Introduction

In Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART) cycles, the selection of the embryo with the highest chance of implantation is a key factor determining treatment success. Embryo selection has traditionally relied on morphological assessment, including characteristics such as blastomere number, and degree of fragmentation for cleavage-stage embryos, and morphological quality of trophectoderm (TE) and inner cell mass (ICM) for blastocyst-stage embryos1,2,3. The introduction of time-lapse imaging incubators has ushered in a new era, enabling the dynamic evaluation of embryo development through continuous imaging monitoring4. The morphokinetics approach offers insights into cellular divisions, synchrony, and timings, during culture, possibly related with the embryo implantation potential. Additionally, preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A) is increasingly being used for objective embryo selection, allowing for comprehensive screening to identify chromosomal abnormalities, which might cause implantation failure or pregnancy loss5,6,7,8. However, its use in routine faces challenges due to invasiveness, cost, and the need for specialized skills. Morphokinetics data has been used to assess embryo genetic status but consistent predictive parameters have not yet been identified9.

Improvements in embryo culture media have prompted a transition from predominantly cleavage-stage embryo transfer to blastocyst-stage transfer. This transition aims to improve the selection of viable embryos, and to achieve a better synchronization with the optimal implantation window of the endometrium when transferred in a fresh cycle, ultimately resulting in higher live birth rates per embryo transfer10. However, extending culture to the blastocyst stage may reduce the number of embryos available for transfer or freezing11,12without necessarily improving live birth outcomes, as also noted by the NICE guidelines13.

Nowadays, although embryo transfer at blastocyst stage is considered a contemporary “gold standard”, cleavage-stage embryo transfers continue to be widely employed and represent a viable treatment option14mainly when there is a need for flexibility in clinical practices where resources are limited. The continuous use of Day-3 transfers partly arises from lingering concerns raised over the past decade by observational studies, which highlight potential perinatal risks such as preterm birth, low birthweight, and congenital anomalies associated with blastocyst-stage transfers15,16. However, the data remains controversial17.

To select viable embryos at an early stage of development, numerous studies have endeavoured to correlate morphological parameters at the cleavage stage with the probability of achieving the blastocyst stage18,19. Moreover, several classification algorithms have utilized cleavage stage morphokinetics and morphology parameters to predict blastulation20,21and to the likelihood of implantation22. These algorithms may not be universally applicable, as they necessitate the availability of time-lapse incubators to obtain morphokinetic data, which might not be available in every laboratory. It is also essential to acknowledge that the models lack the capacity to predict embryo ploidy, an important parameter for assessing embryo viability.

To overcome this gap, this study aimed to provide a classification system that predicts blastulation and euploidy potential, based on easily accessible patient and Day-3 embryo parameters. The proposed models can serve as a valuable complement to conventional embryo selection methods and may function as an aiding tool for decision-making to prioritize embryos for transfer within any laboratory setup.

Results

Impact of Day-3 embryo morphological characteristics on blastulation and euploidy

The study involved the inclusion of 33,999 embryos originating from 5,702 cycles, from a cohort of 3,075 patients. The overall patient characteristics are presented in Supplemental Table 1. Multilevel models demonstrated that Day-3 cell count was significantly associated with obtaining a biopsiable blastocyst from a Day-3 embryo (Table 1). Embryos with less than 6 cells were significantly less likely to become blastocysts (OR: 0.19, 95% CI: 0.18–0.21, P < 0.0001) compared to embryos with 6–10 cells at Day-3, while those with more than 10 cells were significantly more likely to become blastocysts (OR: 1.22, 95% CI: 1.09–1.36, P < 0.0001). Moreover, fragmentation rate was also associated with the likelihood of becoming a biopsiable blastocyst, and increasing rates of fragmentation were associated with decreased odds of blastulation (56%, 79%, and 88% decreased odds for B, C, and D grade fragmentation compared to A grade fragmentation, P < 0.0001 for all). Table 2 shows the multinomial regression results for factors associated with euploidy, aneuploidy and no blastulation. Regression results showed that cell count had a stronger correlation with embryos failing to reach blastulation when compared to euploids than with aneuploid embryos (Table 2). Increasing degree of fragmentation was associated to blastulation failure, but it did not appear to be a significant indicator for distinguishing between aneuploid and euploid blastocysts in this cohort (Table 2).

Model selection and feature importance

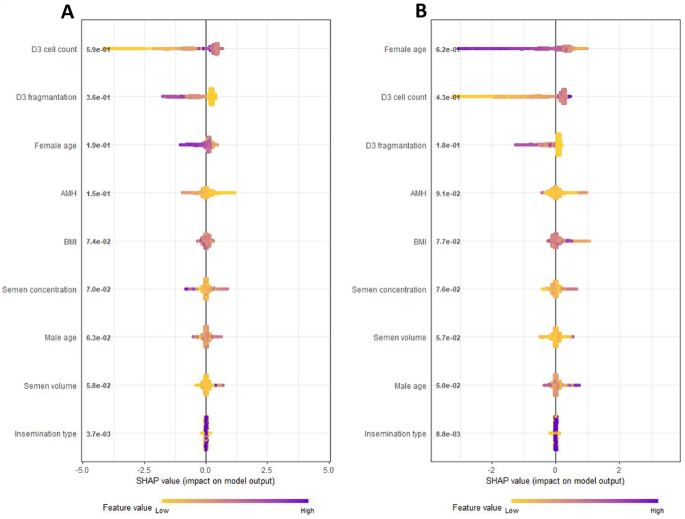

Variables initially considered in the prediction model were female and male age, body mass index, serum anti-Mullerian-Hormone (AMH), semen volume, sperm concentration, insemination type, Day-3 cell count, and fragmentation rate. Ranking of features according to their addition to overall prediction of blastulation and euploidy was assessed with Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP) plots (Fig. 1). SHAP plot for euploidy model ranked top three features as female age, cell count, and fragmentation rate. While the ranking for the biopsiable blastocyst model was slightly different, ranking cell count as top feature followed by fragmentation and female age (Fig. 1). The final models were selected based on multiple performance metrics such as AUC, AUC shrinkage, calibration slope, calibration intercept and correct call rate for blastulation or euploidy. For both blastulation and euploidy models, combination of female age, Day-3 cell count, and fragmentation provided the most parsimonious model without sacrificing performance (Supplemental Tables 2 and 3).

SHAP (Shapley Additive Explanations) plots of biopsiable blastocyst (A) and euploidy (B) models including all candidate variables. Features positioned higher on the plot exert a stronger influence on the model’s prediction, whereas those lower on the plot contribute less. Additionally, feature values at the extremes of the scale tend to impact the prediction more significantly than those near the center.

Validation performance of the final models

In the validation samples, AUC values of blastulation model (AUC: 0.72, 95% CI: 0.71–0.73) and euploidy model (AUC: 0.73, 95% CI: 0.72–0.74) were similar. The calibration of the model was deemed more important for clinical utility (i.e., ranking embryos according to their potential), was assessed with plots and by comparing expected vs. observed rates (Tables 3 and 4). The final model for the euploidy model showed very good calibration up to a 40% predicted euploid blastulation rate, after which the model slightly over predicted the probability (Table 4). The final model for blastulation slightly underpredicted the biopsiable rate in probabilities below 10% and was otherwise well calibrated (Table 3). The final quality tranches were constructed according to calibration performance. Table 3 shows the quality tranches for biopsiable blastocyst model including expected and observed blastulation rates in the tranches over 1000 cross-validation samples, as well as the percentage of embryos falling into each category. Table 4 shows the same information for the euploidy model. In almost all repeat cross-validation samples, there was almost no mixing between quality tranches in terms of observed outcome probabilities, which differed little from the predicted probabilities.

Cycle level performances of the final models were assessed with correct call scores for blastulation, blastocyst with highest inner-cell mass grade and euploid blastulation (Figs. 2 and 3). The correct call scores of the machine learning model for blastulation, blastocyst with highest inner-cell mass grade and euploid blastulation were 37.05 ± 1.89, 30.03 ± 1.72 and 15.75 ± 1.91, respectively. The same scores were 33.13 ± 1.76, 27.26 ± 1.80 and 13.6 ± 1.90 for selecting the embryo with highest cell count and lowest fragmentation approach. The machine learning model obtained higher correct call score in all domains when compared to both random selection and selecting the embryo with highest cell count and lowest fragmentation and all differences were statistically significant (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 3). To make the model outputs of blastulation and euploidy models more interpretable, the predicted probabilities from the machine learning models were shown with heatmap plots (Fig. 4A and B, respectively). Plots were further stratified by female age (25, 30, 35 and 40 years-old). The heatmap plots show the complex non-linear association between the predictor variable and the outcome, that is also influenced by the female age. An online calculator for both models can be found in https://artfertilityclinics.shinyapps.io/GEMMA-D3B/.

Explanation of correct call score. In the example below, green circles represent the embryos with the target outcome and red circles represent the embryos without the target outcomes (i.e., euploidy, blastocyst, blastocysts with the highest inner-cell mass grade within the pool). Embryos that are labelled “1” are the ones selected by the evaluated algorithm. Whenever the algorithm correctly identifies the embryo with the target outcomes, it will gain 1 point and 0 if it doesn’t. The total points algorithm will score divided by the number of cycles would be the initial “Observed (O) call rate”. The maximum number of point it can get is the “Maximum (M) call rate” is the number of cycles with at least one embryo with the target outcome as not all cycles will have one. The lowest acceptable call score would be that of random selection that should roughly correspond to the “Outcome rate (R)” in the cohort. We designed the correct call score so that it is a standardized measure for each cohort. A mean correct call rate of 0 represents the performance of random selection while 100 represents the perfect performance, i.e., selecting the embryo with the target outcome in all cycles with at least one embryo with the target outcome.

Correct call scores for blastulation, blastocysts with highest inner-cell mass grade and euplody blastocyst for the final model, selection of highest cell count and lowest fragmentation and random selection. Random selection is presented by the age only model as female age cannot differentiate embryos within individual pools.

Predicted probabilities from the final model for blastulation (A), and for euploidy (B), stratified by female age. Degree of fragmentation categorized as A (< = 10%), B (11–25%), C (26–35%), D (> 35%).

Discussion

The current study clearly demonstrated that Day-3 morphology features can serve as a valuable tool for classifying embryos in terms of their potential for blastulation and euploidy. The study utilizes a ML algorithm deployed on a dataset of 33,999 embryos, and to the best of our knowledge, the largest dataset known for this purpose. Importantly, the model relies on easily accessible data, including Day-3 cell number and fragmentation rate of cleavage-stage embryos, as well as patient information, a fact that makes the model applicable and accessible across a wide range of settings without need for specialized equipment or proprietary algorithms. This model has demonstrated stable performance in cross-validation samples and has exhibited excellent calibration for ranking of embryos accurately. It can be useful for making informed decisions regarding the selection of embryos with greatest potential for euploidy and blastulation and offers patients insights into their potential euploid embryo pool as early as Day-3 of the culturing process. Moreover, it provides further insight into the importance of Day-3 morphological parameters for predicting blastulation and euploidy.

It has long been demonstrated that blastomere number on Day-3 is an important parameter for predicting the potential of embryos to reach blastulation and of being euploid23. Our data indicates cell count as an important predictor of whether a Day-3 embryo will develop into a blastocyst. Though with a somewhat weaker effect, it also shows an association with euploidy. Whereas a lower number of blastomeres on Day-3 has already been correlated with impaired blastulation and implantation18several studies have demonstrated similar characteristics for fast-growing embryos, i.e. embryos presenting > 8 cells on Day-3 being more likely to be aneuploid24,25,26. Contrary to these findings, our analysis demonstrates that embryos with 6–10 cells and embryos with more than 10 cells on Day-3 exhibit a higher probability of reaching the blastocyst stage and of being euploid. The outcome differences could be mainly due to variations in PGT-A methodology. Previous studies used outdated cleavage-stage embryo biopsies with obsolete genetic technologies, while the present study employed trophectoderm biopsy with NGS. Additionally, the larger sample size of the current study may have contributed to the observed differences between results. As per the ESHRE Istanbul consensus, the ideal Day-3 embryo (68 ± 1 hpi) consists of 8 equally sized mononucleated blastomeres25. However, the consensus also acknowledges that fast-growing embryos, once they reach the blastocyst stage, exhibit similar or even superior developmental potential compared to 8-cell embryos, which aligns with our findings.

Embryo fragmentation rate has been considered one of the essential predictive factors of blastocyst quality and implantation27. Our findings of a negative correlation of fragmentation rate with blastulation and subsequent euploid rate per Day-3 cleaved embryo is in line with previous publications20,28. The present results serve as a plausible explanation for the diminished reproductive outcomes associated with highly fragmented embryos. Although fragmentation is a common event observed during embryo culture, the origins of cellular fragmentation have not yet been completely elucidated. During embryonic cleavage, fragmentation might be originated by extruded blastomeres, apoptotic bodies, persisting polar bodies, extracellular vesicles, cellular portions with chromosome-containing micronuclei29. Furthermore, it has been hypothesized that fragmentation could play a role in regulation and maintenance of cellular homeostasis in human embryos as means to normalize embryonic genetic constitution30. The association between embryo fragmentation and ploidy status had not been thoroughly investigated with novel genetic technologies and neither utilized in a classification model, as performed at the present study. Hence, the conclusions drawn from these studies on the impact of embryo fragmentation on Day-3 and blastocyst euploidy remain contradictory and no consensus has yet been achieved9. Interestingly, our data demonstrate that the lower incidence of euploidy of fragmented embryos on Day-3 is mainly because of a compromised blastulation potential. In other words, when an embryo reaches the blastocyst stage, its chances of being euploid remain unaffected by the fragmentation rate observed on Day-3. Despite the fact that embryos that did not reach blastocyst stage were not biopsied, aneuploidy remains a plausible explanation for the developmental arrest31,32,33,34,35.

Extending embryo culture to the blastocyst stage enables selection of viable embryos by excluding those unlikely to reach this crucial stage, increasing the probability of successful pregnancies36,37,38. However, there remains a theoretical possibility that embryos showing developmental arrest in vitro could thrive in vivo and lead to pregnancy. Consequently, the decision to extend culture to the blastocyst stage may raise the risk of cycle cancellations and a reduction in the quantity of cryopreserved embryos per cycle39,40. Hence, the practice of transferring embryos at the cleavage stage continues to be a widespread approach globally14.

Numerous studies have explored Day-3 morphological and morphokinetic parameters in an attempt to predict embryo viability marked by blastulation, euploidy or reproductive outcomes9,18,41,42,43. In this context, several models and classification algorithms have been published utilizing early embryonic parameters up to Day-3. Conaghan et al. introduced an initial model based on morphokinetic time parameters such as P2 (the duration of the second cell cycle, t3–t2) and P3 (the synchrony between the second and third cell divisions, t4–t3) by time-lapse image analysis, categorizing embryos into ‘high’ or ‘low’ potential for blastocyst development42. An updated version of this algorithm incorporated oocyte age and cell count on Day-3 alongside P2 and P3, assigning embryos a score from 1 to 5 based on their blastocyst potential44. A recent validation of this model showed a significant increase in blastocyst formation rates with higher model scores, but no significant association with euploidy21. Another model, based on cell number, fragmentation, and cellular symmetry, aimed to identify high-quality blastocysts beyond BL3BB. However, it lacked practical tools for external application/validation, detailed specifications of models, and methods to address overoptimism20. A recent deep learning algorithm model, iDAScore, discriminated between embryos that resulted in live birth or no live birth (AUC of 0.627 and 0.607), showed a significant correlation with cell numbers and fragmentation scored manually on Day-2 and Day-3. This illustrates the importance of these parameters on further embryo development and could be a useful tool that is, however, only accessible through a time lapse-incubator since is integrated to the system45.

A strength of the present study compared to previously published models is the utilization of embryo information from 17,714 embryos with PGT-A results by NGS. Moreover, by integrating patient factors and embryo-level characteristics, it enhanced both the blastulation prediction model and the euploidy prediction model. The model was well calibrated with the prediction range covering (5–70) % for blastulation and (2–40) % for euploidy rates. It is further important to emphasize that the large dataset al.lows for data splitting and to obtain realistic performance estimates that is compliant with TRIPOD46. Remarkably, the information required to implement this model is readily accessible within any laboratory setting, obviating the necessity for resource-intensive practices such as time-lapse incubation, dynamic or static imaging and extended culture. The model’s primary clinical utility lies in ranking embryos within a single cohort, where female age, being constant, cannot distinguish between embryos. By leveraging cell count and fragmentation, the model significantly outperformed conventional methods in selecting the embryo with the highest probability of blastulation, and euploidy, as shown by superior “correct call” scores. Female age (any other female level factor) was retained to account for potential interactions but did not improve the correct call score, as it remains constant across embryos within a cohort.

Despite the foreseen effectiveness of the proposed model, one major limitation is that, unlike automatic embryo grading, microscopic assessment of embryo morphology is a subjective procedure susceptible to inter-observers variability47. To maximize the effectiveness of the model, it is crucial to adhere to the Gardner’s grading criteria, which was used for building this prediction tool. A notable limitation of this study is that the dataset used for both model development and validation was derived entirely from a single IVF center. While this ensures consistent laboratory protocols and minimizes intra-laboratory variability, it may limit the applicability of the model to other clinical settings with different embryo grading practices, patient populations, or culture conditions. Therefore, it is prudent to validate the model externally using data from different centres.

Conclusion

In conclusion, as cleavage stage embryo transfers are still often adopted worldwide, our model may assist with ranking Day-3 embryos based on their expected blastulation and euploidy rates, helping thus to allocate resources in a cost-effective manner and increase success rates of the first embryo transfer of an ART cycle. The robustness of our findings, derived from a substantial and diverse dataset, reinforces the potential of leveraging computational tools to enhance embryo selection accuracy. As the field of ART continues to evolve, our prediction model holds the promise of optimizing success rates and facilitating informed decisions, ultimately benefiting patients undergoing fertility treatments.

Methods

Ethical approval

The present study project does not include any interaction or intervention with human subjects or include any access to identifiable private information. Approval for this study was obtained from ART Fertility Clinics LLC Research Ethics Committee (REC) (Research Ethics Committee REFA085). This research was conducted in accordance with the relevant guidelines/regulations, regulating human subject research in Abu Dhabi, UAE. We confirm that the patients signed an informed consent in which they approved the retrospective and anonymous use of their data.

Study design

This was a single centre retrospective study including autologous cycles, between March 2017 and December 2021 in a private assisted reproductive technology centre (ART Fertility Clinics in Abu Dhabi). Embryos were evaluated for cell number and degree of fragmentation on Day-3, 68 ± 1 h post-insemination. Cell count was recorded on a continuous scale unless compacted. Degree of fragmentation was categorized as A (< = 10%), B (11–25%), C (26–35%), D (> 35%). Female patient’s characteristics included age, AMH level and body-mass index (BMI). All expanded blastocysts available on Day-5, Day-6 or Day-7 with existent inner cell mass (ICM) and trophectoderm (TE) cells were subjected to TE biopsy for PGT-A analysis with Next-Generation-Sequencing, and ploidy status was recorded. The primary objective of the study was to develop prediction models for blastocysts of sufficient quality for biopsy and euploid blastocysts by using Day-3 (Day-3) embryo morphology and patient characteristics.

Ovarian stimulation (OS)

Patients underwent ovarian stimulation using standard protocols (GnRH-agonist or GnRH-antagonist). The stimulation medication used was either rec-FSH (recombinant Follicle Stimulating Hormone) or HMG (Human Menopausal Gonadotropin), with dosage adjustments determined by patient-specific factors like age, BMI, AMH, and antral follicle count (AFC)48. Final oocyte maturation was triggered with either hCG (human choriogonadotropin), GnRH-agonist or dual trigger (hCG and GnRH-agonist) once leading follicles reached preovulatory stage and oocyte retrieval was conducted within a timeframe of 34–36 h thereafter.

Oocyte insemination and embryo culture

Oocytes were either inseminated by conventional IVF or ICSI (intracytoplasmic sperm injection), at 40 h post-trigger. Subsequent culture was in either SAGE Quinn’s Advantage Sequential medium (Quinn’s Advantage® Protein Plus Cleavage and Blastocyst media, CooperSurgical) or Life Global single-step medium (Global®Total®LP, CooperSurgical). Embryos were individually cultured in a 30µL droplet of culture medium covered with 8 mL of oil or in 25µL of culture medium in each well covered with 1.4 ml of oil and incubated for up to 7 Days in either a benchtop incubator (K-SYSTEM, CooperSurgical) or a time-lapse incubator (Embryoscope, Vitrolife, USA), respectively, at 37 °C with 6% CO2, 5% O2. On Day-3, for all cleaved embryos, a medium refreshment was conducted, and embryo morphology was evaluated according to the Istanbul consensus guidelines, at approximately 68 ± 1 hpi25 under the inverted microscope or trough images for embryos cultured in TL incubator.

Blastocyst assessment and grading

Blastocysts were evaluated immediately before biopsy and categorized according to a modified Gardner and Schoolcraft criteria49. The grades of expansion were classified such as: BL1 when cavitation started to be visible, BL2 when the cavity was larger than half the volume of the embryo, BL3 when blastocoel filled the blastocyst, BL4 for expanded blastocysts, BL5 when the cells started to herniate through the zona and BL6 for a completely hatched blastocyst. Briefly, a classification of A, B, C and D was annotated for the ICM and TE based on the compactness and cohesiveness of the cells; A: many tightly packed cells, B: loosely grouped cells; C: few loosely grouped cells. Grade D was assigned if very few cells were present or in case of signs of degeneration. Blastocysts were evaluated on Day-5, Day-6 or Day-7 to perform biopsy if possible, according to blastocyst expansion and quality of ICM and TE. Biopsied blastocysts were those reaching a BL3CC quality and above (i.e. when blastocoel filled the blastocyst cavity, and blastocyst contained at least few loosely grouped ICM and TE cells as per Gardner’s criteria49.

Blastocyst biopsy

Blastocysts with quality ≥ BL3CC of development underwent trophectoderm (TE) biopsy for PGT-A by NGS on Day-5, Day-6 or Day-7. A biopsy pipette (Origio, CooperSurgical) possessing an internal diameter of 30 μm was utilized to aspirate three to ten TE cells50. The (TE) cells were gently loosened through the application of a 2.2-ms intensity laser pulse, followed by the complete detachment using a mechanical flicking technique. TE biopsies were washed, placed in 0.2-ml Eppendorf PCR tubes containing 2.5 µl phosphate-buffered saline, and stored at −20 °C until further processing.

Preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidies of TE samples

Whole genome amplification protocol was applied on all TE samples, employing PicoPlex technology (Rubicon Genomics, Inc., USA). Subsequently, the process involved the preparation of individual Libraries, wherein distinct barcodes were integrated to label the amplified DNA from each sample. For sequencing, a 316 or 318 chip was employed in conjunction with the Personal Genome Machine sequencing technology (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) after amplification and enrichment of the DNA. The analysis and interpretation of sequencing data were conducted using ion Reporter™ software (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Statistical analysis

Patients’ characteristics are presented by median, and IQR (inter-quartile) ranges for continuous variables and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. To analyse the association of embryo level factors with outcomes, regression analyses were performed using multilevel logistic or multinomial models with random intercepts for embryos from the same cycles and cycles of the same couple. Logistic regression analyses were performed for comparison of no blastulation vs. blastulation and multinominal analyses were also run to show the effect on each outcome strata (euploid vs. no blastulation and euploid vs. aneuploid/all mosaics). The candidate variable pool consisted female and male age, body mass index, AMH, sperm volume, sperm concentration, insemination type, Day-3 cell count, and fragmentation rate. These metrics includes the most popular patient and embryo level variables that are commonly obtained in IVF treatment centres and those which are often associated with success chance. The largest missing values in the candidate variable set were observed in AMH (3.2%) and there were no significant distributional differences of variables between groups with and without any missingness. While it is not possible to rule-out missing not at random structure, we believe it was reasonable to assume missing at random, i.e., missingness is conditioned on the observable data, in our case and we imputed the missing values using multiple imputation by chained equations.

Development of the prediction model

Prediction models were built using a classification and regression trees approach (XGBoost) [51]. Model discovery and testing was done with repeated 2-fold cross-validation. Dataset split was made based on random allocation of cycles rather than embryos so that model was trained and tested on different patients using data from all day 3 embryos. Tuning parameters were selected to achieve stable overall performance among each paired training and test set and between repeated samplings. Considered performance metrics at large were area under the receiver operating characteristic curves (AUC), AUC shrinkage, calibration intercept, calibration slope and Brier scores. Considering population level performance metrics may not reflect embryo selection on a cycle level, we also assessed the correct call rate (agreement of predicted and observed outcome) for the highest scoring embryo in each cycle.

The ratio was scaled by using correct call rate by random selection and correct call rate by making the correct call in each possible cycle within there was at least one embryo with the target outcome (blastulation or euploidy). Scaling was performed so that the mean score is between 0 and 100, 0 indicating random selection performance and 100 indicating perfect selection for that outcome (Fig. 2). This metric was only calculated for cycles with more than one cleavage stage embryo. All performance metrics were tested initially with 200 repeated 2-fold cross validation samples to determine the final model. A maximum shrinkage of 5.0% in AUROC values was targeted between training and validation sets.

After the final model has been selected and tuning parameters are set, all reported performance metrics were obtained from 1000 repeated 2-fold cross-validation samples to adjust for overoptimism. We also tested the final machine learning models against a simpler scoring approach that selects the embryo with best characteristic in each parameter (i.e., lowest fragmentation, highest cell count) (Fig. 3). We believe this approach may resemble routine clinical practice and provide further evidence on whether more complex approaches with a machine learning model is needed or not.

The primary aim of the model was to create embryo quality tranches for biopsiable and euploidy blastocysts that accurately reflect their predicted and observed rates in the validation samples. After determining the model structures and tuning parameters, the final models were obtained by retraining on the whole dataset. An online calculator was deployed for external use and further validation (https://artfertilityclinics.shinyapps.io/GEMMA-D3B/).

Data availability

The authors confirm that all relevant data are included in the paper and/or its supplementary information files.

References

-

Shulman, A. et al. Relationship between embryo morphology and implantation rate after in vitro fertilization treatment in conception cycles. Fertil. Steril. 60, 123–126 (1993).

-

Ai, J. et al. The morphology of inner cell mass is the strongest predictor of live birth after a Frozen-Thawed single embryo transfer. Front. Endocrinol. 12, 621221 (2021).

-

Lou, H. et al. Association between morphologic grading and implantation rate of euploid blastocyst. J. Ovarian Res. 14, 18 (2021).

-

Meseguer, M. et al. The use of morphokinetics as a predictor of embryo implantation. Hum. Reprod. 26, 2658–2671 (2011).

-

Diedrich, K., Fauser, B. C. J. M., Devroey, P. & Griesinger, G. The role of the endometrium and embryo in human implantation. Hum. Reprod. Update. 13, 365–377 (2007).

-

Campos-Galindo, I. et al. Molecular analysis of products of conception obtained by hysteroembryoscopy from infertile couples. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 32, 839–848 (2015).

-

Neal, S. A. et al. Preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy is cost-effective, shortens treatment time, and reduces the risk of failed embryo transfer and clinical miscarriage. Fertil. Steril. 110, 896–904 (2018).

-

Tiegs, A. W. et al. A multicenter, prospective, blinded, nonselection study evaluating the predictive value of an aneuploid diagnosis using a targeted next-generation sequencing–based preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy assay and impact of biopsy. Fertil. Steril. 115, 627–637 (2021).

-

Bamford, T. et al. Morphological and morphokinetic associations with aneuploidy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum. Reprod. Update. 28, 656–686 (2022).

-

Clua, E. et al. Blastocyst versus cleavage embryo transfer improves cumulative live birth rates, time and cost in oocyte recipients: a randomized controlled trial. Reprod. Biomed. Online. 44, 995–1004 (2022).

-

Blastocyst culture. And transfer in clinical-assisted reproduction: a committee opinion. Fertil. Steril. 99, 667–672 (2013).

-

Glujovsky, D. & Farquhar, C. Cleavage-stage or blastocyst transfer: what are the benefits and harms? Fertil. Steril. 106, 244–250 (2016).

-

O’Flynn, N. Assessment and treatment for people with fertility problems: NICE guideline. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 64, 50–51 (2014).

-

Glujovsky, D. et al. Cleavage-stage versus blastocyst-stage embryo transfer in assisted reproductive technology. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2022). (2022).

-

Wang, X. et al. Comparative neonatal outcomes in Singleton births from blastocyst transfers or cleavage-stage embryo transfers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 15, 36 (2017).

-

Alviggi, C. et al. Influence of cryopreservation on perinatal outcome after blastocyst- vs cleavage‐stage embryo transfer: systematic review and meta‐analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gyne. 51, 54–63 (2018).

-

Raja, E. A., Bhattacharya, S., Maheshwari, A. & McLernon, D. J. A comparison of perinatal outcomes following fresh blastocyst or cleavage stage embryo transfer in singletons and twins and between singleton siblings. Human Reproduction Open hoad003 (2023). (2023).

-

Luna, M. et al. Human blastocyst morphological quality is significantly improved in embryos classified as fast on Day-3 (≥ 10 cells), bringing into question current embryological dogma. Fertil. Steril. 89, 358–363 (2008).

-

Tan, J. H., Chen, J. J., Lim, L. J. & Wong, P. S. The impact of in vitro human embryo fragmentation on blastocyst development and ploidy using Next-Generation sequencing (NGS). Reprod. Biomed. Online. 38, e23 (2019).

-

Yu, C., Zhang, R. & Li, J. A, Z.-C. A predictive model for high-quality blastocyst based on blastomere number, fragmentation, and symmetry. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 35, 809–816 (2018).

-

Valera, M. A. et al. Clinical validation of an automatic classification algorithm applied on cleavage stage embryos: analysis for blastulation, euploidy, implantation, and live-birth potential. Hum. Reprod. 38, 1060–1075 (2023).

-

Theilgaard Lassen, J., Fly Kragh, M., Rimestad, J., Nygård Johansen, M. & Berntsen, J. Development and validation of deep learning based embryo selection across multiple days of transfer. Sci. Rep. 13, 4235 (2023).

-

Shapiro, B. S., Harris, D. C. & Richter, K. S. Predictive value of 72-hour blastomere cell number on blastocyst development and success of subsequent transfer based on the degree of blastocyst development. Fertil. Steril. 73, 582–586 (2000).

-

Magli, M. C. et al. Embryo morphology and development are dependent on the chromosomal complement. Fertil. Steril. 87, 534–541 (2007).

-

Alpha Scientists in Reproductive Medicine and ESHRE Special Interest Group of Embryology et al. The Istanbul consensus workshop on embryo assessment: proceedings of an expert meeting. Hum. Reprod. 26, 1270–1283 (2011).

-

Kroener, L. L. et al. Increased blastomere number in cleavage-stage embryos is associated with higher aneuploidy. Fertil. Steril. 103, 694–698 (2015).

-

Rhenman, A. et al. Which set of embryo variables is most predictive for live birth? A prospective study in 6252 single embryo transfers to construct an embryo score for the ranking and selection of embryos. Hum. Reprod. 30, 28–36 (2015).

-

Ebner, T. et al. Embryo fragmentation in vitro and its impact on treatment and pregnancy outcome. Fertil. Steril. 76, 281–285 (2001).

-

Cecchele, A., Cermisoni, G. C., Giacomini, E., Pinna, M. & Vigano, P. Cellular and molecular nature of fragmentation of human embryos. IJMS 23, 1349 (2022).

-

Coticchio, G. et al. Plasticity of the human preimplantation embryo: developmental dogmas, variations on themes and self-correction. Hum. Reprod. Update. 27, 848–865 (2021).

-

Magli, M. C. Chromosome mosaicism in Day-3 aneuploid embryos that develop to morphologically normal blastocysts in vitro. Hum. Reprod. 15, 1781–1786 (2000).

-

Sandalinas, M. et al. Developmental ability of chromosomally abnormal human embryos to develop to the blastocyst stage. Hum. Reprod. 16, 1954–1958 (2001).

-

Rubio, C. et al. Chromosomal abnormalities and embryo development in recurrent miscarriage couples. Hum. Reprod. 18, 182–188 (2003).

-

Li, M. et al. Fluorescence in situ hybridization reanalysis of day-6 human blastocysts diagnosed with aneuploidy on Day-3. Fertil. Steril. 84, 1395–1400 (2005).

-

De Munck, N. et al. Segmental duplications and monosomies are linked to in vitro developmental arrest. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 38, 2183–2192 (2021).

-

Gardner, D. K. et al. A prospective randomized trial of blastocyst culture and transfer in in- vitro fertilization. Hum. Reprod. 13, 3434–3440 (1998).

-

Papanikolaou, E. G. Live birth rate is significantly higher after blastocyst transfer than after cleavage-stage embryo transfer when at least four embryos are available on Day-3 of embryo culture. A randomized prospective study. Hum. Reprod. 20, 3198–3203 (2005).

-

Papanikolaou, E. G. et al. In vitro fertilization with single Blastocyst-Stage versus single Cleavage-Stage embryos. N Engl. J. Med. 354, 1139–1146 (2006).

-

Tsirigotis, M. Blastocyst stage transfer: pitfalls and benefits. Too soon to abandon current practice? Hum. Reprod. 13, 3285–3289 (1998).

-

Marek, D. et al. Introduction of blastocyst culture and transfer for all patients in an in vitro fertilization program. Fertil. Steril. 72, 1035–1040 (1999).

-

Moayeri, S. E. et al. Day-3 embryo morphology predicts euploidy among older subjects. Fertil. Steril. 89, 118–123 (2008).

-

Conaghan, J. et al. Improving embryo selection using a computer-automated time-lapse image analysis test plus Day-3 morphology: results from a prospective multicenter trial. Fertil. Steril. 100, 412–419e5 (2013).

-

Wu, J., Zhang, J., Kuang, Y., Chen, Q. & Wang, Y. The effect of Day-3 cell number on pregnancy outcomes in vitrified-thawed single blastocyst transfer cycles. Hum. Reprod. 35, 2478–2487 (2020).

-

Bettina Frank, M. Kg. Merck Serono Introduces New Eeva Test Version Aiming for Optimized Assisted Reproductive Outcomes. (2015).

-

Ahlström, A. et al. Correlations between a deep learning-based algorithm for embryo evaluation with cleavage-stage cell numbers and fragmentation. Reprod. Biomed. Online. 47, 103408 (2023).

-

Collins, G. S., Reitsma, J. B., Altman, D. G. & Moons, K. G. M. Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD): the TRIPOD statement. BMJ 350, g7594–g7594 (2015).

-

Baxter Bendus, A. E., Mayer, J. F., Shipley, S. K. & Catherino, W. H. Interobserver and intraobserver variation in Day-3 embryo grading. Fertil. Steril. 86, 1608–1615 (2006).

-

The ESHRE Guideline Group on Ovarian Stimulation et al. ESHRE guideline: ovarian stimulation for IVF/ICSI†. Human Reproduction Open et al. hoaa009 (2020). (2020).

-

Gardner, D. K. & Wbg, S. D. In-Vitro Culture of Human Blastocysts (Parthenon, 1999).

-

Capalbo, A. et al. Correlation between standard blastocyst morphology, euploidy and implantation: an observational study in two centers involving 956 screened blastocysts. Hum. Reprod. 29, 1173–1181 (2014).

-

Chen, T., Guestrin, C. & XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. in Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining 785–794ACM, San Francisco California USA, (2016). https://doi.org/10.1145/2939672.2939785

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Elkhatib, I., Kalafat, E., Bayram, A. et al. Blastulation and ploidy prediction using morphology assessment in 33,999 day-3 embryos. Sci Rep 15, 43475 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19898-4

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

Version of record:

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19898-4