Introduction

Synthetic genetic circuits facilitate the reprogramming of cells to perform myriad functions, which has enabled developments and applications that span biotechnology, chemical biology, and the like. Biological computing and large-scale genetic circuit engineering that enable said developments leverage the implementation of multi-input promoter architectures1,2,3,4, modular modeling approaches5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13, and qualitative genetic circuit design automation14,15,16,17. The successful design of genetic circuits is typically achieved intuitively via labor-intensive (experimental trial and error) optimizations to achieve a desired performance or setpoint. As the size and complexity of synthetic genetic circuits continue to increase, the design-by-eye approach is becoming untenable, given that the goal is to engineer efficient genetic circuits that minimize the resource burden on a given chassis cell or cell-free system. One of the major technical challenges of the field is that biological circuit components—i.e., genetic elements at the DNA level—are not strictly composable18,19. Qualitatively, we have a clear understanding of how to design fundamental genetic circuit architectures; however, there has been limited success regarding the quantitative prediction of genetic circuit performance20. We define this discrepancy between qualitative design and quantitative performance prediction as the synthetic biology problem (Supplementary Note 1).

Qualitatively, the control of transcriptional networks has proven to be a reliable strategy for genetic circuit design in myriad chassis cells1,4,15,21,22,23. Robust transcriptional control can be achieved using transcription factors (TFs)4,15 and CRISPR–Cas-based approaches24,25. Most iterations of circuit design utilize inversion to achieve the equivalent of a NOT (and related NOR) Boolean operation and have successfully been used in automated circuit design15,26 (Supplementary Note 2). In contrast, Transcriptional Programming (T-Pro) leverages synthetic TFs and synthetic promoters for circuit engineering3,4,27. T-Pro utilizes engineered repressor4 and anti-repressor3,28 TFs that support coordinated binding to cognate synthetic promoters—mitigating the need for inversion (Supplementary Fig. 1, Supplementary Note 2). Specifically, synthetic anti-repressors facilitate objective NOT/NOR Boolean operations that utilize fewer promoters relative to inversion-based circuits3,27. The reduction in the number of promoters and regulators is referred to as circuit compression and is an important feature of T-Pro4,27,29. We recently demonstrated that circuit compression via T-Pro can scale to all 2-input Boolean logical operations (i.e., four-state: 00, 10, 01, and 11—also see Supplementary Fig. 1) corresponding to 16 non-synonymous truth tables27. Accordingly, T-Pro circuit design allows for the qualitative engineering of cellular programs with significantly reduced complexity and less metabolic burden compared to the state-of-the-art15.

In this work we: (i) expand T-Pro wetware programming capacity from 2-input Boolean logic to 3-input (i.e., eight-state: 000, 001, 010, 011, 100, 101, 110, and 111—also see Supplementary Fig. 1) Boolean logic, (ii) develop an algorithmic enumeration method that guarantees the smallest circuit design (compression) for a given operation or truth table, and (iii) develop workflows to design any higher-state T-Pro circuit with prescriptive (predictable) quantitative performance. To accomplish this, we first engineer a set of synthetic T-Pro anti-repressors that are responsive to cellobiose. CelR anti-repressors enable the design of 3-input Transcriptional Programs upon pairing with synthetic TFs that are responsive to orthogonal signals IPTG and D-ribose3,4,28. Axiomatically, increasing Boolean logic from 2-inputs to 3-inputs permits an expansion from 16 to 256 distinct truth tables. To reconcile the truth table and the cognate circuit compression design, we develop an algorithmic enumeration-optimization software. Next, we develop workflows for the predictive design of T-Pro circuits that account for genetic context in quantifying expression levels. Using these workflows, we design numerous genetic circuits with high-level accuracy in terms of quantitative performance. In addition, we apply our workflow to (i) target specific recombinase activities for the predictive design of synthetic memory30,31, and (ii) address metabolic engineering and operon design to predictively control flux through a toxic biosynthetic pathway. Our results highlight how our wetware-software suite can be used as a generalizable technology for accurately predicting the expression of diverse proteins ranging from synthetic transcription factors that form genetic circuits for biocomputing to enzyme systems that facilitate bio-catalysis.

Results

Expanding T-Pro biocomputing wetware via a complete set of engineered cellobiose-responsive synthetic transcription factors

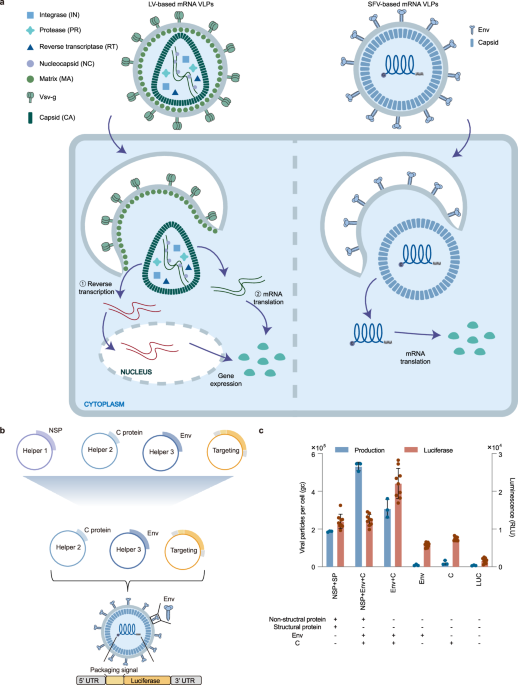

2-Input T-Pro biocomputing requires two signal-orthogonal high-performing repressor/anti-repressor sets to achieve all 16 Boolean operations, which we demonstrated in Huang et al.27 (also see Supplementary Note 3). In said study, we developed a complete set of compressed 2-input Boolean logical operations predicated on orthogonal signals IPTG and D-ribose. To expand T-Pro to a complete set of 3-input Boolean logical operations (Supplementary Fig. 1) required the development of an additional set of synthetic repressors and anti-repressors that are responsive to an orthogonal signal. Accordingly, we sought to develop an additional repressor/anti-repressor set based on the CelR scaffold, which is responsive to the ligand cellobiose and has been shown to be orthogonal to IPTG and D-ribose. We previously demonstrated that the CelR regulatory core domain (RCD) was compatible with our established synthetic promoter (SP) set—facilitated via synthetic alternate DNA recognition (ADR)4. Here, we first verified that five of said synthetic TFs could regulate a new set of T-Pro synthetic promoters based on a tandem operator design27 (Fig. 1a, b). From this set, we selected the E+TAN repressor based on gene regulation performance to initiate the design of the corresponding anti-repressors. Note, we used two metrics for E+ADR selection: (i) dynamic range, and (ii) level of the ON-state in the presence of the ligand cellobiose.

a The components of a T-Pro transcription factor are shown (left) along with an example (right). b The dynamic range is shown for the cellobiose repressor (CelR) equipped with five unique DNA-binding domains regulating a green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter gene. Each box color corresponds to the legend below. c The workflow for engineering an anti-repressor is shown. The original E+TAN regulatory performance is shown (left) along with the super-repressor (middle) and EA(1)TAN anti-repressor (right). d The regulatory performances of three EAADR transcription factor (TF) sets are shown. The dynamic range for each variant is shown on a white-blue scale for repressors, and a white–purple scale for anti-repressors. The dynamic range is defined as the high output state divided by the low output state. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Data represent the average of n = 6 biological replicates, with groups of three taken on two separate days. Error bars correspond to the SEM of these measurements.

Next, we engineered anti-CelR from the E+TAN scaffold (Fig. 1c). To accomplish this, we leveraged our established engineering workflow3,32, which involves (i) the generation of a variant that retains the DNA binding function but is insensitive to the input ligand (this phenotype is termed a super-repressor and designated as ESTAN), and (ii) one or more subsequent round(s) of error-prone PCR (EP-PCR) on the putative super-repressor ESTAN at a low mutational rate. To generate the ESTAN super-repressor variant, we performed site saturation mutagenesis at amino acid (AA) position 75, predicated on the strategy we developed in Groseclose et al.3. Mutant L75H displayed the desired phenotype (Fig. 1c), and we proceeded to use this super-repressor ESTAN as the template for EP-PCR. We then screened the resulting library (~108 variants) using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) and identified three unique anti-repressors—EA1TAN, EA2TAN, and EA3TAN (Fig. 1c, d). In turn, we equipped each of the anti-CelRs with four additional ADR functions beyond EATAN—i.e., EAYQR, EANAR, EAHQN, and EAKSL (see Fig. 1d, Supplementary Data 1, and Supplementary Data 2). Each iteration of alternate DNA binding with a given anti-CelR core retained the anti-repressor phenotype, with the best performing set represented by EA1ADR, where ADR = TAN, YQR, NAR, HQN, or KSL (Fig. 1d). With this result, we now have 3 orthogonal sets of synthetic transcription factors (wetware) to facilitate 3-input Boolean biocomputing via T-Pro.

Algorithmic enumeration of 3-input T-Pro circuits and compression optimization: T-Pro circuit qualitative design software

Scaling from 2-input (16 Boolean operations) to 3-input (256 Boolean operations) biocomputing eliminates the possibility of designing a compressed circuit intuitively (i.e., by eye). The combinatorial space for qualitative circuit construction based on 3-input T-Pro components is on the order of 1014 (see Fig. 2 and Supplementary Note 4). The challenge is to select 256 non-synonymous operations with prescribed truth tables from a search space composed of >100 trillion putative circuits, such that each solution is compressed—i.e., composed of the fewest number of parts (e.g., promoters, genes, RBS, TFs). Moreover, within the prescribed search space, many truth tables will have more than one solution. This requires an optimization strategy that will guarantee the identification of the compressed iteration of a T-Pro circuit for a cognate truth table. To accomplish this, we developed a generalizable algorithmic enumeration method for 3-input T-Pro circuits. The algorithm models a circuit as a directed acyclic graph and systematically enumerates circuits in sequential order of increasing complexity, where complexity corresponds to the degree of compression achieved by the circuit. This sequential enumeration ensures the identification of the most compressed circuit associated with a given truth table—see Methods, also see workflow given in Supplementary Figs. 2–4.

a The putative transcriptional programming design space for repressor/anti-repressor pairs is shown. RCD stands for Regulatory Core Domain, and ADR is Alternate DNA Recognition. b The codification of T-Pro is shown with an example of a repressor and an anti-repressor. c A superstructure is shown to represent all possible transcriptional programs that can be constructed with the transcription factor (TF) set used in this study. Note, superscript A indicates the anti-repressor phenotype, and the baseline “A” represents a generalized TF or the ligand cognate to the biosensor. d Representation of a single node is shown. e Representation of a dual-regulated single node is shown. f Representation of two interacting nodes is shown. g The algorithm enumerates all possible 3-input circuit configurations, based on a user-defined truth table. It then optimizes for circuit compression by selecting the smallest circuit topology that fulfills the desired logic. After identifying the optimal topology, the program assigns genetic components to maximize the circuit’s performance, ensuring minimal resource use while maintaining the desired functionality. h Examples of compressed genetic circuits generated from different truth tables are shown. The compressed code notation and corresponding circuit diagrams show the minimal design required to fulfill the given input/output logic operations. Compression ratio reported as generalized Cello circuits:T-Pro circuits. Detailed analysis and source data are provided as a Source Data file. Source code is available at: https://github.com/Jayaos/TPro.

First, we generalized the description of the synthetic transcription factors and cognate synthetic promoters to allow for >5 orthogonal protein DNA interactions, as the exact number of unique protein DNA interactions for a given circuit cannot be known a priori (Fig. 2a–c). In principle, we can scale the ADR per transcription factor to the order of ~103, noting that 2-input T-Pro only required three ADR to program all 16 logical operations27—in other words, our T-Pro wetware (synthetic promoters) can be expanded if necessary. In addition, we included T-Pro inverters that can be generated via the super-repressor phenotype (XSADR). T-Pro inverters facilitate feedforward operations (cascades, opposed to loops33) without a signal-coupled response, which may be needed for certain multi-layer circuit designs (Supplementary Note 4). Next, to reduce the initial search space, we implemented a set of rules to mitigate unnecessary conflicts in the circuit design space (Supplementary Note 4). Finally, we codified circuit descriptions to facilitate in silico enumeration (see Fig. 2b–f). Once the enumerated space is composed, we can identify all genetic circuits that correspond to a given truth table. In turn, from the set of circuits that match a given truth table we can select the most compressed iteration from the enumerated subset (Fig. 2g). Using our T-Pro enumeration workflow (Supplementary Figs. 2–4) we were able to identify all 256 putative low-resolution circuits optimized for compression (Supplementary Data 3). Notably, on average, our resulting multi-input compressed T-Pro circuits were approximately 4 times smaller than canonical inverter-based genetic circuits, examples given in Fig. 2h. Next, we developed a second workflow to quantitatively predict the detailed high-resolution composition for circuit performance—described in the sections that follow (also see Supplementary Figs. 5–17).

Genetic context impacts circuit performance—introducing the context-specific expression cassette (CSEC)

Qualitatively, we have a clear understanding of the design rules for a basic genetic circuit. However, given a promoter of strength x and an RBS of strength y, we cannot quantitatively predict the expression level of a gene of interest (GOI) with a given reading frame z a priori. We define the discrepancy between qualitative design and the prediction of a genetic circuit with a prescribed quantitative performance as the synthetic biology problem (Supplementary Note 1, Fig. 3a). The aforesaid can be regarded as a grand challenge in synthetic biology and is currently an active research problem8,34,35,36,37,38,39. To address the synthetic biology problem in the context of T-Pro circuit design, we systematically evaluated the parts of a genetic circuit—i.e., promoter, genetic insulator, RBS, and reading frame—in the context of synthetic (T-Pro) transcription factor expression levels. We posited that reconciling the context elements that map genotype to synthetic transcription factor expression levels would enable the predictive design of single-input single-output (SISO) operations with prescribed quantitative performances—i.e., the design of BUFFER and NOT logic gates with desired setpoints for dynamic range. Moreover, we postulated that the prediction of quantitative SISO performance would facilitate the prediction of all multiple-input single-output (MISO) operations for 3-input logic with prescribed setpoints.

a An illustration of the synthetic biology problem is shown. b Expression levels are shown for constructs where 0–25 amino acids of the lactose repressor (LacI) were fused to the N-terminus of green fluorescent protein (GFP) and expressed from the O1 promoter. Note, GOI stands for gene-of-interest. c Expression of GFP versus 25ADR–GFP fusion reporters from five synthetic promoters is shown in terms of expression units (EU; see Methods for definition). Note, ADR stands for alternate DNA recognition. d Expression of 25ADR–GFP versus 25ADR-mKate (red fluorescent protein, data distinguished via an asterisk symbol* and blue frame) from five synthetic promoters is shown. e A ribosome binding-site (RBS) library applied to two promoters does not show modularity. f An illustration of the context-specific expression cassette (CSEC) is shown. g The expression levels of five different promoter-RBS libraries are shown. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Data represent the average of n = 6 biological replicates, with groups of three taken on two separate days. Error bars correspond to the SEM of these measurements.

Given the large number of variables defining gene context, our first objective was to develop an accurate proxy for synthetic transcription factor (T-Pro) expression that can be quantitatively observed. A common strategy for evaluating the strength of a defined promoter and RBS is via the expression of a reporter—e.g., green or red fluorescent proteins (GFP or RFP). However, this approach does not necessarily capture the performance of the promoter and RBS in the context of the GOI. In this study, our GOIs are T-Pro synthetic TFs; accordingly, our goal was to develop an accurate reporter system (observable) for expression levels of said proteins. To accomplish this, we created a synthetic ADR fusion protein with GFP (ADR-GFP), see Fig. 3b. The justification for this approach was the need for an accurate general reporter for all synthetic T-Pro TFs used in this study. Accordingly, we characterized the fluorescence of fusion reporters composed of the low-variable region of the ADR primary structure represented in all T-Pro transcription factors—i.e., ranging from 1 to 25 AA, Fig. 3b, also see Supplementary Note 5—to determine the point of stabilized expression. Protein expression varied significantly in the range of 16-25 amino acids, in which a stable pattern of expression was achieved. Accordingly, to capture the representation of ADR across all synthetic transcription factors used in this study, we selected the fusion of 25 AA as the final reporter system—designated as 25ADR-GFP herein.

To test our assertion, we measured the constitutive expression of (i) our 25ADR-GFP chimeric reporter relative to (ii) an unmodified GFP reporter gene measured via Expression Units (EU)—see Methods for definition. Expression patterns for each reporter were measured under the control of different T-Pro synthetic promoters designed for this study (Fig. 3c). Consistent with our supposition, we observed different expression patterns between the 25ADR-GFP reporter and an unmodified GFP reporter using different synthetic promoters. However, when we compared a 25ADR-GFP to a 25ADR-RFP reporter under the control of the same set of synthetic promoters, we observed a clear agreement in expression levels (Fig. 3d). This observation enabled us to identify the GOI leader sequence as our first design heuristic for the context elements required for predictable gene expression.

Next, we determined the extent to which a given RBS was impacted by the context of defined synthetic promoters with a fixed GOI leader sequence (e.g., 25ADR–GFP). Noting that RBS calculators have been developed to predict translation rates a priori40,41—implying that the RBS element is modular—we posited that the genetic context proximal to the RBS can impact the element’s performance. This is predicated on anecdotal evidence based on the said calculators’ inability to systematically predict relative changes in gene expression in many of our circuit designs. To determine if a given RBS is context-dependent, we constructed an RBS library composed of 11 different sequences and evaluated the performance of each RBS using two different synthetic promoters expressing the same 25ADR–GFP reporter (Fig. 3e, Supplementary Data 1, Supplementary Data 2). The relative RBS calculated strengths were not conserved between the two synthetic promoters. Moreover, a broader assessment using three additional synthetic promoters revealed a similar outcome—confirming that RBS strength is indeed context dependent (see Supplementary Fig. 18). Finally, we demonstrated that different ribozyme (insulator) sequences also affect protein expression levels—specifically in the context of identical promoter and RBS sequences (Supplementary Fig. 19). From this set of observations, we concluded that to fully reconcile quantitative protein expression requires four context elements: (i) promoter identity, (ii) insulator (ribozyme) identity, (iii) RBS identity, and (iv) the GOI leader sequence—collectively termed a Context-Specific Expression Cassette (CSEC) (see Fig. 3f, Supplementary Note 1). Using these data, we constructed a lookup table for CSEC elements that correspond to combinatorial synthetic (T-Pro) promoters mapped to various setpoint expression levels of a 25ADR–GFP reporter (Fig. 3g). We posited that the resulting CSEC lookup table can be used for the predictive design of T-Pro SISO circuits.

Predictive setpoint design of fundamental single-input single-output (SISO) transcriptional programs

Next, we developed a workflow to quantitatively design fundamental SISO T-Pro circuits. SISO T-Pro circuits require precise control over the expression levels of cognate synthetic TFs from a constitutive promoter. Namely, the under-expression or over-expression of a given synthetic TF can have a negative impact on the dynamic range of the circuit (see Supplementary Figs. 5–17, T-Pro Quantitative Design). In addition, identifying the expression optima concurrently minimizes metabolic burden in that the circuit is not producing more TF than necessary. In Fig. 4a, we describe our initial design goal, which is to generate an E+TAN BUFFER circuit that maximizes the difference between the ON-state and the OFF-state (i.e., Δmax) for a given (pre-designed) T-Pro synthetic promoter. Here, the pre-designed synthetic (regulated) promoter is designated as context element CSECOUT selected from the lookup table given in Fig. 3g. The CSECOUT defines the upper limit of the circuit’s performance in the ON-state—in this case, no more than 2627 expression units (EU).

a A representative single-input single-output circuit is shown as the design goal to optimize. b The genetic schematic for the transcription factor titration circuit is shown (left) along with the expression units (EU; see Methods for definition) standard curve for the pLuxm promoter (right). c An example dataset generated from the measurement of E+TAN in the circuit from b is shown (left). The performance metric is shown to the right. EUin corresponds to the EU value at which the transcription factor (TF) is expressed, and EUout corresponds to the measured fluorescence of the 25ADR–GFP reporter, where ADR is alternate DNA recognition and GFP is green fluorescent protein. d The genetic context of a ribosome binding-site (RBS) library designed for modulating the constitutive expression of TFs is shown (inset) with corresponding data. CSEC stands for context-specific expression cassette. e The genetic schematic of an optimized BUFFER circuit is shown (left) along with the predicted and experimental data (right). f The predicted and experimental comparisons are shown for five E+ADR BUFFER circuits. g The genetic schematic of an optimized NOT circuit is shown (left) along with the predicted and experimental data (right). h The predicted and experimental comparisons are shown for five EAADR BUFFER circuits. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Data represent the average of n = 6 biological replicates, with groups of three taken on two separate days. Error bars correspond to the SEM of these measurements.

Next, we developed a titration circuit that used the pLuxm promoter to vary the expression level of the T-Pro synthetic TF E+TAN, which in turn regulates a cognate synthetic promoter (CSECOUT)—collectively defining the BUFFER gate (Fig. 4b). The purpose of the titration circuit is to rapidly vary the strength of the promoter producing E+TAN without circuit rebuilding, intended to accelerate and facilitate quantitative design. The titration circuit was characterized with and without the cognate inducer of the T-Pro synthetic transcription factor and describes the performance of the circuit at different concentrations of the biosensor E+TAN (Fig. 4c). Note, the input is digitized such that 0 corresponds to no cellobiose, and 1 corresponds to saturating concentrations of the input (i.e., + cellobiose).

In turn, we identified the BUFFER Δmax using a numerical optimization (Supplementary Figs. 14 and 15, T-Pro Quantitative Design) that correlates the EU value for the concentration of the biosensor E+TAN to a putative EUOUT performance Δmax value—in this case, ~110 EUs. Finally, we identified the appropriate promoter-RBS combination from our extant library of tested context elements to achieve this EU value (Fig. 4d). The resulting circuit was faithful to the design goal, and accurate within 1.4-fold of the predicted value (Fig. 4e). The tested circuit had a slightly better Δmax performance than the predicted value due to the OFF state being lower than expected (a desirable result for minimizing unintended OUTPUT expression). In turn, we applied this workflow to the design of four additional E+ BUFFER circuits with different DNA-binding functions (Fig. 4f). Each BUFFER operation required a separate titration circuit to facilitate the identification of Δmax for a given synthetic promoter corresponding to CSECOUT (Supplementary Fig. 20). All EUIN RBSs were selected from the lookup table given in Fig. 4d. In general, we observed good agreement between the predicted Δmax and the measured Δmax values. In addition, we applied a similar workflow toward the design of EA anti-repressors with similar agreement between the predicted and measured dynamic ranges (Fig. 4g, h, and Supplementary Fig. 20).

To further validate our predictive workflow, we built and tested all remaining 20 fundamental T-Pro BUFFER and NOT gates corresponding to I+/A and R+/A (Supplementary Figs. 21–24). The data showed highly accurate predictions from the model relative to the measured values, with an average error of <1.4-fold—often with Δmax values significantly better than predicted values, analysis given in Supplementary Fig. 25. In addition, we validated orthogonality to cognate synthetic promoters, a prerequisite for MISO circuit design (Supplementary Fig. 26). This collection of results confirmed that our CSEC workflow can be used for the quantitative prediction of expression levels for fundamental (SISO) T-Pro circuits.

Predictive setpoint design of multiple-input single-output (MISO) transcriptional programs

Building on our ability to accurately design SISO Transcriptional Programs, we developed a complementary workflow (Supplementary Figs. 5–13) for the predictive design of multiple-input single-output (MISO) T-Pro circuits—leveraging the models we developed in Milner et al.8 (see models and software given in Supplementary Figs. 14–17). Here we illustrated said workflow for the design of an A IMPLY B circuit (Fig. 5). Namely, we posited that complex MISO circuit prediction can be derived from SISO predictions. First, we generated a truth table mapping inducer input states to output gene expression states (Fig. 5a). Next, we used our enumeration algorithm to generate the compressed circuit topology for said logical operation (Fig. 5b). In turn, we generated a granular circuit description based on extant parts (elements), which defined the boundary for the circuit design (Fig. 5c). Once the design boundary was set, we concurrently optimized SISO EUIN and SISO EUOUT(1). Given the optimized values for the expression units corresponding to EUIN and EUOUT(1), we identified the context-specific RBS for each layer of the circuit (Fig. 5d). Finally, we built and tested said circuit and compared the predicted values to the measured values. Our result demonstrated a near-perfect correlation between the predicted performance and the measured performance (Fig. 5d). Moreover, we designed 10 additional nontrivial 2-input programs—i.e., AND, NOR, NIMPLY, NAND, OR, IMPLY, XOR, and XNOR—with a similar degree of success (Supplementary Fig. 27). This collection of results supports our general supposition that predicted SISO performance can be leveraged to predictively design compressed 2-input T-Pro circuits.

a A representative multiple-input single-output circuit is shown as the design goal to optimize. b A generic genetic schematic for the compressed circuit in a is shown—i.e., 5 to 2 (5:2) inducible promoters generalized Cello design relative to T-Pro. c The variables open to optimization are shown for the circuit in question (left), along with the transcription factor (TF) titration curves for the two chosen regulators (right). Both x- and y-axis are in Expression Units (EU; see Methods for definition). d The final optimized genetic architecture is shown (left) along with the comparison of the predicted and experimental data (right). e The genetic schematic for an optimized 3-input XNOR (consensus) circuit is shown (top) along with a truth table representation (bottom left) and a comparison of the predicted and experimental data (bottom right). Compression ratio reported as generalized Cello circuits:T-Pro circuits. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Data represent the average of n = 6 biological replicates, with groups of three taken on two separate days. Error bars correspond to the SEM of these measurements.

Next, we demonstrated that our workflow can be applied to 3-input circuit design. In this example, we selected the 3-input XNOR operation (or Consensus gate) as our design goal. We selected this logical operation for benchmarking, given that this genetic circuit was the most complex Cello design reported by Nielsen et al.15. Using our workflow, the resulting program required the concurrent optimization of multiple SISO sets. The design of this program using T-Pro only required 6 TFs and 4 regulated promoters, while the Cello design required 10 TFs and 13 regulated promoters via the use of tandem promoters, and 18 promoters when generalized—i.e., resulting in an 18 to 4 compression (Fig. 5e). After constructing and testing this program, no state was greater than ~1.5-fold off from the prediction, which is more accurate than the Cello design where most states were >10-fold off from the prediction. In general, our quantitative predictions had an average error below 1.4-fold validated via >50 test cases, as given in Supplementary Fig. 25. A summary of the qualitative and quantitative workflows for circuit engineering is given in Supplementary Figs. 2–17.

Additional context variables and relative circuit performance

In addition to genetic contexts, we posited that chassis cell type and nutrient conditions will also have an impact on circuit performance (Supplementary Note 1). To test this assertion, we evaluated two BUFFER gate circuits in nutrient rich media and in BL21 Escherichia coli (E. coli) cells, relative to the reference system—i.e., 3.32 E. coli chassis cells in minimal media—see Fig. 6a–f. In other words, the genetic context (promoter, RBS, GOI, plasmid) remained constant while the environment was changed. Qualitatively, the BUFFER operations performed as expected in all environments; however, quantitatively, there were moderate differences in circuit performance upon a change in chassis cell and nutrient conditions. Given the performance of the two SISOs, we were able to accurately predict the quantitative performance of the cognate MISO (i.e., BUFFERs to AND gate), substantiating our engineering workflow and central claim regarding improved circuit composability upon reconciliation of context variables (Fig. 6g–i and Supplementary Figs. 14–17).

a–c A representative single-input BUFFER gate responding to cellobiose is shown in four distinct contexts defined by host strain (E. coli 3.32 or BL21) and growth media (minimal medium or LB). Logic operation (a), genetic circuit schematic (b), and corresponding reporter expression levels in Expression Units (EU; see Methods for definition) (c) are shown. d–f A second single-input BUFFER gate responding to ribose is similarly characterized across contexts with the logic operation (d), genetic circuit schematic (e), and experimental data (f) shown. g–i A two-input AND gate responsive to cellobiose and ribose shows that quantitative performance varies across chassis and media. Logic operation (g), genetic circuit schematic (h), and predicted vs. measured outputs (i) highlight that accurate prediction is possible after context re-characterization. j Ribosome binding-site (RBS) scaling factors measured using constitutive expression of 25ADR-GFP fusion protein under the Pttg promoter across different contexts reveal differing expression levels, necessitating re-characterization. LacI stands for the lactose repressor, and GFP is green fluorescent protein. k–l Compressed T-Pro logic gates outperform inversion-based designs in NOT (k) and NOR (l) configurations, with improved dynamic performance. Circuit schematics (left) and time-course outputs (right) are shown. Ligand(s) were added 180 min after cells were passaged into fresh media. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Data represent the mean of n = 3 biological replicates, each measured on a separate day. Error bars indicate the standard error of the mean (SEM).

To further investigate the origin of how variation in growth media and chassis cell type impact circuit performance we reevaluated RBS strength under different environmental contexts (Fig. 6j and Supplementary Fig. 28). In brief, in all cases variation in chassis cell and growth media impacted RBS performance. This observation implies that RBS lookup table recalibration in the context of the selected chassis cell and growth media will be necessary to facilitate quantitative predictions; otherwise, our workflows and cognate models remain intact.

Finally, we conducted a direct comparison between inverter-based circuits and T-Pro analogs (Fig. 6k, l). Here, we engineered NOT and NOR gates as inverter-based circuits, and as compressed (T-Pro) iterations. The justification being that NOT/NOR Boolean operations can be used to construct any program in vivo15,42 or in silico43. Accordingly, an assessment of said operations can serve as a reasonable proxy for more complex operations. Moreover, we constructed both iterations (inverter and non-inverter circuits) using T-Pro parts. In general, both compressed (T-Pro) NOT and NOR operations displayed significantly faster response times upon induction (Fig. 6k, l and Supplementary Fig. 29).

Leveraging the CSEC workflow for the design of prescribed enzyme activity in situ

Next, we posited that we could engineer a reporter proxy—analogous to 25ADR-GFP—to facilitate the in situ quantification of enzyme function at low expression levels. To test our supposition, we defined the correlation between the A118 integrase protein expression and activity. Namely, we used the more sensitive Nanoluc fusion reporter to generate an EU standard curve for A118 (Supplementary Figs. 30 and 31, also see Fig. 7a, b) and concurrently constructed a recombination circuit to measure A118 activity. Here, the full A118 gene was expressed from the pLuxm promoter, and a constitutive, inverted promoter flanked by A118 att sites upstream of a gfp gene was included to measure A118 recombination in the context of GoF memory (Fig. 7c). By correlating the two results and fitting them to a non-linear curve, we were able to visualize the functional performance of A118 at various expression levels (Fig. 7a–d). We validated the accuracy of this correlation by tracing back the 516,500 EU measured with the BAC A118-Nanoluc to its recombination efficiency of 96.6% (Fig. 7d). This value closely aligned with the 98% efficiency measured through experimental validation. We further confirmed that our Nanoluc EU measurements can be applied accurately to control integrase activity by constructing a T-Pro-controlled recombination circuit specifically targeting a 70% recombination efficiency through EU-guided RBS tuning (Fig. 7e–h).

a The genetic schematic of a Nanoluc luciferase context-specific expression cassette (CSEC) is shown. b The nanoluc expression units (EU; see Methods for definition) for the uninduced and induced states of (a) are shown. c The genetic schematic for an inversion-based recombination circuit is shown. d The recombination percentage as a function of A118 recombinase expression is shown. e The genetic schematic for E+TAN regulating A118-Nanoluc to achieve a targeted expression level is shown. f The uninduced and induced expression levels for the circuit in (e) are shown. g The genetic schematic for E+TAN regulating A118 and an inversion gain-of-function (GOF) circuit are shown. h The predicted and experimental recombination percentages are shown for the circuit in (g). Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Data represent the average of n = 6 biological replicates, with groups of three taken on two separate days. Error bars correspond to the SEM of these measurements.

Using genetic context to engineer prescribed metabolic flux

We posited that the workflows we developed in this study could be applied (extrapolated) to the rational design of flux through a heterologous metabolic pathway involving our synthetic T-pro transcription factors for lycopene production in E. coli. The production of lycopene in E. coli is typically achieved by expressing three heterologous genes (crtE, crtB, and crtI)44 (Fig. 8a), which are often organized into an operon45,46,47 (see Supplementary Note 6). Noting reports regarding challenges with toxicity when expressing this pathway48,49,50,51, we reasoned that we could use our titration workflow to characterize the production of each gene and then rationally engineer the expression levels using fusion reporters—i.e., at levels that would mitigate toxicity. To achieve this, we placed each gene under the control of a different T-Pro regulator and determined the dose-response functions for each expression cassette using GFP fusion reporters for each enzyme represented in the metabolic pathway—i.e., (i) 25CrtE-GFP, regulated by BUFFER R+YQR, (ii) 25CrtB-GFP, regulated by BUFFER E+TAN, (iii) 25CrtI-GFP, regulated by I+NAR (see Fig. 8b, c). We then assembled a refactored circuit to express the full-length genes (Fig. 8d). We chose to express each crt gene at a low EU value of ~102 by providing the appropriate inducer concentrations—i.e., 100 μM D-Ribose, 570 μM cellobiose, and 10 μM IPTG. This allowed us to achieve a lycopene titer of 341 ng/ml in batch culture and mitigated our issues with genetic instability of the circuit (Fig. 8e).

a The biosynthetic pathway for lycopene production is shown. b The genetic schematic for measuring expression units (EU; see Methods for definition) of each Crt gene is shown. c The dose-response functions of the three circuits from (b) are shown in EU. The vertical dashed lines indicate the inducer concentration that yields an EU of 100. d The genetic schematic for the fully refactored synthase pathway is shown. e The measured lycopene titer from the circuit in (d) is shown. f The genetic schematic for measuring EU of the Crt genes in an operon is shown. g The measured EU values for the three constructs from (f) are shown. h The genetic schematic for the functional operon is shown. i The measured lycopene titer from the circuit in (h) is shown. G3P glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate, DXP 1-deoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphate, HMBPP 1-hydroxy-2-methyl-2-(E)-butenyl 4-diphosphate, IPP isopentenyl pyrophosphate, DMAPP dimethylallyl pyrophosphate, FPP farnesyl pyrophosphate, GGPP geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate, Dxs DXP synthase, Idi isopentenyl-diphosphate isomerase, CrtE GGPP synthase, CrtB phytoene synthase, CrtI phytoene desaturase. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Data represent the average of n = 6 biological replicates, with groups of three taken on two separate days. Error bars correspond to the SEM of these measurements.

In turn, we designed three GFP fusion constructs to quantify the context-specific expression of each gene in an operon milieu, with the goal of matching the ~102 (i.e., 50–100) EU level used above for each gene (Fig. 8f). Each GFP fusion was designed to retain all DNA upstream of the GOI, including the first 25 AA of the GOI as before. At the outset, we generated libraries for each of the three RBSs and screened them for variants with an EU of ~50–100. Our final expression levels were close to the target, with EUs of 100, 100, and 50 for CrtE, CrtB, and CrtI, respectively (Fig. 8g). We then assembled a functional operon under the control of R+YQR (induced to the maximum output level via a saturating amount of ligand) and measured the lycopene titer to be 365 ng/ml, which was comparable to the titer achieved with the titrated system expressed at the same levels (Fig. 8h, i).

Discussion

While this study illustrates the advance of T-Pro from four-state programming (2-input Boolean logic) to eight-state programming (3-input Boolean logic), a key question is whether the wetware, software, and workflows can be extended to even higher states of synthetic decision-making. We can expand our wetware to support >3-input Boolean logic—as we have projected our design space to be on the order of 106 biosensors and 103 synthetic promoters52. Moreover, we posit that the workflow and models will continue to be effective given that circuit composition is predicated on SISO to MISO construction—barring metabolic limits of the chassis cell. However, our current approach to algorithmic enumeration of 3-input T-Pro circuits and compression optimization is computationally expensive, and it will be challenging to scale this approach to 16-states or greater, as this would require advancing from 256 operations to > 65,000 operations. To address this challenge, we are actively exploring strategies that balance biological feasibility and computational tractability (Supplementary Note 7).

In contrast to this study, there have been significant efforts to develop sequence-based models for the design and control of transcription53,54,55,56 and translation40,41, but they have not progressed to the point where their accuracy surpasses experimental characterization of unique constructs (i.e., library screening). To illustrate this, we used the most recent versions of the RBS40 and Promoter Calculators56 to predict the expression level of 77 constructs tested in this study (Supplementary Fig. 32). The data correlated poorly with the model prediction, indicating that our workflow for evaluating protein expression with relevant context elements represents an advance over sequence-based model predictions of gene expression.

While this study primarily focused on comparing T-Pro to traditional inverter-based circuits, other circuit frameworks can be used to generate Boolean operations such as CRISPRi-based logic gates57 or RNA-based regulators58. To glean how different iterations of circuit frameworks compare to T-Pro, we conducted a qualitative comparison of fundamental NOR logical circuits (Supplementary Fig. 33). As indicated before, NOR logic can be used to construct any higher-state logical operation and can serve as a reasonable first approximation of how effective T-Pro circuit compression compares to other genetic circuit technologies in a broader context. Consistent with our supposition, the T-Pro circuit required the fewest number of parts; this is also the case when comparing AND gate qualitative designs. While this is not a comprehensive assessment, it is unlikely that the genetic footprint of more complex gates will fare any better relative to T-Pro, given the fundamental constraints of the design rules for RNA-based and CRISPRi-based gates. Overall, we believe that our wetware-software technology represents an advance in genetic circuit design, and we posit that circuit compression will have an impact on future applications of synthetic biology in a broad range of areas59,60,61,62,63,64,65.

Methods

Bacterial strains and media

E. coli strains used were NEB® 10-beta (for cloning), chemically competent BL21 (NEB) (for assays), and 3.320 (lacZ13(Oc) lacI22 λ− el4- relA1 spoT1 thiE1; Yale CGSC #5237) (for assays). Marionette-Wild5 was used to assay expression levels from BAC constructs harboring recombinases and their CSEC variants. E. coli were routinely cultured aerobically in LB Miller medium (Fisher BP9723) at 37 °C (unless otherwise specified), in M9 minimal medium (MM) (MM contains 3 g/L KH2PO4, 0.5 g/L NaCl, 6.78 g/L Na2HPO4, 1 g/L NH4Cl, 0.1 mM CaCl2, 2 mM MgSO4, 1 mM thiamine hydrochloride, 0.4% D-glucose, and 0.2% casamino acids), or on LB Miller agar (Fisher BP1425). Antibiotics for plasmid selection were used at the following concentrations: carbenicillin (Goldbio C-103-25)- 100 μg/ml; chloramphenicol (Goldbio C-105-25)—25 μg/ml; kanamycin (Goldbio K-120-25)—35 μg/ml.

Chemical inducers

The following chemicals were used as inducers: Isopropyl-beta-D-thiogalactoside (IPTG, Goldbio I2481C); D-ribose (Alfa Aesar A17894); Cellobiose (Acros Organics 108461000); 3-Oxohexanoyl-homoserine lactone (AHL, Sigma K3007); 2,4-Diacetylphloroglucinol (DAPG, Acros Organics 15214288). Unless otherwise specified, the final concentrations used for each inducer were: 10 mM IPTG; 10 mM D-ribose; 10 mM cellobiose; 0.1 nM–10 μM AHL; 25 μM DAPG.

Cloning and plasmid construction

Plasmids were created using Golden Gate assembly66, inverse PCR followed by blunt-end ligation, or Gibson cloning67. Q5 polymerase (NEB M0491L) was used for PCR. T4 DNA ligase (NEB M0202L), BsmBI-v2 (R0739L), and BsaI-HFv2 (NEB R3733L) were used for Golden Gate cloning. NEBuilder HiFi DNA Assembly Master Mix (NEB E2621X) was used for Gibson cloning. All DNA primers were synthesized by Eurofins Genomics. The DNA sequences of all constructs were verified by Sanger sequencing or whole plasmid sequencing (Eurofins Genomics). All genetic part sequences used in this study are given in Supplementary Data 1. A complete list of plasmids used is provided in Supplementary Data 2.

Generation of a CelR super-repressor

We used site-saturation mutagenesis to create the CelR super-repressor. Primers were designed with NNK degeneracy targeting L75 of CelRTAN and used to create a library of TFs. This linear DNA library was circularized using the KLD method with an enzyme mixture composed of T4 polynucleotide kinase (NEB M0201L), T4 DNA ligase (NEB M0202L), and DpnI (NEB R0176L), and then transformed into chemically competent NEB® 10-beta cells. More than 1000 colonies were scraped and pooled for DNA extraction to generate a plasmid library. This library was transformed into chemically competent 3.320 cells harboring plasmid pHY202. 96 colonies were screened using the Fluorescence Assay (below) to find super-repressors. Candidates had their plasmid DNA isolated and sequenced.

Fluorescence assay

Cells were transformed with the plasmid(s) harboring a circuit of interest and selected on LB agar with the appropriate antibiotics for plasmid maintenance. After overnight incubation, individual colonies were used to inoculate 200 μl LB cultures (with appropriate antibiotics), which were grown in a flat-bottom 96-well plate (Corning 3370) sealed with a Breathe Easier membrane (Electron Microscopy Sciences 70536-20). After overnight growth (~16–20 h) in a Thermo Scientific MaxQ 4000 shaker at 300 rpm, cells were diluted 1:200 into fresh LB medium and grown for an additional 8 h. Cells were then diluted 1:200 into MM with the appropriate inducer(s) and grown for 12 h. After this final growth period, 100 μl of each culture was transferred to a black-walled, clear-bottom 96-well plate (Corning 3603). OD600 absorbance and GFP fluorescence (485/510 nm excitation/emission) were then measured using an M2e Spectramax spectrophotometer.

Expression unit (EU) metric

We define expression units (EU) as a relative measure of gene expression that captures both transcriptional and translational output. In contrast to relative promoter units (RPUs)35, which quantify promoter activity by normalizing fluorescence output to a reference promoter under standardized conditions, EU incorporates the local sequence context downstream of the promoter—specifically the 5′ untranslated region (5′ UTR) and the coding sequence in proximity to the start codon. This region is critical for translation initiation efficiency, making EU more representative of the overall protein expression potential of a gene. Supplementary Note 5 elaborates on the assumptions and rationale underlying the use of the EU metric in our study.

Error-prone PCR library construction

Error-prone PCR was performed on CelRTAN containing the L75H mutation using the following formula: 5 μL Mg-free Taq buffer (NEB B9015S), 4 μL of 1 mM dATP (NEB N0446S), 4 μL of 1 mM dGTP (NEB N0446S), 4 μL of 5 mM dTTP (NEB N0446S), 4 μL of 5 mM dCTP (NEB N0446S), 3.6 μL of 25 mM MgCl2 (NEB B9021S), 4 μL of 2.5 mM MnCl2 (Millipore Sigma M1787), 2.5 μL each of 10 μM forward and reverse primer (Eurofins Genomics), 20 ng of template DNA, and 14.4 μL of DI-H2O. Six PCR reactions were performed, with three reactions using 20 cycles and the other three using 25 cycles. Separately, a destination vector (pHY003) was constructed containing BsmBI restriction sites. Following EP-PCR, the reactions were gel extracted from 0.8% agarose gels and purified with the Zymoclean Gel DNA Recovery Kit (D4007). Libraries were Golden Gate assembled using 1 μl of an equal volume mix of BsmBI and T4 DNA ligase with 450 ng insert and 350 ng vector in 50 μl reactions (65 cycles of 42 °C/16 °C (5 min/5 min) followed by 20 min at 55 °C and then 20 min at 80 °C. 50 ng of library was transformed into 50 μl electrocompetent NEB® 10-beta cells for a total of 10 transformations. These cells were recovered in SOC medium (NEB B9020S) at 37 °C for 1 h before plating on LB agar with chloramphenicol. Following overnight growth at 30 °C, lawns were scraped into DI water, and DNA was purified by miniprep. Library DNA was then transformed into electrocompetent 3.320 cells harboring plasmid pHY202 (the reporter circuit). Fifty nanograms of DNA were transformed into 50 μl aliquots for a total of 10 transformations. These cells were recovered in SOC medium at 37 °C for 1 h before plating on LB agar with chloramphenicol and kanamycin. Following overnight growth at 30 °C, lawns were scraped into LB with chloramphenicol and kanamycin and frozen stocks were prepared with 25% glycerol to be stored at −80 °C.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)

Starting with cell stocks from the error-prone PCR library, we initially diluted them 1:100 into 5 mL of LB containing chloramphenicol and kanamycin, allowing for 8 h of growth. This was followed by a second dilution of the cultures 1:100 into M9 minimal medium with 10 mM cellobiose, with a subsequent 12-h growth period. We then centrifuged 100 μL of these cultures at 10,000g for 3 min to pellet the cells. The pellets were resuspended in a sort buffer comprising PBS, 25 mM HEPES, and 1 mM EDTA. For sorting, we mixed 500 μL of this cell suspension with 2 mL of sort buffer. Cell sorting was executed using the BD FACS Aria™ Fusion System, utilizing a 488 nm laser for excitation and 530 nm emission optics for detection. We collected 700,000 low-fluorescing cells into 1 mL of 2× concentrated LB, then added kanamycin and chloramphenicol to the final volume and incubated the cells for 24 h. After a 1:100 passage into fresh LB for another 8-h growth, the cultures were again diluted 1:100 into M9 with cellobiose and subjected to a repeat of the sorting process, collecting 300,000 low-fluorescing cells. This procedure was then repeated twice more, but without any inducer, collecting 500,000 highly fluorescent cells in the first round and 200,000 in the final round. The cells were plated on LB agar with kanamycin and chloramphenicol and incubated for 16 h. Individual colonies showing the target phenotype were selected for fluorescence assays with and without cellobiose, grown in 40 mL of LB overnight, and plasmid DNA was extracted using the Omega D6942-00S kit. Finally, sequencing analysis was conducted to identify the mutations.

Recombinase assay

Cells were co-transformed with a p15a plasmid encoding the transcription factor and a pSC101 plasmid carrying the recombinase and its corresponding Gain-of-Function (GOF) circuit. Transformants were plated on LB agar supplemented with chloramphenicol and kanamycin. Following overnight growth, three independent colonies were inoculated into 200 μl LB medium with the same antibiotics in a flat-bottom 96-well plate (Corning 3370) sealed with a Breathe Easier membrane (Electron Microscopy Sciences 70536-20). Cultures were incubated for 8 hours at 300 rpm in a Thermo Scientific MaxQ 4000 shaker before being diluted 1:200 into 200 μl M9 minimal medium, prepared with or without the corresponding recombinase inducer. After 12 h of growth under these conditions, cultures were again diluted 1:200 into fresh M9 minimal medium without any inducers and incubated for an additional 12 h. Finally, cells were diluted 1:50 into PBS containing 2 mg/ml kanamycin to halt further protein synthesis. After incubation at room temperature for ≥1 hour, samples were analyzed for recombinase activity by flow cytometry (see “Flow cytometry analysis”).

Flow cytometry analysis

Cell populations were analyzed using a Beckman Coulter Cytoflex S flow cytometer. Prior to measurement, samples were diluted 1:50 into PBS supplemented with 2 mg/ml kanamycin and incubated for a minimum of 1 h at room temperature. Data were acquired at flow rates between 10 and 30 μL/min with GFP fluorescence detected in the FITC channel. Events were filtered by forward scatter area vs. side scatter area to exclude debris, followed by side scatter height vs. side scatter area to remove doublets. For each sample, at least 10,000 single-cell events were recorded and used for subsequent analysis.

Luminescence assay

Growth conditions were the same as those in the Fluorescence Assay. After the final growth period, 100 μl of culture was then transferred to a black, clear-bottom 96-well microplate (Corning 3631) to measure OD600 using an M2e Spectramax spectrophotometer. The remaining 100 μl culture was pelleted by centrifugation (4000×g 10 min) after which the supernatant was removed. The pellet was resuspended in 20 μl of Bugbuster Mastermix (Millipore 71456) and incubated at room temperature for 30 min to facilitate cell lysis. Luminescence was assessed using the Nano-Glo Luciferase Assay Kit (Promega). Substrate and buffer were combined at a 1:50 ratio, and 10 μl of this reagent mix was dispensed into white, flat-bottom 96-well plates (Costar 3912) preloaded with 80 μl DI water. Ten microlitres of lysate (diluted 1:10 in PBS) was added to each well, mixed, and incubated for 5 min before measurement. Luminescence was read on a Spectramax M2e plate reader (Molecular Devices) with a gain setting of 800v and 30 reads per well. Data were collected with the SoftMax Pro Software. Background signal from BugBuster alone was subtracted for each data, and luminescence values were normalized to OD600.

Algorithmic enumeration of 3-input circuits

A directed acyclic graph (DAG) was constructed to systematically map general circuits to functional outputs, represented by truth tables. In this DAG, the nodes correspond to transcriptional programming cassettes, with the root node representing the cassette that regulates the output protein. Given an input sequence (i.e., a set of ligands), the circuit’s functional behavior is recursively computed through the DAG. Circuits are then enumerated in increasing order of complexity, where complexity is defined by the number of nodes in the graph, corresponding to the number of promoters in the circuit. We implemented the entire DAG structure, including nodes, transcription factors, and transcriptional programming cassettes, as distinct object-oriented components using Python. Specifically, the DAG class serves as a wrapper class representing a circuit, encapsulating nodes, transcription factors, and transcriptional programming cassettes. This design enables modular and scalable circuit enumeration while maintaining flexibility for future expansions and optimizations. The source code with implementation instructions is available at https://github.com/Jayaos/TPro.

A finite set of generalized transcription factors, comprised of a set of RCDs capable of processing 3 orthogonal inputs, at least 5 ADRs with a corresponding number of cognate synthetic promoters, and 3 phenotypes (repression, anti-repression, and super-repression), is used as components for circuit design. The enumeration begins with evaluating the functionality of all possible circuits in the simplest design space—those with one constitutive promoter in addition to the promoter regulating the output. Next, circuit complexity is increased by adding either an additional constitutive promoter or a regulated promoter, and all possible circuits within this expanded design space are enumerated. This cycle of increasing complexity followed by circuit enumeration continues until each truth table is associated with a corresponding circuit. By sequentially increasing complexity, the first circuit associated with a particular truth table is guaranteed to be the least complex one that satisfies that functionality. However, if another circuit with the same number of promoters used is identified, it will be added to the list and considered as having multiple solutions. The enumeration can stop once all truth tables have been identified within the search space using a maximum of 9 promoters in total. Optimization for circuit compression is based on selecting the smallest circuit footprint—i.e., the fewest number of promoters—from an enumerated set of placeholder designs for a user-selected truth table. A flowchart of the algorithmic enumeration workflow is provided in the supplementary material, along with formal pseudocode for the enumeration—see Supplementary Figs. 2–17.

Lycopene assay

Cells were chemically transformed with a p15a plasmid expressing transcription factors and a pSC101 plasmid containing genes crtE, crtB, and crtI, either in an operon or under the control of individual inducible promoters. Single colonies were inoculated into 200 μL LB (with appropriate antibiotics) in a flat-bottom 96-well plate (Corning 3370) sealed with a Breath Easier membrane (Electron Microscopy Sciences 70536-20). After overnight growth (~16–20 h) in a Thermo Scientific MaxQ 4000 shaker at 300 rpm, cells were diluted 1:200 into fresh LB medium and grown for an additional 8 h. Twenty-five microlitres of cell culture was diluted into 5.1 mL of fresh LB medium in a VWR 14 mL culture tube (VWR 60818-689) with the appropriate inducer(s) and grown for 20 h. After the final growth period, 100 μL of each culture was transferred to a black-walled, clear-bottom 96-well plate (Corning 3631). OD600 absorbance was then measured using an M2e Spectramax Spectrophotometer. The remaining 5 mL cell culture was pelleted at 4800g for 10 min. The cell pellet was resuspended with 500 μL PBS and centrifuged once more at 4800g for 10 min as a washing step. The cell pellet was resuspended with 1 mL acetone and shaken at 400 rpm and 55 °C for 20 min to extract the lycopene. The final extraction was centrifuged at 4800g for 10 min to remove any cell debris. Finally, 100 μL of the supernatant was transferred to a black-walled, clear-bottom 96-well plate (Cellvis P96-1.5P), and immediately the absorbance at 470 nm wavelength was measured using an M2e Spectramax Spectrophotometer. The collected data were compared to a standard curve generated using purified lycopene (Sigma Aldrich SMB00706). Both growth and extraction procedures were performed under dark conditions.

In silico transcription and translation calculation

The RBS Calculator V2.1 was used to predict translation initiation rates (TIR)40,68. The mRNA sequences used for calculation included the ribozyme (post-cleavage), the RBS, and the full-length gene. E. coli K12 was selected as the organism. The Promoter Calculator V1.0 was used to predict transcription rates (TXR)56. The DNA sequences used for calculation included at least 100 bp of DNA upstream of the -35 box of the promoter of interest and the full-length gene. E. coli K12 was selected as the organism. The maximum forward transcription rate was used for further calculations. The TIR and TXR were multiplied to determine the relative expression level (arbitrary units).

Statistics and reproducibility

Unless otherwise specified, experiments were performed with n = 6 biological replicates across two separate days. This sample size was determined based on prior studies from our lab4,27,69 and standard practices in the literature, which typically use n = 3 biological replicates. No data were excluded from experimental analyses. Data is presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM), unless otherwise noted. Randomization was applied during site-saturation mutagenesis and phenotypic screening (see Methods—Generation of a CelR super-repressor and Error-prone PCR library construction), with threefold sampling to achieve a 95% probability of representative coverage. Investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessment.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Plasmid sequences are available from GenBank with accession numbers PV806910–PV807102. Materials generated in this study are available from the corresponding author. All data collected in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

References

-

Cox, R. S. 3rd, Surette, M. G. & Elowitz, M. B. Programming gene expression with combinatorial promoters. Mol. Syst. Biol. 3, 145 (2007).

-

Zong, D. M. et al. Predicting transcriptional output of synthetic multi-input promoters. Acs Synth. Biol. 7, 1834–1843 (2018).

-

Groseclose, T. M., Rondon, R. E., Herde, Z. D., Aldrete, C. A. & Wilson, C. J. Engineered systems of inducible anti-repressors for the next generation of biological programming. Nat. Commun. 11, 4440 (2020).

-

Rondon, R. E., Groseclose, T. M., Short, A. E. & Wilson, C. J. Transcriptional programming using engineered systems of transcription factors and genetic architectures. Nat. Commun. 10, 4784 (2019).

-

Meyer, A. J., Segall-Shapiro, T. H., Glassey, E., Zhang, J. & Voigt, C. A. Escherichia coli “Marionette” strains with 12 highly optimized small-molecule sensors. Nat. Chem. Biol. 15, 196–204 (2019).

-

Marchisio, M. A., Colaiacovo, M., Whitehead, E. & Stelling, J. Modular, rule-based modeling for the design of eukaryotic synthetic gene circuits. BMC Syst. Biol. 7, 1–11 (2013).

-

Misirli, G., Yang, B., James, K. & Wipat, A. Virtual parts repository 2: model-driven design of genetic regulatory circuits. ACS Synth. Biol. 10, 3304–3315 (2021).

-

Milner, P. T. et al. Performance prediction of fundamental transcriptional programs. ACS Synth. Biol. 12, 1094–1108 (2023).

-

Baig, H. et al. Synthetic biology open language visual (SBOL Visual) version 2.3. J. Integr. Bioinform. 18, 20200045 (2021).

-

Baig, H. et al. Synthetic biology open language visual (SBOL visual) version 3.0. J. Integr. Bioinform. 18, 20210013 (2021).

-

Baig, H. et al. Synthetic biology open language visual (SBOL visual) version 2.2. J. Integr. Bioinform. 17, 1–81 (2020).

-

Cox, R. S. et al. Synthetic Biology Open Language Visual (SBOL Visual) Version 2.0. J. Integr. Bioinform. 15, 1–66 (2018).

-

Madsen, C. et al. Synthetic Biology Open Language Visual (SBOL Visual) Version 2.1. J. Integr. Bioinform. 16, 1–77 (2019).

-

Jones, T. S., Oliveira, S. M. D., Myers, C. J., Voigt, C. A. & Densmore, D. Genetic circuit design automation with Cello 2.0. Nat. Protoc. 17, 1097–1113 (2022).

-

Nielsen, A. A. et al. Genetic circuit design automation. Science 352, aac7341 (2016).

-

Misirli, G. et al. A computational workflow for the automated generation of models of genetic designs. ACS Synth. Biol. 8, 1548–1559 (2019).

-

Roehner, N. et al. Specifying combinatorial designs with the Synthetic Biology Open Language (SBOL). ACS Synth. Biol. 8, 1519–1523 (2019).

-

Kosuri, S. et al. Composability of regulatory sequences controlling transcription and translation in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 14024–14029 (2013).

-

Lou, C., Stanton, B., Chen, Y. J., Munsky, B. & Voigt, C. A. Ribozyme-based insulator parts buffer synthetic circuits from genetic context. Nat. Biotechnol. 30, 1137–1142 (2012).

-

Şimşek, E., Yao, Y., Lee, D. & You, L. Toward predictive engineering of gene circuits. Trends Biotechnol. 41, 760–768 (2023).

-

Moon, T. S., Lou, C., Tamsir, A., Stanton, B. C. & Voigt, C. A. Genetic programs constructed from layered logic gates in single cells. Nature 491, 249–253 (2012).

-

Daniel, R., Rubens, J. R., Sarpeshkar, R. & Lu, T. K. Synthetic analog computation in living cells. Nature 497, 619–623 (2013).

-

Sexton, J. T. & Tabor, J. J. Multiplexing cell-cell communication. Mol. Syst. Biol. 16, e9618 (2020).

-

Qi, L. S. et al. Repurposing CRISPR as an RNA-guided platform for sequence-specific control of gene expression. Cell 152, 1173–1183 (2013).

-

Dong, C., Fontana, J., Patel, A., Carothers, J. M. & Zalatan, J. G. Synthetic CRISPR-Cas gene activators for transcriptional reprogramming in bacteria. Nat. Commun. 9, 2489 (2018).

-

Taketani, M. et al. Genetic circuit design automation for the gut resident species Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron. Nat. Biotechnol. 38, 962–969 (2020).

-

Huang, B. D., Groseclose, T. M. & Wilson, C. J. Transcriptional programming in a Bacteroides consortium. Nat. Commun. 13, 3901 (2022).

-

Rondon, R. E. & Wilson, C. J. Engineering a new class of anti-LacI transcription factors with alternate DNA recognition. ACS Synth. Biol. 8, 307–317 (2019).

-

Groseclose, T. M., Hersey, A. N., Huang, B. D., Realff, M. J. & Wilson, C. J. Biological signal processing filters via engineering allosteric transcription factors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2111450118 (2021).

-

Huang, B. D., Kim, D., Yu, Y. & Wilson, C. J. Engineering intelligent chassis cells via recombinase-based MEMORY circuits. Nat. Commun. 15, 2418 (2024).

-

Short, A. E., Kim, D., Milner, P. T. & Wilson, C. J. Next generation synthetic memory via intercepting recombinase function. Nat. Commun. 14, 5255 (2023).

-

Richards, D. H., Meyer, S. & Wilson, C. J. Fourteen ways to reroute cooperative communication in the lactose repressor: engineering regulatory proteins with alternate repressive functions. ACS Synth. Biol. 6, 6–12 (2017).

-

Mangan, S. & Alon, U. Structure and function of the feed-forward loop network motif. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 11980–11985 (2003).

-

Duan, Y. T. et al. Deciphering the rules of ribosome binding site differentiation in context dependence. ACS Synth. Biol. 11, 2726–2740 (2022).

-

Kelly, J. R. et al. Measuring the activity of BioBrick promoters using an in vivo reference standard. J. Biol. Eng. 3, 4 (2009).

-

Zhang, Y., Ding, W., Wang, Z., Zhao, H. & Shi, S. Development of host-orthogonal genetic systems for synthetic biology. Adv. Biol. (Weinh.) 5, e2000252 (2021).

-

Cardinale, S. & Arkin, A. P. Contextualizing context for synthetic biology-identifying causes of failure of synthetic biological systems. Biotechnol. J. 7, 856–866 (2012).

-

Wang, B., Kitney, R. I., Joly, N. & Buck, M. Engineering modular and orthogonal genetic logic gates for robust digital-like synthetic biology. Nat. Commun. 2, 508 (2011).

-

Yeung, E. et al. Biophysical constraints arising from compositional context in synthetic gene networks. Cell Syst. 5, 11–24.e12 (2017).

-

Salis, H. M., Mirsky, E. A. & Voigt, C. A. Automated design of synthetic ribosome binding sites to control protein expression. Nat. Biotechnol. 27, 946–950 (2009).

-

Seo, S. W. et al. Predictive design of mRNA translation initiation region to control prokaryotic translation efficiency. Metab. Eng. 15, 67–74 (2013).

-

Tamsir, A., Tabor, J. J. & Voigt, C. A. Robust multicellular computing using genetically encoded NOR gates and chemical ‘wires’. Nature 469, 212–215 (2011).

-

Scharle, T. W. Axiomatization of propositional calculus with Sheffer functors. Notre Dame J. Form. Log. 6, 209–217 (1965).

-

Misawa, N. et al. Elucidation of the Erwinia uredovora carotenoid biosynthetic pathway by functional analysis of gene products expressed in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 172, 6704–6712 (1990).

-

Cunningham, F. X. Jr., Sun, Z., Chamovitz, D., Hirschberg, J. & Gantt, E. Molecular structure and enzymatic function of lycopene cyclase from the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp strain PCC7942. Plant Cell 6, 1107–1121 (1994).

-

Kim, S. W. & Keasling, J. D. Metabolic engineering of the nonmevalonate isopentenyl diphosphate synthesis pathway in Escherichia coli enhances lycopene production. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 72, 408–415 (2001).

-

Sun, T. et al. Production of lycopene by metabolically-engineered Escherichia coli. Biotechnol. Lett. 36, 1515–1522 (2014).

-

Miguez, A. M., McNerney, M. P. & Styczynski, M. P. Metabolomics analysis of the toxic effects of the production of lycopene and its precursors. Front. Microbiol 9, 760 (2018).

-

Yoon, K. W., Doo, E. H., Kim, S. W. & Park, J. B. In situ recovery of lycopene during biosynthesis with recombinant Escherichia coli. J. Biotechnol. 135, 291–294 (2008).

-

Albermann, C. High versus low level expression of the lycopene biosynthesis genes from Pantoea ananatis in Escherichia coli. Biotechnol. Lett. 33, 313–319 (2011).

-

Gallego-Jara, J. et al. Lycopene overproduction and in situ extraction in organic-aqueous culture systems using a metabolically engineered Escherichia coli. AMB Express 5, 65 (2015).

-

Hersey, A. N., Kay, V. E., Lee, S., Realff, M. J. & Wilson, C. J. Engineering allosteric transcription factors guided by the LacI topology. Cell Syst. 14, 645–655 (2023).

-

Zrimec, J. et al. Controlling gene expression with deep generative design of regulatory DNA. Nat. Commun. 13, 5099 (2022).

-

Zhang, P. et al. Deep flanking sequence engineering for efficient promoter design using DeepSEED. Nat. Commun. 14, 6309 (2023).

-

Van Brempt, M. et al. Predictive design of sigma factor-specific promoters. Nat. Commun. 11, 5822 (2020).

-

LaFleur, T. L., Hossain, A. & Salis, H. M. Automated model-predictive design of synthetic promoters to control transcriptional profiles in bacteria. Nat. Commun. 13, 5159 (2022).

-

Nielsen, A. A. & Voigt, C. A. Multi-input CRISPR/Cas genetic circuits that interface host regulatory networks. Mol. Syst. Biol. 10, 763 (2014).

-

Green, A. A. et al. Complex cellular logic computation using ribocomputing devices. Nature 548, 117–121 (2017).

-

Higashikuni, Y., Chen, W. C. & Lu, T. K. Advancing therapeutic applications of synthetic gene circuits. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 47, 133–141 (2017).

-

Hong, M., Clubb, J. D. & Chen, Y. Y. Engineering CAR-T cells for next-generation cancer therapy. Cancer Cell 38, 473–488 (2020).

-

Cubillos-Ruiz, A. et al. Engineering living therapeutics with synthetic biology. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 20, 941–960 (2021).

-

González, L. M., Mukhitov, N. & Voigt, C. A. Resilient living materials built by printing bacterial spores. Nat. Chem. Biol. 16, 126–133 (2020).

-

McCarty, N. S. & Ledesma-Amaro, R. Synthetic biology tools to engineer microbial communities for biotechnology. Trends Biotechnol. 37, 181–197 (2019).

-

Khalil, A. S. & Collins, J. J. Synthetic biology: applications come of age. Nat. Rev. Genet. 11, 367–379 (2010).

-

Voigt, C. A. Synthetic biology 2020-2030: six commercially-available products that are changing our world. Nat. Commun. 11, 6379 (2020).

-

Engler, C., Kandzia, R. & Marillonnet, S. A one pot, one step, precision cloning method with high throughput capability. PLoS ONE 3, e3647 (2008).

-

Gibson, D. G. et al. Enzymatic assembly of DNA molecules up to several hundred kilobases. Nat. Methods 6, 343–345 (2009).

-

Reis, A. C. & Salis, H. M. An automated model test system for systematic development and improvement of gene expression models. ACS Synth. Biol. 9, 3145–3156 (2020).

-

Groseclose, T. M., Rondon, R. E., Herde, Z. D., Aldrete, C. A. & Wilson, C. J. Engineered systems of inducible anti-repressors for the next generation of biological programming. Nat. Commun. 11, 1–15 (2020).

-

Huang, B. D. et al. Engineering wetware and software for the predictive design of compressed genetic circuits for higher-state decision-making. Zenodo 10.5281/zenodo.16988958 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Science Foundation grant numbers 1934836, 2123855, 2226663, 2319231, and the National Institute of Health grant number R35GM153457 (all awarded to C.J.W.). We would like to thank M. Styczynski (Georgia Tech) for the plasmid containing the crtEBI genes.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Dae-Hee Lee, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, B.D., Yu, Y., Lee, J. et al. Engineering wetware and software for the predictive design of compressed genetic circuits for higher-state decision-making. Nat Commun 16, 9414 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64457-0

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64457-0