Introduction

Aedes aegypti, the mosquito vector of dengue, Zika, yellow fever, and chikungunya viruses, is a continuing problem in the world today, causing diseases in millions of people every year1,2,3,4. With climate change expanding the geographical range of Ae. aegypti, and consequently the viruses it transmits5,6, along with the rise of insecticide resistance in this species7,8,9, novel control methods are urgently needed. Sterile Insect Technique, Wolbachia– and homing-based genetic biocontrol methods have made remarkable progress in Ae. aegypti within the past decade and are potential candidates for the control of Aedes mosquitoes10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17. However, the utility of each method depends highly on the preference of the communities where the modified mosquitoes could be released. This necessitates the development of a broad range of alternative strategies that communities and programme managers can select based on their specific requirements. While the aforementioned technologies can be modified to provide a wide range of persistence and/or invasiveness, an alternative class of local gene drive systems, which allow for the spread of a favourable genetic trait that can be highly persistent but also non-invasive, could be more desirable.

One example is the underdominance system. Underdominance, also known as negative heterosis, classically refers to situations where hybrids of two pure-breeding strains exhibit lower fitness than either parental type. This tends to result in frequency-dependent fitness effects, so that in mixed populations the rarer type is at a relative disadvantage as these will typically mate the more common type, producing lower-fitness hybrids. Designs for synthetic underdominance systems can be comprised of two paired toxin-antidote effectors18,19,20. Conceptually, this involves two distinct genetic elements, each carrying a toxin and a complementary antidote: one construct encodes toxin A paired with antidote B, while the second encodes toxin B paired with antidote A. Viability is thus maintained only in individuals possessing both genetic elements. Such systems, introduced into a wild-type population, exhibit an unstable equilibrium—at allele frequencies above this equilibrium the frequency of transgenic individuals tends to increase, as mating between transgene homozygotes and wild-type (WT) individuals leads to toxins and antidotes segregating, resulting in descendants with minimal or zero fitness, whereas mating among transgene homozygotes produces healthy offspring. Below the unstable equilibrium, the transgenes tend to decrease in frequency. Consequently, the wild-type population is gradually transformed into a modified population expressing a desired trait, such as refractoriness to pathogens, encoded alongside the transgene. Following establishment, a stable boundary between modified and unmodified populations emerges, as rare wild-type migrants into the transformed population suffer the frequency-dependent disadvantage characteristic of underdominance systems—and similarly for rare transgenic migrants into adjacent wild-type populations. This characteristic is particularly attractive from economic and regulatory perspectives, since once established, the transgenics persist for an extended period, yet remain spatially contained and non-invasive, minimising spread into neighboring populations. Another toxin-antidote system, Killer-Rescue, requires only a single toxin-antidote pair21,22. Killer-Rescue has different dynamics, being temporally and spatially limited; this system may be very useful for intermediate steps or limited field trials before full deployment.

Despite its promising characteristics, the development of synthetic underdominance systems in Ae. aegypti and other insect species have been hampered by the lack of a broadly applicable and effective toxin-antidote pair. Here, we explore the possibility of utilising in Ae. aegypti, the barnase-barstar (Bn-Bs) system, originally found in the bacterium Bacillus amyloliquefaciens, in particular for genetic biocontrol applications. In Bacillus amyloliquefaciens, Bn (110 amino acids) acts as an extracellular ribonuclease while Bs (89 amino acids) is a specific inhibitor that binds to Bn, neutralising the otherwise lethal effect of the ribonuclease activity 23. Due to the potent ribonuclease activity of Bn and the ability of Bs to repress it, the pair has been used to enforce outcrossing (heterosis) in a range of plants24,25,26,27. Here we show that the pair works similarly in Ae. aegypti cell culture (Aag2) and subsequently demonstrate that Bs can rescue the lethality of Bn in transgenic Ae. aegypti, as long as the expression of Bs overlaps with that of Bn. This adds a highly adaptable effector to the arsenal of genetic biocontrol of Ae. aegypti and potentially other insects.

Results

Bn is lethal in Aag2 cells and can be rescued with Bs

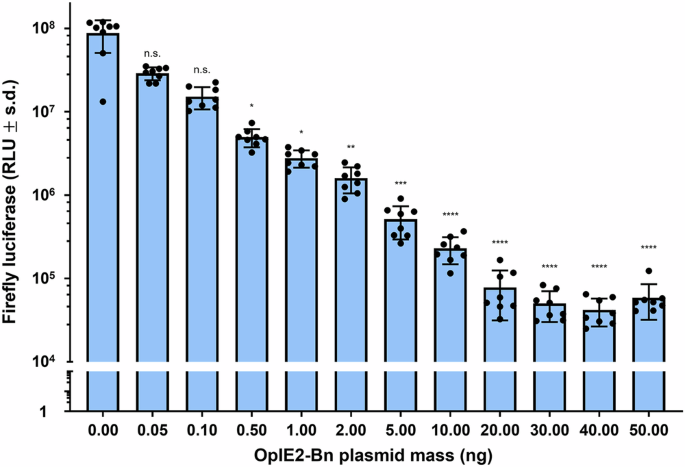

The killing effect of Bn was first assessed in vitro by transfecting Aag2 cells with a plasmid expressing PUb-Firefly luciferase (PUb-Fluc) as a proxy for cell viability and varying concentrations of a separate plasmid expressing Bn from the OpIE2 promoter. Fluc activity was found to decrease with increasing concentrations of Bn. It is conceivable that Bn, a ribonuclease, is specifically degrading Fluc RNA, but its broad specificity—cuts 5’ of G residues—and known ability to induce cell death in other systems, suggest that Bn induces cell death in the transfected cells (Fig. 1). Next, Aag2 cells were transfected with PUb-Fluc, 10 ng/well of OpIE2-Bn, and varying concentrations of a plasmid expressing Bs from the UbL40 promoter. Fluc activity was shown to gradually increase with increasing concentrations of UbL40-Bs compared to cells with neither OpIE2-Bn nor UbL40-Bs, indicating that the expression of Bs reverses the killing effect of Bn in Aag2 cells (Fig. 2).

Transfected cell viability is measured as a function of relative light units (RLU) produced by the luciferase assay. Mean values are indicated by the tip of each bar plot. Error bars are standard deviations. Statistical significance was estimated using Kruskal–Wallis test, followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison test relative to the RLU of cells treated with 0 ng of OpIE2-Bn plasmid (adjusted p values: p > 0.05 ns, p < 0.01**, p < 0.001***, p < 0.0001****).

Mean values are indicated by the tip of each bar plot. Error bars are standard deviations. Error bars are standard deviations. Statistical significance was estimated using Kruskal–Wallis test, followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison test relative to the RLU of cells treated with neither OpIE2-Bn nor UbL40-Bs plasmid (adjusted p values: p > 0.05 ns, p < 0.05*, p < 0.01**, p < 0.001***, p < 0.0001****).

Bn expression in vivo can affect a range of tissues in Ae. aegypti

Of the eight Ae. aegypti transgenic isolines expressing PUb-Bs-TRE-Bn established, two (G2 and W5) were selected for the assessments below based on genotype and sex ratio, indicating that both carried single transgene insertions and were not linked to the M/m loci associated with sex determination (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). These transgenics express Bs controlled by the polyubiquitin promoter (PUb-Bs) and Bn under the control of a tetracycline-responsive element (TRE-Bn). Bs is expressed autonomously, but Bn expression is only activated in the presence of a synthetic tetracycline-repressible transactivator (tTAV). After successfully separating the two elements using Cre (Supplementary Fig. 1), we crossed the two TRE-Bn isolines (hereafter named G2Bn and W5Bn to distinguish from the G2 and W5 isolines initially generated) to transgenic lines expressing tTAV ubiquitously (trunPUb-tTAV)28. Under Mendelian inheritance, each of the four potential progeny genotypes trunPUb-tTAV/TRE-Bn, trunPUb-tTAV, TRE-Bn, and non-transgenic should be present at equal frequency, i.e., 25%. However, upon screening the progeny, only 16.9% (χ 2, df.3, n = 295, p = 0.02) of larvae from isoline G2 carried both trunPUb-tTAV and TRE-Bn, while no such double heterozygotes (χ 2, df.3, n = 485, p < 0.0001) were found for isoline W5Bn, indicating that the trunPUb-tTAV-induced expression of TRE-Bn is fully lethal in the W5Bn isoline (Fig. 3). A decrease in viability in progeny inheriting only trunPUb-tTAV was also observed in crosses with W5Bn, but not with G2Bn (discussed further below). Since complete lethality was observed for isoline W5Bn, further experiments were carried out with this isoline.

Black dashed line indicates the expected proportion (25%) of each genotype if lethality is not observed. Note that the trunPUb promoter in trunPUb-tTAV has a reduced intron in the 5’UTR compared to the PUb promoter in PUb-Bs previously shown to reduce expression28.

We then crossed the W5Bn isoline to transgenic mosquitoes expressing tTAV in female indirect flight muscle (AeAct4-tTAV). As expected, targeting muscles essential for female flight resulted in a dramatic reduction in flight ability (Fisher’s exact test, n = 93, p < 0.0001) with no female AeAct4-tTAV/TRE-Bn transheterozygotes being able to fly (Fig. 4A, Supplementary Table 3). We also crossed the W5Bn isoline to transgenics expressing tTAV in the female midgut post bloodfeeding (AeCPA-tTAV). Female progeny with the four resulting genotypes were crossed to WT males and assessed for the number of eggs laid and the egg hatch rate. We did not find any statistically significant differences (Kruskal–Wallis test, n = 89, p > 0.67) in the number of eggs laid between WT and the three other genotypes (Supplementary Table 4) but egg hatch rates were reduced from an average of 70.7% in WT to 5.1% (Kruskal–Wallis test, n = 71, p < 0.0001) in transheterozygous females expressing Bn in the midgut (Fig. 4B, Supplementary Table 4).

A Percentage of females that were visibly flying in a cage 3–4 days post eclosion. Error bars are the Wilson 95% confidence intervals for the binomial proportion. Statistical significance was estimated using Fisher’s exact test (two-tailed) relative to the proportion of flying WT females (p > 0.05 ns, p < 0.0001****). B Percentage of eggs that successfully hatched 5 days after laying. Mean values are indicated by the tip of each bar plot. Error bars are standard deviations. Individual data points correspond to the hatch rate from each female. Statistical significance was estimated using Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison relative to the egg hatch rates from WT females (p > 0.05 ns, p < 0.0001****).

In the progeny of both crosses, genotype frequencies (Supplementary Table 3) did not deviate significantly from Mendelian expectations at the L4 larval stage (AeAct4-tTAV: χ 2, df.3, n = 538, p = 0.06; AeCPA-tTAV: χ 2, df.3, n = 1066, p = 0.81). Collectively, these findings demonstrate that tissue-specific fitness effects can be achieved through the use of tissue-specific regulatory elements to drive Bn expression.

Bs rescues mosquitoes from the effects of Bn

To assess the rescue ability of Bs, the initial PUb-Bs-TRE-BnW5 isoline was crossed to the trunPUb-tTAV line. The number of viable transheterozygous larvae screened from this cross was not significantly different from their non-transgenic siblings (χ2, df.3, n = 348, p = 0.18), demonstrating the rescue effect of Bs (Fig. 5A, Supplementary Table 5). Notably, progeny inheriting trunPUb-tTAV in this cross did not exhibit the reduced viability observed in Fig. 3A. We do not have any clear explanation for the apparent difference; however, this relates to a genotype with neither Bn nor Bs transgenes. High expression levels of tTAV are known to be deleterious29, however, this is unlikely to be the explanation here, as the trunPUb promoter used to drive tTAV expression was selected for its moderate, ubiquitous expression, shown in cell culture to have lower expression than the full-length promoter fragment28. Supporting this, no fitness effects were observed in Fig. 5A. In any case, while the tet-off system is very useful for testing components, as its binary nature and conditional (tetracycline-repressible) expression each facilitate the assembly of genetic systems comprising lethal genes, it is not necessary for applications such as Killer-Rescue or underdominance-based gene drives, in which the antidote element–here barstar–neutralises the lethal effect. If this configuration is ultimately employed as a component of an underdominance system, it will be essential to carefully evaluate the fitness costs associated with each transgene to enable accurate modelling of the system’s effectiveness.

A Percentage of viable larvae of different genotypes (n = 348). Black dashed line indicates the expected proportion (25%) of each genotype if lethality is not observed. B Percentage (n = 50) of female adults that were visibly flying in a cage 3–4 days post eclosion. Error bars are the Wilson 95% confidence intervals for the binomial proportion. Statistical significance was estimated using Fisher’s exact test (two-tailed) relative to the proportion of flying WT females (p > 0.05 ns, p < 0.0001****).

A partial rescue effect was observed in transheterozygotes for PUb-Bs-TRE-BnW5/AeAct4-tTAV; with 17/46 eclosed females (37%) observed to fly normally (Fig. 5B, Supplementary Table 6). Despite an improvement in flight ability, the transheterozygotes were still significantly worse than their WT siblings (Fisher’s exact test, n = 93, p < 0.0001), possibly due to expression of Bn and Bs from different promoters. Bs may not be expressed in female indirect flight muscles at a level high enough to fully rescue flight in all individuals. Since we observed incomplete rescue of AeAct4-Bn with PUb-Bs, we did not assess the latter’s ability to rescue the hatch rate of eggs produced by PUb-Bs-TRE-BnW5/AeCPA-tTAV.

Discussion

We have shown the Bn-Bs system from B. amyloliquefaciens to be functional in Ae. aegypti, to our knowledge, the first use in insects to date. We found that the inducible expression of Bn can cause lethality in mosquitoes and that the simultaneous expression of Bs can rescue this effect. PUb-Bs did not fully rescue the flightless phenotype caused by Bn expressed in indirect flight muscles (AeAct4-tTAV;TRE-BnW5), suggesting that the level of expression from PUb30 was insufficient in the indirect flight muscles, not surprising since AeAct429 is highly expressed in this tissue. We did, however, see a complete rescue of the lethal phenotype with PUb-Bs and trunPUb-tTAV;TRE-BnW5 expression. The trunPUb promoter has reduced expression compared to the full PUb promoter of PUb-Bs, so we would expect stronger, overlapping expression of Bs, which may be important for complete suppression. In order to translate this system into another organism, care should be taken in promoter selection, as for complete rescue, it is vital that Bs expression overlaps Bn in terms of expression pattern. Furthermore, our cell culture data further suggests that Bs expression levels should be greater than Bn. Coupling its effectiveness as a toxin-antidote with the very short coding sequences of both components, this system represents a use of this toxin-antidote pair that could easily be adapted for genetic control methods in mosquitoes, and potentially other insect species.

These results indicate that the pair could provide the basis for toxin/antidote-based gene drive systems. While Killer-Rescue requires a single toxin-antidote pair, most synthetic underdominance-based designs require two orthogonal pairs. However, this does not necessarily require two distinct toxins—and corresponding antidotes. The expansion of transgenesis in mosquitoes in recent years has led to the characterisation of an increased number and range of regulatory elements13,14,15,16,31. This could allow the development of an underdominance system using just one toxin-antidote pair if two distinct promoters with non-overlapping expression patterns are used. For example, one construct would have promoter A driving toxin expression and promoter B driving antidote expression, while the other construct would have promoter B driving toxin expression and promoter A driving antidote expression. As long as these two promoters do not overlap in their expression patterns, this arrangement could successfully create the conditions required for underdominance. Alternatively, Bn-Bs (as toxin-antidote A) could be combined with a second toxin-antidote system, such as CRISPR/Cas9 targeting an essential gene (toxin B) and its rescue sequence (antidote B)20, to form a functional underdominance system.

Methods

Plasmids and cloning

Plasmids AGG1829 (OpIE2-Bn)32, AGG1984 (UbL40-Bs-SV40)33,34, AGG1983 (UbL40-mCherry-SV40) were synthesised by Twist Bioscience. To generate AGG1767 (PUb-Bs-TRE-Bn), the PUb-Bs and Bn fragments were synthesised by Twist Bioscience. First PUb-Bs was cloned into the DraIII and AsiSI sites of AGG154635. Then the Bn fragment was cloned into the SpeI site of AGG1546+PUb-Bs. Complete plasmid sequences are available in NCBI: AGG1829 (PQ260750), AGG1894 (PQ260751), AGG1983 (PQ260747), AGG1767 (PQ260749), AGG1029 AeCPA-tTAV (PQ260745), AGG1506 AeAct4-tTAV (PQ260746), AGG1522 trunPub-tTAV (PQ260748).

Assessing Bn lethality in cells

Aag2 (Ae aegypti) cells were seeded at 5 × 104 cells/well in a 96-well plate. After 24 h the cells were transfected with 50 ng/well AGG1747 (PUb-Firefly luciferase)33, increasing concentrations of AGG1829 (OpIE2-Bn), and a DsRed expressing plasmid to maintain an equal total plasmid mass (100 ng) per well. Eight replicate wells were transfected using Transit-Pro (Mirius) for each condition according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Forty-eight hours later, the cells were washed once with phosphate-buffered saline and lysed in 50 µl 1× passive lysis buffer (Promega). A luciferase assay was performed with the Luciferase Assay Reagent II (Promega), using 3 µl of lysate and read on a GloMax according to the manufacturer’s instructions30.

Assessing the rescue ability of Bs in cells

Aag2 (Ae aegypti) cells (kind gift of R. Fragkoudis) were seeded at 5 × 104 cells/well in a 96-well plate. After 24 h, the cells were transfected with 50 ng/well AGG1747 (PUb-Firefly luciferase), 10 ng/well AGG1829 (OpIE2-Bn), increasing concentrations of AGG1984 (UbL40-Bs) and an mCherry expressing plasmid (AGG1983) to maintain an equal total plasmid mass (100 ng) per well. Eight replicate wells were transfected using Transit-Pro (Mirius) for each condition according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Forty-eight hours later, the cells were harvested in 1× passive lysis buffer (Promega), and a luciferase assay was performed with the Luciferase Assay Reagent II (Promega) and read on a GloMax Explorer as described above30.

Mosquito rearing

All experiments performed for this study were approved by the Biological Agents and Genetic Modification Safety Committee of The Pirbright Institute and undertaken in accordance with all relevant ethical regulations. Mosquitoes were reared at 28 +/−1 °C, 60–70% relative humidity on a 12/12 day-night/light cycle with 1 hour of dawn and dusk. Cages of adult mosquitoes were provided with 10% sucrose solution ad libitum, and females were bloodfed with defibrinated horse blood (TCS Bioscience) through a Hemotek membrane feeding system (Hemotek Ltd), with a parafilm (Merck) membrane. Females were allowed to lay eggs onto wet filter paper, and eggs were hatched in a vacuum chamber to degas the water and synchronise hatching. Early instar larvae were fed Liquifry (Interpet) and subsequently ground Tetramin flakes (Tetra). Liverpool13 served as the WT strain for crosses and microinjection.

Generation of transgenic lines

WT females were allowed to lay eggs in the dark for 35 min. Less than 1 h post-oviposition, eggs were collected, aligned on damp filter paper, transferred to double-sided tape (3 M) on a plastic cover-slip and injected as Jasinkiene et al.36. Injection mix comprised 500 ng/({{{rm{mu }}}})L of donor plasmid AGG1767 (PUb-Bs-TRE-Bn) and 300 ng/({{{rm{mu }}}})L of helper plasmid AGG1245 (PUb-hyperactive piggyBac transposase)13. Five days post-injection, G0 eggs were hatched in a vacuum chamber and reared as above. Adult G0 males were put into cages in groups of approximately 10 and crossed with WT females in a 1:5 ratio. Females were put into cages in groups of approximately 10 and crossed with WT males in a 1:1 ratio. Each cage was deemed a separate pool. Two days after crossing, the cages were bloodfed, and G1 eggs were collected from each pool. Eggs were hatched, and late larvae were screened for the presence of fluorescent markers. Transgenic larvae were reared to adulthood and crossed individually to WT to establish separate isolines. Males were crossed with WT females in a 1:5 ratio, and females with WT males in a 1:1 ratio. A total of 87 transgenic mosquitoes were generated from 8/12 pools of G₀ survivors (Supplementary File 1).

To establish separate PUb-Bs and TRE-Bn lines, male PUb-Bs-TRE-Bn from the established isolines were crossed to transgenic females expressing shu-Cre35. Males transheterozygous for PUb-Bs-TRE-Bn;shu-Cre were then crossed to WT, and the progeny were screened for separation of the fluorescent markers (Supplementary Table 1). Individuals that possessed only PUb-Bs (mCherry) or TRE-Bn (ZsYellow) markers were pool crossed to WT to establish separate PUb-Bs and TRE-Bn lines.

To activate the transcription of the Bn in the isolines above, we used previously validated ubiquitous (trunPUb-tTAV, AGG1522), female indirect flight muscle-specific (AeAct4-tTAV, AGG1506), and female midgut-specific (AeCPA-tTAV, AGG1029) tTAV-expressing transgenic isolines to activate Bn expression (P. Leftwich, personal communication).

Flight testing

50 female pupae of each genotype were placed into cages and allowed to eclose. Three to four days post eclosion, flight ability was assessed through observation. Flight was encouraged by tapping the area of the cage where the mosquito rested, as Navarro et al.37. Flying adults were removed from the cage, and non-flyers were reassessed for flight ability using the same method one to two days later to confirm their status.

Fertility testing

Approximately four days post eclosion, 50 females of each of the four genotypes were crossed in cages with 25 WT males. Six days later, females were allowed to blood feed for four hours, and non-bloodfed females were removed from the cage one day later. Three days after blood feeding, females were transferred into modified 24-well tissue culture plates containing 2% agarose (EAgaL plates), and the fertility assay was carried out as Tsujimoto and Adelman38, but without the use of image analysis software. Females were allowed to lay eggs in the plates for ~24 h, then were returned to the cage so the assay could be repeated through the second oviposition. Eggs were counted under a dissecting microscope, then vacuum hatched five days after they were laid. One to two days after hatching, L1 larvae were chilled on ice to immobilise them and were counted under a dissecting microscope.

Statistics and reproducibility

The exact number of mosquitoes and repetitions for each experiment are indicated in the Supplementary Data File 1, Figures and/or the Figure legends. Data analysis and graph production were done using GraphPad Prism 10.

For comparisons between control and multiple treatment groups involving continuous, non-normally distributed data (Figs. 1, 2, and 4B), statistical significance was assessed using the Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s post-hoc multiple comparison test. To control the false discovery rate, the Benjamini, Krieger, and Yekutieli two-stage linear step-up procedure was applied to the resulting p values.

For categorical data (Figs. 3, 4A, and 5), statistical significance between control and treatment groups was evaluated using Fisher’s exact test (two-tailed). Chi-square tests were employed to determine significant deviations from expected Mendelian inheritance ratios.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data generated for this study are available in the main manuscript and supplementary files. Full plasmid sequences are publicly available from NCBI accession numbers: PQ260745-PQ260751. Plasmids are available through Addgene numbers: 242438-242441.

References

-

Dengue and severe dengue. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dengue-and-severe-dengue (2024).

-

Chikungunya fact sheet. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/chikungunya (2025).

-

Zika virus. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/zika-virus (2022).

-

Yellow fever. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/yellow-fever (2023).

-

The 2023 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: the imperative for a health-centred response in a world facing irreversible harms. Lancet 402, p2346–2394 (2023).

-

Bhatt, S. et al. The global distribution and burden of dengue. Nature 496, 504–507 (2013).

-

Wang, Y. et al. Insecticide resistance: Status and potential mechanisms in Aedes aegypti. Pestic Biochem. Physiol. 195, 105577 (2023).

-

Sene, N. M. et al. Insecticide resistance status and mechanisms in Aedes aegypti populations from Senegal. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 15, e0009393 (2021).

-

Konkon, A. K. et al. Insecticide resistance status of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes in southern Benin, West Africa. Trop. Med. Health 51, 22 (2023).

-

Velez, I. D. et al. Reduced dengue incidence following city-wide wMel Wolbachia mosquito releases throughout three Colombian cities: Interrupted time series analysis and a prospective case-control study. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 17, e0011713 (2023).

-

Spinner, S. A. M. et al. New self-sexing Aedes aegypti strain eliminates barriers to scalable and sustainable vector control for governments and communities in dengue-prone environments. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 10, 975786 (2022).

-

Lim, J. T. et al. Efficacy of Wolbachia-mediated sterility to reduce the incidence of dengue: a synthetic control study in Singapore. Lancet Microbe 5, e422–e432 (2024).

-

Anderson, M. A. E. et al. Closing the gap to effective gene drive in Aedes aegypti by exploiting germline regulatory elements. Nat. Commun. 14, 338 (2023).

-

Li, M. et al. Development of a confinable gene drive system in the human disease vector Aedes aegypti. eLife 9, e51701 (2020).

-

Verkuijl, S. A. N. et al. A CRISPR endonuclease gene drive reveals distinct mechanisms of inheritance bias. Nat. Commun. 13, 7145 (2022).

-

Reid, W. et al. Assessing single-locus CRISPR/Cas9-based gene drive variants in the mosquito Aedes aegypti via single-generation crosses and modeling. G3 12, jkac280 (2022).

-

Anderson, M. A. E. et al. A multiplexed, confinable CRISPR/Cas9 gene drive can propagate in caged Aedes aegypti populations. Nat. Commun. 15, 729 (2024).

-

Davis, S., Bax, N. & Grewe, P. Engineered Underdominance Allows Efficient and Economical Introgression of Traits into Pest Populations. J. Theor. Biol. 212, 83–98 (2001).

-

Edgington, M. P. & Alphey, L. S. Population dynamics of engineered underdominance and killer-rescue gene drives in the control of disease vectors. PLOS Comput. Biol. 14, e1006059 (2018).

-

Champer, J., Champer, S. E., Kim, I. K., Clark, A. G. & Messer, P. W. Design and analysis of CRISPR-based underdominance toxin-antidote gene drives. Evol. Appl. 14, 1052–1069 (2021).

-

Gould, F., Huang, Y., Legros, M. & Lloyd, A. L. A Killer–Rescue system for self-limiting gene drive of anti-pathogen constructs. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 275, 2823–2829 (2008).

-

Edgington, M. P., Harvey-Samuel, T. & Alphey, L. Split drive killer-rescue provides a novel threshold-dependent gene drive. Sci. Rep. 10, 20520 (2020).

-

Hartley, R. W. Barnase and barstar: two small proteins to fold and fit together. Trends Biochem. Sci. 14, 450–454 (1989).

-

Szeluga, N., Baldrich, P., DelPercio, R., Meyers, B. C. & Frank, M. H. Introduction of barnase/barstar in soybean produces a rescuable male sterility system for hybrid breeding. Plant Biotechnol. J. 21, 2585–2596 (2023).

-

Mariani, C., Beuckeleer, M. D., Truettner, J., Leemans, J. & Goldberg, R. B. Induction of male sterility in plants by a chimaeric ribonuclease gene. Nature 347, 737–741 (1990).

-

Mariani, C. et al. A chimaeric ribonuclease-inhibitor gene restores fertility to male sterile plants. Nature 357, 384–387 (1992).

-

Colombo, N. & Galmarini, C. R. The use of genetic, manual and chemical methods to control pollination in vegetable hybrid seed production: a review. Plant Breed. 136, 287–299 (2017).

-

Leftwich, P. T. et al. A synthetic biology approach to transgene expression in insects. ACS Synth. Biol. 13, 3041–3045 (2024).

-

Fu, G. et al. Female-specific flightless phenotype for mosquito control. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 107, 4550–4554 (2010).

-

Anderson, M. A. E. et al. AePUb promoter length modulates gene expression in Aedes aegypti. Sci. Rep. 13, 20352 (2023).

-

Gantz, V. M. et al. Highly efficient Cas9-mediated gene drive for population modification of the malaria vector mosquito Anopheles stephensi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 112, E6736–E6743 (2015).

-

Okorokov, A. L., Hartley, R. W. & Panov, K. I. An improved system for ribonuclease Ba expression. Protein Expr. Purif. 5, 547–552 (1994).

-

Anderson, M.aE., Gross, T. L., Myles, K. M. & Adelman, Z. N. Validation of novel promoter sequences derived from two endogenous ubiquitin genes in transgenic Aedes aegypti. Insect Mol. Biol. 19, 441–449 (2010).

-

Hartley, R. W. Directed mutagenesis and barnase-barstar recognition. Biochemistry 32, 5978–5984 (1993).

-

Carabajal Paladino, L. Z. et al. Optimizing CRE and PhiC31 mediated recombination in Aedes aegypti. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 11, 1254863 (2023).

-

Jasinskiene, N., Juhn, J. & James, A. A. Microinjection of A. aegypti embryos to obtain transgenic mosquitoes. J. Vis. Exp. e219 (2007).

-

Navarro-Payá, D. et al. Targeting female flight for genetic control of mosquitoes. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 14, e0008876 (2020).

-

Tsujimoto, H. & Adelman, Z. N. Improved fecundity and fertility assay for Aedes aegypti using 24 well tissue culture plates (EAgaL Plates). J. Vis. Exp. 4, e61232 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the UK Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council [BBS/E/I/00007033, BBS/E/I/00007038, and BBS/E/I/00007039] strategic funding to The Pirbright Institute.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

L.A. declares the following competing interests: L.A. is an adviser to Synvect Inc. and Biocentis Ltd, with equity and/or financial interest in those companies. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Elerson Rocha and the other, anonymous, reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Tobias Goris.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nevard, K., Ang, J.X.D., Anderson, M.A.E. et al. Harnessing the highly adaptable barnase-barstar system for genetic biocontrol of Aedes aegypti. Commun Biol 8, 1154 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08588-6

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08588-6