Introduction

The most natural areas typically host a variety of plant species that serve as nutritional centers and natural pharmacies with primary (nutrients) and secondary (pharmaceutical) compounds. Bioactive substances of plant origin (polyphenols) may benefit ruminants by fighting gastrointestinal parasites and bacteria and improving nutrition or reproduction1. Plants produce various plant secondary metabolites, such as phenols, alkaloids and terpenes, which are responsible for their therapeutic effect, diversity, synergy and combinations that can contribute to different pharmacological efficacies. Self-medication of grazing ruminants on meadow pastures containing mixed plant species responds to the general demand to reduce the use of synthetic chemicals in agriculture and promote organic farming systems2,3. However, grazing ruminants are at constant risk of getting infected by larvae of parasitic gastrointestinal nematodes (GINs). In small ruminants, GIN diseases are mainly caused by the parasite Haemonchus contortus, whose adults live attached to the wall of the abomasum and feed on the host’s blood. The control of GINs is usually limited to the repeated use of anthelmintics in conjunction with grazing management strategies4. However, the development of GINs in the host abomasum also causes pathology with mucosal damage and gastropathy with protein loss, followed by host inflammatory immune responses5,6. A search for suitable natural alternatives to chemotherapeutic agents that could be used for the control and therapy of GINs is therefore needed. Many studies of medicinal perennial plants or natural products against GINs have been published in the last decade7,8. Chicory (Cichorium intybus) is a woody, perennial herbaceous plant of the family Asteraceae, and phytochemical screening of chicory confirmed the presence of tannins, saponins and flavonoids9,10. Chicory is also considered a quality forage with high contents of some trace minerals (e.g. Mg and Zn) that can also improve the rate of growth of grazing animals11,12. The ruminal microbiome is responsible for the nutritional and metabolic needs of ruminants, so it can be influenced by several host factors such as age, breed, disease, infection and feed13,14. Changes in nutrient composition can also alter the composition of the ruminal microbiota and its enzymatic activity15. Therefore, analyses of ruminal microbial fermentation and morphological observations of rumen are needed to identify possible consequences of bioactive compounds used in the diet of parasite-laden lambs.

The diversity and synergy of bioactive compounds and various combinations in medicinal plants used in our previous treatments contributed to some pharmacological efficacy against H. contortus infection16,17,18,19. These treatments can also influence antioxidant parameters in the abomasal mucosa and help trigger a local immune response in tissues20. Finally, we observed that even the replacement of meadow hay with sainfoin pellets could directly affect the dynamics of infection and the composition of ruminal methanogenic bacteria after 14 days of supplementation to infected lambs21,22. Based on these previous studies with medicinal plants in lambs, we hypothesized that grazing different plant species, especially chicory, would alter not only the dynamics of infection but also ruminal microbial fermentation properties and histology. Our goal was to determine whether meadow pasture with a mixed species diversity of plants and/or enriched with experimentally sown chicory could favorably affect growth parameters and the ruminal environment of lambs with endoparasites.

Results

Growth parameters of the lambs

All lambs used in the experiment had similar initial body weights (BWs, Table 1). BW differed on the days (D) D89 (P = 0.029), D131 (P = 0.050) and D144 (P = 0.027) and reached higher values in the chicory (CHIC) group (28.2, 33.0, and 38.2 kg) than in the control (CON) group (24.5, 29.1, and 32.7 kg). Live weight gains (LWGs) were higher in the CHIC group (5.10 and 5.16 kg) than in the CON group (2.28 and 3.56 kg) on D89 (P = 0.004) and D144 (P = 0.017). Daily weight gain (DWG) was higher in the CHIC group (P < 0.001; 163.8 kg) than in the CON group (131.0 kg).

Ruminal fermentation characteristics

The concentration of ammonia N was higher in the CHIC group (P = 0.007; 234 mg/L) than in the CON group (170 mg/L) (Table 2). The molar proportions of propionate (P = 0.016) and n-caproate (P = 0.049) were higher in the CON group (14.4 and 0.08 mol%) than in the CHIC group (11.7 and 0.031 mol%). Other fermentation parameters did not differ significantly between the groups (P > 0.05). The specific enzymatic activities of amylase (P = 0.008) and xylanase (P = 0.049) were significantly higher in the CHIC group (1.85 and 73.6 µcat/g protein) than in the CON group (0.94 and 54.2 µcat/g protein), but the activity of CM-cellulase was unaffected (P > 0.05). The total protozoan population did not differ significantly between the groups (P = 0.167).

Ruminal bacterial population

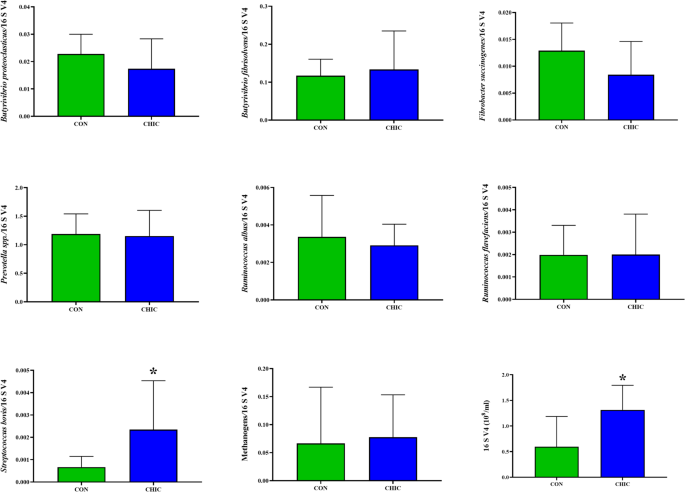

Total bacterial populations and the relative abundances of Streptococcus bovis were significantly higher (P < 0.05) in the CHIC group than in the CON group (Fig. 1). The other microbial populations, such as those of Butyrivibrio proteoclasticus, B. fibrisolvens, Fibrobacter succinogenes, Prevotella spp., Ruminococcus albus, R. flavefaciens and methanogens did not differ significantly (P > 0.05) among the groups.

Effect of the control and experimental groups on the relative abundance of the 16 S rRNA gene (expressed relative to the total abundance of bacterial genes) of the ruminal bacterial population for Butyrivibrio proteoclasticus, B. fibrisolvens, Fibrobacter succinogenes, Prevotella spp., Ruminococcus albus, R. flavefaciens, Streptococcus bovis and total methanogens. Data are described as specific gene copy numbers per 16 S rRNA gene copy number ± SD (*P < 0.05).

Ruminal histology

The homogeneity of the papillae was affected in both the CON and CHIC groups. The lamina propria was inflamed in the CON group in 75% of cases and the CHIC group in 50% of cases, and the epithelia were inflamed in both groups in 25% of cases. Connective-tissue edema was present in the majority of lambs from the CON and CHIC groups, but hyperemia was present only in the CHIC group in 12.5% of cases. The epithelium of the CON group was moderately wide, with a thick layer of desquamation and balloon-shaped keratinocytes and organisms with Balantidium coli morphology were present (Fig. 2a). Hydropic degeneration of epithelial cells, hyperkeratosis, lymphocytic aggregates, connective-tissue edema and protozoa were present in the CON group (Fig. 2b and c). There were balloon-shaped keratinocytes under the rough layer, connective-tissue edema, and inflammation in the lamina propria of the epithelium in the CHIC group (Fig. 3a). The loss of ruminal papillae architecture due to massive neutrophilic inflammation with parakeratosis and the ballooning of keratinocytes in the CHIC group is shown in Fig. 3b. Connective-tissue edema, infiltration of inflammatory cells, hyperemia and extravasation in the CHIC group are shown in Fig. 3c.

Histological changes to the ruminal tissue in the Control group. (a) Sections stained with H&E (100×) showing ruminal papillae with the desquamation and ballooning of keratinocytes and organisms with Balantidium coli morphology. (b) Sections stained with H&E (100×) showing the hydropic degeneration of epithelial cells, hyperkeratosis, lymphocytic aggregates, connective-tissue edema and protozoa. (c) Sections stained with H&E (200×) showing the greater magnification of the previously marked area in (b).

Histological changes to the ruminal tissue in the Chicory group. (a) Sections stained with H&E (40×) showing balloon-shaped keratinocytes under the rough layer, connective-tissue edema, and inflammation in the lamina propria of the epithelium and protozoa. (b) Sections stained with H&E (40×) showing the loss of ruminal papillary architecture due to massive neutrophilic inflammation with parakeratosis and the ballooning of keratinocytes. (c) Sections stained with H&E (100×) showing connective-tissue edema, infiltration of inflammatory cells, hyperemia and extravasation.

Discussion

Infection caused by GINs can have a strong negative impact on the productivity of sheep flocks associated with reduced rates of growth or body weights4. Our previous results indicated that BW or LWG may16 or may not be affected by GIN infection23, consistent with the majority of studies in the meta-analysis reporting a negative effect of parasitism on growth and production. These effects, however, were significant in only 58.3% of the studies24. Our results indicated that before D62 post-infection, BWG and LWG were comparable in both groups of lambs, which was consistent with the majority of our trials with medicinal plants against GINs in the diets of infected lambs conducted indoors17,19,25. In the present experiment, the lambs grazing on pasture were probably able to seek out plants with certain medicinal, antioxidant or immunological effects and could also increase the consumption of plants containing secondary compounds with antiparasitic effects as self-medication against GINs3,26. A possible loss of appetite in subclinically infected ruminants can lead to a decrease in growth performance (BW and LWG)27,28,29. Furthermore, some byproducts of infection may likely affect the taste of infected animals3,26. However, the growth of the lambs in the CHIC group increased significantly after D89 post-infection and growth performance expressed as DWG was significantly higher (131.0 vs. 163.8 g/day, Table 1). The meadow grasslands enriched with experimentally sown chicory were likely more beneficial for improving lamb growth30 than the meadow grassland in the control plot.

This finding was in contrast to previous results31, which reported no effect of including chicory in the diets of grazing beef bulls on their performance compared to beef bulls grazing on ryegrass. Moreover, the levels of phytochemicals on both pastures (Tables 3 and 4) were higher in May and July compared to September, along with a lower diversity of analyzed phytochemicals in September. Better growth results were nevertheless achieved in the CHIC group. Some plants, e.g., Artemisia absinthium32, or the herbal mix composed of plant parts from Solanum xanthocarpum, Hedychium spicatum, Curcuma longa, Piper longum and Ocimum sanctum33 improve feed consumption due to their bioactive compounds and can also possibly increase the rate of growth of lambs. On the other hand, chicory phytochemicals have properties that improve the welfare of animals with endoparasites9,34. Therefore, the significant results for growth performance in the CHIC group during the last 55 days of the experiment were not surprising, and the differences in BW and LWG of the grazing lambs between the CHIC and CON groups in favor of the CHIC group confirm the value of feeding chicory35. The self-medication of grazing lambs improved the nutrition and well-being of the animals, but the meadow pastures with experimentally sown chicory increased the efficiency of nutrient use and improved the production indicators of the infected lambs. Infected grazing lambs could choose the medicinal plant themselves while having a variety of nutritional alternatives available to them.

The concentrations of ruminal ammonia-N and microbial protein were not only affected by the intake of dietary protein and energy but also by microbial metabolism. The concentration of ruminal ammonia-N in the present study was higher in the CHIC group than in the CON group. However, the concentration of ammonia-N in the rumen can influence the degradation of fiber, so each feed has an optimal ammonia concentration36, which increases immediately after feeding for 2 to 3 h and decreases until the next feeding37. The capacity of protein synthesis and the use of ammonia-N in our experiment depended on the rate of carbohydrate fermentation, and presumably, greater fermentation in the CHIC group determined higher feed efficiency and allowed for elevated ammonia-N levels. Therefore, the higher ammonia-N concentrations in this study were attributed to the lower neutral-detergent fiber and acidic-detergent fiber contents (Table 2) in the pasture with chicory compared to the control pasture38. In general, if energy and ammonia-N concentrations are not synchronized in the rumen, ammonia-N concentrations are not constant in the rumen39,40. According to the literature, the optimal level of ammonia-N in the rumen varies (50 − 80 mg/L41, 50 − 190 mg/L42, or 60 − 290 mg/L43 and depends on the optimal ammonia-N concentration for the maximal rate of fermentation44 and the maximal production of microbial proteins41,42. Feed intake and nutrient supply in the CON and CHIC lambs depended mainly on the rate of fermentation, and the ammonia-N concentration was probably optimal for the maximum rate of digestion. Chicory can modulate ruminal fermentation to reduce ammonia-N concentration45. The lower ammonia-N concentrations in the CON group compared to the CHIC group could also be due to higher ammonia-N uptake by ruminal microorganisms or to lower proteolytic activity in the rumen, but the concentrations were consistent with the content of crude protein of the feed substrates from the control and experimental plots (Table 5).

The ruminal functions of lambs are usually altered in response to H. contortus infection, and infected sheep have lower ruminal propionate concentrations46. On the other hand, a mixed infection with H. contortus and Trichostrongylus colubriformis in sheep shifted short-chain fatty acids (SCFA) production toward the propionate proportion46. However, the molar proportion of propionate in the CON group was similar to that in our previous experiment with lambs on medicinal herbals, but without H. contortus infection47. The higher propionate concentration in the CON group compared to the CHIC group in this experiment could indicate that more energy and nutrition were available to support the growth in the CON group when the SCFAs were absorbed and converted to nutrients in the rumen48. However, only the propionate concentration was higher in the CON group, which could also indicate that propionate formation competed with methanogenesis for metabolic hydrogen in the rumen49. Although the relative abundances of methanogens did not differ significantly between groups (Fig. 1), the ruminal microbiota likely promoted propionate formation in the CON group and partially inhibited methanogenesis to mitigate methane emissions50.

In addition to increasing the abundance of bacterial genera associated with methanogenesis, GIN infection can also increase the abundance of other bacterial genera involved in microbial homeostasis51. Bioactive plant compounds from Acacia mearnsii can also modulate the microbiome in the rumens of lambs with GIN infections (e.g. affect bacterial counts and N metabolism)52, which is consistent with our results. Thus, the ruminal microbiome could have been affected by higher ammonia-N concentrations in the GIN-infected lambs, affecting microorganisms and the genes controlling metabolic pathways involved in microbial homeostasis, and by bioactive compounds present in the pastures. On the other hand, no effects on nutrient metabolism and methane emissions were detected during the relatively short 36-day experiment in sheep53, despite the significant effects of GIN infection on animal health. The lambs in the CHIC group may have adapted to chicory grazing with an increased shift in the relative abundances of total ruminal bacteria and amylolytic bacteria (S. bovis). This shift was also accompanied by the increased specific activity of α-amylase, which is usually associated with the particulate fraction54. However, protein metabolism during GIN infection is affected more by infection than fiber metabolism55. Therefore, GIN infection probably increased carbohydrate metabolism in the rumen based on higher α-amylase activity in the CHIC group, compensating for the loss of the supply of energy from depressed protein and lipid metabolism caused by infection29. The ruminal microbiota of the CHIC group was probably more abundant than the CON group, also associated with xylanase activities, which accelerate the biodegradation of xylan into SCFAs and gases during the ruminal processing of lignocellulosic biomass56. However, some bacterial phylotypes can also contribute to differences in feed efficiency and host productivity and can, or need not, depend on the diet57.

The ruminal papillae in almost all lambs of both groups were long or moderately long and thin, with mechanical degradation of papillary homogeneity. SCFAs, as products of ruminal fermentation and especially butyrate, stimulate the development of ruminal papillae and induce morphofunctional changes58,59. SCFAs in the rumen are absorbed through the ruminal epithelium, and the rate of absorption is primarily influenced by their concentration, the surface area of the papillae in the rumen and the availability of transport proteins60,61. Fermentation was greater in the CHIC group, which determined the higher feed efficiency, even though the molar proportion of butyrate was not affected in our experiment. Evidence supports a more active gastrointestinal tract associated with improved feed efficiency and genes associated with feed efficiency, supporting relationships between metabolic activity and ruminal epithelial function and structure62. However, almost all lambs had thin epithelia at D144 post-infection, indicating lower metabolic and functional activity in the papillary epithelium63.

Thus, the growth and development of the ruminal papillae probably depended mainly on the type of feed consumed, and their development was stimulated by the final products of ruminal fermentation and by the composition of the pasture. However, the connective-tissue edema, inflammation of the lamina propria with infiltrates of inflammatory cells, especially lymphocytes, and the presence of singular organisms with the morphology of B. coli were detected in all lambs of both groups. The damage was probably caused by dystrophic epithelial changes that led to cellular degeneration and the infiltration of leukocytes. These lesions may affect absorptive capacity and stimulate inflammation and secondary infection of the rumen by the resident microbial population64, which was consistent with our results.

Conclusion

Beneficial feeding values of the chicory were confirmed, because its polyphenols altered microbial populations and hydrolase activities, minimizing the loss of feed energy. Finally, including experimentally sown chicory in the pasture may increase the total concentration of ammonia-N in the rumen, benefiting microbial protein synthesis and nutrient use in grazing lambs with endoparasites. The ability of the host ruminal epithelial cells to transport short-chain fatty acids was unaffected in the lambs of both groups, regardless of the active fermentation in the rumen, which affected the health of the papillae and ruminal epithelium.

Methods

Control and experimental plots

The experiment was carried out on pastures on a private farm (PETLAMB) in Petrovce, district of Prešov, Slovakia. Two plots with an area of 0.43 ha of meadow grassland with a mixed species of plants were selected and fenced with electric fencing. The plots were equipped with an automatic water trough and a shelter. The control plot consisted exclusively of meadow grassland with plants from different families, which were identified based on the atlas of plants65, i.e. Astrantia major, A. carniolica, Daucus carota, Achillea millefolium, A. nobilis, Centaurea nigrescens, Cichorium intybus, Cirsium oleraceum, C. vulgare, Crepis sancta, Erigeron annuus, Hypochaeris glabra, Chamaemelum nobile, Solidago nemoralis, Tussilago farfara, Lepidium draba, Campanula patula, Knautia arvensis, Calystegia sepium, Carex hirta, Dryopteris filix-mas, Equisetum sylvaticum, Trifolium pratense, T. repens, Vicia hirsuta, V. sepium, Centaurium erythraea, Geranium maculatum, G. pratense, Hypericum perforatum, Clinopodium vulgare, Galeopsis pubescens, Mentha longifolia, Prunella vulgaris, Stachys officinalis, S. palustris, Thymus pulegioides, Lythrum salicaria, Plantago lanceolata, P. major, Veronica spicata, Agrostis capillaris, Calamagrostis arundinacea, C. epigejos, Setaria pumila, Lysimachia vulgaris, Alchemilla xanthochlora, Filipendula ulmaria, F. vulgaris, Fragaria vesca, Prunus domestica, Rosa canina, Rubus ursinus and Urtica dioica. The main polyphenolic compounds in the mixture of plants from the control plot (Pasture I—harvested May-July and Pasture II—harvested September) are shown in Table 3. The peak numbers in chromatograms represent the list of the main phytochemicals as numbered in Supplementary Tables S1 and S2. 25% of the second plot was used for reclamation with chicory. The chicory mixture contained 81.5% chicory (Cichorium intybus), 14.8% sainfoin (Onobrychis viciifolia) and 3.7% alfalfa (Medicago sativa). The main polyphenolic compounds in the chicory plot collected from May to July and from the last collection in September are shown in Table 4. The peak numbers in chromatograms represent the list of the main phytochemicals as numbered in Supplementary Table S3. The land on these plots had never been grazed by animals and was therefore considered virtually worm-free. The plots were established in the spring, and the experiment was conducted between May and October. The experiment was part of a larger study that investigated natural chemotherapeutic alternatives for controlling haemonchosis in lambs and had been described in more detail previously26.

Animals, diets and experimental design

Sixteen male and female (1:1) Tsigai breed lambs aged 3–4 months with an average weight of 13.6 ± 0.52 kg from a sheep farm (PD Ružín–farm Ružín, Kysak, Slovakia) were dewormed with the recommended dose of albendazole (Albendavet 1.9% susp. a.u.v, DIVASA-FARMAVIC S.A., Barcelona, Spain) during a 7-day (D) period of adaptation before the start of the experiment. Each animal was fed 300 g dry matter (DM) Mikrop ČOJ, a commercial concentrate (MIKROP, Čebín, Czech Republic). The animals were randomly divided into two groups of eight lambs each (n = 8/group) based on their live weights and genders: control animals grazing on the control plot (CON) and animals grazing on the experimental plot (CHIC). The number of animals used in the experiment was assigned following VICH GL13 guidelines proposed by the European Medicines Agency. All parasite-free lambs were orally infected with approximately 5000 third-stage larvae of the MHCo1 strain of H. contortus susceptible to anthelmintics. The CHIC group started to graze the chicory-enriched pasture on D34 post-infection when the infection peaked. Fecal samples were collected rectally on D21, D34, D48, D62, D76, D89, D103, D118, D131 and D144 post-infection, and the number of eggs per gram (EPG) of feces was quantified. A modified McMaster technique66 with a sensitivity of 50 EPG was used for detecting H. contortus eggs. All lambs were positive, with the highest mean EPGs of 12 800 ± 4293 in the CON group and 19 750 ± 8744 in the CHIC group on D34 post-infection26. The lambs were weighed on D7, D34, D62, D89, D131 and D144. BW, LWG and DWG were examined during the experiment. The experimental period was 144 d from May to October, and the lambs were euthanized following the rules of the European Commission67. The carcasses were sent to the Department of Pathological Anatomy and Pathological Physiology, University of Veterinary Medicine and Pharmacy in Košice in the Slovak Republic. The rumens were taken from each lamb in each group immediately after slaughter in the abattoir and transported to the laboratory.

Ethics statement

We confirm that all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. The study was conducted following the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and national legislation in the Slovak Republic (G.R. 377/2012; Law 39/2007) for the care and use of research animals. The experimental protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Institute of Parasitology of the Slovak Academy of Sciences on January 20, 2023 (protocol code 14/2023). All sheep were euthanized using an overdose of 140 mg/kg pentobarbital (Dolethal, Vetoquinol, Ltd., Towcester, UK) at the end of the experiment at the abattoir (abattoir of the Centre of Biosciences of SAS, Institute of Animal Physiology, Košice, Slovakia, No. SK U 03023). The pentobarbital overdose had a negligible effect on the estimated parameters in the lambs. The study is reported following ARRIVE guidelines.

Measurements and chemical analysis

Samples from an area of 0.2 × 0.2 m were collected from 10 random quadrats in the control and chicory pastures from May to September. These samples and commercial concentrate were analyzed in triplicate by standard procedures68,69. The chemical compositions of the feed are given in Table 5.

Analysis of polyphenols by UPLC-QTOF-MS

The polyphenols were analysed as was previously described26. DataAnalysis 4.3 software (Bruker Daltonics GmbH, Bremen, Germany) provided a ranking according to the best fit of measured and theoretical isotopic patterns within a specific mass accuracy window. The quality of the isotopic fit was expressed by the mSigma-value. From Smart Formula 3D matched peaks were sent to the MetFrag website in silico fragmentation for computer-assisted identification of metabolite mass spectra. Additionally, a few databases were used to search for the structural identity of the metabolites supported with appropriate literature information70,71, the human metabolome database (http://www.hmdb.ca/), the BiGG database (http://bigg.ucsd.edu/), the PubChem database (http://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), the MassBank database (http://www.massbank.jp), KEGG (www.genome.jp) and the Metlin database (http://metlin.scripps.edu). The amount of the particular compounds (phenolic acids, flavonoids and anthocyanidins) in the extracts were calculated as equivalents of chlorogenic acid (CAS 327-97-9, 3-Caffeoylquinic acid) at 320 nm UV, isoquercetin (CAS 482-35-9, Quercetin 3-o-glucopyranoside) at 254 nm UV and cyanidin chloride (CAS 528-58-5) at 520 nm. Stock solutions of chlorogenic acid, isoquercetin and cyanidin were prepared in MeOH at concentrations of 3.2, 4.5 and 1 mg/mL respectively, and were kept frozen until analysis. Calibration curves for these three compounds were constructed based on seven concentration points. After data acquisition, raw UPLC-QTOF-MS spectra (negative mode) were pre-processed using ProfileAnalysis software (version 2.1, Bruker Daltonik GmbH, Germany).

Ruminal fermentation, microbial analysis and histology

The pH values were measured using a pH meter (InoLab pH Level 1, Weilheim, Germany). A liquid sample (4 mL) was collected for the subsequent analysis of ammonia N. The concentration of ammonia N was determined in the ruminal fluid by the phenol-hypochlorite method72. The SCFAs were analyzed by gas chromatography, as previously described16. Specific enzymatic activities of the ruminal microorganisms were determined by the preparation of a cell-free homogenate as described23. Samples for microbial analyses were isolated using a PureLink Microbiome DNA Purification Kit Invitrogen (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The concentration of DNA was measured using Nanodrop 1 C (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, USA). Quantitative PCR was performed on a Roche Light Cycler 480 II (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) using standard curves for the absolute quantification of specific taxa and total bacteria by amplification of the 16 S subunit gene. The primers used were listed previously73. Data are presented as the copy number of specific amplicons per total bacteria in the sample. Data are described as specific gene copy numbers per 16 S rRNA gene copy number ± SD. Samples for counting ciliate protozoa were fixed in equal volumes of 8% formaldehyde, and the protozoa were counted and identified microscopically as previously described74. Histological examinations were performed similarly to those previously described47.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using an unpaired t-test (GraphPad Prism 9.2.0 (332) 2021; GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, USA). Results were considered significant at P < 0.05.

Data availability

The data sets used and/or analyzed are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

-

Villalba, J. J., Costes-Thiré, M. & Ginane, C. Phytochemicals in animal health: diet selection and trade-offs between costs and benefits. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 76, 113–121. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0029665116000719 (2017).

-

Ronchi, B. & Nardone, A. Contribution of organic farming to increase sustainability of mediterranean small ruminants livestock systems. Livest. Prod. Sci. 80, 17–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0301-6226(02)00316-0 (2003).

-

Villalba, J.J., Miller, J., Ungar, E. D., Landau, S. Y. & Glendinning, J. Ruminant self-medication against Gastrointestinal nematodes: evidence, mechanism, and origins. Parasite 21, 31. https://doi.org/10.1051/parasite/2014032 (2014).

-

Sutherland, I. & Scott, I. Gastrointestinal Nematodes of Sheep and Cattle: Biology and Control 1–242 (Wiley-Blackwell, 2010).

-

Stear, M. J., Bishop, S. C., Henderson, N. G. & Scott, I. A key mechanism of pathogenesis in sheep infected with the nematode Teladorsagia circumcincta. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 4, 45–52. https://doi.org/10.1079/ahrr200351 (2003).

-

Batťányi, D. et al. Antibody response and abomasal histopathology of lambs with haemonchosis during supplementation with medicinal plants and organic selenium. Vet. Anim. Sci. 19, 100290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vas.2023.100290 (2023).

-

Garcia-Bustos, J. F., Sleebs, B. E. & Gasser, R. B. An appraisal of natural products active against parasitic nematodes of animals. Parasit. Vectors. 12, 306. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-019-3537-1 (2019).

-

Bosco, A. et al. Use of perennial plants in the fight against Gastrointestinal nematodes of sheep. Front. Parasitol. 2, 1186149. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpara.2023.1186149 (2023).

-

Street, R. A., Sidana, J. & Prinsloo, G. Cichorium intybus: traditional uses, phytochemistry, pharmacology, and toxicology. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat Med. 2013, 579319. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/579319 (2013).

-

Peña-Espinoza, M. et al. Antiparasitic activity of Chicory (Cichorium intybus) and its natural bioactive compounds in livestock: A review. Parasit. Vectors. 11, 475. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-018-3012-4 (2018).

-

Barry, T. N. The feeding value of Chicory (Cichorium intybus) for ruminant livestock. J. Agric. Sci. 131, 251–257. https://doi.org/10.1017/S002185969800584X (1998).

-

Abbas, Z. K. et al. Phytochemical, antioxidant and mineral composition of hydroalcoholic extract of Chicory (Cichorium intybus L.) leaves. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 22, 322–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjbs.2014.11.015 (2015).

-

Mizrahi, I., Jami, E. & Review The compositional variation of the rumen Microbiome and its effect on host performance and methane emission. Animal 12, 220–232. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1751731118001957 (2018).

-

Clemmons, B. A., Voy, B. H. & Myer, P. R. Altering the gut Microbiome of cattle: considerations of host-microbiome interactions for persistent Microbiome manipulation. Microb. Ecol. 77, 523–536. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-018-1234-9 (2019).

-

Gruninger, R. J., Ribeiro, G. O., Cameron, A. & McAllister, T. A. Invited review: application of meta-omics to understand the dynamic nature of the rumen Microbiome and how it responds to diet in ruminants. Animal 13, 1843–1854. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1751731119000752 (2019).

-

Váradyová, Z. et al. The impact of a mixture of medicinal herbs on ruminal fermentation, parasitological status and hematological parameters of the lambs experimentally infected with Haemonchus contortus. Small Rumin Res. 151, 124–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smallrumres.2017.04.023 (2017).

-

Váradyová, Z. et al. Effects of herbal nutraceuticals and/or zinc against Haemonchus contortus in lambs experimentally infected. BMC Vet. Res. 14, 78. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-018-1405-4 (2018).

-

Mravčáková, D. et al. Natural chemotherapeutic alternatives for controlling of haemonchosis in sheep. BMC Vet. Res. 15, 302. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-019-2050-2 (2019).

-

Mravčáková, D. et al. Anthelmintic activity of Wormwood (Artemisia absinthium L.) and Mallow (Malva sylvestris L.) against Haemonchus contortus in sheep. Animals 10, 219. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10020219 (2020).

-

Mravčáková, D. et al. Effect of Artemisia absinthium and Malva sylvestris on antioxidant parameters and abomasal histopathology in lambs experimentally infected with Haemonchus contortus. Animals 11, 462. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11020462 (2021).

-

Petrič, D. et al. Effect of Sainfoin (Onobrychis viciifolia) pellets on rumen Microbiome and histopathology in lambs exposed to Gastrointestinal nematodes. Agriculture 12, 301. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12020301 (2022).

-

Komáromyová, M. et al. Impact of Sainfoin (Onobrychis viciifolia) pellets on parasitological status, antibody responses, and antioxidant parameters in lambs infected with Haemonchus contortus. Pathogens 11, 301. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens11030301 (2022).

-

Mikulová, K. et al. Growth performance and ruminal fermentation in lambs with endoparasites and in vitro effect of medicinal plants. Agriculture 13, 1826. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture13091826 (2023).

-

Mavrot, F., Hertzberg, H. & Torgerson, P. Effect of gastro-intestinal nematode infection on sheep performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Parasit. Vectors. 8, 557. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-015-1164-z (2015).

-

Komáromyová, M. et al. Effects of medicinal plants and organic selenium against ovine haemonchosis. Animals 11, 1319. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11051319 (2021).

-

Komáromyová, M. et al. Insights into the role of bioactive plants for lambs infected with Haemonchus contortus parasite. Front. Vet. Sci. 12, 1566720. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2025.1566720 (2025).

-

Sykes, A. R. & Coop, R. L. Intake and utilization of food by growing sheep with abomasal damage caused by daily dosing with Ostertagia circumcincta larvae. J. Agric. Sci. 88, 671–677. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021859600037369 (1977).

-

Coop, R. L., Sykes, A. R. & Angus, K. W. The effect of three levels of intake of Ostertagia circumcincta larvae on growth rate, food intake and body composition of growing lambs. J. Agric. Sci. 98, 247–255. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021859600041782 (1982).

-

Xiang, H., Fang, Y., Tan, Z. & Zhong, R. Haemonchus contortus infection alters Gastrointestinal microbial community composition, protein digestion and amino acid allocations in lambs. Front. Microbiol. 12, 797746. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2021.797746 (2022).

-

Campbell, B. J., McCutcheon, J. S., Marsh, A. E., Fluharty, F. L. & Parker, A. J. Delayed weaning improves the growth of lambs grazing Chicory (Cichorium intybus) pastures. Small Rumin Res. 204, 106517. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smallrumres.2021.106517 (2021).

-

Marley, C. L. et al. Effects of chicory/perennial ryegrass Swards compared with perennial ryegrass Swards on the performance and carcass quality of grazing beef steers. PLoS ONE. 9, e86259. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0086259 (2014).

-

Beigh, Y. A., Mir, D. M., Ganai, A. M., Ahmad, H. A. & Muzamil, S. Body biometrics correlation studies on sheep fed Wormwood (Artemisia absinthium L.) herb supplemented complete diets. Indian J. Vet. Res. 28, 8–13. https://doi.org/10.5958/0974-0171.2019.00002.5 (2019).

-

Orzuna-Orzuna, J. F. et al. Growth performance, carcass characteristics, and blood metabolites of lambs supplemented with a polyherbal mixture. Animals 11, 955. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11040955 (2021).

-

Nwafor, I. C., Shale, K. & Achilonu, M. C. Chemical composition and nutritive benefits of Chicory (Cichorium intybus) as an ideal complementary and/or alternative livestock feed supplement. Sci. World J. 2017, 7343928. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/7343928 (2017).

-

Niderkorn, V. et al. Effect of increasing the proportion of Chicory in forage-based diets on intake and digestion by sheep. Animal 13, 718–726. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1751731118002185 (2019).

-

Alipour, D. et al. Effect of combinations of feed-grade Urea and slow-release Urea in a finishing beef diet on fermentation in an artificial rumen system. Transl Anim. Sci. 4, txaa013. https://doi.org/10.1093/tas/txaa013 (2020).

-

Chumpawadee, S., Sommart, K., Vongpralub, T. & Pattarajinda, V. Effects of synchronizing the rate of dietary energy and nitrogen release on ruminal fermentation, microbial protein synthesis, blood Urea nitrogen and nutrient digestibility in beef cattle. Asian-Aust J. Anim. Sci. 19, 181–188. https://doi.org/10.5713/ajas.2006.181 (2006).

-

Hassan, M. U. et al. Effect of multispecies Swards on ruminal fermentation, methane emission and potential for climate care cattle farming- an in vitro study. Animal 19, 101386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.animal.2024.101386 (2025).

-

Henning, P. H., Steyn, D. G. & Meissner, H. H. Effect of synchronization of energy and nitrogen supply on ruminal characteristics and microbial growth. J. Anim. Sci. 71, 2516–2528. https://doi.org/10.2527/1993.7192516x (1993).

-

Ribeiro, S. S., Vasconcelos, J. T., Moraism, M. G., Ítavo, C. B. C. F. & Franco, G. L. Effects of ruminal infusion of a slow-release polymer-coated Urea or conventional Urea on apparent nutrient digestibility, in situ degradability, and rumen parameters in cattle fed low-quality hay. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 164, 53–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2010.12.003 (2011).

-

Satter, L. D. & Slyter, L. L. Effect of ammonia concentration on rumen microbial protein production in vitro. Br. J. Nutr. 32, 199–208. https://doi.org/10.1079/BJN19740073 (1974).

-

Miller, E. L. Evaluation of foods as sources of nitrogen and amino acids. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 32, 79–84. https://doi.org/10.1079/PNS19730019 (1973).

-

Pisulewski, P. M., Okorie, A. U., Buttery, P. J., Haresign, W. & Lewis, D. Ammonia concentration and protein synthesis in the rumen. J. Sci. Food Agric. 32, 759–766. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.2740320803 (1981).

-

Mehrez, A. Z., Orskov, E. R. & McDonald, I. Rates of rumen fermentation in relation to ammonia concentration. Br. J. Nutr. 38, 437–443. https://doi.org/10.1079/bjn19770108 (1977).

-

Minneé, E. M. K., Waghorn, G. C., Lee, J. M. & Clark, C. E. F. Including Chicory or plantain in a perennial ryegrass/white clover-based diet of dairy cattle in late lactation: feed intake, milk production and rumen digestion. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 227, 52–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2017.03.008 (2017).

-

Doyle, E. K., Kahn, L. P. & McClure, S. J. Rumen function and digestion of Merino sheep divergently selected for genetic difference in resistance to Haemonchus contortus. Vet. Parasitol. 179, 130–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.01.063 (2011).

-

Petrič, D. et al. Impact of zinc and/or herbal mixture on ruminal fermentation, microbiota, and histopathology in lambs. Front. Vet. Sci. 8, 630971. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2021.630971 (2021).

-

Orskov, E. R. & Ryle, M. Energy Nutrition in Ruminants 1–149 (eds Orskov, E. R.) (Elsevier Applied Science, 1990).

-

Wang, K., Xiong, B. & Zhao, X. Could propionate formation be used to reduce enteric methane emission in ruminants? Sci. Total Environ. 855, 158867. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.158867 (2023).

-

Ungerfeld, E. M. Metabolic hydrogen flows in rumen fermentation: principles and possibilities of interventions. Front. Microbiol. 11, 589. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.00589 (2020).

-

Corrêa, P. S. et al. The effect of Haemonchus contortus and Trichostrongylus colubriforms infection on the ruminal Microbiome of lambs. Exp. Parasitol. 231, 108175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exppara.2021.108175 (2021).

-

Corrêa, P. S. et al. Tannin supplementation modulates the composition and function of ruminal Microbiome in lambs infected with Gastrointestinal nematodes. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 96, fiaa024. https://doi.org/10.1093/femsec/fiaa024 (2020).

-

Mwangi, P. M. et al. Impact of Haemonchus contortus infection on feed intake, digestion, live weight gain, and enteric methane emission from red Maasai and Dorper sheep. Front. Anim. Sci. 4, 1212194. https://doi.org/10.3389/fanim.2023.1212194 (2023).

-

Raffrenato, E., Badenhorst, M. J., Shipandeni, M. N. T. & van Zyl, W. H. Rumen fluid handling affects measurements of its enzymatic activity and in vitro digestibility. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 280, 115060. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2021.115060 (2021).

-

Houdijk, J. G. M., Kyriazakis, I., Kidane, A. & Athanasiadou, S. Manipulating small ruminant parasite epidemiology through the combination of nutritional strategies. Vet. Parasitol. 186, 38–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.11.044 (2012).

-

Takizawa, S. et al. Shifts in Xylanases and the microbial community associated with Xylan biodegradation during treatment with rumen fluid. Microb. Biotechnol. 15, 1729–1743. https://doi.org/10.1111/1751-7915.13988 (2022).

-

Hernandez-Sanabria, E. et al. Impact of feed efficiency and diet on adaptive variations in the bacterial community in the rumen fluid of cattle. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 1203–1214. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.05114-11 (2012).

-

Gäbel, G., Vogler, S. & Martens, H. Short-chain fatty acids and CO2 as regulators of Na + and Cl – absorption in isolated sheep rumen mucosa. J. Comp. Physiol. B. 161, 419–426. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00260803 (1991).

-

Mentschel, J., Leiser, R., Mülling, C., Pfarrer, C. & Claus, R. Butyric acid stimulates rumen mucosa development in the calf mainly by a reduction of apoptosis. Arch. Tierernahr. 55, 85–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450390109386185 (2001).

-

Bannink, A. et al. Modeling the implications of feeding strategy on rumen fermentation and functioning of the rumen wall. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 143, 3–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2007.05.002 (2008).

-

Melo, L. Q. et al. Rumen morphometrics and the effect of digesta pH and volume on volatile fatty acid absorption. J. Anim. Sci. 91, 1775–1783. https://doi.org/10.2527/jas.2011-4999 (2013).

-

Kern, R. J. et al. Rumen papillae morphology of beef steers relative to gain and feed intake and the association of volatile fatty acids with Kallikrein gene expression. Livest. Sci. 187, 24–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.livsci.2016.02.007 (2016).

-

Tamate, H. & Fell, B. F. Cell deletion as a factor in the regulation of rumen epithelial populations. Vet. Res. Commun. 1, 359–364. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02267667 (1977).

-

Martín Martel, S. et al. Pathological changes of the rumen in small ruminants associated with indigestible foreign objects. Ruminants 1, 118–126. https://doi.org/10.3390/ruminants1020009 (2021).

-

Bellmann, H. Great Plant Atlas (Ikar, 2009).

-

Coles, G. C. et al. World association for the advancement of veterinary parasitology (W.A.A.V.P.) methods for the detection of anthelmintic resistance in nematodes of veterinary importance. Vet. Parasitol. 44, 35–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4017(92)90141-u (1992).

-

European Commission (EC). Council Regulation (EC) 1099/2009 of 24 September 2009 on the Protection of Animals at the Time of Killing.

-

Horwitz, W. Official Methods of AOAC International (Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC), 2000).

-

Van Soest, P. J., Robertson, J. B. & Lewis, B. A. Methods for dietary fiber neutral detergent fiber, and non-starch polysaccharides in relation to animal nutrition. J. Dairy. Sci. 74, 3583–3597. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(91)78551-2 (1991).

-

Carazzone, C., Mascherpa, D., Gazzani, G. & Papetti, A. Identification of phenolic constituents in red Chicory salads (Cichorium intybus) by high-performance liquid chromatography with diode array detection and electrospray ionisation tandem mass spectrometry. Food Chem. 138, 1062–1071. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.11.060 (2013).

-

Tardugno, R., Pozzebon, M., Beggio, M., Del Turco, P. & Pojana, G. Polyphenolic profile of Cichorium intybus L. endemic varieties from the Veneto region of Italy. Food Chem. 266, 175–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.05.085 (2018).

-

Broderick, G. A. & Kang, J. H. Automated simultaneous determination of ammonia and total amino acids in ruminal fluid and in vitro media. J. Dairy. Sci. 63, 64–75. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(80)82888-8 (1980).

-

Petrič, D. et al. Efficacy of zinc nanoparticle supplementation on ruminal environment in lambs. BMC Vet. Res. 20, 425. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-024-04281-8 (2024).

-

Williams, A. G. & Coleman, G. S. The Rumen Protozoa 1–425 (Springer, 1992).

Acknowledgements

We highly appreciate the cooperation of technical laboratories and technical assistance within the project of the Scientific Grant Agency of the Ministry of Education of the Slovak Republic, the Slovak Academy of Sciences (VEGA 2/0007/25) and the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine and Animal Sciences, Poznań University in Poland, and the Department of Animal Nutrition, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine and Animal Sciences, Poznań University in Poland (No. 506.533.04.00). We also thank Polish Minister of Science and Higher Education within the framework of the Strategy of the University of Poznań for 2024-2026 in the field of improving the quality of scientific research and development work in priority research areas. The English has been revised throughout the whole manuscript by a native English language editor, Dr. William Blackhall (https://www.globalbiologicalediting.com/index.html).

Funding

This study was supported by funds from the EU NextGenerationEU of the Recovery and Resilience Plan for Slovakia under project No. 09I03-03-V04-00200/2024/VA. The funders had no role in designing the study, collecting, analyzing, or interpreting the data, or writing the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Petrič, D., Leško, M., Demčáková, K. et al. Chicory modulates the rumen environment in lambs with endoparasites. Sci Rep 15, 35455 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19409-5

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19409-5