Introduction

For many years, a prevailing belief in the community has been that epoxides are exclusively derived from petroleum, without realising the negative environmental impact associated with their use1. Most conventional epoxides are composed of petroleum-based components, including polyols. Unfortunately, the use of petroleum-based polyols has the potential to pollute the environment and disrupt marine ecosystems and terrestrial habitats2. Consequently, there is a pressing need for sustainable and environmentally friendly alternatives, such as bio-based epoxides and polyols, to address the depletion of crude oil reserves while safeguarding the environment3. Palm oleic acid is a refined fraction obtained as a by-product during the physical refining and distillation of palm oil, particularly from the palm fatty acid distillate (PFAD) stream. This C18:1-enriched fatty acid is separated through short-path molecular distillation or fractional vacuum distillation and is widely available in Malaysia due to the scale of palm oil processing. Its utilization in epoxidation studies offers several advantages: (i) it contains a single monounsaturated double bond, allowing controlled and targeted epoxidation; (ii) it avoids the complexity of triglyceride structures and impurities present in crude oils or UVO; and (iii) it adds value to an industrial by-product, reinforcing the green chemistry and circular economy approach of this work. The epoxidation process can be carried out using various oxidizing agents, such as peracids and peroxides4.

Epoxidised vegetable oils play a crucial role in the industry, serving as lubricants5, intermediates for polymers used in standard syntheses6, plasticisers7, and scavengers8. These oils offer a sustainable alternative to petroleum-based materials for various applications, making them a desirable option for manufacturing epoxy. Additionally, they possess several advantages, such as being non-toxic, biodegradable, and safer for human health and the environment than their petroleum-based counterparts9. The reaction involves using a nucleophile, such as a polyol, to attack the electrophilic carbon in the epoxide ring, resulting in the formation of a hydroxyl group and the opening of the ring. Polyols can be derived from epoxidised vegetable oils, which are commonly used in the production of polyurethane foams, coatings, and adhesives. To form polyols, epoxidized vegetable oils can undergo ring-opening reactions with various nucleophiles, including water, alcohols, and amines10. These polyols have shown promising properties such as high reactivity, excellent mechanical properties, and good thermal stability, making them a viable alternative to petroleum-based polyols11,12. Epoxidation of used oil via in situ catalytic hydrolysis offers a safer and more selective route to biopolyol compared to transesterification, direct hydroxylation, and ozonolysis. This method allows targeted conversion of double bonds into oxirane rings, followed by controlled ring-opening to introduce hydroxyl groups13. Unlike ozonolysis, which involves hazardous reagents or direct hydroxylation with low selectivity, epoxidation ensures better efficiency and product quality. It also surpasses transesterification, which lacks sufficient hydroxylation. Using waste oil adds value and supports sustainable, circular practices. Pre-synthesised peracids offer better control but involve extra steps and safety concerns. In contrast, in situ peracid formation is safer, simpler, and more sustainable, though it may require careful reaction optimization.

Accurate measurement of the interfacial area is crucial as it directly impacts the kinetics of interfacial reactions14. However, there are limited studies on the formation of bio-polyols using in situ hydrolysis of epoxidised palm oleic acid. Additionally, the method has drawbacks, such as the need to repeat all 16 experiments and analyze the bio-polyols product using hydroxyl value analysis, which is impractical and results in high chemical consumption. To overcome these challenges, a process model was developed using MATLAB to determine the reaction kinetics and yield of bio-polyols. This was achieved by utilising data from the 16 previously conducted experiments on the in situ hydrolysis of epoxidised palm oleic acid. The process model offers a more practical approach to obtaining accurate bio-polyol concentrations, eliminating the need for repeated experiments and reducing chemical consumption15.

Titanium dioxide was chosen due to its strong oxidative properties, chemical stability, low toxicity, and affordability. Its surface acidity and ability to facilitate electron transfer enhance the formation of peracids and epoxidation efficiency. These properties are well-documented in previous studies, which support their suitability for green catalytic systems16. The epoxidation of vegetable oils is complex compared to the epoxidation of unsaturated fatty acids, as it produces various epoxidized products depending on the origin of the seed oil17. Oleic acid is a favoured component in vegetable oil, as it is thermally stable, unlike polyunsaturated fats, which produce epoxides. However, studies on bio-polyols produced via in situ hydrolysis of epoxidized oleic acid are limited compared to those focusing on in situ hydroxylation. Therefore, the objectives of this manuscript are (1) to develop a kinetic model for the catalytic epoxidation of palm oleic acid using the particle swarm method in MATLAB and (2) to optimize reaction parameters for bio-polyols production via in situ hydrolysis using the Taguchi Method. The Taguchi method was applied to systematically optimise reaction parameters with minimal experimental runs, enabling the identification of the most influential factors affecting oxirane yield.

Materials and methods

Chemical and materials

Palm oleic acid with a determined purity of 75% (Chemiz (M) Sdn. Bhd) by gas chromatography analyses was purchased and used without pre-treatment. The necessary chemicals, including formic acid (95%), acetic acid (96%), hydrogen peroxide (50%), and titanium dioxide, were sourced from either QReC Sdn. Bhd or Merck Sdn. Bhd.

Kinetic model of epoxidation of palm oleic acid with applied heterogeneous catalyst

The kinetic data were described using a kinetic model based on the assumption that the epoxidation process occurs in a single phase. The single-phase reaction assumption simplifies kinetic modelling by treating the reaction mixture as homogeneous, thereby avoiding interfacial mass transfer limitations. In addition, they reported that the reaction was not affected by mass transfer limitations within the stirring speed range of 150 to 450 rpm under optimal reaction temperature and catalyst loading conditions18. Therefore, in this study, a moderate stirring speed was selected to ensure that the reaction proceeded under kinetic control. The epoxidation process involves two primary reactions: the in situ formation of performic acid (as described in Eq. 1) and the formation of epoxide and biopolyols (as indicated in Eqs. 2 and 3). The MATLAB code outlines the development and optimization of a kinetic model for the catalytic epoxidation of oleic acid, integrating simulation and parameter estimation. The objective function evaluates the root-mean-square error between experimental and simulated concentrations, employing ode45 to solve the reaction kinetics. A Genetic Algorithm (GA) is used to optimise the rate constants by minimising this error, with initial concentration values and experimental data as inputs. The optimized rate constants are then validated by simulating concentration profiles and comparing them with experimental results. The fourth-order Runge-Kutta method was employed to solve the differential equations due to its accuracy and stability in modelling complex reaction kinetics.

$$:text{F}+text{H}:rightleftharpoons::text{P}+text{W}text{a}text{t}text{e}text{r}$$

(1)

$$:text{P}+text{O}text{A}:xrightarrow{::{k}_{2::}}:::text{E}+text{F}$$

(2)

$$:text{E}+:text{W}text{a}text{t}text{e}text{r}xrightarrow{::{k}_{3::}}text{P}text{o}text{l}text{y}text{o}text{l}text{s}$$

(3)

Where F, H, P, OA, and E represent formic acid, hydrogen peroxide, performic acid, oleic acid, and epoxidized palm oleic acid, respectively, the set of simultaneous differential equations is given as Eqs. 4–10. The model serves as the basis for simulating reaction kinetics, integrating differential equations, initial conditions, and boundary constraints to represent the catalytic epoxidation process accurately.

$$:frac{dleft[text{F}right]}{dt}={-k}_{11}left[text{F}right]left[Hright]+{k}_{12}left[text{P}right]left[text{W}text{a}text{t}text{e}text{r}right]+{k}_{2}left[text{P}right]left[text{O}text{A}right]::$$

(4)

$$:frac{dleft[text{H}right]}{dt}=-{k}_{11}left[text{F}right]left[text{H}right]+{k}_{12}left[text{P}right]left[text{W}text{a}text{t}text{e}text{r}right]$$

(5)

$$:frac{dleft[text{P}right]}{:dt}={+k}_{11}left[text{F}right]left[text{H}right]-{k}_{12}left[text{P}right]left[text{W}text{a}text{t}text{e}text{r}right]-{k}_{2}left[text{P}right]left[text{O}text{A}right]$$

(6)

$$:frac{dleft[text{W}text{a}text{t}text{e}text{r}right]}{dt}={+k}_{11}left[text{F}right]left[text{H}right]-{k}_{12}left[text{P}right]left[text{W}text{a}text{t}text{e}text{r}right]-{k}_{3}left[text{E}right]left[text{W}text{a}text{t}text{e}text{r}right]$$

(7)

$$:frac{dleft[text{O}text{A}right]}{dt}=-{k}_{2}left[text{P}right]left[text{O}text{A}right]$$

(8)

$$:frac{dleft[text{E}right]}{dt}=+{k}_{2}left[text{P}right]left[text{O}text{A}right]-{k}_{3}left[text{E}right]left[text{W}text{a}text{t}text{e}text{r}right]$$

(9)

$$:frac{dleft[text{P}text{o}text{l}text{y}text{o}text{l}right]}{dt}={+k}_{3}left[text{E}right]left[text{W}text{a}text{t}text{e}text{r}right]$$

(10)

These constants were obtained through regression analysis, a process that involves fitting experimental data to a mathematical model to estimate the relationship between variables. In this process, the parameters (constants) were optimised to minimise the discrepancy between the experimental data points and the model’s predictions, as shown in Eq. 11.

$$:e=sum:_{i=1}^{n}frac{left|{text{E}}_{i}^{sim}-{text{E}}_{i}^{exp}right|}{n}$$

(11)

where (:{text{E}}_{i}^{sim}) and (:{text{E}}_{i}^{exp}) denote the estimated and experimental epoxy concentrations, (:i) is the ith data point, and (:n) is the total number of data points in the simulations and experiments.

Epoxidation and ring opening by in situ hydrolysis

A mixture containing 100 g of palm oleic acid and a specific molar ratio of formic acid to oleic acid was prepared. The mixture was heated to the required temperature while stirring at a designated speed, and titanium dioxide was used as a catalyst. A 50% hydrogen peroxide solution was added dropwise to the mixture. The epoxidation process continued until bio-polyol was obtained. The in situ hydrolysis process was considered complete when the RCO value approached zero, indicating the degradation of oxirane into polyol.

The optimization process using the Taguchi method

The parameters were investigated at different levels, as outlined in Table 1. Since the objective of the experiment was to maximise the selectivity of the desired product, the ‘larger-the-better’ signal-to-noise (S/N) ratio was employed to identify the control factors that could minimise variability.

The diversity of factors was examined by employing an orthogonal array to cross the control parameters, as illustrated in Table 2. The parameters were selected based on insights and findings from previous reports3,7.

Relative conversion to oxirane (RCO)

The experiment aimed to determine the RCO value by estimating the oxirane oxygen content (OOC) through both theoretical calculations and empirical methods, following the American Oil Chemists Society (AOCS) Official Method Cd 9–5719. The RCO Eq. (12) combines both the theoretical (13) and empirical (14) OOC values.

$$:RCO=:frac{{OOC}_{experiment}}{{OOC}_{theoretical}}:x:100$$

(12)

$$:OO{C}_{the}=left{left(frac{{X}_{0}}{{A}_{i}}right)/left[100+left(frac{{X}_{0}}{{2A}_{i}}right)left({A}_{o}right)right]right}x{:A}_{o}:x100$$

(13)

$$:{OOC}_{Exp}=1.6:x:N:xfrac{(V-B)}{W}:::$$

(14)

XO, Ai, AO, N, V, and W represent the initial iodine value, t molar mass of iodine, molar mass of oxygen, HBr’s normality, HBr solution volume, and sample weight, respectively.

Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy

The brand and model for the FTIR equipment used in this study are Bruker Vertex 70. The first step in this analytical process was the sample preparation. After that, the baseline correction was performed to prevent interference from other background signals. Next, the FTIR spectrometer undergoes a calibration process to ensure precise measurements for the sample. The data collection is a result of the interaction between the sample and infrared radiation, which causes molecular vibrations that the FTIR spectrometer detects.

Result and discussion

Kinetic modelling of the epoxidation process

Based on the setup experiment procedure to produce bio polyol, the reaction rate constant (k) and the bio polyol concentration have been identified. Almost 16 previous experimental data sets were collected to determine the relative conversion of oxirane, known as the ring opening of epoxide, which indicates the structural change of epoxidized oleic acid in becoming a bio-polyol20. In this experiment, the most important factor in determining the bio-polyol concentration is the value of the reaction rate constant (k) for oleic acid epoxidation. That is because bio-polyols can be formed through in situ hydrolysis of epoxidized oleic acid.

A kinetic model for catalytic epoxidation of oleic acid was developed for this study using MATLAB simulation. Table 3 presents the sixteen data experiments executed in the simulation to determine the optimal value of epoxidation.

Validation of the kinetic model

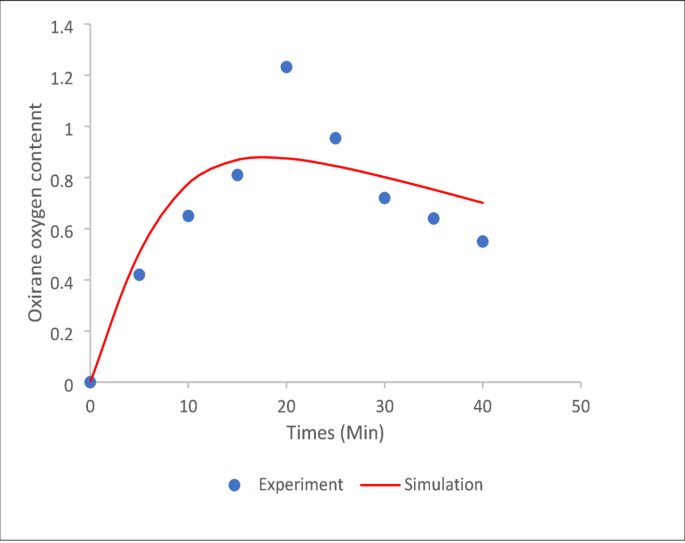

Figure 1 compares the epoxide concentration obtained from experimental data and simulation results. The simulation aligns well with the experimental data during the initial phase, effectively capturing epoxide formation for approximately 15 min. This close agreement highlights the model’s reliability in simulating reaction kinetics during the epoxidation process and supports its suitability for evaluating bio-polyol kinetic rates and concentrations.

However, noticeable deviations occur during the degradation phase, particularly after 20 min, where the simulated values are higher than the experimental results. This suggests that the model may lack certain elements, such as secondary reaction pathways or degradation mechanisms, which become significant in the later stages of the reaction. Possible causes of this divergence could include oversimplified assumptions in the kinetic framework or experimental variations, such as catalyst efficiency or temperature fluctuations.

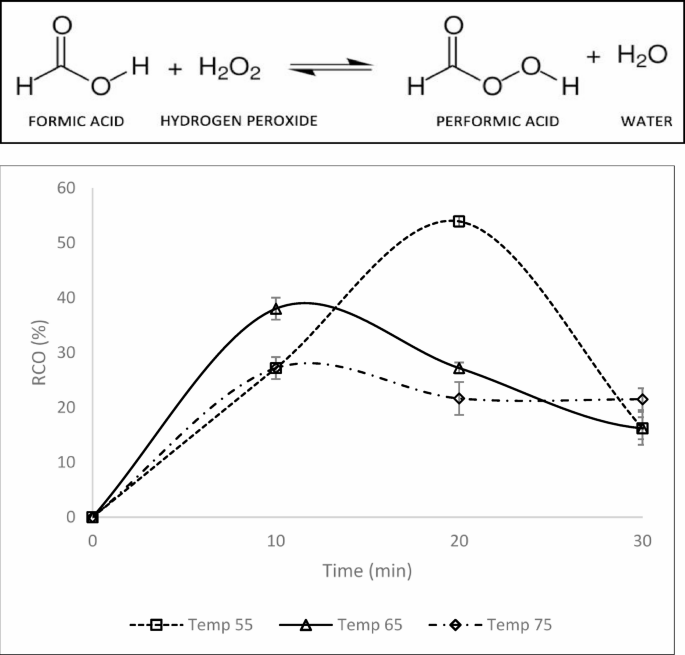

Figure 2 shows the concentration of bio-polyol obtained by the kinetic model throughout the experiment. The hygroscopic characteristic of titanium results in the absorption of water21, which maintains the equilibrium constant (Keq). This creates more performic acid, resulting in a higher RCO. When the equilibrium favouring the creation of performic acid isn’t achieved, it starts to break down, reducing its concentration while increasing the water content in the system22. The initial phase shows a steep increase in concentration, indicating rapid bio-polyol formation as the reaction progresses. This sharp rise highlights the efficient conversion of reactants, likely driven by favorable reaction conditions and kinetics. After this initial phase, the curve gradually levels off, reaching a steady state, which suggests that the reaction has either approached equilibrium or the reactants have been nearly depleted.

The steady state observed in the later phase indicates that further reaction progress is limited, possibly due to the exhaustion of reactants, reduced catalyst activity, or other constraints within the reaction system. This behavior highlights the importance of optimizing reaction parameters, such as catalyst dosage and reaction time, to maximize bio-polyol yield. The concentration profile provides essential insights into the efficiency and kinetics of the process, serving as a guide for further optimisation and refinement.

Figures 1 and 2 indicate that residence time has a strong influence on epoxide and polyol formation. The oxirane content peaks at around 15–20 min (Fig. 1), after which degradation is likely to occur. Similarly, polyol concentration rises quickly within the first 100 min and then plateaus (Fig. 2), suggesting limited benefit from extended reaction time. Therefore, an optimal residence time within this range ensures a high yield and minimises unwanted side reactions.

Optimization of process parameters by the Taguchi method

Signal-to-Noise ratio

Based on the S/N ratios plotted for each process parameter at three levels (Table 4; Fig. 3), it can be assumed that the maximum epoxide yield occurred at the following optimum process parameters: (A) stirring speed: 450 rpm, (B) reaction temperature: 50 °C, (C) hydrogen peroxide/palm oleic acid molar ratio: 1.5:1, and (D) formic acid/palm oleic acid molar ratio: 1.5:1. The 95% confidence intervals for the fitted kinetic parameters are included to reflect the precision and reliability of the model estimates.

Analysis of variance

The contribution percentage was determined to assess the impact of each process parameter on the epoxide yield. ANOVA results (Table 5) show that stirring speed had the most significant effect on epoxide yield (78.18%), followed by hydrogen peroxide/palm oleic acid molar ratio (14.09%), formic acid/palm oleic acid molar ratio (3.97%), and reaction temperature (3.79%). The reaction temperature made the least contribution, adjusted incrementally by 20 °C for each level to prevent explosions, and thus did not significantly affect the epoxide yield.

Polyols formation from in situ hydrolysis of optimized epoxidized oleic acid

Figure 4 shows the formation of polyols in the in situ hydrolysis of epoxidized palm oleic acid. The maximum RCO is 72% when titanium dioxide is applied as a catalyst. The high bio-polyol yield will affect bio-polyol production23. According to Dai et al. (2013)24, formic acid can reduce oxirane ring opening by inhibiting the deprotonation of performic acid.

The results align with previous studies, indicating that titanium dioxide enhances the reactivity of formic acid to form performic acid when reacted with hydrogen peroxide. Performic acid is generated through the reaction of formic acid with hydrogen peroxide. Subsequently, performic acid reacts with the double bonds of oleic acid by donating an oxygen atom to form an epoxy group25. Due to the inductive effect, shorter hydrocarbon chains push fewer electrons toward the carboxylic group, facilitating the release of protons (H+) and enhancing the formation of epoxide and bio-polyols. The textural properties of the titanium dioxide catalyst were characterised using Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) nitrogen adsorption–desorption analysis. The BET surface area was determined to be 26.40 m²/g, while the total pore volume was 0.1796 cm³/g. The average pore diameter, based on BJH desorption, was approximately 324.4 Å, indicating a mesoporous structure. These textural characteristics suggest sufficient surface accessibility and porosity for catalytic interaction during the reaction.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy

Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy was employed to identify the chemical characteristics of the samples, as illustrated in Fig. 5. FTIR analysis detected the emergence of long-chain hydrocarbon groups, hydroxyl (OH) groups, C = C double bonds in oleic acid, the oxirane ring in epoxidized oleic acid, and the oxirane ring-opening in polyol. The spectrum revealed the disappearance of the oleic acid double bond at 3000 cm¹, coinciding with the formation of epoxide groups. Functional groups corresponding to the oxirane ring opening (C-O-C) were observed at a wavenumber of 1363 cm⁻¹. Furthermore, polyol and alcohol (OH) groups were identified at wavenumbers of 1141 cm⁻¹ and 3556 cm⁻¹, respectively. The degradation of the oxirane ring at 1303 cm−1 led to the formation of polyol groups.

In addition, Shahdan et al. (2021)25 reported similar findings, highlighting that the transesterification of used cooking oil successfully produced polyols. The FTIR analysis in their study identified the OH group with a prominent peak at 3303.13 cm⁻¹. Consistent with these findings, the FTIR results in this study validate the production of polyols, demonstrating the reliability of the analytical approach for confirming the targeted functional groups.

Conclusion

In recent years, significant attention has been paid to epoxidized vegetable oils due to their renewable and sustainable nature, making them environmentally friendly. In the epoxidation process, performic acid was generated in situ to facilitate the production of epoxidised palm oleic acid, and hydrolysis was performed in situ for the formation of bio-polyols. The kinetic study demonstrates the successful modeling and optimization of the catalytic epoxidation process, providing valuable insights into the reaction’s dynamics and efficiency. The kinetic model effectively predicts the formation and consumption of key intermediates, with good alignment between experimental and simulated data during the initial phases of the reaction. The optimum process parameters for epoxidation were stirring speed (450 rpm), temperature (50 °C), formic acid molar ratio (1.5), and hydrogen peroxide molar ratio (1.5), resulting in a maximum RCO of 72%. This study’s significance lies in improving epoxidation and in situ hydrolysis by converting palm oleic acid into a value-added product (bio polyols).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

-

Alvear, M. et al. Epoxidation of light olefin mixtures with hydrogen peroxide on TS-1 in a laboratory-scale trickle bed reactor: transient experimental study and. Chem. Eng. Sci. 118467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ces.2023.118467 (2023).

-

Gunawan, E. R., Suhendra, D., Arimanda, P. & Asnawati, D. Murniati, epoxidation of terminalia Catappa L. Seed oil: optimization reaction. South. Afr. J. Chem. Eng. 43, 128–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sajce.2022.10.011 (2023).

-

Jalil, M. J. et al. Selective epoxidation of crude oleic acid-Palm oil with in situ generated performic acid. Int. J. Eng. Technology. 7 152–155. (2018).

-

De Souza, F. M., Sulaiman, M. R. & Gupta, R. K. Materials and Chemistry of Polyurethanes, ACS Symp. Ser. 1399 1–36. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1021/bk-2021-1399.ch001

-

Samarth, N. B. & Mahanwar, P. A. Modified vegetable oil based additives as a future polymeric Material — Review. Open J. Org. Polym. Mater. 1–22 (2015).

-

Azmi, I. S. et al. Synthesis of bio-polyol from epoxidized palm oleic acid by homogeneous catalyst. J. Elastomers Plast. 0, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/00952443221147029 (2022).

-

Marceneiro, S. et al. Eco-friendlier and sustainable natural-based additives for poly(vinyl chloride)-based composites. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 110, 248–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiec.2022.02.057 (2022).

-

Marriam, F., Irshad, A., Umer, I. & Arslan, M. Vegetable oils as bio-based precursors for epoxies. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 31, 100935. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scp.2022.100935 (2023).

-

Kaikade, D. S. & Sabnis, A. S. Polyurethane foams from vegetable oil-based polyols: a review. Polym. Bull. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00289-022-04155-9 (2022).

-

Janković, M. R., Govedarica, O. M. & Sinadinović-Fišer, S. V. The epoxidation of linseed oil with in situ formed peracetic acid: A model with included influence of the oil fatty acid composition. Ind. Crops Prod. 143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2019.111881 (2020).

-

Zhang, L., Zeng, Y. & Cheng, Z. Removal of heavy metal ions using Chitosan and modi Fi ed Chitosan: A review. J. Mol. Liq. 214, 175–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2015.12.013 (2016).

-

de Haro, J. C., Izarra, I., Rodríguez, J. F., Pérez, Á. & Carmona, M. Modelling the epoxidation reaction of grape seed oil by peracetic acid. J. Clean. Prod. 138, 70–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.05.015 (2016).

-

Kadir, M. Z. A., Azmi, I. S., Addli, M. A., Ahmad, M. A. & Jalil, M. J. In situ epoxidation of hybrid oleic acid derived from waste palm cooking oil and palm oil with applied ZSM-5 zeolite as catalyst. J. Polym. Environ. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10924-023-03101-8 (2024).

-

Jumain Jalil, M., Azfar Izzat Aziz, M., Nuruddin Azlan Raofuddin, D., Suhada Azmi, I. & Heiry Mohd Azmi, M. Saufi Md. Zaini, I. Mariah Ibrahim, Ring-Opening of epoxidized waste cooking oil by hydroxylation process: optimization and kinetic modelling. ChemistrySelect 7, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/slct.202202977 (2022).

-

Addli, M. A., Azmi, I. S. & Jalil, M. J. In situ epoxidation of castor oil via synergistic Sulfate-Impregnated ZSM-5 as catalyst. J. Polym. Environ. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10924-023-03056-w (2023).

-

Series, I. O. P. C. & Science, M. Catalytic efficiency of titanium dioxide (TiO 2) and zeolite ZSM-5 catalysts in the in-situ epoxidation of palm Olein catalytic efficiency of titanium dioxide (TiO 2) and zeolite ZSM-5 catalysts in the in-situ epoxidation of palm Olein, (2018). https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/358/1/012070

-

Sardari, A., Alvani, A. A. S. & Ghaffarian, S. R. Synthesis and characterization of novel castor oil-based polyol for potential applications in coatings. J. Renew. Mater. 7, 31–40. https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2019.00045 (2019).

-

Rasib, I. M., Jalil, M. J., Mubarak, N. M. & Azmi, I. S. Hybrid in-situ and ex-situ hydrolysis of catalytic epoxidation Neem oil via a peracid mechanism. Sci. Rep. 15, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84541-7 (2025).

-

Tuan Ismail, T. N. M. et al. Oligomeric composition of polyols from fatty acid Methyl ester: the effect of Ring-Opening reactants of epoxide Groups, JAOCS. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 95, 509–523. https://doi.org/10.1002/aocs.12044 (2018).

-

Arif, T., Tunku, Z., Zulkipli, M., Ab, B. & Azmi, I. S. Bio-lubricant production based on epoxidized oleic acid derived dated palm oil using in situ peracid mechanism. Inter. J. Chem. React. Eng. (2022).

-

Cozzi, D. et al. Organically functionalized titanium oxide / Na Fi on composite proton exchange membranes for fuel cells applications. J. Power Sources. 248, 1127–1132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpowsour.2013.10.070 (2014).

-

Aydoğmuş, E. & Kamişli, F. New commercial polyurethane synthesized with biopolyol obtained from Canola oil: Optimization, characterization, and thermophysical properties. J. Mol. Struct. 1256 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2022.132495 (2022).

-

Maia, D. L. H. & Fernandes, F. A. N. Influence of carboxylic acid in the production of epoxidized soybean oil by conventional and ultrasound-assisted methods. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-020-01130-0 (2020).

-

Dai, W., Li, J., Li, G., Yang, H. & Wang, L. Asymmetric epoxidation of alkenes catalyzed by a Porphyrin-Inspired manganese complex. Organ. Lett. 15292–15295. (2013).

-

Azmi, I. S. et al. Synthesis and kinetic model of oleic Acid-based epoxides by. Situ Peracid Mechanism. 71, 209–214 (2022).

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rahman, S.A., Azmi, I.S., Jalil, M.J. et al. Catalytic epoxidation of oleic acid through in situ hydrolysis for biopolyol formation. Sci Rep 15, 36986 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22123-x

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22123-x