Introduction

RNA therapy refers to a therapeutic approach that utilizes ribonucleic acid (RNA) molecules to treat diseases. It involves the use of various types of RNA molecules, such as messenger RNA (mRNA), small interfering RNA (siRNA), microRNA (miRNA), and antisense RNA, to regulate gene expression, protein production, or other cellular processes involved in disease pathology. RNA therapy can be used to target a wide range of conditions, including genetic disorders, infectious diseases, cancer, and autoimmune disorders. The primary goal of RNA therapy is to modulate gene expression or protein activity, thereby correcting aberrant cellular functions and restoring health.

RNA-based therapies represent a promising class of treatments that harness the cellular machinery to address various diseases at the genetic level. RNA-based therapies hold great promise for revolutionizing disease treatment by offering more effective, precise, and personalized interventions. These therapies enable the accurate targeting of disease-causing genes or proteins, offer versatility across various disease mechanisms, and facilitate rapid development compared to traditional drugs. With reduced immunogenicity compared to viral vectors, these novel therapeutic approaches foster innovation and advancement in medicine. In this review, the term ‘RNA therapeutics’ refers to agents in which RNA molecules function as the therapeutic entity itself (e.g., siRNA, miRNA, mRNA vaccines, antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs), or aptamers), whereas ‘RNA-based therapeutics’ includes both RNA therapeutics and RNA-dependent technologies such as CRISPR–Cas systems and RNA-guided editing tools. This distinction is important for delineating direct RNA drug modalities from RNA-utilizing therapeutic platforms1. In recent years, RNA-based therapies have emerged as a groundbreaking approach in medicine, offering innovative solutions to various diseases by leveraging the inherent capabilities of RNA molecules within the human body.

Historical evolution of RNA-based therapeutics

RNA therapy is now a vital tool for treating human diseases, as evidenced by several recent discoveries. When Crick first described RNA in his groundbreaking paper, “Central Dogma of Molecular Biology,” it became clear that RNA was essential to transmitting genetic information2. The subsequent identification of mRNA provided conclusive evidence, further underscoring the critical role of these molecules as essential messengers in genetic information translation3,4.

Another significant, yet less discussed, breakthrough in the realm of RNA research was the discovery that two RNA molecules form base pairs with each other. This discovery, now commonly accepted, challenged early assumptions that RNA could not adopt a double helix structure. In 1956, Rich and Davies published pioneering work on nucleic acid hybridization reactions, demonstrating that RNA could indeed form a structure akin to DNA through complementary base pairing5. This seminal finding laid the groundwork for subsequent discoveries, such as microRNAs in 1993 and RNA interference in 1998. In both cases, the formation of RNA duplexes plays a crucial role in RNA silencing mechanisms6,7.

The first use of RNA base pairing for therapeutic purposes was described by Stephenson and Zamecnik in 1978. They created an ASO that was intended to target the Rous sarcoma virus (RSV) 35S RNA sequence to hinder viral multiplication8. This pioneering work laid the foundation for RNA-based therapeutics. Nearly two decades later, the United States Food and Drug Administration (US FDA) sanctioned the first drug employing an ASO for the treatment of cytomegalovirus retinitis9.

RNA splicing, a post-transcriptional process that connects exons and eliminates introns from primary RNA transcripts, was initially discovered in 197710. It is now recognized as a key mechanism in disease, with alterations in splicing being associated with numerous human disorders10,11,12. While traditionally considered challenging with conventional small-molecule drugs, modulation of splicing defects has now been shown to be feasible through both RNA-targeting small molecules and RNA-based therapeutics. A notable example is risdiplam, a small-molecule splicing modulator approved by the FDA in 2020 that promotes the inclusion of exon 7 in SMN2 transcripts to treat spinal muscular atrophy (SMA)13.

In parallel, ASOs such as nusinersen and eteplirsen have demonstrated that targeted manipulation of pre-mRNA splicing can correct disease-associated defects at the transcript level14. The first experimental evidence of antisense-mediated splicing correction was reported by Dominski and Kole (1993), who restored β-globin splicing in a β-thalassemia model, establishing the conceptual foundation for modern splice-modulating RNA therapies15. Correcting or adjusting splicing defects is nearly impossible with traditional small-molecule drugs, but it can be achieved using RNA-based therapies, particularly ASOs. A 1993 study was the first to demonstrate that alternative splicing could be influenced through the use of ASOs15. In this research, a group of ASOs was employed to target the splice sites and branch points of thalassaemic pre-mRNA, aiming to correct abnormal splicing and alleviate symptoms. This work now stands as a foundational reference in advancing new treatments for various challenging neurological disorders16.

Compared to the prolonged evolution of antisense oligo-based drugs, the transition from the discovery of small interfering RNAs to their practical use as therapeutic medications occurred relatively quickly. The concept of RNA interference was initially elucidated in a groundbreaking paper in 1998, demonstrating that the administration of sense and antisense RNAs to Caenorhabditis elegans embryos effectively and specifically inhibited targeted endogenous mRNAs7. Due to its simplicity and efficacy, RNAi gained rapid acceptance within the scientific community and saw extensive application in a remarkably short period. An illustrative example is a study from 2002 that showcased the use of RNAi to suppress hepatitis C virus replication in mice, leading to widespread exploration of RNAi for therapeutic purposes16. This impetus led to the first RNAi technology-based clinical trials, which began in 2010, when a patient with extensive melanoma received a siRNA targeting the M2 subunit of ribonucleotide reductase.

Notably, this trial demonstrated the successful cleavage of the target mRNA when the siRNA was delivered utilizing a targeted nanoparticle delivery system17. Following this significant achievement, other siRNA-based medications were evaluated for various illnesses; in 2018, the first siRNA medication was licensed for use in patients with hereditary transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis18. Despite mRNA being identified as a genetic translation messenger in 1961, it took nearly three decades for researchers to harness it for therapeutic purposes19. The identification of RNA-related enzymes, like RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (also called RNA replicase) and reverse transcriptase, made decades ago, has played a crucial role in the progress of today’s mRNA-based therapies20.

In the 1990s, efforts to generate specific proteins by introducing exogenous mRNA began, marking a pivotal chapter in the field of scientific exploration. Wolff and colleagues’ groundbreaking work in 1990, where they injected mRNAs for reporter genes directly into mouse skeletal muscle, laid the foundation for utilizing exogenous mRNA to express specific proteins in vivo21. This early success paved the way for exploring mRNA as a potential tool for vaccination. In 1993, mRNA transcripts were first evaluated as a vaccine when researchers synthesized mRNAs for the influenza nucleoprotein and encapsulated them into liposomes for injection into mice22. This study demonstrated the ability of mRNA vaccines to induce an immune response, specifically the production of virus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes. The potential of mRNA vaccines in cancer treatment was realized by Conry and colleagues in 1995 when they designed the first mRNA vaccine targeting human carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA)23. When injected safely into CEA-expressing tumor cells, this vaccine showed promising results in mouse models. Although initial progress was promising, it took several years for mRNA-based therapies to reach human clinical trials. It was not until 2008 that Weide and collaborators published the first clinical trial outcomes involving mRNA vaccines in patients with metastatic melanoma24. Protamine-protected mRNAs encoding tumor-associated antigens were used in these vaccines, and the outcomes demonstrated an increase in vaccine-directed T cells, suggesting a possible therapeutic benefit25. The journey from early animal experiments to human clinical trials highlights the gradual but significant progress made in harnessing the potential of mRNA for therapeutic purposes.

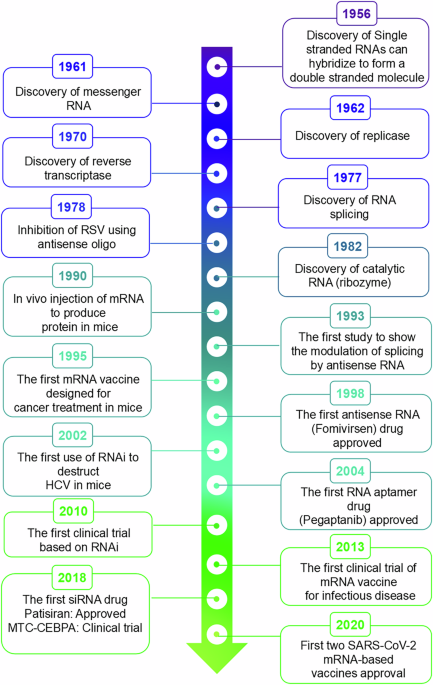

The journey of mRNA vaccines in combating infectious diseases began with a landmark clinical trial in 2013 (NCT02241135). This trial investigated a novel rabies vaccine that harnesses mRNA technology to deliver its glycoprotein. Results were promising, demonstrating the ability of the vaccine to stimulate the production of effective antibodies against the targeted viral antigens, marking a pivotal advancement in mRNA-based vaccine development26. 2020 marked a significant milestone in medical history with the approval of the first mRNA-based vaccination against the coronavirus that causes severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS-CoV-2)26. This brief description, embraced by nations worldwide, represents the culmination of over four decades of dedicated research and underscores the transformative potential of mRNA therapeutics in shaping the future of global healthcare. This concise overview highlights the extensive legacy of RNA-based therapeutics, with Fig. 1 summarizing the key historical milestones in RNA biology and therapeutic development.

Timeline highlighting major milestones in the understanding of RNA biology and the development of RNA-based therapeutic technologies.

RNA-based therapeutics and their biomechanics

Long-term research into various RNA types has led to a deeper understanding of cellular mechanisms and the rapid development of RNA-based therapies. These therapies, including ASOs, small interfering RNAs, microRNAs, and modified messenger RNAs, hold promise for modulating gene expression and treating genetic diseases27. RNA therapeutics can be broadly categorized into four main domains: antisense technologies, mRNA-based strategies, RNA interference-based therapeutics, and CRISPR–Cas-mediated genome editing. Each approach offers unique ways to treat diseases by targeting specific genes or genetic processes.

Antisense technologies

The year 1978 marked the introduction of the concept of creating oligonucleotides to bind to particular sequences within target RNAs through Watson-Crick hydrogen bonding. This concept and the term “antisense” initially represented a straightforward idea, although it lacked specificity. Double-stranded RNA was discovered by Andrew Fire and Craig Mello in 1998 to be the cause of RNA interference in Caenorhabditis elegans7. The authors did not outline specific mechanisms by which RNA binding modifies the behavior and effectiveness of the targeted RNA. Furthermore, they did not specify whether the administered drug would consist of a single or double strand, nor did they delineate the necessary chemical modifications to ensure therapeutic efficacy.

Antisense refers to any oligonucleotide, irrespective of its composition or chemical makeup, engineered to interact with target RNA through Watson-Crick hybridization. Nearly 50 years ago, Paul Zamecnik and Mary Stephenson created a synthetic ASO in 1978 with the goal of blocking the reproduction of the Rous sarcoma virus in tissue culture. This marked the beginning of the development of antisense-based treatments28. These investigations introduced the concept of leveraging the distinctive chemical attributes of nucleic acids in pharmaceutical development. Initially, this concept and the term “antisense” seemed straightforward, albeit lacking specificity. The US FDA did not approve the first ASO medication for clinical use until two decades later27.

Synthetic 21-nucleotide (nt) ASO fomivirsen inhibits the synthesis of proteins essential for CMV replication by interacting with a complementary mRNA region of the virus29. With its approval, it was intended to treat CMV retinitis, a severe infection of the retina that is common in people with acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) and can result in blindness30,31. The medicine was taken off the market despite its therapeutic benefits because anti-retroviral therapy was so successful. Nevertheless, the first demonstration of the clinical utility of ASOs was given by fomivirsen, which provided first clinical proof-of-concept for ASO despite later market withdrawal due to changing clinical practice More recent approvals (and ongoing trials, given in Table 1) highlight the importance of route-of-administration and tissue targeting for efficacy and safety: intrathecal delivery enabled CNS exposure for nusinersen, whereas systemic ASOs require careful chemistry to balance stability, protein binding, and off-target effects. Together, these trials emphasize that ASO success depends as much on delivery and patient selection as on target biology32. Progress in RNA biology has facilitated the advancement of ASOs that operate through various mechanisms after binding to RNA. These mechanisms can generally be categorized into two groups based on different post-hybridization mechanisms: those involving the degradation of target RNAs mediated by occupancy (via cleavage) and those involving only occupancy (through steric interference)33,34. ASO-mediated mechanism delineated in Fig. 2.

There are two ways that ASOs can alter the expression of a target gene. (1) In the occupancy-mediated degradation pathway, ASOs cause ribozymes or RNase H1 to cleave the target mRNA. It is not the case that the occupancy-only mechanisms directly damage target RNA. Instead, it controls the expression of genes in multiple ways: (2) causes nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD); (3) inhibits or activates translation; (4) changes RNA splicing by employing splice-switching ASOs to induce exon skipping or exon inclusion; (5) impedes the microRNAs binding to target mRNA (Created with BioRender.com).

Occupancy-mediated degradation

Occupancy-mediated degradation involves the precise binding of ASOs to specific RNA sequences, leading to the cleavage of RNA at the ASO binding sites by endogenous enzymes35. Occupancy-mediated degradation of target RNA has demonstrated effectiveness as a productive approach, with several mechanistic strategies validated for its implementation. The most thoroughly characterized mechanism is RNase H1-mediated degradation, in which RNase H1 functions as a highly selective endonuclease, cleaving RNA within double-stranded RNA: DNA hybrids. Subsequently, the RNA fragments from this process are degraded by 5’ and 3’ exonucleases. RNase H1 requires a substrate containing 8–10 consecutive ribonucleotide-containing base pairs (bp) for optimal activity. Consequently, ASOs that facilitate RNase H1-mediated degradation of the target RNA fragments typically possess a central segment composed of eight to ten deoxynucleotides, flanked by multiple 2ʹ-modified nucleotides, known as chimeric or gapmer ASOs. This structural configuration enhances the affinity of ASOs for their target RNA and increases their resistance to nucleases, thereby prolonging their activity duration. Due to its widespread presence, RNase H1 effectively targets both cytoplasmic and nuclear transcripts36. Other enzymes, such as ribozymes, also contribute to degradation through occupancy-based mechanisms37. Ribozymes cleave target RNAs using structural motifs, such as hammerhead or hairpin formations. Moreover, their substrate recognition domains can be modified to enable precise, site-specific cleavage in either a cis or trans manner38.

Occupancy-only mechanisms

In occupancy-only mechanisms, ASOs regulate the up- or downregulation of target transcripts solely through binding, independent of specific enzymes. In the occupancy-only or steric-blocking, mechanism of action, ASOs regulate RNA processing and function without inducing RNase H1-mediated cleavage39. Instead, they act by physically blocking the access of cellular machinery to specific RNA sequences. First, ASOs can bind to pre-mRNA at splice-junctions or splicing-regulatory elements, thereby preventing spliceosome assembly or altering exon recognition, resulting in modulation of exon inclusion or exclusion35. This steric interference enables the correction of aberrant splicing, as exemplified by nusinersen, which restores exon 7 inclusion in SMN2 transcripts to treat spinal muscular atrophy40. Second, ASOs may hybridize to the 5′ untranslated region (UTR) or start codon region of mRNA, blocking ribosomal recruitment and translation initiation. Third, ASOs can interfere with RNA–protein or RNA–microRNA interactions, modifying RNA stability, nuclear export, or localization. Collectively, these occupancy-only mechanisms enable RNA modulation without transcript degradation, broadening therapeutic applications for targets not amenable to RNase H1–dependent strategies41,42.

Clinical trials have examined translation-blocking ASOs, including those designed to inhibit MYC translation, as a potential treatment for cancer43. ASOs can also direct the cleavage of 5’ cap structures, thereby blocking translation44. ASOs can attach to pre-mRNA sequences associated with cleavage and polyadenylation, influencing the selection of polyadenylation sites and consequently modifying mRNA stability and levels45. The production of desirable mRNAs and their encoded proteins can be enhanced through various mechanisms.

To date, the most widely used method in developing agents that have entered clinical trials involves designing ASOs that modify splicing, such as Phosphorothioate (PS) ASOs and phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligomers46,47,48,49. A prime example is the action mechanism of nusinersen, a recognized ASO used to treat spinal muscular atrophy (SMA). This condition results from the homozygous loss of function of the SMN1 gene, which encodes the SMN protein, crucial for developing and maintaining neuromuscular junctions. Humans also have a backup SMN2 gene that can produce small amounts of full-length SMN. However, this gene carries a mutation in a splicing enhancer sequence, causing exon 7 to be skipped, leading to a shorter, unstable SMN variant. Nusinersen, a phosphorothioate (PS) ASO, targets SMN2 pre-mRNA, enhancing the inclusion of exon seven and allowing the production of the full-length protein in motor neurons within the central nervous system (CNS). This approach provides a highly effective treatment for SMA14,50.

Additionally, ASOs can influence precursor mRNA by modulating the splicing process. This is accomplished either by directly obstructing splice junctions or by inhibiting the binding of splicing regulatory proteins that promote or suppress splicing48,51. Occupancy-only ASOs can also activate the natural cell surveillance pathways that remove defective mRNAs52. In another mechanism, changes in splicing patterns can lead to the formation of mRNAs with premature stop codons, which are selectively degraded via the nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD) pathway52. ASOs can also interfere with mRNA translation by directly obstructing the process. This interference can activate the no-go decay pathway, a cellular quality control system that identifies and degrades mRNAs where ribosomes become stalled53.

Overall, the discovery of new mechanisms of action enhances the versatility of antisense technology. Having multiple pathways to degrade target RNAs enables effective reduction of RNA levels, even for those that are less susceptible to RNase H1-mediated cleavage, such as RNAs with very short half-lives or high translation rates54. Integrating mechanisms that selectively boost protein translation indicates that this technology can now do more than simply promote alternative splicing in individuals with loss-of-function mutations.

Limitations

Delivering ASOs in clinical applications presents several challenges, including vulnerability to degradation by serum nucleases, rapid renal clearance, limited tissue penetration, and low cellular uptake. The widely used phosphorothioate backbone improves binding with serum proteins, helping to decrease renal clearance55. Additionally, chemical modifications enhance cellular uptake by engaging surface receptors that facilitate oligonucleotide endocytosis. However, once inside the cell, ASOs need to escape the endosome to exert their activity, posing an additional challenge56.

Another challenge facing ASO therapeutics lies in their tendency to provoke immune responses. The human immune system is adept at identifying single-stranded and double-stranded RNA through pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs)57,58. Recognition of RNA occurs extracellularly via endosomal Toll-like receptors (TLRs), particularly TLR-3, 7, and 859. Cytoplasmic defense systems, including protein kinase R (PKR), oligoadenylate synthases (OASes), and RIG-I-like receptors, are responsible for detecting intracellular pathogens60. These pathways can be activated, leading to RNA degradation, disruption of cellular translation, and inflammatory responses. Synthetic RNA therapies commonly incorporate 2′-ribose and base modifications such as 2′-O-methyl, 2′-O-methoxyethyl, and 5-methylcytosine (m⁵C), to enhance nuclease resistance, reduce immunogenicity, and improve pharmacokinetic stability35,61.

Advancements in understanding the molecular processes that govern the efficacy, spread, cellular absorption, and adverse effects of ASOs provide a foundation for tailoring this adaptable technology to various ailments. Even though all ASO medications currently sanctioned are designated for individuals with uncommon illnesses, innumerable ASOs undergoing clinical trials aim to address prevalent conditions like cardiovascular diseases, metabolic disorders, and cancer. Although achieving broad application encounters obstacles, such as delivering ASOs to specific cell types and the risk of adverse effects with prolonged administration, ASO treatments are anticipated to significantly impact numerous diseases that currently lack effective treatment options.

RNAi-based therapeutics

In Caenorhabditis elegans, double-stranded RNA initiates RNA interference, as Andrew Fire and Craig Mello determined in 19987. RNAi, a natural cellular process, initiates the breakdown of particular RNA targets upon detecting double-stranded (ds) RNAs. This process acts as an inherent defense mechanism against invading viruses and transposable elements27. Their findings challenged the prevailing belief that antisense RNAs function by directly binding to inhibit the expression of target mRNA. Consequently, an enzymatic mechanism was revealed. The cytoplasmic RNase III enzyme Dicer processes double-stranded RNAs, whether endogenously produced or externally delivered as precursor RNAs with stem-loop or short hairpin structures, into small interfering RNAs or microRNAs. These small RNAs guide the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), a ribonucleoprotein assembly comprising an Argonaute protein and the siRNA or miRNA, to regulate specific target mRNAs. This Argonaute protein, along with other complex components, serves as the effector molecule. Conversely, miRNAs typically engage with partially complementary targets, resulting in translational repression and degradation of transcripts62. The RNAi pathway in human cells demonstrates exceptional efficiency due to the ability of RISC to trigger several rounds of RNA cleavage63. RNAi-based therapies capitalize on this characteristic, as well as the flexibility and controllability of the RNAi machinery. However, the necessity to involve this machinery also imposes limitations on the design of siRNA drugs. RNAi-mediated gene regulation is represented in Fig. 3.

Long double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) and precursor microRNA (pre-miRNA) are processed by Dicer into short interfering RNA (siRNA). The antisense strand of siRNA (a blue strand) is incorporated into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), which targets RNA for degradation or inhibits translation (Created with BioRender.com).

RNAi has rapidly progressed from concept to clinic with several successful examples that illustrate how delivery chemistry determines clinical use. Patisiran, delivered in lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), produced a clinically meaningful improvement in neuropathy in hereditary transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis (APOLLO trial), establishing intravenous LNP delivery for liver-targeted siRNA. Subsequent GalNAc-conjugated siRNAs (e.g., givosiran for acute hepatic porphyria and inclisiran for PCSK9/LDL-C lowering) demonstrated that receptor-mediated subcutaneous dosing enables potent, durable hepatic silencing with improved dosing convenience. The spectrum of clinical outcomes from systemic IV LNP to subcutaneous GalNAc conjugates highlights a central translational lesson: matching the delivery modality to target organ biology (liver vs extrahepatic) can make the difference between a trial failure and regulatory approval.

Synthetic RNAi triggers are typically made up of perfectly matched double-stranded RNAs that must be split apart so that one strand can serve as a “guide” for loading into RISC. In RNA interference drug design, selecting the appropriate strand is crucial, as only the antisense strand binds to the target mRNA. siRNAs that have a 2-nt 3’ overhang on one side and a blunt end on the other, for example, seem to favor the selection of the strand that has the overhang64. Additionally, chemical modifications can also facilitate the loading of the antisense strand65. Dicer is required to cleave and transmit RNAi triggers longer than 21 bp to the RISC complex. It is noteworthy that Dicer processing is linked to a more stable choice of the antisense strand, as the RISC guide66. Shorter siRNAs avoid the early stages of the RNAi pathway and can be directly inserted into RISC. This has the benefit of reducing the disruption of gene regulation by native miRNAs.

In 2018, the FDA approved the first treatment based on RNA interference-mediated gene silencing. An effective treatment for hereditary transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis (hATTR) is patisiran, a double-stranded small interfering RNA. This is the progressive neurodegeneration triggered by amyloid fibril buildup from misfolded transthyretin protein. Patisiran suppresses transthyretin mRNA in the liver, thereby reducing protein levels in the bloodstream and mitigating amyloid deposition. It comprises two modified 21-mer oligonucleotides enclosed within a lipid nanoparticle optimized for liver cell absorption. Vutrisiran, succeeding patisiran, entered the market in 2022. It operates on the exact RNAi mechanism but leverages advanced stabilization chemistry. This siRNA is linked to N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc), enhancing its absorption in liver cells and enabling lower dosage administration18. While patisiran requires an intravenous infusion every 3 weeks, vutrisiran treatment involves just one subcutaneous injection every 3 months. The FDA has approved RNAi-based drugs (Table 2), and the extensive array of oligonucleotide drugs in clinical stages suggests RNAi therapeutics will soon find widespread application. For instance, various approaches are under exploration for achieving extrahepatic delivery, including antibody conjugates67,68,69, peptide conjugates70, hydrophobic71 or lipophilic conjugates72, as well as multivalency73. Moreover, programmable siRNA pro-drugs, activated in response to specific cellular RNA biomarkers, hold promise for selectively targeting diseased cells over healthy neighboring tissue74.

miRNAs play a pivotal role as gene regulators, impacting various physiological processes associated with disease, hence emerging as promising therapeutic targets in this regard75. Unlike strict matching, miRNAs require only partial complementarity to recognize their targets. As a result, a single miRNA can bind to many different mRNAs, each with varying levels of affinity. Adjusting or mimicking miRNA activity enables the simultaneous alteration of complex gene expression networks. Although targeting multiple potentially compensatory pathways can be advantageous, it also carries the risk of unintended side effects. miRNA therapeutics are divided into two major parts: miRNA mimics and anti-miRNAs.

miRNA mimics

miRNA mimics are synthetic oligonucleotide duplex molecules designed to mimic the function of endogenous miRNAs. When introduced into cells, miRNA mimics can restore or enhance the activity of specific miRNAs that may be deficient or underexpressed in certain diseases. Once inside the cell, miRNA mimics interact with the cellular RNA interference machinery and are incorporated into the RISC. This allows them to regulate gene expression by binding to target mRNAs and inhibiting their translation or promoting their degradation, similar to natural miRNAs. miRNA mimics hold potential for therapeutic intervention in diseases where the dysregulation of specific miRNAs contributes to pathology. They can augment the activity of tumor-suppressive miRNAs in cancer or restore miRNA function in other diseases.

Anti-miRNAs

Anti-miRNAs, also known as anti-miRNA oligonucleotides (AMOs), are synthetic molecules designed to inhibit the activity of specific endogenous miRNAs. Anti-miRNAs typically function by complementary base pairing with the miRNA, sequestering it and preventing its interaction with target mRNAs. This can occur through various mechanisms, including steric hindrance, RNase H-mediated degradation, or sequestration into subcellular compartments. Miravirsen, an anti-miRNA therapy, targets miR-122, a liver-specific miRNA crucial for lipid metabolism and the replication of Hepatitis C virus (HCV). By binding to miR-122, miravirsen disrupts its interaction with HCV RNA, hindering viral replication76. Despite promising antiviral effects in trials, the rise of potent antiviral treatments for HCV reduced the clinical demand for miravirsen, leading to its recent discontinuation77.

Limitations

ASOs and siRNA medications have comparable delivery, stability, and immunogenicity issues. Thankfully, siRNA treatments benefit significantly from the advances in backbone, base, and sugar alterations that were first developed for ASO medicines61. Furthermore, while duplex siRNAs are larger and more hydrophilic than single-stranded ASOs, their delivery is more complex because their external-facing phosphate groups cause them to be rapidly excreted. In response, scientists have developed targeted ligands and lipid nanoparticles as delivery vehicles, and chemical optimization techniques are improving modified siRNA design to increase the therapeutic utility of RNA interference78.

mRNA therapeutics

The discovery of mRNA-encoded drugs emerged in the 1990s, with the revelation that directly injecting in vitro transcribed (IVT) mRNA into the skeletal muscle of mice resulted in the expression of encoded proteins21. Using bacteriophage RNA polymerase, synthetic mRNAs used in therapeutic settings are typically IVT from a DNA plasmid. They have parts like a 5’ cap, a 5’ UTR, an open reading frame (ORF), a 3’ UTR, and a poly(A) tail, and they mimic cellular mRNAs. These components are essential for the stability and translation of mRNA, which in turn affects the success of mRNA therapy. Preclinical investigation of IVT mRNA has accelerated the development of mRNA-based vaccines to fight infectious illnesses and cancer79. Modified nucleosides, such as pseudouridine and N1-methylpseudouridine, are frequently incorporated into the mRNA structure to optimize translation. Incorporating these modified nucleosides, especially modified uridine, enhances translation efficiency and shields the IVT mRNA from detection by the innate immune system. This strategy enables higher dosage levels to be administered effectively80.

Mechanistically, mRNA vaccines administered through injection enter the cytoplasm of host cells, typically antigen-presenting cells (APCs), where they are translated into specific antigens. These antigens are then presented on the surface of APCs by major histocompatibility complexes (MHCs), triggering both B cell/antibody-mediated humoral immunity and CD4+ T/CD8+ cytotoxic T-cell-mediated immunity81. Additionally, injected mRNA encoding immune stimulants like cytokines and chemokines can enhance APC maturation and activation, thereby fostering a T-cell-mediated response and improving the immune landscape within tumor microenvironments82. The FDA has approved mRNA vaccines (Table 3), and the extensive array of mRNA in clinical stages suggests these vaccines will soon find widespread application.

Early attempts to use IVT mRNA for medicinal purposes helped generate highly effective SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines quickly. Early attempts to use IVT mRNA for medicinal purposes helped to generate highly effective SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines81. Before the end of 2019, several preclinical and clinical investigations had demonstrated the potential of mRNA vaccines to protect against a range of diseases, including the rabies virus, influenza A virus, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), and Zika virus. But it was expected to take another 5–6 years before an mRNA vaccine was approved for use in clinical settings81. This process was accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic, which led to the approval of mRNA vaccines created by Moderna and BioNTech/Pfizer in just 10 months. These vaccines transmit nucleoside-modified mRNA encoding the viral spike glycoprotein. They are made with ionizable LNPs. Studies with patients showed success rates of over 90%. There were brief local and systemic reactions, but no serious safety issues83,84. However, continued assessment is crucial to address potential long-term effects. Early attempts to utilize IVT mRNA for therapeutic purposes paved the way for the rapid development of highly efficient mRNA vaccines against SARS-CoV-281. The mechanism of mRNA vaccines is represented in Fig. 4.

(1) The mRNA vaccine is delivered into antigen-presenting cells by lipid nanoparticle (LNP). (2)The mRNA encoding the disease-targeted spike protein is released into the cytoplasm and translated into the antigen protein by the ribosome. (3) Some antigen proteins are degraded into small peptides by the proteasome and presented to the surface of CD8+ T cells by major histocompatibility complex I (MHCI). The CD8+ cytotoxic T-cell-mediated immunity kills infected cells by secreting perforin or granzyme. (4) Other antigen proteins are degraded in the lysosome and displayed on the surface of T helper cells by MHC II. The B-cell/antibody-mediated humoral immunity uses antibodies to neutralize pathogens(Created with BioRender.com).

mRNA vaccines are typically administered via a single injection into the skin, muscle, or subcutaneous space, where they induce an immune response by producing antigens through translation in immune or non-immune cells. Unlike plasmid DNA and viral DNA vectors, IVT mRNA does not require entry into the nucleus to be effective. The immune system has high sensitivity, enabling strong immune responses even with low antigen levels and eliminating the necessity for high and sustained IVT mRNA expression. The mRNA platform offers various advantages for pandemic vaccine production, including rapid development and cost-effective, scalable production, allowing quick responses to emerging pandemic viruses. Additionally, it permits flexible antigen design and the delivery of multiple antigens in a single formulation, facilitating the creation of “universal” vaccines that provide broad protection against diverse viral strains. Despite the need for further development in regulatory and approval processes for mRNA vaccines, more mRNA vaccines for infectious diseases are expected to emerge in the near future.

Another exciting use of mRNA vaccines is in personalized cancer therapy, where current clinical trials show promise in triggering immune responses against cancer-specific neoantigens, with initial results suggesting potential clinical advantages85,86,87. These vaccines are customized for each patient using RNA sequencing data from their tumor tissue, enabling the immune system to specifically recognize and attack cancer cells88. Additionally, mRNA vaccines also hold promise for treating autoimmune diseases by selectively dampening harmful autoimmune reactions without affecting normal immune activity. This is accomplished by systemically delivering mRNA that encodes specific autoantigens associated with the disease89. However, challenges persist in utilizing therapeutic mRNA to express proteins that are absent or dysfunctional in the body, including the necessity for sustained protein expression, difficulties in delivering mRNA to solid organs, and the potential for immune activation and reduced therapeutic effectiveness with repeated dosing. Despite these challenges, some clinical studies, such as the use of VEGF mRNA for cardiac regeneration, have shown promising safety and efficacy outcomes90.

The emergency use and subsequent approvals of mRNA vaccines BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 provided the strongest clinical validation of IVT mRNA platforms, demonstrating high efficacy and acceptable short-term safety in large randomized trials and enabling rapid scale-up of GMP manufacturing. Beyond infectious disease, early-phase clinical work now explores mRNA for regenerative and oncologic applications: intramyocardial VEGF-A mRNA (AZD8601) was safely administered during cardiac surgery and showed encouraging biological signals in Phase I/II work, supporting tissue-targeted protein replacement strategies. Personalized neoantigen mRNA vaccines indicate the feasibility of individualized mRNA cancer vaccines that induce tumor-specific T-cell responses and can be integrated with standard therapies in early trials. These examples collectively show that mRNA therapeutics are moving steadily from prophylactic vaccines toward therapeutics that demand precise delivery, patient-specific manufacture, and careful immune-monitoring.

CRISPR-Cas-mediated genome editing

In their natural environment, bacteria and archaea utilize RNA-guided endonucleases from various CRISPR-associated protein (Cas) systems to recognize and cleave foreign nucleic acids as part of their adaptive immune system91. These systems maintain a memory of previously encountered pathogens by storing nucleic acid sequences captured during past infections, which are then employed as “spacer sequences” to guide CRISPR–Cas proteins in targeting and destroying the DNA or RNA of future pathogens (as represented in Fig. 5). This mechanism allows CRISPR–Cas systems to be easily reprogrammed to target diverse DNA or RNA sequences by utilizing different spacer sequences within a guide RNA molecule, provided that the corresponding target DNA “protospacer” sequence is located adjacent to a suitable Protospacer-Adjacent Motif (PAM)92,93. A PAM is necessary to safeguard the genomic DNA containing guide RNA sequences from destruction by CRISPR–Cas systems, as these sequences include targeted spacers but lack adjacent PAM sequences91.

The CRISPR/Cas RNA editing system involves two types of Cas nucleases: Cas9 and Cas13. A guide RNA (gRNA) is associated with Cas9 to cut ssRNA either with (1) or without (2) the need for a protospacer-adjacent motif (PAM). (3) Cas13 is directed by a single CRISPR RNA (crRNA) to target specific RNA containing a protospacer flanking sequence (PFS). (4) Beyond knocking down target RNA, a catalytically inactive Cas13b (dCas9b) enables A-to-I editing with the help of ADAR (Created with BioRender.com).

The Cas systems, originally derived from prokaryotes, have found widespread use in mammalian cells and organisms for precise genome editing, leading to the permanent knockout or alteration of a targeted gene. This system operates through a designed guide RNA (gRNA) and an RNA-guided Cas nuclease, where the gRNA forms a complex with Cas, recognizing a specific sequence along with a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) element. Subsequently, the Cas nuclease cleaves either double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) or single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) at the designated site for efficient genome editing94. Initial successes have spurred the development of novel methods for nucleic acid targeting and manipulation, including those derived from Cas9 and Cas13 orthologs95. The Cas9 system, for example, can target both double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) and single-stranded RNA (ssRNA), requiring a corresponding guide RNA (gRNA) and a complementary PAM-containing oligonucleotide (PAMmer) specific to Streptococcus pyogenes RCas996.

Moreover, Cas9 orthologs from organisms like Campylobacter jejuni and Staphylococcus aureus possess the ability to cleave ssRNA without the need for a PAM97. Additionally, Cas13-based systems specifically target RNA, using a CRISPR RNA (crRNA) to direct the cleavage process. Different Cas13 variants, including Cas13a, Cas13b, and Cas13d, have been shown to effectively disrupt and silence target RNAs in mammalian cells in vitro, with CasRx (RfxCas13d) displaying especially strong RNA knockdown efficiency in HEK293T cells98. Additionally, Cas13b, in a catalytically inactive form, can promote A-to-I base conversion by fusing with the ADAR2 deaminase domain (ADAR2DD), whereas Cas13d provides a unique PFS-independent Cas variation99. The list of CRISPR/Cas9-based therapies that have received FDA approval or are undergoing clinical evaluation is provided in Table 4.

Limitations

Technical constraints and advancements in CRISPR technologies have raised concerns regarding immunogenic toxicity. A recent study revealed that many human subjects possessed pre-existing antibodies against Cas9, a commonly used bacterial nuclease. Specifically, more than 50% of the subjects exhibited immunity against two extensively studied nucleases, SaCas9 and SpCas9, which are prevalent in human blood, eliciting an immunogenic response100. These findings underscore the importance of conducting thorough investigations, particularly in vivo gene therapy applications. Moreover, the guide RNA (gRNA) can trigger an innate immune response in human cells due to a phosphate group at the 5’ terminal101. Although CRISPR has been extensively utilized in clinical trials to modify somatic cells ex vivo, aiming to mitigate risks before transferring them for in vivo gene therapy, ethical challenges persist in germ-line gene editing studies for therapeutic purposes. Consequently, ongoing and upcoming clinical trials on somatic CRISPR therapy require careful long-term evaluation to comprehensively assess system efficacy and safety.

CRISPR technologies have rapidly advanced from preclinical promise to clinical reality. Ex vivo editing programs (for example, CTX001/exa-cel, now marketed as Casgevy) that edit autologous hematopoietic stem cells have shown transformative outcomes in sickle cell disease and transfusion-dependent β-thalassemia, demonstrating durable clinical benefit but also highlighting logistical and manufacturing complexities inherent to cell-based gene editing. In vivo programs (e.g., EDIT-101 for LCA10) have delivered CRISPR payloads directly to target tissues and shown early signs of biological activity with acceptable safety profiles, illustrating the feasibility of local in vivo editing. These clinical case studies reveal common translational constraints manufacturing scale, delivery specificity, pre-existing anti-Cas immunity, and long-term follow up that must be addressed as RNA-guided editing moves toward broader clinical deployment.

A notable limitation of genome-editing approaches lies in the inherent instability of mRNA molecules encoding large CRISPR/Cas systems. The substantial size of CRISPR-associated nuclease transcripts, such as SpCas9, significantly influences their susceptibility to degradation and poses challenges for efficient delivery and translation in target cells102. Larger mRNA constructs are more prone to enzymatic breakdown, demonstrate reduced encapsulation efficiency within lipid or polymeric nanocarriers, and often exhibit limited in vivo stability103. Moreover, simultaneous delivery of nuclease mRNA with guide RNA or repair templates further complicates formulation design and dosing strategies. To address these challenges, recent studies have explored the development of compact Cas variants (e.g., SaCas9, Cpf1), split-Cas systems, and optimized nanocarrier formulations that enhance mRNA protection and intracellular release104. Despite these advances, ensuring mRNA stability and delivery efficiency for large CRISPR constructs continues to represent a major barrier to the successful clinical translation of mRNA-based genome editing therapies105.

Delivery strategies for RNA-based therapeutics

Overcoming biological barriers is crucial for efficiently delivering RNA-based therapeutics, which face numerous challenges in reaching their intended targets. Thus, here is an elaboration on strategies aimed at addressing these challenges and fostering innovations in RNA delivery.

Enhanced stability

RNA molecules are inherently unstable and prone to degradation by nucleases present in bodily fluids106. To mitigate this limitation, extensive research has focused on chemical and structural optimization of RNA molecules. Incorporation of nucleoside modifications such as 2′-O-methyl, 2′-fluoro, pseudouridine, and N1-methyl-pseudouridine has been shown to markedly enhance resistance to enzymatic hydrolysis while simultaneously improving translational efficiency107. Similarly, optimizing RNA secondary structure and codon usage using computational tools such as LinearDesign has proven effective in prolonging mRNA half-life and increasing protein expression without introducing new immunogenic motifs108. Beyond intrinsic modifications, encapsulation of RNA within protective carriers such as LNPs, lipid-polymer hybrids, or biodegradable polymers provides a steric shield against nuclease attack. These carriers maintain molecular integrity during systemic circulation and facilitate controlled release at the target site109. Surface modification with hydrophilic polymers, most notably polyethylene glycol (PEG), further prevents opsonization and clearance by the mononuclear phagocyte system, thereby extending circulation time and bioavailability110.

Improved cellular uptake

Efficient intracellular delivery is another critical determinant of RNA therapeutic efficacy. Following systemic administration, nanoparticles interact with plasma proteins and are internalized by cells primarily through endocytic pathways such as clathrin-mediated or caveolae-mediated endocytosis111. However, once inside endosomes, RNA must escape into the cytoplasm before lysosomal degradation. Ionizable lipids that become positively charged in acidic environments, together with helper lipids like DOPE, enable endosomal membrane destabilization through the proton-sponge or fusion mechanism, leading to efficient cytosolic release112. Additionally, cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs) such as TAT, penetratin, and arginine-rich sequences have been explored for enhancing uptake, either through direct translocation or receptor-mediated processes113. Recent studies also highlight the importance of tuning nanoparticle surface charge and pKa: slightly cationic or near-neutral surfaces minimize non-specific protein binding while promoting efficient cellular entry114.

Targeted delivery

Targeted RNA delivery remains a major challenge yet holds the key to maximizing efficacy and minimizing systemic toxicity. Innovations in targeting ligands and receptor-mediated delivery systems enable precise localization of RNA therapeutics to desired sites within the body. By selectively targeting diseased cells or tissues, these delivery strategies enhance therapeutic efficacy while reducing systemic toxicity115. Passive accumulation through the enhanced-permeability-and-retention (EPR) effect allows nanoparticles within 50–150 nm to concentrate in tumors and inflamed tissues, although this mechanism shows variability in humans116. Active targeting employs receptor-specific ligands such as N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) for hepatocytes, folate for cancer cells, and antibodies or aptamers for precision delivery to immune or endothelial cells. For instance, GalNAc-conjugated siRNA therapeutics, including givosiran and inclisiran, have achieved clinically validated liver-specific gene silencing. Furthermore, emerging biomimetic approaches exploit the adsorption of endogenous proteins such as Apolipoprotein E (ApoE) onto LNP surfaces to promote receptor-mediated hepatic uptake. In immunotherapy applications, targeted mRNA delivery to dendritic cells via receptor-specific ligands has been shown to amplify antigen presentation and improve vaccine potency117.

Immune response

The activation of innate immune responses by RNA molecules poses a hurdle to their successful delivery. Strategies to modulate immune responses and minimize inflammatory reactions include the design of RNA molecules with reduced immunogenicity, as well as the incorporation of immunomodulatory agents into delivery systems. These innovations help circumvent immune activation, thereby improving the safety and tolerability of RNA-based therapies. The innate immune system readily recognizes exogenous RNA through pattern-recognition receptors such as TLR3, TLR7/8, and RIG-I. Activation of these pathways can lead to cytokine release, inflammation, and diminished therapeutic efficacy118. To mitigate such immune responses, modified nucleotides like pseudouridine and 5-methylcytidine are widely used to suppress TLR activation while maintaining translational competence. Encapsulation within biocompatible carriers such as LNPs and polymeric vesicles also shields RNA from immune recognition. In addition, formulations incorporating immunomodulatory agents such as dexamethasone or anti-inflammatory lipids can further reduce local inflammation and improve tolerability. Optimization of lipid composition is required to minimize complement activation or pseudoallergic reactions occasionally observed with cationic lipids119.

Biocompatibility and safety

Ensuring the biocompatibility and safety of RNA delivery systems is paramount for clinical translation. Innovations in the design of delivery vehicles focus on using biocompatible materials and minimizing cytotoxicity. Additionally, advancements in formulation techniques aim to optimize the pharmacokinetics and biodistribution of RNA therapeutics, maximizing their therapeutic potential while reducing adverse effects120. Ionizable lipids that degrade into neutral metabolites, biodegradable polymers such as poly(β-amino esters), and zwitterionic coatings are now preferred to avoid chronic tissue accumulation121. Biodegradability also mitigates hepatosplenic buildup observed after repeated dosing of conventional. Furthermore, rational design of nanoparticle pharmacokinetics, balancing circulation half-life, tissue penetration, and clearance, remains essential for achieving therapeutic efficacy without off-target toxicity. Current clinical data from mRNA vaccines and siRNA therapeutics indicate that well-optimized delivery systems can achieve high potency with acceptable safety profiles, underscoring the promise of continued material innovation in RNA medicine122.

Combination therapies

The clinical success of RNA therapeutics underscores a key translational principle: the mode of delivery largely determines the therapeutic indication. Among current platforms, ionizable LNP have been pivotal in enabling in vivo delivery of mRNA, as demonstrated by the rapid development of the COVID-19 vaccines BNT162b2 and mRNA-127383,84. These LNP efficiently encapsulate and transport mRNA into antigen-presenting cells following intramuscular injection, driving strong protein expression and robust immune responses. In contrast, N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) conjugation has proven ideal for hepatocyte-targeted siRNA drugs, such as givosiran and inclisiran, where receptor-mediated uptake via the asialoglycoprotein receptor allows potent and sustained gene silencing after infrequent subcutaneous dosing123,124.

Additionally, local delivery approaches, including intracoronary or intramyocardial administration of VEGF-A mRNA (e.g., AZD8601), have demonstrated safety and biological activity in early-phase cardiac-repair trials125. Collectively, these examples show that delivery modality rather than RNA sequence alone governs biodistribution, dosing frequency, safety profile, and ultimately the clinical applicability of each RNA platform.

Synergistic approaches that combine RNA-based therapeutics with orthogonal modalities are rapidly maturing and provide practical routes to surmount biological barriers and improve outcomes. A leading clinical example is the combination of a personalized neoantigen mRNA vaccine with PD-1 blockade: the mRNA-4157 (V940) vaccine administered with pembrolizumab produced clinically meaningful improvements in recurrence-free and distant-metastasis-free survival in resected high-risk melanoma (KEYNOTE-942/mRNA-4157-P201), illustrating how RNA vaccines can be potentiated by immune-checkpoint inhibition to augment antitumour immunity126. In oncology and beyond, RNA agents are being deployed alongside small molecules that modulate target biology or the tissue microenvironment, for example, pairing RNA therapeutics that reduce pathogenic transcript abundance with small-molecule pathway inhibitors to create complementary on-target suppression and pathway blockade (for reviews of RNA-targeting small molecules and RNA small-molecule strategies, see recent reviews)127,128.

Gene editing modalities also provide synergistic opportunities: ex vivo CRISPR editing combined with RNA delivery (e.g., gRNA/mRNA delivery to engineered cells) enables durable cellular therapies (for instance, CRISPR-edited autologous HSC and CAR-T programs), and in vivo combinations of editing and transient RNA expression may allow correction plus temporary supportive protein expression129. Finally, advances in delivery chemistry, such as LNP optimization, biodegradable ionizable lipids and cell-targeting ligands, can be paired with immune-modulatory agents to reduce toxicity while enhancing uptake and endosomal escape, thereby improving the therapeutic index of combination regimens130,131. Together, these examples demonstrate that rationally designed combination strategies informed by mechanism, delivery and patient biology are a promising pathway to overcome delivery, immunogenicity and efficacy barriers for RNA therapeutics.132

Various delivery platforms for RNA therapy

The development of reliable carriers that can shield RNA molecules from harsh physiological conditions is critical, given their inherent instability, negative charge, and susceptibility to enzymatic degradation. Advances in nanotechnology and materials science have provided innovative solutions for overcoming these challenges by improving protection, circulation time, and cellular uptake. A flexible and efficient delivery platform can be achieved by tailoring both the physical properties of nanoparticles (such as size, shape, and chemical composition) and their biological characteristics (such as surface ligands for targeted delivery). Various RNA delivery systems have been developed using both viral and non-viral vectors, including LNPs, polymeric carriers, and dendrimers133,134. While viral vectors offer high transfection efficiency, they are costly, have limited packaging capacity, and raise biosafety concerns. In contrast, non-viral vectors are safer, more economical, and capable of accommodating a broader range of RNA cargos. The following section briefly discusses the major types of RNAi delivery platforms, their recent advancements, and the key challenges that must be addressed for successful clinical translation135.

Viral gene therapies

Viral gene therapies have demonstrated promising clinical outcomes, as evidenced by successful clinical trials136. The success of these methods can be limited by various factors, such as pre-existing immunity, virus-triggered immunogenicity, potential risks of unintended genomic integration, restrictions on payload size, difficulties with repeated dosing, challenges in large-scale production, and the high costs of vector manufacturing137,138. Despite ongoing efforts to address some of these limitations and enhance the safety and efficacy of viral gene therapies, these challenges have spurred the exploration of alternative drug delivery platforms139.

Researchers are actively seeking novel drug delivery vehicles that can overcome the drawbacks associated with viral vectors. These alternative delivery systems offer the potential to circumvent immune responses, minimize off-target effects, accommodate larger therapeutic payloads, facilitate repeated dosing regimens, simplify manufacturing processes, and reduce overall treatment costs140. By harnessing innovative technologies and engineering approaches, scientists aim to develop next-generation delivery platforms that can efficiently and safely deliver therapeutic genes to target cells and tissues, ultimately advancing the field of gene therapy and expanding its clinical utility141.

Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs)

LNPs are the most frequently utilized carriers for administering oligonucleotide medications, serving as comprehensive delivery systems. These LNPs comprise ionizable cationic lipids, cholesterol, phospholipids, and PEG-lipids. The core constituents, ionizable cationic lipids, form “lipoplexes” through electrostatic interaction with negatively charged nucleic acids, facilitating nucleic acid transfections in vitro, such as Lipofectamine™ RNAiMAX transfection reagents142. Helper lipids, phospholipids, and cholesterol are essential components that significantly improve the stability of formulations and enhance delivery effectiveness143. Furthermore, PEG-lipids regulate particle size, prevent aggregation, and prolong in vivo circulation durations, contributing to their versatility144.

The ionization behavior and surface charge of LNPs play a crucial role in mediating siRNA delivery, which is influenced by factors such as the acid dissociation constant (pKa). Positively charged LNPs coat anionic RNAs, facilitating their cell entry via receptor-mediated endocytosis and preventing nuclease degradation. Upon entering cells, LNPs undergo a decrease in pH, resulting in an increase in nanoparticle charge due to protonation and subsequent buffering capacity within endosomes. This buffering capacity contributes to endosome swelling and breaking, facilitating siRNA release into the cytosol, a critical step for its therapeutic action through RNA interference145. LNPs enable the delivery of various RNA entities, including mRNA and CRISPR–Cas components, to specific cells and tissues using advanced technologies like selective organ targeting (SORT), enabling tailored gene therapies for hepatic and rare diseases146. Moreover, optimizing LNPs’ pKa enhances RNA delivery efficiency, while branched-tail LNPs demonstrate the capability to co-deliver multiple mRNAs without inducing immunogenicity or toxicity147. Overall, LNP-based gene therapies are promising for treating hepatic diseases and other rare disorders, showcasing their potential for widespread application in RNA therapeutics.

LNPs represent a vital class of drug delivery systems, with FDA-approved variants demonstrating efficacy in liver siRNA delivery and mRNA vaccine administration148,149. The distinct structures of lipids within LNPs influence their interactions with cells, and researchers have extensively investigated lipid-based delivery systems to optimize the delivery of nucleic acids. Through various synthetic methods, scientists have developed diverse libraries of lipid delivery systems, with a particular focus on enhancing siRNA delivery to hepatocytes in mice. These efforts, coupled with a more targeted approach to lipid design, have significantly reduced the required dose for effective in vivo hepatocyte gene silencing in preclinical models150,151.

In summary, LNPs represent a versatile and promising platform for delivering RNA therapeutics. Key lipids, such as C12-200, cKK-E12, DLin-KC2-DMA, and DLin-MC3-DMA, have demonstrated efficacy in providing siRNA in non-human primates, with DLin-MC3-DMA notably utilized in the patisiran treatment for hATTR130. LNPs have also successfully delivered mRNA to the liver in various preclinical and clinical settings, showcasing their potential for widespread application. Recent advancements, including LNPs delivering base-editing Cas9 and sgRNA targeting PCSK9, have shown sustained gene silencing effects in non-human primates, with potential therapeutic benefits for cardiovascular diseases152. Figure 6 provides a detailed representation of LNP-mediated delivery of oligonucleotides and their intracellular fate.

Schematic illustration of oligonucleotide-loaded lipid nanoparticles showing cellular uptake via endocytosis, endosomal escape facilitated by ionizable lipids, and subsequent cytoplasmic release for RNA interference–based gene silencingc.

Polymers and polymer-based nanoparticles

Numerous RNA delivery methods that do not involve viruses also rely on polymers and polymeric nanoparticles. Chemists can modify polymer properties like charge, degradability, and molecular weight, which influence how effectively RNA is delivered into cells153. A commonly employed polymer is poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA). While the FDA has authorized PLGA drug delivery systems for administering small-molecule drugs, they have not yet approved them for nucleic acid delivery154. PLGA lacks the positive charge to bind to the negatively charged RNA phosphodiester backbone at a neutral pH. Therefore, scientists have modified PLGA by incorporating cationic chemical groups like chitosan to enable the delivery of siRNA in mice155.

PLGA lacks the positive charge necessary to form complexes with the negatively charged RNA phosphodiester backbone at a neutral pH. Researchers have introduced cationic chemical groups like chitosan to address this limitation and utilize PLGA for RNA delivery, enabling effective siRNA delivery in mice154. Polymers containing amine groups capable of becoming cationic, such as polyethylenimine (PEI) and poly(l-lysine) (PLL), can interact electrostatically with RNA, facilitating its cellular uptake156. However, unmodified PEI and PLL may not always be well tolerated, with PEI transfection efficiency and toxicity increasing with molecular weight157. Consequently, chemical modifications have been applied to enhance the in vivo performance and tolerability of PEI and PLL. For instance, nanoparticles incorporating PEG-grafted PEI have been employed to transport mRNA to immune cells in the lungs. At the same time, cyclodextrin-PEI conjugates have been utilized for in vivo mRNA vaccine delivery158.

Similarly, surface modification of iron oxide nanoparticles with PLL has enabled gene delivery to the central nervous system in mice159. Comparing poly(ethylene glycol) and poly(lactic lactate) to another class of cationic polymers, poly(beta-amino esters) (PBAEs), which are created by joining amine monomers to diacrylates, provides better biodegradation and less cytotoxicity160. These polymers were created to improve the delivery of RNA and DNA. They feature biodegradable ester linkages and cationic amines161. Initially, a variety of chemically different PBAEs were produced using Michael addition chemistry, and their effectiveness in delivering DNA and RNA in cell culture environments was evaluated162,163.

These PBAE ‘libraries’ facilitated investigations into how the chemical structure of PBAEs impacts drug delivery, leading to the establishment of design principles for subsequent PBAE development164. Initial guidelines suggested that effective polymers tended to be predominantly hydrophobic, containing mono-alcohol or di-alcohol side groups, and featuring linear bis(secondary) amines. A subsequent study employing these design criteria revealed that the most successful polymers predominantly comprised amino alcohols and exhibited chemical similarities, differing only by one carbon atom164. These studies demonstrated the viability of using high-throughput chemical synthesis and then high-throughput drug delivery evaluations; this approach has been applied to other chemical classes of nanoparticles, such as LNPs165. PBAEs have been utilized for delivering DNA vectors to pulmonary cells via nebulization, mRNA intranasally, and siRNA to a human orthotopic glioblastoma tumor model in mice166,167. More recently, PBAE-based polymers have been used by researchers to nebulize Cas13a mRNA and guide RNA into the respiratory tracts of mice and hamsters for the treatment of SARS-CoV-2168. Additionally, scientists have synthesized lipid-polymer hybrids, observing that the addition of lipids to PBAEs enhances serum stability and delivery efficiency169.

Inorganic nanoparticles

Non-viral inorganic NPs have grown into better miRNA and siRNA delivery techniques owing to their variable size, low cytotoxicity, imaging diagnostics, storage stability, targeting site, cross-biological barriers, and excellent pharmacokinetics. The inorganic NPs typically comprised metal nanoparticles (MNPs), magnetic NPs/Iron oxide NPs (IONs), mesoporous silica NPs (MSN), and calcium phosphate NPs etc170,171,172. Inorganic NPs provide an ideal scaffold for the development of RNA-based delivery vehicles for both in vitro and in vivo applications. They possess a high surface area to volume ratio, enabling optimal siRNA loading through either chemical conjugation or non-covalent encapsulation. A key benefit of these NPs has to do with their surface chemistry, which might be easily altered, allowing for the resolution of issues regarding in vitro and in vivo siRNA delivery. Additionally, the varied physical and optical characteristics of inorganic NPs can be exploited to track siRNA distribution to cells or tissues173. The negatively charged nucleic acids need to be bound and encapsulated by the cationic biomaterial transfection agent. Consequently, MNPs, which carry the positive charge, are the assigned cationic biomaterials for safe and effective intracellular delivery of RNA therapeutics174.

Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs)

The advanced surface chemistry of AuNPs, permitting the covalent or non-covalent siRNA conjugation, as well as their inert, non-toxic, and biocompatible core, is being explored strongly for siRNA delivery. Considering it, AuNPs are frequently researched along with hollow AuNPs or AuNP-siRNA conjugates as a captivating siRNA delivery system among various MNPs, owing to their optical properties173. As the most straightforward technique, thiol-gold covalent chemistry has been employed by Nagasaki and coworkers to deliver siRNA via siRNA-AuNP conjugates175. Multiple approaches, particularly amino acid-functionalized AuNPs (AA-AuNPs), mixed-monolayer-protected AuNPs (MM-AuNPs), and layer-by-layer-fabricated AuNPs (LbL-AuNPs), have established efficacy in nucleic acid delivery while preserving their safety and stability176. PEI-Au/human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) siRNA and PEI-Au/hTERTsiRNA@ ZGOC samples in B16F10 cells (a mouse melanoma cell line) displayed the anticancer impact177. In a rat model of type 1 diabetes, Pluronic F127 gels containing DsiRNA-AuNPs were found to have beneficial influences on diabetic wounds through fostering and improving angiogenesis and wound healing178. In a different manner, PEG-PEI polymer-coated AuNPs efficiently delivered siRNA to pancreatic stellate cells, silencing HSP47 and minimizing pancreatic cancer-associated desmoplasia179.

Mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSN)

MSN surfaces can be effectively coupled with siRNA thiolates for transport, and coating MSNs with cationic polymers has been found to be productive. A 10 KD PEI-coated MSNPs were discovered by Nel et al. to be capable of transporting siRNA and inhibiting the production of GFP in modified HEPA-1 liver cancer cells without causing cytotoxicity180.

Additionally, plenty of MNP-mediated RNA delivery systems, which target other genes, including Bcl2L12, c-Met, EGFR, PLK1, miRNA-21, VEGF, SSATB1, and Galectin-1, have been designed for glioma gene therapy approaches170. Hence, the curative value of inorganic NPs for the delivery of siRNA is being proven in a broad spectrum of disease conditions, suggesting a promising therapeutic future.

Metal-phenolic networks (MPNs)

To address a few insufficiencies in existing RNA delivery platforms, such as existing inflammation due to cationic components of NPs or restricted organ tropism, the polyphenol networks are stabilized by metal ions. In this way, the metal-phenolic networks (MPNs) are another ongoing, negatively charged metal-organic frameworks that evolved when polyphenols and metal ions coordinate under physiological settings. Because of its distinct architecture and chemical structure, MPNs possess several advantages, including ease of manufacture, excellent biocompatibility, acid sensitivity, and possible drug carrier changes for RNA delivery181.

In several kinds of cell lines, the modified mRNA-MPN nanoparticles exhibited improved transfection efficiency than conventional Lipofectamine. Similar to LNPs, they facilitate mRNA transport across multiple animal tissues, such as the liver, kidney, lung, heart, and spleen, as well as protein expression and gene editing in the brain. The noncationic nature, favorable biocompatibility, efficacy, and flexibility of mRNA-MPN NPs render them a suitable substitute for conventional mRNA delivery platforms172. In order to overcome issues with mRNA distribution by cationic nanoparticle elements, a study presented a noncationic nanoparticle platform. With the help of metal ions, the platform assembles mRNA into a network of poly(ethylene glycol) and polyphenol. Assessing a variety of components and respective compositional ratios yields a library with the ability to achieve stable, biocompatible, and robust mRNA transfection both in vitro and in vivo172.

Dendrimers

Dendrimers are a type of polymer utilized for RNA delivery, characterized by a specific number of branched monomers extending from a central core molecule. Amphiphilic dendrimer vectors share two important features with their chemical hydrophilic counterparts: RNA binding and RNA complex-stabilizing hydrophobicity. It promotes RNA encapsulation inside an established complex, resulting in an equilibrium that influences the efficacy of RNA delivery followed by endocytosis135. Dendrimers, an innovative form of cationic polymer, having a positive charge, enable electrostatic interactions with RNA molecules, stabilizing them and inhibiting enzyme degradation in systemic circulation182. Functionalised dendrimers facilitate the RNA uptake and minimize off-target effects while enhancing targeted distribution to cells or tissues. Cellular absorption and endosomal release have also been enhanced by their nanoscale size and tunable surface chemistry183.

Poly(amidoamine) (PAMAM)

The cationic functionality of dendrimers, such as poly(amidoamine) (PAMAM) or poly-L-lysine (PLL), is capable of forming complexes that enhance the delivery of RNA into cells. They have been shown to be critically important in delivering RNA to the CNS, serving as intramuscular vaccines, and transporting siRNA to hepatic endothelial cells184. The cellular internalization mechanism describes how dendrimers interact with RNA, resulting in cells taking up the biological and exogenous compounds. A study compared siRNA and PAMAM dendrimer complexes to siRNA and branched polyethylenimine (bPEI) complexes, finding that PAMAM-siRNA complexes showed better cellular uptake. Since dendrimers are internalized by an adsorptive endocytosis pathway, membrane adsorption and an adsorptive endocytosis mechanism are necessary for the effective uptake of PAMAM and PAMAM-siRNA complexes182. Bohr et al. investigated the potency of PAMAM dendrimers, which are extensively researched for nucleic acid delivery, in pulmonary distribution through generating dendriplexes with siRNA. These stable complexes confirmed the potent gene silencing as well as substantial cellular uptake in macrophages, signifying that they are capable of more efficient distribution of local RNA therapeutics182. Additionally, different kinds of cells readily internalize dendrimers and dendrimer-based nanoformulations via the ATP-powered clathrin-mediated endocytosis pathways. Modifications to dendrimer structure have been implemented to shield nucleic acids from enzymatic degradation and enhance their escape from endosomes185. PAMAM dendrimers could be chemically modified to enhance conventional dendrimers with minimized cytotoxicity. Recent research conducted by Joubert et al. showed enhanced mRNA condensation through gene transfection in vitro by effectively producing dendriplexes with mRNA186. The appealing features of dendrimers are now increasingly explored for potential carrier for mRNA-based vaccines, along with delivering drugs. Chahal et al. explored the use of a modified PAMAM dendrimer molecule to deliver mRNA replicons against Toxoplasma gondii, H1N1 influenza, and the Ebola virus187. Thus, dendrimers seem to have increased therapeutic value in a variety disease through modulating immunological and metabolic pathways as well as regulating gene expression via RNA delivery.

Cyclodextrins

Cyclodextrins (CDs), natural cyclic oligosaccharides, are being implemented as delivery vehicle for siRNA, igniting new interest in this area. CDs consist of modified starch derivatives composed of d-glucopyranose units linked by α-(1-4) interactions, which provides them with the appearance of a doughnut or stunted cone shape. Commercially available units of polysaccharides with low toxicity are α-, β-, and γ-CDs. Their distinct three-dimensional arrangement enables multiple compounds to create host-guest inclusion complexes. Among them, β-CD is the most widely utilized and extensively investigated compound, with several tests for toxicity that comply with FDA guidelines. The peculiar structure of β-CDenables different chemical inclusions too for efficient delivery of siRNA188,189.

CDs are excellent substitutes for the different cationic non-viral vectors utilized for siRNA delivery due to their 50–200 nm size range. Also, they act as adapter molecules, allowing substances like modified adamantanes to be merely “plugged” within the CD cone to provide extra functionality. By minimizing the utilization of modified siRNA, CDs shield siRNA from serum190. By functionalising CDs vectors with adamantane-transferrin (AD-Tf) and AD-PEG conjugates, siRNA is able to be administered to animals at therapeutic dosages suitable for humans. Research into CDP-based siRNA delivery systems for the treatment of various diseases is prompted by the fact that CDP-siRNA nanoplexes have an advantage over other siRNA-lipid complexes in that they do not trigger immune stimulation, while siRNA contains an immune stimulatory motif189,190. In order to target the essential cell death proteins Bim and PUMA, which become more abundant during sepsis, Brahmamdam et al. have developed a unique CD-based TfR-targeted delivery vehicle for siRNA treatment191. The CDs system effectively delivered siRNA to immune effector cells without creating detectable off-target effects, signifying a substantial improvement in the treatment of infectious and other disorders.

Albumin nanoparticles

Albumin, a soluble protein comprising 585 amino acid residues, sustains biological functioning across pH ranges 4–9. Its three-dimensional structure enables the distribution of drugs with various characteristics, whilst its amino and carboxyl groups serve as binding sites for polymers or ligands. Albumin nanoparticles (NPs) are a promising RNA delivery technology, notably for cancer therapy, since they are non-toxic, biodegradable, and extremely effective, which permits targeted distribution of RNA molecules to cells or tissues192. Energy-dependent albumin NPs permeate cells via clathrin- and caveolae-mediated endocytic pathways, ensuring the integrity of encapsulated nucleic acids and preventing their destruction. siRNA, a gene-silencing technique, relies on carriers such as albumin NPs for stability and efficacy. These nanoparticles promote siRNA internalization in tumor cells via transcytosis193.

Encapsulating the appropriate nucleic acids or RNA in albumin-based nanoparticles serves as one of the most common approaches to use albumins like bovine serum albumin (BSA) and human serum albumin (HSA) as a delivery system for RNAi in cancer therapy192,194. Numerous approaches, involving desolvation, thermal gelation, emulsification, nanospray drying, and self-assembly, may be employed to create these structures. The most often used technique among all of those is desolvation, which utilizes glutaraldehyde as a cross-linker and ethanol as a desolvating agent. As evidenced by the coating of HSA-LNPs-siRNA against GFP in breast cancer cells, albumin is utilized as a coating agent in lipid-based nanocarriers to improve delivery to target areas and minimize proximity to serum proteins195.

Cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs)

Amino acid sequences designated as CPPs have the ability to enter living cells and contribute to the uptake of a variety of payloads, including RNA, plasmids or even proteins. The CPP delivery vectors are designed to carry biologically relevant payloads, such as siRNA, to intracellular areas that are not typically internalized by cells196. The RNAi pathway is sometimes triggered by siRNA, a double-stranded RNA that might silence the production of a particular protein. However, siRNAs have a short half-life in the bloodstream and cannot pass through the plasma membrane. To address these issues, covalent conjugation, complex formation, and CPP-functionalized nanocomplexes are the techniques widely developed and applied to deliver siRNA over the plasma membrane using various CPPs197.