Main

Genome editing technologies, including those derived from prokaryotic CRISPR–Cas systems, have revolutionized life science research and are poised to transform medicine and agriculture. Single-protein CRISPR–Cas effectors, including the widely adopted Cas9 nuclease from Streptococcus pyogenes (SpCas9), have been used in biotechnology owing to their simplicity, robustness and compact form. To diversify the CRISPR toolbox and expand editing capabilities, new systems have been mined across diverse microbial and viral genomes. Although these systems have been sought for specific properties, such as small size or extended protein stability in biofluids3,4, they typically exhibit tradeoffs in critical attributes such as basal activity in target cells, protospacer-adjacent motif (PAM) selectivity, thermal optima or in vitro biochemical properties, ultimately limiting their reach4,5,6,7.

Repurposed CRISPR systems have been optimized for biotechnology using a range of protein engineering approaches, including directed evolution and structure-guided mutagenesis. Directed evolution of CRISPR–Cas proteins has proven extremely powerful yet can be limited by the rugged and non-convex nature of the fitness landscapes8,9,10,11, along with the difficulty of implementing selection-based screening in human cells. Structure-guided rational mutagenesis offers an alternative or synergistic approach that has proven successful for improving Cas9 basal activity and specificity in human cells12,13,14,15. Similar results may be achievable with structure-conditioned protein sequence design models16,17. However, both of these approaches depend on explicit structural hypotheses, either in the form of mechanistic understanding for rational mutagenesis or structures representing key functional states for computational design, which are difficult to obtain for functions more complex than simple binding interactions.

Protein language models eschew explicit structural hypotheses and instead learn the co-evolutionary blueprint underlying protein function18. When pretrained on large sets of diverse protein sequences, language models (LMs) learn to represent structure and function without supervision2,19. Subsequent fine-tuning of these models yields family-specific specialists that generate new proteins adhering to the functional constraints of their family yet diverging substantially in sequence space. This approach has been validated through the design of functional lysozymes20 and demonstrated in silico across several families21. Related work has also shown that co-evolutionary models22,23,24 of individual protein families can be used to design new, highly active sequences23. Compared to protein LMs, these family-specific models are less computationally expensive to train but are typically restricted to pairwise coupling terms (limiting their expressiveness) and do not leverage sequences from other protein families. Despite the considerable utility of such sequence-based approaches, it remains to be seen how well either strategy performs for protein families with several complex functions, such as CRISPR–Cas effectors.

In this work, we demonstrate that LMs can effectively generate diverse CRISPR–Cas proteins spanning a broad set of families. Moreover, we demonstrate that generated type II effector proteins can assemble as functional gene editors in human cells, despite being hundreds of mutations away from any known natural protein. We perform extensive characterization of one exemplar editor, which we denote OpenCRISPR-1, and show that it is highly functional and specific.

LMs generate diverse CRISPR–Cas proteins

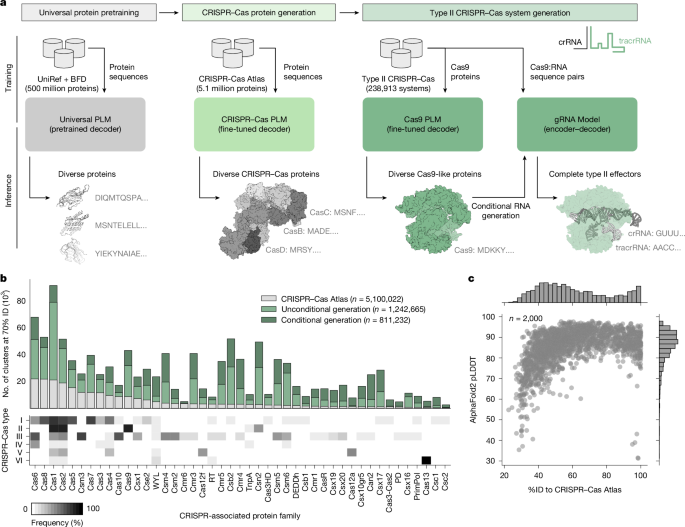

Generative protein LMs are typically pretrained on large datasets of natural protein sequences spanning diverse phylogenies and functions2. These models are capable of generating realistic protein sequences that reflect the distribution and properties of natural proteins25. However, for specific applications, such as the generation of gene editors, it is necessary to steer generation towards particular subsets of protein families of interest (Fig. 1a).

a, Overview of the language-modelling approach to design CRISPR–Cas systems. LMs learn the general constraints of protein evolution through pretraining on diverse proteins spanning the evolutionary tree and then are specialized for design by fine-tuning on Cas protein and nucleic acid data. b, Expansion of the sequence diversity for 45 Cas protein families, measured by the number of clusters (at 70% sequence identity (70%ID)) for natural proteins and clusters from generated sequences. Stacked bars are coloured by the source of the sequences making up their clusters (CRISPR–Cas Atlas, recovered from CRISPR–Cas mining; generated Cas, 4 million generated proteins from this study). Heatmap indicates the natural distribution of each protein family across different types of CRISPR–Cas systems. c, AlphaFold2 was used to predict structures for 2,000 randomly selected generated proteins. The scatterplot shows the distribution of mean pLDDT and the %ID to natural proteins from the CRISPR–Cas Atlas.

To this end, we performed exhaustive data mining to construct a dataset of curated CRISPR operons, including Cas proteins, CRISPR arrays, trans-activating CRISPR RNAs (tracrRNAs) and PAMs (Extended Data Fig. 1). We refer to this resource as the CRISPR–Cas Atlas. Using a custom pipeline, we searched 26.2 terabases of assembled microbial genomes and metagenomes, spanning diverse phyla and biomes, to uncover 1,246,088 CRISPR–Cas operons, including more than 389,000 single-effector systems classified as type II, type V or type VI. Our resource displayed expanded natural diversity compared to curated databases such as CRISPRCasDB and CasPDB (Extended Data Fig. 1e), as well as UniProt, the world’s largest protein resource. Across all Cas families, the CRISPR–Cas Atlas has on average 2.7× more protein clusters than UniProt using a 70% sequence identity (%ID) clustering threshold and even greater expansions for families such as Cas9 (4.1×), Cas12a (6.7×) and Cas13 (7.1×).

To generate new CRISPR–Cas proteins, we fine-tuned the ProGen2-base LM2 on the CRISPR–Cas Atlas, balancing for protein family representation and sequence cluster size (Fig. 1a). From this model, we generated 4 million sequences; half were generated directly from the model (unconditional), whereas the other half were prompted with up to 50 residues from the N or C terminus of a natural protein to guide generation towards a particular family (conditional). After strict filtering and sequence clustering (Supplementary Fig. 1), we found that the generated sequences represented a 4.8-fold expansion of diversity compared to natural proteins from the CRISPR–Cas Atlas (Fig. 1b). For families with few natural proteins, such as Cas13 and Cas12a, generated sequences represent an 8.4- and 6.2-fold increase in diversity, respectively. Among the sequences guided towards a particular family, we typically observed near-perfect adherence to the family of interest with 50 or fewer residues provided, indicating that generation is steerable with minimal context. Given the conservative nature of the filters applied to the generated sequences, we expect that the reported increases in diversity represent a lower bound; however, as the generated sequences diverge further from natural examples, detecting realistic proteins becomes more difficult.

We next evaluated the rate of new cluster generation by the model with respect to the number of sequences sampled. For each family, we counted the number of distinct clusters in subsets ranging from one sequence to the full set (Supplementary Fig. 2). In general, the rate of new cluster generation for generated sequences significantly outpaced that of natural sequences. Among the generated sequences for each family that survived filtering, the identity to the nearest natural protein was typically between 40% and 60% (Fig. 1c). To investigate the novelty of these generated sequences, we calculated the cumulative sequence identity explained by increasing numbers of natural proteins (Extended Data Fig. 2). Compared to natural CRISPR–Cas proteins, the generated sequences displayed similar levels of chimerism, indicating that LMs produce sequences with novelty akin to that of evolution. Despite considerable deviation in sequence space, the generated proteins were confidently predicted by AlphaFold2, with 81.65% of structures having a mean predicted local-distance difference test (pLDDT) above 80—although AlphaFold2 is known to fold non-functional proteins with high confidence as well26. For a small number of sequences, we observed high similarity to natural proteins in the CRISPR–Cas Atlas but low structure prediction confidence, owing to limited homology in the ColabFold sequence database used for predictions. (Fig. 1c). Finally, we investigated the structural composition of the generated sequences and found that many were predicted to adopt folds highly similar to natural proteins from the same family (Extended Data Fig. 3), indicating they may be functional.

LMs generate diverse type II effectors

Although many CRISPR–Cas proteins have been leveraged for genome editing27,28, Cas9 remains the most widely used. To generate new Cas9-like sequences, we prompted the CRISPR–Cas model with 50 residues from the N or C terminus of Cas9s sampled from the CRISPR–Cas Atlas. However, only 27.6% of these prompted generations survived our strict sequence viability filters. To more efficiently and accurately generate viable Cas9-like sequences, we fine-tuned another LM using only the 238,913 Cas9 sequences from the CRISPR–Cas Atlas (Fig. 1a and Extended Data Fig. 1). This model produced viable Cas9-like sequences at twice the rate of the CRISPR–Cas model (54.2%; Supplementary Fig. 3a) and did not require any prompting.

To explore the latent sequence distribution of type II effectors, we used the Cas9 model to generate 1 million Cas9 proteins. The resulting viable generations (n = 542,042) were clustered together with natural Cas9s at 40%ID and used as input to construct a maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree (Fig. 2a). The resulting landscape was dominated by generated proteins, which made up 94.1% of the total phylogenetic diversity (as measured by cumulative branch length) and resulted in a 10.3-fold increase in diversity relative to the entire CRISPR–Cas Atlas (Fig. 2b). New phylogenetic groups were distributed across the tree, indicating that the model has captured the known natural diversity of Cas9 and is not overfitting to any particular lineage. Generated sequences diverged from the CRISPR–Cas Atlas, with an average identity of only 56.8% to any natural sequence (Fig. 2c). Further, we found that the generated proteins displayed cumulative identity trends similar to natural Cas9s (Extended Data Fig. 4), indicating that the chimeric novelty produced by the LM was similar in form to what would be expected from discovery of new natural Cas9s. Although the number of generated proteins is large, the number of new clusters does not seem to have saturated (Supplementary Fig. 3b), indicating that many more Cas9-like proteins could be generated. Next, we analysed the phylogenetic distribution of Cas9 orthologues that have been biochemically characterized7 or used as genome editors29. We observed considerable diversity of generated proteins in the vicinity of these characterized orthologues, indicating that the model is capable of generating proteins with a variety of functional properties.

a, Phylogenetic tree of natural and generated proteins clustered at 40%ID (n = 15,340 cluster representatives). Biochemically characterized Cas9s from ref. 7 are labelled, and Cas9 proteins used as genome editors are shown in bold29. Lineages are coloured black if they contain any natural protein or green if they are exclusively represented by generated proteins. b, Pie chart indicates the percent of phylogenetic diversity represented by natural or generated proteins. Phylogenetic diversity was calculated as the cumulative branch length of subtrees represented by a given set of sequences. c, Distribution of the identity of generated Cas9 to the nearest protein in the CRISPR–Cas Atlas. d, Comparison of protein length between natural and generated proteins in the same 50%ID clusters. e, Fraction of generated and natural Cas9 proteins containing key functional domains according to structural searches with Foldseek against SCOPe families. In total, 79.2% and 48.2% of natural and generated proteins were functionally complete, respectively. f, Predicted structure for new Cas9-like protein selected from a 30%ID cluster with 423 members composed entirely of generated sequences. Despite high sequence novelty (39.2%ID to CRISPR–Cas Atlas), the predicted structure bears structural resemblance to Nme1Cas9 (Protein Data Bank ID 6JE9, template modelling score (TM-score) = 0.72). g, Naturally occurring and generated crRNAs and tracrRNAs were obtained for a set of ten effector proteins. h, sgRNAs were formed from RNA components and embedded into a two-dimensional space by t-distributed stochastic neighbour embedding32 according to the pairwise edit distances. Each point represents an sgRNA sequence, with colours corresponding to source protein. Tree scale bar, 1.0.

To further assess the viability of the generated proteins, we compared the sequence lengths of generated and natural sequences (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. 3c). Overall, generated sequences closely matched the length of natural proteins from the same protein cluster, with a Pearson correlation of 0.97 (Fig. 2d). To assess the structural viability of generated Cas9-like proteins, we used AlphaFold2 (ref. 30) to predict the structures of 5,000 generated and 5,000 natural sequences, with one sequence each being selected randomly from the largest 70%ID protein clusters among each group. Most structures were predicted confidently (with 99.4% having mean pLDDT above 80), including for Cas9-like proteins with as low as 60%ID to any natural protein (Extended Data Fig. 5a), and showed significant overlap with experimentally determined structures from the Protein Data Bank (Extended Data Fig. 5b). By aligning the structures against curated families from the SCOPe database31, we confirmed the presence of core Cas9 domains in most generated proteins and at a similar rate as naturals (Fig. 2e). This included the HNH and RuvC nuclease domains (100% and 52.1%, respectively), which are responsible for DNA cleavage, as well as the PAM-interacting domain (PID; 92.9%) and target recognition (REC) lobe (99.9%) (Fig. 2e). Although RuvC is a conserved and essential Cas9 domain, its detection may be underestimated because of difficulty in identifying its short, split subdomains. This structural and functional completeness extended to even the most divergent proteins, including a subset that belonged to 30%ID clusters composed entirely of generated proteins. One such protein had a predicted structure resembling Nme1Cas9 (template modelling score 0.71) despite sharing only 25.8%ID to Nme1Cas9 and a maximum of 39.2%ID to any protein in the CRISPR–Cas Atlas (Fig. 2f).

Type II systems are also dependent on a guide RNA (gRNA) that is required for target recognition and cleavage. The gRNA is composed of a targeting RNA sequence (spacer), CRISPR RNA (crRNA) repeat and tracrRNA. The tracrRNA and crRNA components are typically derived from natural systems, and the spacer sequence is programmed to match the target DNA site for gene editing applications. From the CRISPR–Cas Atlas, we collected 112,212 type II effector proteins for which we could confidently identify, orient and align the corresponding crRNA and tracrRNA sequences. These data were used to train a sequence-to-sequence gRNA model that conditionally generates crRNA and tracrRNA sequences for a given protein (Fig. 1a). As an initial validation of the gRNA model, we designed ten gRNAs for a set of effector proteins previously used as genome editors (Fig. 2g). Each of the designed gRNAs, as well as the natural gRNAs from metagenome mining, were formatted into single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) and embedded according to their pairwise edit distances with t-distributed stochastic neighbour embedding32. We observed that the model-designed sgRNAs were most similar to the naturally derived sgRNAs for each protein (Fig. 2h). As further validation, we found crRNA:tracrRNA pairs often formed the canonical duplex (Supplementary Fig. 4) and that the model could accurately predict the compatibility of sgRNAs between diverse Cas9 orthologues (Extended Data Fig. 6). Together, these results indicate that the model can be used to generate functional sgRNAs for generated Cas9-like proteins.

Designed editors function in human cells

To generate Cas9-like proteins for experimental characterization, we used a constrained generation strategy wherein we prompted the LM fine-tuned on Cas9 proteins using either the N-terminal segment or the C-terminal PID of SpCas9 (Supplementary Fig. 5). In doing so, we reasoned that the generated sequences would maintain compatibility with both the PAM and sgRNA preferences of SpCas9, facilitating direct comparison of protein activity across the same genomic targets with the same sgRNA. In total, we generated 200,000 and 150,000 Cas9-like proteins prompted by the N-terminal segments and C-terminal PIDs, respectively. From this set, we selected 82 SpCas9 PID-conditioned sequences and 127 fully generated sequences, created by combining our generated N-terminal segments and PID domains, on the basis of an average of pretrained and Cas9-fine-tuned LM log likelihoods and auxiliary predictors of compatibility with SpCas9’s PAM and tracrRNA. In total, we selected 209 Cas9-like proteins for subsequent functional analysis in human cells (Fig. 3a).

a, Phylogenetic tree of natural Cas9 proteins, ancestral reconstructions and generated effector proteins near SpCas9. Annotations surrounding the tree indicate selection criteria used to identify 48 generated proteins for further characterization. b, Editing efficiency (indel rate relative to SpCas9) of 209 generated proteins across three target sites: HEK3 (i), HEK2 (ii) and CD3G_1 (iii). Sequences are ordered according to relative indel rates, with the number of sequences showing activity and surpassing SpCas9 indicated on the x axis. c, Mutational Levenshtein distances from the nearest natural protein in the CRISPR–Cas Atlas and SpCas9 for 131 generated proteins with observed editing activity. The Levenshtein distance is the minimal number of edits between two sequences, including substitutions, insertions and deletions. d, On- and off-target editing efficiency for SpCas9 and 48 generated proteins. Points correspond to on- or off-target editing at five sites (AAVs1, FANCF, HEK2, HEK3, VEGFA; with three off targets per site). Bars reflect the median of all on- and off-target editing. e, On- and off-target editing efficiency for natural Cas9s, high-fidelity variants, chimeric sequences, consensus designs, ancestral reconstructions (rec.), HMM emissions, arDCA designs, LigandMPNN designs and generated proteins from this work. Each point represents the average on- or off-target editing at five sites (with three off targets per site) for a single protein. f, Genome-wide off-target analysis using SITE-Seq, measured at four enzyme concentrations. Points represent the percentage of total cleavage events for each guide that occurred at on-target sites. Bars represent the median across sites. Tree scale bar, 1.0.

We next set out to explore whether our Cas9-like proteins were able to mediate genome editing in human cells. We tested 209 sequences by cotransfecting HEK293T cells with nuclease plasmids and SpCas9 sgRNA plasmids, targeting one of three previously characterized target sites and inferred DNA repair outcomes after three days using a Sanger-sequencing-based method33. Across all three sites, we observed a wide range of editing efficiencies, with a subset of Cas9-like proteins showing activity on par with or higher than SpCas9 (Fig. 3b). In contrast with the edit distance to SpCas9, LM scores were highly predictive of enzyme activity, separating active and inactive enzymes at the HEK3 target site with an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve value of 0.83 (Supplementary Fig. 6). Among the set of active nucleases, we observed significant sequence deviation from SpCas9 and the nearest natural proteins in the CRISPR–Cas Atlas (Fig. 3c).

For further characterization, we next selected 48 Cas9-like proteins that were fully generated (both N- and C-terminal domains), displayed moderate or high insertion and deletion (indel) rates across one or more sites and were substantially different from any natural or engineered enzyme in patent databases (lens.org) (Fig. 3a). This set comprised five distinct clusters at 90%ID, with each protein sharing 77.5–87.1%ID to the nearest natural Cas9. In each cluster, the generated proteins were between one and 40 mutations from any other (median seven mutations). We assayed the editing efficiency and specificity of these 48 proteins across a panel of previously characterized SpCas9 on- and off-target sites (n = 5 and n = 15, respectively)34,35 alongside SpCas9. Nuclease- and sgRNA-expressing plasmids were cotransfected in HEK293T cells, and DNA repair outcomes were measured after three days using next-generation sequencing of amplicons (NGS). We observed both high editing efficiency and specificity with many of our generated nucleases (Fig. 3d), with some even outperforming SpCas9.

To contextualize the performance of our language-modelling strategy for designing Cas9-like proteins, we also tested a set of natural and designed proteins with similar levels of sequence novelty with respect to SpCas9 (Supplementary Fig. 7). Natural sequences (ten total) with between 57%ID and 71%ID to SpCas9 between were identified from the CRISPR–Cas Atlas and UniRef100. For alternative design approaches, we considered sequences from evolutionary methods (14 total from consensus sequence design, hidden Markov model (HMM) emission36 and arDCA24) and structure-based methods (five from LigandMPNN17; Supplementary Fig. 8). Finally, we included nine sequences from the literature, including four high-fidelity SpCas9 variants37 and five SpCas9 ancestral reconstructions38. To facilitate testing at common NGG PAM target sites, we replaced the PID of all comparison sequences with that of SpCas9 except literature-reported variants, which already target NGG PAMs. These 43 sequences were tested alongside five generated proteins at the same set of on- and off-target sites as the broader panel of generated proteins (Fig. 3e and Extended Data Fig. 7). For natural proteins, we observed a range of activity levels, with most being considerably less active than SpCas9. One natural protein, Streptococcus uberis Cas9, displayed high on-target activity and reduced off targets at these sites, reflecting the practical utility of mining natural sequence diversity to uncover highly functional nucleases. Among the evolutionary-based design strategies, we observed a general trend towards lower success rates as methods became more expressive. The most highly active sequences came from consensus design, followed by ancestral reconstruction and chimeric design, whereas sequences from HMM emission and arDCA were largely inactive. Our language-modelling-based strategy stands in contrast to this trend, yielding many highly active proteins despite being less conservative than methods like consensus design. Finally, for the structure-based designs from LigandMPNN, we observed no activity, probably owing to the method’s dependence on static structures and lack of evolutionary constraints on the complex requisite functions of Cas9 proteins.

Our top hit, PF-CAS-182, displayed levels of activity comparable to SpCas9 at on-target sites (median indel rates of 56.4% versus 47.1%) while having a 95% reduction in editing at known SpCas9 off-target sites (median indel rates of 0.32% versus 6.1%). Based on its compelling performance, we nominated PF-CAS-182 as the OpenCRISPR-1 protein. To obtain an unbiased estimate of genome-wide off-target activity, we purified OpenCRISPR-1 and SpCas9 proteins and used these as input to SITE-Seq using the same five gRNA used in Fig. 3e (AAVs1, HEK2, HEK3, FANCF and VEGFA) at four different ribonucleoprotein concentrations. Consistent with our initial cell-based analysis, we observed that a substantially higher proportion of cleavage events occurred at on-target sites for OpenCRISPR-1 compared to SpCas9 across all ribonucleoprotein concentrations and gRNAs tested (Fig. 3f). Importantly, the OpenCRISPR-1 off targets were a subset of the SpyCas9 off targets (Extended Data Fig. 8), strongly indicating that OpenCRISPR-1 does not generate new cleavage patterns. OpenCRISPR-1 did not share any mutations with eight previously engineered high-fidelity Cas9 variants37, indicating that this enzyme achieves a low off-target profile by means of a distinct set of molecular interactions.

OpenCRISPR-1 lacked previously identified immunodominant and subdominant SpCas9 T cell epitopes for HLA-A*02:01, indicating that it may be less immunogenic than SpCas939 (Supplementary Fig. 9). To test this hypothesis, we performed an iELISA to measure the amount of human antibody bound to OpenCRISPR-1 and two other generated proteins (PF-CAS-151 and PF-CAS-189) (Extended Data Fig. 9). Plates were coated with 1 µg ml−1 protein concentrations, and serum samples from 40 healthy donors were diluted from 100-fold to 1,600-fold. iELISA quantification showed lower immunogenicity for all generated Cas9-like proteins compared to SpCas9 at one or more dilution levels. These results indicate that proteins designed with machine learning have the potential to be less immunogenic than pathogen-derived genome editors such as SpCas9.

OpenCRISPR-1 was 1,380 residues in length and considerably diverged from both SpCas9 (403 mutations) and any natural protein in the CRISPR–Cas Atlas (182 mutations). Alignment to NCBI-nr showed top hits to proteins from several Streptococcus spp. (Streptococcus cristatus, S. pyogenes and Streptococcus sanguinis), but none exceeding a sequence identity of 86.3%. Taken together, these three natural Cas9s yielded a cumulative identity of 98.3% for OpenCRISPR-1, in line with what would be expected for a protein with 80–90%ID to the nearest natural (Supplementary Fig. 10). Template-based AlphaFold2 (ref. 30) predictions of the catalytic state40 of OpenCRISPR-1 illustrated that most of the mutations were concentrated at the solvent-exposed surface of the protein, with only a fraction located at the protein–nucleic acid interface (Extended Data Fig. 10a,b). Most critical nucleic-acid-coordinating residues and nuclease-site components were preserved, demonstrating the capability of the model to accurately constrain all necessary catalytic and interaction sites (Supplementary Table 1). In addition to point mutations, OpenCRISPR-1 contained two loop insertions in the REC1 and HNH domains. The function of these inserts remains unknown; however, the nine-residue positively charged insertion in the REC1 domain may interact with the phosphate backbone of both the repeat:anti-repeat segment of the gRNA and the PAM-proximal region of the target DNA (Extended Data Fig. 10c). This insertion is analogous to sequence graftings of positively charged loops between natural Cas9 orthologues to boost activity41. The four-residue insertion in the HNH domain is compatible with all the experimentally elucidated catalytic states40 and may have a role in stabilizing the cleavage checkpoint state (Extended Data Fig. 10d).

To more thoroughly characterize OpenCRISPR-1, we used a cell-based assay with NGS measurement of indel rates to screen 98 previously characterized SpCas9 target sites harbouring either NGG or non-NGG PAMs15,42 (Supplementary Table 3). After quality control, we were able to characterize nuclease performance at 92 of these sites (NGG PAMs, n = 49; non-NGG PAMs n = 43). Our measurements of activity for SpCas9 at these targets were moderately below reported levels15, probably owing to the transfection efficiency observed from lipofection (Supplementary Fig. 11). In agreement with our previous experiment, OpenCRISPR-1 displayed comparable levels of on-target activity across sites bearing the NGG PAM (Fig. 4a,b) and resulted in a similar distribution of DNA repair outcomes (Supplementary Fig. 12). Interestingly, OpenCRISPR-1 exhibited several-fold reduction in activity at genomic sites bearing a mismatch in the PAM (two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum P value = 0.0005) (Fig. 4c). These results indicate that OpenCRISPR-1 has activity comparable to SpCas9 at on-target sites while avoiding double-strand breaks at sites with mismatches in either the PAM or target regions.

a,b, On-target editing efficiency (indel formation) of OpenCRISPR-1 (OC-1) protein at NGG (n = 49) and non-NGG PAMs (n = 43) (a). OpenCRISPR-1 exhibits comparable activity at targets with an NGG PAM but lower editing at sites lacking an NGG PAM (b). c, Relative activity of SpCas9 to OpenCRISPR-1 across sites with different PAMs (NGG, n = 49; NGC, n = 11; NGT, n = 10; NGA, n = 10; NAG, n = 9; NTG, n = 2; NCG, n = 1). d, Adenine base editors were created by attaching deaminase domains to the N terminus of OpenCRISPR-1 and SpCas9 nickase variants (D10A mutation for both proteins). e, Adenine base editing efficiency (A-to-G) at three target sites: HEK2 (i), T39 (ii), CD3G_1 (iii). ABE8.20 is a highly active deaminase from directed evolution, whereas PF-DEAM-1 and PF-DEAM-2 were generated from LMs. Across all target sites and with distinct deaminases, OpenCRISPR-1 nickase shows compatibility with base editing. f, Editing efficiency at HEK3 target site with designed sgRNAs (green) and SpCas9’s sgRNA (grey). Four of five generated proteins displayed increased editing efficiency with design sgRNAs. g, Change in editing efficiency compared to SpCas9’s sgRNA. The majority of designed sgRNAs yield performance that is not significantly different from SpCas9’s guide, whereas a subset either significantly improves or worsens editing efficiency (t-test P value < 0.05).

Next, we investigated whether OpenCRISPR-1 could be used in a base editing system. Base editors have emerged as powerful systems for modifying single nucleotides in the genome without the complications of generating double-strand breaks. We converted OpenCRISPR-1 to a putative target-strand nickase (containing D10A mutation) and fused it to a previously engineered adenosine deaminase (ABE8.20) commonly used in base editing43 (Fig. 4d). We tested for editing in HEK293T cells using plasmid delivery, with sgRNAs targeting three genomic loci containing adenines in the editing window (that is, position 3–9 in the spacer). We observed robust A-to-G conversion with the OpenCRISPR-1 base editor on all three target sites (35–60% editing rate), which was comparable to an ABE8.20 base editor system using SpCas9 nickase (Fig. 4e) and without resulting in indel formation (Supplementary Fig. 13).

We next set out to engineer a fully synthetic base editor system, including the deaminase domain. Towards this goal, we trained models based on TadA-like proteins from UniProtKB44 and BFD30 and generated a series of synthetic adenine deaminases with 55–80%ID to any known natural deaminase, including both engineered variants and the Escherichia coli TadA from which these variants were evolved43,45. Initial screening experiments with SpCas9 nickase showed that a subset of generated deaminases were active at several targets in the human genome (Supplementary Fig. 14). We then tested two of our most active deaminases (PF-DEAM-1 and PF-DEAM-2) fused to the N terminus of either SpCas9 or OpenCRISPR-1 nickases. Our generated deaminases showed A-to-G editing levels comparable to ABE8.20 with both nickase scaffolds while producing minimal bystander edits (Supplementary Fig. 15). Similarly narrow editing windows were observed in early adenine base editors evolved from ecTadA through directed evolution45 but were eventually traded for overall activity in later rounds of selection43.

Although all of the experiments up to this point had used the SpCas9 sgRNA scaffold, we reasoned that this might not be optimal for OpenCRISPR-1 and other generated Cas9-like proteins, which contained hundreds of mutations that could potentially disrupt RNA interactions. Using the gRNA model described previously, we designed 14 generated sgRNAs for each of five generated Cas9-like proteins (including OpenCRISPR-1) and tested for editing in HEK293T cells at one target site (HEK3). Generated sgRNA sequences exhibited high sequence conservation compared to SpCas9’s sgRNA (Supplementary Fig. 16), with most mutations occurring in flexible regions of the secondary structure (for example, loops or linker regions). Overall, we observed enhanced editing with 31 designed sgRNAs relative to SpCas9’s sgRNA (Fig. 4f), including significant improvements for four sgRNAs for two of five variants (Fig. 4g). To confirm these findings, we conducted a similar editing experiment using two generated proteins at two more sites, again finding comparable editing with most designed sgRNAs and a small number yielding statistically significant improvements to editing (Supplementary Fig. 17g,h). Designed sgRNAs were generally compatible with SpCas9, but only one showed significant improvements in editing efficiency (Supplementary Fig. 17d–f). We found that OpenCRISPR-1, which had shown consistently high editing efficiency in previous experiments, performed similarly with a designed sgRNA or SpCas9’s sgRNA. These results indicate that this generated protein may be applicable either as part of a fully generated gene editor or as a drop-in replacement for SpCas9 in existing editing systems.

Discussion

Gene editing technologies adapted from natural prokaryotic antiviral systems have enabled precise, programmable manipulation of genetic material across research, therapeutic and industrial applications. Although evolution has created a massive diversity of CRISPR–Cas proteins, identifying the best natural protein for a given application (if it exists) remains a principal bottleneck in the design of more advanced gene editing systems. Generative LMs for DNA46 or proteins2 offer an alternative paradigm wherein models learn from natural diversity and can be steered towards the most promising regions of sequence space. This approach allows us to diversify existing lineages of interest or explore regions of sequence space that were not visited by evolution. In this work, we focused on generating type II effectors in the phylogenetic neighbourhood of SpCas9, ultimately yielding the OpenCRISPR-1 editing system. Our results indicate that OpenCRISPR-1 may provide a viable alternative to SpCas9 for use in gene editing technologies, with similar editing behaviour and compatibility with systems like base editing. In the future, it will be important to examine OpenCRISPR-1 activity across a range of experimental conditions, cell types and delivery methods to more thoroughly characterize robustness11,37,47.

As part of this work, we curated the CRISPR–Cas Atlas—a large resource of CRISPR systems. Datasets like the CRISPR–Cas Atlas are critical for refining the general learnings of pretrained protein LMs into a functional blueprint for design. Although we focused primarily on type II effector proteins, our exploratory results indicate that effectors from other Class 2 systems (for example, Cas12a, Cas12f and Cas13) may be amenable to the same approach. In some cases, these alternative systems have unique properties that would benefit gene editing applications (for example, reduced size of Cas12f or RNA interference of Cas13). Aside from fine-tuning protein LMs for generation, we envision that the CRISPR–Cas Atlas could be used to model specific properties of gene editors, such as nuclease size, PAM preference, tracrRNA compatibility, thermostability or temperature-dependent activity. For instance, a model to predict PAM preference could enable efficient engineering of target- or allele-specific editors. The capability of generative LMs to produce diverse, highly functional nuclease proteins, as demonstrated in this work, provides a foundation from which to pursue these fit-for-purpose editors.

Computational protein design has advanced considerably in recent years with the development of increasingly sophisticated deep learning algorithms. These improvements have been achieved through integration of more powerful tools into design pipelines that have remained largely unchanged48. Specifically, the design of protein function typically begins with an explicit structural hypothesis that is translated into a set of constraints to guide a search for satisfying sequences49. This approach has largely reduced some design problems, such as de novo design of protein binders50, to practice. However, for the design of complex functions as embodied by the gene editors in this work, structure-based approaches do not offer a straightforward solution. By contrast, LMs provide an implicit means of modelling protein function (and thus structure) through sequence alone18.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The CRISPR–Cas Atlas and associated code are available at GitHub (https://github.com/Profluent-AI/CRISPR-Cas-Atlas). All data used to create the CRISPR–Cas Atlas are available in their original form by means of the IMG/M, ENA and NCBI databases. The OpenCRISPR-1 protein and gRNA sequences are provided at GitHub (https://github.com/Profluent-AI/OpenCRISPR). The OpenCRISPR-1 enzyme and corresponding guide plasmids have been deposited to the Addgene plasmid repository (IDs 221565, 221566 and 221567; https://www.addgene.org/browse/article/28248130). Plasmid maps and full plasmid sequence data are available there.

Code availability

Code and pretrained parameters for protein LMs were used according to the instructions provided in their official GitHub repositories. ProGen2 code and models are available at GitHub (https://github.com/salesforce/progen). ESM-2 code and models are available at GitHub (https://github.com/facebookresearch/esm). Fine-tuned model checkpoints for the CRISPR–Cas and Cas9 LMs are available at Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15128064)51. Code for PAM and tracrRNA compatibility and gRNA design is available at Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15231637)52.

References

-

Pacesa, M., Pelea, O. & Jinek, M. Past, present, and future of crispr genome editing technologies. Cell 187, 1076–1100 (2024).

-

Nijkamp, E., Ruffolo, J. A., Weinstein, E. N., Naik, N. & Madani, A. Progen2: exploring the boundaries of protein language models. Cell Syst. 14, 968–978 (2023).

-

Wu, Z. et al. Programmed genome editing by a miniature CRISPR–Cas12f nuclease. Nat. Chem. Biol. 17, 1132–1138 (2021).

-

Chen, K. et al. Lung and liver editing by lipid nanoparticle delivery of a stable CRISPR–Cas9 ribonucleoprotein. Nat. Biotechnol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-024-02437-3 (2024).

-

Eggers, A. R. et al. Rapid DNA unwinding accelerates genome editing by engineered CRISPR–Cas9. Cell 187, 3249–3261 (2024).

-

Nguyen, L. T. et al. Engineering highly thermostable Cas12b via de novo structural analyses for one-pot detection of nucleic acids. Cell Rep. Med.4, 101037 (2023).

-

Gasiunas, G. et al. A catalogue of biochemically diverse CRISPR–Cas9 orthologs. Nat. Commun. 11, 5512 (2020).

-

Casini, A. et al. A highly specific spCas9 variant is identified by in vivo screening in yeast. Nat. Biotechnol. 36, 265–271 (2018).

-

Hu, J. H. et al. Evolved Cas9 variants with broad pam compatibility and high DNA specificity. Nature 556, 57–63 (2018).

-

Lee, J. K. et al. Directed evolution of CRISPR–Cas9 to increase its specificity. Nat. Commun. 9, 3048 (2018).

-

Vakulskas, C. A. et al. A high-fidelity Cas9 mutant delivered as a ribonucleoprotein complex enables efficient gene editing in human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Nat. Med. 24, 1216–1224 (2018).

-

Chen, J. S. et al. Enhanced proofreading governs CRISPR–Cas9 targeting accuracy. Nature 550, 407–410 (2017).

-

Kleinstiver, B. P. et al. High-fidelity CRISPR–Cas9 nucleases with no detectable genome-wide off-target effects. Nature 529, 490–495 (2016).

-

Slaymaker, I. M. et al. Rationally engineered Cas9 nucleases with improved specificity. Science 351, 84–88 (2016).

-

Walton, R. T., Christie, K. A., Whittaker, M. N. & Kleinstiver, B. P. Unconstrained genome targeting with near-PAMless engineered CRISPR–Cas9 variants. Science 368, 290–296 (2020).

-

Dauparas, J. et al. Robust deep learning–based protein sequence design using ProteinMPNN. Science 378, 49–56 (2022).

-

Dauparas, J. et al. Atomic context-conditioned protein sequence design using ligandmpnn. Nat. Methods 22, 717–723 (2025).

-

Ruffolo, J. A. & Madani, A. Designing proteins with language models. Nat. Biotechnol. 42, 200–202 (2024).

-

Lin, Z. et al. Evolutionary-scale prediction of atomic-level protein structure with a language model. Science 379, 1123–1130 (2023).

-

Madani, A. et al. Large language models generate functional protein sequences across diverse families. Nat. Biotechnol. 41, 1099–1106 (2023).

-

Subramanian, A. M. & Thomson, M. Unexplored regions of the protein sequence-structure map revealed at scale by a library of foldtuned language models. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.12.22.573145 (2023).

-

Hopf, T. A. et al. The EVcouplings Python framework for coevolutionary sequence analysis. Bioinformatics 35, 1582–1584 (2019).

-

Russ, W. P. et al. An evolution-based model for designing chorismate mutase enzymes. Science 369, 440–445 (2020).

-

Trinquier, J., Uguzzoni, G., Pagnani, A., Zamponi, F. & Weigt, M. Efficient generative modeling of protein sequences using simple autoregressive models. Nat. Commun. 12, 5800 (2021).

-

Ferruz, N., Schmidt, S. & Höcker, B. ProtGPT2 is a deep unsupervised language model for protein design. Nat. Commun. 13, 1–10 (2022).

-

Johnson, S. R. et al. Computational scoring and experimental evaluation of enzymes generated by neural networks. Nat. Biotechnol. 43, 396–405 (2024).

-

Zetsche, B. et al. Cpf1 is a single RNA-guided endonuclease of a class 2 CRISPR–Cas9 system. Cell 163, 759–771 (2015).

-

Cox, D. B. T. et al. RNA editing with CRISPR–Cas13. Science 358, 1019–1027 (2017).

-

Anzalone, A. V., Koblan, L. W. & Liu, D. R. Genome editing with CRISPR–Cas nucleases, base editors, transposases and prime editors. Nat. Biotechnol. 38, 824–844 (2020).

-

Jumper, J. et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with alphafold. Nature 596, 583–589 (2021).

-

Chandonia, J.-M., Fox, N. K. & Brenner, S. E. Scope: classification of large macromolecular structures in the structural classification of proteins—extended database. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D475–D481 (2019).

-

Van der Maaten, L. & Hinton, G. Visualizing data using t-SNE. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 9, 2579–2605 (2008).

-

Conant, D. et al. Inference of CRISPR edits from sanger trace data. CRISPR J. 5, 123–130 (2022).

-

Tsai, S. Q. et al. Guide-seq enables genome-wide profiling of off-target cleavage by CRISPR–Cas nucleases. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 187–197 (2015).

-

Cameron, P. et al. Mapping the genomic landscape of CRISPR–Cas9 cleavage. Nat. Methods 14, 600–606 (2017).

-

Eddy, S. R. Accelerated profile HMM searches. PLoS Comput. Biol. 7, e1002195 (2011).

-

Schmid-Burgk, J. L. et al. Highly parallel profiling of Cas9 variant specificity. Mol. Cell 78, 794–800 (2020).

-

Alonso-Lerma, B. et al. Evolution of CRISPR-associated endonucleases as inferred from resurrected proteins. Nat. Microbiol. 8, 77–90 (2023).

-

Ferdosi, S. R. et al. Multifunctional CRISPR–Cas9 with engineered immunosilenced human T cell epitopes. Nat. Commun. 10, 1842 (2019).

-

Pacesa, M. et al. R-loop formation and conformational activation mechanisms of Cas9. Nature 609, 191–196 (2022).

-

Zhao, L. et al. Pam-flexible genome editing with an engineered chimeric Cas9. Nat. Commun. 14, 6175 (2023).

-

van Overbeek, M. et al. DNA repair profiling reveals nonrandom outcomes at Cas9-mediated breaks. Mol. Cell 63, 633–646 (2016).

-

Gaudelli, N. M. et al. Directed evolution of adenine base editors with increased activity and therapeutic application. Nat. Biotechnol. 38, 892–900 (2020).

-

Boutet, E. et al. in Plant Bioinformatics: Methods and Protocols (ed. Edwards, D.) Ch. 2 (Springer Nature, 2016).

-

Gaudelli, N. M. et al. Programmable base editing of A•T to G•C in genomic DNA without DNA cleavage. Nature 551, 464–471 (2017).

-

Nguyen, E. et al. Sequence modeling and design from molecular to genome scale with Evo. Science 386, eado9336 (2024).

-

Donohoue, P. D. et al. Conformational control of Cas9 by crispr hybrid RNA-DNA guides mitigates off-target activity in T cells. Mol. Cell 81, 3637–3649 (2021).

-

Huang, P.-S., Boyken, S. E. & Baker, D. The coming of age of de novo protein design. Nature 537, 320–327 (2016).

-

Chu, A. E., Lu, T. & Huang, P.-S. Sparks of function by de novo protein design. Nat. Biotechnol. 42, 203–215 (2024).

-

Watson, J. L. et al. De novo design of protein structure and function with RFdiffusion. Nature 620, 1089–1100 (2023).

-

Ruffolo, J. Fine-tuned language models for CRISPR–Cas and Cas9 protein generation. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15128064 (2025).

-

Ruffolo, J. Modeling code for design and prediction of Cas9-like proteins. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15231637 (2025).

-

Ciciani, M. et al. Automated identification of sequence-tailored Cas9 proteins using massive metagenomic data. Nat. Commun. 13, 6474 (2022).

-

Tang, Z. et al. CasPDB: an integrated and annotated database for Cas proteins from bacteria and archaea. Database 2019, baz093 (2019).

-

Coudert, E. et al. Annotation of biologically relevant ligands in UniProtKB using ChEBI. Bioinformatics 39, btac793 (2023).

-

Pourcel, C. et al. CRISPRCasdb a successor of CRISPRdb containing CRISPR arrays and cas genes from complete genome sequences, and tools to download and query lists of repeats and spacers. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, D535–D544 (2020).

-

Makarova, K. S. et al. Evolutionary classification of CRISPR-Cas systems: a burst of class 2 and derived variants. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 18, 67–83 (2020).

-

Price, M. N., Dehal, P. S. & Arkin, A. P. Fasttree 2—approximately maximum-likelihood trees for large alignments. PLoS ONE 5, e9490 (2010).

-

Letunic, I. & Bork, P. Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) v5: an online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, W293–W296 (2021).

-

Steinegger, M. & Söding, J. MMseqs2 enables sensitive protein sequence searching for the analysis of massive data sets. Nat. Biotechnol. 35, 1026–1028 (2017).

-

Mirdita, M. et al. ColabFold: making protein folding accessible to all. Nat. Methods 19, 679–682 (2022).

-

Van Kempen, M. et al. Fast and accurate protein structure search with foldseek. Nat. Biotechnol. 42, 243–246 (2024).

-

Fonfara, I. et al. Phylogeny of Cas9 determines functional exchangeability of Dual-RNA and Cas9 among orthologous type II CRISPR-Cas9 systems. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 2577–2590 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We thank J. Russel and R. P. Redondo for assistance with the CRISPR–Cas discovery pipeline, M. Martyn for help processing NGS data and D. Morris for advice on project conception.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

All authors are current or former employees, contractors or executives of Profluent Bio Inc and may hold shares in Profluent Bio Inc.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Fig. 1 Formation of the CRISPR-Cas Atlas.

a) Pipeline for discovery and annotation of 1.25 M CRISPR-Cas operons from 26.2 Tbp of genome and metagenome assemblies. b) Summary of different entities across the CRISPR-Cas atlas. c) Distribution of operon lengths across CRISPR-Cas types. d) 238,913 Cas9 proteins were identified from Type II CRISPR-Cas operons and clustered using MMseqs2. e) Comparison of the number of unique Cas9 proteins compared to previously published datasets7,53,54,55,56,57. UniProtKB was queried in March 2024 using search term: gene = Cas9. f) Length of 64,734 unique Cas9 proteins from the CRISPR-Cas Atlas. g) Summary statistics across 64,734 CRISPR-Cas operons. h) Phylogenetic tree of 8,441 Cas9s clustered at 70% identity. Phylogenetic tree built using FastTree258 and visualized using iTOL59.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Cumulative identity of natural and generated CRISPR-Cas proteins.

Comparison of sequence novelty for natural and generated CRISPR-Cas proteins, quantified by the cumulative percentage of positions matched by an aligned sequence from a reference database. a) Cumulative identity for 10,000 natural CRISPR-Cas proteins. Each line corresponds to the nearest reference sequence considered from the CRISPR-Cas Atlas. Points represent the median values, while shaded regions reflect the interquartile range. b) Cumulative identity for 10,000 generated CRISPR-Cas proteins. Each line corresponds to the nearest reference sequence considered from the CRISPR-Cas Atlas. Points represent the median values, while shaded regions reflect the interquartile range. c) Comparison of cumulative identity for natural and generated CRISPR-Cas proteins at similar levels of identity to the nearest reference sequence. Each line is composed of ten points, with each representing the median cumulative identity value of natural and generated proteins for a given number of reference sequences. Natural and generated CRISPR-Cas sequences show similar levels of novelty.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Structural composition of generated CRISPR-Cas proteins.

Generated and natural CRISPR-Cas proteins were clustered at 70% identity using MMseqs260. For both generated and natural proteins, random representatives of the largest 5,000 clusters were selected for structural analysis. Structures were predicted using the ColabFold61 implementation (v1.5.2) of AlphaFold230 using multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) from the ColabFoldDB (no templates). a) Generated sequences yield high confidence AlphaFold2 structure predictions despite significant sequence divergence from natural proteins. b) Predicted structures for generated proteins align well to experimentally determined structures from the PDB. c) Using Foldseek62 (v8.ef4e960), predicted structures for generated and natural proteins were searched against the SCOPe database31 (v2.08). Points in the left plot represent the fraction of generated (green) and natural (gray) proteins containing the twenty most commonly observed SCOPe families among both generated and natural sequences. Distributions in the right plot show the sequence identity over aligned residues between the generated and natural proteins and the best-matching SCOPe family structure. Overall, generated proteins were composed of similar structural components as compared to natural proteins, with levels of per-domain sequence similarity to particular SCOPe families being similar between the two sets of sequences. d) Examples of four most frequently observed SCOPe families (brown) aligned to generated (green) and natural (gray) proteins.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Cumulative identity of natural and generated Cas9 proteins.

Comparison of sequence novelty for natural and generated Cas9 proteins, quantified by the cumulative percentage of positions matched by an aligned sequence from a reference database. a) Cumulative identity for 10,000 natural Cas9 proteins. Each line corresponds to the nearest reference sequence considered from the CRISPRCas Atlas. Points represent the median values, while shaded regions reflect the interquartile range. b) Cumulative identity for 10,000 generated Cas9-like proteins. Each line corresponds to the nearest reference sequence considered from the CRISPR-Cas Atlas. Points represent the median values, while shaded regions reflect the interquartile range. c) Comparison of cumulative identity for natural and generated Cas9 proteins at similar levels of identity to the nearest reference sequence. Each line is composed of ten points, with each representing the median cumulative identity value of natural and generated proteins for a given number of reference sequences. Natural and generated Cas9 sequences show similar levels of novelty.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Structural composition of generated Cas9 proteins.

Generated and natural Cas9 proteins were clustered at 70% identity using MMseqs260. For both generated and natural proteins, random representatives of the largest 1,000 clusters were selected for structural analysis. Structures were predicted using the ColabFold61 implementation (v1.5.2) of AlphaFold230 using multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) from the ColabFoldDB (no templates). a) Generated sequences yield high confidence AlphaFold2 structure predictions despite significant sequence divergence from natural proteins. b) Predicted structures for generated proteins align well to experimentally determined structures from the PDB. c) Using Foldseek62 (v8.ef4e960), predicted structures for generated and natural proteins were searched against the SCOPe database31 (v2.08). Points in the left plot represent the fraction of generated (green) and natural (gray) proteins containing the ten most commonly observed SCOPe families. Distributions in the right plot show the sequence identity over aligned residues between the generated and natural proteins and the best-matching SCOPe family structure. Overall, generated proteins were composed of similar structural components as compared to natural proteins, with levels of per-domain sequence similarity to particular SCOPe families being similar between the two sets of sequences. d) Examples of four most frequently observed SCOPe families (brown) aligned to generated (green) and natural (gray) proteins.

Extended Data Fig. 6 gRNA model predicts exchangeability of RNAs between orthologous Cas9s.

a-c) crRNA:tracrRNA pairs were obtained for 1,591 distinct natural Cas9 sequences not used to train the gRNA model. The gRNA model was used to score native RNA:protein and non-native RNA:protein interactions. Additionally, pairwise identity was computed between RNA and protein sequences. a) RNA sequences diverge along with Cas9, but at a slower rate. b) RNA edit distance is correlated with the gRNA model score. c) gRNA model scores remain high for gRNAs exchanged between Cas9 proteins that display >70% identity. d) In 2013, Fonfara et al. tested the exchangeability of dual guide RNAs in vitro between eight diverse Type II CRISPR-cas systems63. DNA cleavage rates from Fonfara et al. are displayed in the figure as: +++: 75–100%, ++: 50–75%, +: 25–50%. We applied the gRNA model to score each pair of Cas9:RNA sequence pairs. The gRNA model outputs a log likelihood for each protein:RNA pairing. The matrix shows a relative gRNA compatibility score, quantified as the softmax over the RNA log likelihoods for each protein. Note: Fonfara et al. also tested F. novicida Cas9 and RNA molecules; however, because the tracrRNA for this and related proteins were not found in our training set, we excluded F. novicida from this analysis.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Experimental characterization of alternative natural and designed nucleases.

On- and off-target editing efficiency at five sites (AAVs1, HEK2, HEK3, FANCF, and VEGFA) for natural Cas9s, high-fidelity variants, chimeric sequences, consensus designs, ancestral reconstructions, HMM emissions, arDCA designs, LigandMPNN designs, and generated proteins from this work. Points correspond to on- or off-target editing at five sites (with three off-targets per site). Bars reflect the median of all on- and off-target editing. All sequences, aside from those generated by language models, had their PAM-interacting domain fixed to match that of SpCas9 to facilitate comparison at the same target sites. S. cristatus Cas9, the closest natural protein to OpenCRISPR-1, was only tested as a N626S point mutant, which may not have the same level of activity as the wild type sequence. The wild type sequence could not be cloned.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Comparison of SITE-Seq off-targets between SpCas9 and OpenCRISPR-1.

SITE-Seq was performed to identify off-targets for SpCas9 and OpenCRISPR-1 using five different guide RNAs and at four different RNPs concentrations.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Generated Cas9-like proteins are less immunogenic than SpCas9.

iELISA antibody quantification values indicate raw OD450nm values showing the amount of bound human antibody to each Cas9 protein. Plates were coated with purified proteins for SpCas9, PF-CAS-182 (OpenCRISPR-1), PF-CAS-189, and PF-CAS-151 at a concentration of 1 µg/mL (100 ng/well). Serum samples were diluted at 100-fold to 1600-fold. Generated Cas9-like proteins are less immunogenic than SpCas9 at one or more sample dilution levels.

Extended Data Fig. 10 Structural analysis of OpenCRISPR-1.

The structure of the OpenCRISPR1 protein was predicted with AlphaFold230 using multiple-sequence alignments from ColabFoldDB61 and template structure of SpCas9’s catalytic state (PDB: 7Z4J). The predicted protein structure was aligned to complex with the sgRNA and DNA. a) Structural model of OpenCRISPR-1 effector complex in catalytic state. Insertions in the HNH and REC1 domains with potential functional implications are highlighted. b) Analysis of OpenCRISPR-1 mutational distribution relative to SpCas9 according to residue burial (top) and whether a residue is in contact (<4.0 Å) with nucleic acids (bottom). Residue burial was not a significant determinant of mutational distribution, while nucleic-acid contacting residues were significantly depleted in mutations (chi-squared contingency test, p < 0.05). c) Nine-residue positively charged insertion in the REC1 domain of OpenCRISPR-1, which introduces stabilizing interactions with the phosphate backbone of the guide RNA’s repeat:anti-repeat segment and the target DNA’s PAM-proximal region. d) Four-residue insertion in the HNH domain of OpenCRISPR-1 modeled in the checkpoint state (PDB: 7Z4L), which may serve to stabilize the cleavage checkpoint state.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ruffolo, J.A., Nayfach, S., Gallagher, J. et al. Design of highly functional genome editors by modelling CRISPR–Cas sequences. Nature (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09298-z

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09298-z