Introduction

Transient delivery vehicles have garnered substantial attention in biomedicine, showcasing their efficacy in applications ranging from vaccines to gene therapy1,2,3. These vehicles offer a short-term transgene expression window, enabling fine regulation and mitigating potential immune responses and side effects associated with transgene products4,5. Among them, virus-like particles (VLPs), harnessing the advantageous characteristics of both viral and non-viral vectors, emerge as promising candidates for transient gene delivery. Current VLPs have demonstrated efficient delivery in the liver through systemic administration, as well as in the eyes and brain through in situ administration6,7,8,9, and have already been used in clinical trials10. However, despite their notable achievements, a significant obstacle hindering further advancements is the limited tropisms, resulting in ineffective delivery to specific tissues, notably the central nervous system. Approaches such as pseudotyping or incorporating specific peptides have been employed to broaden their targeting capabilities, showing the potential of VLPs to serve as programmable vehicles11,12. Addressing the constraints associated with VLP vectors, we aimed to develop a programmable VLP vector with tailored tropisms through engineering the envelope proteins of the vector. However, current retrovirus-based VLPs, which require multiple viral proteins for assembly and the transgene delivery process, mean a serious engineering challenge and high system complexity. To overcome this challenge, we decided to customize a streamlined VLP backbone with minimal viral elements, using the positive-strand RNA virus Semliki Forest Virus (SFV) as the backbone.

SFV is a member of the Togaviridae family and Alphavirus genus. SFV virus particles are ~70 nm in diameter and are enveloped. The SFV capsid is an icosahedral structure formed by 240 copies of the capsid protein, with a diameter of about 40 nm, containing a single-stranded positive-sense RNA genome of ~11.8 kb13,14. The genome has two open reading frames (ORFs) encoding four non-structural proteins (nsP1-nsP4) and structural proteins (capsid and E3-E2-6K/TF-E1). Its envelope proteins form heterodimers of E1 and E2, which assemble into (E1/E2)3 trimeric spikes, with 80 spikes on the viral envelope facilitating binding to target cell receptors and membrane fusion15,16. The primary receptors mediating SFV entry into target cells are the very low-density lipoprotein receptor (VLDLR) and apolipoprotein E receptor 2 (ApoER2), with VLDLR binding to the E1 protein playing a crucial role in this process17,18. SFV-based vectors have shown promise in preclinical and clinical studies for cancer therapy due to their broad targeting ability and oncolytic properties19,20. Based on its natural tropism for the nervous system, it is a potential candidate for gene therapy delivery to neural tissues, demonstrating significant efficacy in mice and rats21,22,23,24.Besides, alphaviruses, including SFV, have also been utilized in vaccine research25,26,27,28.

In this study, we use SFV as a backbone to streamline the VLP system and develop a VLP vector with programmable targeting capabilities through strategic engineering of its envelope proteins via rational peptide insertion or pseudotyping, thereby broadening its targeting capabilities.

Results

Customization and simplification of the SFV-based VLP system

Considering the composition of the delivery vectors and the natural life cycle of viruses, we optimized a positive-strand RNA virus as the backbone. Based on a phylogenetic analysis of RNA viruses and taking into account factors such as genome size, immunogenicity, and ease of genetic manipulation29,

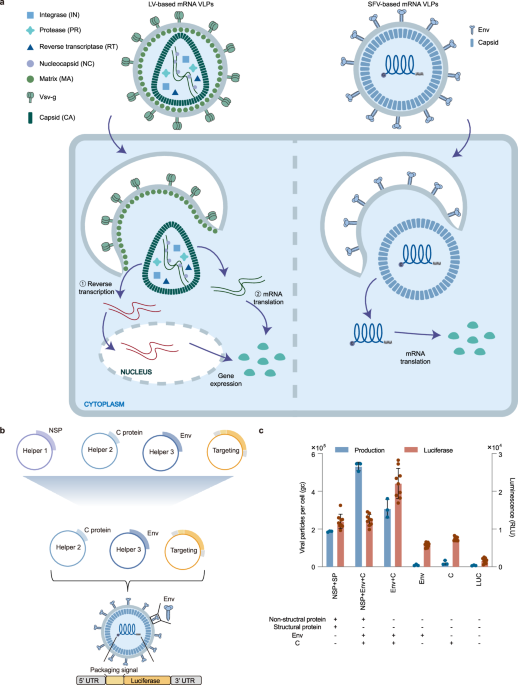

we ultimately chose an alphavirus from the Togaviridae family—specifically, Semliki Forest Virus (SFV) of the Martellivirale order—for further engineering (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 1).

a Composition and transgene delivery mechanisms of mRNA VLPs based on two distinct RNA viruses: lentivirus (LV-based mRNA VLPs, left) and SFV (SFV-based mRNA VLPs, right). SFV-based mRNA VLPs are streamlined, requiring only viral capsid (CA) and envelope proteins for the packaging and translation of mRNA. In contrast, LV-based mRNA VLPs necessitate additional viral proteins such as reverse transcriptase (RT), protease (PR), integrase (IN), nucleocapsid (NC), and matrix (MA), in addition to capsid and envelope proteins. Notably, some lentivirus-based mRNA VLPs require reverse transcription of RNA into cDNA and subsequent nuclear import for transgene expression (process ①), while others (process ②), like SFV-based VLPs, facilitate direct translation. b Construction and simplification of the VLP vector. The initial packaging included non-structural protein (NSP) as one of the helpers, a component eliminated in the final simplified packaging system. c Packaging and delivery efficiency with different packaging systems. The luciferase mRNA was packaged using different packaging systems. Packaging efficiency was assessed by the number of VLP genomic copies per cell, whilst delivery efficiency is measured by measuring the luminescence intensity of the produced luciferase. VLP genomic copies (n = 3) and luminescence (n = 9) in delivered BHK-21 cells were assessed. The left y-axis illustrated packaging efficiency, represented by the quantity of produced VLP per cell. The right y-axis depicted in vitro delivery efficiency, measured by luminescence intensity in the delivered cells. Error bars represented the mean with standard deviation (SD) of independent replicates. Statistical analysis details were provided in the Supplementary Data 1. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To reduce engineering challenges and potential safety concerns, we minimized virus-derived components. To achieve a minimum viral composition of the VLP vector both in the delivered cargo and the protein shell, we completely deleted all viral protein-coding sequences and replaced them with transgene, ensuring that the mRNA cargo contained only a minimal amount of viral sequences associated with the capsid C protein binding. As for the shell, it only included C proteins for cargo binding and envelope proteins for targeting (Fig. 1b). Given alphaviruses have been reported self-assembling capability30,31, we also simplified the packaging process, minimizing the theoretical risk associated with carrying viral coding sequences from recombination events by eliminating the participation of viral non-structural proteins (NSPs) in the packaging process (Fig. 1c). The results showed that the absence of NSPs did not hinder VLP packaging and delivery compared with the presence of NSPs as the helper, indicating NSPs were not necessary for the process of VLP packaging and delivery and only the envelope and C proteins were essential for vector assembly and function.

Transient in vitro delivery efficiency

We then evaluated the RNA and protein production windows of the VLP vector on cell lines. We monitored the duration of the delivered reporter luciferase at different time points after delivery. The results showed that both RNA and protein were produced within 2 h post-delivery, with transient RNA and produced protein lasting up to 96 h (Fig. 2a). We also validated the delivery efficiency of the VLP vector on different cell lines. The VLP vector exhibited a dose-dependent manner across various human (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 2a) and rodent cell lines (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 2b) derived from different organs, showing broad-spectrum in vitro delivery capabilities. We further compared the delivery efficiency of the VLP vector with commercial Lipofectamine™ and adeno-associated virus 9 (AAV9) vectors in vitro. Cell lines were categorized based on the performance of liposomal transfection: high transfection efficiency cell lines (e.g., HEK293T), moderate transfection efficiency cell lines (e.g., Huh7, HepG2), and hard-to-transfect cell lines (e.g., THP-1, MRC-5). In high transfection efficiency cell lines, the VLP vector demonstrated higher delivery efficiency compared to the AAV9 vector, but lower than that of the Lipofectamine™ (Supplementary Fig. 3a). In moderate transfection efficiency cell lines, the VLP vector maintained higher efficiency than the AAV9 vector and comparable efficiency to the Lipofectamine™ (Supplementary Fig. 3b, c). In hard-to-transfect cell lines, the VLP vector outperformed both the AAV9 vector and the Lipofectamine™ in terms of delivery efficiency (Supplementary Fig. 3d, e).

a In vitro RNA and protein production duration after delivery. Protein synthesis and RNA copies were assessed at various time points post-delivery. The left y-axis illustrated protein synthesis in delivered cells through luminescence intensity, and the right y-axis indicates RNA copies in delivered cells. b In vitro delivery efficiency on human-derived cell lines. The luciferase mRNA containing vector’s delivery efficiency was evaluated at different vector genomic copies per cell ranging from 100 to 100,000. The y-axis depicted logged luminescence intensity in the delivered cells. c In vitro delivery efficiency on rodent-derived cell lines. The efficiency was assessed at varying vector genomic copies per cell from 100 to 100,000. The y-axis depicted logged luminescence intensity in the delivered cells. d Packaging capability for mRNA cargos. Different-length cargos (top) were packaged, and VLP genomic copies were quantified to represent packaging efficiency (bottom). (GFP vs. Cre, *P = 0.0163; Cre vs. spCas9-Csy4-sg *P = 0.0433). Statistical analyses were performed using one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test. e VLP vector-mediated delivery of protein cargos in vitro. C protein or truncated C protein (Cd118) linked with luciferase by Furin (FUR) or Cathepsin L (CTSL) cleavable peptides. f Predicted structures of Luc-VLP. Luciferase was shown in bright orange. Furin cleavable peptides were shown in purple. C protein and truncated C protein were shown in sky-blue. The structures were predicted by AlphaFold2 ColabFold with MMseqs233,34. g Luminescence intensity of Luc-VLP at 10 ng per well was measured in delivered cells at different time points. Statistical analysis details were provided in Supplementary Data 1. h Negative-stain transmission electron microscopy (TEM) of VLP particles packaging mRNA with various sizes and protein cargos. Scale bar = 50 nm. All error bars represented the mean with standard deviation (SD) of three independent replicates. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

VLP carries diverse cargo without shape change

The natural SFV genome is ~11.8 kb in size, so our SFV-based VLP vector theoretically has an mRNA cargo size limit of about 10 kb. To assess the VLP vector’s packaging capacity for mRNA cargo, we constructed delivered genes of different lengths, ranging from 500 bp for GFP to 10 kb for CRISPRoff tool32. The VLPs packaging efficiency of these cargo was tested. Efficient packaging was observed for all cargo sizes, demonstrating the vector’s packaging versatility (Fig. 2d). We further validated the integrity of VLP-packaged genomes carrying 5.6 kb, 8.9 kb, and 9.2 kb mRNA cargos by Sanger sequencing, and confirmed the full-length sequences of the 5.6 kb and 9.2 kb cargos using PacBio long-read sequencing, thereby demonstrating successful packaging and the completeness of mRNAs at these lengths (Source Data). Beyond mRNA cargo, we further investigated whether the VLP vector could also deliver protein cargo. We linked the capsid C protein with luciferase through a protease cleavable peptide to form fusion proteins and then packaged the Luc-VLP vector to test the delivery efficiency in vitro. According to previous studies, the 1-118 amino acids of the N-terminus of C protein played a role in binding genome RNA, so we considered that deleting this part may contribute to the assembly of Protein-VLP. We chose two proteases, Furin (FUR) and Cathepsin L (CTSL), cleavable linker peptides for validation, and linked luciferase with full-length C protein and truncated C protein (Cd118) separately (Fig. 2e). Additionally, predicted structures, as generated by AlphaFold2 ColabFold with MMseqs233,34, also suggested that truncated C protein might contribute to the formation of a more compact conformation for fusion proteins, potentially facilitating easier packaging (Fig. 2f and Supplementary Fig. 4). The in vitro results showed successful luciferase delivery to the target cells, with the truncated C protein displaying higher delivery efficiency (Fig. 2g). This increased efficiency may be attributed to the potential interference with capsid assembly caused by the additional space occupied by the fused luciferase. Similarly, we constructed Cre-VLPs by fusing Cre recombinase to the capsid protein. These particles also successfully delivered functional Cre protein in vitro, as indicated by recombinase activity (Supplementary Figs. 5–7). Given that ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes are widely used for gene editing applications8,35, we next investigated whether the SFV-VLP platform could deliver CRISPR-Cas9 RNPs. Using a similar strategy as for protein cargo delivery, we fused Cas9 to the truncated C protein and co-packaged it with sgRNA targeting the DsRed gene. The resulting Cas9/sg.DsRed-VLPs were applied to a DsRed-expressing cell line to evaluate knockout efficiency. Next generation sequence data revealed a dose-dependent indel ratio at DsRed locus, confirming the ability of SFV-VLPs to mediate functional RNP delivery (Supplementary Figs. 8–10).

Using negative-staining transmission electron microscopy (TEM), we measured the particle diameters of VLPs packaging mRNA cargos of different lengths and protein cargos. We found that regardless of the type or size of the cargo, the shape and size of the VLP particles did not vary significantly. Nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) also revealed no differences in the diameters of VLPs loaded with different cargos. These results highlight the structural uniformity of VLPs across diverse cargo types. (Fig. 2h and Supplementary Fig. 11, Supplementary Data 2).

These results highlighted the vector’s ability to deliver mRNA cargo up to 10 kb without packaging decrease and could also deliver protein cargo through truncated C protein, all without changes in VLP particle shape or size.

Immune responses in mice and prevalence of pre-existing antibodies

Previous studies have indicated that much of the immunogenicity of SFV arises from its non-structural proteins (NSPs)36. To determine whether the deletion of NSPs reduces immunogenicity, we compared the immune response induced by mRNA VLP vectors either containing or lacking NSPs. Expression levels of viral response–associated genes, including RIG-I, MDA5, IFNA, and IFNB1, were evaluated in transduced cells. The results showed that VLPs lacking NSPs elicited significantly lower expression of immune-related genes compared to those carrying NSPs (Supplementary Fig. 12), suggesting reduced immunogenicity with the minimal VLP configuration. We next assessed the immune response elicited by VLPs in vivo and examined the potential prevalence of pre-existing antibodies in the human population. To assess the immunogenicity of the VLP vector in mice, we first measured the antibodies induced by intravenously (i.v.) injected VLP. We collected serum from mice one day before intravenous administration and at two-, four-, and six-week post-administration to measure neutralizing antibodies (Nab) against VLP. Similar to most viral vectors and virus-derived vectors, intravenous injection of the VLP vector induced the production of neutralizing antibodies37, with high titers two weeks post-injection, decreasing over time, and reaching lower levels by six weeks post-injection (Supplementary Figs. 13 and 14a). To evaluate whether re-administration was feasible, we performed a second injection six weeks after the initial dose. The results showed that despite the low level of neutralizing antibodies six weeks after the first injection, the second administration was ineffective, similar to other virus-derived delivery vectors38,39 (Supplementary Fig. 14b). To assess the prevalence of pre-existing antibodies to SFV-based VLP in the human population, we conducted neutralizing antibody assays against VLP with commercial intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) and pooled human serum. The results showed that no neutralizing antibodies to SFV-based VLP were detected in either IVIG or pooled human serum. This indicated that our SFV-based VLP may have a lower prevalence of pre-existing antibodies in the population, potentially enabling broader patient coverage (Supplementary Fig. 14c, d). We also assessed the expression levels of inflammatory cytokines in the liver and spleen of mice after single or repeated administrations, based on mRNA transcript levels. The results showed that, compared to the PBS-injected group, the expression levels of most inflammatory cytokines did not increase in mice given a single or repeated administration, however, some changes were observed, including upregulation of Serpine1, Il15, and Ccl3 in the spleen, as well as Serpine1 in the liver, while Ccl2 and Ccl8 were downregulated in the spleen (Supplementary Fig. 15).

To validate whether VLP could induce severe immune responses in mice, we monitored the biochemistry via intravenous injection (5 ×1012 genomic copies [gc] per mouse), and histology of mice administered VLP vector through intravenous (5 ×1012 gc per mouse), intracerebroventricular (i.c.v.) (3 ×1010 gc per mouse), and intrathecal (i.t.) injections (6 ×1010 gc per mouse). For intravenous administration, we validated the serum biochemical parameters at different time points after administration to determine whether there was severe liver and kidney damage. The results showed that the serum biochemistry for liver and kidney damage in mice was constantly at normal levels (Supplementary Fig. 16a–f). The minimal tissue damage evaluated by hematoxylin and eosin stained (H&E) tissue sections also demonstrated little tissue damage (Supplementary Fig. 16g). We then investigated whether in situ administration in the central nervous system (CNS) would elicit strong inflammation and damage. After intracerebroventricular or intrathecal administration, tissue damage was examined in mice. The results showed that except for minor tissue damage due to the way of administration, there was little inflammatory response to the VLP vector (Supplementary Fig. 17a, b). We performed Von Kossa staining on the brain tissues of intracerebroventricularly injected mice for further verification. The results showed no significant calcium deposition or tissue damage in the brain tissues of VLP-injected mice compared to the PBS group (Supplementary Fig. 17c). In addition, expression of neuroinflammatory markers including Il-6, Gfap, Iba1, Il-1a, Il-1b, and Il-10 in brain tissues showed no upregulation in VLP-treated mice relative to controls (Supplementary Fig. 18), further supporting the vector’s safety profile upon CNS administration.

Engineering Env for brain targeting and liver detargeting

Previous studies have demonstrated the CNS infectivity of SFV40, prompting an investigation into the potential use of VLP vector for CNS delivery. The results showed that following intracerebroventricular administration with 3 ×1010 gc per mouse, our VLP vector efficiently targeted nerve cells around the injection path two weeks after administration (Fig. 3a). We then considered whether the VLP vector would remain efficient through intravenously administered with 1 ×1012 gc per mouse. However, two weeks after administration, VLP particles were predominantly accumulated in the liver, with only weak signals in the brain, indicating limited blood-brain barrier (BBB) penetration although they could efficiently deliver to nerve cells (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 19). We further considered whether the VLP vector could be engineered to enhance blood-brain barrier crossing and reduce liver accumulation. To achieve this goal, we analyzed the structure of the envelope protein, especially E1 protein of SFV and its receptor VLDLR17. According to previous studies, K345 and K347 of E1 DIII played an important role in forming a salt bridge with D139 of LA3 during SFV-VLDLR binding process18. Therefore, we proposed that interpreting the binding between E1 and VLDLR by rationally inserting a BBB penetrating peptide could both improve crossing BBB and detarget the liver (Fig. 3c). We constructed the variants with peptides insertion in E1, which included peptides from native proteins or screened by phage display, as well as antibody fragments targeting receptors in cerebrovascular endothelial cells, respectively41,42,43 (Supplementary Data 3). We screened all the variants to assess their neuron-delivering ability on mouse neural cell lines. While most of the variants decreased the efficiency in vitro, three candidates, Env-P5 (TGNYKALHPHNG), Env-P11 (VAARTGEIYVPW), Env-N7 (VQQLTKRFSL) were selected depending on their performance (Supplementary Fig. 20a, b). We further established and evaluated the penetration of the selected variants using an in vitro mouse BBB model with mouse cerebral endothelial cells (bEnd.3) and neural cells N2a44. To confirm the integrity and leakage-free status of the BBB model, we assessed transendothelial electrical resistance (TEER), tight junction markers (Claudin-5 and Zo-1), and dextran permeability (Supplementary Fig. 20c and Supplementary Data 4). We then utilized this model to evaluate the BBB-crossing efficiency of Env-P5, Env-P11, and Env-N7 (Supplementary Fig. 20d). While one of the variants demonstrated slightly higher efficiency, the differences compared to the original VLP were not statistically significant. Given the potential disparities between in vitro and in vivo performance, we proceeded to assess the in vivo efficiency of the selected variants in mice. We used luciferase as a reporter gene to determine the real-time distribution of VLP particles after intravenous administration (Fig. 3d–g and Supplementary Fig. 21). The results indicated that one of the variants, Env-P11, exhibited increased accumulation in the central nervous system and reduced presence in the liver compared to the original VLP, achieving up to a 7–8-fold reduction in liver accumulation and a 10-fold enhancement in brain targeting (Supplementary Fig. 22).

a Ai9 mice were intracerebroventricularly injected with 3 ×1010 gc Cre mRNA containing VLP SFV-Env, and tdTomato signal in the brain was assessed two weeks after administration. Immunofluorescence staining for evaluation of tdTomato (green) signals in the brain. DAPI (blue) was used for nuclear staining (whole brain section: scale bar = 800 μm; magnified region: scale bar = 100 μm). b Ai9 mice were intravenously injected with 1 ×1012 gc Cre mRNA containing SFV-Env or PBS, and tdTomato signals in the liver was examined two weeks after administration. Immunofluorescence staining for evaluation of tdTomato (green) signals in the liver. DAPI (blue) was used for nuclear staining (scale bar = 50 μm). c The structure of Env E1 (pine green) binding with VLDLR (violet). K345 and K347 of E1 were shown in wheat and D135 and D137 of VLDLR were shown in purple blue (PDB: 8IHP). d C57 mice were intravenously injected with 1 ×1012 gc luciferase mRNA containing original VLP (SFV-Env) or engineered VLP (Env-P11). Four animals per group. e Animals in images from left to right: one background mouse and four injected mice. The dorsal views of in vivo luminescence imaging for liver targeting efficiency at various times post-injection. The ventral views of in vivo bioluminescence imaging for brain targeting efficiency at various times post-injection. The rainbow images showed the relative levels of luminescence ranging from high (red) to low (blue). Quantification of bioluminescence in the f liver (***P = 0.0005 at 8 h and ****P < 0.0001 at 2 h, 4 h, and 24 h) and g brain (*P = 0.0151 at 24 h and ****P < 0.0001 at 4 h, 6 h, and 8 h) for SFV-Env (black) and Env-P11 (pink). Error bars represented the mean with standard deviation (SD) of four animals. Statistical analyses were performed using two-way ANOVA with Šidák’s multiple comparison test. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We further investigated the biodistribution and blood-brain barrier penetration ability of Env-P11 in mice. First, we performed fluorescence imaging on different organs of Ai9 mice injected with 1 ×1012 gc Cre mRNA containing VLPs. The results showed a dramatic decrease in Env-P11 accumulation in the liver and a stronger fluorescence signal in the brain two weeks after injection, with no noticeable fluorescence signals observed in other tissues (Fig. 4a). Further immunofluorescence and statistical analysis of various tissues confirmed that Env-P11 had reduced liver targeting and enhanced brain delivery efficiency (Fig. 4b, c and Supplementary Fig. 23). Next, we examined the types of neural cells targeted by Env-P11 for enhanced delivery. We intravenously injected SFV-Env and Env-P11 vectors carrying Cre mRNA into Ai9 mice and co-stained tdTomato signals along with the neuronal marker NeuN and the glial cell marker glial fibrillary acidic protein (Gfap). The results demonstrated that Env-P11 exhibited higher tdTomato fluorescence intensity in both NeuN-positive neurons and Gfap-positive glial cells (Fig. 4d, e).

a Ai9 mice were intravenously injected with 1 ×1012 gc Cre mRNA containing original VLP (SFV-Env, n = 3) or engineered VLP (Env-P11, n = 4). Scale representing relative levels of fluorescence from high to low (yellow to red). b Liver tdTomato expression was examined by immunofluorescence (tdTomato, green; DAPI, blue; scale bar = 50 μm). c Calculation of the ratio of positive tdTomato cells in different organs. Data represented the mean with standard deviation (SD) of three independent animals and three fields per organ (Brain: PBS vs. SFV-Env, **P = 0.0068; PBS vs. Env-P11 and SFV-Env vs. Env-P11, ****P < 0.0001. Liver: PBS vs. Env-P11, **P = 0.0088; PBS vs. SFV-Env and SFV-Env vs. Env-P11, ****P < 0.0001. Spleen: PBS vs. SFV-Env and SFV-Env vs. Env-P11, ****P < 0.0001; two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test). Co-immunofluorescence staining of tdTomato with d neuronal marker NeuN or e glial marker Gfap. (NeuN or Gfap, red; tdTomato, white; DAPI, blue; scale bar = 50 μm). Binding ability of VLP vectors to mouse neural cell lines f N2a (****P < 0.0001), g bEnd.3 (****P < 0.0001), and h C8-D1A (****P < 0.0001), and primary cells i primary pericyte (**P = 0.0046), j primary microvascular endothelial cell (EC) (*P = 0.0429), and k primary astrocyte (***P = 0.0001), with vector genomic copies per cell of 100,000, normalized using Gapdh. Error bars represented the mean with SD of four independent replicates. Statistical analyses were performed using two-tailed unpaired t test. l Construction of blood-brain barrier spheroids using primary mouse brain microvascular endothelial cells, primary brain microvascular pericytes, and primary astrocytes45,117. Spheroids were co-incubated with VLPs containing luciferase mRNA at vector genomic copies per cell of m 10,000,000 or n 30,000,000, and luminescence levels of the BBB spheroids were measured. Error bars represented the mean with SD of three independent replicates (*P = 0.0291, two-tailed unpaired t test). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To assess the BBB penetration capabilities of Env-P11, we conducted multiple tests: evaluating brain vascular leakage caused by the vector, the blood clearance rate of the vector, the binding capacity to cells, and the transcytosis ability. By co-injecting dextran with SFV-Env, Env-P11, or a combination of SFV-Env and Env-P11, we found that mice injected with these vectors showed no signs of potential brain vascular leakage compared to mice with traumatic brain injuries, which served as a positive control (Supplementary Fig. 24). For the blood clearance rate of the vector, we collected blood samples from mice at 1 min, 2 h, 4 h, and 6 h after intravenous injection of SFV-Env or Env-P11 and measured the genomic copy number of the vectors (Supplementary Fig. 25a). We found that the clearance rate of Env-P11 was not significantly different from SFV-Env (Supplementary Fig. 25b). We also collected different tissue samples 4 h post-injection and measured the genomic copy number. The results showed significantly lower accumulation of Env-P11 in the liver and higher accumulation in the brain compared to SFV-Env (Supplementary Fig. 25c). Next, we assessed the binding capacity of VLPs with various mouse neural cell lines and primary cells. We found significantly higher binding capacities in several neural cell lines (N2a, bEnd.3, C8-D1A) (Fig. 4f–h and Supplementary Fig. 25d) as well as in primary mouse brain microvascular endothelial cells (EC), brain microvascular pericytes, and astrocytes (Fig. 4i–k and Supplementary Fig. 25e). Using an established BBB spheroid model45, we verified the transcytosis ability of the vectors (Fig. 4l). When incubating VLPs containing luciferase mRNA with BBB spheroids, Env-P11 exhibited significantly higher luminescence intensity (Fig. 4m, n). Although the difference was not statistically significant, we observed increased RNA copy numbers and protein levels in BBB spheroids co-incubated with Env-P11. At the end of the experiment, no changes in dextran permeability were observed in any VLP-treated spheroids, confirming the integrity of the BBB spheroid barrier (Supplementary Fig. 26). We then used AlphaFold2 ColabFold with MMseqs233,34 to predict the structure of E1 protein of Env-P1117,18,34,46, and found that the inserted peptide affected the binding of E1 protein to VLDLR receptor in spatial position compared with the original E1 protein (Supplementary Fig. 27). This supported the increased ability of Env-P11 to cross the BBB and reduced liver targeting. In conclusion, we developed the VLP vector with programmable tropism by engineering Env proteins as a powerful strategy for enhancing blood-brain barrier crossing and liver detargeting.

Engineering Env for expanded in vitro targeting or muscle tropism

Although the tropism of the VLP vector could be changed by modifying the E1 protein, these changes were still limited to the properties of SFV backbone. Recognizing this limitation, we explored the possibility of overcoming the constraints by pseudotyping VLP for enhancing vector programmability and expanding its targeting capabilities. We initially replaced Env with Vsv-g, the envelope protein of Vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV), and constructed the engineered VLP.Vsv-g47. In vitro efficiency assessments demonstrated VLP.Vsv-g maintained efficacy in a dose-dependent manner, indicating the adaptability of our VLP system by pseudotyping with the envelope protein from other viruses (Fig. 5a). Our above results indicated that SFV-Env had weak delivery efficiency for peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), while studies have shown that lentiviral vectors pseudotyped with Vsv-g achieve higher delivery efficiency for PBMCs48,49. Therefore, we further tested the delivery efficiency of VLP.Vsv-g in PBMCs to verify if the targeting properties had changed. The results showed that VLP.Vsv-g exhibited dramatically higher delivery efficiency both in mouse and in non-human primate PBMCs compared to the original SFV-Env, demonstrating that the targeting capability of the VLPs had indeed undergone programmable changes (Fig. 5b, c). Additionally, biodistribution analysis in Ai9 mice following intravenous injection of VLP.Vsv-g revealed a pattern consistent with other Vsv-g pseudotyped vectors, where VLP particles predominantly accumulated in the liver and, to a lesser extent, in the spleen, with minimal distribution in other organs, such as heart, lung, kidney, and muscle. This observation aligns with previous reports on Vsv-g-based VLP systems6 (Supplementary Fig. 28). In addition to viral envelope proteins, mammalian fusogens have also been used as envelope proteins for gene delivery in recent years11,50. Therefore, we further expanded the concept and considered whether pseudotypes could also directly obtain the capabilities and properties of these proteins. We constructed VLP.Syna by incorporating with Syna, a mammalian placenta-derived fusion membrane protein that has been reported to assemble into VLP for delivery in mammalian cells11. The results showed that VLP.Syna also exhibited dose-responding in vitro efficiency (Supplementary Fig. 29). On the other hand, the modified characteristics of the VLP vector were also evident in its ability to evade neutralizing antibodies induced by SFV-Env. Serum samples collected from re-administered mice two weeks after secondary intravenous administration were used to assess the neutralizing antibody evasion capability of SFV-Env and VLP.Vsv-g. We observed increased levels of neutralizing antibodies against SFV-Env compared to the initial injection. In contrast, VLP.Vsv-g successfully evaded these neutralizing antibodies induced by the original VLP (Fig. 5d–f).

a Env was replaced by Vsv-g and packaging luciferase mRNA containing VLP (VLP.Vsv-g). b In vitro efficiency of VLP.Vsv-g on non-human primate PBMCs with increased VLP genomic copies per cell. NC, negative controls without fusogens. NC of Vsv-g, negative control for VLP.Vsv-g, A549 cells (SFV-Env vs. VLP.Vsv-g at 1000, 10,000, 100,000 copies per cell, ****P < 0.0001; two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test). c In vitro efficiency of VLP.Vsv-g on mouse PBMCs with increased vector genomic copies per cell. NC, negative controls without fusogens. NC of Vsv-g, negative control for VLP.Vsv-g, A549 cells (SFV-Env vs. VLP.Vsv-g at 1000 copies per cell, *P = 0.015; at 10,000 copies per cell, ***P = 0.0001; at 100,000 copies per cell, ****P < 0.0001; two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test). Serum neutralizing antibody evaluation against d SFV-Env and e VLP.Vsv-g in intravenously re-administered animals after the second injection. f Serum neutralizing antibody titers against SFV-Env and VLP.Vsv-g in animals after the second intravenous injection. ND not detected. All error bars represented the mean with standard deviation (SD) of three replicates. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We further replaced Env with muscle-specific mammalian fusogens Myomaker and Myomerger, which were shown to have the capability to form vectors for better muscle delivery50, and constructed VLP.Myok/Myog for in vivo validation. Intramuscular (i.m.) administration of 3.95 ×109 gc Cre mRNA containing VLP.Myok/Myog in mice confirmed transgene production in muscle cells two weeks after administration, demonstrating the potential muscle-targeting capability of the modified VLP vector (Fig. 6a, b). Furthermore, we investigated whether the tropism of the VLP was altered after substitution. The results demonstrated a marked enhancement in muscle targeting following systemic administration with 1 ×1012 gc Cre mRNA containing VLP, consistent with previous findings. The highest delivery efficiency was observed in the diaphragm (~60%), followed by ~30% in the gastrocnemius and quadriceps muscles; no evident signals were detected in other tissues (Fig. 6c–e). These findings collectively indicated that the targeting ability of the VLP vector was modified, confirming its programmability through pseudotyping.

a Env was replaced by Myomaker and Myomerger and packaging Cre mRNA containing VLP (VLP.Myok/Myog). Ai9 mice were intramuscularly (i.m.) injected with 3.95 ×109 gc Cre mRNA containing original VLP (SFV-Env), VLP.Myok/Myog or PBS and tdTomato signals in the muscle was detected two weeks after administration. (Three animals per group.) Immunofluorescence staining for evaluation of tdTomato (green) signals in the muscle. DAPI (blue) was used for nuclear staining (scale bar = 50 μm). b Calculation for the ratio of positive tdTomato cells in a. Error bars represented the mean with standard deviation (SD) of three independent animals and three fields for each animal (PBS vs. VLP.Myok/Myog and SFV-Env vs. VLP.Myok/Myog, ****P < 0.0001). Statistical analyses were performed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test. Ai9 mice were intravascularly injected with 1 ×1012 gc Cre mRNA containing VLP.Myok/Myog and tdTomato signals in the c muscle and d other organs were detected two weeks after administration. Three animals per group. Immunofluorescence staining for evaluation of tdTomato (green) signals in the different tissues. DAPI (blue) was used for nuclear staining (scale bar = 50 μm). e Calculation for the ratio of positive tdTomato cells in c and d. Error bars represented the mean with SD of three (other tissues) or four (muscle) independent animals and three fields for each animal (diaphragm vs. gastrocnemius, quadriceps, heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidney, gastrocnemius vs. heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidney and quadriceps vs. heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidney, ****P < 0.0001). Statistical analyses were performed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Discussion

Transient delivery vehicles have garnered increasing attention in recent years, demonstrating notable achievements across various fields1,2. Among them, VLPs have emerged as promising delivery tools, capitalizing on the advantages of both viral and non-viral vectors, and have shown therapeutic potential in clinical and preclinical studies6,10,51. To date, various types of VLPs for transgene delivery have been developed, including those delivering tumor suppressors, reporter proteins, meganuclease, zinc finger, TAL effector nucleases, clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) associated proteins, base editors, and prime editors6,7,9,51,52,53,54,55,56,57. However, the limited tropism of current VLP vectors poses a significant hurdle to their widespread application. To overcome this limitation, our study focused on developing a programmable VLP delivery system, enabling tailored modifications to achieve VLP vectors with diverse tropisms to specific application requirements.

Selecting the appropriate virus as the VLP backbone was a pivotal decision. Current VLP vectors predominantly rely on retroviruses, such as murine leukemia viruses (MLVs) or lentivirus (LV)6,7,51. However, inherent engineering challenges arise due to the involvement of multiple viral proteins in the assembly and delivery processes58,59,60. Consequently, our objective was to prioritize simplicity for engineering. Therefore, we customized a VLP backbone based on a positive-strand RNA virus. Considering factors of packaging capacity, immunogenicity, and manipulability, Semliki Forest Virus emerged as the ideal backbone for our programmable VLP29,40. In addition to refining the vector’s composition, we streamlined the VLP packaging process limiting it to capsid and envelope proteins while excluding other virus-derived proteins. This method aimed to alleviate potential safety concerns by simplifying the packaging process, eliminating the theoretical risk of replication-competent VLPs emerging from recombination events during production61. As packaging capacity and the type of cargo, similar to current retrovirus-based VLPs, our customized SFV-based VLP exhibited versatility in delivering mRNA, protein, or RNP, with mRNA cargo ranging from 500 bp to 10 kb, meeting the requirements of diverse therapeutic agents. Confirmation of the VLP genomes carrying different mRNA cargo sizes demonstrated the successful packaging of size-matched mRNAs into VLP particles. However, due to the limitations of reverse transcription efficiency with long RNA molecules, cargos exceeding 9 kb were split into two parts for sequencing. Both segments were successfully sequenced, and the results matched the original design. These VLP particles, loaded with different types and sizes of cargo, did not show differences in size or diameter. Negative-staining transmission electron microscopy revealed that the diameter and shape of these VLP particles were slightly smaller the theoretical wild-type SFV virus62. We hypothesize that this discrepancy may result from differences in imaging techniques between cryo-electron microscopy and TEM, a phenomenon that has also been observed in other studies using TEM to examine SFV particles63,64. Similarly, due to differences in sample preparation protocols between NTA and TEM, particularly the dehydration and shrinkage steps required for TEM, the particle diameters measured by TEM tend to be smaller than those obtained by NTA65. By measuring the peak levels of RNA and protein after in vitro delivery, we found that SFV-VLP reached peak RNA and protein expression ~24 h post-delivery. However, there was a mismatch between RNA and protein levels before and after the peak. We speculate that this may be due to two factors: first, differences in the sensitivity of methods used to measure RNA and protein expression; second, variations in cell growth rates at different culture time points, which may lead to discrepancies between mRNA transcription and translation rates. This phenomenon has been observed in both prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells66,67. Therefore, when using in vitro delivery for different target proteins, it is essential to consider the actual peak expression times of both mRNA and protein for each specific protein. Previous studies demonstrated that direct injection of SFV into the brains of rats could lead to severe neural inflammation, potentially caused by viral non-structural proteins, especially nsp-236,40. Consistent with these findings, our results demonstrate that deletion of NSP components from the VLP vector significantly reduces the immune response in cells. In particular, the removal of NSPs led to diminished activation of key innate immune sensors such as RIG-I and MDA5, which are known to recognize 5′-triphosphate RNA and double-stranded RNA from RNA viruses. This reduction in upstream recognition also attenuated the downstream signaling cascades responsible for inducing interferon (IFN) production68,69,70,71,72. By omitting maximal viral elements in the composition of the VLP vector, we aimed to address this safety concern, as evidenced by the limited immune response observed in mice through various routes of administration, including intravenous, intracerebroventricular, and intrathecal injection, underscoring the safety profile of our customized VLP. While this VLP vector, like other viral vectors and virus-derived vectors, induced neutralizing antibodies after intravenous injection, potentially affecting its ability for re-administrations37,38,39, the programmability of the VLP greatly mitigated this issue, as vectors with replaced envelope proteins could evade neutralizing antibodies induced by the original VLP. By replacing the SFV-VLP envelope protein with Vsv-g, we demonstrated that modifying the envelope protein allows the VLP to evade neutralizing antibodies induced by the first SFV-VLP injection. This finding suggests the feasibility of repeated administration of the vector. To evaluate immune responses following single and repeated injections, we measured the expression levels of inflammatory factors in the liver and spleen. The results showed no significant differences in the expression levels of most inflammatory factors compared to the control group. However, some factors exhibited changes that might be related to the suppression of inflammation and innate antiviral immunity. These included an upregulation of Serpine1 RNA levels in both the liver and spleen and a downregulation of Ccl2 and Ccl8 levels in the spleen. These factors play essential roles in inflammatory responses73,74,75,76 and it’s important to promote migration of inflammatory cells by chemotaxis and integrin activation77,78,79. However, the observed upregulation of Il15 and Ccl3 RNA levels in the spleen suggested potential immune cell activation and a virus-induced inflammatory response80,81,82. Ccl3 directs macrophage recruitment and promotes the maturation of CD8⁺ T cells into effector cells, enabling their circulation and subsequent migration to target tissues83. Furthermore, considering the potential impact of existing neutralizing antibodies on future clinical use, we assessed the existing Nab titer of the VLP. SFV-based VLP did not show Nab titers in both commercial IVIG and pooled human serum, suggesting a probable low prevalence of existing neutralizing antibodies in the human population. These results demonstrated the favorable safety profile of our SFV-based VLP, reinforcing its potential for clinical applications.

The programmability of the vector centered on the engineering of envelope proteins, achieved either through rational modification of the envelope proteins or pseudotyping. Previous studies demonstrating SFV’s capability to infect the central nervous system align with our results when VLP in situ was administered into mice brain40, indicating the vector’s promise as a delivery vehicle for the nervous system. However, same as current VLP vectors, SFV-based VLP also tended to accumulate in the liver after intravenous administration, indicating limited blood-brain barrier crossing ability6,8. To enhance this capability, we rationally introduced a peptide at the key binding site of the Env protein and receptor VLDLR, resulting in candidates with improved BBB-crossing ability17,18, particularly Env-P11. For Env-P11, although we did not observe lower clearance rates in the bloodstream, significant changes in particle aggregation within tissues were evident, including a marked reduction in liver accumulation and an increase in cortical brain accumulation. Moreover, Env-P11 demonstrated significantly enhanced binding ability to neuronal cells in vitro, complementing its improved transcytosis capability. Due to the cell-penetrating peptide (CPP) segment’s general ability to increase cell permeability without targeting specificity84,85, its enhanced delivery to various cells of the nervous system suggested that Env-P11 exhibited higher efficiency in crossing the blood-brain barrier and delivering payloads to neuronal systems compared to the unmodified vector.

In this study, we aimed to validate the blood-brain barrier crossing capabilities of our vectors using two different in vitro mouse BBB models: the transwell model and BBB spheroids. Despite Env-P11 demonstrating higher BBB-crossing efficiency in vivo, it did not exhibit superior efficiency in these two in vitro models. This discrepancy may stem from the inherent differences between in vivo and in vitro environments86. Specifically, in the BBB spheroid model, which more closely mimics the in vivo environment, Env-P11 showed better performance compared to the transwell model. Notably, changes in tissue particle distribution were observed in other organs, indicating higher vector particle accumulation, albeit not statistically significant compared to SFV-Env, particularly in the heart and kidneys. However, both organ IVIS imaging and immunofluorescence results did not detect discernible signals in these tissues. This difference may be due to variations in sensitivity between mRNA- and protein-level detection methods. Moreover, protein translation efficiency and stability are influenced not only by the number of mRNA transcripts but also by factors such as RNA structure87, translation regulators88, and post-translational modifications89. The versatility of SFV-based VLP was further extended through pseudotyping, incorporating Vsv-g and mammalian Syna11, demonstrating efficient and expanded in vitro delivery capabilities as well as promising potential for escaping neutralizing antibodies. Furthermore, the incorporation of mammalian muscle-derived fusogens Myomaker and Myomerger conferred its muscle-targeting ability50. These strategies significantly broadened the potential targeting range and enhanced the flexibility of the VLP vector.

Currently, the most widely used in vivo delivery vectors include adeno-associated viruses (AAV), adenovirus (AdV), herpes simplex virus (HSV), and VLP vectors based on LV or MLV. Among these, AAV stands out as the most extensively validated, with broad application across preclinical and clinical studies90. AAV demonstrates high delivery efficiency across various tissues and organs in different mammals, including the heart, liver, spleen, lungs, kidneys, and muscles91. Due to the significant differences between long-term and transient delivery vectors, exact comparisons of delivery efficiency are challenging. In this study, we conducted a head-to-head in vitro comparison of AAV, liposomes, and SFV-Env. The results showed comparable transduction efficiency between liposomes and SFV-Env in most cell lines, with SFV-Env outperforming in hard-to-transfect cells, and both showing higher efficiency than AAV. For in vivo delivery efficiency, it has been reported that AAV8 can achieve 80% delivery efficiency in mouse liver91,92 and AAV9 can achieve about 40% in the brain93,94. In our work, SFV-Env achieved about 70% positive cells in the liver, and Env-P11 achieved about 40% positive cell ratio in the brain, both showing comparable transduction efficiency and potential for further therapeutic applications. Along with our results, we observed some interesting differences between viral vectors and VLP vectors, not only with the SFV-based VLP vector in our study but also with other retrovirus-based VLP vectors. We found that VLP vectors have more targeted and specific delivery capabilities compared to viral vectors, including specific delivery to the liver6, T cells95, and DC cells96. In this study, we also observed that SFV-Env had specific liver-targeting capabilities with minimal off-target effects in other tissues. Env-P11, apart from its enhanced nervous system delivery and reduced liver targeting, did not show significant signals in other tissues either. The further modified VLP.Myok/Myog also showed no off-target signals outside muscle tissues. Most reported LV/MLV-based VLP vectors have been modified for specific targeting needs, possessing unique application requirements and scenarios56,95,96,97. These results suggest that, compared to the broad tropism of viral vectors like AAV and AdV in individuals, the VLP systems may have a higher potential for targeted delivery. Our simplification and development of programmable tropism of the VLP system in this study may contribute to the future applications of other VLP systems.

SFV vectors are known for their high productivity in mammalian cells, particularly in commonly used BHK-21 cells14,98. The predominant method for SFV vector production involves in vitro transcription to generate mRNA for both helper and target RNA, followed by electroporation into BHK-21 cells for vector packaging and production99,100. This approach can yield viral particles ranging from 1 ×109 to 1 ×1010 particles per milliliter101, and efficient production is feasible in serum-free or suspension culture systems102,103. For scalable SFV-based vector production, in vitro transcription of RNA and electroporation are typically regarded as major limiting factors. However, current production strategies also include using adherent BHK-21 and HEK293 cells, or suspension HEK293 cells directly transfected with plasmids for packaging18,104. In this study, we adopted an AAV packaging and purification system previously established in our laboratory105,106, utilizing adherent HEK293T cells with a triple plasmids system for VLP packaging and purification. Further verification of packaging efficiency across various existing production systems and establishment of stringent quality control standards are essential steps to lay the foundation for scale-up production and subsequent clinical applications.

Despite the advances made in this study, two notable limitations should be acknowledged. First, although we successfully delivered Cas9 and sgRNA as a RNP complex and demonstrated reporter gene knockout at the cellular level—a critical feature for CRISPR-based applications8,35—there remains potential to further enhance genome editing efficiency. Strategies such as modulating the ratio between fused Cas9-capsid proteins and non-fused capsid proteins6, optimizing the length and flexibility of the linker between Cas9 and the capsid protein107,108, or employing a dual-VLP system to separately deliver Cas9 protein and sgRNA, may all contribute to improved editing outcomes. Second, while mouse models were employed for both in vitro and in vivo studies on VLP variants in the BBB-crossing screening, the structural differences in the blood-brain barrier between species necessitate further validation in non-human primates (NHPs) for enhanced translational relevance109,110. Subsequent studies will consider the use of NHPs for comprehensive validity verification.

In conclusion, we streamlined the VLP system and developed a programmable VLP vector based on this simplified platform. This approach may be applicable to other low immunogenicity VLPs, enhancing their tropism and efficiency, such as SEND system11. Our programmable VLPs vector, with innovative engineering capabilities, provided a versatile platform for a wide range of treatment strategies (Fig. 7). Its customizability holds promise for advancing therapeutic strategies in the future.

Programmable VLP system based on SFV. The vector demonstrated the capacity to transport both mRNA and protein cargos, with mRNA cargo ranging from 500 bp to 10 kb. Notably, the vector exhibited a transient delivery pattern for both types of cargo. Engineered via rational design, the VLP system allowed modification of its own envelope protein (Env) to facilitate BBB penetration. The VLP could also be engineered by psuedotyping with mammalian-derived fusogens such as Myomaker and Myomerger, endowing the vector with muscle-targeting capabilities. Remarkably, this streamlined VLP system, composed of minimal virus-derived elements, elicited limited immune responses in mice through various administration routes. i.v. intravenous, i.c.v. intracerebroventricular, i.t. intrathecal.

Methods

Ethics statement

All experimental mice were kept in groups, maintained under 12-h light and 12-h dark (12:12 LD) conditions and given food and water ad libitum. All experiments involving animals were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing, and met the ethical and welfare requirements of experimental animals (ethics approval no. IOZ-IACUC-2022-210). Peripheral blood from healthy adult cynomolgus macaques (Macaca fascicularis) sourced from the Beijing Institute of Xieerxin Biology Resource was obtained from an unrelated approved study conducted at the Institute of Zoology. The original study was performed in accordance with all relevant national and institutional guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals (ethics approval no. IOZ-IACUC-2022-167, approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing). No live non-human primate animal procedures were performed specifically for this work.

Cell lines

N2a (Procell, CL-0168), HL-1 (Procell, CL-0605), Renca (Procell, CL-0568), HEK293T(Procell, CL-0005), Hepa 1-6 (Procell, CL-0105), HepG2 (ATCC, HB-8065™), Hep3B (Procell, CL-0102), MRC-5 (Procell, CL-0161), Huh7 (Procell, CL-0120), BHK-21 (BNCC, BNCC339836), C8-D1A (Procell, CL-0506), bEnd.3 (Procell, CL-0598), PANC-1 (Procell, CL-0184) and A549 (ATCC, CCL-185 ™) cells were cultured with Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) (Gibco, 11965084), 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco, 10099141) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco, 15140122). SH-SY5Y (Procell, CL-0208) cells were cultured in MEM/F12 (Procell, PM151220) with 15% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco, 15140122). THP-1 cells (Procell, CL-0233) and A549 (ATCC, CCL-185™) were cultured in RPMI-1640 (ATCC modified, Gibco, A1049101) with 10% FBS, 0.05 mM β-mercaptoethanol and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco, 15140122).

Mouse PBMCs were isolated using the Solarbio P5230 kit and cultured short-term in Mouse Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cell Complete Medium (Procell, CM-M191). Non-human primate PBMCs were separated using Ficoll-Paque PLUS (GE, 17144002) and cultured short-term in Human Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cell Complete Medium (Procell, CM-H182-100).

Primary mouse astrocytes (Procell, CP-M157) were cultured in Mouse Astrocyte Complete Medium (Procell, CM-M157). Primary mouse brain microvascular pericytes (Procell, CP-M222) were cultured in Mouse Brain Microvascular Pericyte Complete Medium (Procell, CM-M222). Primary mouse brain microvascular endothelial cells (Procell, CP-M108) were cultured in Mouse Brain Microvascular Endothelial Cell Complete Medium (Procell, CM-M108).

Animals

Eight-week-old C57BL/6J male mice were supplied by Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd. Ai9 (IMSR_ JAX:00790) mice were the Cre-reporter mice which contained tdTomato red fluorescent reporter gene111.

Laboratory-grade VLP packaging and purification

HEK293T cells were seeded a day before transfection. Lipofectamine™ LTX Reagent and PLUS™ Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 15338100) were used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cell supernatant was collected 48 and 72 h after transfection, combined, and subjected to precipitation with a solution of 40% PEG-8000 and 2.5 M NaCl at a volume ratio of 1:4. After overnight incubation (over 12 h) at 4 °C, the precipitate was isolated by centrifugation at 1500 × g for 30 min at 4 °C. The pellet was resuspended in 10 mL PBS for iodixanol density gradient centrifugation.

Iodixanol density gradient centrifugation

The gradient iodoxanol solution was meticulously prepared within the optimal range (15–60%) using Optiprep™ (Axis-Shield, 1114542) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The sample, resuspended accordingly, was carefully injected into the bottom of the ultracentrifugal tube (Beckman, 344326) using a long needle syringe, and then gradient iodoxanol solution was sequentially injected into the tube in the order of 15%, 25%, 40%, and 60% with volumes of 9 mL, 6 mL, 5 mL, and 5 mL, respectively. The centrifuge tube was capped with mineral oil (Sigma-Aldrich, M8410), and heat-sealed for optimal sealing, followed by centrifuging at 150,000 × g for 2 h at 18 °C using the density gradient centrifugal instrument (Beckman, Optima XPN-100) equipped with a 70 Ti rotor. After centrifugation, the 25% layer was carefully extracted, diluted with PBS, and transferred into centrifugal filter units (Millipore, UFC910096). Centrifugation at 900 × g at 4 °C ensued until the final volume was reduced to less than 2 mL. The concentration step was repeated twice, after which the solution in the filters was extracted, and the copy numbers were subsequently evaluated.

VLP vector titration

QPCR methods of titration for VLP were described before105. In brief, samples were diluted to 300 μL in PBS and RNA genomics were extracted using a kit (Vazyme, RC323-01). RNA genome was reverse-transcripted (Vazyme, R312) and titered by qPCR. Each sample was tested in triplicates. The standard curves in the 20 μL system were linear plasmids of 1 ×1012, 1 ×1011, 1 ×1010, 1 ×109, and 1 ×108 copies, respectively. The qPCR reaction system was established according to the manufacturer’s instructions (AceQ Universal U + Probe Master Mix V2, Vazyme, Q513 or Taq Pro Universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix, Vazyme, Q712). Primer and probe sequences for titration were displayed in Supplementary Data 5. Amplification was performed using QuantStudio 6 Flex real-time PCR systems (Version 1.3) and the copies were calculated using the standard curve.

Mouse PBMC isolation and culture

Mouse PBMCs were isolated using the Peripheral Blood Monocyte Cell Separation Medium Kit (Solarbio P5230). Briefly, blood was collected from the orbital sinus into anticoagulant tubes and diluted with an equal volume of whole blood and tissue diluent or PBS. Density gradient medium was used for separation, and samples were centrifuged at 500 × g for 25 min at room temperature using a horizontal rotor. After centrifugation, distinct layers appeared, and the mononuclear cell layer was carefully collected. The cells were then resuspended in 10 mL of cell wash buffer or PBS, gently mixed by inversion, and centrifuged at 250 × g for 10 min. The supernatant was discarded, and the cell pellet was resuspended in 5 mL of cell wash buffer or PBS, followed by another 250 × g centrifugation for 10 min, repeating the wash step twice. The final pellet was resuspended in complete culture medium (Mouse Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cell Complete Medium, Procell, CM-M191), counted, and seeded at 1 ×104 cells per well in a white/clear 96-well plate (Corning Mediatech, 3903) for short-term culture.

Non-human primate PBMC isolation and culture

Peripheral blood from healthy adult cynomolgus macaques (Macaca fascicularis) was from the Beijing Institute of Xieerxin Biology Resource. PBMCs from non-human primates were isolated using Ficoll-Paque PLUS (GE, 17144002) with a density gradient centrifugation method. Blood samples were centrifuged at 400 × g for 40 min at 18 °C. The mononuclear cell layer was carefully collected and washed twice with PBS, each time centrifuging at 500 × g for 15 min at 18 °C. The final pellet was resuspended in complete culture medium (Human Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cell Complete Medium, Procell, CM-H182-100), counted, and seeded at 1 ×104 cells per well in a white/clear 96-well plate (Corning Mediatech, 3903) for short-term culture.

Detection of in vitro transduction efficiency

Methods of detection of transduction efficiency were described before105. Briefly, cells were seeded with 1 ×104 cells per well into the 96-well white plates (Corning Mediatech, 3903) 24 h before transduction. Luciferase mRNA containing VLP transduced at different vector genomic copies per cell. Luciferase activity was measured 24 h later using a luciferase assay kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Bright-Lite Luciferase Assay System, Vazyme, DD1204).

Construction and simplification of VLPs packaging system

HEK293T cells were seeded in 12-well plates for transfection (5 ×104 cells per well). After 24 h, cells were transfected using Lipofectamine™ LTX Reagent and PLUS™ Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 15338100). The plasmids expressing viral non-structural proteins (NSP), viral structural proteins (SP), viral C proteins (C), and viral envelope proteins (Env) were employed in various combinations. Luciferase-expressing plasmid served as the targeting plasmid. Combinations included NSP + SP, NSP + Env + C, Env + C, Env, and C. Luciferase mRNA containing VLP was then packaged, with supernatant collected at 48 and 72 h after transfection. VLP genomic copy numbers were quantified using the described titration method. BHK-21 cells were employed to assess the delivery efficiency of luciferase mRNA with different components. Cells were co-incubated with vector genomic copies per cell of 100 copies per cell, and luciferase activity was evaluated 24 h after incubation.

Detection of in vitro RNA and protein production duration

BHK-21 cells were seeded into the 96-well white plates with 1 ×104 cells per well. Twenty-four hours later, cells were transduced with luciferase mRNA containing VLP at vector genomic copies per cell of 10,000. RNA copies and activity of luciferase were measured at the point of 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h after transduction, respectively. Luciferase activity was measured as described before. Cellular genomic RNA was extracted with Trizol and an RNA extraction kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen, 12183018A) and titered the copies of luciferase by qPCR as described before.

In vitro comparison of AAV and lipofectamine™ efficiency

Cells were seeded at a density of 1 ×104 cells per well in a white 96-well plate 24 h prior to testing. Twenty-four hours after seeding, cells were infected with AAV with luciferase-expressing cassettes, transfected with plasmids containing luciferase-expressing cassettes via Lipofectamine™, and incubated with VLPs containing luciferase mRNA, based on varying ratios of vector nucleic acid copy numbers per cell. Luminescence intensity in cells was measured 72 h post-AAV infection, 24 h post-Lipofectamine™ transfection, and 12 h post-VLP incubation.

Evaluation of mRNA-VLP packaging efficiency

HEK293T cells were seeded in 12-well plates for transfection. Twenty-four hours later, cells were transfected using Lipofectamine™ LTX Reagent and PLUS™ Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 15338100). The plasmids contained two structural proteins-expressing plasmids (C protein and Env), and one targeting plasmid (GFP, Cre, luciferase. Cas12i-sg112,113, spCas9-tRNA-sg, saCas9-sg, spCas9-Csy4-sg, dCas9-KRAB-MECP2-sg114, and CRISPRoff-sg32, respectively). Each plasmid was packaged in four independent wells. At 48 and 72 h after transfection, supernatant was collected, and VLP genomic copies were titered as described before. The primers sequences were shown in Supplementary Data 5.

Genome sequencing of the mRNA VLPs

VLPs RNA genomes were extracted using an RNA extraction kit (Vazyme, RC323-01), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Reverse transcription was performed using the HiScript III RT SuperMix (Vazyme, R312). The resulting cDNA was subjected to PCR amplification using Q5® High-Fidelity 2× Master Mix (New England BioLabs, M0491L). Target fragments were amplified using forward and reverse primers designed specifically for the cargo regions, with high-fidelity DNA polymerase to ensure sequence accuracy. Primer sequences were detailed in Supplementary Data 5. PCR products were submitted to Tsingke Biological Technology for Sanger sequencing and to GENEWIZ from Azenta Life Sciences for long-read sequencing using the PacBio Sequel platform.

Protein-VLPs packaging and validation

Target proteins (luciferase, Cre, or Cas9) were fused to truncated C protein via cleavable peptides recognized by Furin (FUR) (luciferase or Cre) or Cathepsin L (CTSL) (luciferase or Cas9). HEK293T cells were seeded in 15 cm cell culture dishes a day before transfection. Twenty-four hours after seeding, a total of 40 μg of plasmids encoding the envelope and capsid-linked target proteins were co-transfected using Lipofectamine™ LTX Reagent and PLUS™ Reagent, following the manufacturer’s instructions. Cell supernatants were collected 48 and 72 h after transfection, pooled, and precipitated using a solution of 40% PEG-8000 and 2.5 M NaCl at a volume ratio of 1:4. After overnight incubation (over 12 h) at 4 °C, the precipitate was harvested by centrifugation at 1500 × g for 30 min at 4 °C. The pellet was resuspended in 10 mL PBS for iodixanol density gradient centrifugation.

BHK-21 cells were used for transduction efficiency evaluation. The protein-VLPs (Luc-VLP) were then added into BHK-21 cells as 10 ng per well in 96-well white plates with 1 ×104 cells per well and luciferase activity was evaluated at different time points as described before.

Protein-VLPs titration

For the titration of Protein-VLPs, including Cre-VLPs and Luc-VLPs, both samples and standards were diluted in Carbonate-Bicarbonate Buffer (Sigma, C3041) to the working concentration. Each diluted sample was added to CORNING high binding 96 well polystyrene Microplates (Corning, 42592) at 100 μL per well and incubated with gentle shaking at room temperature for 1 h. After incubation, the liquid was discarded, and the wells were washed five times with 300 μL of Wash Buffer (Pierce™ Concentrated Buffer Stocks, Thermo; 28360), patting dry after each wash. Following the washes, 300 μL of SuperBlock™ Blocking Buffer (Thermo; 37535) was added to each well and incubated with gentle shaking at room temperature for 1 h. The blocking solution was then removed, and the wells were washed again five times using the same washing procedure. Dilute primary antibody (1:4000) was added to 100 μL per well and incubated at room temperature for 2 h. The liquid was discarded and 300ul Wash buffer was added per well. After discarding the antibody solution, wells were washed three times with Wash Buffer. Secondary antibodies (1:5000) were added at 100 μL per well and incubated at room temperature for 2 h, followed by three additional washes. For signal development, 100 μL of 1-Step™ TMB ELISA Substrate Solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific; 34022) was added and incubated in the dark at room temperature for 30 min. The reaction was stopped by adding 100 μL of Stop Solution for TMB Substrates (Abcam; ab171529), and absorbance at 450 nm was measured within 10 min.

Anti-Firefly Luciferase antibody [EPR17790] (Abcam, ab185924) and anti-Cre recombinase antibody [EPR13835] (Abcam, ab188568) were used as primary antibody and goat anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 31460) were used as secondary antibody. Recombinant Bacteriophage P1 Cre recombinase protein (Abcam, ab134845) and Recombinant Firefly Luciferase protein (Abcam, ab100961) were used as standards for the Luc-VLP and Cre-VLP titrations, respectively.

Efficiency determination of Cre-VLP in vitro

Cre-VLPs were packaged and purified as described above. To assess the recombinase activity of Cre, HEK293T cells were seeded in 12-well plate at a density of 2 ×10⁵ cells per well a day before transfection. Twenty-four hours after seeding, Lipofectamine™ LTX Reagent and PLUS™ Reagent were used for transfection according to the manufacturer’s instructions. One microgram of a reporter plasmid (pLV-CMV-LoxP-DsRed-LoxP-eGFP, Miaolingbio, P58767) expressing a loxP-DsRed-loxP-GFP cassette was transfected into each well and 10 ng Cre-VLP were added per well simultaneously. After 48 h of incubation, flow cytometry was performed to analyze GFP and DsRed fluorescence, allowing evaluation of Cre-mediated recombination efficiency using FlowJo software (v10).

CRISPR RNP-VLP packaging and titration

HEK293T cells were seeded in 150 mm cell culture dish a day before transfection. Twenty-four hours after seeding, Lipofectamine™ LTX Reagent and PLUS™ Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 15338100) were used for transfection according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cas9 protein was fused to truncated C protein via cleavable peptides recognized by Cathepsin L (CTSL). A total of 40 μg of plasmids, including 11.91 μg encoding the envelope protein, 14.32 μg encoding the capsid-linked Cas9 protein, and 13.76 μg encoding sgRNA, were co-transfected. Cell supernatants were harvested and purified as described above.

For Cas9/sgRNA RNP-VLPs quantification, ELISA was using FastScan™ Cas9 (S. pyogenes) ELISA Kit (CST, 29666). RNA was extracted using FastPure Viral DNA/RNA Mini Kit (Vazyme, RC323-01) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. Extracted RNA was reverse transcribed using HiScript III 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (+gDNA wiper) (Vazyme, R312) and copy number was determined by qPCR (Taq Pro Universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix, Vazyme, Q712).

Cas9/sg.DsRed-VLP knockout efficiency in vitro

Cas9/sg.DsRed-VLPs were packaged and purified as described above. HEK293T cells were seeded in 12-well plate at a density of 2 ×10⁵ cells per well a day before transfection. Twenty-four hours after seeding, Lipofectamine™ LTX Reagent and PLUS™ Reagent were used for transfection according to the manufacturer’s instructions. One microgram plasmid expressing DsRed cassette was transfected and Cas9/sg.DsRed-VLPs targeting or non-targeting DsRed were added simultaneously (1× Cas9/sg.DsRed-VLP: 4 ×108 gc). Genomic DNA was extracted using the MicroElute Genomic DNA Kit (Omega, D3096-02). The DsRed locus was amplified using Q5® Hot Start High-Fidelity 2X Master Mix (New England BioLabs, M0491L). Primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Data 5. PCR products were submitted to Tsingke Biological Technology for next-generation sequencing. Sequencing data were analyzed using the CRISPResso2 software115, The full-length target region was: GTTCGAGATCGAGGGCGAGGGCGAGGGCAAGCCCTACGAGGGCACCCAGACCGCCAAGCTGCAGGTGACCAAGGGCGGCCCCCTGCCCTTCGCCTGGGACATCCTGTCCCCCCAGTTCCAGTACGGCTCCAAGGTGTACGTGAAGCACCCCGCCGACATCCCCGACTACAAGAAGCTGTCCTTCCCCGAGGGCTTCAAGTGGGAGCGCGTGATGAACTTCGAGGACGGCGGCGTGGTGACCGTGACCCAGGACTCCTCCCTGCAGGACGGCA. The sgRNA target sequence was GGGGTGCTTCACGTACACCT. CRISPResso2 was run with the default_min_aln_score parameter set to 80; all other parameters were left as default. Mutations also found in the non-targeting control group were excluded from downstream analysis. Indel frequencies were recalculated based on filtered reads, and only those with a frequency >0.2% were visualized.

TEM and NTA analysis

Samples of VLP particles, packaged with various cargoes, were sent to Servicebio for TEM and NTA analysis. For TEM analysis, briefly, 20 μL of VLP suspension was loaded onto 200-mesh copper grids coated with a carbon support film (ZB-C1004, ZXBR) and allowed to adsorb for 3–5 min at room temperature. Excess liquid was gently removed using filter paper. The grids were then stained with 2% phosphotungstic acid (Servicebio, G1102) for 1–2 min. After blotting the excess stain, the grids were air-dried at room temperature. Prepared grids were imaged using a HITACHI HT7800 or HT7700 transmission electron microscope. Representative micrographs were captured at magnifications ranging from 30,000× to 80,000×. VLP size distribution were also assessed by NTA using a ZETA-VIEW instrument (Particle Metrix). Instrument calibration was performed prior to sample analysis using 100 nm polystyrene microspheres (Microspheres, 700074) diluted 1:250,000 in ultrapure water (Servicebio, G4701). Samples were diluted in sterile PBS (Servicebio, G4202) to achieve a final particle count in the optimal range of 50–400 particles per frame (ideally ~200). The appropriate dilution factor was input into the analysis software interface. Measurements were performed after confirming consistent particle counts across multiple capture positions. Data were acquired by initiating the software’s “Measurement” and “Run Video Acquisition” functions, followed by entry of sample information and selection of the standard operating procedure (SOP). Particle size (mean, mode, and distribution) and concentration were automatically calculated by the instrument’s software and exported as part of the standard test report.

Animal administrations for in vivo efficiency detection

For in vivo efficiency analysis, eight-week-old C57BL/6J male mice received intracerebroventricular injections at a dose of 3 ×1010 gc per mouse or intravenous injections at a dose of 1 ×1012 gc per mouse. Two weeks post-injection, the mice were euthanized to assess the delivery efficiency across different tissues. All intravenous injection was performed via retro-orbital venous sinus with total volume less than 200 μL. The intracerebroventricular injection was performed using the stereotaxic apparatus and microinjection system with total volume less than 5 μL. The intrathecal injection was performed into the groove between L5 and L6 vertebrate column with total volume less than 10 μL.

Immune responses in single intravenously injected mice

Eight-week-old C57BL/6J male mice were intravenously injected with 5 ×1012 gc VLP vector via retro-orbital venous sinus. Blood samples were collected at −1, 14, 28, and 42 days after injection for neutralizing antibody evaluation and serum biochemistry assessment. At the final time point, animals were sacrificed, and hearts, livers, spleens, lungs, kidneys, and brains were isolated. Portions of liver and spleen tissues were extracted for bulk RNA sequencing and qPCR quantification. The remaining tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde solution for 24 h, followed by embedding, sectioning at 10 μm thickness, and subsequent H&E staining.

In vivo biodistribution of VLPs in Ai9 mice

Eight-week-old Ai9 male mice were i.v. injected with 1 ×1012 gc SFV-Env or 5 ×1012 gc VLP.Vsv-g vector via retro-orbital venous sinus. Two weeks post-injection, the mice were euthanized by CO2 inhalation followed by cervical dislocation. Major organs including the brain, liver, spleen, kidney, and heart were immediately dissected and rinsed in room temperature PBS. Tissues were then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) at room temperature for 24 h, dehydrated through graded ethanol series, cleared in xylene, and embedded in paraffin. Paraffin blocks were sectioned at a thickness of 10 μm using a microtome and mounted on glass slides for histological or immunofluorescence analysis.

In vitro immune response assay

HEK293T or A549 cells were seeded in 48-well plates at a density of 3.5 ×104 cells per well a day before transfection. Twenty-four hours after seeding, cells were transduced with NSP-Cre or Cre mRNA-containing VLPs at vector genomic copies of 10,000 per cell. Total RNA was isolated from cells 24 h after transduction using Trizol and an RNA extraction kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen, 12183018A) and mRNA level of MDA5, RIG-1, IFNA, and IFNB1 were quantified by qPCR as described before. Primer sequences for qPCR were displayed in Supplementary Data 5.

Delivery and antibody response after re-administration

For the re-administration experiment, mice received a second intravenous injection of 5 ×1011 gc VLP vector carrying luciferase mRNA six weeks after the first intravenous administration. Four hours after the second injection, luminescence intensity was measured in vivo by IVIS. Mice were intraperitoneally injected with luciferin at a dose of 100 mg per kg per mouse and anesthetized with 2% isoflurane. Ten minutes after luciferin injection, signals were detected using the Xenogen IVIS200 imaging system, and the data were analyzed with Living Image 4.0 software (Caliper).

Two weeks after the secondary administration, mouse serum was collected to measure neutralizing antibodies against SFV-VLP and VLP.Vsv-g. Following blood collection, the animals were sacrificed, and the livers and spleens were isolated for RNA extraction.

In vitro VLPs neutralization assay

BHK-21 cells were seeded into 96-well white plates a day before transduction. SFV-Env or VLP.Vsv-g containing luciferase mRNA were diluted to 4.8 ×1010 gc mL−1 with PBS. Mice serum, human commercial intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG, HUALAN BIOLOGICAL ENGINEERING CHONGQING CO., LTD, S20113011) or human serum (Lablead, 9193 and Medbio, MEM23781) was diluted in a suitable range (from 1:10 to 1:3160) with heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum and incubated with VLP at 37 °C for 1 h and added to the BHK-21 cells in triplicate, respectively. After 24 h, transduction efficiency was tested by assessing luciferase activity described as before. The percentage of inhibition was estimated relative to positive, no-serum control samples.