References

-

WHO. Indian Priority Pathogen List. 1–24 (2021).

-

Diniz-lima, I. et al. Cryptococcus : History, epidemiology and immune evasion. Appl. Sci. 12(14), 7086 (2022).

-

Rajasingham, R. et al. Articles The global burden of HIV-associated cryptococcal infection in adults in 2020: A modelling analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 3099, 1–8 (2022).

-

Coelho, C., Bocca, A. L. & Casadevall, A. The tools for virulence of cryptococcus neoformans. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 87, 1–41 (2014).

-

Firacative, C., Meyer, W. & Castañeda, E. Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii species complexes in Latin America: A map of molecular types, genotypic diversity, and antifungal susceptibility as reported by the Latin American cryptococcal study group. J. Fungi 7, 282 (2021).

-

Maziarz, E. K. & Perfect, J. R. Cryptococcosis. Infect. Dis. Clin. North Am. 30, 179–206 (2016).

-

Rathore, S. S., Sathiyamoorthy, J., Lalitha, C. & Ramakrishnan, J. A holistic review on Cryptococcus neoformans. Microb. Pathog. 166, 105521 (2022).

-

Vu, K. et al. Invasion of the central nervous system by Cryptococcus neoformans requires a secreted fungal metalloprotease. MBio 5, 1–13 (2014).

-

Kwon-chung, K. J. et al. Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii, the etiologic agents of Cryptococcosis. Cold Spring Harb. Prespectives Med. 4, a019760 (2014).

-

Xess, I. et al. Multilocus Sequence typing of clinical isolates of Cryptococcus from India. Mycopathologia 186, 199–211 (2021).

-

Chayakulkeeree, M. & Perfect, J. R. Cryptococcosis. Infect. Dis. Clin. North Am. 20, 507–544 (2006).

-

Sabiiti, W. & May, R. C. Mechanisms of infection by the human fungal pathogen. Future Microbiol. 7, 1297–1313 (2012).

-

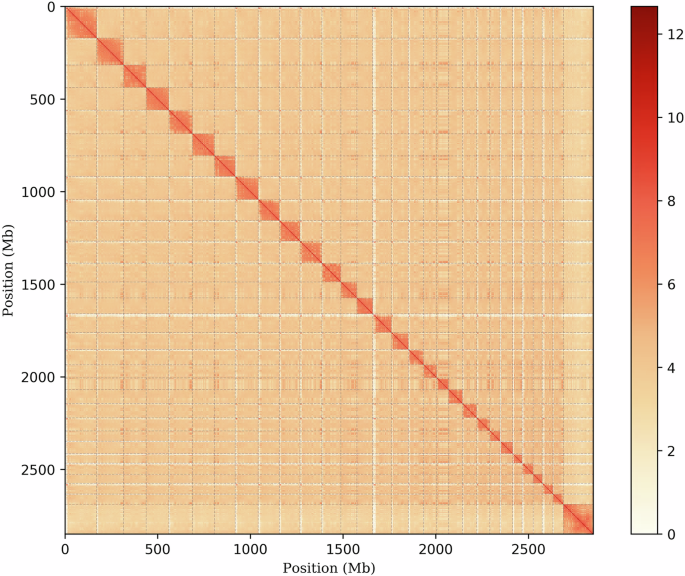

Patiño, L. H. et al. A landscape of the genomic structure of Cryptococcus neoformans in Colombian isolates. J. Fungi 9, 135 (2023).

-

Arastehfar, A. et al. Drug-resistant fungi: An emerging challenge threatening our limited antifungal armamentarium. Antibiotics 9, 1–29 (2020).

-

Brown, S. M., Campbell, L. T. & Lodge, J. K. Cryptococcus neoformans, a fungus under stress. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 10, 320–325 (2007).

-

Ding, H. et al. ATG genes influence the virulence of Cryptococcus neoformans through contributions beyond core autophagy functions. Infect. Immun. 86, 1–24 (2018).

-

Zhao, X. et al. Conserved autophagy pathway contributes to stress tolerance and virulence and differentially controls autophagic flux upon nutrient starvation in Cryptococcus neoformans. Front. Microbiol. 10, 1–14 (2019).

-

Jiang, S. T. et al. Autophagy regulates fungal virulence and sexual reproduction in Cryptococcus neoformans. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 8, 374 (2020).

-

Park, Y. D. et al. Identification of multiple cryptococcal fungicidal drug targets by combined gene dosing and drug affinity responsive target stability screening. MBio 7, 1–12 (2016).

-

Cao, C., Wang, Y., Husain, S., Soteropoulos, P. & Xue, C. Echinocandin Resistance in Cryptococcus neoformans. 1–18 (2019).

-

Gow, N. A. R. et al. The importance of antimicrobial resistance in medical mycology. Nat. Commun. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-32249-5 (2022).

-

Alastruey-Izquierdo, A. & Martín-Galiano, A. J. The challenges of the genome-based identification of antifungal resistance in the clinical routine. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1–8 (2023).

-

Wu, S. et al. Progress of polymer-based strategies in fungal disease management: Designed for different roles. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 13, 1–26 (2023).

-

Tan, K. L. S. & Mohamad, S. B. Fungal pathogen in digital age: Review on current state and trend of comparative genomics studies of pathogenic fungi. Adv. Microbiol. 63, 23–31 (2024).

-

Rathore, S. S., Raman, T. & Ramakrishnan, J. Magnesium Ion acts as a signal for capsule induction in Cryptococcus neoformans. Front. Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2016.00325 (2017).

-

Rathore, S. S., Isravel, M., Vellaisamy, S. & Raj, D. Exploration of antifungal and immunomodulatory potentials of a furanone derivative to rescue disseminated Cryptococosis in mice. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-15500-8 (2017).

-

Cuomo, C., & Litvintseva, P. (2014). Population genomic analysis of the human pathogenic fungus Cryptococcus neoformans. Mycoses, 57(Suppl. 1), 17.

-

Hagen, F. et al. Recognition of seven species in the Cryptococcus gattii/Cryptococcus neoformans species complex. Fungal Genet. Biol. 78, 16–48 (2015).

-

Caza, M. & Kronstad, J. W. The cAMP/protein kinase a pathway regulates virulence and adaptation to host conditions in Cryptococcus neoformans. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 9, 1–15 (2019).

-

Bürgel, P. H. et al. Cryptococcus neoformans secretes small molecules that inhibit IL-1 β inflammasome-dependent secretion. Mediat. Inflamm. 2020, 3412763 (2020).

-

Bolano, A. et al. Rapid methods to extract DNA and RNA from Cryptococcus neoformans. FEMS Yeast Res. 1, 221–224 (2001).

-

Watanabe, M. et al. Rapid and effective DNA extraction method with bead grinding for a large amount of fungal DNA. J. Food Prot. 73, 1077–1084 (2010).

-

QIAseq ® FX DNA Library Kit Handbook. (2023).

-

Zimin, A. V. et al. The MaSuRCA genome assembler. Bioinformatics 29, 2669–2677 (2013).

-

Xu, G., Xu, T., Zhu, R., Wang, H. & Li, J. LR Gapcloser : a tiling path-based gap closer that uses long reads to complete genome assembly. 1–14 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1093/gigascience/giy157

-

Manni, M., Berkeley, M. R., Seppey, M. & Zdobnov, E. M. BUSCO : Assessing Genomic Data Quality and Beyond. 1–41 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1002/cpz1.323

-

Hoff, K. J., Lomsadze, A., Stanke, M. & Borodovsky, M. BRAKER2 : automatic eukaryotic genome annotation with GeneMark-EP + and AUGUSTUS supported by a ´ s ˇ Br una Tom a. 3, 1–11 (2021).

-

Buchfink, B., Xie, C. & Huson, D. H. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. 12, (2015).

-

Moriya, Y., Itoh, M., Okuda, S., Yoshizawa, A. C. & Kanehisa, M. KAAS: an automatic genome annotation and pathway reconstruction server. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, 182–185 (2007).

-

Stanke, M. & Morgenstern, B. AUGUSTUS: a web server for gene prediction in eukaryotes that allows user-defined constraints. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, 465–467 (2005).

-

Mau, B. & Perna, N. T. Progressive Mauve : Multiple alignment of genomes with gene flux and rearrangement. (2014). Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/0910.5780

-

Ha, S. Y. S., Lim, J., Kwon, S. & Chun, J. A large-scale evaluation of algorithms to calculate average nucleotide identity. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 110, 1281–1286 (2017).

-

Community, T. G. The Galaxy platform for accessible , reproducible , and collabor ativ e data analyses : 2024 update. Nucleic acids research 52, no. W1 (2024): W83-W94(2024).

-

Kumar, S., Stecher, G., Li, M., Knyaz, C. & Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 35, 1547–1549 (2018).

-

Letunic, I. & Bork, P. Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v6: recent updates to the phylogenetic tree display and annotation tool. Nucleic Acids Res. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkae268 (2024).

-

Zhang, S. et al. The Hsp70 member, Ssa1, acts as a DNA-binding transcriptional co-activator of laccase in Cryptococcus neoformans. Mol. Microbiol. 62, 1090–1101 (2006).

-

Lu, T., Yao, B. & Zhang, C. Original article DFVF : Database of fungal virulence factors. Database 2012, 1–4 (2012).

-

Almeida FWolf JM, Casadevall A2015.Virulence-Associated Enzymes of Cryptococcus neoformans. Eukaryot Cell14:.https://doi.org/10.1128/ec.00103-15

-

Azevedo, R., Rizzo, J. & Rodrigues, M. Virulence Factors as targets for anticryptococcal therapy. J. Fungi 2, 29 (2016).

-

Malachowski, A. N. et al. Systemic approach to virulence gene network analysis for gaining new insight into cryptococcal virulence. Front. Microbiol. 7, 1–14 (2016).

-

Brandão, F. et al. HDAC genes play distinct and redundant roles in Cryptococcus neoformans virulence. Sci. Rep. 8, 1–17 (2018).

-

Verma, S., Shakya, V. P. S. & Idnurm, A. Exploring and exploiting the connection between mitochondria and the virulence of human pathogenic fungi. Virulence 9, 426–446 (2018).

-

Zaragoza, O. Basic principles of the virulence of Cryptococcus. Virulence 10, 490–501 (2019).

-

Sun, J. et al. OrthoVenn3: An integrated platform for exploring and visualizing orthologous data across genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, W397–W403 (2023).