Data availability

TCGA pan-cancer data were downloaded from UCSC Xena (http://xena.ucsc.edu/). Survival associations of target genes were evaluated using RNA-seq data obtained from PCaDB (http://bioinfo.jialab-ucr.org/PCaDB/). Additional analysis used bulk RNA-seq data from several studies, including CPGEA73, EBM2015 (ref. 74) and NGS-ProToCol75.

The raw screen data and the 22Rv1 shRNA knockdown CHD9 RNA-seq, ChIP-seq and ATAC-seq datasets were deposited to the Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number GSE242447. The MS proteomics data were deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium through the PRIDE76 partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD072235. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The code for epitranscriptomic screening analysis and data processing is publicly available on GitHub (https://github.com/HansenHeLab/m6a-crispr-casRx-publish). Processed data and associated resources were are available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.18009931 (ref. 77).

References

-

Wang, X. et al. N6-methyladenosine modulates messenger RNA translation efficiency. Cell 161, 1388–1399 (2015).

-

Xiao, W. et al. Nuclear m6A reader YTHDC1 regulates mRNA splicing. Mol. Cell 61, 507–519 (2016).

-

Wang, X. et al. N6-methyladenosine-dependent regulation of messenger RNA stability. Nature 505, 117–120 (2014).

-

Liu, J. et al. A METTL3–METTL14 complex mediates mammalian nuclear RNA N6-adenosine methylation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 10, 93–95 (2014).

-

Jia, G. et al. N6-methyladenosine in nuclear RNA is a major substrate of the obesity-associated FTO. Nat. Chem. Biol. 7, 885–887 (2011).

-

Zheng, G. et al. ALKBH5 is a mammalian RNA demethylase that impacts RNA metabolism and mouse fertility. Mol. Cell 49, 18–29 (2013).

-

Roundtree, I. A., Evans, M. E., Pan, T. & He, C. Dynamic RNA modifications in gene expression regulation. Cell 169, 1187–1200 (2017).

-

Shi, H. et al. YTHDF3 facilitates translation and decay of N6-methyladenosine-modified RNA. Cell Res. 27, 315–328 (2017).

-

Wei, J. et al. FTO mediates LINE1 m6A demethylation and chromatin regulation in mESCs and mouse development. Science 376, 968–973 (2022).

-

Li, H.-B. et al. m6A mRNA methylation controls T cell homeostasis by targeting the IL-7/STAT5/SOCS pathways. Nature 548, 338–342 (2017).

-

Choe, J. et al. mRNA circularization by METTL3–eIF3h enhances translation and promotes oncogenesis. Nature 561, 556–560 (2018).

-

Zhang, S. et al. m6A demethylase ALKBH5 maintains tumorigenicity of glioblastoma stem-like cells by sustaining FOXM1 expression and cell proliferation program. Cancer Cell 31, 591–606 (2017).

-

Wang, S. et al. N6-methyladenosine reader YTHDF1 promotes ARHGEF2 translation and RhoA signaling in colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology 162, 1183–1196 (2022).

-

Chang, G. et al. YTHDF3 induces the translation of m6A-enriched gene transcripts to promote breast cancer brain metastasis. Cancer Cell 38, 857–871 (2020).

-

Wang, W. et al. METTL3 promotes tumour development by decreasing APC expression mediated by APC mRNA N6-methyladenosine-dependent YTHDF binding. Nat. Commun. 12, 3803 (2021).

-

Shi, Y. et al. YTHDF1 links hypoxia adaptation and non-small cell lung cancer progression. Nat. Commun. 10, 4892 (2019).

-

Hart, T. et al. High-resolution CRISPR screens reveal fitness genes and genotype-specific cancer liabilities. Cell 163, 1515–1526 (2015).

-

Schmidt, R. et al. CRISPR activation and interference screens decode stimulation responses in primary human T cells. Science 375, eabj4008 (2022).

-

Nuñez, J. K. et al. Genome-wide programmable transcriptional memory by CRISPR-based epigenome editing. Cell 184, 2503–2519 (2021).

-

Coelho, M. A. et al. Base editing screens define the genetic landscape of cancer drug resistance mechanisms. Nat. Genet. 56, 2479–2492 (2024).

-

Niu, X. et al. Prime editor-based high-throughput screening reveals functional synonymous mutations in human cells. Nat. Biotechnol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-025-02710-z (2025).

-

Cox, D. B. T. et al. RNA editing with CRISPR–Cas13. Science 358, 1019–1027 (2017).

-

Konermann, S. et al. Transcriptome engineering with RNA-targeting type VI-D CRISPR effectors. Cell 173, 665–676 (2018).

-

Abudayyeh, O. O. et al. RNA targeting with CRISPR–Cas13. Nature 550, 280–284 (2017).

-

Li, S. et al. Screening for functional circular RNAs using the CRISPR–Cas13 system. Nat. Methods 18, 51–59 (2021).

-

Wilson, C., Chen, P. J., Miao, Z. & Liu, D. R. Programmable m6A modification of cellular RNAs with a Cas13-directed methyltransferase. Nat. Biotechnol. 38, 1431–1440 (2020).

-

Xia, Z. et al. Epitranscriptomic editing of the RNA N6-methyladenosine modification by dCasRx conjugated methyltransferase and demethylase. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, 7361–7374 (2021).

-

Luo, X. et al. RMVar: an updated database of functional variants involved in RNA modifications. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, D1405–D1412 (2021).

-

Xu, X. et al. The landscape of N6-methyladenosine in localized primary prostate cancer. Nat. Genet. 57, 934–948 (2025).

-

Wang, S. et al. The N6-methyladenosine epitranscriptomic landscape of lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Discov. 14, 2279–2299 (2024).

-

Meyer, K. D. et al. Comprehensive analysis of mRNA methylation reveals enrichment in 3′ UTRs and near stop codons. Cell 149, 1635–1646 (2012).

-

Dominissini, D. et al. Topology of the human and mouse m6A RNA methylomes revealed by m6A-seq. Nature 485, 201–206 (2012).

-

Chen, S. et al. Widespread and functional RNA circularization in localized prostate cancer. Cell 176, 831–843 (2019).

-

Wessels, H.-H. et al. Massively parallel Cas13 screens reveal principles for guide RNA design. Nat. Biotechnol. 38, 722–727 (2020).

-

Narla, G. et al. KLF6, a candidate tumor suppressor gene mutated in prostate cancer. Science 294, 2563–2566 (2001).

-

Guo, Y., Yu, Q., Ke, M. & Wang, J. PRR7 could serve as a prognostic biomarker for prostate cancer patients. Asian J. Surg. 46, 5133–5135 (2023).

-

Zhang, X. et al. Eukaryotic elongation factor 2 (eEF2) is a potential biomarker of prostate cancer. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 24, 885–890 (2018).

-

Clapier, C. R., Iwasa, J., Cairns, B. R. & Peterson, C. L. Mechanisms of action and regulation of ATP-dependent chromatin-remodelling complexes. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 18, 407–422 (2017).

-

Yoo, H. et al. ATP-dependent chromatin remodeler CHD9 controls the proliferation of embryonic stem cells in a cell culture condition-dependent manner. Biology 9, 428 (2020).

-

Xu, L. et al. Decreased expression of chromodomain helicase DNA-binding protein 9 is a novel independent prognostic biomarker for colorectal cancer. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 51, e7588 (2018).

-

Song, D., Zhang, Q., Zhang, H., Zhan, L. & Sun, X. MiR-130b-3p promotes colorectal cancer progression by targeting CHD9. Cell Cycle 21, 585–601 (2022).

-

Lasorsa, V. A. et al. Exome and deep sequencing of clinically aggressive neuroblastoma reveal somatic mutations that affect key pathways involved in cancer progression. Oncotarget 7, 21840–21852 (2016).

-

Fan, R. et al. A combined deep learning framework for mammalian m6A site prediction. Cell Genom. 4, 100697 (2024).

-

Zhang, Y. et al. Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS). Genome Biol. 9, R137 (2008).

-

Wang, S. et al. Target analysis by integration of transcriptome and ChIP-seq data with BETA. Nat. Protoc. 8, 2502–2515 (2013).

-

Karimian, A., Ahmadi, Y. & Yousefi, B. Multiple functions of p21 in cell cycle, apoptosis and transcriptional regulation after DNA damage. DNA Repair 42, 63–71 (2016).

-

Liu, C.-J. et al. GSCALite: a web server for gene set cancer analysis. Bioinformatics 34, 3771–3772 (2018).

-

Liu, C.-J. et al. GSCA: an integrated platform for gene set cancer analysis at genomic, pharmacogenomic and immunogenomic levels. Brief. Bioinform. 24, bbac558 (2023).

-

Li, P. et al. ELK1-mediated YTHDF1 drives prostate cancer progression by facilitating the translation of Polo-like kinase 1 in an m6A dependent manner. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 18, 6145–6162 (2022).

-

Pi, J. et al. YTHDF1 promotes gastric carcinogenesis by controlling translation of FZD7. Cancer Res. 81, 2651–2665 (2021).

-

Liu, T. et al. The m6A reader YTHDF1 promotes ovarian cancer progression via augmenting EIF3C translation. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, 3816–3831 (2020).

-

Han, B. et al. YTHDF1-mediated translation amplifies Wnt-driven intestinal stemness. EMBO Rep. 21, e49229 (2020).

-

Zaccara, S. & Jaffrey, S. R. A unified model for the function of YTHDF proteins in regulating m6A-modified mRNA. Cell 181, 1582–1595 (2020).

-

Micaelli, M. et al. Small-molecule ebselen binds to YTHDF proteins interfering with the recognition of N6-methyladenosine-modified RNAs. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci 5, 872–891 (2022).

-

Mori, S. et al. Myb-binding protein 1A (MYBBP1A) is essential for early embryonic development, controls cell cycle and mitosis, and acts as a tumor suppressor. PLoS ONE 7, e39723 (2012).

-

Li, Z. et al. Intrinsic targeting of host RNA by Cas13 constrains its utility. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 8, 177–192 (2024).

-

Konermann, S. et al. Genome-scale transcriptional activation by an engineered CRISPR–Cas9 complex. Nature 517, 583–588 (2015).

-

Dobin, A. et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21 (2013).

-

Cui, X., Meng, J., Zhang, S., Chen, Y. & Huang, Y. A novel algorithm for calling mRNA m6A peaks by modeling biological variances in MeRIP-seq data. Bioinformatics 32, i378–i385 (2016).

-

Linder, B. et al. Single-nucleotide-resolution mapping of m6A and m6Am throughout the transcriptome. Nat. Methods 12, 767–772 (2015).

-

Meyer, K. D. DART-seq: an antibody-free method for global m6A detection. Nat. Methods 16, 1275–1280 (2019).

-

Koh, C. W. Q., Goh, Y. T. & Goh, W. S. S. Atlas of quantitative single-base-resolution N6-methyl-adenine methylomes. Nat. Commun. 10, 5636 (2019).

-

Chen, H.-X., Zhang, Z., Ma, D.-Z., Chen, L.-Q. & Luo, G.-Z. Mapping single-nucleotide m6A by m6A-REF-seq. Methods 203, 392–398 (2022).

-

Chen, K. et al. High-resolution N6-methyladenosine (m6A) map using photo-crosslinking-assisted m6A sequencing. Angew. Chem. 127, 1607–1610 (2015).

-

Shu, X., Cao, J. & Liu, J. m6A-label-seq: a metabolic labeling protocol to detect transcriptome-wide mRNA N6-methyladenosine (m6A) at base resolution. STAR Protoc 3, 101096 (2022).

-

Pagès, H. Package ‘BSgenome’. Bioconductor http://bioconductor.statistik.tu-dortmund.de/packages/3.1/bioc/manuals/BSgenome/man/BSgenome.pdf (2015).

-

Li, W. et al. MAGeCK enables robust identification of essential genes from genome-scale CRISPR/Cas9 knockout screens. Genome Biol. 15, 554 (2014).

-

Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9, 357–359 (2012).

-

Li, H. et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078–2079 (2009).

-

Tarasov, A., Vilella, A. J., Cuppen, E., Nijman, I. J. & Prins, P. Sambamba: fast processing of NGS alignment formats. Bioinformatics 31, 2032–2034 (2015).

-

Yu, G., Wang, L.-G. & He, Q.-Y. ChIPseeker: an R/Bioconductor package for ChIP peak annotation, comparison and visualization. Bioinformatics 31, 2382–2383 (2015).

-

Xu, X., Wang, Y. & Lam, M. Functional mapping of m6A RNA modifications in cancer. protocols.io https://doi.org/10.17504/protocols.io.5jyl8xnr7v2w/v1 (2025).

-

Li, J. et al. A genomic and epigenomic atlas of prostate cancer in Asian populations. Nature 580, 93–99 (2020).

-

Ross-Adams, H. et al. Integration of copy number and transcriptomics provides risk stratification in prostate cancer: a discovery and validation cohort study. EBioMedicine 2, 1133–1144 (2015).

-

Hendriksen, P. J. M. et al. Evolution of the androgen receptor pathway during progression of prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 66, 5012–5020 (2006).

-

Perez-Riverol, Y. et al. The PRIDE database at 20 years: 2025 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 53, D543–D553 (2025).

-

Zhu, H. HansenHeLab/m6a-CRISPR-casRx-publish: m6a-CRISPR-casRx-guide-design-Zenodo. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.18009931 (2025).

-

Taylor, B. S. et al. Integrative genomic profiling of human prostate cancer. Cancer Cell 18, P11–22 (2010).

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to the Q. Xie laboratory at Westlake University for discussion and technical support on RNA epitranscriptomic editing tools. We also thank the Princess Margaret Genomic Center, the UHN Animal Research Center, the Princess Margaret Hospital’s Drug Development Program Histo-Biomarker Laboratory, the SickKids UHN Flow Cytometry Facility and the SickKids SPARC BioCenter for their support in research assays. This work was supported by the Princess Margaret Cancer Foundation (0211920009 to H.H.H.), Canadian Cancer Society (TAG2018-2061), Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) operating grants (142246, 152863, 152864 and 159567 to H.H.H.) and Terry Fox New Frontiers Program Project Grant (PPG19-1090 and PPG23-1124 to H.H.H.). H.H.H. holds a tier 1 Canada research chair in RNA medicine. Xin Xu was supported by the Prostate Cancer Foundation Young Investigator Award (21YOUN06). H.Z. was supported by a CIHR doctoral award. Y.L. was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31801111), Dream Mentor Outstanding Young Talents Program of Shanghai Pulmonary Hospital (program no. fkyq1910), 2021 Shanghai ‘Medical Garden Rising Stars’ Young Medical Talents of Shanghai Municipal Health Commission Award (talent plan no. 202208-2274) and Shanghai Pujiang Program (program no. 22PJD063). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Cancer thanks Jianjun Chen, Jindan Yu and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

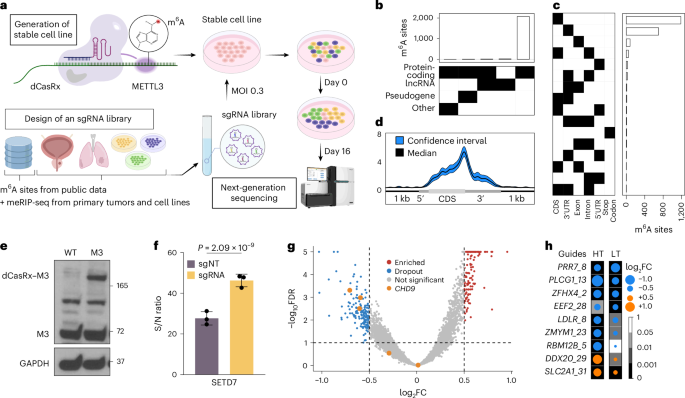

Extended Data Fig. 1 Design and characteristics of the sgRNA library.

a) A schematic of the library design process. b-e) Distribution of characteristics of m6A sites used for targeting guide design: the number of studies (b), the number of samples (c), the number of techniques (d) and the number of tissues (e) where an m6A site was found. f) Number of m6A sites captured by each of the six single base pair m6A detection experimental techniques. g) and h) Validation of m6A sites used for targeting guide design using meRIP-sequencing in primary lung adenocarcinoma (g) and primary prostate adenocarcinoma (h) samples. The median m6A site was identified in 59 lung samples and 118 prostate samples. i) Distribution of m6A sites used for targeting guide design overlapping with m6A peaks identified using meRIP-sequencing in cancer cell lines. j) Whether targeted m6A was associated with clinical outcome; biochemical relapse in a cohort of primary prostate adenocarcinoma patients and cancer associated death in a cohort of primary lung adenocarcinoma patients k) Mapping statistics of targeting and control guide RNAs to the human reference genome (hg38) using STAR. For targeting guide RNAs and targeting controls, only guides that exhibit unique genomic alignments were prioritized. For Nontargeting controls, only guides that were unmapped to the human reference genome were retained.

Extended Data Fig. 2 The quality control of the pooled library and the screen result.

a) m6A peak profiles along SETD7 transcripts from meRIP-Seq in multiple prostate and lung cancer cell lines, targeted peak boxed in red. b-c) Gini index of sgRNAs read evenness (b) and mapping rate (c) in pooled plasmid libraries. d) Spearman correlation of normalized counts in the 22Rv1 screen (T0_rep1-3 and T16 (T16_rep1-3); all pairwise r > 0.8, with stronger clustering observed within the T0 and T16 groups. e-f) Gini index (e) and mapping rate (f) for screen samples at T0 and T16 (3 replicates each). g) CDF plot of guide-level negative scores for sample-targeting (orange) vs non-targeting controls (blue). h) Volcano plot showing differentially expressed genes in 22Rv1. Vertical dashed lines indicate the -log2(1.2) and log2(1.2); the horizontal dashed line marks the P = 0.05. i) Western blot of dCasRx-M3 and endogenous METTL3 in H358, H2122, H1299, and LNCaP. GAPDH as a loading control. Representative of two independent experiments with similar results. j) m6A meRIP-qPCR quantification of SETD7 writing efficiency in four cell lines. Results were mean ± SD; n = three independent experiments. Fold change values of gSETD7 relative to gNT mean value were shown. Statistical significance was evaluated using an unpaired two-sided Student’s t-test. k) CDF of guide-level negative scores in H358 (Sample-targeting, orange; non-targeting, blue). l) Volcano plots of enriched or depleted guides in H358 cells. Vertical dashed lines represent log2 fold change -0.5 and 0.5; the horizontal dashed line marks an FDR threshold of 0.1. m) Volcano plots of differentially expressed genes (average |FC | > log2(1.2), P value < 0.05) in H358 after pooled screening. Vertical dashed lines indicate -log2(1.2) and log2(1.2); the horizontal dashed line marks adjusted P = 0.05.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Characteristics of enriched and depleted m6A sites and guides.

a, b) Overlap of significantly depleted (a) or enriched (b) sgRNAs identified in 22Rv1 and H358 m6A screens. Numbers indicate sgRNA counts, and two-sided Fisher’s exact test P values were shown. c, d) Gene level classification of enriched (right) and depleted (middle) m6A sites (c). Contingency table and χ-squared test summarizing the number of sites associated with each gene type (d). Sites may map to multiple components, indicated by covariate shown in black. e) and f) Gene component localization of enriched (right) and depleted (middle) m6A sites (e). Contingency table and χ-squared test showing the number of sites per gene component (f). Sites may map to multiple components, indicated by covariate shown in black. g) Metagene distribution of enriched, depleted and non-significant m6A sites. Solid lines indicate central tendency, and shaded bands represent 95% confidence intervals (2.5th-97.5th percentiles) from bootstrapped sampling. h) Proportion of enriched, depleted, and non-significant guides started at each position relative to the target m6A site. Each site was targeted from -30 bp to + 30 bp (32 guides total). i) Nucleotide composition at each position of a 30-bp guide design for enriched, depleted, and non-significant guides; purines (purple) and pyrimidines (blue) are indicated. j, k) Scatter plot comparing m6A screen effects (logFC) with CRISPR (j) or RNAi (k) gene scores from DepMap dataset. Each dot represents one gene, with enriched (orange), dropout (blue), and non-significant (gray) hits shown. Dashed line marks zero effect; Spearman correlation (two-sided) P values were shown. l-m) Overlap of significant genes identified in the m6A screen and CRISPR (l) or RNAi (m) dataset in 22Rv1. Gene counts and two-sided Fisher’s exact test P values were shown.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Clinical relevance of CHD9.

a) Comparison of CHD9 mRNA abundance between normal and tumor tissues across various cancer types in the TCGA dataset. b-d) Comparison of CHD9 mRNA abundance among normal, primary and metastatic prostate cancer samples across independent cohorts. e) CHD9 mRNA abundance in Ebm2015 cohort, comparing normal and tumor samples. For a-e), data are presented as box plots showing the median (center line), interquartile range (box), and whiskers extending to 1.5x the interquartile range. Sample sizes (n; tumor samples) are indicated in the figures. P values were calculated using two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum tests. f) Kaplan-Meier survival curves showing the survival probability grouped by median CHD9 mRNA abundance in the Ebm2015 cohort. P values were calculated using logrank test. g) Forest plot showing the association between CHD9 mRNA abundance and survival in different datasets. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals were derived from Cox proportional hazards regression, with two-sided Wald tests P values. Each point represents the HR, and horizontal error bars indicate the corresponding 95% confidence interval. N denotes the number of patients in each cohort. h) Comparison of the CHD9 average optical density between the normal (n = 105) and tumor (n = 105) samples from a tissue microarray. Differences between the two groups were evaluated using a two-sided Mann-Whitney U test. Data were summarized as box plots, in which the box spans the interquartile range (25th and 75th percentiles) and the center line denotes the median. Whiskers extend to 1.5x the interquartile range. Fold change values were presented as the ratio of tumor to normal mean. i) Representative IHC images of CHD9 staining in normal and tumor tissues. Magnified insets highlight selected regions. Scale bars, 100 μm.

Extended Data Fig. 5 CHD9 suppresses prostate cancer in vitro and in vivo.

Unless otherwise indicated, data are presented as mean ± SD from independent experiments (n as specified in each panel). a, b) Knockdown efficiency of CHD9-targeting in 22Rv1 cells, assessed by qPCR (a) n = 3; one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s test. and western blot (b). Representative of two independent experiments with similar results. c) Tumor weight (left) and tumor size (right) of xenografts derived from 22Rv1 cells expressing control (shGFP) or CHD9-targeting shRNAs. n = five mice; one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s test. d-e) CHD9 mRNA (d) and protein (e) abundance following shRNA-mediated knockdown in 22Rv1 cells (sh3, sh4). n = 3; one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s test. Representative of two independent experiments with similar results. f) Cell proliferation curves after CHD9 knockdown. n = 3; two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s test. g, h) Xenograft tumor growth curves (g) and endpoint tumor weights (h) of 22Rv1 cells expressing shG, sh3, or sh4. Data were mean ± SEM; n = ten mice; two-way (g) or one-way (h) ANOVA with Dunnett’s test. i-l) Knockdown efficiency of CHD9 in DU145 (i) and PC-3 (j) cells (Representative of two independent experiments with similar results), and corresponding effects on cell growth (k–l). n = 3; two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s test. m, n) Colony formation assays and quantification in DU145 (m) and PC-3 (n) cells expressing control or CHD9-targeting shRNAs. n = 3; one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s test. o-r) Migration and invasion assay following CHD9 knockdown in DU145 (o, q) and PC-3 (p, r) cells. Representative images and quantification are shown. n = 3; two-way ANOVA. Scale bar, 200 μm. s-t) Effects of CHD9 depletion on cell growth in NCI-H358 (s) and A549 (t). n = 3; two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s test. u, v) Relative CHD9 mRNA abundance (u) and m6A modification levels at selected CHD9 sites measured by RT-qPCR and SELECT assays (v) in 22Rv1 and H358. n = 3; two-sided unpaired t-tests with Welch’s correction.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Site-specific m6A editing validates functional regulation of CHD9.

Unless otherwise indicated, data are presented as mean ± SD from independent experiments (n as specified in each panel). a) Writing efficiency evaluated by m6A meRIP-qPCR in 22Rv1 cells. n = 3; one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s test. b) CHD9 abundance after dCasRx-M3-based m6A writing in 22Rv1 cells detected by western blot. Representative of two independent experiments with similar results. c) DeepSRAMP prediction of candidate m6A sites within CHD9 mRNA. The x-axis represents nucleotide position, and the y-axis indicates predicted m6A probability scores (0-1). Five sites within the targeted peak are highlighted in red. d) SELECT-based quantification of m6A abundance at predicted sites in 22Rv1 cells after dCasRx-M3 editing. n = 3; two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s test. e) Relative m6A abundance at the CHD9 A8466 site measured by SELECT assay in 22Rv1 cells transfected with non-targeting control (sgNT) or five CHD9-targeting guide RNAs (g1-g5). n = 3; one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s test. f, g) Cell proliferation (f) and relative m6A abundance at the CHD9 A8466 site (g) in 22Rv1 cells transfected with the dCasRx-M3 guided by CHD9-targeting guides (sg6, sg7) or sgNT. n = 3; two-way (f) or one-way (g) ANOVA with Dunnett’s test. h-i) Representative images of migration and invasion assay (h) and the quantification (i) after writing CHD9 in 22Rv1 cells. n = 3; two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s test. Scale bar, 200 μm. j) Tumor weight (left) and tumor size (right) of xenografts derived from 22Rv1-M3 cells after writing CHD9 by CHD9-targeting sgRNAs. n = ten mice; one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s test. k-l) Western blot showing CHD9 protein abundance (k; representative of two independent experiments with similar results) and cell proliferation analysis (l) in 22Rv1 cells after dCasRx-ALKBH5-mediated m6A erasing at CHD9. n = 3; two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s test. m, n) Representative images (m) and quantification (n) of migration and invasion assays after CHD9 m6A erasing by dCasRx-ALKBH5 in 22Rv1 cells. n = 3; two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s test. Scale bar, 200 μm.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Integrative analyses of CHD9-regulated target genes and mechanisms.

Unless otherwise indicated, data are presented as mean ± SD from independent experiments (n as specified in each panel). a) Relative mRNA levels of some target genes in 22Rv1 cells transduced with shRNAs, measured by qPCR. n = 3; two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s test. b) GO terms associated with genes downregulated upon CHD9 knockdown by shRNAs in 22Rv1 cells; one-sided hypergeometric test with Benjamini-Hochberg correction. c) Correlation of log2 fold changes between sh1 and sh2 (Pearson’s r; Spearman’s ρ). Top 20 genes were labeled. Black line indicates perfect agreement; blue line the regression fit. d-e) Venn diagrams showing overlap of upregulated (d) and downregulated (e) genes (Jaccard = 0.35; two-sided Fisher’s exact test P < 10−300). f) Correlation of normalized enrichment scores (NES) from GSEA of Hallmark gene sets between sh1 and sh2. Each point represents one pathway; dashed line indicates perfect agreement. g) RT-qPCR analysis of CDKN1A and KLK4 expression in 22Rv1 cells transduced with shG, sh3, or sh4. n = 3; two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s test. h) Volcano plot showing transcriptome changes upon CHD9 m6A writing. Significantly altered genes were defined by fold change ≥ 1.5 and adjusted P < 0.05; two-sided Wald test, Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted. n = three independent experiments. i-j) GO enrichment analyses of significantly upregulated (i) and downregulated (j) genes following CHD9 m6A writing. Bubble size indicates GeneRatio, and color indicates adjusted P values; one-sided hypergeometric test with Benjamini-Hochberg corrections. k) Venn diagram showing the overlap between genes downregulated upon CHD9 knockdown and upregulated upon CHD9 m6A writing; two-sided Fisher’s exact test. l) Flow cytometry analysis of cell cycle distribution in 22Rv1 cells expressing dCasRx-M3 with CHD9-targeting guides or sgNT, using PI and EdU staining. m) ChIP-Seq signal distribution of all CHD9 binding peaks in shGFP and shCHD9 22Rv1 cells. n-o) Overlap of CHD9 high-confident peaks with active chromatin features, including H3K27ac and ATAC-seq peaks.

Extended Data Fig. 8 CHD9 deletion disrupts cell cycle control and DNA damage response pathways.

a) Comparison of cell cycle pathway activity scores between prostate cancer patients with low versus high CHD9 mRNA abundance (median dichotomized; high, n = 183 tumor samples; low, n = 169 tumor samples). Unpaired two-sided Student’s t-test. Box plots show median (center line) and interquartile range (box boundaries), with whiskers extending to 1.5x IQR. b) Bar plot showing the difference in pathway activity scores (high – low) across tumor types. c) Flow cytometry analysis of cell cycle distribution in 22Rv1 cells transduced with control shRNA (shG) or CHD9-targeting shRNAs (sh1, sh2). Cells were stained with propidium iodide (PI) and EdU to assess DNA content and replication activity. d-e) SA-β-gal staining of 22Rv1 cells transduced with shG or CHD9-targeting shRNAs (sh1, sh2) (d). Cells treated with doxorubicin (Doxo) served as a positive control. Scale bar, 100 μm. e) Quantification of senescent cells. Data were mean ± SD; n = 3 independent experiments, with a total of 20 randomly selected fields analyzed across experiments. two-sided unpaired t-tests with Welch’s correction. f) Comparison of DNA damage pathway scores between prostate cancer patients with low versus high CHD9 mRNA abundance (median dichotomized; high, n = 183 tumor samples; low, n = 169 tumor samples). Unpaired two-sided Student’s t-test. Box plots display the median (center line) and interquartile range (box boundaries), with whiskers extending to values within 1.5x IQR. g) Immunofluorescence images showing γ-H2AX foci (green) in 22Rv1 cells transduced with shGFP or CHD9-targeting shRNAs (sh1, sh2). Doxo-treated cells served as a positive control. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Scale bars = 10 μm. h) Quantification of γ-H2AX foci per nucleus corresponding to (g). Horizontal lines indicate mean ± SD (n = 3 independent experiments, with multiple fields or nuclei analyzed per experiment; total n = 8 measurements). Statistical differences were assessed by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test.

Extended Data Fig. 9 CHD9 is a target of YTHDF1 in prostate cancer cell line.

a) Overlap of CHD9 PAR-CLIP data from the HeLa cell line, YTHDF1, blue; YTHDF2, red; YTHDF3, purple. b) RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP)-qPCR assays on YTHDF1 and YTHDF3 in the 22Rv1 cell line to detect the affinity between the CHD9 and the two readers. IgG serves as the negative control. Data were mean ± SD; n = three independent experiments; unpaired two-sided Student’s t-test. c) YTHDF1 and YTHDF3 protein abundance were detected by western blot after RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP)-qPCR. Vinculin is introduced as a background noise indicator. Representative of two independent experiments with similar results. d-e) The CHD9 mRNA abundance (d) and protein abundance (e) were assessed upon overexpression of YTHDF1 in 22Rv1 cells. Data were mean ± SD; n = three independent experiments; unpaired two-sided Student’s t-test. GAPDH was included as a loading control. Molecular mass standards (kDa) were shown on the right. Representative of two independent experiments with similar results. f) The alterations in translation efficiency of the CHD9 protein were analyzed using publicly available ribosome profiling data following the inhibition of YTHDF1 or YTHDF3 in HCT116 and HeLa cells. g) Normalized abundance of m6A at five predicted adenosine sites within the CHD9 m6A peak was measured by SELECT in 22Rv1 cells transfected with control or YTHDF1 siRNAs. Data were mean ± SD; n = three independent experiments; two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s test. h) Western blot showing CHD9 protein abundance in 22Rv1 cells after siRNA-mediated knockdown of YTHDF1, with or without dCasRx-M3-mediated m6A writing at CHD9. Representative of two independent experiments with similar results. i-l) Polysome profiling from control versus YTHDF1-overexpressed i) or -depleted j) 22Rv1 cells, with the intensity of OD260 plotted on the y-axis and sample fractions collected on the x-axis. qRT-PCR analysis showing the distribution of CHD9 mRNA in different polysome gradient fractions from control versus YTHDF1-overexpressed k) and -depleted l) 22Rv1 cells. Data were mean ± SD; n = three independent experiments.

Extended Data Fig. 10 CHD9 interacts with MYBBP1A to regulate its subnuclear localization.

a) Ranked list of CHD9-associated proteins (FDR < 0.05) based on log2 fold change in mass spectrometry analysis; MYBBP1A is highlighted in red. n = two independent experiments. b-d) Western blot confirming CHD9 pulldown efficiency (b), MYBBP1A pulldown efficiency (c), and of CHD9 following MYBBP1A immunoprecipitation (d). GAPDH was included as the negative control. Molecular mass standards (kDa) were shown on the right. Representative of two independent experiments with similar results. e) Proximity Ligation Assay (PLA) signals (red) for CHD9-MYBBP1A interactions in 22Rv1 cells. Controls include single antibody conditions (CHD9 only, MYBBP1A only, AR only), CHD9-AR pair, and no primary antibody. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 10 μm. f) Quantification of PLA signals per nucleus across conditions. Results were shown as mean ± SD; n = three independent experiments. Statistical differences were assessed by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. g-j) Immunofluorescence images and quantification of nucleoplasmic-to-nucleolar intensity ratio of MYBBP1A localization in H358 cells (g–h) and PC-3 cells (i–j) expressing shGFP, CHD9 sh1, or CHD9 sh2. DAPI, CHD9, and MYBBP1A signals were shown as indicated. Scale bar, 10 μm. Quantification was performed from n = 3 independent experiments, with 5 cells analyzed per experiment (total n = 15 cells per condition). Data represent mean ± SD. Statistical differences were assessed by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, X., Wang, Y., Zhu, H. et al. METTL3-based epitranscriptomic editing screening identifies functional m6A sites in cancers. Nat Cancer (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43018-026-01117-2

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

Version of record:

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43018-026-01117-2