- Article

- Open access

- Published:

Scientific Reports volume 15, Article number: 44583 (2025) Cite this article

Subjects

Abstract

Inflammation and oxidative stress are key pathological drivers of many chronic and neurodegenerative disorders, prompting increasing interest in natural compounds that can safely modulate inflammatory responses and protect neural cells from oxidative damage. In this study, walnut shell pectin (WSP), extracted from Chilean walnut shells, was evaluated for its anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective potential using in vitro models. The anti-inflammatory effects were assessed in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages, while the neuroprotective effects were investigated in rotenone-treated SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells. WSP significantly reduced LPS-induced inflammation by downregulating the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α and enhancing the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10. In rotenone-exposed SH-SY5Y cells, WSP increased the activities of antioxidant enzymes, catalase and superoxide dismutase, thereby reducing oxidative stress and improving neuronal viability. The maximum protective concentration for both cell lines was determined to be 50 µg/ml. Overall, WSP exhibited strong anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective activities in vitro, highlighting its potential as a natural therapeutic compound for preventing and managing inflammation-associated and neurodegenerative disorders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pectin is a heterogenous polysaccharide which is present naturally in the cell walls of fruits and vegetables. It is extensively present in the primary cell wall and middle lamella providing mechanical strength and acting as a barrier against external environment for the plants1. The functional groups present in the pectin offers various functionalities and modification of these functional groups can have novel applications as they undergo various physio-chemical changes2. The structural and molecular characteristics of pectin are the foundation for its application in food and healthcare industries3. In industrial scale, pectin is majorly extracted from citrus peels, sugar beet and apple pomace1,2,4. Current studies focus on using agricultural residues such as walnut husk5, walnut shell6, coffee husk7, coffee pulp8, mango peels9, banana peel10, and cocoa pods11 for the extraction of pectin. Pectin extracted from the agricultural residue has demonstrated anti-inflammatory nature by interacting with immune cells such as macrophages and T cells, inhibiting their activation and proliferation, thereby reducing inflammation12,13. They exhibit anti-diabetic14,15, anticancer16, antioxidant17 and immunomodulatory properties18 in vivo as well as in vitro. It is commonly used as a source of dietary fibre in both animal and human nutrition19,20. Various studies showed that pectin can regulate the gut microbiota, thereby reducing inflammation, and protect against oxidative stress21,22,23,24. The anti-inflammatory effects of pectin have been demonstrated in various research studies. For example, the pectin extracted from Okra has shown the suppression of nitrous oxide production in lipo- polysaccharide (LPS) induced RAW 264.7 cells thus exhibiting the anti-inflammatory property25. The modified citrus pectin which is a natural antagonist of Galectin-3, a pro-inflammatory cytokine, delivered by collagen-membrane system significantly increased the articular cartilage defect repair26. Distinct structural characteristics of pectin enables it to interact with immune cells and alter the gut microbiota, are thought to be responsible for its anti-inflammatory properties. Pectin is also emerged as a potential neuroprotective compound, exhibiting a range of biological activities that may contribute to the prevention and treatment of neurodegenerative diseases27,28. One of the key mechanisms by which pectin has neuroprotective benefits is via altering the gut-brain axis, a bidirectional communication network between the enteric nervous system and the central nervous system (CNS)29. In the presence of healthy gut bacteria, the pectin ferments to form short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) such acetate, propionate, and butyrate. These SCFAs have been proved to express neuroprotective effects and to traverse the blood–brain barrier30. For instance, research has shown that SCFAs can inhibit pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), which are associated with the onset of neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease31. Additionally, pectin has also been proved to directly interact with immune cells, such as microglia, inhibiting their activation and proliferation, thereby reducing neuroinflammation32,33. The neuroprotective effects of pectin have also been linked to its antioxidant qualities, which allow it to diminish oxidative stress and scavenge reactive oxygen species, two major factors in the pathophysiology of neurodegenerative diseases. It has also been demonstrated that pectin alters the expression of genes related to neuroprotection, including those that code for antioxidant enzymes like superoxide dismutase (SOD)34. Various in vitro and in vivo investigations demonstrated the neuroprotective benefits of pectin. The impact of modified citrus pectin on dementia in adult male Wistar rats was evaluated using the scopolamine-induced Alzheimer’s paradigm35,36,37. In another study lemon IntegroPectin was shown to significantly enhance the neuroprotective and mitoprotective effects on H2O2 induced human SH-SY5Y cells38 . Further, the effect of pectin supplementation on cognition, depression-like behavior, and memory in mice models was investigated, highlighting how elevated interleukin-6 (IL-6) levels in the hippocampus contributed to improved recognition memory and antidepressant-like behaviors39. This study aim ed in investigating the anti-inflammatory ability and neuroprotective effects of WSP, exploring its potential as a novel therapeutic agent for the prevention and treatment of chronic diseases.

Materials and methods

Walnut shell pectin (WSP) preparation and characterization

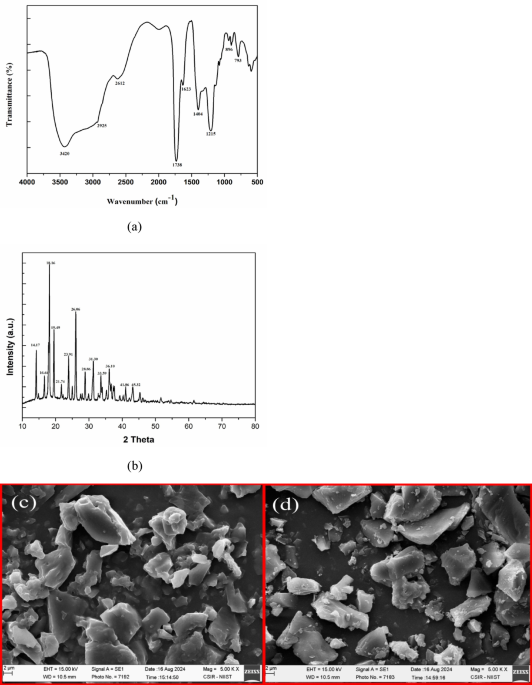

A 100 µg/ml stock solution was prepared using WSP extracted from Chilean walnut shell, as described in our previous study6 and the solution was filter sterilized using 0.4 µm filters and stored below 4 ˚C for further use. The major functional groups present in the extracted WSP were characterized using Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) using Bruker Alpha ECO-ATR (Bruker, Karlsruhe, Germany) in the frequency range of 4000–400 cm⁻1 at a resolution of 4 cm⁻1 per second using the ATR method. Additionally, the structural nature of WSP was analysed using X-ray diffraction (XRD) with a Bruker D8 Advance Diffractometer (Bruker, Germany), covering a diffraction angle range of 5°–50° (2θ) and using SEM (Carl Zeiss- ULTRA 55, Germany).

Evaluation of anti-inflammatory property of WSP

The cytotoxic potential of WSP was assessed on RAW 264.7 cells (murine macrophage cells) procured from NCCS, Pune. The RAW 264.7 cells were cultured at 37 °C with CO2 (5 %) atmosphere in DMEM supplemented with high glucose (4.5 g/l), 1 % L-glutamine, 1 % antibiotic–antimycotic solution (containing 10,000 U/ml penicillin, 10 mg/ml streptomycin, and 25 µg/ml amphotericin B) and 10 % FBS.

Cell viability assay

The RAW 246.7 cells were cultured in a 96-well plate with a cell density of 2 × 104 cells/well and incubated for 24 h . To induce inflammation, the cells were subsequently exposed to LPS (1 µg/ml) for 4 h and then the cells were treated with different doses of WSP (6.25–100 µg/ml) and incubated at 37 °C in CO2 (5 %) for 24 h and the MTT assay was performed to assess the cell viability with slight modification40. Briefly, 50 µl of MTT (0.5 mg/ml) was added to each well after the spent medium was taken out of the incubated cells and covered with aluminium foil to avoid exposure to the light. The cells were then cultured for 3 h at 37 °C. After removing the solution, each well was added with 100 µl of DMSO and placed on a gyratory shaker to dissolve the formazan crystals. The cell viability was calculated and expressed as percentage using Eq. 1 after recording the absorbance at 570 nm wavelength using an ELISA reader (VersaMax ELISA Microplate Reader, Molecular Devices, California, USA).

$$text{Cell viability (%) = }frac{text{absorbance of the treated cells}}{text{absorbance of the untreated cells}}text{ X 100}$$

(1)

Determination of anti-inflammatory effect of WSP on RAW 264.7 cells

Furthermore, WSP’s anti-inflammatory effects on LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells were assessed. Briefly, 5 × 105 cells/ml of the cells were grown in a 6-well plate, and they were incubated for 24 h at 37 °C in a CO2 (5 %) environment. After inducing inflammation with LPS (1 µg/ml) for 4 h41, the cells were treated with WSP (50 µg/ml) and incubated for 24 h. The LPS treated cells were used as a positive control, whereas the untreated cells served as a negative control. The standard anti-inflammatory drug used was a non-steroidal diclofenac (1 mM)42. After treatment, cells were washed with PBS and fixed by adding 1 ml of chilled ethanol (70 %). Following fixation, the cells were washed twice with PBS, and the percentages of cells expressing IL-10 and TNF-α were measured using specific antibodies. Flow cytometry using FACS Calibur (BD Biosciences, CA, USA) was used to determine the TNF-α and IL-10 expression. The results were then analysed by the program BD Cell Quest Pro ver. 6.0.

Evaluation of neuroprotective property of WSP

Cell culture of SH-SY5Y cells

SH-SY5Y (human neuroblastoma cells) cells procured from NCCS, Pune were cultured in DMEM supplemented with high glucose (4.5 g/l), 1 % L-glutamine, 1 % antibiotic–antimycotic solution (containing 10,000 U/ml penicillin, 10 mg/ml streptomycin, and 25 µg/ml amphotericin B), and 10 % FBS. The cells were maintained in a humidified incubator at 37 °C with a 5 % CO₂ atmosphere.

Cell viability assay

The cytotoxicity of WSP on SH-SY5Y cells was evaluated using the MTT assay. In brief, The SH-SY5Y cells were cultured in 96-well plates with a cell density of 2 × 104 cells/well and allowed to proliferate for 24 h in order to assess the cell viability. Rotenone (100 µM) was then administered to the cells for 4 h in order to induce neurotoxicity. Further, the cells were treated with different doses of WSP (6.25–100 µg/ml) and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C in CO2 (5 %) environment. MTT test was performed to evaluate the cell viability with minor modifications40. After removing the spent medium from the cultured cells, 50 µl of MTT (0.5 mg/ml) was added to each well and shielded from the light using aluminium foil and the cells were incubated for 3 h at 37 °C. After removing the solution, each well was added with 100 µl of DMSO and placed on a gyratory shaker to dissolve the formazan crystals. Absorbance was measured at 570 nm wavelength using ELISA reader (VersaMax ELISA Microplate Reader, Molecular Devices, California, USA) and the percentage of cell viability was calculated using the Eq. 1.

Determination of antioxidant activity of WSP on SH-SY5Y cells

The cellular antioxidant activity of WSP was assessed against SH-SY5Y cells. In summary, 5 × 105 cells/ml of SH-SY5Y cells were taken in a 12-well plate and cultured for 48 h to achieve the required cell density and cell attachment43. Further, the cells were treated with 100 µM rotenone for 2 h to induce neurotoxicity followed by treatment with different concentrations of WSP (6.25–100 µg/ml). The cells that underwent just rotenone treatment were regarded as positive or disease control, whereas the untreated cells were considered as negative control. Cells were cultured for 24 h at 37 °C in an incubator with CO2 (5 %). The GENLISA Human Catalase ELISA Kit (KrishGen Biosystems, India) was used to evaluate the catalase activity according to Abei’s technique, and the SOD assay kit (Elabscience, USA) was used to detect the SOD activity colorimetrically.

Later, the fluorogenic dye 2’,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2-DCFDA), a commonly used ROS indicator, was used to measure intracellular ROS produced by the cells. In brief, the SH-SY5Y cells were cultured at a cell density of 0.5 × 106 cells/ml on a 35 mm glass bottom dish and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C in a CO2 (5 %) incubator. After 2 h of treatment with 100 µM Rotenone, the cells were treated with a standard drug Resveratrol (50 µm) and 50 µg/ml of WSP, and incubated for 24 h. The cells that underwent just rotenone treatment were considered as positive or disease control, whereas the untreated cells were considered as negative control. Following incubation, the cells were rinsed with PBS solution and the medium was removed. Furthermore, the cells were treated with 10 µM H2-DCFDA solution and incubated in dark for 30 min. Following the removal of the dye, the cells were counterstained with 1 ml of 10 µg/ml Hoechst 33,342 dye and incubated for 15 min, and then rinsed with 1 ml of PBS. Following that, the cells were examined using a ZEISS LSM 880 Fluorescence live cell imaging system (Confocal Microscopy) equipped with a filter cube and a 488 nm wavelength and detection at 535 nm wavelength . Carl Zeiss ZEN Blue software 2.3 (Carl Zeiss, Germany) was used to analyse the images and Image J 2.0 1.53 k (Wayne Rasband and contributors, National Institute of Health, USA) (http://imagej.nih.gov/ij) software was used to assess the expression of DCF intensity.

Statistical analysis

Each experiment was carried out in triplicates. GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) was used to analyze the data. One-way ANOVA was used to establish statistical significance and the findings represented as mean ± standard deviation.

Results

Characterization of walnut shell pectin

The FTIR spectra of walnut shell pectin (Fig. 1a) exhibited distinct characteristic peaks at 3420 cm⁻1 and 2925 cm⁻1, corresponding to the stretching vibrations of -OH and C-H bonds, respectively. The absorption peak at 1738 cm⁻1 is associated with the C = O stretching vibration of the esterified carboxyl group, while the peak at 1623 cm⁻1 is attributed to the C = O stretching vibration of the carboxylate ion. The fingerprint region, spanning 800 to 1300 cm⁻1, reflects the presence of carbohydrate groups in the polysaccharides. Additionally, the absorption band within 1200–1000 cm⁻1 corresponds to C–O–C vibrations of glycosides. These findings align with our previous research on walnut shell pectin, demonstrating the consistency and repeatability of the structure of pectin6.

(a) FTIR spectrum of Walnut shell pectin. (b) : XRD pattern of Walnut shell pectin. SEM images of (c) Commercial pectin and (d) Walnut shell pectin.

The X-ray diffractogram of the extracted pectin is shown in Fig. 1b. Presence of sharp peaks at 14.17, 16.64, 18.16, 19.49, 21.74, 23.91, 26.06, 28.86, 31.30, 33.59, 36.10, 41.06, and 45.31° (2θ) confirm ed the crystalline nature of the pectin samples. These results were consistent with our previous study on WSP, demonstrating the repeatability of the findings6.

The surface morphology of WSP was analysed and characterised by SEM and compared with the commercial pectin (Fig. 1c and d). Morphology of pectin is influenced by the extraction techniques and the source of extraction44. The solvent extraction method makes it appear as irregular shaped aggregates due to rapid precipitation45. The microwave assisted extraction of pectin from walnut shell appears to be flaky, rough and slightly ruptured because of the high internal pressure and rapid increase in temperature46,47. Similar findings for the pectin extracted from Kinnow peel were also reported by earlier studies48.

Cell viability of RAW264.7 cells

The role of pectin extracted from different sources in treating inflammation have been reported in earlier studies22,25,49. Before assessing the anti-inflammatory effect of WSP, their cytotoxic effect on cell growth and cell viability were studied in RAW 264.7 cells by MTT assay. RAW 264.7 cells are monocytes or macrophage-like cells that are obtained from a BALB/c mouse cell line that has been altered by the Abelson leukemia virus50. These cell lines are widely used monocyte/macrophage models for both in vivo and in vitro anti-inflammatory studies51. Cell viability of the pectin extracted from walnut shell was > 75 % at concentrations of 25 µg/m l and below (Fig. 2). However, 50 and 100 µg/m l concentrations of WSP showed a toxicity effect, with cell viability at 100 µg/ml WSP found to be 64.40 %. This data indicated that the viability of RAW 264.7 cells decreased with increasing concentrations of WSP, demonstrating concentration-dependent cytotoxicity. Pectin extracted from raspberry52, Saussurea laniceps53, Kiwanos54 also showed similar results on RAW 264.7 cells.

Impact of varying concentration of walnut shell pectin on RAW 264.7 cell viability. Concentration range (6.25 µg/ml–100 µg/ml). Data represents mean ± SD, n = 3. (Tukey test: **p > 0.001 and ***p > 0.0001 when compared with untreated cells).

Anti-inflammatory activity of walnut shell pectin on RAW 264.7 cells

The ability of WSP to reduce inflammation was evaluated using RAW 264.7 cells stimulated by LPS. LPS is found in the cell wall of gram-negative bacteria, which are frequently employed to create inflammatory models of monocytes and macrophages in order to evaluate the anti-inflammatory properties of substances derived from different sources. Pro-inflammatory cytokines including TNF-α, interleukin-β (IL-β), and interleukin-6 (IL-6) are all expressed in response to LPS, along with other inflammatory mediators such prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and nitric oxide (NO)55. When RAW 264.7 cells were treated with 1 µg/ml of LPS, their viability decreased by 69.8 % compared to untreated cells. Treatment with standard diclofenac (1 mM) in LPS-induced cells resulted in a viability of 73.58 %. In contrast, various doses of WSP enhanced cell viability, with 50 µg/ml achieving 65.66 %. However, at a concentration of 100 µg/ml, cell viability dropped to 52.77 %, indicating that 50 µg/ml WSP provided the optimal protective effect on LPS-treated RAW 264.7 cells as shown in Fig. 3.

Inhibition of cytotoxicity on LPS induced RAW 264.7 cells by varying concentration of walnut shell pectin Concentration range (6.25 µg/ml–100 µg/ml). Data represents mean ± SD, n = 3. (Tukey test: #p > 0.0001 when compared with untreated cells; ***p > 0.001 when compared with LPS induced cells; **p > 0.0001 when compared with standard drug).

The morphology of RAW 264.7 cell before and after treatment with LPS and WSP can be seen in (Fig. 4). Figure 4a depicts the morphology of untreated RAW 264.7 cells, which are round, viable, smooth spindle-shaped cells that are loosely adherent. Exposure of cells to LPS has induced toxicity and changed its morphology and caused a cell shrinkage (Fig. 4b). Whereas LPS stimulated cells when treated with WSP reduced the inflammation (Fig. 4d) and shown similar morphology as that of LPS stimulated cells treated with standard diclofenac (1 mM) (Fig. 4c). These data suggest the potential of WSP in preventing cell damage caused by LPS and thus showing its anti-inflammatory effect56 made the similar observation where enzyme treated citrus pectin showed no inhibition on cell growth up to the concentration of 200 µg/ml and decreased the production of nitric acid in LPS induced cells. Further, the observation was also made, where LPS induced RAW 264.7 cells exhibited irregular shapes and pseudopodia formation which reduced when exposed to enzyme treated citrus pectin.

Morphology of RAW264.7 cells. (a) Untreated RAW 264.7 cells (b) RAW 264.7 cells exposed to Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (1 µg/ml) (c) RAW 264.7 induced with Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (1 µg/ml) and exposed to standard drug diclofenac (1 mM) (d) RAW 264.7 cells induced with Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (1 µg/ml) and exposed to 50 µg/ml walnut shell pectin .

Anti-inflammatory activity using flow cytometry

LPS stimulates various signalling pathways in macrophages including NF-kB/1KK signalling which plays a significant role in upregulation of several proinflammatory cytokines like TNF-α, TNF-β and IL-6 57,58. Activation of NF-kB in the pathogenesis of inflammatory diseases makes it a target to study the anti-inflammatory effects of drugs and other natural compounds. In this study, the anti-inflammatory impact of WSP on TNF-α and IL-10 expression in RAW 264.7 cells stimulated by LPS was assessed. The histogram of TNF-α expression is displayed in (Fig. 5), with M1 denoting a negative expression zone where cells do not express TNF-α and M2 denoting a positive expression region where cells are expressing TNF-α. LPS-induced RAW 264.7 cells expressed more pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α, whereas, the treatment with WSP and standard diclofenac reduced TNF-α levels. In (Fig. 6), increase in the TNF-α expression (77.3 %) was observed with the cells induced with LPS, which was significantly inhibited when treated with standard diclofenac (38.15 %) and WSP (52.97 %). Similarly, observation was done for IL-10 expression which is a potent anti-inflammatory cytokine that plays a significant role in preventing inflammation and autoimmune pathogenesis 59,60. The histogram of IL-10 expression demonstrated that LPS induced cells shows negative expression of IL-10 in M1 region whereas, the diclofenac and WSP treated cells has shown positive expression of IL-10 in M2 region (Fig. 7). Figure 8 shows the least expression of IL-10 (1.36 %) in LPS induced RAW 264.7 cells and increase in IL-10 expression was observed for the cells treated with diclofenac (51.43 %) and WSP (38.46 %). These findings shows that WSP can decrease the inflammatory effect by increasing IL-10 expression and thus lowering the production of the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α in LPS induced RAW 264.7 cells. The results are in line with the results reported for sweet potato residue pectin 12.

Effect of walnut shell pectin on TNF- α expression against Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) induced RAW 264.7 cells. (a) Untreated cells, (b) LPS induced cells (1 µg/ml), (c) LPS induced cells treated with standard drug diclofenac (1 mM), (d) LPS induced cells treated with WSP (50 µg/ml), and (e) Overlay image. IL-10 histogram of the gated RAW 264.7 singlets distinguish cells at M1 and M2 regions. (M1 refers to the negative region/expression and M2 refers to the positive region/expression). Gating of M1 and M2 is approximate and can be refined using CellQuest Pro Software, Version 6.0 software. % cells observed in M2 region is considered as TNF- α expression in present study.

Percentage of RAW 264.7 cells expressing TNF- α. Data represents mean ± SD, n = 3. (Tukey test: *p > 0.0001 when compared with untreated cells; **p > 0.001 when compared with LPS induced cells; ***p > 0.0001 when compared with standard drug).

Effect of walnut shell pectin on IL-10 expression against Lipopolysaccharide induced RAW 264.7 cells. (a) Untreated cells, (b) LPS induced cells (1 µg/ml), (c) LPS induced cells treated with standard drug diclofenac (1 mM), (d) LPS induced cells treated with WSP (50 µg/ml), and (e) Overlay image. IL-10 histogram of the gated RAW 264.7 singlets distinguish cells at M1 and M2 regions. (M1 refers to the negative region/expression and M2 refers to the positive region/expression). Gating of M1 and M2 is approximate and can be refined using CellQuest Pro Software, Version 6.0 software. % cells observed in M2 region was considered as IL-10 expression in present study.

Percentage of RAW 264.7 cells expressing IL-10. Data represents mean ± SD, n = 3. (Tukey test: **p > 0.001 when compared with LPS induced cells; ***p > 0.0001 when compared with standard drug).

Cell viability on SH-SY5Y cells

The role of pectin extracted from different sources in treating inflammation have been reported in many research studies 61,62. Before assessing the neuro protective effect of WSP, their cytotoxic effect on cell growth and cell viability was studied in SH-SY5Y cells by MTT assay. The most widely used neuronal cell line, SH-SY5Y was derived from the SK-N-SH cell line which was created in 1970 from a metastatic bone marrow biopsy of a 4-year-old child suffering with neuroblastoma 63. The WSP showed cell viability more than 75 % at concentration 25 µg/ml and below (Fig. 9). However, at 50 and 100 µg/ml, WSP showed a toxicity effect and the cell viability at 100 µg/ml WSP was found to be 64.40 %. This data indicated that the WSP is an excellent biocompatible substance that has no effect on the viability of RAW 264.7 cells at concentrations between 0 and 25 µg/ml.

Effect of walnut shell pectin on cell viability of SH-SY5Y cells. Data represents mean ± SD, n = 3 (Tukey test: *p > 0.0001 when compared with untreated cells).

Furthermore, rotenone impaired SH-SY5Y cell viability by inhibiting mitochondrial complex I, which led to ATP depletion, increased oxidative stress, and subsequent cellular damage. This disruption triggered apoptosis and compromised overall cell function 64. In contrast, cells treated with different concentrations of WSP showed the increase in cell viability reaching maximum of 56.86 ± 0.2 % at 50 µg/ml. However, a decline at 100 µg/ml suggests that 50 µg/ml is the optimal protective dose on SH-SY5Y cells (Fig. 10).

Inhibition of cytotoxicity on rotenone induced SH-SY5Y cells by walnut shell pectin . Data represents mean ± SD, n = 3 (Tukey test: **p > 0.001 when compared with untreated cells; ***p > 0.0001 when compared with standard drug).

Cellular antioxidant ability on SH-SY5Y cells

Activation of antioxidant enzymes such as SOD and CAT is known to reduce the cell damage induced by rotenone and restore the cell state similar to the untreated cells in SH-SY5Y cells 65. In SH-SY5Y cells exposed to rotenone-induced oxidative stress, the cellular antioxidant capacity of WSP was evaluated for the enzymes SOD and CAT. The SOD and CAT activities of the untreated cells were 1808.91 ± 99.76 and 9.28 ± 0.16 ng/ml, respectively but the rotenone induced cells had shown significant decrease of SOD (114.88 ± 10.31 pg/ml) and CAT (1.67 ± 0.25 ng/ml) activities aiding in induction of oxidative stress. Whereas the rotenone induced cells when treated with WSP (50 µg/ml) as shown elevation in the SOD and CAT levels to 1027.11 ± 11.41 pg/ml and 5.82 ± 0.16 ng/ml respectively which are comparable with the untreated cells indicating the reduction of oxidative stress induced by rotenone on SH-SY5Y cells by WSP (Figs. 11 and 12). These results align with previous studies on grapefruit 38 and lemon IntegroPectin 66, indicating that pretreatment or co-treatment with IntegroPectin prevents H₂O₂-induced mitochondrial dysfunction. This suggests that its scavenging effect extends to mitochondrial ROS, effectively delaying ROS production in H₂O₂-induced SH-SY5Y cells and playing a protective role in cellular function.

Effect of walnut shell pectin on Superoxide dismutase ) activity in Rotenone (100 µM) induced SH-SY5Y cells. Data represent ed mean ± SD, n = 3 (Tukey test: **p > 0.001 when compared with untreated cells; ***p > 0.0001 when compared with rotenone induced cells).

Effect of walnut shell pectin on Catalase activity in Rotenone (100 µM) induced SH-SY5Y cells. Data represent ed mean ± SD, n = 3 (Tukey test: **p > 0.001 when compared with untreated cells; ***p > 0.0001 when compared with rotenone induced cells).

Quantification of intracellular ROS using confocal microscopy

The DCFH-DA fluorescence intensity assay was used to measure ROS generation in order to evaluate the effect of WSP on rotenone-induced oxidative stress in SH-SY5Y cells. Fluorescence microscope examination (Fig. 13) and fluorescence intensity measurement (Fig. 14) shows the impact of WSP on SH-SY5Y in reducing the ROS rise caused by rotenone induction as compared to cells treated with rotenone alone. The DCF intensity of untreated cells is 0.048 ± 0.001 whereas the cells induced with rotenone had DCF intensity of 4.805 ± 1.64. Furthermore, the rotenone induced cells when treated with WSP (50 µg/ml) exhibited reduced intensity of 0.26 ± 0.109 which is almost closer to the DCF intensity of untreated cells (0.048 ± 0.001), suggesting the antioxidant potential of WSP on stress induced SH-SY5Y cells. The results are in line with the evidences reported from the previous studies wherein grapefruit IntegroPectin 38 Hibiscus syriacus Linn. 67 was effective in reducing the ROS formation induced by H2O2 thus increasing the antioxidant activity in the neuronal cells. Pectin from various sources increases the activity of antioxidant enzymes, providing a potential strategy to fight oxidative stress and enhance overall well-being.

Effect of walnut shell pectin on levels of intracellular reactive oxygen species for rotenone (100 µM) induced SH-SY5Y cells. Data represent ed mean ± SD, n = 3 (Tukey test: **p > 0.001 when compared with untreated cells; ***p > 0.0001 when compared with rotenone induced cells).

Fluorescence microscope images showing DCF expression in SH-SY5Y cells under three conditions: untreated, rotenone-treated, and rotenone + WSP treated at 40 X magnification.

Discussion

WSP has emerged as a promising biopolymer with significant structural and biological properties, making it a valuable candidate for biomedical applications. Comprehensive analyses, including FTIR, XRD, SEM and various cell-based assays, have provided insights into its composition, morphology, and functional activities. FTIR analysis revealed characteristic peaks indicative of hydroxyl (-OH), carbonyl (C = O), and glycosidic (C–O–C) groups, confirming the polysaccharide nature of WSP. Similar spectral profiles have been reported for pectins extracted from citrus and apple peels, where these functional groups contributed to strong gelling and bioactive properties 6,68,69. The XRD pattern exhibited sharp peaks, suggesting a crystalline structure typical of pectin 6. Such semi-crystalline behaviour is commonly associated with enhanced mechanical strength and stability in biopolymers 70. SEM imaging further illustrated the morphological differences between WSP and commercial pectin, with WSP displaying a flaky and rough surface, potentially due to the extraction method employed 46,47. Biologically, WSP demonstrated notable cytocompatibility in RAW 264.7 macrophage cells, with cell viability exceeding 75 % at concentrations up to 25 µg/ml. However, higher concentrations (50 and 100 µg/ml) exhibited dose-dependent cytotoxicity which aligns with the concentration-dependent responses observed in other natural polysaccharides 71. In LPS-induced inflammatory models, WSP treatment enhanced cell viability and reduced the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α and IL-6, while promoting the expression of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10. These effects were comparable to those observed with the standard anti-inflammatory drug diclofenac consistent with prior reports of pectin-derived polysaccharides exhibiting immunomodulatory potential 72. In neuronal SH-SY5Y cells, WSP exhibited protective effects against rotenone-induced toxicity, a model for neurodegenerative diseases. At concentrations up to 50 µg/ml, WSP improved cell viability and restored antioxidant enzyme activities, including superoxide SOD and CAT, to levels comparable with untreated cells. Additionally, WSP treatment reduced intracellular ROS levels, indicating its potential as an antioxidant agent. These neuroprotective effects are in agreement with previous findings showing pectin-based polysaccharides mitigate oxidative stress and neuronal apoptosis through scavenging of free radicals and modulation of redox signaling pathways 73,74. Collectively, these findings underscore the multifaceted bioactivity of WSP, encompassing anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective properties, attributed to its structural composition and functional groups. The promising results from this study suggest that WSP could serve as a valuable natural polymer in biomedical applications, particularly in the development of therapeutic agents targeting inflammation and oxidative stress-related conditions.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated the significant anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects of walnut shell pectin. The findings suggested that walnut shell pectin effectively reduces oxidative stress and inflammation, thereby mitigating neuronal damage and the maximum protective dosage of WSP on RAW 264.7 cells and SH-SY5Y cells was found to be 50 µg/ml. Its protective role may be attributed to its ability to modulate key inflammatory pathways by controlling the expression of TNF-α and IL-10 cytokines thus enhancing cellular defence mechanisms. Furthermore, WSP showed a significant neuroprotective effect by increasing the superoxidase dismutase and catalase enzyme activity thus reducing the oxidative stress in SH-SY5Y cells. In brief, we can conclude that WSP can be a potential therapeutic compound for treating inflammation, mitigating oxidative stress and improving mental health.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

-

Salima, B., Seloua, D., Djamel, F. & Samir, M. Structure of pumpkin pectin and its effect on its technological properties. Appl. Rheol. 32(1), 34–55. https://doi.org/10.1515/arh-2022-0124 (2022).

-

Freitas, C. M. P., Coimbra, J. S. R., Souza, V. G. L. & Sousa, R. C. S. Structure and applications of pectin in food, biomedical, and pharmaceutical industry: A review. Coatings 11(8), 922. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings11080922 (2021).

-

Kumar, M. et al. Emerging trends in pectin extraction and its anti-microbial functionalization using natural bioactives for application in food packaging. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 105, 223–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2020.09.009 (2020).

-

Gołębiewska, E., Kalinowska, M. & Yildiz, G. Sustainable use of apple pomace (AP) in different industrial sectors. Materials 15(5), 1788. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15051788 (2022).

-

La Torre, C., Caputo, P., Plastina, P., Cione, E. & Fazio, A. Green husk of walnuts (Juglans regia l.) from southern Italy as a valuable source for the recovery of glucans and pectins. Fermentation https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation7040305 (2021).

-

Sindhu, O., Chandraprabha, M. N., Divyashri, G. & Murthy, T. K. Optimization of microwave-assisted pectin extraction from walnut shells and evaluation of its physicochemical and biological attributes. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 42, 101795. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scp.2024.101795 (2024).

-

Divyashri, G. et al. Valorization of coffee bean processing waste for the sustainable extraction of biologically active pectin. Heliyon https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e20212 (2023).

-

Hasanah, U., Setyowati, M., Edwarsyah, Efendi, R., Safitri, E., Idroes, R., Heng, L. Y., & Sani, N. D. Isolation of pectin from coffee pulp Arabica Gayo for the development of matrices membrane. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 523(1). https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/523/1/012014 (2019)

-

Rojas, R. et al. Mango peel as source of antioxidants and pectin: Microwave assisted extraction. Waste Biomass Valorization 6(6), 1095–1102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12649-015-9401-4 (2015).

-

Kamble, P. B., Gawande, S., & Patil, T. S. Extraction of pectin from unripe banana peel. International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology. www.irjet.net (2017)

-

Musita, N.- Characteristics of pectin extracted from cocoa pod husks. Pelita Perkebunan (a Coffee and Cocoa Research Journal), 37(1). https://doi.org/10.22302/iccri.jur.pelitaperkebunan.v37i1.428 (2021)

-

Zhang, W. et al. Effects of different extraction solvents on the compositions, primary structures, and anti-inflammatory activity of pectin from sweet potato processing by-products. Carbohyd. Polym. 347, 122766. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2024.122766 (2025).

-

Singh, R. P. & Tingirikari, J. M. R. Agro waste derived pectin poly and oligosaccharides: Synthesis and functional characterization. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 31, 101910. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcab.2021.101910 (2021).

-

Segar, H. M., Abd Gani, S., Khayat, M. E. & Rahim, M. B. H. A. Antioxidant and antidiabetic properties of pectin extracted from pomegranate (Punica granatum) Peel. J. Biochem. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 11(2), 35–40 (2023).

-

Zang, Y., Du, C., Ru, X., Cao, Y. & Zuo, F. Anti-diabetic effect of modified ‘Guanximiyou’pummelo peel pectin on type 2 diabetic mice via gut microbiota. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 242, 124865. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.124865 (2023).

-

Wikiera, A., Grabacka, M., Byczyński, Ł, Stodolak, B. & Mika, M. Enzymatically extracted apple pectin possesses antioxidant and antitumor activity. Molecules 26(5), 1434. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26051434 (2021).

-

Sabir, A., Ali Shahid Chatha, S., Mustafa Kamal, G., Bibi, S., Sohail, N., Alshammari, A., … & Chopra, H Extraction, chemical modification, and assessment of antioxidant potential of pectin from Pakistani Punica granatum peels. Sustainability, 16(23), 10454. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162310454 (2024)

-

Ávila, G., De Leonardis, D., Grilli, G., Lecchi, C. & Ceciliani, F. Anti-inflammatory activity of citrus pectin on chicken monocytes’ immune response. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 237, 110269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetimm.2021.110269 (2021).

-

Yabe, T. New understanding of pectin as a bioactive dietary fiber. Journal of Food Bioactives, 3, 95–100. https://doi.org/10.31665/JFB.2018.3152 (2018)

-

He, Y. et al. Effects of dietary fiber on human health. Food Sci. Human Wellness 11(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fshw.2021.07.001 (2022).

-

Yeung, Y. K., Kang, Y. R., So, B. R., Jung, S. K. & Chang, Y. H. Structural, antioxidant, prebiotic and anti-inflammatory properties of pectic oligosaccharides hydrolyzed from okra pectin by Fenton reaction. Food Hydrocolloids 118, 106779. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodhyd.2021.106779 (2021).

-

Blanco-Pérez, F. et al. The dietary fiber pectin: Health benefits and potential for the treatment of allergies by modulation of gut microbiota. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 21, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11882-021-01020-z (2021).

-

Beukema, M., Faas, M. M. & de Vos, P. The effects of different dietary fiber pectin structures on the gastrointestinal immune barrier: impact via gut microbiota and direct effects on immune cells. Exp. Mol. Med. 52(9), 1364–1376. https://doi.org/10.1038/s12276-020-0449-2 (2020).

-

Tang, X. & de Vos, P. Structure-function effects of different pectin chemistries and its impact on the gastrointestinal immune barrier system. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 1, 15 (2023).

-

Xiong, B. et al. Preparation, characterization, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of acid-soluble pectin from okra (Abelmoschus esculentus L.). Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 181, 824–834. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.03.202 (2021).

-

Zhang, Y. et al. Locally delivered modified citrus pectin-a galectin-3 inhibitor shows expected anti-inflammatory and unexpected regeneration-promoting effects on repair of articular cartilage defect. Biomaterials 291, 121870 (2022).

-

Dambuza, A. et al. Therapeutic potential of pectin and its derivatives in chronic diseases. Molecules 29(4), 896. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29040896 (2024).

-

Divyashri, G., Sadanandan, B., Chidambara Murthy, K. N., Shetty, K. & Mamta, K. Neuroprotective potential of non-digestible oligosaccharides: an overview of experimental evidence. Front. Pharmacol. 12, 712531. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2021.712531 (2021).

-

Guo, T. L., Navarro, J., Luna, M. I. & Xu, H. S. Dietary upplements and the gut– brain axis: A focus on lemon, glycerin, and their combinations. Dietetics 3(4), 463–482. https://doi.org/10.3390/dietetics3040034 (2024).

-

Li, M. et al. Pro-and anti-inflammatory effects of short chain fatty acids on immune and endothelial cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 831, 52–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2018.05.003 (2018).

-

Eslick, S., Thompson, C., Berthon, B. & Wood, L. Short-chain fatty acids as anti-inflammatory agents in overweight and obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr. Rev. 80(4), 838–856. https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuab059 (2022).

-

Sun, Y., Ho, C. T., Zhang, Y., Hong, M. & Zhang, X. Plant polysaccharides utilized by gut microbiota: new players in ameliorating cognitive impairment. J. Tradit. Complement. Med. 13(2), 128–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtcme.2022.01.003 (2023).

-

Wang, L. et al. Modified citrus pectin inhibits breast cancer development in mice by targeting tumor-associated macrophage survival and polarization in hypoxic microenvironment. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 43(6), 1556–1567. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41401-021-00748-8 (2022).

-

Morsy, S. A. A. et al. Doxycycline- loaded alcium phosphate nanoparticles with a pectin coat can ameliorate ipopolysaccharide- nduced neuroinflammation via enhancing AMPK. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 19(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11481-024-10099-w (2024).

-

Cui, Y., Zhang, N. N., Wang, D., Meng, W. H. & Chen, H. S. Modified citrus pectin alleviates cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury by inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome activation via TLR4/NF-ĸB signaling pathway in microglia. J. Inflamm. Res. 30, 3369–3385 (2022).

-

Alfarttoosi, K. H. & Rabeea, I. S. Cytotoxic evaluation of citrus pectin and paclitaxel, and assessment of the neuroprotection effect of citrus pectin on paclitaxel- induce peripheral neuropathy in human neuron cell ulture. Azerbaijan Pharm. Pharmacother. J. 23(2), 81–87 (2024).

-

Akgöl, J., Kutlay, Ö., Keskin Aktan, A. & Fırat, F. Assessment of modified citrus pectin’s effects on dementia in the scopolamine- induced alzheimer’s model in adult male Wistar rats. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 46(12), 13922–13936. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb46120832 (2024).

-

Nuzzo, D. et al. Protective, antioxidant and antiproliferative activity of grapefruit IntegroPectin on SH-SY5Y cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22(17), 9368 (2021).

-

Kaczmarska, A., Pieczywek, P. M., Cybulska, J. & Zdunek, A. Structure and functionality of rhamnogalacturonan I in the cell wall and in solution: A review. Carbohyd. Polym. 278, 118909. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2021.118909 (2022).

-

Sadanandan, B. et al. Aqueous spice extracts as alternative antimycotics to control highly drug resistant extensive biofilm forming clinical isolates of Candida albicans. PLoS One https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0281035 (2023).

-

Huang, C. et al. Anti-inflammatory activities of Guang-Pheretima extract in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated RAW 264.7 murine macrophages. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 18, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-018-2086-z (2018).

-

Woranam, K. et al. Anti-inflammatory activity of the dietary supplement Houttuynia cordata fermentation product in RAW264. 7 cells and Wistar rats. PloS One 15(3), e0230645 (2020).

-

Zhang, Y. et al. Involvement of Akt/mTOR in the neurotoxicity of rotenone-induced Parkinson’s disease models. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16(20), 3811. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16203811 (2019).

-

Spinei, M. & Oroian, M. Structural, functional and physicochemical properties of pectin from grape pomace as affected by different extraction techniques. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 224, 739–753. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.10.162 (2023).

-

Chandel, V. et al. Current advancements in pectin: extraction, properties and multifunctional applications. Foods 11(17), 2683. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11172683 (2022).

-

Singhal, S., Deka, S. C., Koidis, A. & Hulle, N. R. S. Standardization of extraction of pectin from Assam lemon (Citrus limon Burm f.) peels using novel technologies and quality characterization. Biomass Conv Biorefinery https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-024-05367-x (2024).

-

Karbuz, P. & Tugrul, N. Microwave and ultrasound assisted extraction of pectin from various fruits peel. J. Food Sci. Technol. 58(2), 641–650. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13197-020-04578-0 (2021).

-

Kumari, M., Singh, S. & Chauhan, A. K. A comparative study of the extraction of pectin from Kinnow (Citrus reticulata) peel using different techniques. Food Bioprocess Technol. 16(10), 2272–2286. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11947-023-03059-4 (2023).

-

Kong, Y. et al. Anti-inflammatory effect of a novel pectin polysaccharide from Rubus chingii Hu on colitis mice. Front. Nutr. 9, 868657. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2022.868657 (2022).

-

Taciak, B. et al. Evaluation of phenotypic and functional stability of RAW 264.7 cell line through serial passages. PloS One 13(6), e0198943 (2018).

-

Khabipov, A. et al. Raw 264.7 macrophage polarization by pancreatic cancer cells–a model for studying tumour-promoting macrophages. Anticancer Research 39(6), 2871–2882 (2019).

-

Wu, D. et al. Enzyme-extracted raspberry pectin exhibits a high-branched structure and enhanced anti-inflammatory properties than hot acid-extracted pectin. Food Chem. 383, 132387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.132387 (2022).

-

Chen, W., Zhu, X., Xin, X. & Zhang, M. Effect of the immunoregulation activity of a pectin polysaccharide from Saussurea laniceps petals on macrophage polarization. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 278, 134757. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.134757 (2024).

-

Zhu, M. et al. Structural characterization and immunological activity of pectin polysaccharide from kiwano (Cucumis metuliferus) peels. Carbohyd. Polym. 254, 117371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.117371 (2021).

-

Dong, L., Yin, L., Zhang, Y., Fu, X. & Lu, J. Anti-inflammatory effects of ononin on lipopolysaccharide-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells. Mol. Immunol. 83, 46–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molimm.2017.01.007 (2017).

-

Xiao, L., Ye, F., Zhou, Y. & Zhao, G. Utilization of pomelo peels to manufacture value-added products: A review. Food Chem. 351, 129247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.129247 (2021).

-

Kang, J. K., Chung, Y. C. & Hyun, C. G. Anti-inflammatory effects of 6-methylcoumarin in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages via regulation of MAPK and NF-κB signaling pathways. Molecules 26(17), 5351 (2021).

-

Insuan, O. et al. Anti-inflammatory effect of pineapple rhizome bromelain through downregulation of the NF-κB-and MAPKs-signaling pathways in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated RAW264. 7 cells. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 43(1), 93–106. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb43010008 (2021).

-

Vijay, A. et al. Supplementation with citrus low- methoxy pectin reduces levels of inflammation and anxiety in ealthy volunteers: A pilot controlled dietary intervention study. Nutrients 16(19), 3326 (2024).

-

Padoan, A., Musso, G., Contran, N. & Basso, D. Inflammation, autoinflammation and autoimmunity in inflammatory bowel diseases. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 45(7), 5534–5557. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16193326 (2023).

-

Scordino, M. et al. Anti-apoptotic and anti-inflammatory properties of grapefruit IntegroPectin on human microglial HMC3 cell line. Cells 13(4), 355. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells13040355 (2024).

-

Ma, J. X. et al. The hawthorn (Crataegus pinnatifida Bge.) fruit as a new dietary source of bioactive ingredients with multiple beneficial functions. Food Frontiers https://doi.org/10.1002/fft2.413 (2024).

-

Lopez-Suarez, L., Al Awabdh, S., Coumoul, X. & Chauvet, C. The SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cell line, a relevant in vitro cell model for investigating neurotoxicology in human: Focus on organic pollutants. Neurotoxicology 92, 131–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuro.2022.07.008 (2022).

-

Li, P. et al. Growth differentiation factor 15 protects SH-SY5Y cells from rotenone-induced toxicity by suppressing mitochondrial apoptosis. Front. Aging Neurosci. 14, 869558. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2022.869558 (2022).

-

Pakrashi, S., Chakraborty, J. & Bandyopadhyay, J. Neuroprotective role of quercetin on rotenone-induced toxicity in SH-SY5Y cell line through modulation of apoptotic and autophagic pathways. Neurochem. Res. 45(8), 1962–1973. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11064-020-03061-8 (2020).

-

Nuzzo, D., Picone, P., Giardina, C., Scordino, M., Mudò, G., Pagliaro, M., & Di Liberto, V (2021) Neuroprotective and mitoprotective effects of lemon integro pectin on SH-SY5Y cells. BioRxiv, 2021–02. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.09.430380

-

Chen, J. et al. Preparation, structural property, and antioxidant activities of a novel pectin polysaccharide from the flowers of Hibiscus syriacus Linn. Front. Nutr. 11, 1524846. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2024.1524846 (2025).

-

Vathsala, V. et al. Ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE) and characterization of citrus peel pectin: Comparison between pummelo (Citrus grandis L. Osbeck) and sweet lime (Citrus limetta Risso). Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 37, 101357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scp.2023.101357 (2024).

-

Mahmoud, M. H., Abu-Salem, F. M. & Azab, D. E. S. H. A comparative study of pectin green extraction methods from apple waste: Characterization and functional properties. Int. J. Food Sci. 2022(1), 2865921. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/2865921 (2022).

-

Sharifi, K. A. & Pirsa, S. Biodegradable film of black mulberry pulp pectin/chlorophyll of black mulberry leaf encapsulated with carboxymethylcellulose/silica nanoparticles: Investigation of physicochemical and antimicrobial properties. Mater. Chem. Phys. 267, 124580. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchemphys.2021.124580 (2021).

-

Talapphet, N. et al. Polysaccharide extracted from Taraxacum platycarpum root exerts immunomodulatory activity via MAPK and NF-κB pathways in RAW264. 7 cells. J. Ethnopharmacol. 281, 114519. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2021.114519 (2021).

-

Tabarsa, M., Jafari, A., You, S. & Cao, R. Immunostimulatory effects of a polysaccharide from Pimpinella anisum seeds on RAW264. 7 and NK-92 cells. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 213, 546–554. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.05.174 (2022).

-

Ciriminna, R. et al. Citrus IntegroPectin: a family of bioconjugates with large therapeuticn potential. ChemFoodChem 1(1), e00014. https://doi.org/10.1002/cfch.202500014 (2025).

-

Kedir, W. M., Deresa, E. M. & Diriba, T. F. Pharmaceutical and drug delivery applications of pectin and its modified nanocomposites. Heliyon https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e10654 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank the Principal and the Management, M S Ramaiah Institute of Technology for providing essential research facilities. Sindhu O thanks M S Ramaiah Institute of Technology for the invaluable support through the Ramaiah Doctoral Fellowship.

Funding

No funding was obtained for this study.

Ethics declarations

Competing of interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sindhu, O., Chandraprabha, M.N., Divyashri, G. et al. Evaluation of anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effect of walnut shell pectin. Sci Rep 15, 44583 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28340-8

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

Version of record:

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28340-8