It’s natural to crave sugar when you feel tired and want a boost of energy. Now scientists at Columbia University’s Zuckerman Institute have linked a brain area in mice to the drive to consume not just sweets, but fats, salt, and food. The findings show this area, called the bed nucleus of the stria-terminalis (BNST), serves as a kind of dial that can amplify or repress consumption, and that manipulating BNST activity impacts on consummatory responses.

The study may inform novel treatments for both overeating and undereating. The results suggest, for example, that finding ways to modulate this brain circuit may help treat the severe loss of appetite and muscle wasting that is not uncommonly experienced by patients undergoing chemotherapy.

“The relationship between something that stimulates the appetite, such as fat or sugar, and its capacity to drive us to consume it has been an open question in neuroscience,” said Charles S. Zuker, PhD, a principal investigator at Columbia’s Zuckerman Institute and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator. “This work provides exciting new insights and identifies a brain center that orchestrates a unified control over consummatory behaviors.”

Zuker is corresponding author of the team’s published paper in Cell, titled “A brain center that controls consummatory responses,” in which they wrote, “… we demonstrate that the BNST functions as a central hub, transforming appetitive signals into consumption and linking sensory inputs to the internal state, not only for sweet but also for other stimuli such as salt or food, to flexibly regulate consummatory behaviors.”

“The sense of taste functions as the primary gateway controlling ingestive behaviors,” the authors wrote. For their newly reported study, Zuker and colleagues set out to analyze the brain circuit in mice that responds to sweet tastes. Their goal was to explore how a sensation that can stimulate the appetite spurs the urge to consume. “We reasoned that there may be a general ‘brain dial’ for consumption across stimuli and a common neural substrate for matching consummatory responses with specific internal needs,” they explained.

The scientists first investigated the amygdala, the brain’s emotion center, which also helps judge whether various sensations feel good or bad. “Previously, we showed that the amygdala imposes valence on taste stimuli (e.g., attraction to sweets and aversion to bitters),” the team explained. “We reasoned that identifying the amygdala neurons responding to sweet would provide an entry to dissect the circuit that translates appetitive signals into consummatory responses. This, in turn, would allow us to define circuits linking the internal state to consumption.”

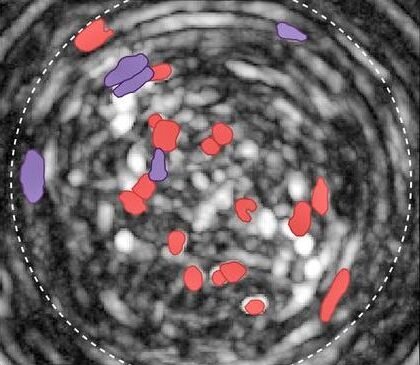

The investigators identified neurons in the central amygdala that were activated by sweetness. Each of those neurons possessed branches that reached into the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST), which prior work had found was associated with feeding and responses to rewards. “The BNST has been linked to reward processing, motivated behaviors, and feeding; thus, we chose it as a candidate for mediating sweet-evoked consummatory responses,” the authors commented.

When the researchers stimulated neurons connected to the BNST, they showed that mice that had recently fed until they were full could now be driven to continue to consume sweets. Conversely, suppressing the BNST neurons greatly suppressed sweet consumption even in animals that were very hungry.

The scientists went on to show that this brain region was associated with the urge to consume not just sweets, but also salt, fat, food, and other substances. “Our discovery far exceeded our expectations,” said Li Wang, PhD, the study’s co-lead author and a postdoctoral fellow in the Zuker lab. “We did not expect this brain region to be so important and involved with such a broad range of consummatory behaviors in such a general way.”

The scientists uncovered anatomical connections between the BNST and other parts of the brain that underscore its role in consumption. For example, they found links between the BNST and brain circuits sensing an animal’s internal states, such as the need to eat when hungry or to consume salt when their body’s salt levels become dangerously low.

“We now have a better understanding of how the brain integrates specific internal needs with sensory signals in order to elicit appropriate consummatory responses,” said José A. Cánovas, PhD, the study’s co-lead author and a postdoctoral fellow in the Zuker lab.

This discovery of a “brain dial” for consumption might one day help cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy, who often experience cachexia, a condition that can lead to a dangerous loss of appetite and weight. When mice were given a chemotherapy drug that can trigger a cachexia-like state, the researchers found that stimulating the BNST could protect them from weight loss.

“Chemotherapy drugs are amazing in that they can kill cancer, but they also suppress the motivation to eat, which becomes a big problem,” Wang said. “Maybe stimulating this brain area can help address this issue.”

On the flip side, the researchers discovered that inhibiting the BNST resulted in substantial weight loss in mice. The scientists also found the weight-loss drug semaglutide (which is sold under brand names such as Ozempic and Wegovy) targets neurons in the BNST, shedding light on how it may work to help people reduce consumption. These results, they pointed out, “… suggest the BNST may be an important component and a target of the weight-loss effects of GLP1R agonists.”

“Taking semaglutide can lead to nausea and other negative side effects,” Cánovas said. “Perhaps a better understanding of the BNST may lead to therapies that help suppress consumption without these effects.”

In conclusion, the authors wrote, “Together, these findings illustrate how the internal state modulates sensory responses, characterize a general brain dial for consumption, and provide fresh insights into sites of action of GLP1R agonists and a strategy to help promote weight gain in pathological states.”

The post Brain Region Identified as “Dial” That Can Amplify or Repress Consumption in Mice appeared first on GEN – Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology News.