Introduction: mucosal inflammation

Engineering immunomodulatory biomaterials for chronic inflammation at mucosal tissue sites relies on overcoming both fundamental challenges associated with mucosal barrier function and the unique immune microenvironment of mucosae during inflammatory processes. Given the expansiveness of this field and its accelerating progress, we will focus on two select tissues, the lungs and the gastrointestinal tract, and we will not seek to provide a comprehensive cataloging of all recent research. Rather, we will highlight selected vignettes from the past few years that demonstrate specific evolving concepts. First, a brief section will orient the reader to the main biological processes that are sought to be controlled and regulated; following this, select examples of recent progress in this dynamic research area will be highlighted. More comprehensive discussions of mucosal biomaterial vaccines can be found in other recent reviews1,2.

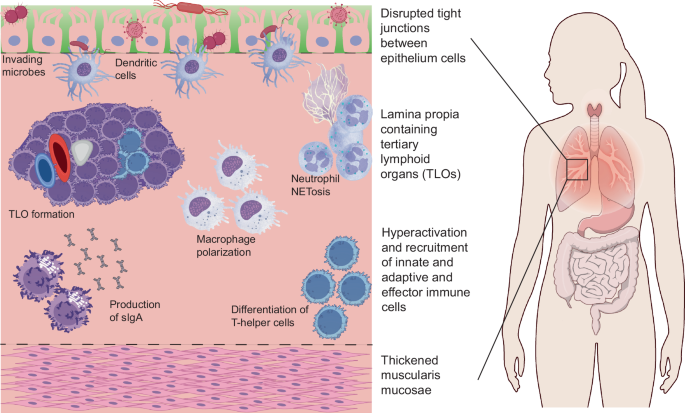

Inflammation after tissue injury is a multifactorial process with a reparative timeline following three distinct stages associated with the activity of specific immune cell subsets. Although different inflammatory diseases associated with mucosal tissues have unique pathologies, they also share generalities (Fig. 1). In the early pro-inflammatory stage, an initial response is commonly mounted in response to damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) or pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) from damaged cells or pathogens, respectively. For example, resident immune cells, including neutrophils and tissue-specific macrophages, are commonly activated and release inflammatory mediators that recruit CD4 + T helper1 (TH1) cells and circulating monocytes to aid in pathogen clearance and angiogenesis. In the second stage, as the inflammatory cytokine milieu begins to subside, a reparative phenotype is commonly induced with the recruitment of regulatory T (Treg) cells, TH2 cells, and M2-like macrophages responsible for producing pro-regenerative cytokines, including TGF-β and IL-103,4.

The final resolution stage involves an active host response to restore tissue integrity. The clearance of pro-inflammatory mediators results in an overall decline in the number of infiltrating immune cells at the tissue injury site, which in turn prompts pro-regenerative cells to restore homeostatic tissue conditions5,6. Dysregulation of this overall repair timeline results in an extended chronic inflammatory state, which contributes to deterioration of immune tolerance, tissue injury, or a fibrotic pathology7,8,9.

At mucosal tissue sites, the progression of chronic inflammation is further characterized by additional processes that reflect pathological changes to its unique tissue architecture (Fig. 1). Mucosal tissues line various body cavities and organs exposed to the external environment and include the oral cavity, respiratory, gastrointestinal, and genitourinary tracts. The mucosa consists of three layers, including an epithelial surface layer consisting of either simple columnar or stratified squamous cells, an underlying lamina propria containing specialized mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT), and a deeper layer of smooth muscle. Goblet cells in the epithelial layer secrete mucus, which traps foreign particles and pathogens, preventing their entry into deeper tissues10. In studies with Muc2-deficient mice unable to secrete a functional mucus layer, gut dysbiosis triggered the early onset and perpetuation of colitis as invading pathogens could more easily proliferate, breach the epithelial layer, and recruit local lymphocytes11.

Apart from the universal features of chronic inflammation apparent across all tissue types, including the hyperactivation of a certain population of innate and adaptive immune cells, the mucosal tissue sites have their own set of characteristic features, including increased permeability of the epithelium resulting in increased microbe penetration and the formation of pathologic tertiary lymphoid structures within the lamina propria.

In addition to this protective mucus layer, mucosal tissue responses following an insult are unique because of the immune properties inherent to their epithelial cells. Some gut-specific specialized immune cells include goblet cells containing “antigen passages” which traffic antigens in the lumen to dendritic cells in the underlying lamina propria12, intestinal epithelial cells capable of phagocytosis of commensal fungi13, and tuft cells which secrete IL-25 in response to parasitic infection14. When both cellular barriers and the immune response of these specialized cells fail, microbial dysbiosis can be yet another initiator of chronic inflammation. For example, in a study where the microbiota from inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients were transplanted into germ-free mice, naïve T cells were differentiated towards a TH17 state, resulting in the perpetuation of colitis pathology15. Furthermore, TH1-mediated inflammation following intestinal colonization by specific strains of pathogenic bacteria has also been demonstrated to also induce IBD in genetically-susceptible mice models16,17.

Regardless of the type of insult, one of the most obvious tissue architecture changes that is a hallmark of unresolved chronic inflammation is the development of tertiary lymphoid organs (TLOs) at the mucosal tissue sites. Mature TLOs are ectopic lymphocyte clusters that share similarities with secondary lymphoid organs as they contain organized T-cell zones, B-cell follicles, and high endothelial venules18. The formation of TLOs is primarily driven by cytokine-mediated activation of resident stromal cells, such as fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and smooth muscle cells. These activated cells produce homeostatic lymphoid chemokines that recruit and retain leukocytes at the site of inflammation. Depending on the disease context and timeline, TLOs can either benefit or burden disease resolution. For example, in the case of TH2-mediated acute allergic inflammation, it was observed in mice that the presence of iBALT did not worsen allergic responses to repeated pulmonary allergen exposure. Instead, these mice had reduced TH2 cytokine mRNA expression, eosinophil recruitment, and mucus production. The authors of this study hypothesize that the iBALT structures created a local concentration of immune cells that were responsible for sequestering effector T cells and antigens in a manner that minimizes widespread tissue inflammation19. Whereas TLOs in these acute conditions regress with the return to tissue homeostasis, in chronic inflammatory diseases, extended exposure to stimuli leads to continued recruitment and activation of immune cells, including dendritic cells and follicular helper T cells, responsible for promoting B cell activity and structural maturation of TLOs. For example, in studies conducted with lung samples derived from patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), iBALT formation correlated with disease severity as elevated levels of chemokines CXCL12, CXCL13, and cholesterol metabolites facilitated CD4 + T cells secretion of the cytokines IL-6, IL-1β, and TGF-β and the polarization into T-follicular helper cells by type 2 dendritic cells20. The authors of this study suggest that the persistence of these immune cell subsets in the context of this disease results in a self-amplifying positive feedback loop that promotes the persistence of the iBALT structure and exacerbations of the chronic inflammatory state20. In more severe cases, TLOs even induce tissue damage as exemplified in lung biopsies of rheumatoid arthritis patients with pulmonary complications. Trichrome and α-SMA+ staining of these biopsies revealed collagen deposition near iBALT germinal centers, suggesting a pathological consequence of such dysregulated local immune activity21. Considering the dynamic role TLOs play in disease resolution, targeting key cellular or chemokine drivers of these ectopic structures offers a unique therapeutic target to either engage or curtail this localized immune machinery, depending on the type and exposure of a given insult.

Another distinguishing feature of mucosal tissue sites is the active downregulation of immune responses to innocuous antigens, as is the case with certain airborne particulates in the respiratory tract and food antigens or commensal bacteria in the digestive tract. In healthy physiologic states, the preferential immune-tolerant state is maintained by both the innate and adaptive immune system, with the existence of tolerance-inducing innate effector cells such as dendritic cells and the broadly neutralizing activity of mucosal secretory IgA antibodies, respectively. For example, in the mesenteric lymph nodes, specialized CD103+ dendritic cells exposed to innocuous oral antigens produce retinoic acid, which, in synergy with TGF-β, supports the differentiation of naïve T cells into Foxp3+ Treg cells, helping to establish local immune tolerance in the gut22. Furthermore, in a seminal study conducted by Murai and collaborators, the role of IL-10 secretion by local CD11b + CD11c+ dendritic cells in the gut was also elucidated as pivotal in maintaining Foxp3 expression of Tregs in the context of colitis prevention23. Following an insult, mucosa-specific Tregs have also been shown to play an essential role in maintaining homeostasis by preventing hyperactivity of a type 2 immune response24,25,27. In a study conducted with mice deficient in peripheral Tregs, it was demonstrated that a loss of this cell population resulted in upregulation of IL-4 and IL-13, loss of commensal bacteria, and intestinal epithelial pathology, including colonic crypt hyperplasia upon microbial exposure24.

In the most severe cases, mucosal tissue sites that enter this state of type-2 specific immune dysregulation experience an excessive accumulation of extracellular matrix (ECM) components deposited by myofibroblasts, resulting in tissue fibrosis26,27. In vivo studies with lung fibroblast samples from idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) patients revealed that IL-13 significantly promotes the expression of α-SMA and collagen I by upregulating the expression of TGF-β, in contrast to fibroblasts derived from healthy patients28. Furthermore, oxidative stress prompted by recruited innate immune cells and local pulmonary fibroblasts further contributes to fibroblast activation through the activity of NADPH oxidase (NOX) derived reactive oxygen species (ROS). Studies have demonstrated that by engaging in a positive feedback loop with TGF-β, ROS concentrations in the tissue amplify further, promoting cytokine-induced fibroblast-myofibroblast transition and fibrosis29. The imbalance between the new ECM production by these activated fibroblasts and degradation by matrix metalloprotease enzymes results in increased matrix stiffness and scar tissue formation, compromising normal tissue architecture and function30.

The design of immunomodulatory biomaterials to treat chronic inflammation at these mucosal sites must strike a fine balance between promoting therapeutic activity by polarizing immune cells towards a more regulated response while simultaneously minimizing any detrimental interactions between the biomaterial itself and the mucosal barrier. While there are other reviews that discuss the role of biomaterials to treat chronic inflammation broadly9,31,32,33, this perspective piece will particularly highlight novel biomaterial designs that address these challenges in two central mucosal tissue sites in the body: the respiratory and digestive tracts.

Biomaterials for treating chronic inflammation in the respiratory tract

The respiratory tract can be divided into two main zones, including the conducting and respiratory zones centered around the lungs. The conducting zone is lined with a mucous layer and spans from the nose to the trachea and is responsible for the transfer of air to and from the lungs. The respiratory zone includes the primary bronchi, bronchioles, terminal bronchioles, alveolar ducts, and alveoli, where gas exchange can occur with adjacent blood capillaries. Besides pneumocytes that have a specialized role in gas exchange, the lungs contain other functional cell types that play pivotal roles in responding to infection and inflammation. In the respiratory zone, tissue resident immune cells are scattered throughout the airspace and are poised to mount a host defense response against a given insult34,35. This includes alveolar and interstitial macrophages, dendritic cells, natural killer cells, and innate lymphoid cells that make up the innate arm of the immune response and activated antigen-specific T and B cells that make up the adaptive immune response36. Treating chronic inflammation in the respiratory tract relies on accessing and engaging this wide array of immune populations.

Macrophage polarization to modulate immune-stromal crosstalk

One of the key innate immune cell types that can drive the fibrotic state are macrophages. Although at one time distinguished as either “classically” activated M1 macrophages or “alternatively activated” M2 macrophages, recent advancements in single-cell RNA sequencing have demonstrated the plasticity of this cell type in phenotypic expression in response to environmental cues37,38. With this in mind, macrophage heterogeneity can be better described as existing on a spectrum or a “multidimensional network of states,” where factors including tissue context, stimuli, and function can correlate back to cell marker expression38. This understanding of macrophage heterogeneity helps biomaterial researchers identify disease-specific macrophage phenotypes for targeting, and it recognizes that the function of macrophages is highly dependent on the state of the tissues in which they persist.

In the lungs, tissue-resident alveolar and interstitial macrophages are responsible for maintaining tissue homeostasis, but in chronic inflammatory conditions such as IPF, monocyte-derived alveolar macrophages (Mo-AMs) upregulate the secretion of pro-fibrotic cytokines, resulting in aberrant fibroblast proliferation and ECM deposition. Recent studies have demonstrated that there exists an “immune-stromal” crosstalk that further accelerates the transition from favorable acute repair to destructive chronic fibrosis39,40. Work done by Hinz and collaborators has elucidated key adhesion protein interactions via cadherin-11 that facilitate specific macrophage-fibroblast binding interaction, which prompts TGF-β activity and consequently differentiation of profibrotic myofibroblasts40. This research demonstrates the importance of considering the downstream myofibroblast activity of the tissue stroma when designing biomaterials that specifically target macrophage polarization for fibrosis resolution.

In a study published by Singh et al., researchers (Fig. 2) consider this crosstalk when developing an IPF therapeutic using mannosylated albumin nanoparticles designed to target the mannose receptor CD206, which is up-regulated in Mo-AMs. In their experiment, intravenously administered nanoparticles delivering a TGF-β-siRNA payload were preferentially internalized by Mo-AMs in the lung that were actively expressing the TGF-β cytokine41. Five days after bleomycin-induced fibrosis, the nanoparticles significantly reduced cytokine levels of pro-fibrotic TGF-β and IL-1β in lung tissue homogenates, which correlated with decreased disease severity as observed in lung histology and functional tests. The authors attribute this mitigation of fibrosis to reduced pathologic crosstalk between the M2-like macrophages and proximal fibrogenic fibroblasts41. A similar macrophage-targeting strategy was also demonstrated to be advantageous by Ghebremedhin and collaborators in a bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis mouse model42. Subcutaneous delivery of a host-defense-derived peptide targeting CD206+ cells three days following bleomycin administration, led to selective modulation of the M2-like Mo-AMs. Specifically, RP-832c induced repolarization of the M2-like macrophages to the M1 phenotype (as described by a shift to bacterial phagocytic activity)43 or triggered apoptosis in the CD206+ macrophage population. This resulted in a reduction of downstream pro-regenerative cytokines, which consequently reduced myofibroblast activity and ECM deposition while improving lung structure. These observations correspond to previous studies that demonstrated the specific role infiltrating monocytes play in responding to TGF-β and the ability to mitigate the fibroblast dysregulation if this population of macrophages is reduced42.

Both studies discussed here illustrate mitigation of fibrosis progression at lung mucosal sites using technologies that rely on reducing infiltration of circulating monocytes to diminish pathologic crosstalk between polarized macrophage populations and fibroblasts. To expand upon the findings illustrated by both papers, it would be interesting to develop biomaterials that not only are target-specific (CD206+ monocyte-macrophages) but also stimuli-responsive. In the case of diseases like IPF, where a positive-feedback loop exists between dysregulated cytokines and the ECM, acute exacerbations of the disease are a concern44,45. Developing a biomaterial, that confers immune memory for exacerbations of fibrotic conditions can prevent the need for multiple administrations of a therapeutic and provide a crutch for maintaining long-term tissue homeostasis.

Mannosylated albumin nanoparticles can be utilized to preferentially target CD206+ macrophages to reduce pro-fibrotic cytokine activity and thereby reverse pathologic myofibroblast deposition and ECM remodeling41.

Local delivery strategies to increase mucosal immune responses

Broadening the utility of immunomodulatory biomaterials requires delivery strategies where targets can be reached with precision to stringently control the immune phenotype. Current therapeutic options to treat pulmonary chronic inflammation in the case of IPF or following infections such as SARS-CoV-2 primarily fall short when trying to cross mucosal tissue barriers and engage local immune cells. Thus, engineering biomaterials such that they are amenable to local delivery routes to access the lower respiratory tract and raise effective mucosal immune responses are an important research area in biomaterial design. Molecules delivered via an aerosol route can achieve up to 100 times higher concentrations within the lung compared to the oral route of delivery46. This, in turn, makes aerosolized therapeutics more capable of engaging local APCs such as dendritic cells and alveolar macrophages47.

Application of an inhalable therapy for treating chronic inflammatory diseases in the lungs was recently demonstrated by the Cheng group with the delivery of lung spheroid cell secretomes and exosomes to promote lung repair in pulmonary fibrosis48. Delivery of these cell-based therapies into the respiratory space had a significant influence on modulating the lung immune microenvironment while also restoring tissue architecture and function in both bleomycin and silica models of pulmonary fibrosis in mice. Cytokine analysis of mouse serum from the secretome and exosome treatment groups indicated a downregulation of monocyte-chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1), which has previously been reported to play a role in lung inflammation49. Proteomic analyses used to elucidate the molecular mechanisms of the secretome-mediated repair pathway indicated an overall downregulation in the expression of the myofibroblast marker α-SMA and the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-4, while MMP-2 activity was upregulated48. The authors of this paper attribute this to the role select matrix metalloprotease enzymes play in late-stage fibrosis tissue repair, thus highlighting the connection between ECM proteins and anti-inflammatory mediators during the resolution stage of chronic inflammation.

Building on this foundational exosome work in the context of pulmonary diseases, Wang and collaborators recently demonstrated the effectiveness of inhaled biomaterials and therapeutics for infectious disease applications with a consideration towards preemptively reducing chronic inflammation-associated tissue fibrosis. In their 2022 paper, the researchers designed RBD-Exo VLP, a virus-like particle (VLP) utilizing exosomes as a delivery vehicle for the SARS-CoV-2 receptor-binding domain (RBD)50. Inhalation delivery of this exosome-based VLP vaccine offered significant advantages in increasing antigen availability to lung-resident APCs and consequently promoting mucosal antibody and T-cell responses. In comparison to their liposome controls, the authors hypothesized that the exosome-derived VLPs had better distribution within the lung parenchyma and APC internalization because of shared surface proteins and membrane features. When administered directly to the respiratory tract via nebulization, the VLPs stimulated the production of antigen-specific IgA antibodies in the airways and tissue, even in the absence of adjuvant. Furthermore, the inhaled VLPs also enhanced TH1-biased cellular responses, which were significant in promoting viral clearance while reducing potential vaccine-associated airway restructuring or fibrosis. This was reflected in their in vivo study when the researchers challenged hamsters with high-dose SARS-CoV-2 following administrations of the RBD-Exo VLP vaccine. Histological data revealed a reduction of fibrotic pulmonary lesions in the treatment groups in comparison to the PBS control groups, which also corroborated the protective antibody titers measured. Additionally, neutrophil myeloperoxidase (MPO)-positive cells were reduced in the lungs of the RBD-Exo treatment group, reflecting a controlled inflammatory involvement, as previous literature has indicated the role of neutrophil hyperactivity as an agent of aberrant ECM turnover and lung fibroblast proliferation50,51. Taken together, this study highlights the role that local delivery plays in raising mucosal immunity to provide both immediate and durable protection in the case of SARS-CoV-2 and similar respiratory infections that can lead to long-term chronic inflammation if left untreated50.

Both articles described in this section highlight the advantage local delivery provides in preventing the development of fibrosis, whether initiated by an infectious disease or progression of a chronic inflammatory state. However, an important consideration to be made with the introduction of therapeutic biomaterials directly into the lungs is the development of iBALT structures. While both papers addressed changes in tissue architecture, closer inspection of the type and organization of recruited myeloid and lymphoid cells can provide information regarding the repair timeline and the role biomaterials can play in restoring tissue homeostasis. With this information, biomaterial therapeutics can be tailored to either 1) take advantage of iBALT formation to quickly eliminate foreign insults capable of inducing chronic inflammation or 2) suppress iBALT persistence to prevent responses against self-antigens and downstream tissue modifications that result in poor functional outputs.

Biomaterials for treating chronic inflammation in the digestive tract

Dysregulated, chronic inflammatory responses at the intestinal mucosal site can lead to the development of long-term health consequences, including intestinal bowel disease, fibrosis, and gastrointestinal cancer52,53, emphasizing the need to engineer next-generation therapies to mitigate chronic inflammation within the intestines. Clinical manifestations of chronic intestinal inflammation include ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD), together referred to as IBD. While IBD etiology is multifactorial and complex, there is a common understanding that IBD development can be traced to dysregulated mucosal immune responses to the gut microbiome and autologous tissue in response to environmental triggers in patients with genetic predisposition54. In the United States alone, IBD is estimated to impact between 2.4 and 3.1 million people, and its prevalence is expected to continue to increase55,56. The current treatment landscape includes first-line amino-salicylates (5-ASA), corticosteroids, methotrexate, and thiopurine immunomodulators for moderate cases of IBD, and Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors and biologics against a variety of inflammatory cytokines and integrins for severe cases of IBD57. For patients with moderate-to-severe IBD, prolonged reliance on biologics can result in infections and a loss in treatment responsiveness due to targeting of dominant cytokines or generation of anti-drug antibodies (ADAs) against the infused mAbs58,59. Anti-TNF monoclonal antibodies infliximab and adalimumab, for example, had a 60.0% and 68.4% loss of response by year three, respectively, associated with a 44.0% and 20.3% incidence of ADAs, respectively60. These and other shortcomings of current treatments and the increasing prevalence of IBD motivate further development of innovative strategies to combat chronic intestinal inflammation.

The effective delivery of therapeutic agents to the site of intestinal inflammation is difficult, considering the various barriers, including drastic changes in pH, the presence of lytic enzymes, and dense layers of polysaccharide mucus. Because of the delivery challenges, many biomaterial strategies within this therapeutic area focus on delivering small molecule immunosuppressants via micro- and nanoscale delivery systems, which have been comprehensively reviewed by others61,62. This perspective section instead focuses on biomaterials that are directly immunomodulatory and successfully reprogram the inflammatory state within the gastrointestinal tract.

Cell-adhesion targeting to modulate intestinal inflammation

Gut homeostasis is mediated primarily by the mucosal epithelium and mucus barrier, commensal bacteria, and the resident immune cells63. The epithelial cells and mucus layer physically shield the underlying tissue, while resident immune cells facilitate tolerance towards healthy, commensal bacteria and food antigens. Disruption in gut homeostasis can result in an inappropriate innate immune response to intestinal bacteria, leading to aberrant adaptive inflammation and tissue damage seen in intestinal chronic inflammatory diseases64. Innate immune cells, including dendritic cells, macrophages, and neutrophils, release pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, resulting in cell migration and infiltration into the intestinal tissue. Circulating neutrophils, monocytes, and lymphocytes interact with tissue integrin ligands on the surface of vessels and extravasate into the tissue, where they secrete inflammatory molecules, further contributing to the inflammatory cascade within the intestines65. Cellular infiltration into the intestinal tissue is a hallmark of IBD and has been clinically validated as a target for reducing pathogenic inflammation. Patients with IBD tend to overexpress gut-tropic integrins and cell adhesion molecules within inflamed intestinal tissue, compared to their healthy counterparts, directly leading to enhanced cell infiltration and inflammation within the intestines66. Various anti-integrin monoclonal antibody therapeutics, including natalizumab, vedolizumab, and ontamalimab, have been designed to block interactions between cell adhesion molecules and leukocytes to prevent excess cell infiltration into the intestinal tissue. While these mAbs demonstrate therapeutic efficacy in some patient groups, primary and secondary non-response rates remain hurdles; for example, in a recent clinical trial of ontamalimab, 52.7% of originally responding patients experienced relapse67.

Motivated by the unmet need for strategies to address chronic intestinal inflammation in CD, researchers at Northwestern University have developed an approach to reduce cellular infiltration in the intestines utilizing lipid-conjugated peptide sequences derived from uteroglobin protein. This study was a collaborative effort between researchers working in the urologic, gastrointestinal, and vascular regeneration space, led by Arun Sharma and Samuel Stupp, aimed at designing a platform to efficiently deliver, protect, and present a bioactive peptide sequence in the inflammatory milieu of the small intestine. Their engineered peptide amphiphiles self-assemble into supramolecular nanofiber structures with high aspect ratios and allow for high-density display of the bioactive peptides68. The peptide sequences, called antiflammins (AFs), have demonstrated pleiotropic, anti-inflammatory properties, including the ability to reduce leukocyte adhesion, accumulation, and function in inflamed tissue via reduced adhesion molecule expression (Fig. 3)69,70. When injected directly into lesions in a murine model of ileitis, anti-inflammatory peptide amphiphiles (AIF-PAs) led to a significant decrease in the expression of adhesion/trafficking molecules CD62L (L-selectin) and CD18 and decreased infiltration of CD68+ macrophages/mononuclear phagocytes, CD4+ lymphocytes, CD11c+ myeloid-derived cells, and MCT+ mast cells. Further, the treatment led to reductions in pro-inflammatory cytokines and an increase in pro-regenerative cytokine concentration within the lamina propria. Unexpectedly, AIF-PAs also led to a re-polarization of lesion-associated macrophages towards an M2-like, CD206 + , pro-regenerative phenotype, encouraging the authors to apply these assemblies to murine models of urethroplasty, where they observed inflammation resolution and angiogenesis71. Altogether, the researchers leveraged antiflammin peptide nanofibers (AIF-PAs) to reduce pathogenic inflammation and reprogrammed the mucosal immune response towards a pro-regenerative state. These findings further support the notion that modulating the expression of cell adhesion molecules and integrins can be used to mitigate gastrointestinal inflammation. and that antiflammin-based biomaterial structures may be useful for accomplishing this.

Peptide amphiphiles, developed by the Sharma and Stupp groups, decrease the expression of adhesion molecules within inflamed tissue, resulting in a reduction in infiltrating neutrophils68. HABN nanoparticles, developed by the Moon group, have demonstrated potent scavenging of ROS within inflamed gastrointestinal tissue76.

While this strategy is innovative in concept and application, it relies on direct injection into the intestinal lesions, which may limit systemic immunomodulation and may be specifically beneficial for patients with severe CD where surgery is required to resect damaged tissue. As highlighted in the article, the authors acknowledge this as a major shortcoming and briefly discuss further materials engineering to optimize the formulation for oral delivery, including decorating the AIF-PAs with polyethylene glycol (PEG) and increasing bioactive peptide density. Further, like many studies regarding biomaterials, a larger emphasis should be placed on more extensive immune profiling, including more specificity regarding lesion-infiltrating immune cells and their respective expression markers following treatment. This has been recently highlighted in a comment published in Nature Reviews Bioengineering by Doloff and colleagues72; and we echo their call for more well-rounded immune profiling. Overall, however, the collaborative work from Northwestern University moves the needle for the use of peptide-based biomaterials for modulation of chronic intestinal inflammation via adhesion molecule expression and resulting immune infiltration.

ROS scavenging to reduce inflammatory cues

ROS are oxygen-containing molecules with unpaired electrons, which make them highly unstable and reactive. ROS are normally produced during metabolism and are rapidly scavenged via intracellular antioxidant systems, preventing excess ROS and oxidative stress-induced damage to cellular structures. In a healthy system, intestinal cells produce low levels of ROS to regulate gut microbes and maintain immunological homeostasis. While the pathogenesis of IBD is complex and multifactorial, overproduction of ROS is a hallmark of chronic intestinal inflammation73. The inability to scavenge excess ROS results in mucosal tissue damage, leading to an influx of microbes from the intestinal lumen and infiltration of immune cells in response, further contributing to a positive feedback loop of pathogenic inflammation.

Because of its role in inflammation and increased prevalence in intestinal mucosal tissues during chronic inflammation, many drug delivery strategies and therapeutic modalities have been engineered to respond to and neutralize ROS. Numerous delivery systems have been designed to allow for ROS-responsive release of therapeutic drugs, which are further detailed in previous reviews74,75. Instead, we will focus on a particular biomaterial strategy that directly neutralizes ROS to reduce pathogenic inflammation.

Motivated by the unmet need for strategies to address intestinal inflammation in IBD, researchers have developed an approach to reduce ROS-mediated damage in the intestines using biomaterial conjugate amphiphiles (Fig. 3)76. This work was conducted by Lee, Moon, and colleagues, with the goal of creating an immunomodulatory platform that allows for local delivery to inflamed tissues. Their engineered nanomedicine conjugates self-assemble into particles, hyaluronic acid-bilirubin nanomedicine (HABN), with a bilirubin core and a hyaluronic acid (HA) shell, leveraging the immunomodulatory effects of both components in their formulation.

Bilirubin has demonstrated immunomodulatory effects, primarily through direct ROS-scavenging properties, but also through intranuclear regulation of transcription factor Nrf2, increasing the expression of heme oxygenase (HO-1) and antioxidants77,78. HA, a glycosaminoglycan found in the synovial fluid and ECM, has also demonstrated various immunomodulatory effects, including the ability to regulate macrophage activation79, antimicrobial peptide expression in intestinal epithelial cells80, and Treg cells81, all of which contribute to a beneficial immune response and intestinal healing. While both HA and BR have been previously found to be immunomodulatory, their clinical development has been hampered due to various delivery challenges, including enzyme-mediated HA turnover and BR solubility issues; when formulated into HA-BR conjugates, both HA turnover and BR solubility were overcome. Motivated by the various delivery challenges associated with intestinal inflammation, the researchers aimed to create a platform that was both immunomodulatory and could achieve targeted intestinal delivery by creating HA-BR amphiphile conjugates (HABNs).

The HABN formulation demonstrated ROS scavenging and cytoprotective properties in vitro, encouraging further studies in an in vivo model of colitis. When administered via oral lavage, the researchers found that the platform preferentially accumulated within damaged intestinal tissues and impacted the inflammatory state of the tissue. HABN treatment specifically increased expression of tight-junction proteins and improved barrier function, decreased MPO activity and ROS-induced apoptosis within the epithelium, and altered the cytokine profile towards pro-regenerative, anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-10 and TGF-β. Interestingly, HABN treatment also impacted the gut microbiome, increasing bacterial richness, diversity, and the abundance of beneficial bacterial species.

The novel strategy outlined by Lee et al. outperformed conventional treatment regimens in a murine model of DSS-induced colitis, including 5-aminosalicyclic acid (5-ASA), methylprednisolone (MPS), and dexamethasone (DEX), in full bodyweight recovery, maintaining colon length, and reducing colonic damage and MPO activity, highlighting the potential clinical impact and encouraging further development. More recently, Lee has continued developing the HABN nanoparticle platform and has since applied the ROS-scavenging system to other disease contexts, including cancer and liver fibrosis, in more recent work82,83,84.

The biomaterial design and delivery strategy employed by Lee, Moon, and colleagues, and the resulting efficacy data, further exemplify the importance of biomaterial immunomodulation and local delivery for reducing mucosal inflammation. The preferential uptake of material by damaged tissue likely reduces potential off-target effects, and the resulting local reduction in ROS activity was efficacious in an acute murine model of DSS-induced colitis. Moving forward, evaluation in a chronic model of DSS-induced colitis may determine the durability of immunomodulation, long-term implications following ROS reduction, and efficacy in a more clinically relevant model. Additionally, as mentioned in the previous vignette, more rigorous immune profiling could elucidate the HABN’s impact on immune cell polarization, activation, and effector functions within the colonic epithelium; macrophages are key inflammatory mediators in colitis and therefore would be interesting to investigate further. Altogether, the shift towards biomaterials being used as both delivery platforms and immunomodulatory agents, like the HABN nanoparticles discussed, promises to expand opportunities to develop therapeutics for other chronic inflammatory diseases in the future.

Looking ahead: active immunotherapies

As previously described, chronic inflammatory disorders in mucosal tissues are multifactorial and arise from complex interactions between the mucosa and immune cells, motivating the development of multi-pronged approaches or the targeting of upstream molecules, such as cytokines, that play a pivotal role in orchestrating the pathogenic immune response. Analogous approaches are currently used in the clinic, where many patients turn towards passive immunotherapy biologics if their disease becomes refractory to steroids immunosuppressants85. These monoclonal antibodies generally target inflammatory mediators, including cytokines (TNF, IL-12, and IL-23) and extracellular proteins (such as integrins), to reduce and block inflammation within the tissue following systemic infusion. While this is therapeutically beneficial to some, monoclonal antibodies come with their own set of challenges, including high primary and secondary non-response rates, required long-term patient compliance with repeated infusions, and high costs.

Active immunotherapies have historically been used to vaccinate patients against foreign infection-causing agents, such as bacteria and parasites, with great success86. In more recent years, active immunotherapies have been explored for applications in inflammatory disorders. These active immunotherapies can achieve a reduction in inflammation by stimulating the patient’s own immune system to raise humoral and cellular responses against a given self- or non-self-inflammatory antigen, typically with more durable responses, limiting the need for frequent, repeated monoclonal antibody injections87,88. Active immunotherapies have been developed to raise humoral responses against a variety of inflammatory targets, including cytokines, pathogens, and angiogenic factors, all of which are relevant to the pathogenesis and sustained inflammation seen in both the lungs and gastrointestinal tract. Researchers have demonstrated improved disease outcomes in murine models of IBD with therapeutic or prophylactic administration, highlighting their potential for future pre-clinical development88. Because active immunotherapies engage the patient’s immune system and do not rely on delivering monoclonal antibodies parenterally, there is an opportunity to exploit alternative delivery routes for increased local efficacy, decreased systemic exposure, and ease of use.

Combining these trends, our group has engineered biomaterials that generate immune responses to inflammatory targets and delivered these materials directly to mucosal tissues to resolve local inflammation. We have investigated the targeting of multiple different cytokines in various disease contexts, including TNF89, IL-1790, complement anaphylatoxins91,92,93, IL-1β,94, and natural antibody epitopes such as phosphorylcholine (PC)95,96. These approaches can be divided into two categories of strategies. In the first, we have investigated ways to reproduce the therapeutic effect of passively administered biologics (i.e., monoclonal antibodies), but by inducing the generation of the antibodies continuously rather than injecting them periodically. Such an approach may have advantages over conventional monoclonal antibody treatment by avoiding the generation of ADAs that lead to the loss of therapeutic efficacy. In the second approach, we are seeking to engage auto-reactive antibody processes that already exist within humans: natural antibodies. Natural antibodies are prevalent in the human antibody repertoire, are commonly autoreactive, and serve myriad functions, including regulation of vascular wall homeostasis, clearance of apoptotic debris, and rapid response to conserved microbial epitopes97. One of the most well-characterized natural antibody epitopes is PC, which is exposed on the surface of apoptotic cells, oxidized lipids, and on some bacterial cell walls. Our interest in PC-reactive natural antibodies stems from their recognized function in clearing damaged tissue and restoring homeostasis98, which we hypothesized could be induced using carefully designed immunogens. Peptide nanofibers bearing highly multivalent PC epitopes stimulated significant anti-PC antibody responses, which were efficacious in both therapeutic and protective models of colitis95. Peptide assemblies are an attractive platform for immunogen design because they themselves are minimally inflammatory, capable of raising durable antibody responses with no adjuvant or minimal adjuvant99,100. Further, when PC-nanofibers were delivered orally, they mounted gastrointestinal and systemic humoral responses against PC, which led to improved intestinal barrier function, reduced disease severity, and reduced colon shortening in a murine model of DSS-induced colitis96. The assemblies were both stable within the GI tract and immunogenic, demonstrated by the generation of local antibody responses. We believe that this approach of engaging endogenous processes for regulating inflammation by designing immunogens capable of stimulating protective or therapeutic antibody responses holds significant promise as an alternative to current treatments based on biologics or monoclonal antibodies.

Conclusions

Mucosal sites, including the oral cavity, respiratory, digestive, and genitourinary tracts, are challenged immunologically by frequent and repeated exposure to dietary antigens, airborne particulates, and their respective microbiota. Because of this, inflammation in these tissues is normal but can also be dysregulated via a multitude of pathways. Mucosal tissue architecture lends itself to various delivery challenges, including a protective mucus layer, enzymes, and, in some locations, limiting pH conditions. Biomaterials have been used to overcome many of these delivery challenges with innovative design; more recently, there has been an emphasis on also establishing their immunomodulatory effect. Biomaterials are a diverse class of materials that can be modulated to tune various inflammatory states, as highlighted herein, yet further innovation is necessary. Biomaterials-based active immunotherapies specifically are a promising therapeutic strategy to resolve pathogenic inflammation at mucosal sites because they engage a patient’s own immune system to generate therapeutic immune responses to dampen mucosal inflammation with a potential for less frequent dosing and improved patient compliance compared to passive immunotherapies. In this perspective, we highlighted a wide range of biomaterials, all of which were designed independently and have unique characteristics, yet all of which achieve some degree of inflammation reduction in their respective models, demonstrating an overall benefit of design principle diversity and a potential for multi-pronged approaches in future work. Given the early stage of the field of Immune Engineering, this discovery-based and highly parallel approach that is a feature of the field at large can help maximize chances for uncovering particularly effective strategies and treatments. As the field matures, we advocate for continued research and development that compares various platforms, allowing for the synthesis of central biomaterial design rules surrounding immunomodulation and delivery, which will, in turn, facilitate scale-up, translation, and ultimately delivery to the patient.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

-

Eshaghi, B. et al. The role of engineered materials in mucosal vaccination strategies. Nat. Rev. Mater. 9, 29–45 (2024).

-

Haddad, H. F., Roe, E. F. & Collier, J. H. Expanding opportunities to engineer mucosal vaccination with biomaterials. Biomater. Sci. 11, 1625–1647 (2023).

-

Eming, S. A., Wynn, T. A. & Martin, P. Inflammation and metabolism in tissue repair and regeneration. Science. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.aam7928 (2017).

-

Wilson, M. S. et al. Bleomycin and IL-1β-mediated pulmonary fibrosis is IL-17A dependent. J. Exp. Med. 207, 535–552 (2010).

-

Schett, G. & Neurath, M. F. Resolution of chronic inflammatory disease: universal and tissue-specific concepts. Nat. Commun. 9, 3261 (2018).

-

Griseri, T., Asquith, M., Thompson, C. & Powrie, F. OX40 is required for regulatory T cell–mediated control of colitis. J. Exp. Med. 207, 699–709 (2010).

-

Ninnemann, J. et al. TNF hampers intestinal tissue repair in colitis by restricting IL-22 bioavailability. Mucosal Immunol. 15, 698–716 (2022).

-

Sandler, N. G., Mentink-Kane, M. M., Cheever, A. W. & Wynn, T. A. Global gene expression profiles during acute pathogen-induced pulmonary inflammation reveal divergent roles for Th1 and Th2 responses in tissue repair1. J. Immunol. 171, 3655–3667 (2003).

-

Tu, Z. et al. Design of therapeutic biomaterials to control inflammation. Nat. Rev. Mater. 7, 557–574 (2022).

-

Birchenough, G. M. H., Johansson, M. E., Gustafsson, J. K., Bergström, J. H. & Hansson, G. C. New developments in goblet cell mucus secretion and function. Mucosal Immunol. 8, 712–719 (2015).

-

Sluis et al. Muc2-deficient mice spontaneously develop colitis, indicating that MUC2 is critical for colonic protection. Gastroenterology 131, 117–129 (2006).

-

Knoop, K. A., McDonald, K. G., McCrate, S., McDole, J. R. & Newberry, R. D. Microbial sensing by goblet cells controls immune surveillance of luminal antigens in the colon. Mucosal Immunol 8, 198–210 (2015).

-

Cohen-Kedar, S. et al. Human intestinal epithelial cells can internalize luminal fungi via LC3-associated phagocytosis. Front. Immunol 14, 1142492 (2023).

-

Feng, X. et al. Tuft cell IL-17RB restrains IL-25 bioavailability and reveals context-dependent ILC2 hypoproliferation. Nat. Immunol. 26, 567–581 (2025).

-

Britton, G. J. et al. Microbiotas from humans with inflammatory bowel disease alter the balance of gut Th17 and RORγt+ regulatory T cells and exacerbate colitis in mice. Immunity 50, 212–224.e4 (2019).

-

Caruso, R. et al. A specific gene-microbe interaction drives the development of Crohn’s disease–like colitis in mice. Sci. Immunol. 4, eaaw4341 (2019).

-

Atarashi, K. et al. Ectopic colonization of oral bacteria in the intestine drives TH1 cell induction and inflammation. Science 358, 359–365 (2017).

-

Silva-Sanchez, A. & Randall, T. D. Anatomical uniqueness of the mucosal immune system (GALT, NALT, iBALT) for the induction and regulation of mucosal immunity and tolerance. Mucosal Vaccines 25, 21–54 https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-811924-2.00002-X (2020).

-

Hwang, J. Y. et al. Inducible bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue (iBALT) attenuates pulmonary pathology in a mouse model of allergic airway disease. Front. Immunol 11, 570661 (2020).

-

Naessens, T. et al. Human lung conventional dendritic cells orchestrate lymphoid neogenesis during chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 202, 535–548 (2020).

-

Rangel-Moreno, J. et al. Inducible bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue (iBALT) in patients with pulmonary complications of rheumatoid arthritis. J. Clin. Invest. 116, 3183–3194 (2006).

-

Coombes, J. L. et al. A functionally specialized population of mucosal CD103+ DCs induces Foxp3+ regulatory T cells via a TGF-β– and retinoic acid–dependent mechanism. J. Exp. Med. 204, 1757–1764 (2007).

-

Murai, M. et al. Interleukin 10 acts on regulatory T cells to maintain expression of the transcription factor Foxp3 and suppressive function in mice with colitis. Nat. Immunol. 10, 1178–1184 (2009).

-

Campbell, C. et al. Extrathymically generated regulatory T cells establish a niche for intestinal border-dwelling bacteria and affect physiologic metabolite balance. Immunity 48, 1245–1257.e9 (2018).

-

Traxinger, B. R., Richert-Spuhler, L. E. & Lund, J. M. Mucosal tissue regulatory T cells are integral in balancing immunity and tolerance at portals of antigen entry. Mucosal Immunol. 15, 398–407 (2022).

-

Gieseck, R. L., Wilson, M. S. & Wynn, T. A. Type 2 immunity in tissue repair and fibrosis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 18, 62–76 (2018).

-

Wynn, T. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of fibrosis. J. Pathol. 214, 199–210 (2008).

-

Murray, L. A. et al. Hyper-responsiveness of IPF/UIP fibroblasts: interplay between TGFβ1, IL-13 and CCL2. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 40, 2174–2182 (2008).

-

Amara, N. et al. NOX4/NADPH oxidase expression is increased in pulmonary fibroblasts from patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and mediates TGFβ1-induced fibroblast differentiation into myofibroblasts. Thorax. https://doi.org/10.1136/thx.2009.113456 (2010).

-

Barry-Hamilton, V. et al. Allosteric inhibition of lysyl oxidase–like-2 impedes the development of a pathologic microenvironment. Nat. Med. 16, 1009–1017 (2010).

-

Ahamad, N. et al. Immunomodulatory nanosystems for treating inflammatory diseases. Biomaterials 274, 120875 (2021).

-

Nakkala, J. R., Li, Z., Ahmad, W., Wang, K. & Gao, C. Immunomodulatory biomaterials and their application in therapies for chronic inflammation-related diseases. Acta Biomater. 123, 1–30 (2021).

-

Mata, R. et al. The dynamic inflammatory tissue microenvironment: signality and disease therapy by biomaterials. Research 2021, 4189516 (2021).

-

Sudduth, E. R., Trautmann-Rodriguez, M., Gill, N., Bomb, K. & Fromen, C. A. Aerosol pulmonary immune engineering. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 199, 114831 (2023).

-

Woodward, I. R. & Fromen, C. A. Recent developments in aerosol pulmonary drug delivery: new technologies, new cargos, and new targets. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-bioeng-110122-010848 (2024).

-

Gopallawa, I., Dehinwal, R., Bhatia, V., Gujar, V., Chirmule, N. A four-part guide to lung immunology: invasion, inflammation, immunity, and intervention. Front. Immunol. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1119564/full (2023).

-

Smyth, T., Payton, A., Hickman, E., Rager, J. E. & Jaspers, I. Leveraging a comprehensive unbiased RNAseq database to characterize human monocyte-derived macrophage gene expression profiles within commonly employed in vitro polarization methods. Sci. Rep. 14, 26753 (2024).

-

Xue, J. et al. Transcriptome-based network analysis reveals a spectrum model of human macrophage activation. Immunity 40, 274–288 (2014).

-

Younesi, F. S., Miller, A. E., Barker, T. H., Rossi, F. M. V. & Hinz, B. Fibroblast and myofibroblast activation in normal tissue repair and fibrosis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 25, 617–638 (2024).

-

Lodyga, M. et al. Cadherin-11-mediated adhesion of macrophages to myofibroblasts establishes a profibrotic niche of active TGF-β. Sci. Signal. 12, eaao3469 (2019).

-

Singh, A. et al. Nanoparticle targeting of de novo profibrotic macrophages mitigates lung fibrosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2121098119 (2022).

-

Ghebremedhin, A. et al. A novel CD206 Targeting peptide inhibits bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice. Cells 12, 1254 (2023).

-

Jaynes, J. M. et al. Mannose receptor (CD206) activation in tumor-associated macrophages enhances adaptive and innate antitumor immune responses. Sci. Transl. Med. 12, eaax6337 (2020).

-

Ley, B. et al. Pirfenidone reduces respiratory-related hospitalizations in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 196, 756–761 (2017).

-

Costabel, U. et al. Efficacy of nintedanib in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis across prespecified subgroups in INPULSIS. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 193, 178–185 (2016).

-

Adjei, A. & Garren, J. Pulmonary delivery of peptide drugs: effect of particle size on bioavailability of leuprolide acetate in healthy male volunteers. Pharm. Res. 7, 565–569 (1990).

-

Thornton, E. E. et al. Spatiotemporally separated antigen uptake by alveolar dendritic cells and airway presentation to T cells in the lung. J. Exp. Med. 209, 1183–1199 (2012).

-

Dinh, P.-U. C. et al. Inhalation of lung spheroid cell secretome and exosomes promotes lung repair in pulmonary fibrosis. Nat. Commun. 11, 1064 (2020).

-

Car, B. D. et al. Elevated IL-8 and MCP-1 in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and pulmonary sarcoidosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 149, 655–659 (1994).

-

Wang, Z. et al. Exosomes decorated with a recombinant SARS-CoV-2 receptor-binding domain as an inhalable COVID-19 vaccine. Nat. Biomed. Eng. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41551-022-00902-5 (2022).

-

Jegal, Y. The role of neutrophils in the pathogenesis of IPF. Korean J. Intern Med. 37, 945–946 (2022).

-

Chen, H.-J., Liang, G.-Y., Chen, X. & Du, Z. Acute or chronic inflammation role in gastrointestinal oncology. World J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 14, 1600–1603 (2022).

-

Wang, Y. et al. Intestinal fibrosis in inflammatory bowel disease and the prospects of mesenchymal stem cell therapy. Front. Immunol 13, 835005 (2022).

-

Pizarro, T. T. et al. Challenges in IBD research: preclinical human IBD mechanisms. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 25, S5–S12 (2019).

-

Lewis, J. D. et al. Incidence, prevalence, and racial and ethnic distribution of inflammatory bowel disease in the United States. Gastroenterology 165, 1197–1205 (2023).

-

Ye, Y., Manne, S., Treem, W. R. & Bennett, D. Prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in pediatric and adult populations: recent estimates from large national databases in the United States, 2007–2016. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. https://doi.org/10.1093/ibd/izz182 (2019).

-

Muzammil, M. A. et al. Advancements in inflammatory bowel disease: a narrative review of diagnostics, management, epidemiology, prevalence, patient outcomes, quality of life, and clinical presentation. Cureus https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.41120 (2023).

-

Salvana, E. M. T. & Salata, R. A. Infectious complications associated with monoclonal antibodies and related small molecules. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 22, 274–290 (2009).

-

Roda, G., Jharap, B., Neeraj, N. & Colombel, J.-F. Loss of response to anti-TNFs: definition, epidemiology, and management. Clin. Transl. Gastroenterol 7, e315 (2016).

-

Chanchlani, N. et al. Mechanisms and management of loss of response to anti-TNF therapy for patients with Crohn’s disease: 3-year data from the prospective, multicentre PANTS cohort study. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 9, 521–538 (2024).

-

Wang, C.-P. J. et al. Biomaterials as therapeutic drug carriers for inflammatory bowel disease treatment. J. Control. Release 345, 1–19 (2022).

-

Jori, C. et al. Biomaterial-based strategies for immunomodulation in IBD: current and future scenarios. J. Mater. Chem. B 11, 5668–5692 (2023).

-

Fournier, B. M. & Parkos, C. A. The role of neutrophils during intestinal inflammation. Mucosal Immunol. 5, 354–366 (2012).

-

Danne, C., Skerniskyte, J., Marteyn, B. & Sokol, H. Neutrophils: from IBD to the gut microbiota. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 21, 184–197 (2024).

-

Kelly, A. J. & Long, A. Targeting T-cell integrins in autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 215, 15–26 (2024).

-

Gubatan, J. et al. Anti-integrins for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: current evidence and perspectives. Clin. Exp. Gastroenterol. 14, 333–342 (2021).

-

D’Haens, G. R. et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of the anti-mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule-1 monoclonal antibody ontamalimab (SHP647) for the treatment of Crohn’s disease: the OPERA II study. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. https://doi.org/10.1093/ibd/izab215 (2021).

-

Bury, M. I. et al. Self-assembling nanofibers inhibit inflammation in a murine model of Crohn’s-disease-like ileitis. Adv. Ther. 4, 2000274 (2021).

-

MIELE, L. Antiflammins: bioactive peptides derived from uteroglobin. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 923, 128–140 (2000).

-

Miele, L., Cordella-Miele, E., Facchiano, A. & Mukherjee, A. B. Novel anti-inflammatory peptides from the region of highest similarity between uteroglobin and lipocortin I. Nature 335, 726–730 (1988).

-

Chan, Y. Y. et al. Effects of anti-inflammatory nanofibers on urethral healing. Macromol. Biosci. 21, 2000410 (2021).

-

Stelzel, J. L., Schneck, J. P., Mao, H.-Q. & Doloff, J. C. Oversimplified immunology is holding biomaterials back. Nat. Rev. Bioeng. 3, 523–525 (2025).

-

Muro, P. et al. The emerging role of oxidative stress in inflammatory bowel disease. Fron. Endocrinol 15, 1390351 (2024).

-

Saravanakumar, G., Kim, J. & Kim, W. J. Reactive-oxygen-species-responsive drug delivery systems: promises and challenges. Adv. Sci. 4, 1600124 (2017).

-

Xie, J. et al. Natural dietary ROS scavenger-based nanomaterials for ROS-related chronic disease prevention and treatment. Chem. Eng. J. 490, 151756 (2024).

-

Lee, Y. et al. Hyaluronic acid–bilirubin nanomedicine for targeted modulation of dysregulated intestinal barrier, microbiome and immune responses in colitis. Nat. Mater. 19, 118–126 (2020).

-

Liu, J. et al. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) scavenging biomaterials for anti-inflammatory diseases: from mechanism to therapy. J. Hematol. Oncol. 16, 116 (2023).

-

Qaisiya, M., Coda Zabetta, C. D., Bellarosa, C. & Tiribelli, C. Bilirubin mediated oxidative stress involves antioxidant response activation via Nrf2 pathway. Cell. Signal. 26, 512–520 (2014).

-

Rayahin, J. E., Buhrman, J. S., Zhang, Y., Koh, T. J. & Gemeinhart, R. A. High and low molecular weight hyaluronic acid differentially influence macrophage activation. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 1, 481–493 (2015).

-

Hill, D. R., Kessler, S. P., Rho, H. K., Cowman, M. K. & De La Motte, C. A. Specific-sized hyaluronan fragments promote expression of human β-defensin 2 in intestinal epithelium. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 30610–30624 (2012).

-

Bollyky, P. L. et al. Intact extracellular matrix and the maintenance of immune tolerance: high molecular weight hyaluronan promotes persistence of induced CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. J. Leukoc. Biol. 86, 567–572 (2009).

-

Lee, Y. et al. Hyaluronic acid-bilirubin nanomedicine-based combination chemoimmunotherapy. Nat. Commun 14, 4771 (2023).

-

Lee, S., Lee, S. A., Shinn, J. & Lee, Y. Hyaluronic acid-bilirubin nanoparticles as a tumor microenvironment reactive oxygen species-responsive nanomedicine for targeted cancer therapy. Int. J. Nanomed. 19, 4893–4906 (2024).

-

Shinn, J. et al. Antioxidative hyaluronic acid–bilirubin nanomedicine targeting activated hepatic stellate cells for anti-hepatic-fibrosis therapy. ACS Nano 18, 4704–4716 (2024).

-

Di Paolo, A. & Luci, G. Personalized medicine of monoclonal antibodies in inflammatory bowel disease: pharmacogenetics therapeutic drug monitoring, and beyond. Front Pharmacol 11, 610806 (2021).

-

Montero, D. A. et al. Two centuries of vaccination: historical and conceptual approach and future perspectives. Front. Public Health 11, (2024).

-

Nakagami, H., Hayashi, H., Shimamura, M., Rakugi, H. & Morishita, R. Therapeutic vaccine for chronic diseases after the COVID-19 Era. Hypertension Res. 44, 1047–1053 (2021).

-

Liu, Y. & Liao, F. Vaccination therapy for inflammatory bowel disease. Hum. Vaccin Immunother. 19, 2259418 (2023).

-

Mora-Solano, C. et al. Active immunotherapy for TNF-mediated inflammation using self-assembled peptide nanofibers. Biomaterials 149, 1–11 (2017).

-

Shores, L. S. et al. Multifactorial design of a supramolecular peptide anti-IL-17 vaccine toward the treatment of psoriasis. Front. Immunol 11, 1855 (2020).

-

Hainline, K. M. et al. Modular complement assemblies for mitigating inflammatory conditions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2018627118 (2021).

-

Hainline, K. M. et al. Active immunotherapy for C5a-mediated inflammation using adjuvant-free self-assembled peptide nanofibers. Acta Biomater. 179, 83–94 (2024).

-

Freire Haddad, H., Roe, E. F., Xie Fu, V., Curvino, E. J. & Collier, J. H. Multi-target peptide nanofiber immunotherapy diminishes complement anaphylatoxin activity in acute inflammation. Adv. Healthcare Mater. https://doi.org/10.1002/adhm.202402546 (2024).

-

Shetty, S. et al. Anti-cytokine active immunotherapy based on supramolecular peptides for alleviating IL-1β-mediated inflammation. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2401444 (2024).

-

Curvino, E. J. et al. Engaging natural antibody responses for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease via phosphorylcholine-presenting nanofibres. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 8, 628–649 (2023).

-

Curvino, E. J. et al. Supramolecular peptide self-assemblies facilitate oral immunization. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 10, 3041–3056 (2024).

-

Holodick, N. E., Rodr¡guez-Zhurbenko, N. & Hern ndez, A. M. Defining natural antibodies. Front. Immunol 8, 872 (2017).

-

Grönwall, C., Vas, J. & Silverman, G. J. Protective roles of natural IgM antibodies. Front. Immunol 3, 66 (2012).

-

Rudra, J. S., Tian, Y. F., Jung, J. P. & Collier, J. H. A self-assembling peptide acting as an immune adjuvant. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 622–627 (2010).

-

Chen, J. et al. The use of self-adjuvanting nanofiber vaccines to elicit high-affinity B cell responses to peptide antigens without inflammation. Biomaterials 34, 8776–8785 (2013).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Shamitha Shetty for their helpful advice and feedback. Figures were designed using both BioRender.com and bioart.niaid.nih.gov. Research on active immunotherapies in our group is supported by the United States National Institutes of Health, grants 5 R01 AI67300, 5 R01 AI172151, and 5 R21 EB033687.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

J.H.C. is listed as an inventor on multiple patents and patent applications relating to active immunotherapies based on peptide assemblies.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Babb, L.M., Kulapurathazhe, M.J. & Collier, J.H. Immunomodulatory biomaterials for treating chronic inflammation at mucosal sites. npj Biomed. Innov. 2, 46 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44385-025-00052-8

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

Version of record:

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44385-025-00052-8