Introduction

The hazardous metal concentration of wastewater from industries is a serious concern as it can cause soil necrosis near streams and negatively impact animals living near disposal sites. Particularly in highly populated urban regions where wastewater is frequently utilized in agriculture, human exposure to polluted water is frequent. Considering the harmful effects of many industrial operations, including tanneries, pulp and paper mills, and batteries on aquatic ecosystems, mitigating pollution from metals is a global concern. Region-specific contamination rates differ, although heavy metal exposure is a global concern. According to reports, the main causes of heavy metal pollution in aquatic habitats are wastewater and industrial waste released into water bodies. The heavy metals adhere to particles, aggregate in rivers, and endanger the environment subsequently1.

Industrial discharges containing heavy metals, dyes, fertilizers, pesticides, and other chemical compounds introduce these contaminants into wastewater streams. The resulting soil contamination arises from two key factors: the stagnant, settled nature of wastewater itself, as well as the reuse of this contaminated wastewater for agricultural irrigation purposes2. Because of their greater density than water, metals are highly soluble in water and can attach themselves to the muscles and gills of fish. Because of their simple method of passing through the food chain, metal ions can be dangerous to living things. In humans, they can accumulate and cause serious health problems like cancer, renal failure, and cardiovascular illnesses3. The prevalence of heavy metals (HM) in the human body eventually results in toxicity, which in turn induces Minamata disease, Alzheimer’s disease, arrhythmia, muscular dystrophy, neurotrauma, multiple sclerosis, etc. Possibly immediate side effects such as vomiting, dehydration, sleepiness, nausea, renal failure, and stomach pain, or chronic side effects such as neurological disorders, physical abnormalities, muscular impacts, genetics, and hereditary difficulties can result from HM toxicity. The unrestrained exploitation of HMs to meet human needs has led to a critical level of contamination within the ecosystem. In living things, accumulation happens when certain metals are absorbed and stored at more rapid rates, followed by metabolization and excretion4.

Lead compounds, which comprise lead salts, oxides, and sulfides, includingdissolved lead, may be found in wastewater from industries. Lead can enter both aquatic and terrestrial environments when tainted wastewater is incorrectly dumped into rivers or sewage treatment plants. Lead may accumulate gradually in sediments, soils, plants, and animals, possibly leading to negative impacts on plant growth and contaminating water and other food sources5. In humans, even trace levels of lead in food or water can result in several health issues6, notably acute lead poisoning and persistent illnesses like cancer, diarrhea, nerve damage, paralysis, reduced cognitive function, and infertility. The permissible concentration of lead in agricultural soil is 85 ppm, but in wastewater, it is 0.01 ppm5.

Between 150,000 and 180,000 metric tonnes of nickel are released into the environment annually. Humans can be exposed to nickel compounds, including carbonyl, through inhaling aerosol particles, absorbing via the skin, or consuming tainted food or drink. Frequent exposure raises the amount of nickel in urine and increases the risk of allergies, skin infections, diarrhea, cancer, organ problems, and central nervous system malfunction. The acceptable limit of nickel in agricultural soil is 0.05 ppm, and in wastewater, it is 0.02 ppm7.

Nanobiotechnology employs a diverse array of methods that harness the capabilities of microorganisms and plants to synthesize beneficial nanocomposites composed of metals like calcium, titanium, gold, zinc, silver, yttrium, etc8. These metal oxide nanocomposites are expected to exhibit remarkable energy storage capabilities, therefore categorizing them as energy substances9. In medical, biomolecular detection, diagnostics10, medication administration, food production, agriculture, and waste management, among other fields, these nanocomposites are important11. Metallic nanocomposites have favorable optical, electrical, catalytic, magnetic, and biological properties, rendering them significant for applications in wastewater treatment, agriculture, tissue engineering, antibacterial, and antiviral approaches12. Yellow tartrazine (YT) dye is an environmental risk due to its harmful effects on fish and probable allergic reactions in people13. da Silva et al., 2019, reported that 48.7%, 50.2%, 35.3%, 40.7%, and 45.3% of imidazolium-based ions (C4MImPF6, C4MImCl, C4MMImNTf2, C4MMImCl, & C4MImNTf2) were deteriorated under UV light, while 43.6%, 45.4%, 32.7%, 36.8%, and 40.2% of the same compounds were damaged under visible light, respectively. The commercial titania P25 catalyst reduced 50.2% and 66.3% of C4MImCl under visible and ultraviolet radiation, respectively14. The heterogeneous photocatalysis of Ag/TiNPs achieved destruction of RhB (k = 0.0219 min− 1) under visible light irradiation after 120 min, demonstrating potential for reuse across 5 cycles with only a 5% decrease in photocatalytic efficiency15.

Nanomaterials are an exceptionally effective, selective, and stable option for the aqueous removal of hazardous metal contaminants16. Trace elements are typically found in living tissues, and their shortage results in metabolic and structural imbalances17. Recent years have seen a surge in interest in yttrium oxide (Y2O3) as an important rare earth compound. In terms of chemical catalysis and optronics device design, it serves as one of the foremost potential components. The recognized properties of Y2O3 include a high dielectric constant and exceptional thermal stability when in the powdered condition. Functional composite substances such as yttria-stabilized zirconia films and extremely effective additives can be made from Y2O3. Furthermore, it is investigated for possible photodynamic treatment and biological imaging uses. It is also commonly utilized as a binding substance for several rare-earth doping agents18.

Yttrium oxide exhibits antioxidant activity under physiological conditions and is of substantial interest. According to a recent study, Y2O3 nanocomposites prepared with a biological substance-based scaffold can stimulate angiogenesis and vascularization, which may have implications for tissue engineering. Due to its ability to generate hydroxyl free radicals, which may adsorb a wide variety of dyes, photolysis is a possible substitute. Y2O3 nanocomposites exhibit significant luminescence efficacy and are ideal substrates for rare earth metals19.

The non-biodegradability of heavy metals renders the remediation of contaminated water and soil particularly difficult20. Conventional remedies have drawbacks about biological processes when applied on a large scale21. A diverse array of materials, including surfactant-enhanced activated carbon, iron-based soil amendments, mining products, and industrial residue and wastes, have been utilized for adsorption9. The primary advantages of the adsorption process compared to traditional treatment methods include lower cost, enhanced efficacy, less chemical usage, and the regeneration of the adsorbent post-reaction22. Biological agents are extensively utilized for the manufacture of metallic nanoparticles, encompassing both unicellular and multicellular species. Several significant examples include plant extracts, bacteria, viruses, fungi, yeast, algae, etc23. Fungi appear to be the most effective in heavy metal remediation due to their tolerance to stress conditions, rapid growth rate, and low nutritional requirements. Fungi can remove heavy metals through various techniques, including adsorption, ion exchange, valence transformation, intracellular precipitation, and extracellular precipitation. The fungal cell wall consists of chitin, a linear chain of beta-1,4-linked N-acetylglucosamine, together with polymers, glucan, proteins, and surface functional groups like amino, carboxyl, hydroxyl, phosphoryl, and imidazole24.

The primary goal of this research is to explore the adsorption process for removing lead and nickel from industrial wastewater, followed by the degradation of these toxic metals using Y2O3 nanocomposites synthesized with the aid of the fungus Aspergillus penicillioides. The biologically produced Y2O3 nanocomposites were thoroughly characterized, and the batch adsorption approach was employed to investigate the parameters affecting the adsorption process of lead and nickel metals25. Simultaneously, Y2O3 nanocomposites’ photocatalytic activity26 was investigated employing crystal violet dye. A quantitative technique called Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy was utilized to ascertain the quantity of hazardous metal ions, specifically deteriorated lead and nickel, present in the samples. Additionally, the biological applications have been demonstrated, including analysis of bacterial protein leakage, antioxidant properties27, and antibiotic efficacy28. The hemolytic assay was used to assess the Y2O3 nanocomposite’s ecological compatibility. This extensive approach investigates the extent to which Aspergillus penicillioides arbitrated Y2O3 nanocomposites eliminate the lead and nickel ions from wastewater from industries, offering insightful information for applications including environmental remediation (Fig. 1).

Materials and methods

Fungal isolation

Approximately 75 samples of soil and water from different locations in Tamil Nadu, India, were collected sterilely. Water samples were kept in sterile, airtight containers, whereas soil samples were collected with a sterile scalpel and sealed in sterile, closed bags. The samples were then kept at the ideal temperature. Numerous soil and water samples were utilized as inoculums for the serial dilution procedure, and they were plated in a potato dextrose agar (PDA) medium with 20 µg/mL of lead nitrate and nickel sulfate. Following 3 days of incubation at 25–27 °C, the growth plates were examined under a microscope to record microscopic findings and determine colony morphology. Subculturing in the PDA medium containing lead nitrate and nickel sulfate allowed for the selection and subsequent purification of specific fungal colonies. Eventually, the concentration of lead nitrate and nickel sulphate was gradually increased up to 1000 µg/ml, and the pure culture was maintained in the PDA slants. The fungal isolate was identified based on its morphological and microscopic attributes (Lactophenol cotton blue (LPCB) staining), including color, mycelia consistency, spore formation patterns, etc. The fungal genomic DNA was extracted by utilizing the chloroform-isoamyl alcohol method (EXpure Microbial DNA Isolation Kit). The DNA was then amplified using the primers ITS1 (5′ TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGC 3′) and ITS4 (5′ TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC 3′). The resulting PCR products were purified with the Montage PCR Cleanup Kit (Millipore) and sequenced using the ABI PRISM® BigDyeTM Terminator Cycle Sequencing Kits in conjunction with AmpliTaq® DNA polymerase (FS enzyme) (Applied Biosystems).

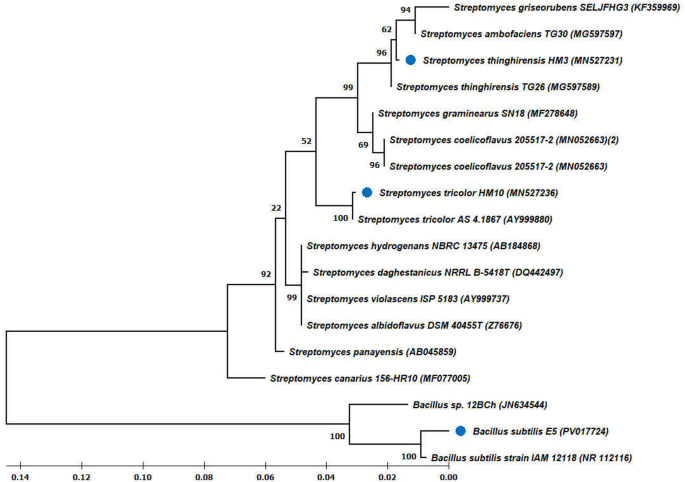

Moreover, single-pass sequencing was executed for every template employing universal primers for 18s rRNA. Through the process of ethanol precipitation, the fluorescently labeled fragments were isolated from the unregulated terminators. Following a resuspension in distilled water, the samples were electrophoresed using an ABI 3730xl sequencer (Applied Biosystems). The researchers employed the NCBI BLAST similarity search tool to conduct phylogenetic analysis, while the MUSCLE 3.7 software was utilized for generating multiple sequence alignments. Subsequently, the aligned sequences underwent refinement through the Gblocks 0.91b program, which eliminated aberrated regions and imperfectly aligned positions. After that, phylogenetic analysis was carried out utilizing the HKY85 substitution model and the PhyML 3.0 aLRT program. Using the Tree Dyn 198.3 program, an ensuing phylogenetic tree was generated.

Extracellular biosynthesis of Y2O3 nanocomposites

The plant-associated fungus (Aspergillus penicillioides) was introduced into 200 mL of potato dextrose broth, which included lead nitrate and nickel sulfate. For 96 h, at a temperature of between 25 and 27 °C, the resulting mixture was incubated in a rotary shaker that operated at 130 rpm. Following the incubation phase, the culture medium underwent filtering through Whatmann’s No. 1 filter paper, and the fungal mycelia were subsequently disintegrated in 150 mL of autoclaved double-distilled water and shaken at a speed of 130 rpm for 24 h at room temperature. After this incubation period, the resulting suspension was filtered again using Whatmann’s No. 1 filter paper, and yttrium oxide (Y2O3) nanocomposites were made from the filtrate. Using a rotating evaporator, the impurities were eliminated, and the resulting mixture was allowed to evaporate until it was completely dry. Gas Chromatography and Mass Spectroscopy (GC-MS) analysis (Perkin Elmer Clarus 680 & 600) was used to further identify the metabolic compounds present in the Aspergillus penicillioides extract. A 50 mL fungal metabolite filtrate was combined with a similar amount of 0.1 M aqueous yttrium nitrate hexahydrate (Y(NO3)3.6H2O) to produce the yttrium oxide nanocomposites29. For 2 h, the resulting mixture was heated to 60 °C on a hot plate using a magnetic stirrer. Following the formation of a white deposit, the precipitate was extracted, dried, and calcined to create a fine granule that was subsequently employed in additional characterization techniques.

Characterization studies on Y2O3 nanocomposites

Using an Agilent Technologies Cary 300 UV–visible spectrophotometer, the absorption of Aspergillus penicillioides arbitrated Y2O3 nanocomposites was measured in the 200–600 nm range. The nanocomposites underwent an examination of their optical characteristics through UV–visible spectrophotometer analysis. Additionally, the crystalline structure of the Y2O3 nanocomposites was identified by employing the X-ray diffraction (XRD) technique. The measurement was made on a Bruker D8 Advanced with a proportional counter and Cu Kα radiation (k = 1.5405 A, nickel filter) over a 2θ range of 10°–80° at a scanning rate of 5°/min. The Debye Scherrer equation, which can be expressed as follows (Eq. 1), is conceivably employed to determine the average crystalline grain size of the nanocomposite:

$${text{D}}=frac{{{text{K}}lambda }}{{beta {text{Cos}}theta }}$$

(1)

Here, λ indicates the wavelength (1.54), β the entire width at half maximum, and K the Scherrer constant (0.98). D indicates the diameter of the crystalline nanocomposites. The lattice microstrain (ε) is calculated from the Eq. (2)30,

$${text{Lattice}};{text{microstrain}}=frac{beta }{{{text{4Xtan}}theta }}$$

(2)

The Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) technique has been employed to determine the size distribution profile of synthesized nanocomposites in hydrodynamics. Zeta potential is the surface charge of the nanocomposites in a liquid solution. Zeta potential and DLS analysis may be performed with the Horbia Scientific SZ-100 equipment. It is an essential instrument that provides the condition of the surface of the nanocomposites and forecasts the colloidal dispersion’s long-term stability.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) measurements of surface morphologies were conducted with the support of a SEM model: Hitachi S-3400 with 45KX amplification and running at a voltage of 15.0 kV. Using the Energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) technique, the elemental composition of Y2O3 nanocomposites was examined. TEM, or transmission electron microscopy (FEI – TECNAI; Model: G2–20 TWIN, operating voltage 200 kV), is an additional effective method for characterizing nanomaterials. The size, shape, and distribution of the particles can be ascertained quantitatively. Similar to SEM, TEM is an electronic spectroscopic imaging method, but with a better resolution. With Bruker FM: MIR – FIR/THz Spectroscopy, the presence of functional groups in Y2O3 nanocomposites was evaluated in the 4000–400 cm− 1 range (FTIR analysis). The absorption bands and spectral peak positions provide information about the synthesized Y2O3 nanocomposite’s chemical bonding, structure, and shape.

Applications of the Y2O3 nanocomposites

Batch adsorption studies

The study evaluated the ability of the Y2O3 nanocomposite to adsorb lead and nickel (toxic metal ions) from simulated wastewater through a batch adsorption process driven by photocatalytic activity. The freshly generated wastewater containing lead nitrate and nickel sulfate (100 µg/mL) was mixed with 2 µL of Y2O3 nanocomposite (4 µg/mL) and swirled at room temperature at 150 rpm to evaluate the photocatalytic activity. Numerous procedures were optimized to obtain maximum adsorption, including pH (5–9), lead and nickel concentrations (2–100 µg/mL), Y2O3 nanocomposite concentrations (2–10 µg/mL), and the type of irradiation (UV and sunlight) for 5 h. Samples were removed from the adsorption study every 1 to 5 h on average. After everything was in balance, the catalyst was removed and centrifuged for 10 min at 8000 rpm to analyze it in a UV spectrometer. By using Eq. (3), the percentage of degradation was calculated.

$$%;{text{of}};{text{degradation=}}frac{{({text{Absorbance}};{text{of}};{text{control}}-{text{Absorbance}};{text{of}};{text{sample}})}}{{{text{Absorbance}};{text{of}};{text{control}}}} times 100$$

(3)

Adsorption kinetics and isotherm studies for lead and nickel elimination

Adsorption isotherm and kinetics studies were employed to examine the rate, mechanism, propensity, and functions of the Y2O3 nanocomposite towards toxic metal ions such as lead and nickel adsorption. To assess the scientific information acquired in batch adsorption investigation, the Langmuir and the Freundlich isotherms, pseudo-first-order, and pseudo-second-order kinetics were examined31. Equations (4), (5), (6), and (7) showed the appropriate equations for each of them.

$$frac{{{text{C}}_{{text{e}}} }}{{{text{q}}_{{text{e}}} }} = frac{{{text{C}}_{{text{e}}} }}{{{text{q}}_{{text{m}}} }} + frac{{text{1}}}{{{text{kq}}_{{text{m}}} }}$$

(4)

$${text{Log}};{{text{q}}_{text{e}}}=frac{1}{{text{n}}};{text{log}};{text{Ce}};{text{+log}};{text{k}}$$

(5)

$${text{Log }}left( {{text{qe}} – {text{qt}}} right)={text{log }}left( {{{text{q}}_{text{e}}}} right) – frac{{text{k}}}{{2.3}} times {text{t}}$$

(6)

$$frac{{text{t}}}{{{{text{q}}_{text{t}}}}}=frac{1}{{{text{kq}}{{text{e}}^{text{2}}}}}+frac{{text{t}}}{{{{text{q}}_{text{e}}}}}$$

(7)

AAS analysis of lead and nickel elimination

Lead and nickel were among the heavy metals that were identified using Perkin Elmer, AANALYST 400, atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS). The hollow cathode lamps that used air acetylene as fuel were the source of radiation for Pb and Ni. Standard absorbances for Pb and Ni are 217 and 232, respectively, using a 0.7 slit width. Triplicate analyses were conducted on both initial and final concentrations of lead and nickel in the wastewater (i.e. after the water is treated with Y2O3 nanocomposites). The blank and standards were thus atomized, and the outcomes were noted. Following the plotting of a calibration curve for each solution, the sample solutions were atomized and examined. Employing the calibration in combination with the absorbance measurements performed for the unknown samples, the different metal concentrations in the samples were determined.

Photocatalytic activity of Y2O3 nanocomposite: dye degradation

To investigate the photocatalytic activity of Aspergillus penicilliioides arbitrated Y2O3 nanocomposites, the degradation of crystal violet (CV) under UV light was employed. The UV light source (365 nm) for this study consisted of 4 × 10 W bulbs. The reaction was set up using 0.1 g of Y2O3 nanocomposites in a container holding 10 mL of crystal violet solution at 10 ppm. The decomposition of the crystal violet has been observed using UV-vis spectroscopy, and the results suggest that Y2O3 nanocomposites might adsorb the crystal violet dye. Additionally, various concentrations of Y2O3 nanocomposites (50 µg/mL and 100 µg/mL) and time intervals (2 and 4 h) were used to investigate the photocatalytic abilities of the Y2O3 nanocomposites (23 complete factorial design analysis)32.

Antibacterial study on Y2O3 nanocomposites

Agar-well diffusion method

The antibacterial characteristics of the synthesized Aspergillus penicillioides arbitrated Y2O3 nanocomposite have been evaluated using the agar well diffusion assay on the following bacterial strains: Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Bacillus subtilis, Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, and Proteus vulgaris33. Sterile swabs were used to swab the cultures of the strains specified above that were cultivated on Muller-Hinton agar plates. The agar plates were punctured and wells were filled with the Y2O3 nanocomposite at concentrations of 25, 50, 75, and 100 µg/mL. The plates were then incubated at 37 °C for 24 h hrs. The zone of inhibition values’ diameter indication was documented and examined with the positive control sample (ampicillin)34.

Bacterial growth kinetics

The bacterial isolates, including P. aeruginosa, E. coli, P. vulgaris, S. aureus, and B. subtilis, were cultured in LB broth and exposed to different concentrations of Aspergillus penicillioides arbitrated Y2O3 nanocomposites (50 and 100 µg/mL) to study their growth kinetics. The inoculated flasks were incubated at 37 °C in a rotary shaker for about 10 h to ensure proper agitation. The nanocomposites-treated bacterial cultures were used as samples, while untreated cultures served as controls. Optical density at 600 nm was measured hourly for up to 10 h, and these readings were plotted over time to evaluate the growth curves for the bacterial samples. The results allowed for the evaluation of Yttrium oxide nanocomposites’ effectiveness in inhibiting bacterial multiplication35.

Protein leakage analysis

The bacterial protein leakage assay was conducted using the Bradford assay. Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, including P. aeruginosa, E. coli, P. vulgaris, S. aureus, and B. subtilis, were inoculated in sterile LB broth. Various concentrations (50 and 100 µg/mL) of myco-synthesized Y2O3 nanocomposites were added to the cultured flasks. Then, the flasks were incubated at 37 °C for 8 h, with controls maintained. Samples were centrifuged every 2 h at 6000 rpm for 15 min. Then, 200µL of the supernatant and 800µL of Bradford reagent were mixed and kept undisturbed at room temperature in the dark for 10 min. The absorbance of the samples was measured at 595 nm. Bovine serum albumin (BSA) was used as the standard protein36.

Antioxidant activity: DPPH assay

The 2,2-diphenylpicrylhydrazyl (DPPH) assay is a prominent biochemistry test used to evaluate a biomolecule’s ability to scavenge free radicals. To perform the assay, a 0.1 mM DPPH solution and various concentrations of Y2O3 nanocomposites were prepared using methanol. 3 mL of the DPPH reagent was mixed with the different concentrations of Y2O3 nanocomposites (20–100 µg/mL), properly combined, and incubated at room temperature for 30 min in the dark. The sample’s absorbance was then measured at 517 nm. Ascorbic acid was used as the standard, and 3 mL of DPPH in methanol served as the control37. The following formula (Eq. (8)) was used to calculate the DPPH scavenging potential:

$$% {text{ DPPH}};{text{ radical }};{text{scavenging }};{text{assay}}=frac{{left( {{text{Absorbance }};{text{of}};{text{ control }}-{text{ Absorbance}};{text{ of}};{text{ sample}}} right)}}{{{text{Absorbance}};{text{of}};{text{control}}}}; times ;{text{1}}00$$

(8)

Hemolytic assay

A hemolytic analysis was carried out to assess the cytotoxic effects of the myco-synthesized yttrium oxide nanocomposites in a biological system. This assay evaluated the immediate toxicity of the Y2O3 nanocomposite sample at different concentrations on human red blood cells (RBCs). To conduct the assay, 1 mL of heparinized human blood was collected from a donor, and the RBCs were isolated by centrifugationat 1000 rpm for 5 min. After removing the supernatant, the RBCs were washed with PBS. 100µL of 1% RBC suspension was incubated with different concentrations of Y2O3 nanocomposites (20, 40, 60, 80, and 100 µg/mL) for 2 h at 37 °C. Following incubation, the samples were spun at 1000 rpm for 5 min, and the supernatant’s absorbance was evaluated at 545 nm to assess RBC lysis. Triton X-100-treated RBCs were employed as a positive control, PBS-treated RBCs were utilized as a negative control, and ampicillin was employed as the standard38. The hemolysis percentage was determined using the formula (Eq. (9)):

$$% ;{text{of}};{text{hemolysis}}=frac{{({text{Absorbance}};{text{ of}};{text{ sample}}-{text{Absorbance }};{text{of }};{text{negative }};{text{control}})}}{{left( {{text{Absorbance }};{text{of}};{text{ positive}};{text{ control }} – {text{ Absorbance}};{text{ of}};{text{ negative }};{text{control}}} right)}}; times ;{text{1}}00$$

(9)

Desorption and reutilization efficacy of Y2O3 nanocomposites

The adherence of lead and nickel to the surface of nanocomposites is a reversible process, allowing for the reutilization of nanocomposites following the desorption of metal ions. To extract metal ions from the nanocomposite surface, a 2.0 mL aliquot of a 1:1 combination of 0.1 mol/L NaOH and methanol exhibited optimal desorption efficiency. The adsorbent underwent many adsorption/desorption cycles to assess its reusability. Following each extraction, the adsorbent was employed in successive extractions after being eluted with the identical solution for the next cycle39. The adsorption-desorption experiment was conducted again, and Eq. (10) was utilized to calculate the adsorption efficiency.

$${text{Adsorption}};{text{efficiency }}left( % right)=frac{{{text{V}}left( {{{text{C}}_{text{o}}} – {{text{C}}_{text{e}}}} right)}}{{text{M}}}$$

(10)

In this context, Co and Ce signify the initial and optimal metal ion concentrations (mg/L), respectively, V indicates the solution volume (L), and M denotes the mass of the Y2O3 nanocomposites (g).

Statistical analysis

Each experiment was run through the process three times for each test, the standard deviation was computed, and the entire set of observations was subjected to one-way ANOVA, and p-value analysis was carried out by using Microsoft Excel and Minitab.

Results and discussions

Isolation and identification of fungal species by using 18s rRNA sequencing

The potato dextrose agar medium containing lead nitrate and nickel sulfate initially had white margins made of white mycelium, which swiftly turned black with conidial development (Fig. 2a). The reverse is white to cream in color. LPCB staining reveals septate and hyaline hyphae of the fungus. When conidial heads attain maturity, they begin to divide into loose columns and radiate in black color. Conidia have a brown color and sporadic ridges. Vesicles with an oval or flask shape are found in conidiophores (Fig. 2b). The isolated fungus’s genomic DNA was extracted via the chloroform-isoamyl alcohol method and subsequently amplified through PCR, utilizing the ITS1 forward and ITS4 reverse primers. In fungal species, the rRNA cistron region known as ITS1 is useful for metagenomic research. The ABI 3730xI sequencer was then used to acquire the ITS region sequencing, yielding 1210 base sequences. Additionally, the NCBI blast tool was used to blast the sequence, and MUSCLE 3.7 was used to perform the multiple sequence alignment. Additionally, phylogenetic analysis was performed using the program PhyML 3.0 aLRT, which determined that the isolated fungus was “Aspergillus penicillioides” (Fig. 3) and the gene sequence was documented in the NCBI gene sequence as ‘Aspergillus penicillioides VDRVYF’ with the accession number PQ570604.1 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/2847402264).

(a) The fungal colony initially appeared as white mycelium at the edges of the potato dextrose agar but rapidly turned black due to the production of conidia (asexual spores). (b) When stained with lactophenol cotton blue, the fungal hyphae (filaments) showed cross-walls (septa) and were transparent (hyaline). The conidial heads, which bear the conidia, were black and radiated outwards, tending to split into loose columns as they matured. The individual conidia were brown with irregular ridges, and the conidiophores (spore-bearing structures) had oval or flask-shaped vesicles. (c) The yttrium oxide nanocomposite material had a creamy white powder appearance.

A common food source of Aspergillus penicillioides is moisture-less foods such as grains, roasted nuts, fish, fruits, and herbs. In addition, it is commonly detected in shredded coconut, electronic meters, binocular glasses, and human skin. Various fungal isolates, including species from the genera Aspergillus, Trichoderma, Fusarium, Phanerochaete, Rhizopus, and Pythium, have demonstrated the potential to scavenge heavy metals. Among these isolates, Aspergillus penicillioides F12 (MN210327) manifested the ability to scavenge toxic metals such as lead (Pb) and cadmium (Cd) under optimal conditions of pH, temperature, and incubation time. The scavenging property of Aspergillus penicillioides F12 (MN210327) towards toxic metals like Pb, Cd, and Hg was found to be highest at optimal environmental conditions40.

Extracellular biosynthesis of Y2O3 nanocomposites

The bioactive molecules have been extracted and employed to produce Y2O3 nanocomposites using the extracellular synthesis process of Aspergillus penicillioides. GC-MS analysis was used to identify the metabolic components of Aspergillus penicillioides. The fungal extracellular extract chromatogram is displayed in Fig. 4. Eleven peaks were visible on the chromatogram, affirming the 2-to 30-min retention period. Utilizing the NIST library database, the metabolic compounds were identified41. The results of the mass spectrometry study, which confirm the presence of intermediate molecules and secondary metabolites, are shown in Table 1. The fungus extract yielded 20 compounds that were effectively determined. Potent production of Y2O3 nanocomposites results from the reaction of fungal bioactive compounds with yttrium nitrate hexahydrate (Y(NO3)3.6H2O), facilitated by an adequate stirring mechanism and regulation of temperature. Periodically monitoring the color change of the solution, it became creamy white, indicating the development of Y2O3 nanocomposites. The Y2O3 nanocomposites were white after the impurities were eliminated using the calcination process (600 °C for 3 h) (Fig. 2c). Bioactive molecules found in fungus extracts serve as capping, reducing, and stabilizing agents during nanocomposite formation.

Organisms employ extracellular strategies to prevent the uptake of toxic metals. One of the initial extracellular defenses against metal toxicity in fungi is the binding or biosorption of metals. Other mechanisms to avert metal entry into cells include the extracellular release of enzymes that inhibit toxicants or agents that chelate pollutants, as well as the suppression of transporters that facilitate the influx of toxicants. Filamentous fungi are intriguing organisms for bioremediation applications due to their capacity to transfer molecules, including toxic metals, within their mycelium or midst of their mycelium and plant symbionts. Additionally, the microtubule system and secretory vesicles facilitate long-distance transport, serving as pathways and carriers for this translocation process42.

The extracellular production of Y2O3 nanocomposites is fundamentally linked to the heavy metal resistance pathways utilized by filamentous fungi in stressful environments. In response to toxic metal ions like Pb2+ and Ni2+, fungi activate adaptive mechanisms, which include the secretion of diverse extracellular bioactive compounds, including NADH-dependent nitrate reductase, acid phosphatases, thiol-containing peptides, metal-binding proteins, and low-molecular-weight chelators, including organic acids and phenolic compounds. These metabolites function as the primary defensive mechanism, obstructing metal ingress into the cytoplasm by complexing or decreasing ions in the extracellular environment. The release of metal not only safeguards the fungal cells but also generates a bioactive extracellular matrix that can diminish metal precursors and stabilize freshly synthesized nanocomposites8.

Characterization of Y2O3 nanocomposites

The UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Fig. 5a) provides insights into the optical energy band gap exhibited by the generated Y2O3 nanocomposites. A prominent and abrupt peak at 284 nm (λmax) is observed in the generated Y2O3 nanocomposites. This clarifies the electron excitation caused by photons absorbed from UV light from its valence to the conduction band. The optical energy band gap (Eg) of 4.37 eV has been computed. The absorption spectra of Y2O3 (yttrium oxide) typically exhibit an exciton band in the wavelength range of 235 to 400 nm. This characteristic band arises due to the inherent energy gap (bandgap), the midst of the valence band and the conduction band in the material. The bandgap results from the transfer of electrons through the valence band to the higher-energy conduction band43.

The X-ray diffraction analysis of the generated Y2O3 nanocomposites is displayed in Fig. 5b, with diffraction peaks located at 2θ values of 11.993, 20.735, 29.384, 33.893, 36.009, 39.874, 43.739, 48.615, 53.308, and 57.725. The XRD spectra of the nanocomposite material display multiple well-defined, intense peaks, indicating the presence of crystalline regions within the nanocomposite structure. The intense peaks at 2θ values of 29.384, 33.893, 43.739, 53.308, and 57.725 with corresponding planes (222), (400), (431), (440), and (622) show the thickness and lattice size of the generated Y2O3 nanocomposites. With a crystallinity of 80.4% and a lattice strain size of 0.00358, the synthesized Y2O3 nanocomposite’s typical crystal diameter was found to be 31.4 nm through the use of the Debye-Scherrer equation. The size, lattice thickness, and crystalline structure of the generated Y2O3 nanocomposites increase their likelihood of binding to lead and nickel molecules and boost their catalytic potential.

The average particle diameter of the synthesized Y2O3 nanocomposites was 61.9 nm, as shown by the size distribution profile in Fig. 6a. By comparing XRD data with DLS data, it is confirmed that the generated nanocomposite ranges in size from 31.4 nm to 61.9 nm. As shown in Fig. 6b, the synthesized Y2O3 nanocomposites are thought to be a relatively stable colloidal dispersion, possessing adequate negative surface charge to hinder rapid aggregation, with a zeta potential of − 20.7 mV. Their anionic nature enhances colloidal stability and promotes electrostatic interactions with cationic heavy metal ions such as Pb2+ and Ni2+. SEM analysis reveals the morphology of the Y2O3 nanocomposites. Figure 7 displays a uniform spherical shape of the synthesized Y2O3 nanocomposites. Agglomeration is due to the high surface energy of the nanocomposites. According to the EDX spectrum analysis, Fig. 6 indicates the presence of C, O, and Y in atomic percentages of 57.75%, 33.10%, and 9.15%, respectively. Thus, the fabricated nanocomposites were highly pure, with the confirmation of the presence of yttrium. TEM analysis was used to execute a more thorough structural study. Figure 8 shows the entire surface of the Y2O3 nanocomposite at a lower magnification. An agglomeration of spherical particles characterized the morphology of the Y2O3 nanocomposite. Despite some of them being partially aggregated, the majority of the nanocomposites were organized well. TEM examination, on the other hand, shows almost uniformly sized sheet- and spherical-like particles. However, the TEM images also clearly show particle aggregation.

To assess the purity and composition of the Y2O3 nanocomposites, an FT-IR analysis was performed. The existence of any functional group or substance in the generated Y2O3 nanocomposites can be understood with the aid of the FT-IR spectra (Fig. 9). The broad absorption peaks at 3637 cm− 1, 3600 cm− 1, and 2348 cm− 1 are closely related to the hydrogen bond stretching vibration that occurs between the surrounding hydroxyl functional groups, the water molecules, and the presence of carbon on the surface. Additionally, the formation of peaks at 1078 cm− 1 and 679 cm− 1 indicates the C–O stretching and bending secondary alcohol group, whereas the broad and sharp peaks at 1365 cm− 1 and 770 cm− 1 are attributed to the C–H bending alkane and alkene group. The formation of sharp peaks at 1318 cm− 1 and 560 cm− 1 because to the linkage of S=O sulfone and Y-O stretching bond between the yttrium oxide and fungal bioactive molecules. Further, 1672 cm− 1 and 1681 cm− 1 attribute the C=O conjugated, C=C α, β-unsaturated ketone group 32,44. Moreover, the Y-O stretching peak at 560 cm− 1 specifies the yttria phase formation.

Applications of the Y2O3 nanocomposites

Batch adsorption studies

The effects of pH, the source of irradiation, the dosage of catalyst, the dosage concentration of lead and nickel (toxic metal ions), and the amount of time of stirring were studied for 1 to 5 h using Y2O3 nanocomposite to serve as the catalyst. The findings from the batch adsorption investigations suggest that the ideal conditions for lead removal are 60 µg/ml of lead and 4 µg/ml of Y2O3 nanocomposite in a reaction solution that is agitated for 5 h (Fig. 10). In Fig. 11, it is indicated that the pH of the solution is altered to 6 when exposed to a UV light source. A reaction mixture containing 60 µg/ml of nickel and 2 µg/ml of Y2O3 nanocomposite, with a pH of 6 and an irradiation source of UV light, was utilized to eliminate nickel. The degrading process for lead and nickel emerged after a comparison between the obtained parameters and the results.

Lead and nickel removal is reduced when both the amount of toxic metals and time increase. At a lead concentration of 60 µg/ml, the mixture must be agitated for 5 h to remove 60% of the lead at the maximum level. At lower concentrations, lead molecules bind to the active site of the Y2O3 nanocomposite. Since more active sites in the Y2O3 nanocomposite are occupied, lead reduction is hence reduced. Similarly, 70% of the nickel was adsorbed in 5 h at the maximum level of 60 µg/ml of nickel content.

Increasing the dosage of the adsorbent causes the toxic metals (lead and nickel) to be removed, and the removal level rises with time. Y2O3 nanocomposite concentration increases cause an increase in the amount of hazardous metal ions (lead and nickel) decomposition because more active sites are available for lead and nickel ions to adsorb. With an increase in the contact period between the hazardous metal ions and the nanocomposite, more lead and nickel ions promote up on the open sites of the Y2O3 nanocomposites. 70% of the lead and 75% of nickel may be efficiently removed in 5 h at a pH of 6, which is the lowest. When the pH of the mixture is 5, 7, 8, or 9, the removal percentage of toxic metal ions is lower. The lead and nickel ions adsorption and protonation of the Y2O3 nanocomposite were carried out at pH 6. The method of eliminating lead and nickel ions using a Y2O3 nanocomposite as a catalyst was conducted under UV light and sunlight as an irradiation source, with sunlight achieving maximum degradation of 23% of lead and 30% of nickel.

Adsorption isotherm and kinetics investigation

The validity of the data gathered from batch adsorption research was confirmed through analysis of the reaction mixture, which included the lead and nickel elimination product, for the adsorption isotherm and kinetic models. The Langmuir isotherm was expressed as Ce versus Ce/qe, compared to the log Ce versus log qe used in the Freundlich isotherm model31 as shown in Figs. 12a and 13a. Using the plots of pseudo-first-order (t vs. log (qe − qt)) and pseudo-second-order (t vs. t/qt) kinetics variables31 for the lead and nickel adsorption results, were determined as well in Figs. 12b and 13b. Since hazardous metal ions’ adsorption on their surface was proven to fit both the pseudo-first-order kinetic and the Freundlich adsorption isotherm, the R2 values demonstrated the effectiveness of Y2O3 nanocomposites in the elimination of lead and nickel. The Freundlich adsorption isotherm validated multilayer adsorption on a heterogeneous surface with changing adsorption energies, whereas the constant parameter in the reaction was identified as pH by pseudo-first-order kinetics.

(a) Adsorption isotherm model for the adsorption of lead by Y2O3 nanocomposite (b) Adsorption kinetic model for the adsorption of lead by Y2O3 nanocomposite.

(a) Adsorption isotherm model for the adsorption of nickel by Y2O3 nanocomposite (b) Adsorption kinetic model for the adsorption of nickel by Y2O3 nanocomposite.

AAS analysis of lead and nickel elimination

The lead and nickel blank and standard samples begin by being used to calibrate the instrument. Atomic absorption spectroscopy was used to assess the lead and nickel (toxic metal ions) initial and final concentrations (treated with Y2O3 nanocomposites) in the wastewater. The final concentration of lead (1.172 mg/mL) and nickel (1.172 mg/mL) was found to be less than the initial level of concentration of toxic metal ions (lead (0.80 mg/mL) & nickel (0.736 mg/mL)) (Table 2) and it indicates the adsorption percentage of lead and nickel is 31.74 and 37.2. Consequently, the produced Y2O3 nanocomposites serve as an efficient bioremediating agent and are suitable for the treatment of wastewater from industries.

Dye degradation: factorial design statistical analysis

As shown in Table 3, many factors, including pH, concentration, and time, were investigated at both the lowest (pH is 2; concentration is 50 µg/mL, and time is 2 h) and highest values (pH is 8; concentration is 100 µg/mL, and time is 4 h). The percentage of dye degradation was examined in the eight trials for each of the three parameters shown in Table 4. Using + 1 and − 1 for high and low levels, accordingly, an array was developed based on the analysis of 23 complete factorial designs with 8 tests for the elimination of crystal violet. The encoded values of the parameters and the outcomes (% elimination efficiency). More than 94% of dye degradation was observed in the pH of 4 & 8, Concentrations of 50 & 100 µg/mL, and a time of 4 h. The results confirm that time plays a key role in the dye degradation. The associations among the independent variables were evaluated by employing ANOVA (Analysis of Variance), and the fundamental impacts of crystal violet dye adsorption were selected following the results that were greater than a 95% confidence level45.

The coded equation: Y = predicted response (% removal efficiency), X0 = global mean, X1–X3 = regression coefficients corresponding to impacts of primary parameters (time, pH, and Y2O3 concentration in the initial solution), and X4 = interaction terms, delineated the 23 factorial analysis of crystal violet elimination by Y2O3 nanocomposites.

({mathbf{Y}},=,{{mathbf{X}}_{mathbf{0}}},+,{{mathbf{X}}_{mathbf{1}}}{mathbf{A}},+,{{mathbf{X}}_{mathbf{2}}}{mathbf{B}}+{{mathbf{X}}_{mathbf{3}}}{mathbf{C}}+{{mathbf{X}}_{mathbf{4}}}{mathbf{AB}}+{{mathbf{X}}_{mathbf{5}}}{mathbf{AC}}+{{mathbf{X}}_{mathbf{6}}}{mathbf{BC}}+{{mathbf{X}}_{mathbf{7}}}{mathbf{ABC}})

(% ;{text{of}};{text{ dye}};{text{ degradation}},=,{text{12}}.{text{17}}-{text{1}}0.{text{97 pH}},+,{text{8}}.{text{93 time}},+,0.{text{1215 Concentration}},+,{text{3}}.{text{825 pH}}*{text{Time}})

Aspergillus penicillioides arbitrated Y2O3 nanocomposites were utilized for photocatalytic degradation46, which yielded encouraging outcomes for a variety of parameters impacting the elimination of crystal violet dye. The association plot for the percentage of dye degradation (Fig. 14a) suggested that pH and time played a significant role, although the influence of pH versus concentration and time versus concentration on dye degradation was less apparent. The cube plot (Fig. 14b) shows the relationship between pH, time, and the concentration of the nanocomposite for the degradation. The main effect (Fig. 15a) shows that time had a greater impact on the elimination of dye, whereas the normal plot (Fig. 15b) underscored that pH and time had a greater impact on the elimination of crystal violet dye compared to concentration. Based on the results, the residual plot demonstrated that the linear model was suitable (Fig. 15c). In consonance with the Pareto chart (Fig. 14c), time and nanocomposite concentration had a greater impact on dye degradation than other variables. The counterplot (Fig. 16a) and surface plot (Fig. 16b) demonstrated that pH and time were critical factors in the elimination of crystal violet, and the equation supported the statistical relevance of dosage, time, and pH. The findings indicate that pH and time are crucial factors in the disintegration of crystal violet employing Aspergillus penicillioides arbitrated Y2O3 nanocomposites32.

(a) Interaction plots for % of dye degradation (b) Cube plots for % of dye degradation (c) Pareto Charts showing the effect of pH, time, and concentration on the % of dye degradation.

(a) The main plots for % of dye degradation (b) Normal plots of the standardized effect on % of dye degradation (c) The Residual plots for % of dye degradation.

Antibacterial study on Y2O3 nanocomposites

Agar well diffusion method

The antibacterial efficacy of the Aspergillus penicillioides arbitrated Y2O3 nanocomposites was evaluated against the following bacteria: P. aeruginosa, E. coli, B. subtilis, P. vulgaris, and S. aureus. The zone of inhibition obtained by employing nanocomposites is compared with the positive control (ampicillin). Y2O3 nanocomposites have strong antibacterial activity against B. subtilis, E. coli, and P. aeruginosa, where medium activity against P. vulgaris and S. aureus (Fig. 17). An electromagnetic reaction occurs on the nanocomposite surface due to the negative charge of the bacteria and the metal oxide nanocomposites, resulting in repulsive forces. This reaction leads to the generation of reactive oxygen species or the disruption of cellular components in the microorganism, resulting in cell death. Nanocomposites can interact with phosphorus- or sulfur-containing substances, such as DNA and protein thiol groups, inhibiting DNA replication and inactivating proteins may lead to damage to the bacterial cells. Moreover, nanocomposites can generate channels in bacterial cell walls, increasing cell permeability and ultimately causing cell death. Recent reports suggest that a long-lasting repulsive force between the bacterial cell walls and metal nanocomposites contributes to cell death. Due to their properties, Y2O3 nanocomposites can effectively function as antibacterial agents against microbes47.

Antibacterial activity—agar well diffusion method by using myco-synthesized Y2O3 nanocomposite against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria.

Bacterial growth kinetics

Bacterial isolates, including P. aeruginosa, E. coli, P. vulgaris, B. subtilis, and S. aureus, when cultured under standard conditions, typically go through the lag, log, stationary, and decline growth phases. However, when treated with Aspergillus penicillioides arbitrated yttrium oxide nanocomposites, the log phase of these bacteria was notably shortened, indicating the bacteriostatic and bactericidal properties of the myco-synthesized Y2O3 nanocomposites. Distinct lag phases were observed between the test cultures treated with Y2O3 nanocomposites and the untreated control cultures. While there was no significant difference in the overall growth rates of the test and control samples for the first 7 h, a slight decrease in growth was noted in the Y2O3 nanocomposite-treated bacteria afterward. This suggests that the nanocomposites penetrated the bacterial cells, initiating antibiotic action.

Yttrium oxide nanocomposites exhibit potent antibacterial properties against all five strains (Fig. 18). These nanocomposites interact with bacterial DNA, inactivate bacterial enzymes, and create perforations in cell membranes, leading to cell death. The effectiveness of these antibacterial agents is influenced by factors such as interaction charge, concentration, shape, size, and cell type. Research has conclusively shown that nanocomposites can easily infiltrate bacterial cells, thereby inhibiting or reducing bacterial growth48.

The growth curve of bacterial species treated with different concentrations of myco-synthesized Y2O3 nanocomposite (50 and 100 µg/ml) is depicted in the graphs.

Protein leakage analysis

The solution concentration, pH, treatment duration, active oxygen formation, surface properties, particle size, and shape are several factors that have been examined to determine the antibacterial effectiveness of metallic oxide nanocomposites49. Figure 19 illustrates the total protein produced in the samples by the treated cells, as determined by the Bradford assay. The protein release from the bacterial cells elevated with the concentration and duration of Y2O3 nanocomposites. Notably, the size of the nanocomposites significantly impacts their antibacterial efficiency. The outer membranes of bacterial cells contain pores of nanometer dimensions, suggesting that nanocomposites can easily penetrate these membranes due to their smaller diameters than the bacterial pores8. Additionally, the antibacterial activity of metallic oxide nanocomposites is primarily attributed to their surface interaction with protein thiol (-SH) groups in the cell walls. This synergism reduces cell porosity and leads to cell lysis. When the cell membrane is compromised, proteins, minerals, and genetic materials quickly leak out, resulting in cell death50.

Bacterial strains exhibited protein leakage, suggesting that many cells exposed to nanocomposites were compromised, with intracellular materials seeping into the surrounding solution (Fig. 19). The extent of cell membrane rupture, indicated by the increased production of the enzyme lactate dehydrogenase, is dependent on the duration of exposure36. The research shows that the antibacterial impact of myco-synthesized Y2O3 nanocomposites was particularly detrimental to P. aeruginosa, E. coli, B. subtilis, and P. vulgaris. In contrast, S. aureus showed a moderate protein leakage effect when treated with varying quantities of Aspergillus penicillioides arbitrated Y2O3 nanocomposites.

Antioxidant activity: DPPH assay

The 2,2-diphenylpicrylhydrazyl radical, a stable free radical, can be used to measure antioxidant activity51. The antioxidant potential of the Aspergillus penicillioides arbitrated Y2O3 nanocomposite was assessed by determining the inhibition levels of DPPH radicals and comparing them to ascorbic acid (used as a standard). The Y2O3 nanocomposite’s capacity to absorb DPPH radicals increased with its concentration. Figure 20 depicts the free radical scavenging activity of DPPH. The Y2O3 nanocomposite expressed antioxidant activity levels comparable to standard ascorbic acid. The results confirmed the effectiveness of the Y2O3 nanocomposite, derived from fungal metabolites, as a radical scavenger. Radicals serve as regulatory and signaling molecules in live cells and are naturally produced during cellular metabolic processes. Using ascorbic acid as a benchmark, the anti-oxidant IC50 value of the myco-synthesized Y2O3 nanocomposite was found to be 10.37 ± 0.04 µg, while the IC50 value for ascorbic acid was determined to be 27.29 ± 0.07 µg.

The myco-synthesized Y2O3 nanocomposite’s DPPH antioxidant inhibitory activity is depicted in the graph. The synthesized Y2O3 nanocomposite reveals a comparable level of antioxidant activity to standard ascorbic acid. The IC50 value was also computed using standard error, with a p-value of less than 0.05.

Hemolytic assay

The acute toxicity of the nanocomposites on red blood cells was determined by a hemolytic assay38. The percentage of Y2O3 nanocomposite samples that showed hemolysis ranged from 2.8 to 2.77%, with none of the doses showing any noticeable signs. Figure 21 shows that the Y2O3 nanocomposite performs well within acceptable ranges when compared to the standard ampicillin hemolysis percentage (2.78% to 2.82%). This finding concluded that the Y2O3 nanocomposite produced via mycosynthesis was non-hemolytic.

Desorption and reutilization efficiency of Y2O3 nanocomposite

The process of lead and nickel adsorption on the surface of a nanocomposite is reversible. After the desorption of hazardous metal ions, the nanocomposites can be reused. To extract the metal ions from the surface of the nanocomposites, 2.0 mL of a 1:1 solution of methanol and NaOH (0.1 mol/L) was employed to elute the adsorbent39. A multitude of cycles were conducted to evaluate the adsorbent’s reusability capacity. It was shown that after 7 cycles of adsorption and desorption, the regenerated adsorbent could eliminate over 93.4% of the targeted metal ions from the sample solution. The first cycle will eliminate 93.4% and the last 7th cycle will eliminate the metal ions up to 56.8% (Fig. 22).

A bar graph illustrating the reuse study of Y2O3 nanocomposites, along with their corresponding adsorption percentages for each cycle.

Future implications of the study

This study establishes a robust basis for the synthesis of Y2O3 nanocompositesutilizing Aspergillus penicillioides as a biological catalyst for the remediation of lead and nickel. This bio-mediated technique has significant promise for scaling to pilot and industrial applications, especially in the treatment of effluents from the electroplating, battery, and paint industries. To enhance the validation of the environmental compatibility and therapeutic safety of the nanocomposite, in vivo evaluations utilizing model organisms such as zebrafish, Drosophila melanogaster, or rodents can yield profound insights into biological distribution, metabolic pathways, and chronic toxicity.

Integrating real-time wastewater samples with intricate matrices will further assess the nanocomposite’s efficacy under diverse physicochemical conditions. Furthermore, integrating this technology with membrane filtration or bioreactor-based remediation units could improve practical use. Additional genetic and metabolic analysis of the fungal system may facilitate improved yield and customized nanostructures with heightened metal affinity. This bio-nanotechnological platform facilitates the development of advanced, sustainable solutions for heavy metal remediation that adhere to ecological and biomedical safety regulations.

Conclusion

Y2O3 nanocomposites are gaining significance in wastewater remediation (lead and nickel) due to their distinctive characteristics, including adsorption capacity, photocatalytic activity, chemical stability, selective binding, biocompatibility, and versatility while minimizing the use of chemicals and energy-intensive processes. The present research determined its adsorption capability by integrating and characterizing Y2O3 nanocomposites and using an appropriate batch adsorption analysis that considers the impacts of toxic metal ion concentration, pH, dose of the nanocomposite, and irradiation source. Major focus areas for this research include the kinetic studies and the adsorption isotherm. The most significant degradation of crystal violet dye using photocatalysis is 84% in 4 h and 23% in 2 h. The proportion of lead and nickel that remained in the wastewater was further confirmed by the AAS data and the adsorption percentage was found to be 31.74 and 37.2. Additionally, Y2O3 nanocomposites exhibited exceptional antibacterial and antioxidant activity. The hemolytic assay revealed the biocompatability of the Y2O3 nanocomposite. This study shows that wastewater may be efficiently treated to remove lead, nickel, and crystal violet using catalytic Y2O3 nanocomposites.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to confidentiality, but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request (NCBI gene sequence: [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/2847402264](https:/www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/2847402264) ).

References

-

Saravanan, A., Kumar, P., Duc, P. & Rangasamy, G. Strategies for microbial bioremediation of environmental pollutants from industrial wastewater: A sustainable approach. Chemosphere 313, 137323 (2023).

-

Muraro, P. C. L. et al. Ecotoxicity and in vitro safety profile of the eco-friendly silver and titanium dioxide nanoparticles. Process. Saf. Environ. Prot. 188, 584–594 (2024).

-

Sandrin, T. R. & Maier, R. M. Impact of metals on the biodegradation of organic pollutants. Environ. Health Perspect. 111, 1093–1101 (2003).

-

Engwa, G., Ferdinand, P., Nwalo, F. & Unachukwu, M. Mechanism and health effects of heavy metal toxicity in humans. In Poisoning in the Modern World: New Tricks for an Old Dog?, Vol. 10, 70–90 (2019).

-

Latif Wani, A., Ara, A. & Ahmad Usmani, J. Lead toxicity: A review. Interdiscip. Toxicol. 8, 55–64 (2015).

-

Samuel, M. S., Shang, M., Klimchuk, S. & Niu, J. Novel regenerative hybrid composite adsorbent with improved removal capacity for lead ions in water. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 60, 5124–5132 (2021).

-

Kumar, A. et al. Remediation of nickel ion from wastewater by applying various techniques: A review. Acta Chem. Malays. 3, 1–15 (2019).

-

Yamini, V. & Devi Rajeswari, V. Effective bio-mediated nanoparticles for bioremediation of toxic metal ions from Wastewater—a review. J. Environ. Nanotechnol. 12, 12–33 (2023).

-

Karuppusamy, I. et al. Ultrasound-assisted synthesis of mixed calcium magnesium oxide (CaMgO2) nanoflakes for photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 584, 770–778 (2021).

-

El-Naggar, N. E. A., El-Shall, H., Elyamny, S., Hamouda, R. A. & Eltarahony, M. Novel algae-mediated biosynthesis approach of Chitosan nanoparticles using Ulva fasciata extract, process optimization, characterization and their flocculation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 282, 136925 (2024).

-

Medina-Pérez, G. et al. Remediating polluted soils using nanotechnologies: Environmental benefits and risks. Pjoes com. 28, 1013–1030 (2019).

-

Soltau, M. et al. Copper nanoparticles from acid ascorbic: Biosynthesis, characterization, in vitro safety profile and antimicrobial activity. Mater. Chem. Phys. 307, 128110 (2023).

-

de Bôlla, L. et al. Calcium oxide nanoparticles: Biosynthesis, characterization and photocatalytic activity for application in yellow tartrazine dye removal. J. Photochem. Photobiol Chem. 447, 115182 (2024).

-

da Silva, W. L. et al. Petrochemical residue-derived silica-supported titania-magnesium catalysts for the photocatalytic degradation of imidazolium ionic liquids in water. Sep. Purif. Technol. 218, 191–199 (2019).

-

Muraro, P. C. L. et al. Ag/TiNPS nanocatalyst: Biosynthesis, characterization and photocatalytic activity. J. Photochem. Photobiol Chem. 439, 114598 (2023).

-

Samuel, M. S., Selvarajan, E., Chidambaram, R., Patel, H. & Brindhadevi, K. Clean approach for chromium removal in aqueous environments and role of nanomaterials in bioremediation: Present research and future perspective. Chemosphere 284, 131368 (2021).

-

Samuel, M. S. et al. Nanomaterials as adsorbents for as (III) and as (V) removal from water: A review. J. Hazard. Mater. 424, 127572 (2022).

-

García-Torra, V. et al. State of the Art on toxicological mechanisms of metal and metal oxide nanoparticles and strategies to reducetoxicological risks. Toxics 9, 195 (2021).

-

Yadav, T., Yadav, R. & Singh, D. Mechanical milling: A top down approach for the synthesis of nanomaterials and nanocomposites. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2, 22–48 (2012).

-

Samuel, M. S., Shah, S. S., Bhattacharya, J., Subramaniam, K. & Pradeep Singh, N. D. Adsorption of Pb (II) from aqueous solution using a magnetic chitosan/graphene oxide composite and its toxicity studies. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 115, 1142–1150 (2018).

-

Samuel, M.S., EA Abigail, M. & Ramalingam, C.. Biosorption of Cr(VI) by ceratocystis paradoxa MSR2 using isotherm modelling, kinetic study and optimization of batch parameters using response surface. PloS One 10 (2015).

-

Samuel, M. S. et al. Efficient removal of chromium (VI) from aqueous solution using Chitosan grafted graphene oxide (CS-GO) nanocomposite. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 121, 285–292 (2019).

-

Samuel, M. S. et al. A review on green synthesis of nanoparticles and their diverse biomedical and environmental applications. Catalysts 12, 459 (2022).

-

Samuel, S., Abigail, M., Chidambaram, R. & M, E. A. & Isotherm modelling, kinetic study and optimization of batch parameters using response surface methodology for effective removal of cr (VI) using fungal biomass. PLoS One. 10, e0116884 (2015).

-

El-Gamal, E. H., Rashad, M., Saleh, M. E., Zaki, S. & Eltarahony, M. Potential bioremediation of lead and phenol by sunflower seed husk and rice straw-based biochar hybridized with bacterial consortium: A kinetic study. Sci. Rep. 13, 21901 (2023).

-

Elnabi, M. K. A., Ghazy, M. A., Ali, S. S., Eltarahony, M. & Nassrallah, A. Efficient biodegradation and detoxification of reactive black 5 using a newly constructed bacterial consortium. Microb. Cell. Factories. 24, 154 (2025).

-

Almahdy, A. G., El-Sayed, A. & Eltarahony, M. A novel functionalized cuti hybrid nanocomposites: Facile one-pot mycosynthesis, characterization, antimicrobial, antibiofilm, antifouling and wastewater disinfection. Microb. Cell. Fact. 23, 148 (2024).

-

Eltarahony, M. M., Elblbesy, M. A., Hanafy, T. A. & Kandil, B. A. Synthesis, characterizations and disinfection potency of gelatin based gum Arabic antagonistic films. Sci. Rep. 15, 8279 (2025).

-

Govindasamy, R. et al. Sustainable green synthesis of yttrium oxide (Y2O3) nanoparticles using lantana camara leaf extracts: Physicochemical characterization, photocatalytic. Nanomaterials 12, 2393 (2022).

-

Mittemeijer, E. J. & Welzel, U. The ‘state of the art’ of the diffraction analysis of crystallite size and lattice strain. Z. Krist. 223, 552–560 (2008).

-

Bharathi, D. et al. Benzopyrene elimination from the environment using graphitic carbon nitride-SnS nanocomposites. Chemosphere 352, 141352 (2024).

-

Yamini, V. & Devi Rajeswari, V. Mycosynthesis of TiO2 nanoparticles using Aspergillus penicillioides for toxic metal removal and photocatalytic applications. J. Water Process. Eng. 106279 (2024).

-

Moro Druzian, D. et al. Cerium oxide nanoparticles: Biosynthesis, characterization, antimicrobial, ecotoxicity and photocatalytic activity. J. Photochem. Photobiol Chem. 442, 114773 (2023).

-

Urnukhsaikhan, E., Bold, B., Gunbileg, A., Sukhbaatar, N. & Mishig-Ochir, A. Antibacterial activity and characteristics of silver nanoparticles biosynthesized from carduus Crispus. Sci. Rep. 11, 21047 (2021).

-

Menon, S., Shrudhi, S. D., Agarwal, H. & Shanmugam, V. K. Efficacy of biogenic selenium nanoparticles from an extract of ginger towards evaluation on anti-microbial and anti-oxidant activities. Colloids Interface Sci. Commun. 29, 1–8 (2019).

-

Gunalan, S., Sivaraj, R. & Rajendran, V. Green synthesized ZnO nanoparticles against bacterial and fungal pathogens. Prog Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 22, 693–700 (2012).

-

Elbarbry, F. A. et al. Determination of antioxidants by DPPH radical scavenging activity and quantitative phytochemical analysis of ficus religiosa. Molecules 27, 1326 (2022).

-

Meiyazhagan, G. et al. Bioactivity studies of β-lactam derived polycyclic fused pyrroli-dine/pyrrolizidine derivatives in dentistry: In vitro, in vivo and in silico studies. PLoS One 10, (2015).

-

Jethave, G. et al. Exploration of the adsorption capability by doping Pb@ ZnFe2O4 nanocomposites (NCs) for decontamination of dye from textile wastewater. Heliyon 5, (2019).

-

Paria, K. & Chakraborty, S. K. Eco-potential of Aspergillus penicillioides (F12): Bioremediation and antibacterial activity. SN Appl. Sci 1 (2019).

-

Baz, A., Elwy, E., Ahmed, W. & El-Sayed, H. Metabolic profiling, antimicrobial, anticancer, and in vitro and in Silico Immunomodulatory investigation of Aspergillus Niger OR730979 isolated from the Western Desert, Egypt. Int. Microbiol. 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10123-024-00503-z (2024).

-

Vaksmaa, A. et al. Role of fungi in bioremediation of emerging pollutants. Front Mar. Sci. 10 (2023).

-

Rajakumar, G. et al. Yttrium oxide nanoparticle synthesis: An overview of methods of preparation and biomedical applications. Appl. Sci. 11, 2172 (2021).

-

Vinayagam, Y., Venkatraman, G. & Vijayarangan, D. R. Sustainable treatment of glass industry wastewater using biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles: Antibacterial and photocatalytic efficacy. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad 200, 106036 (2025).

-

Elhalil, A. et al. Factorial experimental design for the optimization of catalytic degradation of malachite green dye in aqueous solution by Fenton process.Water Resour. Ind. 15, 41–48 (2016).

-

Wouters, R. D. et al. TiO2-NPs/ZnO-NPs@ Co3O4 nanocomposite from natural extracts for the Rhodamine 6G photodegradation. Surf. Interfaces 48 (2024).

-

Kayal Vizhi, D. et al. Evaluation of antibacterial activity and cytotoxic effects of green AgNPs against breast cancer cells (MCF7). Adv. Nano Res. 4, 129–143 (2016).

-

Sridevi, D. V., Devi, R., Jayakumar, K. T. & Sundaravadivel, E. N. PH dependent synthesis of TiO2 nanoparticles exerts its effect on bacterial growth Inhibition and osteoblasts proliferation. AIP Adv. 10 (2020).

-

Mbenga, Y., Adeyemi, J. O., Mthiyane, D. M. N., Singh, M. & Onwudiwe, D. C. Green synthesis, antioxidant and anticancer activities of TiO2 nanoparticles using aqueous extract of tulbhagia violacea. Results Chem. 6 (2023).

-

Rao, K., Ashok, C., Rao, K. & Chakra, C. Green synthesis of TiO2 nanoparticles using hibiscus flower extract. Proc. Int. Conf. Emerg. Technol. 79–82 (2014).

-

Jha, N., Esakkiraj, P., Annamalai, A. & Lakra, A. Synthesis, optimization, and physicochemical characterization of selenium nanoparticles from polysaccharide of Mangrove rhizophora mucronata with. J. Trace Elem. Min. 2, 100019 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank the Vellore Institute of Technology, Vellore, Tamil Nadu, India, for providing laboratory facilities and guidance.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Vellore Institute of Technology. No funding was received from any profit or non-profit organizations.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical clearance is not required for this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vinayagam, Y., Vijayarangan, D.R. Biological applications of yttrium oxide nanocomposites synthesized from Aspergillus penicillioides and their potential role in environmental remediation. Sci Rep 15, 37211 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21104-4

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21104-4