Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the Article and its Supplementary Information. Source data are provided with this paper. All other data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

-

Ballabio, A. & Bonifacino, J. S. Lysosomes as dynamic regulators of cell and organismal homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 21, 101–118 (2020).

-

Mindell, J. A. Lysosomal acidification mechanisms. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 74, 69–86 (2012).

-

Johnson, D. E., Ostrowski, P., Jaumouille, V. & Grinstein, S. The position of lysosomes within the cell determines their luminal pH. J. Cell Biol. 212, 677–692 (2016).

-

Zhang, C. S. et al. The lysosomal v-ATPase–Ragulator complex is a common activator for AMPK and mTORC1, acting as a switch between catabolism and anabolism. Cell. Metab. 20, 526–540 (2014).

-

Nixon, R. A. & Rubinsztein, D. C. Mechanisms of autophagy–lysosome dysfunction in neurodegenerative diseases. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 25, 926–946 (2024).

-

Kim, J. & Guan, K. L. mTOR as a central hub of nutrient signalling and cell growth. Nat. Cell Biol. 21, 63–71 (2019).

-

McKenney, R. J., Huynh, W., Tanenbaum, M. E., Bhabha, G. & Vale, R. D. Activation of cytoplasmic dynein motility by dynactin–cargo adapter complexes. Science 345, 337–341 (2014).

-

Davis, L. C., Morgan, A. J. & Galione, A. Optical profiling of autonomous Ca2+ nanodomains generated by lysosomal TPC2 and TRPML1. Cell. Calcium 116, 102801 (2023).

-

Chen, Q. et al. Structure of mammalian endolysosomal TRPML1 channel in nanodiscs. Nature 550, 415–418 (2017).

-

Chen, W., Motsinger, M. M., Li, J., Bohannon, K. P. & Hanson, P. I. Ca2+-sensor ALG-2 engages ESCRTs to enhance lysosomal membrane resilience to osmotic stress. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2318412121 (2024).

-

Li, X. et al. A molecular mechanism to regulate lysosome motility for lysosome positioning and tubulation. Nat. Cell Biol. 18, 404–417 (2016).

-

Freeman, S. A., Grinstein, S. & Orlowski, J. Determinants, maintenance, and function of organellar pH. Physiol. Rev. 103, 515–606 (2023).

-

Xu, H. & Ren, D. Lysosomal physiology. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 77, 57–80 (2015).

-

Hu, M. et al. Parkinson’s disease-risk protein TMEM175 is a proton-activated proton channel in lysosomes. Cell 185, 2292–2308 (2022).

-

Ponsford, A. H. et al. Live imaging of intra-lysosome pH in cell lines and primary neuronal culture using a novel genetically encoded biosensor. Autophagy 17, 1500–1518 (2021).

-

Webb, B. A. et al. pHLARE: a new biosensor reveals decreased lysosome pH in cancer cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 32, 131–142 (2021).

-

Lesiak, L., Dadina, N., Zheng, S., Schelvis, M. & Schepartz, A. A bright, photostable, and far-red dye that enables multicolor, time-lapse, and super-resolution imaging of acidic organelles. ACS Cent. Sci. 10, 19–27 (2024).

-

Leung, K., Chakraborty, K., Saminathan, A. & Krishnan, Y. A DNA nanomachine chemically resolves lysosomes in live cells. Nat. Nanotechnol. 14, 176–183 (2019).

-

Tinker, J., Anees, P. & Krishnan, Y. Quantitative chemical imaging of organelles. Acc. Chem. Res. 57, 1906–1917 (2024).

-

Jo, M. H. et al. Determination of single-molecule loading rate during mechanotransduction in cell adhesion. Science 383, 1374–1379 (2024).

-

Nakamura, A. et al. Designer palmitoylation motif-based self-localizing ligand for sustained control of protein localization in living cells and Caenorhabditis elegans. ACS Chem. Biol. 15, 837–843 (2020).

-

Helms, J. B. & Rothman, J. E. Inhibition by brefeldin A of a Golgi membrane enzyme that catalyses exchange of guanine nucleotide bound to ARF. Nature 360, 352–354 (1992).

-

Ohkuma, S., Moriyama, Y. & Takano, T. Identification and characterization of a proton pump on lysosomes by fluorescein-isothiocyanate-dextran fluorescence. PNAS 79, 2758–2762 (1982).

-

Bright, N. A., Gratian, M. J. & Luzio, J. P. Endocytic delivery to lysosomes mediated by concurrent fusion and kissing events in living cells. Curr. Biol. 15, 360–365 (2005).

-

Modi, S. et al. A DNA nanomachine that maps spatial and temporal pH changes inside living cells. Nat. Nanotechnol. 4, 325–330 (2009).

-

Chen, C. S., Chen, W. N., Zhou, M., Arttamangkul, S. & Haugland, R. P. Probing the cathepsin D using a BODIPY FL-pepstatin A: applications in fluorescence polarization and microscopy. J. Biochem. Biophys. Methods 42, 137–151 (2000).

-

Creasy, B. M., Hartmann, C. B., White, F. K. & McCoy, K. L. New assay using fluorogenic substrates and immunofluorescence staining to measure cysteine cathepsin activity in live cell subpopulations. Cytometry Part A 71, 114–123 (2007).

-

Llopis, J., McCaffery, J. M., Miyawaki, A., Farquhar, M. G. & Tsien, R. Y. Measurement of cytosolic, mitochondrial, and Golgi pH in single living cells with green fluorescent proteins. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 95, 6803–6808 (1998).

-

Cang, C., Aranda, K., Seo, Y. J., Gasnier, B. & Ren, D. TMEM175 is an organelle K+ channel regulating lysosomal function. Cell 162, 1101–1112 (2015).

-

Rothemund, P. W. K. Folding DNA to create nanoscale shapes and patterns. Nature 440, 297–302 (2006).

-

Chung, C. Y. et al. Covalent targeting of the vacuolar H+-ATPase activates autophagy via mTORC1 inhibition. Nat. Chem. Biol. 15, 776–785 (2019).

-

Abu-Remaileh, M. et al. Lysosomal metabolomics reveals V-ATPase- and mTOR-dependent regulation of amino acid efflux from lysosomes. Science 358, 807–813 (2017).

-

Korolchuk, V. I. et al. Lysosomal positioning coordinates cellular nutrient responses. Nat. Cell Biol. 13, 453–460 (2011).

-

Pu, J., Guardia, C. M., Keren-Kaplan, T. & Bonifacino, J. S. Mechanisms and functions of lysosome positioning. J. Cell Sci. 129, 4329–4339 (2016).

-

Ratto, E. et al. Direct control of lysosomal catabolic activity by mTORC1 through regulation of V-ATPase assembly. Nat. Commun. 13, 4848 (2022).

-

Liu, Q. et al. Discovery of 1-(4-(4-propionylpiperazin-1-yl)-3-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-9-(quinolin-3-yl)benzo[h][1,6]naphthyridin-2(1H)-one as a highly potent, selective mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor for the treatment of cancer. J. Med. Chem. 53, 7146–7155 (2010).

-

Martinez-Lopez, N. et al. Autophagy in the CNS and periphery coordinate lipophagy and lipolysis in the brown adipose tissue and liver. Cell Metab. 23, 113–127 (2016).

-

Blauwendraat, C. et al. Parkinson’s disease age at onset genome-wide association study: Defining heritability, genetic loci, and alpha-synuclein mechanisms. Movement Disord. 4, 866–875 (2019).

-

Sun, W. et al. TMEM175, SCARB2 and CTSB associations with Parkinson’s disease risk across populations. npj Parkinsons Dis. 11, 348 (2025).

-

Luk, K. C. et al. Pathological alpha-synuclein transmission initiates Parkinson-like neurodegeneration in nontransgenic mice. Science 338, 949–953 (2012).

-

Wen, X. et al. Evolutionary study and structural basis of proton sensing by Mus GPR4 and Xenopus GPR4. Cell 188, 653–670 (2025).

-

Wu, Z. et al. Regulation of inflammatory responses by pH-dependent transcriptional condensates. Cell 188, 5632–5652 (2025).

-

Saminathan, A. et al. A DNA-based voltmeter for organelles. Nat. Nanotechnol. 16, 96–103 (2021).

-

Koivusalo, M., Steinberg, B. E., Mason, D. & Grinstein, S. In situ measurement of the electrical potential across the lysosomal membrane using FRET. Traffic 12, 972–982 (2011).

-

Yamaguchi, T., Aharon, G. S., Sottosanto, J. B. & Blumwald, E. Vacuolar Na+/H+ antiporter cation selectivity is regulated by calmodulin from within the vacuole in a Ca2+– and pH-dependent manner. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 16107–16112 (2005).

-

Prinz, W. A., Toulmay, A. & Balla, T. The functional universe of membrane contact sites. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 21, 7–24 (2020).

-

Zheng, Q. et al. Calcium transients on the ER surface trigger liquid-liquid phase separation of FIP200 to specify autophagosome initiation sites. Cell 185, 4082–4098 (2022).

-

Medina, D. L. et al. Lysosomal calcium signalling regulates autophagy through calcineurin and TFEB. Nat. Cell Biol. 17, 288–299 (2015).

-

Hu, M. et al. The ion channels of endomembranes. Physiol. Rev. 104, 1335–1385 (2024).

-

Voeltz, G. K., Sawyer, E. M., Hajnóczky, G. & Prinz, W. A. Making the connection: how membrane contact sites have changed our view of organelle biology. Cell 187, 257–270 (2024).

-

Voeltz, G. K., Rolls, M. M. & Rapoport, T. A. Structural organization of the endoplasmic reticulum. EMBO Rep. 3, 944–950 (2002).

-

Jahreiss, L., Menzies, F. M. & Rubinsztein, D. C. The itinerary of autophagosomes: from peripheral formation to kiss-and-run fusion with lysosomes. Traffic 9, 574–587 (2008).

-

Maday, S., Wallace, K. E. & Holzbaur, E. L. Autophagosomes initiate distally and mature during transport toward the cell soma in primary neurons. J. Cell Biol. 196, 407–417 (2012).

-

Kimura, S., Noda, T. & Yoshimori, T. Dynein-dependent movement of autophagosomes mediates efficient encounters with lysosomes. Cell Struct. Funct. 33, 109–122 (2008).

-

Zou, J. et al. A DNA nanodevice for mapping sodium at single-organelle resolution. Nat. Biotechnol. 42, 1075–1083 (2024).

-

Ebrahimi, S. B., Samanta, D. & Mirkin, C. A. DNA-based nanostructures for live-cell analysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 11343–11356 (2020).

-

Zhang, X. et al. Rapamycin directly activates lysosomal mucolipin TRP channels independent of mTOR. PLoS Biol. 17, e3000252 (2019).

-

Ran, F. A. et al. Genome engineering using the CRISPR–Cas9 system. Nat. Protoc. 8, 2281–2308 (2013).

-

Zhong, Z. et al. Prion-like protein aggregates exploit the RHO GTPase to cofilin-1 signaling pathway to enter cells. EMBO J. 37, e97822 (2018).

-

Lin, M. et al. A biomimetic approach for spatially controlled cell membrane engineering using fusogenic spherical nucleic acid. Angew. Chem. 61, e202111647 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 92354306 to H.X., 92253304 to L.Q., T2188102 to W.T., 22174039 to L.Q., 32421001 to H.X., 22404051 to Z.W. and 32570805 to M.H.), National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant nos. 2021YFA0910101 to L.Q. and 2022YFE0210100 to H.X.), National Science and Technology Major Project of China (grant no. 2025ZD0215900 to M.H.), the Science and Technology Project of Hunan Province 2021RC4022 to L.Q., the Health Commission of Zhejiang Province Grant WKJ-ZJ-2103 to W.T. and the Investigator Program from New Cornerstone Science Foundation to H.X.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

H.X. is the scientific cofounder and a partial owner of Lysoway Therapeutics Inc. (Boston) and Lyso-X Therapeutics Inc. (Hangzhou). The other authors declare no competing financial interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Cell Biology thanks Peter Kreuzaler and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

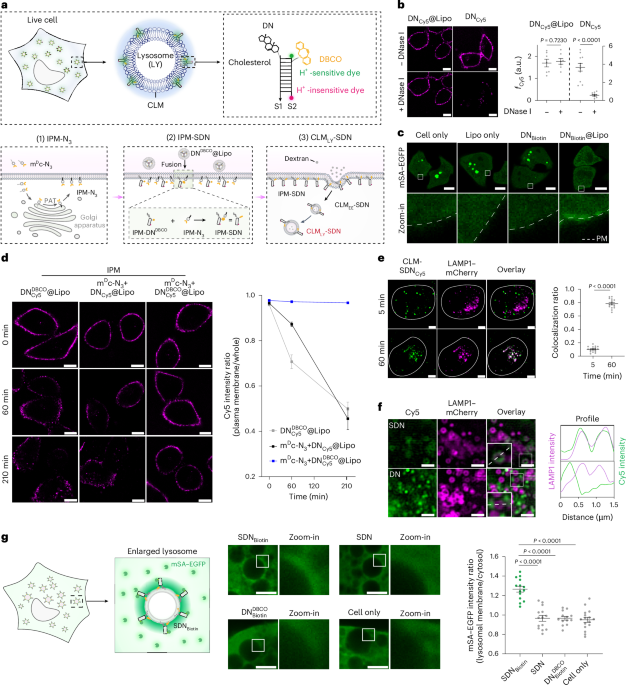

Extended Data Fig. 1 Efficient decoration of an N3 tag on the inner plasma membrane (IPM).

a, Chemical structures of mDc-N3 and IPM-N3. b, The membrane penetration kinetics of Silorhodamine (SiR)-DBCO. Left: Representative confocal images of HeLa cells incubated with 10 μM SiR-DBCO at 37 °C for different time spans (scale bar, 10 µm). Right: Summary of time-dependent SiR fluorescence intensity (n = 30, 30, and 31 cells for the left to right groups, respectively). c, Schematic illustration of the experimental workflow for construction of IPM-N3. d, Representative confocal images of SiR-DBCO-pretreated HeLa cells processed with or without 10 μM mDc-N3 at RT for 10 min, and then incubated in fresh culture medium for different time spans (scale bar, 10 µm). e, Schematic illustration of the experimental workflow for quantification of SiR-DBCO within cells. f, Left: Construction of the standard calibration curve of SiR-DBCO. Right: Fluorescence spectra of the lysate of HeLa cells after treatment with 10 μM SiR-DBCO at 37 °C for 60 min. g, Quantification of IPM-DNs. Construction of the standard calibration curve of DNCy5 in buffer solution (Standard curve 1), DNCy5 on the outer membrane of cells (Standard curve 2), and grey value of Cy5 in confocal microscope images (Standard curve 3). h, Summary of time-dependent changes of SiR fluorescence ratio between the plasma membrane and whole cell in SiR-DBCO-pretreated HeLa cells incubated with mDc-N3 (Left to right groups: n = 10, 10, 13, and 12 cells for mDc-N3 treated group; n = 12, 12, 13, and 13 cells for control group without mDc-N3 treatment). i, Representative confocal images of HeLa cells treated with mDc-N3 for 45 min (scale bar, 10 μm, green fluorescence = DIO for plasma membrane staining). j, Cellular distribution of the N3 tag. Representative confocal images of HeLa cells processed with SiR-DBCO/mDc-N3 and then stained with 100 nM Golgi Apparatus (GA) tracker, Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER) tracker, or Mitochondria (Mito) tracker (scale bar, 10 µm). k, Golgi apparatus-mediated metabolic process of mDc-N3. Representative confocal images of HeLa cells pretreated with 10 μM palmitoylation inhibitor 2-bromopalmitate (2-BP) (upper) or 20 μM Golgi disrupter Brefeldin A (BFA) (lower) at 37 °C for 60 min, and then processed with SiR-DBCO/mDc-N3 (scale bar, 10 µm). l, The IPM orientation of the N3 tag. Representative confocal images of mSA-EGFP-transfected HeLa cells processed with mDc-N3, and then incubated with DBCO-PEG4-Biotin at RT for 30 min (scale bar, 10 μm (upper) and 2.5 μm (lower)). Statistical data are presented as mean ± s.d. (b) or mean ± s.e.m. (h), with n as randomly selected cells from 3 biological repeats. For panel d and i-l, 3 independent experiments are repeated with similar results.

Extended Data Fig. 2 IPM-stabilized DNA nanodevices are sequentially delivered to early endosomes and lysosomes through endosome maturation without affecting lysosomal functions.

a, Left: Representative confocal images of SDNCy5-engineered HeLa cells pulsed with 1 mg/mL Rhodamine-labeled dextran (RB-dextran) for 30 min and then chased for different time spans (scale bar, 10 μm). Right: Summary of colocalization ratio between RB-dextran and SDNCy5 (n = 12, 12, and 11 cells for the left to right groups, respectively). b, Left: Representative confocal images of HeLa cells pulsed with 1 mg/mL RB-dextran for 30 min and then chased for different time spans (scale bar, 10 µm, green fluorescence = LysoTracker for lysosome staining). Right: Summary of colocalization ratio between RB-dextran and LysoTracker (n = 10 cells for each group). c, Organellar localization of SDN. Left: Representative confocal images of Rab5-mCherry-transfected HeLa cells engineered with IPM-SDNCy5, and then pulsed with dextran and chased for 5 min and 60 min (scale bar, 5 μm). Right: Summary of time-dependent colocalization ratios between Cy5 and mCherry (n = 14 and 12 cells for 5 min and 60 min, respectively). d, Organellar localization of SDN. Left: Representative confocal images of HeLa cells decorated with IPM-SDNCy5, pulsed with dextran and chased for 60 min, then immuno-stained with anti-LAMP1 (lysosome), anti-GM130 (Golgi apparatus), and anti-EEA1 (early endosome) antibodies (scale bar, 10 μm). Right: Summary of colocalization ratios between SDN and organelle markers (n = 5, 7, and 10 images for the left to right groups, respectively). e, Left: Representative confocal images of LAMP1-mCherry-transfected HeLa cells engineered with SDNCy5 and then incubated in fresh culture medium for 0 or 180 min (scale bar, 10 μm). Right: Summary of fluorescence ratios between Cy5 and mCherry (fCy5/fmCherry) at indicated time points (n = 159 and 144 lysosomes for 0 min and 180 min, respectively). f, Left: Representative confocal images of HeLa cells pretreated with CLMLY-SDN, and then incubated with Magic Red (2000× dilution) at RT for 30 min (scale bar, 20 µm). Right: Summary of the fluorescence intensity of Magic Red (n = 34 and 35 cells for the groups without and with CLMLY-SDN pretreatment, respectively). g, Left: Representative confocal images of HeLa cells pretreated with CLMLY-SDN, and then incubated with 1 mM Pepstatin A BODIPY at RT for 30 min (scale bar, 20 µm). Right: Summary of the fluorescence intensity of Pepstatin A BODIPY (n = 27 cells for each group). Untreated HeLa cells were used as a positive control. For all panels, statistical data are presented as mean ± s.d. (a, b, c and d) or as box-and-whiskers graphs (f and g), where the box represents the range of 25%-75%, the solid line inside means the mean level, and the whiskers represent the minimum and maximum, with n as randomly selected images/cells from ≥3 biological repeats. Two-tailed Student’s t test was used to assess statistical significance.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Construction of pH-reporting DNA nanodevices for measuring juxta-lysosomal pH.

a, Construction of DNFAM/Cy5. PAGE analyses of different DNA samples. From lane 1 to 4: S1; S2; DN (S1 + S2); 20-bp DNA ladder. S1 was labeled with a cholesterol tag. S2 was labeled with a FAM, a Cy5, and a DBCO tag. b, Fluorescence spectrum of the FAM and Cy5 dyes in a permeability buffer solution (DPBS containing 10 μM nigericin and 10 μM valinomycin) of pH ranging from 4.5 to 8.0. The excitation wavelength for FAM and Cy5 was set at 488 nm (λem = 500-550 nm) and 633 nm (λem = 650-700 nm), respectively. c, Summary of the FAM fluorescence versus the buffer pH. Red dotted line represents the pKa value of the FAM dye (n = 3 independent assays). d, The f1/f0 ratio of DNFAM/Cy5 incubated with Ca2+, Na+, K+, or Cs+ of 10 nM versus 10 mM in Tris-HCl buffer solutions. The fluorescence ratio fFAM/fCy5 (FAM: λex = 488 nm, λem = 520 nm; Cy5: λex = 633 nm, λem = 665 nm) of 10 nM was set as f0, and that of 10 mM was set as f1 (n = 3 independent assays). e, Summary of calibrated cytosolic (bulk cytosol) pH and juxta-lysosomal (Juxta-LY) pH values of primary mouse astrocytes, MCF-7 cells, and PC12 cells (Left to right groups: n = 14 and 5 images for astrocyte, 5 and 4 images for MCF-7, 4 and 7 images for PC12). f, Summary of calibrated juxta-lysosomal pH values in WT and Tmem175 KO MEF cells, as well as WT and TMEM175 KO U2OS cells, as measured with CLMLY-SDNFAM/Cy5 (Left to right groups: n = 9 and 10 images for MEF, 14 and 15 images for U2OS). For all panels, statistical data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. (d) or box-and-whiskers graphs (e and f), in which the box represents the range of 25%-75%, the solid line inside indicates the mean level, and the whiskers represent the minimum and maximum, with n as randomly selected images/cells from ≥3 biological repeats. Two-tailed Student’s t test was used to assess statistical significance.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Juxta-lysosomal pH of WT and TMEM175 KO cells determined using a lysosome-targeted, genetically-encoded pH indicator.

a, Schematic illustration of the design of a genetically-encoded, lysosome-targeted, juxta-lysosomal pH probe, in which both pH-sensitive pHluorin and pH-insensitive mCherry are fused with lysosomal membrane protein TMEM192 at the cytosolic side (mCherry-TMEM192-pHluorin). b, Representative confocal images of WT and TMEM175 KO HeLa cells transfected with mCherry-TMEM192-pHluorin (scale bar, 10 μm). Right panel shows the summary of calibrated juxta-lysosomal pH values (n = 12 and 21 images for WT and TMEM175 KO cells, respectively). For panel b, statistical data are presented as box-and-whiskers graphs, where the box represents the range of 25%-75%, the solid line inside means the mean level, and the whiskers represent the minimum and maximum with n as randomly selected images/cells from 3 biological repeats. Two-tailed Student’ s t test was used to assess statistical significance.

Extended Data Fig. 5 TMEM175-mediated H+ flux regulates juxta-lysosomal pH.

a, Representative confocal images of TMEM175 KO HeLa cells transfected with D41A (a selective H+-conductance-deficient mutant with normal K+ permeability) or S45A (normal H+ conductance but with reduced K+-permeability), using CLMLY-SDNFAM/Cy5 (scale bar, 10 μm). Green cycles indicate transfected cells. Right panel shows the summary of juxta-lysosomal pH (n = 9 and 10 images for TMEM175 KO cells transfected with S45A and D41A, respectively). The red dashed line represents the juxta-lysosomal pH of TMEM175 KO HeLa cells. b, Arachidonic acid (ArA) induced juxta-lysosomal pH reduction in WT, but not TMEM175 KO HeLa cells. Representative images of CLMLY-SDNFAM/Cy5-engineered WT and TMEM175 KO HeLa cells treated with or without ArA (100 μM, scale bar, 10 μm). Right panel shows the summary of juxta-lysosomal pH (n = 8, 8, 9, and 7 images for the left to right groups, respectively). For all panels, statistical data are presented as box-and-whiskers graphs, where the box represents the range of 25%-75%, the solid line inside means the mean level, and the whiskers represent the minimum and maximum, with n as randomly selected images from 3 biological repeats. Two-tailed Student’s t test was used to assess statistical significance.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Surface conjugation with DNA duplexes for measuring the thickness of an acidic layer.

a, Schematic illustration of liposomes anchored with 15-bp, 29-bp, or 52-bp DNA duplex; Right panels show the Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) profiles of a naked liposome and liposomes conjugated with DNA duplexes of given base pair numbers. b, Correlative analysis of the liposomal diameter versus the number of DNA base pairs (n = 3 independent experiments). c, Summary of DNA duplex thickness on the liposomal surface (n = 3 independent experiments). For all panels, statistical data are presented as mean ± s.d. Two-tailed Student’s t test was used to assess statistical significance.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Simultaneous monitoring of both intra-lysosomal and juxta-lysosomal acidities.

a, Scheme diagram of the tandem tagBFP-mNectarine-LAMP1-sfGFP probe to monitor intra-lysosomal and juxta-lysosomal acidities simultaneously. The pH-sensitive mNectarine and sfGFP are fused with LAMP1 at cytosolic side and luminal side, respectively, with the tandem pH-insensitive tagBFP (BFP) fused at cytosolic side serves as internal reference. The fluorescence intensity of both mNectarine and sfGFP becomes stronger upon de-acidification (that is, pH elevation). b, Representative fluorescence images of WT and TMEM175 KO HeLa cells expressing tagBFP-mNectarine-LAMP1-sfGFP probes in response to DCPIB (100 μM; scale bar, 10 μm). c, Summary of ratio intensity of sfGFP to tagBFP (to indicate intra-lysosomal acidity) and mNectarine to tagBFP (to indicate juxta-lysosomal acidity) (n = 48, 47, 48, 47, 56, 60, 56 and 60 cells for the left to right groups, respectively). For all panels, statistical Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. with n as randomly selected cells from ≥ 3 biological repeats. Two-tailed Student’s t test was used to assess statistical significance.

Extended Data Fig. 8 TMEM175 regulates lysosomal distribution in primary mouse neurons.

a, Summary of juxta-lysosomal acidity determined by using the genetically-encoded mCherry-TMEM192-pHluorin indicator (n = 16, 15, 18, and 13 images for the left to right groups, respectively). The increase of fluorescence ratio (pHluorin vs. mCherry) corresponds to the reduction of juxta-lysosomal acidity (that is, pHjx-LY elevation). b, Representative confocal images of WT and Tmem175 KO mouse neurons treated with or without 3 μg/mL α-synuclein preformed fibril (pff) for 7 days, and stained with anti-LAMP2 and anti-MAP2 antibodies (white dotted line represents soma region; scale bar, 10 μm). c, Summary of LAMP2 immunofluorescence in the soma relative to whole cell (n = 14, 12, 24, and 14 neurons for the left to right groups, respectively). For all panels, statistical data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. with n as randomly selected images/cells from 2 biological repeats. Two-tailed Student’s t test are used to assess statistical significance.

Extended Data Fig. 9 RILP acts as a juxta-lysosomal pH sensor in regulating lysosome retrograde transport.

a, RILP mediates nutrient-sensitive regulation of lysosome perinuclear positioning. Representative confocal images of LAMP1-transfected WT and TMEM175 KO HeLa cells treated with Torin 1 (200 nM, scale bar, 10 μm). b, RILP clustering is decreased in Baf-A1-treated WT cells or TMEM175 KO HeLa cells. Left: Representative confocal images of WT (treated with or without 1 μM Baf-A1) and TMEM175 KO HeLa cells transfected with RILP-EGFP (scale bar, 10 μm). Right: Summary of LAMP1 intensity ratios on RILP puncta relative to whole-cell (n = 52, 50, and 44 cells for the left to right groups, respectively). Green line represents RILP positively-transfected cells. c, Sequence alignment analyses reveal conserved histidine residues in RILP. RILP and RILP-like protein 1 from different species, including human, mouse, danio rerio (DANRE), bos taurus (BOVIN), and xenopus tropicalis (XENLA), were used for analysis. d, Left: Representative confocal images of WT HeLa cells transfected with WT or mutant (H30A, H130A, H203A, H160A, H160D, H160K, H205A, H280A, H332A, H388A, or H390A) RILP-EGFP (scale bar, 10 μm). Right: Summary of the intensity ratios of LAMP1 versus RILP puncta in whole cell (n = 45, 30, 22, 46, 37, 32, 36, 28, 31, 38, 28, and 44 cells for the left to right groups, respectively). Green solid cycles indicate RILP-transfected cells. e, Representative confocal images of RILP KO HeLa cells transfected with various RILP-EGFP WT and mutant constructs (scale bar, 20 μm). Green solid lines indicate RILP-transfected cells. For all panels, statistical data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. with n as randomly selected cells from 3 biological repeats. Two-tailed Student’s t test are used to assess statistical significance.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Methods, Supplementary Figs. 1–16, Supplementary Tables 1 and 2, unprocessed western blot images, References, and light microscopy reporting table.

Reporting Summary

Supplementary Movie 1

Living imaging of intracellular localization of SDN. Time-lapse confocal imaging of LAMP1–mCherry- or EEA1–mCherry-transfected HeLa cells engineered with SDNCy5 for 120 min (scale bar, 5 μm).

Source data

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Y., Hu, M., Meng, Y. et al. DNA nanodevices detect an acidic nanolayer on the lysosomal surface. Nat Cell Biol (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41556-025-01855-y

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

Version of record:

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41556-025-01855-y