Introduction

The rise of antibiotic-resistant bacteria poses a significant threat to global health. It is estimated that in 2019, the number of deaths linked to antibiotic-resistant bacteria was 1.9 million1. What is even more alarming is that without effective countermeasures to mitigate this issue, by 2050, there will be 10 million deaths linked to antibiotic resistance2. Thus, identifying novel and innovative treatments and alternatives to antibiotics is imperative.

Targeted therapy, an approach that focuses on specific vulnerabilities of pathogens while minimizing collateral damage to host cells, emerges as a promising avenue in the battle against drug-resistant bacteria3. One of the key challenges of targeted therapy is the selective identification and exploitation of specific bacterial vulnerabilities. By specifically targeting pathogenic bacteria, these therapies may spare beneficial surrounding microbes, thereby reducing the risk of secondary infections and disturbances to the host’s physiological balance3.

Silver is a widely used metal for reducing bacterial growth without generating bacterial resistance4. Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) have garnered much attention for their physicochemical properties and remarkable antimicrobial effects against both gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria5,6,7. AgNPs have a large surface-to-volume ratio, which increases the amount of active silver surface available to be effective against microbes8. In light of this, AgNPs are used in a wide range of healthcare applications, including medical device coatings (e.g., coated contact lenses and medical catheters), personal care products (e.g., toothpaste), and personalized therapy and diagnostics9. However, the development of AgNPs for antimicrobial therapies has been hindered by their toxicity, which limits their use in treating systemic bacterial infections. AgNP-induced toxicity is influenced by several factors, including the concentration of the AgNPs, their exposure time, and their lack of specificity for particular infections7.

In the literature, there are several examples of Ag nanostructures10,11,12,13. However, many of these methodologies involve multiple reaction and purification steps, which can significantly reduce the overall yield. Furthermore, almost all chemical strategies used to prepare AgNPs require capping agents to stabilize the nanoparticles10,11,12,13,14. One of the most widely used methods is the synthesis of AgNPs by reducing Ag + ions with NaBH4, starting from Ag salts like AgNO3, along with capping agents. However, syntheses using natural products are also well-documented15. Here, we employed a methodology that enables the preparation of AgNPs in a single step, starting from an Acac-based precursor16,17 achieving a 100% reaction yield, as no unwanted by-products are produced, and thus no purification procedures are required.

Several targeted therapies are currently under development to combat drug-resistant bacteria3,18. One notable example is the use of genetically modified bacteriophages that selectively recognize a molecular target in bacteria19. To this end, phage display is a powerful technique to engineer bacteriophages, allowing them to express a foreign peptide on their capsids that is specific to the desired target20. There are several types of phages used in phage display systems, with M13 being the most commonly utilized21. The M13 phage is a filamentous phage, approximately 1 μm in length, and is covered by five coat proteins (pIII, pVI, pVII, pVIII, pIX). It contains a 6407-nucleotide-long circular single-stranded DNA22. As a temperate phage, M13 replicates within its host bacteria without causing cell lysis, making it an economical and accessible source of biomedical materials. Phage technology has been used to identify new peptides, such as ligands for receptors, antigens for tumor diagnosis, and peptides for targeted therapy23,24. Two main methods allow for genetic modification of phages: the phage vector and the phagemid vector22. Additionally, it is possible to display two different peptides, generating dual-display phage particles, which can facilitate target engagement and detection25,26.

Thanks to their high versatility, robustness, and resistance, engineered phages have been exploited in several biomedical applications and are often used as probes in innovative detection systems27. For example, Tian and colleagues developed a bioactive gel system based on the M13 phage through chemical cross-linking. The phage nanofilaments self-assembled into the gel matrix, acting as a high-capacity vehicle for proteins and highly virulent phages that targeted multidrug-resistant E. coli O157:H7 in food products28. Moreover, M13-engineered phages can be functionalized with various nanosystems, such as gold, silver, and silica, for the development of new diagnostic and therapeutic methods29,30,31. Mixing M13 phage with negatively charged antigens, such as nanoparticles or synthetic lipid bilayers, can successfully facilitate the adsorption of targeted drugs and gene delivery systems through electrostatic interactions. Recently, Jin and colleagues designed a hybrid nanoparticle composed of PLT membrane fragments and engineered M13 phage displaying the peptide BCP1. This hybrid exhibited long-circulating properties and bactericidal activity (by expressing the restriction enzyme BglII). They suggested that this novel strategy enhances phage therapy with nanoparticles by engineering biomimetic phages32. Similarly, Olesk and colleagues developed phage-mimicking nanoparticles that structurally resemble the protein-turret distribution found on bacteriophage heads. These nanoparticles are based on core-shell structures, with a silica core and silver-coated gold nanospheres, conjugated with the synthetic antimicrobial peptide Syn-71. The researchers demonstrated that PhaNP@Syn71 nanoparticles are highly effective against the bacterial pathogen Streptococcus pyogenes, showing a dose-dependent inhibition of bacterial growth (> 99.99%) in vitro33.

Here, we generated a new biohybrid structure based on the combination of engineered phages (herein referred to as Li5 phage) and AgNPs to create new molecular complexes that selectively target and kill pathogens. In a series of proof-of-concept experiments, we used these molecular complexes to selectively deliver AgNPs to different E. coli strains. Notably, this system is highly flexible and can be customized to target any pathogens by simply modifying the peptide expressed on the phage capsid before combining it with AgNPs.

Results

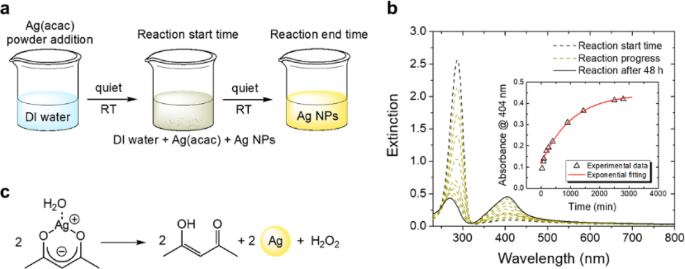

To generate AgNPs, we followed a standard synthesis scheme that led to the formation of a typical yellow silver nano-colloidal suspension (Fig. 1a). To monitor the reaction kinetics over time, we used UV–vis spectroscopy (Fig. 1b). The graph shows the extinction spectra of the same suspension recorded at different time points. The dashed black line refers to the suspension’s extinction profile obtained at the beginning of the reaction (i.e., when the Ag(acac) was added). We observed a more intense peak at 287 nm, which represents the contribution of the absorption by the acetylacetonate ligand. The yellow-dotted spectra were recorded at regular intervals until the end of the reaction. As the reaction progressed, we observed a decrease in the peak at 287 nm, corresponding to the ligand-centered transition of the ketone form of acac, along with a slight blue shift to 282 nm, likely due to the simultaneous presence of the enol form of the free ligand34. Additionally, the peak at 404 nm increased in intensity, accompanied by the formation of an isosbestic point at 324 nm. The decrease at 287 nm suggests the decomposition of Ag(acac) complexes, while the increase at 404 nm indicates the formation of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs)17,35. Notably, the absorbance at 404 nm increased over time (inset in Fig. 1b). We observed no significant variations in the spectra after 48 h (solid black line in Fig. 1b). The inset in Fig. 1b shows the kinetic profile of the reaction obtained by plotting the absorbance of the plasmonic peak at 404 nm as a function of time. The experimental points (triangles) were well fitted using a first-order kinetic model (red solid line) and the following Eq. (1):

$$A={A_infty }+left( {{A_0} – {A_infty }} right){e^{ – kt}}$$

(1)

.

where A∞ is the absorbance measured at the end of the reaction, with a value of 0.45; A₀ is the absorbance measured at the beginning of the reaction; k is the kinetic constant; and t is the time expressed in minutes. The reaction follows a first-order kinetic law, with an observed kinetic constant k ≈ 4 × 10⁻³ min⁻¹.

The absorbance profile described above may be attributed to a spontaneous thermal reaction in which the acetylacetonate ligand releases Ag⁺ ions to produce acetylacetic acid (Hacac). The reduction of Ag⁺ ions produced AgNPs (Fig. 1c), characterized by their typical size-dependent plasmon absorption band centered at 404 nm36.

AgNP synthesis. (a) Schematic representation of the synthesis process of AgNPs using Ag(acac). (b) Extinction spectra of the solution acquired at regular intervals, illustrating the progression of the reaction. The inset shows the kinetic profile of AgNP growth. (c) Proposed mechanism for AgNP synthesis.

The AgNPs were negatively charged, as shown by Z-potential measurements, with a surface charge value of -48.7 mV (Table 1). This negative charge confers stability to the colloidal solution by minimizing self-aggregation. Given the small changes in Z-potential, we can assume that both buffers have similar effects on aggregation.

To investigate the obtained AgNPs, we performed transmission electron microscopy in scanning mode (S/TEM), which enabled both structural characterization and point-specific chemical analysis. We observed clearly distinguishable AgNPs using bright-field microscopy (Fig. 2a–b) and high-angle annular dark-field imaging (HAADF; Fig. 2c–d). The crystalline structure of the AgNPs was also evident (Fig. 2b, d). Furthermore, we measured the distance between the interatomic planes of the crystalline lattice to be 2.5 Å, which is consistent with previously published work (Fig. S1)37.

To assess the mean diameter of the AgNPs, we measured the diameter of every AgNP present in each acquired image. We observed that the AgNPs in aqueous solution exhibited very small dimensions, with a mean diameter centered at approximately 9 nm (Fig. 2e). To further characterize the AgNPs, we analyzed them using energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX). We found that the primary signal was attributed to the presence of Ag, as indicated by the peaks emitted between 2.9 and 3.5 keV (Fig. 2f). Signals at lower keV levels indicated the presence of both carbon and oxygen (Fig. 2f). These observations confirm that the synthetic protocol successfully produced very small AgNPs.

Structural characterization of AgNPs by transmission electron microscopy. (a,b) High-resolution bright-field images acquired through S/TEM; (c,d) High-angle annular dark-field images acquired through S/TEM; (e) Graph illustrating the distribution of AgNPs. In the inset, the S/TEM bright-field image displays the smallest observed AgNPs. (f) EDX spectrum of AgNPs.

Based on the information obtained from the nanoparticle size distribution diagram, we calculated the molar concentration of AgNPs in the ultrapure water suspension. AgNPs with a diameter of approximately 10 nm have an extinction coefficient (ε) of 5.56 × 108 L mol−1 cm−138. According to the Lambert-Beer law, an AgNP suspension with an absorbance (A) of 0.45 and an optical path length of 1 cm has a concentration of 800 pM, as determined by the following Eq. (2)

$$c=frac{A}{{ell varepsilon }}=frac{{0.45}}{{5.56 times {{10}^8};{text{L}};{text{mo}}{{text{l}}^{ – 1}}}}=8 times {10^{ – 10}};{text{M}}$$

(2)

.

We next sought to combine the newly synthesized AgNPs with the Li5-engineered phage expressing the RKILRAGPLX peptide on its capsid, fused to the pVIII protein. This phage was selected against E. coli LE392 (F − strain) to detect both E. coli F − and F + strains27. Using bioinformatics tools, we estimated the isoelectric point (pI) of Li5 to be 6.3. Based on this result, the phage surface is considered positively charged at pH values below the pI and negatively charged at pH values above the pI (Fig. 3).

Schematic representation of Li5 phage. (Top) Capsid structure of Li5 phage. The N-terminal of the pVIII protein is highlighted in blue and green. The blue amino acids represent the wild-type protein, while the green amino acids represent the foreign peptide. (Middle) Primary amino acid sequence of the Li5 N-terminal pVIII protein. (Bottom) Predicted charges exposed on the capsid surface when subjected to different pH values.

We next incubated AgNPs with and without Li5 using different ion-type buffers (Tris-buffered saline (TBS) and phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)) at pH 5 and 6. Incubation of Li5 with AgNPs resulted in the formation of solutions with varying intensities of yellow color. In contrast, in the samples with PBS and TBS without phage, the solution appeared white with brown silver precipitates at the bottom. To better characterize the AgNPs@Li5 complexes, we used UV–vis absorption spectroscopy (Fig. 4a-b). The UV-vis spectra obtained in ultrapure H₂O showed a peak at 405 nm due to AgNPs, which was absent when the AgNPs were dispersed in the PBS or TBS buffer alone. However, the spectra of AgNPs@Li5 solutions exhibited a defined band centered at 420 nm, which indicates the presence of AgNPs in the solution (Fig. 4a-b). Additionally, there was a visible shift in the AgNPs plasmon absorption, which could be attributed to slight aggregation of the nanoparticles due to the presence of the saline buffer and Li5 phages in the solution. A decrease in the absorption band of AgNPs was also observed as a function of both pH and the saline buffer used. To this end, TBS seems to influence the quenching of the plasmonic band more than PBS.

UV-vis spectra of the AgNPs@Li5 complexes. (a,b) UV-Vis spectra of the AgNPs@Li5 resuspended in PBS and TBS, respectively, at two different pH values. The peak positions of the plasmonic absorption bands are highlighted with colored circles.

We next calculated the zeta potential (z-potential) values, which were − 36 mV and − 33.1 mV for AgNPs@Li5 complexes obtained in PBS at pH 6 and pH 5, respectively, and − 30.9 mV and − 35.3 mV in TBS at pH 6 and pH 5, respectively, suggesting that the AgNPs@Li5 assemblies are fairly stable in PBS (Table 1). In contrast, z-potential values of -29 mV and − 27.6 mV were obtained for AgNPs dissolved in PBS and TBS, respectively.

We calculated the ionic strength of the AgNPs@Li5 complexes in PBS and TBS at pH 5 and pH 6 using Eq. (3):

$$I=frac{1}{2}sumlimits_{{i=1}}^{n} {{c_i}z_{i}^{2}}$$

(3)

.

Where i is the i-th species, and n, ci, and zi are the number, concentration, and charge of the ion species in solution. We found that the ionic strength was higher for the AgNPs@Li5 complexes in TBS compared to those in PBS, independent of pH (Table 2).

We also observed that AgNPs@Li5 solutions in PBS showed a higher absorbance at the AgNPs peak compared to those in TBS (Fig. 4), indicating that PBS contributed to the formation of complexes more efficiently than TBS. For this reason, we analyzed only the AgNPs@Li5 complexes in PBS from this point onward.

Surface charge study. CA analysis of GOPS (red line), AgNPs (blue line), Li5 (black line), and AgNPs@Li5 (magenta line) at different pH values (silicon substrate). The maximum CA values for Li5 and AgNPs@Li5 are highlighted by grey and magenta rectangles, respectively.

To further investigate the surface charges of the AgNPs@Li5 systems in PBS, we conducted a contact angle (CA) study as a function of pH (Fig. 5). We observed a significant change in the surface charge profile, which depended on the type of functionalization applied to the silicon substrate. Specifically, the GOPS-modified surface (black line in Fig. 5) exhibited high CA values, with an average of 71.7°, and showed low responsiveness to pH due to the non-polar nature of the silane. The wettability increased on the surface modified with GOPS + Li5 phage (black line), with an average CA value of 38.4°, due to the ionization of exposed phage peptides and the consequent increase in surface hydrophilicity. On this surface, the CA reached a maximum of ~ 55° at pH 6 and 10 (grey rectangles in Fig. 5) and decreased at other pH values. The maximum CA of 55° at pH 6 is consistent with the estimated pI of Li5 obtained from bioinformatics tools (Fig. 3). This behavior changed in the presence of AgNPs. Indeed, the surface modified with only AgNPs (blue line) exhibited high CAs with an average of 59.5°, which decreased to ~ 30° in the case of the AgNPs@Li5 surface (magenta line in Fig. 5). Moreover, the pH of maximum CA measured on the Li5 surface changed in the AgNPs@Li5, showing the highest values at pH 5 and 11 (magenta rectangles in Fig. 5). These data suggest a modification of the phage’s charge profile and pI due to its complexation and strong electrostatic interactions with the AgNPs. The observed behavior of AgNP@Li5 may be attributed to conformational changes in the Li5 structure and alterations in their surface charge arrangement, which occur as a consequence of the capsid peptides’ interaction with the AgNPs.

We next examined the structure of the AgNP@phage complexes using TEM. The images revealed AgNPs decorating the entire phage surface (Fig. 6). Figure 6a is a conventional TEM image acquired in brightfield mode (C/TEM BF), showing distinct bundles of phages immersed in the PBS matrix. Images in Fig. 6b-d were acquired at the same sample point using three different techniques to confirm the presence of phages decorated with AgNPs. Specifically, Fig. 6b presents a C/TEM BF image acquired using a direct electron imaging camera with a controlled low electron dose. This system enables rapid image acquisition, allowing the visualization of a bundle of phages approximately 1 μm in length. Additionally, distinct AgNPs are clearly visible and distributed along the entire phage surface. The energy-filtered TEM image on the carbon plasmon (EF/TEM@C plasmon) allows visualization of the carbon-based components deposited onto the continuous carbon lacey film of the sample holder grid (Fig. 6c). The contrast of the filamentous shapes confirms the presence of carbon-based structures, while the AgNPs, as expected, are poorly visible. Figure 6d shows the S/TEM HAADF image, in which the phage’s filamentous shapes and the AgNPs are visible with excellent contrast.

The EDX spectrum is shown in Fig. 6e. The signals related to all elements present in the liquid matrix are distinguishable in the spectrum. The attribution of the main signals with their relative energy in keV is shown in Fig. 6e. The presence of distinct peaks for Na (1.04 keV), P (2.1 keV), Cl (2.63 keV and 2.83 keV), and K (3.32 keV) can be attributed to the saline matrix of PBS. The peak at 0.38 keV is attributable to the Kα₁ and Kα₂ nitrogen signals (insets in Fig. 6e). The nitrogen signal clearly indicates the presence of phages, as they are the only nitrogen-containing components in the fluid matrix. The peaks centered at 2.99 and 2.15 keV are related to the Lα₁, Lα₂, and Lβ₁ signals of silver (insets in Fig. 6e). The complete information acquired by microscopic techniques strongly confirms the correct presence of the AgNPs-phage complex.

To estimate the number of phages present in the complex samples, we performed an indirect quantification by calculating the difference between the phages initially added during functionalization and the amount found in the post-functionalization supernatant (Figure S2). We found that AgNPs@Li5 pH6 in PBS collected the highest number of phages compared to the other conditions, suggesting that both the type of buffer and pH play a role in the self-assembly of phage-AgNPs.

Transmission electron microscopy analysis of AgNPs@Li5 complexes. (a) C/TEM BF; (b) C/TEM BF with controlled electron dose; (c) EFTEM@C plasmon; (d) S/TEM HAADF. AgNPs appear round and dark (indicated by yellow arrows), while the Li5 phage appears as translucent filaments (indicated by red arrows). (e) EDX spectrum acquired from the region corresponding to images in (b) and (d). The insets show magnifications of the nitrogen and silver signals. The main signals present in the spectrum are displayed in the panel below the graph.

The activity of the complexes was evaluated using the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimal bactericidal concentration (MBC) tests. The MIC determines the lowest concentration of the tested complexes that inhibits bacterial growth, while the MBC identifies the lowest concentration that kills the bacteria. To test the antibacterial activity of AgNPs@Li5/PBS at pH 5 and 6, we incubated them with three different E. coli strains (TG1, F-, O157:H7), all of which are selectively recognized by the Li5 phage27. We found that AgNPs/PBS at pH 5 and 6 showed no antibacterial activity (Figure S3a). These data suggest that the AgNPs, in the presence of PBS, aggregate and thus do not interact effectively with the bacteria. This is consistent with the UV-vis data, which show that the spectra of AgNPs/PBS lose the peak at 405 nm, associated with AgNPs (Fig. 4a). Similarly, we observed that Li5 alone also presented no antibacterial activity (Figure S3b). In contrast, for E. coli TG1, we observed that the MICs for both AgNPs@Li5/PBS at pH 5 and 6, as well as AgNPs/H2O, were obtained at a dilution factor of 1:8 [corresponding to ~ 1 × 10¹⁰ AgNPs@Li5 complexes for both conditions in PBS at pH 5 and 6 (Fig. 7a)]. However, the efficacy of the antibacterial activity was significantly different among the three testing conditions at a dilution of 1:16 (corresponding to ~ 6 × 10⁹ AgNPs@Li5 complexes for both conditions in PBS at pH 5 and 6). Specifically, the data indicate that the AgNPs@Li5/PBS pH 6 complexes exhibited the best antibacterial activity (Fig. 7a). For E. coli F-, we found that the MICs were obtained at a dilution of 1:8 for both AgNPs/H2O and AgNPs@Li5/PBS pH 5 complexes, and at 1:16 for AgNPs@Li5/PBS pH 6 (Fig. 7b). When we compared antibacterial activity at a 1:16 dilution, we found that AgNPs@Li5/PBS pH 6 prevented bacterial growth by ~ 95%, which was statistically significant compared to the other two conditions. Additionally, our results suggest that AgNPs@Li5/PBS pH 5 complexes exhibited better antibacterial activity compared to AgNPs/H2O (Fig. 7b). Moreover, for E. coli O157:H7, we observed that the MICs for AgNPs@Li5/PBS complexes (pH 5 and pH 6) were obtained at a dilution factor of 1:8. However, at this dilution, AgNPs/H2O showed basal bacterial growth (Fig. 7c), indicating that AgNPs/H2O had no antibacterial activity at a 1:8 dilution. In contrast, at a dilution of 1:16, we found similar antibacterial activity for all three testing conditions (Fig. 7c). These data indicate that the O157:H7 strain is more resistant to AgNPs, which is in line with the literature suggesting that O157:H7 is more resilient to various forms of stress39. To test the target specificity of our AgNPs@Li5 complex, we incubated it with P. aeruginosa, a bacterial strain not recognized by the Li5 phage27. We found that with this bacterial strain, AgNPs/H2O showed a MIC value at 1:2, while all the AgNPs@Li5 complexes allowed cell growth (Fig. 7d). Taken together, the data suggest that Li5 exhibited antibacterial activity with similar MIC values for E. coli TG1 and E. coli F-, demonstrating inhibition of bacterial growth at a 1:16 dilution. In contrast, the antibacterial activity against the E. coli O157:H7 strain was lower (with a dilution value of 1:8) compared to other E. coli strains. These results highlight the specificity of the AgNPs@Li5 complex, which increases the antibacterial activity of AgNPs only with strains recognized by the Li5 phage.

Antibacterial activity of AgNPs@Li5. The graphs show the percentage of bacterial growth of three E. coli strains (a–c) recognized by the Li5 phage and P. aeruginosa (d) after 18 h of incubation with scalar dilutions of AgNPs and AgNPs@Li5 at the indicated pH levels. Data were analyzed by a two-way ANOVA test with Tukey’s multiple comparisons. Confidence interval 95%. (***) indicates a p-value < 0.0001; (**) indicates a p-value = 0.0001; (*) indicates a p-value of 0.03; For each experiment, n = 3. (see also Figure S4).

To assess whether AgNPs@Li5 exhibited bactericidal activity, we used the MIC endpoint solutions and cultured them under optimal conditions (see Materials and Methods). For E. coli TG1, we found that the minimal bactericidal concentration (MBC) was at a 1:4 dilution for the bacteria previously incubated with AgNPs/H2O. In contrast, the MBC was at a 1:8 dilution for bacteria previously incubated with the AgNPs@Li5 complexes (Table 3 and Figure S5). For E. coli F-, we found that the MBC was at a dilution of 1:16 for the bacteria previously incubated with AgNPs@Li5 PBS pH 6, while for those incubated with AgNPs@Li5 PBS pH 5 and AgNPs/H2O, the MBC was at a dilution of 1:8. For E. coli O157:H7, we found that the MBC was at a dilution of 1:8 for the bacteria previously incubated with AgNPs@Li5 PBS pH 5 and 6, while it was at a dilution of 1:4 for the bacteria that had been incubated with AgNPs/H2O. In contrast, for P. aeruginosa, we observed an MBC value of 1:2 for the bacteria previously incubated with AgNPs/H2O. The AgNPs@Li5 complexes did not kill the bacteria (Table 3 and Figure S5), which is consistent with the fact that Li5 does not recognize P. aeruginosa. Overall, our data show that AgNPs@Li5 exhibit highly selective antibacterial activity conferred to them by the Li5 phage.

Moreover, we performed a dose-response analysis to assess the potency of the complexes in terms of the Effective Concentration 50 (EC50; see Table 4 and Figure S6). The data suggest that both AgNPs@Li5 PBS pH 6 and AgNPs@Li5 PBS pH 5 are highly effective, exhibiting similar potency, with only minor differences in EC50 values for the treatment of E. coli strains. In contrast, AgNPs/H2O demonstrates lower potency against E. coli strains, requiring higher concentrations to achieve the same effect (higher EC50 values). For P. aeruginosa, AgNPs/H2O appears to be the most potent treatment, showing efficacy at much lower concentrations compared to the other two complexes.

We also evaluated the HillSlope values (Table 5), which indicate the sensitivity of the response to changes in concentration. Higher HillSlope values suggest that the response changes more rapidly with small variations in concentration, while lower HillSlope values indicate that the response changes more gradually. We found that AgNPs@Li5 PBS pH 5 exhibited the highest sensitivity for E. coli F- and E. coli O157:H7, but showed a lower HillSlope for P. aeruginosa. In comparison, AgNPs@Li5 PBS pH 6 demonstrated moderate sensitivity for most bacterial strains. On the other hand, AgNPs/H2O generally showed lower sensitivity to dose changes across all strains.

Discussions

Antibiotic resistance is a growing problem arising from the evolutionary adaptation of bacteria to antimicrobial agents, rendering them less susceptible or entirely resistant to treatment1. It undermines the efficacy of conventional antibiotics, leading to prolonged infections, increased healthcare costs, and elevated mortality rates. In response to this challenge, targeted therapy has emerged as a promising approach3,18,19,20,40. It involves the precise identification and targeting of specific molecular pathways within bacterial pathogens, thereby bypassing the mechanisms of antibiotic resistance. Converging evidence shows the potential of AgNPs to target antibiotic-resistant bacteria4,9. This approach leverages the broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity of AgNPs, which can effectively target a wide range of bacterial strains, including those resistant to conventional antibiotics. Additionally, AgNPs possess a unique mode of action that involves disrupting multiple cellular processes, such as cell membrane integrity, DNA replication, and protein synthesis, thereby minimizing the likelihood of resistance development4,9. However, there are also significant drawbacks associated with their use in targeted therapy, which have limited their development. Most notably, there are concerns regarding the potential cytotoxicity and adverse effects of AgNPs on human cells upon prolonged or high-dose exposure9. Furthermore, there is a risk of AgNPs interacting with other components in biological systems, potentially leading to unforeseen interactions or unintended consequences9. To circumvent these issues, we developed AgNPs@Li5 complexes and showed that they can selectively kill bacteria. The selectivity arises from the presence of the Li5 phage. As we previously described, the Li5 phage expresses a foreign peptide (RKILRAGPL) in-frame with the N-terminal coat protein pVIII of the filamentous phage M1327. The presence of this foreign peptide confers to the phage the ability to selectively interact with several E. coli strains, both F’ and F-, but not with other Gram-positive or Gram-negative bacteria27. To this end, the data presented here clearly show that the AgNPs@Li5 exhibit bactericidal activity only against bacterial strains recognized by the Li5 phage, while having no effects on P. aeruginosa, a bacterial strain not recognized by Li5.

These results also highlight that the AgNPs retain their antibacterial properties when complexed with Li5, suggesting that other M13 phages would similarly not interfere with the AgNPs’ activity. Indeed, the system described here is highly flexible; by simply replacing Li5 with another phage that exposes a different foreign peptide on its capsid, one can change the target to which the AgNPs are delivered without losing the antibacterial properties of the AgNPs. For example, AgNPs have been investigated for their potential applications in cancer treatment, as they can induce apoptosis or necrosis in cancer cells through various mechanisms, including the generation of reactive oxygen species, disruption of mitochondrial function, and activation of cell death pathways41,42. By combining these phages with AgNPs using the approach we developed here, nanoparticles can be directed specifically to cancerous cells without affecting healthy ones, as the phages will not recognize them. For instance, we have previously identified phages that recognize selective subpopulations of multiple myeloma cells isolated from patients’ bone marrow43. Additionally, there would be no need to use high concentrations of AgNPs. This is notable because the toxicity of AgNPs often stems from the high concentrations required for them to achieve the desired effect9. However, by directly delivering AgNPs to a specific target, the Li5 phage (or another phage specific to a different target) reduces their dispersion in the solution, thereby reducing the amount of AgNPs needed to kill bacteria, as shown by our MBC data. Indeed, we report that the concentration required to kill E. coli TG1 is 50% lower for AgNPs@Li5 compared to AgNPs alone.

We studied the AgNPs by TEM and found that they consist of nearly spherical nanoparticles of ~ 10 nm in diameter with a Z-potential value of -48.7 mV, indicating high stability of the colloidal solution and excluding the possibility of self-aggregation processes. The size of AgNPs reported here is smaller than what was observed in our previous study (AgNPs of 20 nm), where the synthesis was carried out in the presence of acetone as an initiator7. This difference can be attributed to a higher activation of the reaction by the initiator, which results in larger AgNPs. The negative z-potential of the AgNPs and the positive charges of the Li5 phage at pH below the pI suggest the presence of strong electrostatic interactions in the AgNPs@Li5 complexes. This is supported by the CA study performed on modified silicon substrates at different pH levels. Transitioning from the Li5 to the AgNPs@Li5 surface, the analysis revealed an increase in surface wettability caused by the stronger electrostatic interactions occurring in the Ag-phage complex, as well as a shift in the pI due to the modification of phage surface charges by AgNP coverage.

After dispersing AgNPs in TBS or PBS, we observed a decrease in the peak at 415 nm in the UV-Vis spectra. This decrease is attributable to the electrostatic repulsion between AgNPs and buffer ions, such as sodium (Na+), potassium (K+), chloride (Cl−), and phosphate (PO43−), which results in nanoparticle aggregation and precipitation. These observations are consistent with previous literature reports44,45,46,47,48. Additionally, a red shift of the AgNPs’ plasmon absorption was clearly visible when the nanoparticles were not in free water. This shift is likely due to slight aggregation of AgNPs caused by the presence of buffer saline or Li5 phages, depending on the ionic strength of the buffer (see Table 2). When Li5 phages were present in the buffers, AgNPs did not precipitate, as evidenced by the peak at 415 nm in the UV-Vis spectra. This finding indicates that the phages were stabilizing the AgNPs in physiological solutions. Moreover, the peak is slightly shifted compared to the AgNPs peak obtained in H2O, indirectly indicating an interaction between the AgNPs and the Li5 phage. This interaction may be attributed to the polyelectrolytic nature of the phages, which interact with ions, stabilizing the capsid-protein interfaces with the solvent, forming salt bridges, and facilitating the AgNP-phage interaction49. However, the differing behaviors observed among the obtained complexes appear to be primarily influenced by the type of ions present in the buffer and the pH values. Li5 in PBS buffer showed higher optical absorption values compared to the Li5 complexes in TBS, suggesting that in PBS buffer, Li5 helps maintain a greater concentration of AgNPs in solution.

Putra and colleagues reported that M13 in aqueous 10 mM NaCl exhibits a negative Z-potential and assumes a spherical size. Conversely, with 10 mM HCl, the Z-potential changes to positive and the diameter appears increased (consistent with aggregation)50. Applying these observations to our findings, the presence of HCl exclusively in the TBS buffer leads to phage aggregation, reducing its availability to collect AgNPs. On the other hand, all the obtained AgNPs-Li5 complexes had similar negative Z-potential values, indicating that, after formation, the complexes remained stable under all conditions. The resulting complexes appeared as nanostructures of AgNPs-Li5 distributed across the entire bacteriophage structure, forming phage bundles of micrometer length. Additionally, the EDX probe allowed us to identify the presence of Ag, along with nitrogen and atomic species typical of salts, suggesting that the AgNPs and phage are closely associated with the salts in the same regions.

The complexes, consisting of AgNPs electrostatically assembled with the entire phage structure, are shown in the TEM image (Fig. 4a). We observed that the two elements formed a network, with AgNPs distributed along the entire length of the phage capsid. Additionally, EDX analysis confirmed the sample composition, revealing the network formation through the presence of nitrogen (N)—an atomic species typically associated with the proteins on the phage surface—and Ag elements (Fig. 4b). Oxygen (O), sodium (Na), chloride (Cl), potassium (K), and phosphate (P) were also present due to the buffer.

Consistent with the findings of Tian and colleagues, who described the self-assembly of phages in a gel system28we observed phage-phage and phage-particle self-assembly driven by electrostatic interactions and the presence of salts in the samples, as confirmed by the UV-vis, STEM, and EDX data.

In the dose-response analysis, we observed that AgNPs@Li5 PBS pH 6 and AgNPs@Li5 PBS pH 5 treatments were highly effective and potent for E. coli strains, exhibiting lower EC50 values compared to AgNPs/H2O. Furthermore, AgNPs@Li5 PBS pH 6 demonstrated the most stable response with moderate HillSlope values and consistent sensitivity across different E. coli strains, making it a reliable formulation for applications requiring consistent performance. In contrast, for P. aeruginosa, only AgNPs/H2O showed a very low EC50 value, suggesting that the AgNPs@Li5 complexes reduce the random distribution of the AgNPs, making them less available to induce toxicity.

To generate a hybrid structure, Olesk and colleagues coated nanoparticles with phage-derived peptides to develop phage-mimicking nanoparticles. In contrast, we utilized the phage as a scaffold to anchor the AgNPs, simplifying the process33. Moreover, Scibilia and colleagues functionalized AgNPs with engineered phage-displayed peptides targeted to P. aeruginosa. However, in their study, the AgNPs were synthesized through laser ablation, and the biohybrid material was only verified using Raman spectroscopy44. In contrast, our approach involved synthesizing AgNPs via a chemical method, and we verified the resulting aggregated system using multiple optical techniques. We also evaluated the antibacterial activity and specificity of the AgNPs@Li5 complexes against bacterial targets.

Overall, our study enhances the understanding of electrostatic functionalization of engineered phages and nanoparticles, with a focus on the isoelectric point. The antibacterial results highlight how the complexes improve dose-response efficiency compared to AgNPs alone. Most importantly, these complexes exhibit highly selective antibacterial activity against specific E. coli strains, minimizing the impact on other bacteria.

Conclusions

In this study, we developed a novel biohybrid complex by combining Li5-engineered phages, selective for specific E. coli strains, with AgNPs for a targeted therapy approach. The data demonstrate how the AgNPs@Li5 complex effectively targets different E. coli strains, exhibiting potent antibacterial activity. Moreover, the system addresses some of the challenges associated with using AgNPs in targeted therapy. By directing the AgNPs to specific toxic species, this approach reduces the overall amount of AgNPs needed, offering two immediate benefits: minimizing the quantity of AgNPs required and selectively targeting them to specific cells. This reduces their toxicity and minimizes the unwanted side effects that arise from interactions with healthy cells.

Additionally, it is important to highlight the flexibility of this system, which can be easily customized to target any pathogen by simply altering the peptide expressed on the phage capsid before combining it with AgNPs. These findings open the door to new strategies in targeted therapy, leveraging multifunctional bio-nano systems that combine the selectivity of peptide-based probes with the therapeutic power of nanoparticles.

Methods

AgNPs synthesis

AgNPs were synthesized using the method described previously36. We employed a chemical synthesis in solution, utilizing the complex 2,4-pentanedionate Ag(I), formerly known as silver acetylacetonate [Ag(acac)], as the sole reagent and precursor of metallic silver. For this purpose, we prepared a 0.2 mM aqueous solution of Ag(acac) at room temperature, without the use of additional reducing agents or stabilizing ligands.

UV-Vis measurements

The UV/vis absorption spectra of the AgNPs suspensions (0.2 mM) were recorded in 1 cm quartz cuvettes at room temperature using a Jasco V-570 spectrophotometer with 2 nm slits. The UV/vis absorption spectra of the AgNPs-Li5 complexes were acquired using a Nanodrop 1000 Spectrophotometer from Thermo Scientific with a 1 mm optical path.

Structural and chemical characterization

For materials characterization, we used a Jeol JEM ARM200F with a cold-FEG filament and probe Cs-corrected operated at 200 kV. We used conventional TEM (C/TEM), energy-filtered TEM (EF/TEM), and scanning (S/TEM) high-angle annular dark field (HAADF) acquisition mode. To acquire the images, we used a GATAN RIO2 CMOS camera for BF C/TEM, GATAN K2 single-electron camera for controlled dose BF images (1500 e-/Ų) and EF/TEM, and a JEOL dark field detector for S/TEM HAADF imaging. For the chemical analysis, we used a 100 mm² energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) spectrometer. To perform the analyses, we deposited a drop of the AgNPs suspension onto a gold grid with a thin lacey carbon film and vacuum-dried it for 24 h.

Contact angle analysis

Silicon substrates for the CA study were prepared as follows: A 3 × 3 mm section of silicon was functionalized through a series of steps. First, it underwent a cleaning process by immersing it in 20 µL of a piranha solution [H₂O₂:NH₃:H₂O (1:1:4)] at 80 °C for 25 min, followed by treatment with an acid solution (HCl: H₂O₂, 1:7.5) at room temperature for 10 min. Lastly, it was rinsed with deionized water. For the AgNPs and AgNPs@Li5 surfaces, the substrate was then spotted with a solution of AgNPs or AgNPs@Li5, respectively, and allowed to dry at 25 °C for 20 min. In contrast, for GOPS and Li5 surfaces, the substrate underwent silanization by chemical vapor deposition (CVD) using GOPS silane at 125 °C for 4 h. Lastly, for the Li5 surface, the substrate was immersed in a solution containing 10¹¹ copies of Li5 phage, incubated overnight at 4 °C, and rinsed with a washing buffer composed of 50 mL PBS + 25 µL 0.05% Tween 20. To evaluate the pI and the surface charge profile of modified silicon surfaces, the CA was measured by drop casting using a 1 µL drop of acetate buffer at pH 3 and 4, phosphate buffer at pH 5–6 and 8, deionized water at pH 7, carbonate buffer at pH 9 and 10, and ammonium buffer at pH 11 and 12.

Bacterial strains

E. coli TG1 was used for bacteriophage amplification and, together with E. coli F- and E. coli O157:H7, for antimicrobial tests. Cells were cultured in Luria-Bertani broth (LB, Sigma-Aldrich) and maintained on MacConkey Agar plates and 20% glycerol stocks at -80 °C. Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ATCC 27853) was used for the cross-reactivity antimicrobial test and cultured in LB, maintained on 20 g/L Cetrimide agar plates, and stored in 20% glycerol stocks at -80°C51.

Phage clone

The Li5-engineered phage clone was previously isolated in our laboratory using affinity-selection procedures27. It displays the foreign peptide RKILRAGPL, which interacts with E. coli strains. The isoelectric point (pI) value of the Li5 N-terminal-pVIII was calculated using the ProtParam tool available on the Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics Expert Protein Analysis System (ExPASy) proteomics server (https://web.expasy.org/protparam). The algorithm calculates the protein pI using pK values of amino acids. These values were determined by examining polypeptide migration between pH 4.5 and 7.3 in an immobilized pH gradient gel environment with 9.2 M and 9.8 M urea at 15–25 °C, respectively52.

Phages production

The E. coli strain TG1 (F’, Kan-, Amp-, lacZ-) culture (OD600 = 0.7) was infected with Li5 (Amp+), then incubated at 37 °C in static conditions for 15 min, followed by shaking at 250 rpm for 20 min. After incubation, suitable aliquots of the culture were plated onto LB agar plates containing 50 µg/mL ampicillin and incubated at 37 °C in static conditions. One infected colony was inoculated into a 10 mL LB medium containing 50 µg/mL ampicillin and incubated at 37 °C with shaking at 250 rpm until reaching OD600 = 0.2. Subsequently, isopropylthio-β-galactoside (IPTG, 40 µg/mL) and the helper phage M13K07 (Kan+) (10⁹ TU/mL) were added to the medium and incubated at 37 °C in static conditions for 30 min, followed by further incubation with gentle shaking for 30 min. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 8000 × g, transferred to 500 mL LB medium containing 50 µg/mL ampicillin and 50 µg/mL kanamycin, and incubated overnight with shaking at 250 rpm at 37 °C. The infected culture was centrifuged at 8000 × g for 20 min at 25 °C. The supernatant was then mixed with 25% (v/v) premade PEG/NaCl solution, cooled on ice for 4 h, and precipitated by centrifugation at 15,000 × g for 45 min at 4 °C. The pellet was resuspended in 10% (v/v) TBS, mixed again with 25% (v/v) premade PEG/NaCl, cooled on ice for 4 h, and centrifuged as above. The resulting pellet, containing phage particles, was suspended in 10% (v/v) TBS or PBS buffer, filtered through a 0.22 μm-pore size membrane, and stored at 4 °C. The Li5 phage concentration was assessed by transducing units per milliliter (TU/mL), according to Eq. (4):

$${text{TU/mL=}}frac{{{text{EquationNumber}};{text{of}};{text{colonies}}}}{{left( {{text{Volume}};left( {0.1;{text{mL}}} right) times {text{dilution}};{text{factor}}} right)}}$$

(4)

.

All assays were performed in triplicate.

Phage suspension buffer

To evaluate the influence of phage suspension buffer on the phage assembly with AgNPs, different pH and ion-type buffers were used. 0.01 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) composed of potassium phosphate monobasic (0.2 g/L, Lickson), sodium phosphate dibasic (1.15 g/L, Sigma-Aldrich), sodium chloride (8 g/L, Applichem), and potassium chloride (0.2 g/L, AnalytiCals Carlo Erba) were mixed and solubilized in ultrapure water. Tris-buffered saline (TBS) composed of Tris-hydrochloride (7.88 g/L, Euroclone) and sodium chloride (8.77 g/L, Applichem) was mixed and solubilized in ultrapure water. The pH of both buffers was adjusted with 5 N HCl and 5 N NaOH to give the final pH of 5 and 6. Both buffers are commonly used in phage preparation and applications.

Phage-AgNPs networks Preparation

The phage-AgNPs networks were prepared according to the procedure described in the literature44,53 with some modifications. Briefly, in glass tubes, AgNPs were incubated overnight with the phage clone (titer of 1 × 10¹² phage) in a 4:1 ratio at 37 °C with orbital shaking at 320 rpm (KS130 Basic IKA). The samples were left to decant for 2 h at room temperature to remove any sediment. Then, the supernatant was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 30 min to separate the AgNPs-phage network from the unbound free silver (the supernatant was quantified for phage titer by TU/mL as described above). The pellet was resuspended in the starting buffer and stored in the dark until utilization. The phage titer obtained from the supernatant was used to perform an indirect quantification by calculating the difference from the phage initially added during functionalization.

Z-potential measurements

The z-potentials of free AgNPs and AgNPs functionalized with phages were determined using a Zetasizer Nano-Z (Malvern Instruments). Measurements were taken in ultrapure water at 25 °C at 20 mV using a capillary electrophoresis system. Data were collected using the Smoluchowski model with a 100 µL sample in triplicate.

Antibacterial assay

E. coli strains were cultured in LB broth. The semi-exponential broth cultures were prepared at a final concentration of ~ 10⁵ bacteria/mL, starting from a 0.5 McFarland inoculum (equivalent to 1.5 × 10⁸ bacteria/mL). Then, 150 µL of the bacterial solution with serial two-fold dilutions of AgNPs alone or AgNPs@Li5 complexes was dispensed into a 96-well plate (3 replicates per condition) and incubated at 37 °C for 18 h. Bacteria without AgNPs were used as a positive control. The minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) was determined as the lowest concentration of AgNPs or AgNPs@Li5 complexes that prevented bacterial growth. The plates were read at 540 nm (using a Multiskan Reader, LabSystem), and the following formula was applied to obtain the percentage of bacterial growth (5):

$$% ;{text{bacteria}};{text{growth}}=frac{{{text{media}};{text{value}};{text{sample}}}}{{{text{media}};{text{value}};{text{bacteria}};{text{growth}}}} times 100$$

(5)

.

The dilution factor for MIC determination was chosen to ensure a consistent evaluation of antimicrobial activity. A two-fold (1:2) serial dilution was used, as it provides a balance between sensitivity and practicality. Starting from the MIC endpoints, the minimal bactericidal concentration (MBC) was determined by subculturing onto MacConkey agar plates and was defined as the lowest concentration of the compound able to reduce bacterial viability by over 99.9% compared to the initial inoculum. The same protocol was used to test the specificity of AgNPs@Li5 complexes with cultured P. aeruginosa.

Statistical analysis

All samples were analyzed in triplicate, and the experimenters were blinded to the conditions and groups. Data were analyzed as mean ± standard error (SE) and expressed as percentages versus uncoated scaffolds (Ti). ANOVA test p-values are reported, with *p < 0.05 or **p < 0.01 indicating significant differences between scaffolds as reported by the Holm post hoc test. We conducted a visual inspection of the data to ensure normal distribution prior to performing the ANOVA. The confidence interval is 95%.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AgNPs:

-

Silver nanoparticles

- Ag(acac):

-

Silver acetyl acetonate

- Li5:

-

M13 bacteriophage

- TEM:

-

Transmission Electron Microscopy

- C/TEM:

-

Conventional TEM

- EF TEM:

-

Energy filtered TEM

- S/TEM:

-

Scanning TEM

- HAADF:

-

High-angle annular dark field

- BF:

-

Bright-field

- EDX:

-

Energy-dispersive X-ray

- PBS:

-

Phosphate-buffered saline

- TBS:

-

Tris-buffered saline

- MIC:

-

Minimal inhibition concentration

- MBC:

-

Minimal bactericidal concentration

References

-

Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet 399, 629–655 (2022).

-

Tang, K. W. K., Millar, B. C. & Moore, J. E. Antimicrobial resistance (AMR). Br. J. Biomed. Sci. 80, 11387 (2023).

-

Yang, B., Fang, D., Lv, Q., Wang, Z. & Liu, Y. Targeted therapeutic strategies in the battle against pathogenic bacteria. Front. Pharmacol. 12, 673239 (2021).

-

Xu, Z., Zhang, C., Wang, X. & Liu, D. Release strategies of silver ions from materials for bacterial killing. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 4, 3985–3999 (2021).

-

Ma, Y. et al. A portable sensor for glucose detection in Huangshui based on blossom-shaped bimetallic organic framework loaded with silver nanoparticles combined with machine learning. Food Chem. 429, 136850 (2023).

-

Kumar, A. et al. Biogenic metallic nanoparticles: biomedical, analytical, food preservation, and applications in other consumable products. Front. Nanotechnol. 5 (2023).

-

Calabrese, G. et al. A new Ag-nanostructured hydroxyapatite porous scaffold: antibacterial effect and cytotoxicity study. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 118, 111394 (2021).

-

Kapoor, D. U., Patel, R. J., Gaur, M., Parikh, S. & Prajapati, B. G. Metallic and metal oxide nanoparticles in treating Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 91, 105290 (2024).

-

Ge, L. et al. Nanosilver particles in medical applications: synthesis, performance, and toxicity. Int. J. Nanomed. 9, 2399–2407 (2014).

-

Synthesis of silver. nanoparticles: chemical, physical and biological methods – Cerca con Google. https://www.google.com/search?q=Synthesis+of+silver+nanoparticles%3A+chemical%2C+physical+and+biological+methods&rlz=1C5CHFA_enIT935IT936&oq=Synthesis+of+silver+nanoparticles%3A+chemical%2C+physical+and+biological+methods&gs_lcrp=EgZjaHJvbWUyBggAEEUYOdIBBzc1MWowajeoAgCwAgA&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8.

-

Leonardi, A. A. et al. Molecular fingerprinting of the omicron variant genome of SARS-CoV-2 by SERS spectroscopy. Nanomaterials 12, 2134 (2022).

-

Khodashenas, B. & Ghorbani, H. R. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles with different shapes. Arab. J. Chem. 12, 1823–1838 (2019).

-

Cheng, Z. et al. Application of serum SERS technology based on thermally annealed silver nanoparticle composite substrate in breast cancer. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 41, 103284 (2023).

-

Richard, A. & Corà, F. Influence of dispersion interactions on the polymorphic stability of crystalline oxides. J. Phys. Chem. C Nanomater Interfaces. 127, 10766–10776 (2023).

-

Rafique, M., Sadaf, I., Rafique, M. S. & Tahir, M. B. A review on green synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their applications. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 45, 1272–1291 (2017).

-

Dong, Q. & Jiang, Z. Platinum–Iron nanoparticles for oxygen-enhanced sonodynamic tumor cell suppression. Inorganics 12, 331 (2024).

-

Chelly, M. et al. Optimization of ZrO2-based electrode materials for simultaneous electrochemical sensing of dopamine, uric acid and tyrosine. Mater. Today Commun. 45, 112254 (2025).

-

Rahbarnia, L. et al. Current trends in targeted therapy for drug-resistant infections. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 103, 8301–8314 (2019).

-

Lin, D. M., Koskella, B. & Lin, H. C. Phage therapy: an alternative to antibiotics in the age of multi-drug resistance. World J. Gastrointest. Pharmacol. Ther. 8, 162–173 (2017).

-

Jahandar-Lashaki, S. et al. Phage display as a medium for target therapy based drug discovery, review and update. Mol. Biotechnol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12033-024-01195-6 (2024).

-

Chang, C. et al. Engineered M13 phage as a novel therapeutic bionanomaterial for clinical applications: from tissue regeneration to cancer therapy. Mater. Today Bio. 20, 100612 (2023).

-

Wang, H. et al. Phage-based delivery systems: engineering, applications, and challenges in nanomedicines. J. Nanobiotechnol. 22, 365 (2024).

-

Zhao, H. et al. Phage display-derived peptides and antibodies for bacterial infectious diseases therapy and diagnosis. Molecules 28, 2621 (2023).

-

Pung, H. S., Tye, G. J., Leow, C. H., Ng, W. K. & Lai, N. S. Generation of peptides using phage display technology for cancer diagnosis and molecular imaging. Mol. Biol. Rep. 50, 4653–4664 (2023).

-

De Plano, L. M., Oddo, S., Guglielmino, S. P. P., Caccamo, A. & Conoci, S. Generation of a helper phage for the fluorescent detection of peptide-target interactions by dual-display phages. Sci. Rep. 13, 18927 (2023).

-

De Plano, L. M., Oddo, S., Bikard, D., Caccamo, A. & Conoci, S. Generation of a biotin-tagged dual-display phage. Cells 13, 1696 (2024).

-

De Plano, L. M. et al. Phage-based assay for rapid detection of bacterial pathogens in blood by Raman spectroscopy. J. Immunol. Methods. 465, 45–52 (2019).

-

Tian, L. et al. Self-assembling nanofibrous bacteriophage microgels as sprayable antimicrobials targeting multidrug-resistant bacteria. Nat. Commun. 13, 7158 (2022).

-

Rizzo, M. G. et al. A novel serum-based diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease using an advanced phage-based biochip. Adv. Sci. (Weinh). 10, e2301650 (2023).

-

De Plano, L. M. et al. Innovative IgG biomarkers based on phage display microbial amyloid mimotope for state and stage diagnosis in alzheimer’s disease. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 11, 1013–1026 (2020).

-

Paramasivam, K. et al. Advances in the development of phage-based probes for detection of bio-species. Biosensors 12, 30 (2022).

-

Jin, P. et al. A blood circulation-prolonging peptide anchored biomimetic phage-platelet hybrid nanoparticle system for prolonged blood circulation and optimized anti-bacterial performance. Theranostics 11, 2278–2296 (2021).

-

Olesk, J. et al. Antimicrobial peptide-conjugated phage-mimicking nanoparticles exhibit potent bactericidal action against Streptococcus pyogenes in murine wound infection models. Nanoscale Adv. 6, 1145–1162 (2024).

-

Iglesias, E. & Brandariz, I. A further study of acetylacetone nitrosation. Org. Biomol. Chem. 11, 1059–1064 (2013).

-

Morganti, D. et al. Zirconia/Graphene oxide composites for improved electrochemical sensing of tyrosine. In Sensors and Microsystems (eds Conoci, S. et al.) 152–159 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-82076-2_22 (Springer Nature Switzerland, 2025).

-

Giuffrida, S., Ventimiglia, G. & Sortino, S. Straightforward green synthesis of naked aqueous silver nanoparticles. Chem. Commun. 4055–4057. https://doi.org/10.1039/B907075C (2009).

-

Abkhalimov, E., Ershov, V. & Ershov, B. Determination of the concentration of silver atoms in hydrosol nanoparticles. Nanomaterials (Basel). 12, 3091 (2022).

-

Paramelle, D. et al. A rapid method to estimate the concentration of citrate capped silver nanoparticles from UV-visible light spectra. Analyst 139, 4855–4861 (2014).

-

Benito, A., Ventoura, G., Casadei, M., Robinson, T. & Mackey, B. Variation in resistance of natural isolates of Escherichia coli O157 to high hydrostatic pressure, mild heat, and other stresses. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65, 1564–1569 (1999).

-

Wang, H. et al. NIR-II AIE luminogen-based erythrocyte-like nanoparticles with granuloma-targeting and self-oxygenation characteristics for combined phototherapy of tuberculosis. Adv. Mater. 36, 2406143 (2024).

-

Zhang, Z., Wang, L., Guo, Z., Sun, Y. & Yan, J. A pH-sensitive imidazole grafted polymeric micelles nanoplatform based on ROS amplification for ferroptosis-enhanced chemodynamic therapy. Colloids Surf. B. 237, 113871 (2024).

-

Takáč, P. et al. The role of silver nanoparticles in the diagnosis and treatment of cancer: are there any perspectives for the future?? Life (Basel). 13, 466 (2023).

-

De Plano, L. M. et al. Phage-phenotype imaging of myeloma plasma cells by phage display. Appl. Sci. 11, 7910 (2021).

-

Scibilia, S. et al. Self-assembly of silver nanoparticles and bacteriophage. Sens. Bio-Sensing Res. 7, 146–152 (2016).

-

Afshinnia, K. & Baalousha, M. Effect of phosphate buffer on aggregation kinetics of citrate-coated silver nanoparticles induced by monovalent and divalent electrolytes. Sci. Total Environ. 581–582, 268–276 (2017).

-

Wang, D., Tejerina, B., Lagzi, I., Kowalczyk, B. & Grzybowski, B. A. Bridging interactions and selective nanoparticle aggregation mediated by monovalent cations. ACS Nano. 5, 530–536 (2011).

-

Ojea-Jiménez, I. & Puntes, V. Instability of cationic gold nanoparticle bioconjugates: the role of citrate ions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 13320–13327 (2009).

-

Souza, G. R. et al. Networks of gold nanoparticles and bacteriophage as biological sensors and cell-targeting agents. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 103, 1215–1220 (2006).

-

Butler, J. C., Angelini, T., Tang, J. X. & Wong, G. C. L. Ion multivalence and like-charge polyelectrolyte attraction. Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 028301 (2003).

-

Putra, B. R. et al. Bacteriophage M13 aggregation on a microhole poly(ethylene terephthalate) substrate produces an anionic current rectifier: sensitivity toward anionic versus cationic guests. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 3, 512–521 (2020).

-

Laghi, G. et al. Control strategies for atmospheric pressure plasma polymerization of fluorinated silane thin films with antiadhesive properties. Plasma Processes Polym. 20, 2200194 (2023).

-

Bjellqvist, B. et al. The focusing positions of polypeptides in immobilized pH gradients can be predicted from their amino acid sequences. ELECTROPHORESIS 14, 1023–1031 (1993).

-

Lentini, G. et al. Phage–AgNPs complex as SERS probe for U937 cell identification. Biosens. Bioelectron. 74, 398–405 (2015).

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

41598_2025_5069_MOESM1_ESM.doc

Supplementary Material 1 NOTE: The file present in the link below is not corrected. PLEASE CONTACT THE MAIN AUTHOR at sabrina.conoci@unime.it for the correct file!

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

De Plano, L.M., Morganti, D., Nicotra, G. et al. Engineered phage-silver nanoparticle complexes as a new tool for targeted therapies. Sci Rep 15, 36135 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05069-y

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05069-y