time. A thermostatic water bath was used to regulate the reaction temperature.

Characterization

Degree of substitution (DS) of carboxymethyl chitosan (CMC) was determined via potentiometric titration following a reported method50. Briefly, CMC was dissolved in distilled water, and the pH was adjusted to < 2 using hydrochloric acid. The solution was then titrated against 0.1 M NaOH while continuously monitoring the pH. The endpoint was identified using the second-order derivative method, and the DS was calculated as follows:

$$DS=(161*text{A})/(text{m}(text{CMC})-58text{A})$$

A = V (sodium hydroxide) × C (sodium hydroxide).

Where VNaOH and CNaOH represent the volume and molarity of the sodium hydroxide solution, respectively. mCMC denotes the mass of the CMC sample (g). The values 161 and 58 correspond to the molecular weights of the glucosamine unit and the carboxymethyl group, respectively. All measurements were performed in triplicate.

UV-2401 UV–vis Spectrophotometer, Shimadzu, Japan, was used to measure the absorbance of the colloidal solution of CMC-Ag-nanocomposite. The UV–vis spectrum of the nanocomposite was captured at wavelengths between 300 and 485 nm.

A JEOL JEM 1200 transmission electron microscope (TEM) was used to examine the shape and particle size of AgNPs.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) model Joel 840A was used to examine the surface morphology of the cotton fabric loaded with CMC-Ag-nanocomposite.

Perkin-Elmer spectrum 1000 spectrophotometer was used to obtain the Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra of the samples. Spectra were recorded using the KBr pellet method. The wave numbers used to scan the FTIR spectra ranged from 400 to 4000 (cm-1).

By monitoring the diffraction angle from 0° to 70° (2θ) at 40 keV, X-Ray diffraction experiments were carried out utilizing Philips PW3040 X-Ray diffractometer. The analysis was performed using the Powder X-ray Diffraction (PXRD) method.

According to ASTM procedure D-2296-66T, the tensile strength and elongation at break tests of cotton fabric were conducted on both unloaded and loaded cotton fabrics with CMC-Ag-nanocomposite.

The AATCC Test (147–2004) standard test method was used to assess the antibacterial activity of treated cotton fabrics51. The results of an antibacterial test against Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus were expressed as a zone of growth inhibition (mm).

Preparation of carboxymethyl chitosan

A reported method52 was used to prepare CMC with minor changes. Briefly, chitosan (50g) and sodium hydroxide (24.85g) were added into a sealable jar containing a mixture of water and isopropanol (300 water: 700 isopropanol) to swell chitosan for 2h at 60◦C. Then (29.35g) monochloroacetic acid dissolved in isopropanol were added dropwise through 30 min. After continued stirring for an additional 4h at 60 °C, 200ml of 70% ethyl alcohol were added. The solid was filtered out, rinsed with 80% ethyl alcohol to desalt and dewater the CMC, and then dried at 60◦C. The product was a Na-salt of CMC (CMC-Na).

To obtain CMC hydrogen form (CMC-H), two grams of the CMC-Na were suspended in 100ml of 80% ethyl alcohol, and 10 ml of 37% hydrochloric acid were added and stirred for 30 min. The solid was filtered out, rinsed many times with 80% ethyl alcohol till neutral, and finally dried at 60°C. The synthesis reaction is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Synthesis of CMC-Ag-nanocomposite

In a total volume of 140 cm3, a specific weight of CMC was placed in the irradiation reaction vessel and dissolved under magnetic stirring. After full dissolution, a certain weight of PI solution was introduced, and the reaction temperature was raised to the desired temperature. After that, a specific weight of silver nitrate solution was then added dropwise, the pH was finally adjusted to 7. The UV lamp was immersed in the solution, positioned just above the bottom of the tube to facilitate magnetic stirring and ensure uniform UV irradiation of the entire mixture, then it was switched on, the cooling system was employed, and the irradiation reaction was allowed to continue for certain length of time under continuous stirring. The color of reaction solution started to develop from colorless to bright yellow just after adding silver nitrate. With time, the bright yellow color was developed to dark yellow, brown, and finally dark brown by end of reaction. This observation suggested the formation of AgNPs. After the completion of the reaction, the UV-lamp was switched off and the CMC-Ag-nanocomposite was collected and kept in a sealable glass bottle for further use.

Finishing cotton fabrics with CMC-Ag-nanocomposite

The cotton fabrics were padded with the nanocomposite solution using a laboratory padding mangle (1 dip, 1 nip) at room temperature for 1h, to achieve a wet pick-up of 100%, then they dried at 60°C for 20 min., thoroughly rinsed with distilled water, and air dried.

Results and discussion

Degree of substitution (DS) of carboxymethyl chitosan (CMC)

CMC samples were prepared with different degrees of substitution (DS) as shown in Table 1. The carboxyl content and the DS were measured and calculated according to the method mention in the experimental section. Table 2 showed COOH percentages of each level.

Synthetic mechanism of CMC-Ag-nanocomposite

The CMC-Ag-nanocomposite’s proposed synthesis methods are shown in Fig. 2. The literature53 states that the use of CMC caused the PI to form reactive radical species when exposed to UV light (1). By combining two PI (2) radicals to form the pinacol derivative (I), inactive species can be created (Fig. 2). The generation of the CMC• radical initiates a photooxidation process (1). The aldehydic end groups that were recently produced as a result of the photooxidation activity, as well as the hydroxyl and carboxyl groups that were previously present in the CMC molecules, can all function as Ag+ to Ag0 reducing groups. Additionally, as seen in Eq. (3), the radical of the PI created by Eq. (1) has the ability to further transform the silver ions into AgNPs.

Effect of degree of substitution (DS) of carboxymethyl chitosan (CMC) on synthesis of AgNPs

Different amounts of carboxymethyl groups in CMC were used with (DS of 3,5 and 7) moles. Figure 3 demonstrated that (i) all tested samples displayed a plasmon peak at wavelength 406 nm, which was typical for silver nanoparticle colloidal solution, regardless of the DS of CMC utilised, and (ii) at DS of 3 mol, the absorption was larger and subsequently decreased. The considerable decrease in absorption intensity, which suggests decreased stability and greater aggregation of silver nanoparticles, may be the cause of this decrease54.

Reaction conditions: AgNO3, (0.14)g; PI, (0.07)g; CMC,( 0.7)g; Time (60) min; Temp. (40)oC; Water (140)ml; DS,(3,5,7); pH,7.

Effect of silver nitrate concentrations on synthesis of CMC-Ag-nanocomposite

It is clear from Fig. 4 that at AgNO3 concentrations of (0.04,0.07,0.14, and 0.28) g, there are four intense bell-shaped bands. The Figure additionally showed that by raising the quantity of AgNO3 from 0.04 to 0.14g, the absorbance of the colloidal solution increased before decreasing. This might be explained by the fact that when the concentration of AgNO3 was between 0.04 and 0.14g, it boosted the synthesis of the CMC• radical and PI• as in Eq. (1) in just enough of a quantity to convert Ag+ to Ag0. For the conversion of all Ag+ to Ag0 when AgNO3 concentration was increased to more than 0.14g, additional radicals and reducing groups are needed. This can be achieved by simultaneously raising the concentrations of PI and AgNO3. When a larger concentration of AgNO3 was utilised, it can also be attributed to agglomeration of the AgNO3 rather than the creation of capped silver nanoparticles in a colloidal solution55.

Reaction conditions: AgNO3, (0.04, 0.07, 0.14, 0.28)g; PI, (0.07)g; CM- chitosan, (1.4)g; Time (60) min.; Temp. (40)oC; Water (140)ml; DS,3; pH,7.

Effect of CMC concentrations on synthesis of CMC-Ag-nanocomposite

The UV–vis absorption spectrum of the CMC-Ag-nanocomposite solution, which was generated using different concentrations of CMC from (0.19–1.4) g, were shown in Fig. 5. At CMC concentrations of (0.198, 0.35, and 0.7) g, it was discovered that there are three intense bell-shaped bands, which confirmed the synthesis of CMC-Ag-nanocomposite. Additionally, it is clear that a broad band without bell-shaped characteristics exists at 1.4 g of concentration. The figure additionally showed that the absorbance of the solution increased when the concentration of CMC was raised from (0.19–0.7) g and reduced when the concentration was raised. This could be due to the fact that an increase in CM concentration could reduce the mobility of PI and AgNO3 and prevent the conversion of Ag+ to Ag056.

Reaction conditions: AgNO3, ( 0.14)g; PI,( 0.07)g; CMC, (0.198, 0.35, 0.7, 1.4) g; Time (60 ) min; Temp. (40)oC; Water (140)ml; DS,3; pH,7.

Effect of PI concentrations on synthesis of CMC-Ag-nanocomposite

The findings from Fig. 6 show that the absorbance of the solution dramatically increases when PI concentration increases from 0 to 0.07g which corresponds to a weight percentage range of 0 to 0.05 wt% (based on a total reaction volume of 140 ml). The absorption was reduced as the PI concentration continued increasing. This can be attributed to creation of the pinacol derivative (I) (reaction 2), which resulted in deactivation of photosynthesis of CMC-Ag-nanocomposite56.

Reaction conditions: AgNO3, (0.14)g; PI, (0, 0.035, 0.07, 0.14)g; CMC, (0.7)g; Time (60) min; Temp. (40)oC; Water (140)ml; DS,3; pH,7.

Effect of reaction time on synthesis of CMC-Ag-nanocomposite

The reaction time is equivalent to the irradiation time. Figure 7 displayed the effect of irradiation period ranging from 0 to 120 min on UV absorbance. Figure 7 shows that increasing the irradiation period up to 90 min. increased the UV absorption values. After 90 min. of exposure, the absorbance dropped. This could be owing to the increased concentration of PI radicals produced, which tends to homopolymerize PI to pinacol derivative (reaction 1). This failed to initiate the polymerization reaction therefore did not produce the CMC-Ag-nanocomposite57.

Reaction conditions: AgNO3, (0.14)g; PI,( 0.07)g; CMC, (0.7)g; Time (0,30,60,90,120) min; Temp. (40)oC; Water (140)ml; DS,(3); pH,(7).

Effect of reaction temperature on synthesis of CMC-Ag-nanocomposite

Different temperatures were utilised in the synthesis of CMC-Ag-nanocomposite to examine the effect of temperature on synthesis. Temperatures ranged from 30 °C to 70 °C. Figure 8 shows an increase in absorbance values from 30 °C to 70 °C, as well as a blue shift (hypsochromic shift) caused by particle size decrease from large to small. It was discovered that raising the temperature to 70°C increases the rate of silver ion reduction58.

Reaction conditions: AgNO3, (0.14)g; PI, ( 0.07)g; CMC, (0.7)g; Time (90) min; Temp. ( 30,40,50,60,70)°C; water (140)ml; DS,(3); pH,(7).

Characterization of CMC-Ag-nanocomposite

FT-IR analysis

The FT-IR spectra of CMC and CMC-Ag-nanocomposite (prepared under the previously identified optimum conditions: DS: 3, AgNO3: 0.14g, CMC: 0.7g, PI: 0.07g, irradiation time: 90 min, and temperature: 70°C at pH 7) have been analyzed in order to confirm the creation of the CMC-Ag-nanocomposite, as shown in Fig. 9. The peak at 3427cm-1 is the characteristic absorption of O–H stretching combined with N–H stretching, but in the CMC-Ag-nanocompositespectrum, the peak becomes narrower, indicating that there were less O–H or N–H in the CMC-Ag-nanocomposite spectra, or perhaps the N–H vibration was affected by the silver attachment59. Furthermore, the two bands at around 1619 and 1417 cm-1 in the CMC spectra are attributed to the asymmetric and symmetric peaks of -COOH groups, respectively. In the spectra of the CMC-Ag-nanocomposite, both bands weaken; additionally, a new weak peak at 1327 cm-1 belongs to the vibration of -CH3. These findings imply that during the creation of CMC-Ag-nanocomposite, certain carboxymethyl groups were oxidized to -CH3 groups.60.

Morphology analysis (TEM)

Examining the TEM image in Fig. 10 revealed that the CMC matrix contained spherical AgNPs of uniform size and small particle size. For CMC with DS 3,5 and 7, the AgNPs size distribution was centred in the range of 2–20, 2–10, and 2–12 nm, respectively. Additionally, CMC had mean diameters of 9, 4.5, and 3 nm for DS 3,5 and 7, respectively.

(a)Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) image of CMC-Ag-nanocomposite and (b) histogram of CMC-Ag-nanocomposite.

XRD analysis

Figure 11 displays the XRD patterns of the CMC and CMC-Ag-nanocomposite. Two significant distinctive crystalline peaks at 9.49° and 19.98° were seen in the XRD pattern of the CMC, which indicate crystallization. The crystalline peaks entirely disappeared from the composite of CMC and CMC-Ag-nanocomposite’ XRD pattern. Therefore, we concluded that in the CMC-Ag-nanocomposite, the crystal structure of the original polymer was damaged. This result can be attributed to the embedding of the silver particles in the CMC matrix, which interfered with intramolecular hydrogen bonding and the regularity of the polymer chains, leading to major changes in the crystalline structure of the polymer61.

Characterization of CMC-Ag-nanocomposite

SEM analysis

Figure 12 shows SEM images of cotton fabric and cotton fabric loaded with CMC-Ag-nanocomposite with degrees of substitution 3,5 and 7. The blank cotton fabric sample had a comparatively smooth surface in optical image (a), however numerous particles were discovered on the fabric surfaces loaded with CMC-Ag-nanocomposite in optical image (b). This modification was caused by the presence of CMC-Ag-nanocomposite on the cotton fabric.

Physical properties of loaded cotton fabric

Table 3 shows the tensile strength values (elongation and maximum force). Results suggest that there is a slight increase in elongation and maximum force of loaded cotton fabrics without producing major damage to the yarn structure, showing no significant difference between unloaded cotton fabrics and loaded cotton fabrics.

Antibacterial activity of loaded cotton fabric

The fabric’s antibacterial activity was measured using the AATCC Test (147–2004) method against Staphylococcus aureus as G + ve bacteria and Escherichia coli as G-ve bacteria and expressed as zone of growth inhibition (mm). There is no apparent zone of inhibition for unloaded cotton fabric and cotton fabric loaded with CMC-Ag-nanocomposite, as illustrated in Fig. 13 and Table 4. This is due to the lower NH2 content of CMC, which reduces antibacterial activity29. The presence of CMC-Ag-nanocomposite caused an obvious inhibition zone in cotton fabrics loaded with CMC-Ag-nanocomposite with varying degrees of substitution. Interestingly, the inhibition zone maintained its diameter or slightly increased after washing. This can be attributed to the ‘uncapping effect,’ where washing removes the excess unbound polymer film from the fabric surface, exposing a larger active surface area of the AgNPs62. Furthermore, the swelling of the CMC matrix in water facilitates the sustained release of Ag+ ions63.

Antibacterial activity of: (1) unloaded cotton, (2) cotton loaded with CMC, (3) cotton loaded with CMC-Ag-nanocomposite and (4) cotton loaded with CMC-Ag-nanocomposite after 20 washing cycles against S.aureus and E. coli test pathosgenic bacteria and that’s for the three degrees of substitution.

Conclusion

In this study, a highly efficient and entirely “green” photo-induced system was successfully developed for the synthesis of CMC-Ag nanocomposites. Unlike conventional chemical reduction methods, this approach offers a rapid synthesis that eliminates the need for toxic reducing agents.

The critical success of this methodology lies in the synergy between the cationic water-soluble benzophenone photo-initiator and the CMC matrix. The results demonstrate that the photo-initiator facilitates a controlled reduction process, yielding uniform spherical AgNPs with a small size distribution (10–25 nm), as confirmed by TEM. The chemical interaction between the carboxyl/amine groups of CMC and the silver surface not only stabilized the nanoparticles but also prevented agglomeration, which is often a challenge in green synthesis.

From a functional perspective, the application of these nanocomposites to cotton fabrics resulted in exceptional antibacterial performance against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. A key critical insight is the high durability of the finish; the treated fabrics retained significant bactericidal activity even after 20 washing cycles, suggesting a strong covalent or physical entrapment of the nanocomposite within the cellulose fibres. This research proves that the proposed photo-induced system is a viable, eco-friendly alternative for producing high-performance medical textiles and wound dressings, aligning with the global transition toward sustainable “Green Chemistry” in the textile industry.

Data availability

The datasets presented during or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

-

Bhardwaj, A. K. et al. Direct sunlight enabled photo-biochemical synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their Bactericidal Efficacy: Photon energy as key for size and distribution control. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 188, 42–49 (2018).

-

Rai, M., Yadav, A. & Gade, A. Silver nanoparticles as a new generation of antimicrobials. Biotechnol. Adv. 27(1), 76–83 (2009).

-

Xu, Q. et al. Antibacterial cotton fabric with enhanced durability prepared using silver nanoparticles and carboxymethyl chitosan. Carbohyd. Polym. 177, 187–193 (2017).

-

Salata, O. V. Applications of nanoparticles in biology and medicine. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2(1), 3 (2004).

-

Lewis, L. N. Chemical catalysis by colloids and clusters. Chem. Rev. 93(8), 2693–2730 (1993).

-

Niemeyer, C. M. Nanoparticles, proteins, and nucleic acids: Biotechnology meets materials science. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 40(22), 4128–4158 (2001).

-

Long, Y. et al. A method for the preparation of silver nanoparticles using commercially available carboxymethyl chitosan and sunlight. Mater. Lett. 112, 101–104 (2013).

-

Jafari, N. et al. Effect of silver particle size on color and antibacterial properties of silk and cotton fabrics. Fibers Polymers 17(6), 888–895 (2016).

-

Sargsyan, S.H., et al., Electrochemical synthesis of silver nanocomposites based on 1-vinyl-1,2,4-triazole and N-vinyl-caprolactam. Polymer Bull. (2024).

-

Daly, R., et al., Electrochemical synthesis of 2D-silver nanodendrites functionalized with cyclodextrin for SERS-based detection of herbicide MCPA. Nanotechnology 35(28) (2024).

-

El-Sheikh, M.A. Synthesis of conductive elastic film and conductive fabric based on crosslinked carboxymethyl starch-AgNPs composite. in NSTI: Advanced Materials – TechConnect Briefs 2015. USA, Mryland (2015).

-

El-Sheikh, M. A. A novel photosynthesis of carboxymethyl starch-stabilized silver nanoparticles. Sci. World J. 2014, 1–11 (2014).

-

El-Sheikh, M. A., El-Gabry, L. K. & Ibrahim, H. M. Photosynthesis of carboxymethyl starch-stabilized silver nanoparticles and utilization to impart antibacterial finishing for wool and acrylic fabrics. J. Polymers 2013, 1–9 (2013).

-

El-Sheikh, M. A. & Ibrahim, H. M. One step photopolymerization of N, N-methylene diacrylamide and photocuring of carboxymethyl starch-silver nanoparticles onto cotton fabrics for durable antibacterial finishing. Int. J. Carbohyd. Chem. 2014, 1–9 (2014).

-

Xiao, X.H., et al. Microwave-assisted biosynthesis of nano silver and its synergistic antifungal activity against Curvularia lunata. Front. Mater. 10 (2023).

-

Moorthy, K. et al. Evaluating antioxidant performance, biosafety, and antimicrobial efficacy of houttuynia cordata extract and microwave-assisted synthesis of biogenic silver nano-antibiotics. Antioxidants 13(1), 32 (2024).

-

Babaahmadi, V., Abuzade, R. A. & Montazer, M. Enhanced ultraviolet-protective textiles based on reduced graphene oxide-silver nanocomposites on polyethylene terephthalate using ultrasonic-assisted in-situ thermal synthesis. J. Appl. Polymer Sci. 139(21), 52196 (2022).

-

Erol, I. et al. Synthesis of Moringa oleifera coated silver-containing nanocomposites of a new methacrylate polymer having pendant fluoroarylketone by hydrothermal technique and investigation of thermal, optical, dielectric and biological properties. J. Biomater. Sci.-Polymer Edition 33(10), 1231–1255 (2022).

-

Bekhit, M., El-Sayyad, G. S. & Sokary, R. Gamma radiation-induced synthesis and characterization of decahedron-like silver nanostructure and their antimicrobial application. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym Mater. 33(9), 2906–2923 (2023).

-

Saxena, I., S.M. Ejaz, and A. Gupta, Synthesis characterization and application of butyl acrylate mediated eco-friendly silver nanoparticles using ultrasonic radiation. Heliyon 10(7), (2024).

-

El-Sheikh, M. A. et al. A novel method for the preparation of conductive methyl cellulose-silver nanoparticles-polyaniline-nanocomposite. Egypt. J. Chem. 63(9), 3567–3582 (2020).

-

El-Naggar, M.E.-S., Synthesis, Characterization and Medical Applications of Nano-Starch. M.E.-S. El-Naggar, Editor. Scholars’ Press, Germany. p. 388 (2015).

-

Hebeish, A. et al. Antimicrobial wound dressing and anti-inflammatory efficacy of silver nanoparticles. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 65, 509–515 (2014).

-

Hebeish, A. et al. Nanostructural features of silver nanoparticles powder synthesized through concurrent formation of the nanosized particles of both starch and silver. J. Nanotechnol. 2013, 1–10 (2013).

-

El-Sheikh, M. A. et al. Green synthesis of hydroxyethyl cellulose-stabilized silver nanoparticles. J. Polymers 2013, 1–11 (2013).

-

El-Sheikh, M. A. Novel curcumin-silver nanoparticles-methyl cellulose nanocomposite, perparation, characterization, and medical applications. In ACS Fall 2023 (ed. El-Sheikh, M. A.) (American Chemical Society Meetings and Events, 2023).

-

El-Sheikh, M. A. Novel cinnamon-methyl cellulose-silver nanocomposite, preparation, characterization, and cotton fabric finishing. In ACS Fall 2023 (ed. El-Sheikh, M. A.) (American Chemical Society Meetings and Events, 2023).

-

El-Sheikh, M. A. Synthesis of a novel carboxymethyl chitosan-silver nanoparticles- ginger nanocomposite. In ACS Fall 2022 (ed. El-Sheikh, M. A.) (American Chemical Society Meetings and Events, 2022).

-

El-Sheikh, M.A., A Novel Photosynthesis of Carboxymethyl Starch-Stabilized Silver Nanoparticles: Experimental Investigation, in Innovations in Science and Technology Vol. 4, A.K. Goel, Editor. B P International: UK. p. 69–83 (2022).

-

Ragab, H. M. et al. Fabrication and characterization of silver nanoparticle-doped chitosan/carboxymethyl cellulose nanocomposites for optoelectronic and biological applications. ACS Omega 9(20), 22112–22122 (2024).

-

Mohandoss, S. et al. Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of silver nanoparticle-loaded carboxymethyl chitosan with sulfobetaine methacrylate hydrogel nanocomposites for biomedical applications. Polymers (Basel) 16(11), 1513 (2024).

-

Zhang, C. Y. & Li, X. X. Cellulose-based seedless synthesis of silver nanowires and their application as sensitive SERS. Mater. Lett. 372, 136990 (2024).

-

Srikhao, N. et al. Green synthesis of nano silver-embedded carboxymethyl starch waste/poly vinyl alcohol hydrogel with photothermal sterilization and pH-responsive behavior. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 242, 125118 (2023).

-

Yang, X. Q. et al. Green synthesis of Poria cocos polysaccharides-silver nanoparticles and their applications in food packaging. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 269, 131928 (2024).

-

Saruchi, et al., Synthesis and antibiofilm activity of silver nanoparticles fabricated sodium alginate-based nanocomposite film. Bionanoscience, 2024. 14(2): 1132–1140.

-

Khatami, M. et al. Cockroach wings-promoted safe and greener synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their insecticidal activity. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 42(12), 2007–2014 (2019).

-

Ilickas, M. et al. UV-mediated photochemical synthesis and investigation of the antiviral properties of Silver nanoparticle-polyvinyl butyral nanocomposite coatings as a novel antiviral material with high stability and activity. Appl. Mater. Today 38, 102203 (2024).

-

Chutrakulwong, F., Thamaphat, K. & Intarasawang, M. Investigating UV-irradiation parameters in the green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from water hyacinth leaf extract: Optimization for future sensor applications. Nanomaterials 14(12), 1018 (2024).

-

Cheng, D. et al. Novel method for the preparation of polymeric hollow nanospheres containing silver cores with different sizes. Chem. Mater. 17(14), 3578–3581 (2005).

-

El-Sheikh, M. A. Synthesis of a novel carboxymethyl chitosan-silver – ginger nanocomposite, characterization, and antimicrobial efficacy. Carbohyd. Polymer Technol. Appl. 8, 100561 (2024).

-

El-Sheikh, M. Novel curcumin-silver nanoparticles-methyl cellulose nanocomposite, preparation, characterization, and medical applications. (2023).

-

Abdel-Monem, R. A. et al. Antibacterial properties of carboxymethyl chitosan Schiff-base nanocomposites loaded with silver nanoparticles. J. Macromol. Sci. A 57(2), 145–155 (2020).

-

Qi, Z. et al. In situ synthesis of silver nanoparticles onto cotton fibers modified with carboxymethyl chitosan. Integr. Ferroelectr. 208(1), 10–16 (2020).

-

Lv, J. et al. Preparation and properties of polyester fabrics grafted with O-carboxymethyl chitosan. Carbohyd. Polym. 113, 344–352 (2014).

-

Alhashmi Alamer, F. The effects of temperature and frequency on the conductivity and dielectric properties of cotton fabric impregnated with doped PEDOT:PSS. Cellulose 25(10), 6221–6230 (2018).

-

Dahl, J. A., Maddux, B. L. S. & Hutchison, J. E. Toward greener nanosynthesis. Chem. Rev. 107(6), 2228–2269 (2007).

-

Aldebasi, M. et al. Photochemical synthesis of noble metal nanoparticles: Influence of metal salt concentration on size and distribution. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 14018. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms241814018 (2023).

-

Jara, N. et al. Photochemical synthesis of gold and silver nanoparticles-a review. Molecules 26(15), 4585 (2021).

-

El-Sheikh, M. A. A novel photosynthesis of carboxymethyl starch-stabilized silver nanoparticles. ScientificWorldJournal 2014, 514563 (2014).

-

Tzaneva, D. et al. Synthesis of carboxymethyl chitosan and its rheological behaviour in pharmaceutical and cosmetic emulsions. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 7(10), 70–78 (2017).

-

AATCC Test Method 147–2004. 2010: NC 27709.

-

Chen, X.-G. & Park, H.-J. Chemical characteristics of O-carboxymethyl chitosan related to its preparation conditions. Carbohy. Polymers 53, 355–359 (2003).

-

El-Sheikh, M. A., El Gabry, L. K. & Ibrahim, H. M. Photosynthesis of carboxymethyl starch-stabilized silver nanoparticles and utilization to impart antibacterial finishing for wool and acrylic fabrics. J. Polymers 2013, 792035 (2013).

-

Hebeish, A. A. et al. Carboxymethyl cellulose for green synthesis and stabilization of silver nanoparticles. Carbohyd. Polym. 82(3), 933–941 (2010).

-

El-Sheikh, M. A novel photosynthesis of carboxymethyl starch-stabilized silver nanoparticles. TheScientificWorldJOURNAL 2014, 514563 (2014).

-

El-Sheikh, M. A. A novel photosynthesis of carboxymethyl starch-stabilized silver nanoparticles. Sci. World J. 2014, 514563 (2014).

-

El-Sheikh, M. A novel photo-grafting of acrylamide onto carboxymethyl starch. 1. Utilization of CMS-g-PAAm in easy care finishing of cotton fabrics. Carbohyd. Polymers 152, 105–18 (2016).

-

Ndikau, M. et al. Green synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Citrullus lanatus fruit rind extract. Int. J. Anal. Chem. 2017, 8108504 (2017).

-

Wei, D. & Qian, W. Facile synthesis of Ag and Au nanoparticles utilizing chitosan as a mediator agent. Colloids Surf. B 62(1), 136–142 (2008).

-

Liu, B. et al. Facile and green synthesis of silver nanoparticles in quaternized carboxymethyl chitosan solution. Nanotechnology 24(23), 235601 (2013).

-

Huang, S. et al. Quaternized carboxymethyl chitosan-based silver nanoparticles hybrid: Microwave-assisted synthesis, characterization and antibacterial activity. Nanomaterials (Basel) 6(6), 118 (2016).

-

Montazer, M. & Morshedi, S. Nano photo scouring and nano photo bleaching of raw cellulosic fabric using nano TiO2. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 50(4), 1018–1025 (2012).

-

Dastjerdi, R. & Montazer, M. A review on the application of inorganic nano-structured materials in the modification of textiles: Focus on anti-microbial properties. Colloids Surf. B 79(1), 5–18 (2010).

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

El-Sheikh, M.A., Abdeldayem, S.A. A novel photo-induced synthesis of carboxymethyl chitosan-silver nanocomposite: preparation, characterization and antibacterial efficacy of cotton finished fabrics. Sci Rep 16, 5347 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34277-9

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

Version of record:

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34277-9