Data availability

All data that support the findings of this study are available in the article and Supplementary Information. The codon-optimized sequence of the pine longifolene synthase TPS was deposited in GenBank (accession number OQ242380). Source data are provided with this paper.

References

-

World Malaria Report (World Health Organization, 2024); https://www.who.int/teams/global-malaria-programme/reports/world-malaria-report-2024

-

Farenhorst, M. et al. Fungal infection counters insecticide resistance in African malaria mosquitoes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 17443–17447 (2009).

-

Bilgo, E. et al. Improved efficacy of an arthropod toxin expressing fungus against insecticide-resistant malaria-vector mosquitoes. Sci. Rep. 7, 3433 (2017).

-

Lovett, B. et al. Transgenic Metarhizium rapidly kills mosquitoes in a malaria-endemic region of Burkina Faso. Science 364, 894–897 (2019).

-

Barrera, R. New tools for Aedes control: mass trapping. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 52, 100942 (2022).

-

Lwetoijera, D. W. et al. An extra-domiciliary method of delivering entomopathogenic fungus, Metarhizium anisopliae IP 46 for controlling adult populations of the malaria vector, Anopheles arabiensis. Parasit. Vectors 3, 18 (2010).

-

Angelone, S., Piña-Torres, I. H., Padilla-Guerrero, I. E. & Bidochka, M. J. “Sleepers” and “Creepers”: a theoretical study of colony polymorphisms in the fungus Metarhizium related to insect pathogenicity and plant rhizosphere colonization. Insects 9, 104 (2018).

-

George, J., Jenkins, N. E., Blanford, S., Thomas, M. B. & Baker, T. C. Malaria mosquitoes attracted by fatal fungus. PLoS ONE 8, e62632 (2013).

-

St. Leger, R. J. & Wang, J. B. Metarhizium: jack of all trades, master of many. Open Biol. 10, 200307 (2020).

-

Kant, M. R., Ament, K., Sabelis, M. W., Haring, M. A. & Schuurink, R. C. Differential timing of spider mite-induced direct and indirect defenses in tomato plants. Plant Physiol. 135, 483–495 (2004).

-

Morteza-Semnani, K., Saeedi, M. & Akbarzadeh, M. Essential oil composition of Teucrium scordium L. Acta Pharm. 57, 499–504 (2007).

-

Larsson, M. C. et al. Or83b encodes a broadly expressed odorant receptor essential for Drosophila olfaction. Neuron 43, 703–714 (2004).

-

Sweeney, S. T., Broadie, K., Keane, J., Niemann, H. & O’Kane, C. J. Targeted expression of tetanus toxin light chain in Drosophila specifically eliminates synaptic transmission and causes behavioral defects. Neuron 14, 341–351 (1995).

-

Elmore, T., Ignell, R., Carlson, J. R. & Smith, D. P. Targeted mutation of a Drosophila odor receptor defines receptor requirement in a novel class of sensillum. J. Neurosci. 23, 9906–9912. (2003).

-

Takken, W. & Knols, B. G. J. Odor-mediated behavior of Afrotropical malaria mosquitoes. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 44, 131–157 (1999).

-

Paixão, F. R. S. et al. Pathogenicity of microsclerotia from Metarhizium robertsii against Aedes aegypti larvae and antimicrobial peptides expression by mosquitoes during fungal–host interaction. Acta Trop. 249, 107061 (2024).

-

Hassan, J. et al. Engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae for the de novo synthesis of the aroma compound longifolene. Chem. Eng. Sci. 226, 115799 (2020).

-

Gao, Q. et al. Genome sequencing and comparative transcriptomics of the model entomopathogenic fungi Metarhizium anisopliae and M. acridum. PLoS Genet. 7, e1001264 (2011).

-

Lovett, B. et al. Behavioral betrayal: how select fungal parasites enlist living insects to do their bidding. PLoS Pathog. 16, e1008598 (2020).

-

de Bekker, C., Beckerson, W. C. & Elya, C. Mechanisms behind the madness: how do zombie-making fungal entomopathogens affect host behavior to increase transmission? mBio 12, e0187221 (2021).

-

Brancini, G. T. P., Hallsworth, J. E., Corrochano, L. M. & Braga, G. Ú. L. Photobiology of the keystone genus Metarhizium. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 226, 112374 (2022).

-

Behie, S. W., Zelisko, P. M. & Bidochka, M. J. Endophytic insect-parasitic fungi translocate nitrogen directly from insects to plants. Science 336, 1576–1577 (2012).

-

Melo, N. et al. Geosmin attracts Aedes aegypti mosquitoes to oviposition sites. Curr. Biol. 30, 127–134 (2020).

-

Stensmyr, M. C. et al. A conserved dedicated olfactory circuit for detecting harmful microbes in Drosophila. Cell 151, 1345–1357 (2012).

-

Hallem, E. A., Ho, M. G. & Carlson, J. R. The molecular basis of odor coding in the Drosophila antenna. Cell 117, 965–979 (2004).

-

Wang, Q. et al. Identification of multiple odorant receptors essential for pyrethrum repellency in Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS Genet. 17, e1009677 (2021).

-

Kreher, S. A., Kwon, J. Y. & Carlson, J. R. The molecular basis of odor coding in the Drosophila larva. Neuron 46, 445–456 (2005).

-

Marshall, B., Warr, C. G. & de Bruyne, M. Detection of volatile indicators of illicit substances by the olfactory receptors of Drosophila melanogaster. Chem. Senses 35, 613–625 (2010).

-

Konopka, J. K. et al. Olfaction in Anopheles mosquitoes. Chem. Senses 46, bjab021 (2021).

-

Tusting, L. S. et al. Housing improvements and malaria risk in sub-Saharan Africa: a multi-country analysis of survey data. PLoS Med. 14, e1002234 (2017).

-

Guidelines for Efficacy Testing of Spatial Repellents WHO/HTM/NTD/WHOPES/2013 (World Health Organization, 2013).

-

Moonjely, S. & Bidochka, M. J. Generalist and specialist Metarhizium insect pathogens retain ancestral ability to colonize plant roots. Fungal Ecol. 41, 209–217 (2019).

-

Wang, J. B., Lu, H. L., Sheng, H. & St. Leger, R. J. A Drosophila melanogaster model shows that fast growing Metarhizium species are the deadliest despite eliciting a strong immune response. Virulence 14, 2275493 (2023).

-

Ngugi, H. K. & Scherm, H. Mimicry in plant-parasitic fungi. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 257, 171–176 (2006).

-

Pull, C. D. et al. Destructive disinfection of infected brood prevents systemic disease spread in ant colonies. eLife 7, e32073 (2018).

-

Api, A. M. et al. RIFM fragrance ingredient safety assessment, longifolene, CAS Registry Number 475-20-7. Food Chem. Toxicol. 134, 110823 (2019).

-

Mukai, A., Takahashi, K. & Ashitani, T. Antifungal activity of longifolene and its autoxidation products. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 76, 1079–1082 (2018).

-

Ryabchenko, B. et al. Investigation of anticancer and antiviral properties of selected aroma samples. Nat. Prod. Commun. 3, 1085–1088 (2008).

-

Schmidt, E. et al. Antimicrobial activities of single aroma compounds. Nat. Prod. Commun. 5, 1365–1368 (2010).

-

Tsuruta, K. et al. Inhibition activity of essential oils obtained from Japanese trees against Skeletonema costatum. J. Wood Sci. 57, 520–525 (2011).

-

Fang, W. & St. Leger, R. J. Enhanced UV resistance and improved killing of malaria mosquitoes by photolyase transgenic entomopathogenic fungi. PLoS ONE 7, e43069 (2012).

-

Tang, X., Wang, X., Cheng, X., Wang, X. & Fang, W. Metarhizium fungi as plant symbionts. New Plant Prot. 2, e23 (2025).

-

Fang, W., Pei, Y. & Bidochka, M. J. Transformation of Metarhizium anisopliae mediated by Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Can. J. Microbiol. 52, 623–626 (2006).

-

Zhang, X., Meng, Y., Huang, Y., Zhang, D. & Fang, W. A novel cascade allows Metarhizium robertsii to distinguish cuticle and hemocoel microenvironments during infection of insects. PLoS Biol. 19, e3001360 (2021).

-

Rehner, S. A. Genetic structure of Metarhizium species in western USA: finite populations composed of divergent clonal lineages with limited evidence for recent recombination. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 177, 107491 (2020).

-

Tamura, K., Stecher, G., Peterson, D., Filipski, A. & Kumar, S. MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 2725–2729 (2013).

-

Ronquist, F. & Huelsenbeck, J. P. MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics 19, 1572–1574 (2003).

-

Huang, J. H., Reilein, A. & Kalderon, D. Yorkie and Hedgehog independently restrict BMP production in escort cells to permit germline differentiation in the Drosophila ovary. Development 144, 2584–2594 (2017).

-

Fishilevich, E. et al. Chemotaxis behavior mediated by single larval olfactory neurons in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 15, 2086–2096 (2005).

-

Dweck, H. K. M. et al. The olfactory logic behind fruit odor preferences in larval and adult Drosophila. Cell Rep. 23, 2524–2531 (2018).

-

Zhang, H. et al. A volatile from the skin microbiota of flavivirus-infected hosts promotes mosquito attractiveness. Cell 28, S0092-8674(22)00641-9 (2022).

-

Stökl, J. et al. A deceptive pollination system targeting drosophilids through olfactory mimicry of yeast. Curr. Biol. 20, 1846–1852 (2010).

-

Robinson, A. et al. Plasmodium-associated changes in human odor attract mosquitoes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, E4209–E4218 (2018).

-

Xu, Y. et al. Plant volatile organic compound (E)-2-hexenal facilitates Botrytis cinerea infection of fruits by inducing sulfate assimilation. New Phytol. 231, 432–446 (2021).

-

Babushok, V. I. Chromatographic retention indices in identification of chemical compounds. Trends Anal. Chem. 69, 98–104 (2015).

-

Song, H. et al. An inactivating mutation in the vacuolar arginine exporter gene Vae results in culture degeneration in the fungus Metarhizium robertsii. Environ. Microbiol. 24, 2924–2937 (2022).

-

Chen, Y. et al. Nitrogen-starvation triggers cellular accumulation of triacylglycerol in Metarhizium robertsii. Fungal Biol. 122, 410–419 (2018).

-

Guo, H. et al. Sex pheromone communication in an insect parasitoid, Campoletis chlorideae Uchida. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2215442119 (2022).

-

Pan, X. et al. Wolbachia induces reactive oxygen species (ROS)-dependent activation of the Toll pathway to control dengue virus in the mosquito Aedes aegypti. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, E23–E31 (2012).

-

Zhang, M. et al. Early attainment of 20-hydroxyecdysone threshold shapes mosquito sexual dimorphism in developmental timing. Nat. Commun. 16, 821 (2025).

-

Lahondère, C. A step-by-step guide to mosquito electroantennography. J. Vis. Exp. 169, e62042 (2021).

-

Xu, C. et al. A high-throughput gene disruption methodology for the entomopathogenic fungus Metarhizium robertsii. PLoS ONE 9, e107657 (2014).

-

Meng, Y. et al. A novel nitrogen and carbon metabolism regulatory cascade is implicated in entomopathogenicity of the fungus Metarhizium robertsii. mSystems 6, e0049921 (2021).

-

Brogdon, W. G. & Chan, A. Guideline for Evaluating Insecticide Resistance in Vectors Using the CDC Bottle Bioassay (US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2010); https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/21777

-

Bayili, K. Laboratory and experimental hut trial evaluation of VECTRONTM T500 for indoor residual spraying (IRS) against insecticide resistant malaria vectors in Burkina Faso. Gates Open Res. 6, 57 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We thank M. Jiang and X. Wang from the Institute of Insect Science at Zhejiang University for providing experimental insects. We thank Y. Chen and Y. Xu at Zhejiang University for help with SPME–GC–MS analysis, D. Lou at Zhejiang University for help with video recording and X. Deng at Nanjing Medical University for help with statistical analysis. We recognize the indispensable efforts of undergraduate students at Zhejiang University involved in this study (H. Jiang, Y. Yang and J. Liu). This work was funded by grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China to W.F. (82261128002, 32172470) and to J. Huang (32325044), Gates Foundation (INV-070892) and ‘Pioneer’ and ‘Leading Goose’ R&D Program of Zhejiang (2023C02025) to W.F., and National Key R&D Program of China (number 2023YFA1801004) to J. Cao.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

D.T. and W.F. filed a patent application (Chinese Patent application no. 202210069879.X, published April 27, 2022). The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Microbiology thanks Marcio Cortes, Olaf Kniemeyer, Patil Tawidian and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

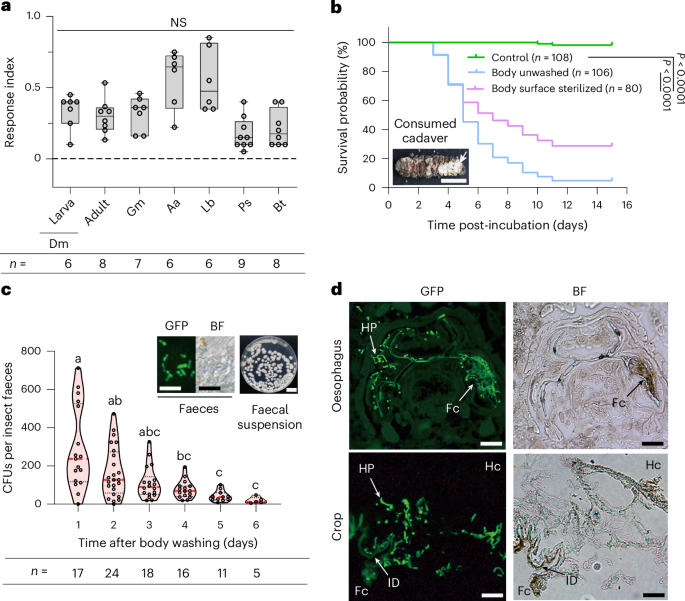

Extended Data Fig. 1 M. robertsii-colonized G. mellonella larval cadavers attract healthy insects to become infected.

(a) G. mellonella larva mycosed by the GFP-expressing M. robertsii strain WT-GFP visualized with bright field (BF, Left, scale bar: 0.5 cm), and epifluorescence using filters set to detect GFP fluorescence (GFP, Middle). WT-GFP spores on the cadaver (Right, scale bar: 10 μm). Healthy larvae used as controls for autofluorescence. (b) Healthy 3rd instar D. melanogaster larvae were infected after attraction to M. robertsii-colonized G. mellonella cadavers. Left panel: WT-GFP CFUs per larval surface after 10 min exposure to cadavers. Right panel: insects after exposure to cadavers (top: healthy larvae as a control for autofluorescence; middle: dark green spores (arrowed) in guts just post-exposure; bottom: a WT-GFP-colonized D. melanogaster cadaver five days post-exposure). Scale bar: 0.1 cm. N: the number of insects assayed. (c) Spores attached to the cuticle of healthy G. mellonella larvae after 30 min exposure to M. robertsii-colonized G. mellonella cadavers. Left: WT-GFP CFUs per larval surface. Right: spores and fungal growth on larval cuticle [top: spores attached to intersegmental membranes after body surface sterilization (scale bar: 50 μm); middle: excised cuticle from sterilized insect placed on Metarhizium-selective medium (note: no fungal growth); bottom: fungal growth on excised cuticle from unwashed insects (scale bar: 1 cm)]. (d) Ingested spores in the alimentary canals of healthy G. mellonella larvae at different time points after 30 min exposure to WT-GFP-colonized G. mellonella cadavers. This figure supplement Fig. 1d. Note: ingested spores can infect healthy larvae by penetrating foreguts. S: spores; GL: fungal germlings; HP: fungal hyphae; H: insect hemocytes. ID: intima dentation in foregut crops; Hb: yeast-like hyphal bodies (blastospores) of the fungus. Scale bar: 50 μm. Images are representative of at least three independent experiments.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Two-way choice assays of the response to longifolene (10−5 g) (versus hexane) of larvae of the WT (wild type), deficiency lines of 19 larval ORs (constructed with the Or-GAL4/UAS-TNT system), and their respective controls.

Response index was calculated as (O-C)/T, where O was the number of larvae in the longifolene zone, C was the number in the hexane (control) zone, and T was the total number of larvae assayed. The box plots show the median (center line), the interquartile range (box bounds, 25th to 75th percentiles), and the whiskers (minima and maxima within 1.5 × interquartile range from the box). n.s: not significantly different (P > 0.05, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test, n = 10). Data about two other larval deficient lines (Or43b and Or74a) are shown in Fig. 3b. Note: data about WT, UAS-TNT, WT×UAS-TNT are also shown in Fig. 3b for convenient comparison.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Generation of the Or43b and Or74 mutant using CRISPR/Cas9-based gene editing.

Upper panel: Or43b mutant Or43bI4 with four base pairs (highlighted in red) inserted into Exon 1. Lower panel: Or74a mutant Or74aD31 with 31 base pairs deleted (shown in dashed line) in the Exon 1.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Expression profiles of Or43b and Or74a in D. melanogaster.

(a) RT-PCR analysis of Or43b and Or74a expression in larvae and adult antennae. Larva: total RNA from the most anterior part of the larvae, containing dorsal organ; Adult: total RNA from antennae. M: DNA ladder. Actin5C: reference gene. (b) Determination of the expression of Or43b and Or74a in larvae via observation of mRFP in a single symmetric pair of larval ORNs (Arrowed), one in each dorsal organ in larvae with mRFP expression driven by Or43b-GAL4 (genotype: Or43b > mCD8-RFP) (Upper panel) and Or74a-GAL4 (genotype: Or74a > mCD8-RFP) (Lower panel). The most anterior part of Drosophila larva outlined with white dash line. Scale bars: 20 μm. Images are representative of three independent experiments.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Phylogenetic analyses identifying the Metarhizium isolate used in this study as M. pingshaense and the wild-caught mosquitoes as Ae. albopictus.

(a) Analysis of M. pingshaense TM1 strain (bold) compared to previously determined Metarhizium species using the 5′TEF sequences. The 5′TEF sequence from the TM1 strain is shown in Supplementary Table 2. (b) Analysis of three randomly selected wild-caught male and female mosquitoes compared to previously determined Aedes species using the Mt-COI gene. The GenBank accession number for each sequence from a previously determined species is shown. Numbers at nodes represent the bootstrap values from Neighbor-Joining (left), Maximum Likelihood (middle), and Bayesian posterior probabilities (right). A hyphen (-) indicates no support for the given node in the corresponding method. The scale bar corresponds to the estimated number of nucleotide substitutions per site.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Construction of transgenic M. robertsii strain Mr-Tps expressing the pine longifolene synthase gene Tps driven by the constitutive Aureobasidium pullulans promoter Ptef.

(a) RT-PCR confirmation of Tps expression in M. robertsii. M: DNA ladder. Tef: reference gene encoding translation elongation factor. WT: the parental WT strain of Mr-Tps. Images are representative of three independent experiments. (b) Spore yield on the PDA. Experiment repeated three times with four replicates per repeat. Two-tailed Student’s t-test was used [also used in c in this figure n = 12 (b) and n = 3 (c)]. Data presented as mean ± SE. (c) Pathogenicity against G. mellonella larvae infected with 3 × 107 spores/mL. Data presented as mean ± SE. (d) Flow cytometry assays of spore lipid droplets stained with BODIPY dye. Inset: representative stained spores (of over 100 spores). Scale bar: 5μm. Note: no obvious difference between Mr and Mr-Tps. (e) Kaplan-Meier curves of survival of Ae. albopictus adults after being sprayed with Mr-Tps spore suspensions (107 spores/mL). Log-rank test was used (N: the number of insects assayed). (f) Emission of longifolene by lipid droplets from 12-day M. robertsii-colonized G. mellonella cadavers, sporulated mycelia from the cadavers, PDA and BRH cultures. Values represent fold changes in emission amount of longifolene by Mr-Tps compared to the WT. Data presented as mean ± SE. (g) Behavioral preferences of Ae. albopictus adult female mosquitoes (two-port olfactometer assay) and D. melanogaster larvae (two-choice assay) for the WT and Mr-Tps spores on mycosed G. mellonella cadavers, PDA and BRH. Behavioral preference was shown as the percentage of insects in either stimulus zone out of the total of insects that had made a choice, which was calculated as N1or N2/(N1 + N2), where N1 was the number of insects in stimulus #1 zone, and N2 in stimulus #2 zone. Data presented as mean ± SE. Two-tailed Mann-Whitney test was used (n = 6).

Extended Data Fig. 7 Characterization of transgenic M. pingshaense strain Mp-Tps expressing pine longifolene synthase gene Tps.

(a) Spore yields on BRH (left) and PDA (right) media. Two-tailed Student’s t-test was used. Data presented as mean ± SE. WT: the parental WT strain of Mp-Tps. (b) Number of spores per adult mosquito (Ae. albopictus) after being sprayed with spore suspensions (105, 106 or 107 spores/mL). Horizontal line: medians. N: the number of mosquitoes assayed. Two-tailed Mann-Whitney test was used. (c) LT50 values for mosquitoes with inoculations described in (b). Two-tailed Student’s t-test was used (n = 3). Data presented as mean ± SE. For mortalities seven days post-inoculation, within each spore suspension, values with same letters are not significantly different (P values shown below, Two-tailed Student’s t-test, n = 3). (d) LD50 values for mosquitoes with inoculations described in (b). Two-tailed Student’s t-test was used (n = 3). Data presented as mean ± SE. (e) LT50 values for G. mellonella larvae following immersion in 3 × 107 spores/ml. Two-tailed Student’s t-test was used. Data presented as mean ± SE. (f) Longifolene and sativene-containing portions of GC-MS analysis of 50-, and single Mp-Tps or the WT colonized mosquito cadavers. Note: no longifolene detected in single Mp-Tps cadavers. (g) Behavioral preferences (single Mp-Tps-colonized mosquito cadavers versus freeze-killed mosquitoes) of adult Ae. albopictus mosquitoes and 3rd instar D. melanogaster larvae. Data presented as mean ± SE. Two-tailed Mann-Whitney test was used (n = 6). (h) A representative Mp-Tps-colonized mosquito cadaver (of over 30 cadavers) under bright field and epifluorescence using filters set to detect GFP fluorescence (GFP) (Left panel), and the number of spores on single cadavers (Right panel). N: the number of mosquitoes assayed. Scale bar: 2 mm.

Extended Data Fig. 8 The ability of M. pingshaense strains to attract and kill laboratory-reared adult Ae. albopictus mosquitoes in 1m3-cages.

(a) Males. (b) Females. WT: the parental WT strain of the transgenic strain Mp-Tps. Exposed to Mp-Tps or the WT BRH cultures for one (1 h), two (2 h) and 12 (12 h) hours. Left panel: inoculum load (Horizontal line: median) and inoculation rate. Right: LT50 values and mortality at day seven post-exposure. Data presented as mean ± SE. Within each figure, different capital letters (blue) indicate significant differences (P < 0.05) among all treatments. Different small letters (black) indicate significant differences in inoculum load and LT50 (P value given on the top) and inoculation rate and mortality (P values given below) between the WT and Mp-Tps following the same exposure period. For inoculum load, the two-tailed Mann-Whitney test was used for comparisons between two samples, and the Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test was used for multiple samples. For inoculation rate, LT50 values and mortality, two-tailed Student’s t-test for two samples and one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test for multiple samples. N: the total number of mosquitoes assayed; R: experiment repeats.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Differences in infection parameters and visitation to the fungal cultures between female and male mosquitoes.

(a) The inoculum load (Horizontal line: median) and inoculation rate. WT: the parental WT strain of the transgenic strain Mp-Tps. Within the same exposure period, different letters mean significant differences among all treatments (P < 0.05, The Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test). (b) LT50 values and mortality. Data presented as mean ± SE. Within the same exposure period, different letters mean significant differences among all treatments (P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test). a and b are other ways to illustrate the data presented in Extended Data Fig. 8. (c) Visitation to Mp-Tps or the WT BRH cultures (shown as the number of visits and the cumulative time spent on cultures within one hour exposure) and inoculum load during the visitation. Visitation and inoculum load of mosquitoes were individually assayed. Horizontal line: median. N: the number of mosquitoes assayed. Two-tailed Student’s t-test was used. (d) Correlations between inoculum load per mosquito (log transformation) and the number of visits to fungal cultures (Left) or the cumulative time spent on the cultures (Right). Upper panel: Mp-Tps cultures; Lower panel: the WT cultures. Calculations were conducted with the two-tailed Pearson’s correlation.

Extended Data Fig. 10 Impacts of human odors and mosquito-attracting flowering plants on the ability of Mp-Tps BRH cultures to attract and kill adult wild-caught Ae. albopictus in a large room.

This figure supplement Fig. 6. (a) Kaplan-Meier curves of survival of mosquitoes treated with the WT and Mp-Tps BRH cultures with or without human volunteers. Experiments repeated three to four times. Dashed lines represent 80% mortality (WHO control threshold for successful vector control agent). Mock: untreated mosquitoes; Human: mosquitoes treated with humans only; WT: BRH cultures of the WT strain only; Mp-Tps: Mp-Tps BRH cultures only; WT + Human: BRH cultures of the WT strain in presence of humans; Mp-Tps + Human: Mp-Tps BRH cultures in presence of humans; WT + Plant: BRH cultures of the WT strain in presence of plants; Mp-Tps + plant: Mp-Tps BRH cultures in presence of plants. Log-rank test was used (N: the number of mosquitoes assayed). (b) Two-port olfactometer assays of mosquito’s response to flowers, leaves, Mp-Tps and the WT BRH cultures. Left panel: plant tissues versus water-soaked cotton (control). The box plots show the median (center line), the interquartile range (box bounds, 25th to 75th percentiles), and the whiskers (minima and maxima within 1.5 × interquartile range from the box). Values with different letters are significantly different (P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test). Response index was calculated as (O-C)/T, where O was the number of mosquitoes in the plant tissue chamber, C was the number in the cotton chamber, and T was the total number of mosquitoes assayed. Middle panel: Mp-Tps or the WT BRH cultures versus flowers, and leaves (Right panel). Data presented as mean ± SE. Two-tailed Student’s t-test was used. Kaplan-Meier curves of survival of sugar fed (c), and (d) sugar-starved mosquitoes treated with Metarhizium cultures with or without plants.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–15, Supplementary Results, Supplementary Discussion, References and uncropped agarose gels for the supplementary figures.

Reporting Summary

Peer Review File

Supplementary Tables

Supplementary Tables 1–3.

Supplementary Video 1

Response of the WT D. melanogaster larvae (3rd instar) to 12-day M. robertsii-colonized G. mellonella larval cadavers (right in the Petri dish) versus freeze-killed healthy G. mellonella larvae (left in the Petri dish). The video is a representative of at least six independent experiments.

Supplementary Video 2

Response of D. melanogaster Orco2 larvae (3rd instar), lacking odorant coreceptor Orco, to 12-day M. robertsii-colonized larval cadavers (right in the Petri dish) versus freeze-killed healthy G. mellonella larvae (left in the Petri dish). The video is a representative of at least six independent experiments.

Supplementary Video 3

Female A. albopictus mosquitoes on Mp-Tps BRH cultures. The video is a representative of at least six independent experiments.

Supplementary Video 4

Male A. albopictus mosquitoes on Mp-Tps BRH cultures. The video is a representative of at least six independent experiments.

Supplementary Data 1

Mass spectrometry raw data and figures for longifolene, sativene and geosmin (standards and cadaver samples).

Supplementary Data 2

Written informed consent for human volunteers.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Tang, D., Chen, J., Zhang, Y. et al. Engineered Metarhizium fungi produce longifolene to attract and kill mosquitoes. Nat Microbiol (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-025-02155-9

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-025-02155-9