Introduction

Even after decades of clinical and experimental research, the treatment of esophageal cancer (EC) patients still remains challenging. EC, particularly esophageal adenocarcinoma, is currently the most rapidly increasing solid malignancy in the United States and the Western world [1]. Unfortunately, due to the paucity of symptoms associated with this condition, patients usually present with advanced stage disease. Dysphagia (difficulty swallowing), the most common symptom of EC, does not develop until approximately two-thirds of the esophageal lumen has been obliterated [2]. Thus, the majority of patients do not qualify for esophagectomy (surgical removal of all or part of the esophagus) due to their advanced disease stage or the presence of other medical conditions [3]. Many also refuse surgery due to the potential for serious complications and its high mortality rate, ranging from 4 to 11% within 30 days of surgery [4, 5]. As a result, palliative chemoradiation therapy aimed at relieving symptoms and potentially prolonging survival remains the only option for patients with advanced EC [6]. To access this care often means that patients must travel away from home. According to a recent study, EC patients currently spend approximately 37 days away from home in health care facilities just to receive chemotherapy [7]. Many rural areas lack specialized medical facilities, equipment, and trained personnel. Additionally, transportation can be a significant issue in rural areas, particularly for patients who require frequent treatments [8]. Thus, fundamentally new methods of care are needed to effectively treat EC patients in an outpatient setting without disrupting their daily living and quality of life.

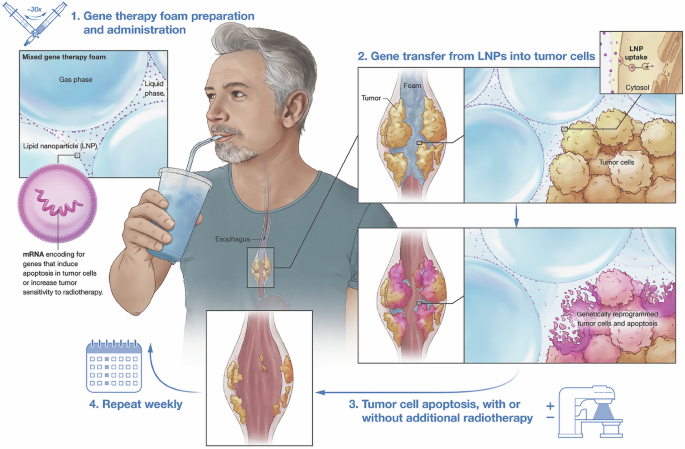

Our group has recently discovered that embedding gene therapy vector (nonviral or viral) in a methylcellulose/xanthan gum-based foam formulation substantially boosts their transfection efficiencies in situ, compared to liquid-based gene therapy, without triggering toxicities [9]. Here, we developed a drinkable gene therapy foam with anti-tumor properties, since we believe that EC is the ideal clinical application of this platform (as illustrated in Fig. 1). A wide variety of therapeutic genes to treat solid malignancies have been described in the literature, including (1) CRISPR-Cas9 systems that silence critical drivers of the disease [10], (2) transgenes that improve the efficiency of chemotherapy or radiation [11], (3) tumor suppressor genes [12], (3) genes that suppress migration and invasion of cancer cells [13], (4) immunomodulatory genes [14, 15], (5) suicide/cytotoxic genes [16], (6) antiangiogenic genes [17], or (7) oncolytic virotherapy [18]. However, cancer gene therapy is currently not practiced in EC patients, as tools are missing to deliver therapeutic gene therapy agents. Having the patient swallow a liquid solution of gene therapy is inefficient and unsafe, because the liquid diffuses and drains away in an unpredictable manner. In stark contrast, orally administered gene therapy foam could coat the esophagus and form a local reservoir that slowly releases the cancer-killing gene therapy drug at the tumorous stricture. To test this hypothesis, we developed a simplified in vitro tissue model of advanced EC, recapitulating an esophageal tube lined with mucus-producing epithelial cells with an ingrowing adenocarcinoma near the distal end. We also simulated lubrication and swallowing by pumping artificial saliva into the model esophagus at a flow rate similar to normal saliva production in humans. Using this model, we demonstrate that foam efficiently accumulates at the esophageal tumor constriction and substantially boosts gene transfer (mediated by mRNA lipid nanoparticles) into obstructive EC lesions, compared to liquid gene therapy. This action improved cancer killing and clearance by 110-fold when delivering mRNA that encodes an apoptosis-inducing protein (Pseudomonas exotoxin A). We also show that combining gene therapy foam with radiation therapy substantially improves tumor killing.

Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) containing mRNA encoding genes that trigger tumor apoptosis are embedded in freshly prepared methylcellulose/xanthan gum-based foam using a simple syringe mixing technique (not shown). This creates a microfoam gene therapy vector. This medication is then orally administered to the patient to coat the esophagus and form a local reservoir that slowly releases the gene therapy drug at the tumorous esophageal stricture. Gene therapy foam treatments could be repeated as medically necessary and combined with standard-of-care radiotherapy to further boost the cancer-killing effect.

Results

Establishing a clinically relevant in vitro EC model

Foam is mostly air (80–90% of total volume) and therefore cannot be dispensed in volumes of less than ~500 μL. It is therefore not possible to study the therapeutic potential of drinkable gene therapy foam in small animal models of EC, such as mice (esophagus volume: 10-20 μL [19]) or rats (esophagus volume: 150–200 μL [20]). Hence, to test our new concept, we developed a simplified in vitro tissue model of a human esophagus (at a ~ 1:2 scale) narrowed by an ingrowing esophageal carcinoma (Fig. 2). We first cultured a monolayer of mucus-producing human epithelial cells (HT29-MTX-E12) on the inner surface of a tissue culture-treated tube to model the healthy section of the esophagus. Then, to model a tumorous obstruction, we grew human OACM5.1 C esophageal carcinoma cells in three-dimensional collagen plugs, and placed them into the distal part of the esophagus tubing to narrow its lumen (Fig. 2, right panel). To simulate lubrication and swallowing, we pumped mucin-containing artificial saliva into the model esophagus at a 30 mL/hour flow rate, which mimics a normal 60 mL/hour saliva production in humans (with an esophagus ~twice the size of our tissue model) [21].

a Photo of the setup, which includes a syringe pump to pump artificial saliva into the model esophagus, a tube lined with a monolayer of mucus secreting epithelial cells, and a tumorous obstruction in the distal part of the esophagus tubing. b Close-up photo of the esophageal tube. c Light microscopy image of HT29-MTX-E12 cells lining the inner wall of the tube. Cells were stained with Alcian Blue to visualize mucus. Scale bar: 50 μm. d Light microscopy image of OACM5.1 C esophageal carcinoma cells in three-dimensional collagen plugs. Cross sections were stained with Neutral Red to better visualize cells. Scale bar: 25 μm. e Close-up photo of the esophageal tube with inserted tumor plugs from below.

Foam efficiently accumulates at obstructing EC lesions and boosts gene transfer

To directly visualize differences in fate and dynamics of foam versus liquid as they pass through the esophagus with a constricting lesion, we generated time lapse videos. We first added glow-in-the-dark UV black-light pigments to a 0.8% methylcellulose/0.5% xanthan gum foam precursor solution or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) suspension to be able to easily track the carriers under black light. The concentration of xanthan gum, a widely used food additive to increase volume, texture and viscosity [22], was optimized in prior experiments to improve foam stability while retaining its fluidity and drinkability (Supplementary Fig. 1). To generate homogenous foam, 1 mL of the foam precursor was mixed with 9 mL of air via 30 passes between two 10-mL syringes connected at 90° with a 3-way Luer adapter, as described previously [9] (also visualized in Supplementary Movie 1). We found that, foam initially passes through the esophageal tube relatively fast (within a few minutes), but then gradually accumulates at the therapeutically relevant tumor constriction and the junction between the esophagus and the tumor lesion (Fig. 3a, b; Supplementary Movie 2). Importantly, foam was not “stuck” in the esophagus, but was cleared within 20 min from the healthy upper section and moved down the esophagus toward the constriction by the steady saliva stream. In sharp contrast to foam, liquid suspension quickly drained through the malignant constriction with no substantial accumulation (Fig. 3a, b; Supplementary Movie 3).

a Representative frames of 2-hour time-lapse videos showing 4 mL liquid or methylcellulose/xanthan gum-based foam entering an esophageal tube narrowed at the bottom by esophageal tumor (OACM5.1 C tumor cells established in 3D collagen plugs). Videos were acquired under a black light and fluorescent UV dye was added to liquid and foam for easy detection. b Measured light intensities of foam versus suspension in two different regions of interest: (i) tumor region; (ii) upper esophagus. Light intensities were measured at 3 s intervals and plotted for the entire duration of the time-lapse video. c In vitro bioluminescence imaging of esophageal tubes and tumor plugs 24 h after administration of foam or suspension containing lipid nanoparticles loaded with mRNA encoding firefly luciferase. To avoid bioluminescence signal spillover, tumor plugs were removed from esophageal tubes prior to image acquisition. d Summary plots showing differences in gene transfer (bioluminescence signals) into the upper esophagus and EC tumor lesions, based on 5 independent experiments.

To measure differences in gene transfer into EC tumor lesions, we added 4 mL of foam or PBS suspension to this test system (each containing lipid nanoparticles; LNPs (Supplementary Fig. 2); loaded with 20 μg mRNA encoding luciferase). A control group was not exposed to gene therapy vector to measure background signals. After 24 h, we measured gene transfer (bioluminescent signals) into tumor using an IVIS® imaging system. We found that foam formulation boosts gene transfection efficiencies into EC tumors by an average 12.6-fold compared to liquid-based gene delivery (P = 0.0035; Fig. 3c; lower panel, Fig. 3d). While foam-mediated gene transfer was not restricted to the desired tumorous esophageal obstruction, most of the bioluminescent signal in the healthy section of the esophagus was measured at the junction between the esophagus and the tumor lesion (61.9% ±SD/19.2%; Fig. 3c; upper panel). Only in one out of five independent runs (replicate #2), significant off-target gene transfer into the upper esophagus was observed.

Foam mediates superior anti-tumor responses compared to liquid-based gene therapy

To measure the therapeutic advantage of drinkable foam as a gene therapy carrier for the treatment of EC, we fabricated mRNA LNPs with tumor-killing capabilities. To accomplish this, we replaced the mRNA encoding luciferase, used for our previous gene transfer experiments, with mRNA encoding the third domain, also known as the catalytic domain, of Pseudomonas exotoxin A (PEIII), as illustrated in Fig. 4a. This recombinant toxin acts as an inhibitor of protein synthesis by ribosylation of elongation factor 2 (EF2), which causes disruption in cell protein homeostasis and directs the cell towards apoptosis [23]. Based on its strong anti-tumor effects, PEIII is used in antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) that have gained Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for certain cancer treatments [24]. Recently, Dan Peer’s team at Tel Aviv University demonstrated that mRNA encoding PEIII can be encapsulated in liposomes to achieve potent intracellular effects while reducing potential side effects from toxin release [25, 26]. To assess the ability of PEIII mRNA LNPs to induce apoptosis in human esophageal carcinoma cells, we first incubated OACM5.1 C cells with increasing amounts of these liposome vectors. Forty-eight hours post transfection, we determined necrosis and apoptosis rates, using PI-Annexin-V staining and FACS analysis. We found that even a very low dose (6 ng LNP-encapsulated PEIII mRNA/mL) led to markedly increased apoptotic rates of tumor cells (average 44.4% ± SD/1.9%), compared to untreated controls (Fig. 4b, c). High LNP doses containing 1 μg of PEIII mRNA/mL triggered a massive 92.5%±SD/1.1% of cell to undergo apoptosis (Fig. 4b, c). Based on this encouraging data, we next embedded PEIII mRNA LNPs in freshly prepared methylcellulose/xanthan gum-based foam to test its therapeutic value for the treatment of obstructive EC, using our in vitro tissue model. To compare therapeutic anti-tumor responses by bioluminescence imaging, we lentivirally engineered OACM5.1 C esophageal carcinoma cells to express luciferase before growing them in three-dimensional collagen plugs and placing them into the distal part of the esophagus tubing to narrow its lumen. Tumor lesions were then treated with an equal dose of LNPs (delivered in 4 mL of foam or PBS suspension) encoding PEIII.

a Schematic illustration depicting gene therapy foam with anti-cancer activity, containing Pseudomonas A exotoxin (PEIII) mRNA liposomes. b Flow cytometry-based Annexin-V/Propidium Iodide (PI) assay to determine necrosis and apoptosis rates of OACM5.1 C esophageal carcinoma cells 48 h post transfection with increasing amounts of PEIII mRNA LNPs. Low dose: 6 ng LNP-encapsulated PEIII mRNA/mL; High dose: 1 μg LNP-encapsulated PEIII mRNA/mL. Representative FACS plots from three independent experiments are shown. c Graphical representation of PI-Annexin-V-stained OACM5.1 C tumor cells according to their viability state: live (Annexin V-negative and PI-negative), necrotic (Annexin V-negative and PI-positive), early apoptotic (Annexin V-positive and PI-negative) or late apoptotic (Annexin V-positive and PI-positive). N = 3 independent replicates. d Bioluminescence imaging of luciferase expressing OACM5.1 C esophageal tumors isolated from esophageal tubes 48 h post treatment with PEIII mRNA LNPs delivered in foam or suspension. Tumor plugs from 5 independent replicates are shown. e Summary plots showing differences in anti-tumor activity (luciferase signals). Pairwise difference between the groups were statistically analyzed using the unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t test. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Controls received no therapy. After 2 days, we removed the tumor plugs from the esophageal tube, submerged them in a solution containing D-Luciferin and quantitated tumor signals using an IVIS® instrument. We found that LNP suspensions achieved a modest 3.65-fold tumor reduction (Fig. 4d, e). This tumor-killing effect was greatly amplified by an average 110-fold, when delivering LNPs in foam instead of suspension, resulting in almost complete tumor clearance (Fig. 4d, e).

Gene therapy foam treatments make radiation therapy of EC more effective

Image-guided radiation therapy has become an important treatment option for patients with EC [27]; however, resistance leads to treatment failure and cancer relapse [28]. Based on the strong anti-tumor activity we achieved with gene therapy foam, we hypothesized that preconditioning EC with foam can enhance the lethal effect of radiation on cancer cells. To test this hypothesis, we first increased the number of OACM5.1 C esophageal carcinoma cells in tumor plugs of our test system threefold. This step was necessary as we noticed almost complete tumor clearance following gene therapy foam treatment (Fig. 4d, e). Residual tumor, however, is essential to evaluate if radiation acts synergistically with gene therapy foam. As a second step, we determined the optimal radiation dose, using a 137Cs irradiator. We found that exposing tumor plugs to a 50 Gy radiation dose was optimal, as it strongly reduced tumor viability by ~50%, again leaving room for potential synergistic effects between the two tested treatment modalities. To measure the therapeutic advantage of combining therapy, we treated EC tumor lesions either with radiation alone or preconditioned esophageal tubes with PEIII gene therapy foam one day prior to irradiation (depicted in Fig. 5a). Controls received no therapy. Using bioluminescence imaging, we established that radiation treatment reduced EC tumor burden 1.85-fold (P = 0.00156). This anti-tumor effect was further amplified 30.8-fold by pretreatment with gene therapy foam (Fig. 5b, c).

a Experimental schedule to measure the therapeutic benefit of combining gene therapy foam with radiation therapy. The number of OACM5.1 C esophageal carcinoma cells in tumor plugs of our test system was threefold higher, compared to experiments in Figs. 2–4. b Bioluminescence imaging of luciferase expressing OACM5.1 C esophageal tumors isolated from esophageal tubes post treatment. Tumor plugs from 5 independent replicates are shown. c Summary plots showing differences in anti-tumor activity (luciferase signals). Pairwise difference between the groups were statistically analyzed using the unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t test. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Discussion

Esophageal cancer is an aggressive disease for which current treatment modalities have limited success. With the first wave of gene-correcting drugs reaching the market and interest in gene therapy medicines on the rise [29,30,31], gene therapy could potentially also become a game-changing treatment for esophageal malignancies. Here, we developed a methylcellulose/xanthan gum-based foam that is stable and can be given orally so that it coats the esophagus and accumulates the gene therapy drug at the tumorous esophageal stricture as a novel cancer therapeutic for patients diagnosed with this aggressive tumor.

In stark contrast to current treatments (surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy), which require travel to specialized medical facilities and often lengthy hospital stays, gene therapy foam can be prepared and administered orally by a local family doctor or at home by the patient or caregiver. We believe that integrating gene therapy foam as a new treatment into the clinic can maximize the time esophageal cancer patients (and/or their family members, who are often the primary caregivers) can live normal lives outside of the hospital. Also, being able to work can significantly increase cancer patients’ quality of life [32]. We also hope that our treatment will allow patients to maintain their ability to swallow and eat and avoid tube feeding. Relying on a feeding tube is not only debilitating and depressing, but also often produces life-threatening infections [33,34,35]. Besides esophageal cancer, this foam technology could easily be adapted to treat other constricting cancer types, for instance advanced rectal cancer, as illustrated in Fig. 6, which is hard to treat [36]. Applying gene therapy foam with anti-cancer activity rectally could save patients from complicated and painful surgery and rounds of chemotherapy.

Schematic illustration the envisioned clinical workflow for rectally applying gene therapy foam in patients with locally advanced rectal cancer.

While the in vitro esophageal tumor model we used is an incredibly valuable tool for testing our new foam technology (Fig. 2), it cannot fully replicate all aspects of the natural esophagus’s intricate structure, peristalsis, and mucosal lining. We realize that, while we modeled flow and chemical composition of saliva and succeeded in epithelializing the inner surface of a tube with mucus secreting cells, we could not simulate the contraction and relaxation of the esophagus muscles. Several bioengineering teams have developed an artificial esophagus with peristaltic movement—often with the use of nickel-titanium shape memory alloy (NiTi-SMA) actuator placed around a Gore-Tex vascular graft [37, 38]. However, the complexity of these artificial esophagi and their associated experimental setups would have made cost-effective, high-throughput testing of gene therapy foam impossible for us. Extensive studies in large animal models will ultimately be essential to assess the safety and efficacy of orally applied gene therapy foam for the treatment of obstructive EC and bridge the gap between our preclinical research and clinical translation. In particular, dogs and pigs have been used extensively to study esophageal disease, with similarities in disease pathophysiology more similar to human beings than that of rodents [39]. For example, in a chronic model of acid reflux disease, the dog develops a phenotype of esophageal adenocarcinoma that faithfully recapitulates human disease [40]. These studies will likely depend on industry partners, given their high costs and the need for extensive veterinary medical care.

Many genes have been discovered that cause cancerous cells to die or slow their growth [41,42,43,44]. Our decision to overexpress the Pseudomonas exotoxin A catalytic domain was primarily guided by reports describing its fast and potent cytotoxicity against a variety of cancer cell lines [25, 26]. This helped us achieve fast readouts within 24-48 hours post treatment. Keeping our in vitro esophageal tumor test system continuously running for longer would have been technically challenging and prone to failure. We initially also considered other gene therapy candidates for inducing apoptosis in EC cells, such as SMAC (second mitochondria-derived activator of caspase [45]) and TRAIL (tumor-necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand [46]). TRAIL is a promising anti-cancer gene therapy due to its selective killing of cancer cells, sparing the vital normal cells [47]. However, its mechanism of action is not as potent as Pseudomonas exotoxin A, thus likely requiring frequent gene therapy foam redosing over weeks to achieve therapeutic effect, which is not compatible with our in vitro test system.

In summary, our findings establish that foam can substantially improve the therapeutic potential of EC gene therapy. Combining it with radiotherapy can increase the sensitivity of EC to radiation. Incorporated into the clinical workflow, this platform could help translate gene therapy into a standard treatment for EC, shifting the focus from indiscriminate chemotherapy and radical surgery to tumor-specific genetic modification.

Methods

Cell lines and culture media

The human epithelial cell line HT29-MTX-E12 and the human OACM5.1 C esophageal carcinoma cell line were obtained from MilliporeSigma (Cat# 12040401 and Cat# 11012006, respectively). For therapeutic studies that involve bioluminescent tumor imaging, OACM5.1 C cells were lentivirally transduced with firefly luciferase (F-luc). HT29-MTX-E12 cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) containing 2 mM l-glutamine, 1% non-essential amino acids, 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 U/mL streptomycin. OACM5.1 C cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium containing 2 mM l-glutamine, 10% FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 U/mL streptomycin. Cells were cultured in a humidified incubator at 5% (v/v) CO2. All cells tested negative for mycoplasma using a DNA-based PCR test.

mRNA synthesis

The reporter gene mRNA CleanCap® FLuc (Cat# L-7202-5) was purchased from TriLink Biotechnologies (San Diego, CA). MRNA encoding the third domain, also known as the catalytic domain, of Pseudomonas exotoxin A (PEIII) was custom-synthesized by Trilink Biotechnologies, according to the sequence shown below, with a 5-Methoxyuridine modification and a Cleancap M6.

PE domain III cDNA sequence used for IVT mRNA synthesis: ATGgccgaagaagctttcctcggcgacggcggcgacgtcagcttcagcacccgcggcacgcagaactggacggtgg agcggctgctccaggcgcaccgccaactggaggagcgcggctatgtgttcgtcggctaccacggcaccttcctcgaagc ggcgcaaagcatcgtcttcggcggggtgcgcgcgcgcagccaggacctcgacgcgatctggcgcggtttctatatcgcc ggcgatccggcgctggcctacggctacgcccaggaccaggaacccgacgcacgcggccggatccgcaacggtgccct gctgcgggtctatgtgccgcgctcgagcctgccgggcttctaccgcaccagcctgaccctggccgcgccggaggcggc gggcgaggtcgaacggctgatcggccatccgctgccgctgcgcctggacgccatcaccggccccgaggaggaaggcg ggcgcctggagaccattctcggctggccgctggccgagcgcaccgtggtgattccctcggcgatccccaccgacccgcg caacgtcggcggcgacctcgacccgtccagcatccccgacaaggaacaggcgatcagcgccctgccggactacgcca gccagcccggcaaaccgccgcgcgaggacctgaagTAA

Lipid nanoparticle (LNP) preparation

Lipid nanoparticles were prepared using a previously described method with minor modifications [48]. The ionizable lipid SM-102 was purchased from BroadPharm® (San Diego, CA). DSPC and DMG-PEG2000 lipids were both purchased from Avanti Research (Alabaster, AL). Cholesterol was purchased from Millipore Sigma. Lipids were dissolved in ethanol at a molar ratio of 50:10:38.5:1.5 (SM-102: DSPC: cholesterol: DMG-PEG2000). MRNA was diluted with 6.25 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 5) to 0.1 mg/mL. MRNA and lipids were combined in a Dolomite micromixer chip at a volume ratio of 3:1 (aqueous:ethanol) and flow rates of 4.5 mL/min (aqueous) and 1.5 mL/min (ethanol). The buffer of the resulting formulation was exchanged to PBS using Amicon Ultra centrifugal filters (100 K NMWL). More specifically, 0.9 mL LNPs were diluted with 1.1 mL PBS then concentrated to ~300 μL in the Amicon filter. This process was repeated 3 more times to bring the EtOH concentration down to 0.025%.

Foam preparation

Methylcellulose HV and xanthan gum were obtained from Modernist Pantry. Methylcellulose (80 mg) and xanthan gum (50 mg) were dissolved in 10 mL PBS to produce the foam precursor. To create the LNP/foam mixture, LNP suspension (200 μL containing 20 μg mRNA) was added to 1 mL of the foam precursor, then mixed with 9 mL of air via 30 passes between two 10-mL syringes connected at 90° with a 3-way Luer adapter (to create ~4 mL of foam).

In vitro esophageal carcinoma model

Cell seeding on collagen plugs

A fragment was trimmed from two collagen plugs (DSI Dental, Pure Sponge Big Plug, 10 × 20 mm) to form a flat surface. Each plug was placed in a well of a 6-well plate with the flat side facing down. A suspension containing 2.5 × 106 OACM5.1 cells was added to each plug and incubated at 37 °C for 10 min before adding 6 mL culture media to each well. The seeded plugs were incubated for 19 days before use, with media exchanged every 3 days. For radiation treatment experiments, a suspension containing 7.5 × 106 luc+ OACM5.1 cells was added to each plug.

Assembly of esophagus unit

5 mL of poly-L-lysine was added to a cell culture tube (Sarstedt, 125 × 16 mm), then incubated at 37 °C with rotation for 3 h. After rinsing the coated tube twice with water, 3 mL of a suspension of HT29-MTX-E12 cells (800,000 cells/mL) was added. The tube was capped loosely then rotated in an incubator for 2 days to achieve ~80% confluency. Media was aspirated from the cell-coated tube, then the closed end was removed using a pipe cutter. The OACM5.1-embedded plugs were affixed to the inside bottom of the culture tube using tissue adhesive, oriented with the flat sides facing the walls of the tube and the rounded end of the plugs pointing up. A 15 mL funnel was attached to the upper opening of the uncapped tube, and the complete unit was placed in a tissue culture incubator.

Artificial saliva flow

Four 140-mL syringes were filled to 40 mL with artificial saliva solution (RPMI + 10% FBS + 2% pen/strep + 0.1% mucin Type III) then fitted with a 100-cm length of 1.1 mm ID Tygon peristaltic pump tubing. The ends of the tubing were clipped to the top of the esophagus unit funnel with even spacing. Liquid flow was controlled using a Harvard Apparatus PHD ULTRA syringe pump programmed to dispense 120 µL/s per syringe with 1 min breaks between each infusion, yielding 28.8 mL/hr total flow rate.

Transfection with LNPs in foam or suspension

1 mL of the foam precursor was transferred to a 10-mL syringe, followed by LNPs carrying luciferase mRNA (200 μL containing 20 μg mRNA). Using a 3-way Luer adapter, the filled syringe was connected at 90° to a second 10-mL syringe containing 9 mL of air. The contents of the syringes were passed back and forth 30 times to create ~4 mL of foam. After 5 min of artificial saliva flow through the esophagus unit, the LNP-containing foam was dispensed into the top of the tube through an 18 G needle. Alternatively, LNPs were suspended in 4 mL PBS and dispensed into the top to the tube. Liquid flow was continued for 4 h, then the plugs were removed from the tube and transferred to a 6-well plate containing 6 mL OACM5.1 culture media per well. The tube was placed in a 50-mL tube filled with HT29-MTX-E12 culture media. The tube and plugs were incubated at 37 °C for 1 day before measuring bioluminescence.

Time lapse recordings

To track foam or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) suspension, we added UV-reactive Black Light Pigment (Neon, Brand: Glomania; purchased from Amazon.com) to the methylcellulose/xanthan gum foam precursor solution or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Esophageal tubes were illuminated in the dark with two Led Black Light Bars (Brand: Greenic, 10 W; purchased from Amazon.com) and time-lapse videos were recorded using a Panasonic® DC-Zs200D camera. The resulting images were viewed and light intensities in defined regions of interest (ROI) were quantitated using ImageJ (Version 1.53t).

Flow cytometry

To distinguish live, dead, and apoptotic tumor cells by flow cytometry, we stained cells using a commercially available Annexin-V-FITC/PI kit (ThermoFisher, Cat# V13242), according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Data was acquired using a BD FACSymphony™ A3 Cell Analyzer (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ) and analysis was performed using FlowJo v10.8.2 software (BD Biosciences).

Light microscopy

Light microscopy images were acquired using the Accu-Scope 3000-LED microscope (Microscope Central) with an attached View4K High-Definition Digital Microscope Camera (Microscope Central). An Alcian Blue (pH 2.5) Stain Kit (Vector Laboratories, Cat# H-3501) was used to visualize cell-secreted mucus. Neutral Red staining solution was purchased from Millipore Sigma (Cat# N6264).

Bioluminescence imaging

We used IVISbrite D-Luciferin (Revvity, Cat# 122799) in PBS (1 mg/ml) as a substrate for Firefly luciferase to measure gene transfer or esophageal tumor burden.

Bioluminescence images were collected with a Xenogen IVIS Spectrum Imaging System (Perkin Elmer). Living Image software version 4.8.2 (Revvity) was used to acquire (and later quantitate) the data.

Irradiation

For tumor irradiation experiments, tumor plugs were irradiated with 137Cs (50 Gy dose) using the Gammacell 1000 Elite instrument (MDS Nordion).

Statistics & reproducibility

The statistical significance of observed differences was analyzed using an unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t test. The P values for each measurement are listed in the figures or mentioned in the main text. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software version 10.4.1. No statistical method was used to predetermine sample size. No data were excluded from the analyses. The Investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessment.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary information files and directly from M. Stephan upon reasonable request.

References

-

Wang Y, Mukkamalla SKR, Singh R, Lyons, S. Esophageal cancer. in StatPearls (Treasure Island (FL), 2025).

-

Mohapatra S, Santharaman A, Gomez K, Pannala R, Kachaamy T. Optimal management of dysphagia in patients with inoperable esophageal cancer: current perspectives. Cancer Manag Res. 2022;14:3281–91.

-

Monig S, van Hootegem S, Chevallay M, Wijnhoven BPL. The role of surgery in advanced disease for esophageal and junctional cancer. Best Pr Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2018;36-37:91–96.

-

Wong LY, Elliott IA, Liou DZ, Backhus LM, Lui NS, Shrager JB, et al. The impact of refusing esophagectomy for treatment of locally advanced esophageal adenocarcinoma. JTCVS Open. 2023;16:987–95.

-

Xing XZ, Wang HJ, Qu SN, Huang CL, Zhang H, Wang H, et al. The value of esophagectomy surgical apgar score (eSAS) in predicting the risk of major morbidity after open esophagectomy. J Thorac Dis. 2016;8:1780–7.

-

Guyer DL, Almhanna K, McKee KY. Palliative care for patients with esophageal cancer: a narrative review. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8:1103.

-

Agrawal NY, Thawani R, Edmondson CP, Chen EY. Estimating the time toxicity of contemporary systemic treatment regimens for advanced esophageal and gastric cancers. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15:5677.

-

Fowler ME, Kenzik KM, Al-Obaidi M, Harmon C, Giri S, Arora S, et al. Rural-urban disparities in mortality and geriatric assessment among older adults with cancer: The cancer & aging resilience evaluation (CARE) registry. J Geriatr Oncol. 2023;14:101505.

-

Fitzgerald K, Stephan SB, Ma N, Wu QV, Stephan MT. Liquid foam improves potency and safety of gene therapy vectors. Nat Commun. 2024;15:4523.

-

Sharma AK, Giri AK. Engineering CRISPR/Cas9 therapeutics for cancer precision medicine. Front Genet. 2024;15:1309175.

-

Kaliberov SA, Buchsbaum DJ. Chapter seven-Cancer treatment with gene therapy and radiation therapy. Adv Cancer Res. 2012;115:221–63.

-

Liu Y, Hu X, Han C, Wang L, Zhang X, He X, et al. Targeting tumor suppressor genes for cancer therapy. Bioessays. 2015;37:1277–86.

-

Zheng Y, Jia H, Wang P, Liu L, Chen Z, Xing X, et al. Silencing TRAIP suppresses cell proliferation and migration/invasion of triple negative breast cancer via RB-E2F signaling and EMT. Cancer Gene Ther. 2023;30:74–84.

-

Hao S, Inamdar VV, Sigmund EC, Zhang F, Stephan SB, Watson C, et al. BiTE secretion from in situ-programmed myeloid cells results in tumor-retained pharmacology. J Control Release. 2022;342:14–25.

-

Yang J, Zhu J, Sun J, Chen Y, Du Y, Tan Y, et al. Intratumoral delivered novel circular mRNA encoding cytokines for immune modulation and cancer therapy. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2022;30:184–97.

-

Nguyen QM, Dupre PF, Haute T, Montier T, d’Arbonneau F. Suicide gene strategies applied in ovarian cancer studies. Cancer Gene Ther. 2023;30:812–21.

-

Li T, Kang G, Wang T, Huang H. Tumor angiogenesis and anti-angiogenic gene therapy for cancer. Oncol Lett. 2018;16:687–702.

-

Mistarz A, Graczyk M, Winkler M, Singh PK, Cortes E, Miliotto A, et al. Induction of cell death in ovarian cancer cells by doxorubicin and oncolytic vaccinia virus is associated with CREB3L1 activation. Mol Ther Oncolytics. 2021;23:38–50.

-

Sang Q, Goyal RK. Lower esophageal sphincter relaxation and activation of medullary neurons by subdiaphragmatic vagal stimulation in the mouse. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:1600–9.

-

Pang J, Borjeson TM, Muthupalani S, Ducore RM, Carr CA, Feng Y, et al. Megaesophagus in a line of transgenic rats: a model of achalasia. Vet Pathol. 2014;51:1187–1200.

-

Iorgulescu G. Saliva between normal and pathological. Important factors in determining systemic and oral health. J Med Life. 2009;2:303–7.

-

Waqar MA, Mubarak N, Khan AM, Khan R, Shaheen F, Shabbir A. Advanced polymers and recent advancements on gastroretentive drug delivery system; a comprehensive review. J Drug Target. 2024;32:655–71.

-

Michalska M, Wolf P. Pseudomonas Exotoxin A: optimized by evolution for effective killing. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:963.

-

Havaei SM, Aucoin MG, Jahanian-Najafabadi A. Pseudomonas exotoxin-based immunotoxins: over three decades of efforts on targeting cancer cells with the toxin. Front Oncol. 2021;11:781800.

-

Granot-Matok Y, Ezra A, Ramishetti S, Sharma P, Naidu GS, Benhar I, et al. Lipid nanoparticles-loaded with toxin mRNA represents a new strategy for the treatment of solid tumors. Theranostics. 2023;13:3497–508.

-

Somu Naidu G, Rampado R, Sharma P, Ezra A, Kundoor GR, Breier D, et al. Ionizable lipids with optimized linkers enable lung-specific, lipid nanoparticle-mediated mRNA delivery for treatment of metastatic lung tumors. ACS Nano. 2025;19:6571–87.

-

Li CC, Chen CY, Chien CR. Comparative effectiveness of image-guided radiotherapy for non-operated localized esophageal squamous cell carcinoma patients receiving concurrent chemoradiotherapy: A population-based propensity score matched analysis. Oncotarget. 2016;7:71548–55.

-

Chen GZ, Zhu HC, Dai WS, Zeng XN, Luo JH, Sun XC. The mechanisms of radioresistance in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and current strategies in radiosensitivity. J Thorac Dis. 2017;9:849–59.

-

Jin, J & Zhong, XB ASO drug Qalsody (tofersen) targets amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2023;44:1043–4.

-

Mendell, JR, Sahenk, Z, Lehman, KJ, Lowes, LP, Reash, NF, Iammarino, MA, et al. Long-term safety and functional outcomes of delandistrogene moxeparvovec gene therapy in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy: a phase 1/2a nonrandomized trial. Muscle Nerve. 2024;69:93–8.

-

Darrow JJ. Luxturna: FDA documents reveal the value of a costly gene therapy. Drug Discov Today. 2019;24:949–54.

-

Blinder VS, Gany FM. Impact of cancer on employment. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:302–9.

-

Padilla GV, Grant MM. Psychosocial aspects of artificial feeding. Cancer. 1985;55:301–4.

-

Roberge C, Tran M, Massoud C, Poiree B, Duval N, Damecour E, et al. Quality of life and home enteral tube feeding: a French prospective study in patients with head and neck or oesophageal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2000;82:263–9.

-

Barrett D, Li V, Merrick S, Murugananthan A, Steed H. The hidden burden of community enteral feeding on the emergency department. JPEN J Parenter Enter Nutr. 2021;45:1347–51.

-

Smith JJ, Garcia-Aguilar J. Advances and challenges in treatment of locally advanced rectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:1797–808.

-

Watanabe M, Sekine K, Hori Y, Shiraishi Y, Maeda T, Honma D, et al. Artificial esophagus with peristaltic movement. ASAIO J. 2005;51:158–61.

-

Chung EJ. Bioartificial esophagus: where are we now?. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2018;1064:313–32.

-

Martinez-Uribe O, Becker TC, Garman KS. Promises and limitations of current models for understanding barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;17:1025–38.

-

Kapoor H, Lohani KR, Lee TH, Agrawal DK, Mittal SK. Animal models of Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma-past, present, and future. Clin Transl Sci. 2015;8:841–7.

-

Peng Y, Bai J, Li W, Su Z, Cheng X. Advancements in p53-based anti-tumor gene therapy research. Molecules. 2024;29:5315.

-

Meraz IM, Majidi M, Song R, Meng F, Gao L, Wang Q, et al. NPRL2 gene therapy induces effective antitumor immunity in KRAS/STK11 mutant anti-PD1 resistant metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) in a humanized mouse model. Elife. 2025;13:RP98258.

-

Dakal TC, Dhabhai B, Pant A, Moar K, Chaudhary K, Yadav V, et al. Oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes: functions and roles in cancers. MedComm (2020). 2024;5:e582.

-

Abou Madawi NA, Darwish ZE, Omar EM. Targeted gene therapy for cancer: the impact of microRNA multipotentiality. Med Oncol. 2024;41:214.

-

Li W, Turaga RC, Li X, Sharma M, Enadi Z, Dunham Tompkins SN, et al. Overexpression of smac by an armed vesicular stomatitis virus overcomes tumor resistance. Mol Ther Oncolytics. 2019;14:188–95.

-

Zhong HH, Wang HY, Li J, Huang YZ. TRAIL-based gene delivery and therapeutic strategies. Acta Pharm Sin. 2019;40:1373–85.

-

Montinaro A, Walczak H. Harnessing TRAIL-induced cell death for cancer therapy: a long walk with thrilling discoveries. Cell Death Differ. 2023;30:237–49.

-

Sabnis S, Kumarasinghe ES, Salerno T, Mihai C, Ketova T, Senn JJ, et al. A novel amino lipid series for mRNA delivery: improved endosomal escape and sustained pharmacology and safety in non-human primates. Mol Ther. 2018;26:1509–19.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the Fred Hutch Immunotherapy Initiative with funds provided by the Bezos Family Foundation.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

MTS is co-founder of, and has received stock options from Persistence Therapeutics (Jupiter Bioventures); he has IP Licensing with Sanofi, Juno Therapeutics (now Bristol Myers Squibb), and Jupiter Bioventures. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics declarations

This study was conducted exclusively in vitro; therefore obtaining IACUC approval was not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Stephan, S.B., Cummings, C.L., Fitzgerald, K. et al. Drinkable gene therapy foam for the treatment of constrictive esophageal carcinoma. Gene Ther (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41434-026-00592-7

-

Received:

-

Revised:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

Version of record:

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41434-026-00592-7