Introduction

Kaempferia parviflora, an important ginger plant is referred to as Thai ginseng or krachai-dum and belongs to the family Zingiberaceae. It is available in India, Bangladesh, Thailand, Myanmar, Cambodia and Burma1. K. parviflora is a tropical edible plant that has long been valued for its culinary uses and traditional medicinal benefits2. It is referred as “black ginger” because of its blackish purple rhizome. K. parviflora is a herbaceous perennial with tuberous roots, small white blossoms with a purple border. In moist, damp soil with temperatures between 30 and 35 °C, it can Reach a height of 90 cm3. Thai locals utilize the plant to cure colic diseases for human health. Many researches have been done in K. parviflora for various medicinal properties as presence of methoxyflavonoids in rhizome extracts of ethanol and chloroform using silica gel column chromatography4.

K. parviflora is traditionally used in Southeast Asia for digestive health, allergies, sexual function, and overall nourishment. It exhibits antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-obesity, anticancer, vascular, and antimicrobial effects. The rhizome, rich in polymethoxyflavones, holds strong promise for various therapeutic applications5. Cancer is still a leading cause of death worldwide, and its silent development and vague symptoms frequently make early detection difficult. However, because of its non-selective cytotoxicity, chemotherapy has serious side effects, and many patients cannot afford the expensive new chemotherapeutics. As a result, researchers are increasingly exploring targeted therapies with a focus on herbal compounds as alternative, cost-effective solutions6. Several pharmacological activities of K. parviflora have been documented, including its anti-proliferative and antimetastatic effects across various cancer types. These effects have been demonstrated in highly aggressive ovarian cancer cells (SKOV3)7as well as in cervical (HeLa)6 leukemic8,9 bile duct (HuCCA-1 and RMCCA-1)10 lung (A549)11 and melanoma12 cancer cell lines.

Beyond its anticancer properties, K. parviflora has demonstrated antimicrobial activity, contributing significantly to Reducing the global burden of infectious diseases. Antimicrobial activity is the process to inhibit the microbes causing diseases. It may be antifungal, antibacterial or antiviral operating through various mechanisms to inhibit infections. Agar disc-diffusion testing, which was created in the 1940s, is a common practice for antimicrobial testing in many clinical labs. Ethanolic rhizome extract from K. parviflora has been reported to exhibit antibacterial activity against human infections, bacteria, yeast, and dermatophyte fungi. It had potent antifungal effects on dermatophytes for which dermatophytic infections could be treated traditionally using K. parviflora13. Extracts and oil of K. parviflora also showed antimicrobial results14. Phenolic compounds and flavonoids are important phytochemicals for their diverse bio activities, including anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anticancer effects. Research into the specific phenolic and flavonoid profiles of K. parviflora could provide insights into the mechanisms underlying its health benefits15.

The present study investigates the chemical composition and biological activities of Kaempferia parviflora rhizome essential oil, with a particular focus on its GC×GC-TOF-MS analysis, antimicrobial, antioxidant, and cytotoxic properties. GC×GC-TOF-MS is one of the most advanced techniques in metabolomics, capable of detecting hundreds of metabolites with significantly higher speed, sensitivity, and accuracy than traditional GC-MS methods. This study provides a comprehensive phytochemical characterization of K. parviflora essential oil and evaluates its antimicrobial and antioxidant activities through biochemical assays. Furthermore, the cytotoxic potential of the oil was assessed using the MTT assay against a broad spectrum of human cancer cell lines, including HEK-293 (kidney), A549 (lung carcinoma), A431 (skin cancer), HCT-15 (hepatocellular adenocarcinoma), KB (oral cancer), LN-18 (glioblastoma), Panc-1 (pancreatic cancer), and SKBR-3 (breast cancer). Despite the extensive medicinal applications of K. parviflora, limited research is available on the chemical constituents of its essential oil, yet no reports exist on its GC×GC-TOF-MS profiling along with its bioactivities from Eastern India. The findings highlight the potential therapeutic applications of K. parviflora essential oil, supporting its traditional medicinal uses and providing insights into its role in modern pharmaceutical development.

Materials and methods

Collection of plant material

The plants were brought from Kandhamal district, Odisha (20.1342° N, 84.0167° E) and were identified by Prof. P. C. Panda, Taxonomist. A voucher specimen (2559/CBT) was submitted at the Herbarium of Siksha ‘O’ Anusandhan University, Bhubaneswar, Odisha and the plant was maintained at Centre for Biotechnology medicinal garden for further use.

Extraction of rhizome essential oil

The fresh rhizomes were rinsed in tap water and used for essential oil (EO) extraction. Approximately 500 g of sliced rhizomes were combined with 1000 ml of distilled water. EO was isolated using the hydrodistillation method using a Clevenger’s apparatus following the standardised protocol16. A flask containing sliced rhizomes was heated up to 6 h and then the separation of condensed vapour in water oil interface. The collection of oil from the top layer was transferred into a microcentrifuge tube through the collection chambers and kept at 4 °C for analysis.

GC x GC-TOF-MS analysis

The rhizome oil about 0.1 µl was analyzed using LECO Pegasus 4D Time-of-flight (TOF) mass spectrometry system consisting of Agilent 6890 A gas chromatograph provided with an Agilent 7683B automatic liquid sampler, a cold jet modulator KT-2007 and a secondary oven. The TOF spectrometer was used as a detector for analysis. The dimension column first used was Restek Rtx-5MS (30 m × 0.25 mm I.D., 0.25 mm film thickness) whereas second was Restek Rxi-17 Sil MS (2 m × 0.25 mm I.D., 0.25 mm film thickness). The oil was injected into GC x GC inlet using split mode (1:700) method. Helium served as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The mass spectrometer operated in electron impact (EI) mode with an ionization voltage of 70 eV, scanning a mass range of 30 to 350 m/z, and a detector voltage of 1620 V. The source and transfer line temperatures of the mass spectrometer were maintained at 250 °C. The primary oven program started at 50 °C for 1 min, then increased at a rate of 5 °C/min to 230 °C, which was held for 5 min, and finally ramped up at 15 °C/min to 260 °C with a 1-minute hold. The secondary oven was set with a 10 °C offset. The time of modulation was 5 s followed by hot pulse of 0.9 s and cold pulse of 1.6 s Respectively. TOF-MS was operated at a spectral acquisition rate of 100 spectra/sec. The TOF data processing software version 3.34 were used for analysis and contour plots were used for identification of the manual peaks. The various compounds were identified by comparing their mass spectra with those in the NIST library. Additional identification was achieved by calculating the linear temperature programmed retention index (LTPRI) using a homologous series of n-alkanes (C8–C20) as external References. These calculated values were then compared to bibliographic literature corresponding to the column used as the first dimension column in this study. LTPRI was determined by Vanden Dooland Kratz equation. A detected compound was accepted if it had a minimum similarity of 80% (800 out of 1000) with the library. The percentage content of each compound in the oil was calculated using the GC x GC areas17.

Statistical analysis

The data were presented as means ± standard deviation from triplicate determinations, and statistical analyses were carried out using Minitab version 17 statistical software (Minitab Inc, PA, USA). One-way ANOVA, supplemented by Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) test at a significance level of p < 0.05, was also employed.

Cell line culturing and MTT cell viability assay

Eight human cell lines, namely; Human Embryonic Kidney (HEK-293), Human alveolar lung adenocarcinoma (A549), Human skin carcinoma (A431), Human hepatocellular adenocarcinoma (HCT-15), Human oral cancer (KB), Human brain glioblastoma (LN-18), Human pancreatic carcinoma (Panc-1), and Human breast cancer (SKBR3), were procured from the National Centre for Cell Science (NCCS), Pune, India. Experimental controls included a medium control (medium without cells), a negative control (medium with cells but without the test compound), and a positive control (medium with cells treated with 5 µM Camptothecin). HEK-293, A549, A431, LN-18, Panc-1, and KB cell lines were subcultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM), while RPMI-1640 medium was used for HCT-15 cells, and McCoy’s 5 A medium was used for SKBR3 cells. All culture media were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic solution and maintained in an incubator at 5% CO₂ and 18–20% O₂. Cells were seeded at a density of 20,000 cells per well in a 96-well plate (200 µL per well) and allowed to adhere for 24, 48 and 72 h. Test samples were added at varying concentrations (12.5, 25, 50, 100 and 200 µL/mL) and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h under 5% CO₂. Following incubation, the spent medium was aspirated, and MTT Reagent was added to achieve a final concentration of 0.5 mg/mL. The plates were wrapped in aluminum foil to prevent light exposure and incubated for 3 h. Subsequently, the MTT Reagent was Removed, and 100 µL of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was added to dissolve the formazan crystals. The absorbance was measured at 570 nm using an ELISA reader. The IC₅₀ value was determined by linear regression analysis from the cell viability curve18,19.

Collection of microbial strains

The organisms used for antimicrobial activity were obtained from Microbial Type Culture Collection and Gene Bank at Chandigarh. Pure cultures from plates were inoculated onto nutrient agar plates and subcultured for 24 h at 37 °C. Inoculum was aseptically prepared adding fresh culture into 2 ml of sterile 0.145 mol/L saline tube. Cell density was adjusted to 0.5 McFarland turbidity standards to yield a bacterial suspension of 1.5 × 108cfu/ml. This standardized method was used to assess the plant samples antimicrobial activities20.

The MIC was evaluated using Clinical and Laboratory Standard Institute (CLSI) guidelines. It was followed using broth microdilution method in Mueller-Hinton Broth (MHB) at pH 7.0. The test was assessed against bacterial strains i.e. (Staphylococcus aureus (MTCC 3160), Bacillus subtilis (MTCC 441), Staphylococcus epidermis (MTCC 3086), Escherichia coli (MTCC 727), Klebsiella pneumoniae MTCC 4030) and one fungal strain (Candida albicans MTCC 3017). Test compounds underwent two-fold serial dilutions in the media. 100 µL aliquots were added per well in 96 well microtiter plates. Microbial test suspensions were adjusted to 0.5 McFarland standards, (Resulting in a 1× 106 CFU/mL (bacterial) and 1 × 104 CFU/mL). The final concentration of test compounds ranged from (1000-15.625) µg/mL. The microtiter plates were incubated for 72 h at 35 °C, and ELISA plate reader was employed for plate reading. Statistic determination was done using SPSS software21.

Disc diffusion assay

Further antimicrobial activity was assessed with the MIC range of the Respective bacteria against bacterial strains and one fungal strain using the disc diffusion method. Microbial colonies from 24-hour plates were suspended in 0.85% saline to achieve a turbidity corresponding to 0.5 McFarland standards, Resulting in 1× 106 CFU/mL (bacterial) and 1 × 104 CFU/mL (fungal) suspensions. Inoculum of 0.1 mL was used for lawn culturing over the surface of MHA and PDA plates for bacteria and fungi Respectively. 100 µl of test samples at a concentration following MIC results were taken. DMSO was used as negative control. As a positive control, norfloxacin (5 µg) was used for gram-positive bacteria, cefoperazone–sulbactam (10 µg) for gram-negative bacteria, and Clotrimazole (10 µg) for Candida sp. following EUCAST/CLSI. Incubation of plates was done for 24 h at 35 °C to assess clear zone around the growth. The experiment was conducted thrice for accuracy22.

Statistical analysis

Microsoft 365 excel was used to enter and capture data. Various graphs and tables were extracted from this data. Data was exported to SPSS 25.0 for analysis in one way analysis of variance (ANOVA). P < 0.05 was considered as significant.

DPPH assay

The DPPH radical scavenging assay was conducted following the protocol by Jena et al. (2017), with minor adjustments. A volume of 1 ml of oil at various concentrations was mixed with 1 ml of a 0.1 mM methanolic DPPH solution, and the mixture was allowed to React at room temperature for 30 min. The absorbance of the sample was measured at 517 nm. The percentage of DPPH radical inhibition was calculated using the formula: (%) inhibition = [100 * (Absorbance of control – Absorbance of test sample)/Absorbance of control]. The concentration of oil Required to inhibit 50% of the DPPH radicals was determined as the IC50 value23.

ABTS assay

The ABTS radical scavenging ability of the rhizome oil was assessed using the protocol established by Re et al. (1999), with slight modifications. An ABTS stock solution was prepared by combining 7 mM ABTS and 2.45 mM ammonium persulfate, allowing it to stand at room temperature for 16 h. The ABTS solution was then diluted with methanol to achieve an absorbance of 734 nm. Following this, 1 ml of various concentrations of oil was added to 1 ml of the ABTS solution, and the absorbance was measured at 734 nm. The percentage of ABTS radical inhibition was calculated using the same formula as in the DPPH assay. The IC50 value was determined as the concentration of oil Required to inhibit 50% of the ABTS radicals24. All our experiments were performed in triplicates to ensure precision and reproducibility.

Results and discussion

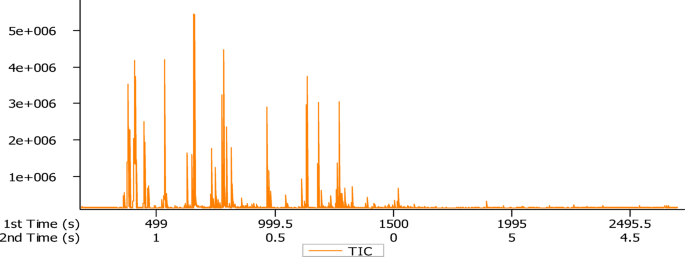

The obtained rhizome essential oil of K. parviflora was pale yellow in colour with a good aroma and the yield percentage was 0.045% (v/w) on fresh weight basis. The volatile composition of the rhizome EO was evaluated by GCxGC-TOF-MS analysis and the total ion chromatogram has been shown (Figs. 1, 2 and 3). Oil constituents were identified by comparing their mass spectra with the NIST library. In the present study, a total 129 constituents were identified through GC×GC-TOF-MS analysis (Table 1). The major constituents was found to be Benzenepropanol, à-methyl-, acetate (9.78 ± 0.01%) followed by camphene (9.39 ± 0.01%), α-pinene (7.50 ± 0.01%), linalool (5.46 ± 0.01%), camphore (5.04 ± 0.01%), notrisyl bromide (4.49 ± 0.01%), α-myrcene (4.42 ± 0.01%), 2-undecanone (3.99 ± 0.01%), α-terpineol (3.40 ± 0.01%), camphor (3.12 ± 0.01%), germacrene D (3.03 ± 0.01%), limonene (2.35 ± 0.01%), 3-decen-2-one (1.92 ± 0.01%), caryophyllene (1.77 ± 0.01%), bornyl acetate (1.66 ± 0.01%), eucalyptol (1.58 ± 0.01%), α-terpinolen (1.29 ± 0.01%), δ-elemene (1.09 ± 0.01%) respectively (Fig. 4). Earlier, Feng et al. (2023), reported that K. parviflora has a maximum essential oil concentration of 0.14%25. The oil yield percentage of K. parviflora in the present study was 0.045% which is comparatively lower than the previous reports. Investigation done by Begum et al. (2022), indicates that essential oil yields are greater when plants are grown in partial shade (0.92% w/w) as opposed to open field (0.76% w/w) conditions, with linalool being the major compound. Shade nets were shown to boost essential oil yield in K. parviflora, making them suitable for commercial farming26. According to the reports of Pitakpawasutthi et al. (2018), K. parviflora EO showed the significant components as α-copaene (11.68%), dauca-5, 8-diene (11.17%), camphene (8.73%), β-pinene (7.18%), borneol (7.05%) and linalool (6.58%) respectively27. Similar studies have been reported by Wongpia et al., (2022) showing constituents of steamdistilled essential oil of K. parviflora. According to the report, germacrene D (15.4%), α-pinene (11.2%), camphene (10.1%), borneol (9.2%), linalool (8.0%) and β-pinene (6.4%) were found to be the key constituents28. Many other reports investigated, the major components present in K. parviflora rhizomes as germacrene D, β-elemene, α-copaene and E-caryophyllene29,30. Nguyen et al., (2023) reported camphene (18.03%), β-pinene (14.25%), a-pinene (12.38%), endo-borneol (10.23%), β-copaene (8.38%), and linalool (8.20%) as the major constituents31. Major constituents of the EO are borneol and linalool as reported by Feng et al. (2023)25. Another investigation reported methyl nervonate, borneol, linalool, methyl oleate and methyl tricosanoate as its principal compounds32. Similar studies have been done where major compounds found are different than ours. Also, our study found similar compounds at different concentrations along with some new components as depicted in Table 1. Due to the limited availability of reports on GC-TOF-MS for similar analyses, we have included GC-MS results to strengthen the comprehensiveness and reliability of our findings.

t1R (Min): First dimension retention time in minutes. t2R (S): Second dimension retention time in seconds. RI EXP: Retention index from the chromatogram.

Cytotoxicity analysis revealed that among all cell lines, both K. parviflora rhizome oil and Camptothecin show decreasing IC50 values with increasing incubation time (24 h → 48 h → 72 h). SKBR3 (Breast Cancer Cells) showed the lowest IC50 at 72 h (11.79 ± 0.01 µg/mL), indicating high sensitivity. While, A431 (Skin Cancer Cells) had the highest IC50 at 24 h (288.43 ± 0.02 µg/mL), indicating lower sensitivity. A time-dependent decrease in IC50 values was observed for both K. parviflora oil and Camptothecin. This suggests that prolonged exposure increases cytotoxic effects, likely due to cumulative cellular stress and apoptosis induction. (Table 2). Others have studied methoxyflavone as an active ingredient responsible for anticancer activity33. Previously, Patanasethanont et al., (2007) reported that K. parviflora suppressed multidrug resistance associated proteins in A459 cells11. Likewise, Apoptotic cell death induction and enhanced paclitaxel or doxorubicin treatment in a promyelocytic leukemic cancer cell line was studied by Banjerdpongchai et al. (2009)9. Additionally, K. parviflora extract exhibited dose-dependent cytotoxicity in SKOV3 cells, inhibiting proliferation, migration, and invasion, even in the presence of EGF. It also induced apoptosis via the intrinsic pathway, likely through suppression of MMP-2/9 activity and downregulation of PI3K/AKT and MAPK signaling7. K. parviflora extract also reported to show potent anti-proliferation activities against HeLa cells6. It inhibited HL-60 cell growth and reduced cell viability in a manner dependent on both dose and exposure time9. Similarly, the methanol extracts have shown positive inhibitory effects against melanoma 4A5 cells13. Park et al., (2024) demonstrated that dichloromethane extract of K. parviflora showed strong inhibitory effects on human melanoma cell lines34. Similarly, K. parviflora anthocyanidins extract (300 mg/mL) decreased cell proliferation of ES-2 cells by 53.9% and 53.6% OV-9035. Moreover, K. parviflora extract (50 µg/mL) significantly inhibited colony formation of PANC-1 cells36. As reported by Thairat et al. (2022), K. parviflora extract showed no cytotoxic effects on normal oral keratinocytes (NOK) at concentrations up to 7.5 mg/mL, with cell viability Remaining above 75%. Also in HSC-4 cancer cells, no cytotoxicity was observed at concentrations up to 30 mg/mL. These findings provide insight into the safety and biological responses of both cell types to K. parviflora extract37. Another study provides substantial evidence that K. parviflora extract exhibits anticancer activity by disrupting growth and survival signaling pathways, reducing metalloproteinase-2 activity, inhibiting cell migration and invasion, and promoting apoptosis in HeLa cervical cancer cells6. There are studies on K. parviflora ethanol extract revealing cytotoxic activity with IC₅₀ values as 60.24 ± 1.73 µg/mL against KB cells and as 27.22 ± 1.04 µg/mL against NCI-H187 cells, indicating strong potential as an anticancer agent38. Our study is also in accordance with the above discussed reports showing substantial cytotoxic effects against tested cell lines. Very less reports are available on cytotoxicity of K. parviflora rhizome oil. There are few other cell lines as A431, HCT15, LN18, showing cytotoxic activity which is not yet reported against K. parviflora rhizome oil.

In our antimicrobial study, the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of the oil was found to range between 250 and 125 µg/ml for Class Bacilli organisms (S. aureus, S. epidermidis, and B. subtilis). A MIC 62.5 µg/ml was observed for the Class Gammaproteobacteria (K. pneumoniae) and the fungal strain C. albicans. The trend reversed in the case of E.coli where the highest concentration of about 500 µg/ml was unable to show any MIC. Further testing using the zone of inhibition method confirmed that the essential oil had no antimicrobial effect against E. coli. Mild activity was noted against B. subtilis, while moderate activity was observed against S. aureus and S. epidermidis. The highest antimicrobial activity was seen against K. pneumoniae and C. albicans (Table 3; Fig. 5). The activities are categorized as resistant if the zone of inhibition (ZOI) is less than 7 mm, intermediate if it ranges from 8 to 10 mm, and sensitive if it exceeds 11 mm39. Atom et al. (2022), studied the antibacterial potential of rhizome extract against Micrococcus luteus and the plant disease as Rhizoctonia solani using agar well diffusion method40. Several other reports available on the extracts of K. parviflora rhizomes demonstrate antimicrobial activity against a broad spectrum of pathogenic bacterial species as Streptococcus faecalis, Sihigella dysenteriae, Bacillus cereus, Staphylococcus aureus, Salmonella typhi, Candida tropicalis, Proteus vulgaris and Saccharomyces cerevisiae14. Some other reported ethanolic extract of K. parviflora rhizome showed potent anti-fungal activity against Microsporum gypseum, Trichophyton rubrum, and Trichophyton mentagrophytes13. The extract of K. parviflora has the potential to be an effective anti-biofilm agent against bacteria that cause caries and might be used in conjunction with other caries prevention techniques41. Study done by Leswara et al. (2024), found that ethanol extracts of K. parviflora rhizome exhibited strong antibacterial activity against S. aureus at concentrations of 25%, 50%, 75%, and 100%42. Endophyte extracts isolated from K. parviflora also showed notable antibacterial activity against S. aureus showing MIC as low as 64 µg/m43. However, in our study, we have taken S. aureus, B. subtilis, K. pneumoniae, S. epidermis, and C. albicans which showed effective antimicrobial activity. Accordingly, the findings indicate the potential of K. parviflora as a natural antibacterial agent and encourage its continued development for use in pharmaceutical applications.

The DPPH and ABTS experiment assessed the free radical scavenging activity of the rhizome oil. DPPH and ABTS, an in vitro free radical scavenging model, was used in the experimental methods, with ascorbic acid as reference and inhibition percentage was determined and represented by the IC50 value. The oil exhibited dose dependent DPPH and ABTS free radical scavenging activity. The IC50 value for DPPH and ABTS Assay was 0.50 ± 0.01 mg/ml and 0.40 ± 0.01 mg/ml respectively (Table 4). Other researchers have reported K. parviflora rhizome EO demonstrated antioxidant effect, showing DPPH radical scavenging activities as high as 80.90% and ABTS activity as 94.04% at a concentration of 10 mg/mL. They found IC50 values as 0.451 ± 0.051 mg/ml and 0.527 ± 0.22 mg/ml respectively31. Rehman et al. (2021), stated that the highest total phenolic content and antioxidant activity in callus cultures of K. parviflora44. The highest total flavonoid content found from K. parviflora ethanolic extract is 384.0 ± 3.01 mg QE g − 1 extracts and antioxidant activity is Reported as 369.21 ± 3.87 (ABTS assay) and 91.73 ± 1.47 (DPPH assay)45. Atom et al. (2022), investigated the plant extract that showed potent antioxidant activity of DPPH and ABTS with an IC50 value of 3.0 ± 0.1 mg/ml and 19.4 ± 1.2 µg/ml respectively40. As reported by Song et al. (2021), byproducts of K. parviflora are abundant in lipophilic antioxidants46. Another investigation reported Black ginger nanoparticles showed effective antimicrobial results against E. coli and P. aeruginosa. Also, the DPPH assay of rhizome extract showed 438.3 ± 2.52 µg/ml whereas black ginger AuNPs showed 94.5 ± 2.49 µg/ml47. The DPPH and ABTS potential activity was shown in rhizome extracts of K. parviflora48. The hexane extract of K. parviflora rhizomes produced four methoxyflavones, where 5-hydroxy-3,7-dimethoxyflavone exhibiting the highest antioxidant activity, showing 64.88% inhibition in the DPPH assay. It also demonstrated significant antibacterial effects against S. aureus and P. aeruginosa in other reports49. Another report investigated the antioxidant properties of K. parviflora rhizome extract exhibited a significant value of 8.47 ± 0.52 µM, while another compound showed value of 5.66 ± 0.26 µM at 10.0 µM50. The ethanol extract of K. parviflora showed highest phenolic and flavonoid content and strong antioxidant activity as IC₅₀: 0.161 mg/mL and found 5-hydroxy-3,7-dimethoxyflavone as a major compound as per other reports51. Suresh et al. (2025), reported the methanolic extract of black ginger showed the highest antioxidant activity among tested assays52. The highest DPPH activity was observed at 75% ethanol, while 25% ethanol gave the greatest FRAP value53. The compounds present in K. parviflora rhizomes have various promising biological and pharmaceutical activities as reported by Elshamy et al. (2019)54. With IC₅₀ values of 307 ± 3.41 µg/mL (ABTS) and 552 ± 2.89 µg/mL (DPPH), a 2025 study measured the high levels of phenolic (66.14 mg GAE/g) and flavonoid (57.18 mg QE/g) in K. parviflora ethanolic extracts, chemical classes linked to free radical neutralization and various antioxidant mechanisms with notable free radical scavenging in ABTS and DPPH assays, confirming pertinent antioxidant potential55. K. parviflora possesses notable antioxidant activity, primarily attributed to its rich concentration of flavonoids and methoxyflavones.

Conclusion

The study signifies the effectiveness of GC-TOF-MS for the complete volatile profiling of K. parviflora rhizome oil. Few compounds were stated for the first time in K. parviflora. The study revealed the selective cytotoxicity of rhizome oil only towards cancer cells. It also showed stronger inhibitory effects against bacterial and fungal strains as compared to standard control. Its antioxidant activity helps in reducing oxidative stress and protecting cellular health. Thus, this rhizome oil can serve as better natural antimicrobials and antioxidants. Also the findings suggest a new method to exploit K. parviflora in drug discovery. There is always an increased price value of its rhizome for which it can be exploited for commercial cultivation. Nevertheless, to our knowledge; there is a lack of reports on the identification of phytoconstituents from the GCxGC-TOF-MS analysis of K. parviflora rhizome essential oil. So, future studies should be done to focus on isolating the phytochemicals and understanding its various bioactivities. However, additional accompanying investigations in animal models are required to validate the bioactivities of K. parviflora in vivo.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

-

Pham, N. K., Nguyen, H. T. & Nguyen, Q. B. A review on the ethnomedicinal uses, phytochemistry, and Pharmacology of plant species belonging to the Kaempferia L. genus (Zingiberaceae). Pharm. Sci. Asia. 48 (1), 1–23 (2021).

-

Prabakaran, S., Saad, H. M., Tan, C. H., Abdul Rahman, S. & Sim, K. S. S. N. Investigation of phytochemical composition, radical scavenging potential, Anti-Obesogenic effects, and Anti-Diabetic activities of Kaempferia parviflora rhizomes. Chem Biodiversity 22, (1).https://doi.org/10.1002/cbdv.202401086 (2025).

-

Yenjai, C., Prasanphen, K., Daodee, S., Wongpanich, V. & Kittakoop, P. Bioactive flavonoids from Kaempferia parviflora. Fitoterapia 75 (1), 89–92 (2004).

-

Sae-Wong, C. et al. Suppressive effects of methoxyflavonoids isolated from Kaempferia parviflora on inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) expression in RAW 264.7 cells. J. Ethnopharmacol. 136, 488–495 (2011).

-

Tan, T. Y. C. et al. Application of Kaempferia parviflora: A perspective review. Nat. Prod. Commun. 19 (10), 1–20 (2024).

-

Potikanond, S. et al. Kaempferia parviflora extract exhibits Anti-cancer activity against HeLa cervical cancer cells. Front. Pharmacol. 8, 630 (2017).

-

Paramee, S. et al. Anti-Cancer effects of Kaempferia parviflora on ovarian cancer SKOV3 cells. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 12, 12 (2018).

-

Banjerdpongchai, R., Suwannachot, K., Rattanapanone, V. & Sripanidkulchai, B. Ethanolic rhizome Ex.ract from Kaempferia parviflora wall. Ex. Baker induces apoptosis in HL-60 cells. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 9, 595–600 (2008).

-

Banjerdpongchai, R., Chanwikruy, Y., Rattanapanone, V. & Sripanidkulchai, B. Induction of apoptosis in the human leukemic U937 cell line by Kaempferia parviflora wall.ex.baker extract and effects of Paclitaxel and camptothecin. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 10, 1137–1140 (2009).

-

Leardkamolkarn, V., Tiamyuyen, S. & Sripanidkulchai, B. O. Pharmacological activity of Kaempferia parviflora extract against human bile duct cancer cell lines. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 10, 695–698 (2009).

-

Patanasethanont, D. et al. Modulation of function of multidrug resistance associated-proteins by Kaempferia parviflora extracts and their components. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 566, 67–74 (2007).

-

Ninomiya, K. et al. Simultaneous quantitative analysis of 12 methoxyflavones with melanogenesis inhibitory activity from the rhizomes of Kaempferia parviflora. J. Nat. Med. 70, 179–189 (2016).

-

Kummee, S., Tewtrakul, S. & Subhadhirasakul, S. Antimicrobial activity of the ethanol extract and compounds from the rhizomes of Kaempferia parviflora. Songklanakarin J. Sci. Technol. 30 (4), 463–466 (2008).

-

Butkhup, L. & Samappito, S. Vitro free radical scavenging and antimicrobial activity of some selected Thai medicinal plants. Res. J. Med. Plants. 5 (3), 254–265 (2011).

-

Anh Van, C., Duc, D. X. & Son, N. T. Kaempferia diterpenoids and flavonoids: an overview on phytochemistry, biosynthesis, synthesis, pharmacology, and pharmacokinetics. Med. Chem. Res. 33, 1–20 (2024).

-

Rajeswary, M. et al. Zingiber cernuum (Zingiberaceae) essential oil as effective larvicide and oviposition deterrent on six mosquito vectors, with little non-target toxicity on four aquatic mosquito predators. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. Int. 25 (11), 10307–10316 (2018).

-

Thawtar, M. S. et al. K. N. Exploring volatile organic compounds in rhizomes and leaves of Kaempferia parviflora wall. Ex Baker using HS-SPME and GC–TOF/MS combined with multivariate analysis. Metabolites 13 (5), 651 (2023).

-

MTT Cell Proliferation Assay Instruction Guide. – ATCC, VA, USA www.atcc.org.

-

Gerlier, D. & Thomasset, N. Use of MTT colorimetric assay to measure cell activation. J. Immunol. Methods. 94 (1–2), 57–63 (1986).

-

Blessy, R. et al. Antibacterial activity of an endangered medicinal plant Anaphyllum Wightii schott. Leaves. Cross Res. 13 (2), 181–187 (2022).

-

Orhan, D. D. et al. Antibacterial, antifungal, and antiviral activities of some flavonoids. Microbiol. Res. 165, 496–504 (2010).

-

Varsha, K. K. et al. Antifungal, anticancer, and aminopeptidase inhibitory potential of a phenazine compound produced by Lactococcus BSN307. Indian J. Microbiol. 56, 411–416 (2016).

-

Jena, S. et al. Chemical composition and antioxidant activity of essential oil from leaves and rhizomes of Curcuma angustifolia Roxb. Nat. Prod. Res. 31 (18), 2188–2191 (2017).

-

Re, R. et al. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radic Biol. Med. 26, 1231–1237 (1999).

-

Feng, Y. et al. Essential oils and nutrients constitutes of Kaempferia parviflora rhizome and the activities against plant pathogens. J. South. Agric. 54 (7), 2081–2091 (2023).

-

Begum, T. et al. Direct sunlight and partial shading alter the quality, quantity, biochemical activities of Kaempferia parviflora wall., ex Baker rhizome essential oil: A high industrially important species. Ind. Crops Prod. 180, 114765 (2022).

-

Pitakpawasutthi, Y., Palanuvej, C. & Ruangrungsi, N. Quality evaluation of Kaempferia parviflora rhizome with reference to 5,7-dimethoxyflavone. J. Adv. Pharm. Technol. Res. 9 (1), 26–31 (2018).

-

Wongpia, A. et al. Chemical composition analysis of essential oil from black gingers (Kaempferia parviflora) by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS). Acta Hortic. 1339, 323–330 (2022).

-

Pripdeevech, P. et al. Adaptogenic-active components from Kaempferia parviflora rhizomes. Food Chem. 132 (3), 1150–1155 (2012).

-

Wungsintaweekul, J., Sitthithaworn, W., Putalun, W., Pfeifhoffer, H. W. & Brantner, A. Antimicrobial, antioxidant activities and chemical composition of selected Thai spices. Songklanakarin J. Sci. Tech. 32 (6), 589 (2010).

-

Nguyen, D. M. C., Luong, T. H., Nghiem, T. C. & Jung, W. J. Chemical composition, antioxidant and antifungal activities of rhizome essential oil of Kaempferia parviflora wall. Ex Baker grown in Vietnam. J. Appl. Biol. Chem. 66 (3), 15–22 (2023).

-

Vaishnavi, B. A. et al. Variation in the volatile oil composition and antioxidant activity of zingiberaceae: A comparative investigation. Annals Phytomed. 13 (1), 1008–1018 (2024).

-

Hairunisa, I., Abu Bakar, M. F. & Da’i, M. Pharmacological and anticancer potential of black ginger (Kaempferia parviflora) – Review Article. Iraqi J. Pharm. Sci. 33 (4), 30–48 (2024).

-

Park, G. S. et al. Evaluating the diverse anticancer effects of Laos Kaempferia parviflora (Black Ginger) on human melanoma cell lines. Med. (Kaunas Lithuania). 60 (8), 1371 (2024).

-

Kim, M. H., Park, S., Song, G., Lim, W. & Han, Y. S. Antigrowth effects of Kaempferia parviflora extract enriched in anthocyanidins on human ovarian cancer cells through Ca2+–ROS overload and mitochondrial dysfunction. Mol. Cell. Toxicol. 18, 383–391 (2022).

-

Sun, S. et al. Anti-Austerity Activity of Thai Medicinal Plants: Chemical Constituents and Anti-Pancreatic Cancer Activities of Kaempferia parviflora. Plants. 10, 229 (2021).

-

Thairat, S., Srichan, R. & Mala, S. Cytotoxic effect of Kaempferia parviflora extract on normal oral keratinocytes and a human squamous carcinoma cell line. M Dent. J. 42 (1), 33–38 (2022).

-

Parkpoom, T., Suksabye, P., Parkpoom, P., Chantree, K. & Thummamikkapong, S. Antioxidant and cytotoxic activities of Thai local plant extracts. SWU J. Sci. Tech. 16 (31), 1–16 (2024).

-

Kohner, P. C., Rosenblatt, J. E. & Cockerill, F. R. Comparison of agar dilution, broth dilution, and disk diffusion testing of ampicillin against Haemophilus spp. Using in-house and commercially prepared media. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32, 1594–1596 (1994).

-

Atom, R. S. et al. GC-MS profiling, in vitro antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of Kaempferia parviflora wall. Ex. Baker rhizome Ex.ract. Int. J. Pharm. Invest. 12 (4), 430–437 (2022).

-

Mala, S. et al. Effect of Kaempferia parviflora on Streptococcus mutans biofilm formation and its cytotoxicity. Key Eng. Mater. 773, 328–332 (2018).

-

Leswara, D. F. & Larasati, D. Antibacterial potential of Kaempferia parviflora rhizome extract against Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923. J. Food Pharm. Sci. 12 (3), 235–240 (2024).

-

Praptiwi, P. et al. Bioactivity evaluation of compounds produced by Fusarium equiseti from Kaempferia parviflora rhizome from Indonesia. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 15 (7), 179–192 (2025).

-

Rahman, Z. A., Othman, A. N., Machap, C. A., Amran, B. A. & Basiron, N. N. A. Total phenolic content and antioxidant activities in callus of Kaempferia parviflora. Int. J. Res. 9 (6), 77–84 (2021).

-

Panyakaew, J. et al. Kaempferia sp. extracts as UV protecting and antioxidant agents in sunscreen. J. Herbs Med. Plants. 27 (1), 37–56 (2020).

-

Song, K., Saini, R. K., Keum, Y. S. & Sivanesan, I. Analysis of lipophilic antioxidants in the leaves of Kaempferia parviflora wall. Ex Baker using LC–MRM–MS and GC–FID/MS. Antioxidants 10 (1573), 1–14 (2021).

-

Varghese, B. A. et al. Green synthesis of gold nanoparticles using Kaempferia parviflora rhizome extract and their characterization and application as antimicrobial, antioxidant, and catalytic degradation agents. J. Taiwan. Inst. Chem. Eng. 126, 166–172 (2021).

-

Choi, M. H., Kim, K. H. & Yook, H. S. Antioxidant activity and development of cosmetic materials of solvent extracts from Kaempferia parviflora. J. Korean Soc. Food Sci. Nutr. 47 (4), 414–421 (2018).

-

Wongcharu, A. et al. Chemical constituents of black Galingale rhizome from hexane crude extract and its nanoemulsion Preparation. Adv. Sci. Tech. 155, 25–30 (2024).

-

Nguyen, P. T., Bui, T. T. L., Lee, S. H., Jang, H. D. & Young, H. K. Anti-osteoporotic and antioxidant activities by rhizomes of Kaempferia parviflora wall. Ex Baker. Nat. Prod. Sci. 22 (1), 13–19 (2016).

-

Aidiel, M. et al. Enhancing the total polyphenol content and antioxidant activity of Kaempferia parviflora through optimized binary solvent extraction: isolation and characterization of major PMF metabolite. Malaysian J. Chem. 26 (6), 106–120 (2024).

-

Suresh, H. et al. Profiling of metabolites and minerals from black ginger and blue turmeric rhizomes by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry analysis and their biopotentials. J Food Sci. Tech https://doi.org/10.1007/s13197-024-06176-w(2025).

-

Chaisuwan, V., Dajanta, K. & Srikaeo, K. Effects of extraction methods on antioxidants and methoxyflavones of Kaempferia parviflora. Food Res. 6 (3), 374–381 (2022).

-

Elshamy, A. I. et al. Recent advances in Kaempferia phytochemistry and biological activity: A comprehensive review. Nutrients 11 (10), 2396 (2019).

-

Takomthong, P. et al. Kaempferia parviflora extract and its methoxyflavones as potential anti-Alzheimer assessing in vitro, integrated computational approach, and in vivo impact on behaviour in scopolamine-induced amnesic mice. PloS One. 20 (3), e0316888 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Prof (Dr.) M.R. Nayak, President, Siksha O Anusandhan University for providing facilities and encouraging throughout. We sincerely thank Two Dimensional Gas Chromatograph with Time of Flight Mass Spectrometer, Central facility, IIT Bombay for providing sample analysis data of the present report.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Siksha ‘O’ Anusandhan (Deemed To Be University). Open access funding provided by Siksha O Anusandhan (Deemed to be University). This study received no specific grant from any funding agency.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Panigrahi, R., Sahoo, S.R., Dash, B. et al. Metabolic profile and bioactivity of the rhizome oil of Kaempferia parviflora from Eastern India. Sci Rep 15, 38674 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19296-w

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

Version of record:

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19296-w