Introduction

Rett syndrome (RTT) is a neurodevelopmental disorder caused by mutations in the X-linked gene encoding melty-CpG binding protein 2 (MeCP2) [1, 2]. Patient symptoms are typically recognized in early developmental stages between 6–12 months, including the lack of speech and social engagement, motor abnormalities, and cognitive impairments [3]. MeCP2 is expressed in various types of cells, including neural cells (neurons and astrocytes) and non-neural cells such as endothelial cells and pericytes. Because of the pervasiveness of MeCP2 expression and methyl-CpG binding sites, its mutation influences not only neuronal health and activity but also the function of non-neural tissue in the brain, including vascular networks associated with endothelial cells [4, 5]. RTT patients frequently present with reduced skeletal growth, hypo-perfusion in the area of the midbrain and upper brainstem, and poor circulation [6, 7], implicating a compromised brain microvasculature. In addition, vasculogenesis and angiogenesis toward the neural tube are some of the primitive events in neurodevelopment, occurring before neurogenesis and oligodendrocytogenesis, as well as astrocytogenesis [8]. Vascular formation and differentiation in the brain begins during the early embryonic period and becomes functional shortly after it is formed [9,10,11], whereas astrocytes and myelinated neurons do not appear until soon after birth [12]. Therefore, early vascular alteration accompanied by developmental neurotoxicity at a systems biology level likely has a wide impact on subsequent neurodevelopmental events and disease progression [13,14,15]. Notably, the onset of regression in Rett syndrome(1-3 years) overlaps with a critical window of vascular development and remodeling.

Vascular permeability involves the molecular exchange between vessels, tissues, and organs. In the brain, specifically, the blood-brain barrier (BBB) strictly regulates molecular transport, including nutrients, waste, and toxins in both the influx and efflux directions, to maintain homeostasis of the brain in healthy conditions [16], and its alterations are linked to pathological processes in neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease [17, 18] and Parkinson’s disease [19, 20]. Notably, BBB breakdown is present prior to Aβ plaque accumulation in Alzheimer’s disease patients [21]. Therefore, while BBB breakdown may trigger subsequent decline of neuronal health, resulting in induced neurodegeneration, mitochondrial dysfunction, and aggregation of Aβ, no pathological role of vascular alteration in RTT has yet been shown.

While there is limited direct evidence indicating impaired BBB permeability in both RTT individuals and MeCP2-null mouse models, there is growing indirect evidence for a role. Recent studies show that MeCP2-null mice (Mecp2-/y, Mecp2tm1.1Bird) exhibit alterations in BBB integrity, along with decreased expression of tight junctions, such as OCLN and CLDN5, in the cortex [22]. This may be impacted by increased matrix metallopeptidase 9 (MMP9) expression, inducing degradation of the basal lamina. Vessels from female MeCP2+/− mice show reduced endothelium-dependent relaxation due to reduced nitric oxide availability, secondary to an increase in reactive oxygen species generation [23]. Additionally, RNA sequencing and proteomics approaches reveal morphological alteration of blood vessels in Mecp2tm1.1Jae/+ mice and an increase in the protein levels related to the BBB [24]. Thus, altered brain vascular homeostasis and subsequent BBB breakdown may be induced in MeCP2-deficient mice (MeCP2-null mice). However, the specific role of MeCP2 mutation in human development with respect to vascular permeability and association with neurodevelopmental alteration accompanying neurovascular interaction remains unknown owing to the lack of a disease model representing this complicated pathological process.

Here, we present an engineered 3D microvascular network (MVN) model in microfluidic devices using RTT patient-derived induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells, which carry the MeCP2[R306C] or MeCP2[R168X] mutation, and investigate an endothelial-specific molecular pathway based on the alteration of vascular permeability associated with a vascular-specific microRNA (miR-126). The MeCP2[R306C] mutation in the transcription repression domain is one of the common single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) mutations (comprising 9–10% of cases) that does not influence affinity to the methyl CpG binding domain, but it disrupts the interaction with the NCoR corepressor complex [25]. The MeCP2[R168X] mutation (comprising 11% of cases) is also one of the most common truncating mutations [26]. Although this mutation is located just after the methyl binding domain, it impacts DNA binding capacity by instability, disruption of chromatin interaction, cofactor recruitment, and improper folding, as well as lack of nuclear-localization signal (NLS) [27]. We first modified iPS cells from RTT patients by knocking in the doxycycline (DOX)-inducible ETV2 gene cassette by CRISPR/Cas9, which has become a standard approach for directly and rapidly differentiating endothelial cells [28, 29]. Throughout this study, all experiments were performed on the MeCP2[R306C] line and its isogenic control, whereas critical experiments were also performed on the MeCP2[R168X] line and its isogenic control. iPS-induced endothelial cells (iECs) and fibroblasts were embedded in a fibrin gel in a microfluidic device to form 3D vascular networks, which were subsequently used for permeability tests. Impaired vascular permeability was observed in RTT patient-derived vasculature networks. Subsequent transcriptomic analysis showed that these impartments are associated with the signaling pathway of miR-126, along with decreased tight junction expression mediated by these impairments. Moreover, down-regulating miRNA-126-3p by expressing antisense miRNA-126-3p partially restored the endothelial barrier function and up-regulated tight junctions, inhibiting the Ang2/Tie2 signaling pathway. These results suggest that miR-126-3p is a direct target of MeCP2 and a mediator of vascular impairment caused by MeCP2[R306C] and [R168X] mutations. Furthermore, miR-126-3p may be a promising therapeutic target for restoring vascular impairments more broadly in other disease states as well. Thus, our study supports potential translational applications aimed at rescuing vascular alterations in the early developmental stages of RTT, and potentially in other neurodegenerative and neurodevelopmental disorders.

Results

ETV2 expressing iPS cells derived from RTT patients

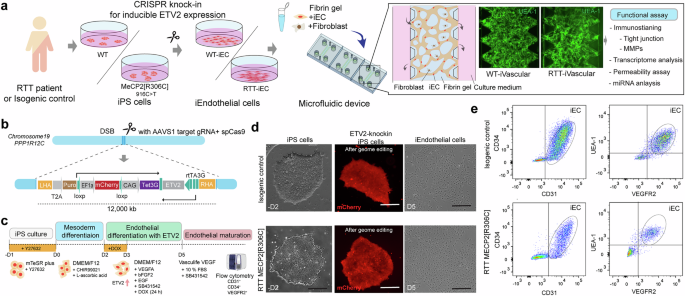

To recapitulate the vascular formation process in early development in RTT and assess vascular permeability, we established a stable iPS cell line from RTT patients, which has DOX-inducible ETV2 expression, providing iECs (Fig. 1a). The all-in-one plasmid that expresses ETV2 under rtTA and Tet3G under CAG bidirectional promoter with mCherry and AAVS1 targeting sgRNA with SpCas9 were constructed from pUCM-AAVS1-TO-hNGN2 plasmid and then delivered to RTT patient-derived iPS cells that carry the MeCP2[R306C] mutation (916 C > T) and isogenic control iPS cells by electroporation (Fig. 1b). SNP mutations in iPS cells were confirmed by Sanger sequencing (Supplemental Fig. 1a). We also established another Dox-inducible ETV2 iPS cell line carrying the MECP2[R168X] mutation (Supplemental Fig. 2a). Genome-edited iPS cells were further separated by cell sorting with mCherry-positive cells and puromycin selection. Although there were fewer than 5% mCherry-positive cells before sorting, we obtained a 100% positive population after cell sorting. To test the response of ETV2 expression in the presence of DOX, we treated iPS cells with DOX for 12, 24, 48, and 72 h and then extracted the protein. Western blotting revealed that ETV2 started to be expressed in genome-edited cells within 12 h and reached full expression within 48 h, although no low ETV2 expression was observed in the absence of DOX in both iPS cell lines because of bidirectional promoters and the 3rd generation Tet-on system (Supplemental Fig. 1b). The pluripotency of iPS cells after genome editing was further characterized by immunostaining with Oct3/4, Nanog, SSEA1, TRA-1-60, and SSEA4, indicating that no unexpressed differentiations occurred (Supplemental Fig. 1c).

a Schematic illustration of engineering RTT’s MVN in the microfluidic device. The RTT patient-derived iPS cells that carry MECP2[R306C] mutations and isogenic controls were modified by knocking in the ETV2-gene cassette using CRISPR/Cas9 to accelerate endothelial differentiation. Then, iECs and fibroblasts were introduced to the microfluidic device to form MVNs. b, c, d ETV2 under Tet3G promoter cassettes were inserted into AAVS1 safe harbor loci, and cells were sorted by FACS based on the mCherry fluorescent marker to obtain a stable iPS cell line. iECs were obtained in 5 days from iPS cells in the presence of DOX. d Single cloned iPS cells (RTT patient-derived cells and controls) with ETV2 gene cassettes (mCherry) and representative images of the endothelial cell morphology 5 days after differentiation. e Endothelial differentiation was confirmed by flow cytometry according to CD31, CD34, VEGFR2, and UEA-1 expression.

Differentiation and characterization of iECs

The ETV2-knock-in iPS cells were then treated with GSK3 inhibitor/Wnt activator (CHIR99021) for 2 days for mesoderm differentiation and then treated with VEGF, EGF, SB43152, and DOX for 1 days to induce differentiation into iECs (Fig. 1c and Supplemental Fig. 2b, c). Flow cytometry showed that iECs expressed CD31, CD34, UEA1, and VEGFR2, which are typical endothelial markers in both RTT patient-derived endothelial cells and the isogenic control cells (Fig. 1e and Supplemental Fig. 2d). iEC tight junctions were characterized by immunostaining with ZO-1 and quantified based on the area fraction of ZO-1. In RTT-iECs, ZO-1 expression decreased and did not localize at the boundary between cells compared with the isogenic control (Fig. 2A). The area fraction of ZO-1 in RTT-iECs was also lower than that in the control (Fig. 2b). RT-PCR results suggested that genes involved in tight junctions, such as ZO-1, OCLDN, CLDN5, were down-regulated (Fig. 2c, d). RTT-iECs also down-regulated the gene expression of transporters, including MCT1, PGP1, LRP1, and GLUT1, compared with wild-type (WT)-iECs and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs; Fig. 2c). We also measured the trans-endothelial electrical resistance (TEER) to assess the barrier function in a 2D monolayer of endothelial cells and found that TEER was lower in RTT-iECs than in WT-iECs and HUVECs after 21 days of culture (Fig. 2e). RNAseq revealed down-regulated (1162, p < 0.05) and up-regulated genes (1163, p < 0.05) and a global effect of the MeCP2[R306C] mutation in RTT-iECs (Fig. 2f, g). We also found that ZO-1 expression was down-regulated in RTT-iECs (Fig. 2f). According to GO enrichment analysis, molecular pathways related to the “regulation of vascular development” and “protein localization to cell-cell junctions” were down-regulated in RTT-iECs (Fig. 2h). In addition, we also observed downregulation of ZO-1 expression in MECP2[R168X] mutant iECs compared to the isogenic control (Supplemental Fig. 2e). It should be noted that we also observed upregulation of genes involved in cell–substrate adhesion, which may reflect enhanced integrin–ECM signaling that dynamically interacts with cell–cell adhesion pathways [30, 31] (Fig. 2h). Since both systems share cytoskeletal and signaling networks including integrin–FAK–Rho GTPase pathways [32, 33], substrate adhesion could negatively regulate endothelial junction stability and barrier function along with downregulation of cadherin junctions, suggesting a coordinated regulation of endothelial architecture through mechanotransduction.

a Immunostaining of ZO-1 (green) and F-actin (red) to quantify the tight junction properties. b Quantification of the ZO-1 area fraction rate. Mut-iECs displayed lower area fractions than WT-iECs. c Gene expression related to characterizing endothelial cells in HUVEC and WT-iEC and RTT-iEC. d Mut-iECs exhibited lower gene expression related to tight junctions (CLDN5, OCLN, and ZO-1), as measured by PCR (n = 3). e Measurement of TEER, indicating endothelial barrier functions. f, g Differential gene expression determined by RNAseq (n = 2). h GO enrichment analysis. Student’s t-test, **, p < 0.01, * p < 0.05.

To further quantify the endothelial characterization, imaging-enhanced flow cytometry was performed with RTT-iEC with MeCP2[R306C] mutations (Fig. 3a), enabling validation of the morphological characteristics on top of the cell surface after marker staining (ZO-1). The flowed cells were gated to identify single cells in the acquired images, considering the combined FSC and SSC values, and then the cell cycle was evaluated by DAPI staining. RTT-iECs showed clear S phase arrest from the G0/G1 phase, whereas WT-iECs exhibited a typical cell cycle (Fig. 3b, c). Based on calculation of perimeter, pseudo-diameter, entropy, and circularity of the cells from the images, they were mapped onto a UMAP plot (Fig. 3d, e). We classified 6 identical clusters based on these 4 parameters and overlaid other information (cell cycle tag, mutation of MeCP2, and ZO-1 expression from immune flow chemistry, Fig. 3f). We classified the ZO-1 highly expressed clusters (Clusters 3 and 4) and typical endothelial cell clusters (Clusters 2 and 5), including other cell types or dead cells (Clusters 1 and 6, Fig. 3g). The population of WT cells was higher than that of RTT-iECs in Cluster 3, and the population of WT cells was lower than that of RTT-iECs in Cluster 5 (Fig. 3h, i, j). These results showed that RTT-iECs could be differentiated into endothelial cells that have lower ZO-1 expression than WT-iECs and suggested that MeCP2 R306C mutation itself negatively impacted the integrity of tight junctions in differentiated endothelial cells.

a Schematic illustration of imaging-enhanced flow cytometry. b, c Single-cell gating and CD31-positive cells were determined. d Cell cycle analysis with DNA staining. e RTT-iECs had higher populations of the G0/G1 cycle. f Representative image of WT-iECs and Mut-iECs according to different cell cycles. Perimeter, pseudo-diameter, entropy, and circularity were quantified from the images. g UMAP plot shows the diverse population of endothelial cells. h, i Feature plot of ZO-1 indicates a unique cluster (Cluster 3, which expresses higher ZO-1). We determined the endothelial cell clusters (Clusters 2, 4, 5) and highly expressed ZO-1 cluster (Cluster 3). Clusters were determined based on four morphological features (perimeter, pseudo-diameter, entropy, and circularity). j Quantification of the number of cells in each cluster. The number of cells in Cluster 3 is higher in WT-iECs than in RTT-iECs.

Conditioned medium was collected from iECs and added to the iPS-derived neurons (NGN2-driven). We then performed calcium imaging to analyze the differential impact of secreted protein from endothelial cells to neuron cells (Supplemental Fig. 3a, b). Treatment with conditioned medium from WT-iECs and RTT-iECs did not affect the neurite length or number of cells (Supplemental Fig. 2c); however, conditioned medium from RTT-iECs negatively impacted the neuronal activity in healthy neurons (Supplemental Fig. 1d, e, f). This result suggested the occurrence of altered neurovascular coupling mediated by a paracrine signal from endothelial cells to neurons.

Impairment of vascular permeability in RTT patient-derived 3D MVNs

Characterization of the RTT-iEC 2D monolayer by gene expression analysis demonstrated altered expression of tight junction proteins. Although the 2D TEER measurement is commonly used to estimate the paracellular barrier function of endothelial cells, it provides no information on transport of specific molecules other than ions. To measure vascular permeability, we engineered 3D MVNs in microfluidic devices using WT-iECs and RTT-iECs. The cells were suspended in fibrin gel solution with normal human lung fibroblasts as supporting cells and introduced into the device’s center channel. After gelation for 15 min, culture medium was introduced into the side channel and cultured for 5 days, resulting in the formation of a MVN in the microfluidic device (Fig. 4a). Both WT-iECs and RTT-iECs could form 3D perfusable MVNs in 5 days (i.e., WT-iVascular and RTT-iVascular). Notably, RTT-iVascular consisted of vessels with slightly smaller diameters than WT-iVascular (Fig. 4b). Texas-red conjugated 70 kDa dextran perfusion helped to further visualize the perfusability and circularity of the microvasculature, although no significant difference was observed in the roundness of the vasculatures (Fig. 4c). To measure permeability of the endothelial barrier in the 3D MVNs, imaging was performed 10 min after 70 kDa dextran injection (Fig. 4d). RTT-iVascular showed higher permeability than WT-iVascular (Fig. 4e). Immunostaining with ZO-1 demonstrated that WT-iVascular was denser, with clearer cell-cell boundaries and higher ZO-1 intensity than RTT-iVascular (Fig. 4f). In addition, we stained MVNs with collagen IV to characterize the basement membrane and observed no significant differences (Fig. 4g). We also collected the culture medium from the device and quantified the MMP and TIMP levels because these secreted proteins have important roles in developmental processes, and MeCP2-null mutations in mice have been shown to influence the secretion level of MMP9 [22]. Unlike previous studies using mouse models, no significant difference in MMP9 level was observed between WT-iVascular and RTT-iVascular; however, we observed clear differences between MMP8, TIMP1, and TIMP4 levels (Fig. 4h). MMP8 is another crucial collagen-cleaving enzyme, and TIMP1 is a natural inhibitor of MMPs [34]. Impaired MMP8 and TIMP1 activity in RTT-iVascular could be one of the triggers for the decreased barrier function measured by permeability assay under 3D conditions. Next, we engineered 3D BBBs in microfluidic devices using WT-iECs and RTT-iECs, namely astrocytes and pericytes (Supplemental Fig. 3a). All three types of cells were suspended in fibrin gel solution and introduced into the center channel of the device, resulting in BBB formation (Supplemental Fig. 4b). Similar to the vasculature, BBBs that express mutant MeCP2 in endothelial cells exhibited higher permeability (Supplemental Fig. 4c).

a WT-iECs and RTT-iECs were embedded in fibrin gel with fibroblasts and introduced into microfluidic devices to form MVNs. In both WT- and RTT-iEC case, MVNs were formed within 5 days. b RTT-iVascular exhibited slightly but significantly smaller vasculature diameters. c There is no significant difference in the vasculature roundness. d Permeability of the endothelial layer was quantified by the perfusion of 70 kDa Texas-red conjugated dextran solution. e RTT-iVascular exhibited higher permeability, indicating lower barrier function of the endothelial layer. f Immunostaining of ZO-1 in 3D MVNs. The ZO-1 intensity was lower in RTT-iVascular than in WT-iVascular. g Both WT-iVascular and RTT-iVascular produced collagen IV, with no significant difference. h MMP and TIMP1 levels were quantified from conditioned medium in 3D MVNs. RTT-iVascular secreted higher MMP8 and TIMP4 and lower TIMP1, but there was no significant difference in MMP1 or MMP9. Student’s t-test, **, p < 0.01, * p < 0.05.

Pathological mechanism associated with endothelial-specific miR-126 dysregulation

microRNAs are small noncoding RNAs that function as post-transcriptional regulators of gene expression. They play a vital role in numerous biological processes, including proliferation, differentiation, and development at the posttranslational level [35]. The involvement of MeCP2 in the regulation of miRNA expression was first reported in 2010 [36, 37]. Furthermore, miR-199a has been shown to control the function of neurons mediated by mTOR signaling [38]. However, whether this MeCP2/miRNA pathway is implicated in other aspects of vascular integrity in RTT remains unexplored. To elucidate how MeCP2 mutation results in decreased tight junction protein, we focused on microRNA expression, especially endothelial cell-specific microRNA, miR-126-3p, in 2D cultured endothelial cells (Supplemental Fig. 5a). Total microRNA was isolated from WT-iECs and RTT-iECs in 2D culture, and then the microRNA expression was quantified by RT-PCR using the appropriate internal control (Supplemental Fig. 5b, c). As a result, miR-126-3p expression was significantly higher in RTT-iECs than in WT-iECs (Fig. 5a). miR-126-3p is only expressed in endothelial cells and acts upon various transcripts to control angiogenesis [39]. Several target genes were displayed using the MirTarget prediction algorithm [40] (Fig. 5b). VEGF-A, SPRED1, and PIK3R2 play important roles in controlling vascular integrity. RT-PCR results showed that EGFL7, IGFBP2, BEGFA, ADAM9, SPRED1, and PIK3R2 were down-regulated, but not HIF1A or NFKBIA, in RTT-iECs, compared with WT-iECs (Fig. 5c).

a miR-126-3p was highly expressed in RTT-iECs compared with isogenic control endothelial cells. b miRDB predicts the target genes of miR126-3p. c Down-regulation of gene expression, targeted by miR126-3p. d miRNA-integrated analysis performed using RNAseq data and the predicted gene expression measured by PCR-based miRNA expression analysis, along with the miRDB prediction. e Down-regulation and up-regulation of the miRNAs from RTT-iECs over WT-iECs. f Seven up-regulated microRNA were determined by miRNA expression analysis, and e the related endothelial cells. g GO enrichment analysis (biological process) from the predicted down-regulated gene set determined by miRDB and miRNA expression analysis e. Significant down-regulated pathways (regulation of vascular development) were determined. h Cnetplot suggested that the genes involved in these signaling pathways include END1 and TEK1. i miRNA-RNA integrated analysis revealed 21 overlapping down-regulated genes, including EDN1 and TEK1, which are also consistent with the RNAseq analysis j, which potentially involved miR126-3p-mediated vascular alteration.

To further clarify the effect of miRNA expression in mutant endothelial cells, we performed miRNA-mRNA multi-modal analysis to estimate the influence of miRNA expression and target mRNA gene expression (Fig. 5d). The differential miRNA expression in RTT-iECs was shown in Fig. 5e. We further considered the reasonable differential miRNA (p < 0.01) and fold change (more than 2.5 times). miRNAs, including hsa-miR-126-3p, hsa-miR-140-3p, hsa-miR-15b, hsa-miR199a-5p, hsa-miR-223-5p, hsa-miR-483-3p, and has-miR-590-5p, were up-regulated, but hsa-miR-29a-3p, hsa-miR-29c-3p, hsa-miR-363-3p, and hsa-miR-652-3p were down-regulated (Fig. 5e). Alluvial plots helped reveal the target genes of differential miRNA according to the miRDB target gene list, and we performed GO enrichment analysis with respect to the biological processes based on up-regulated and down-regulated genes (Fig. 5f and Supplemental Fig. 5d). We discovered one overlapped up-regulated molecular pathway (cell cycle G2M phase translation, Supplemental Fig. 5e, f) and three overlapped down-regulated molecular pathways (“(positive) regulation of vascular development” and regulation of miRNA metabolism processes) from the miRNA-mRNA profiling (Fig. 5g). According to Cnetplot, in addition to the overlap genes found by miRNA-RNA profiling (Fig. 5h, i), the down-regulation of Angiopoietin-1 receptor (TEK) and endothelin-1 (EDN1) in RTT-iECs was observed in both the down-regulated gene expression measured by RNAseq and the gene expression predicted from miRNA expression and miRDB (Fig. 5j). The Angiopoetin-1/Tie2(TEK) signaling pathway plays an important role in vascular stabilization via the phosphorylation of PI3K/AKT and in the forkhead box protein (FOXO1), RhoA, VE-PTP signaling pathways [41, 42]. Endothelin-1 is a vasoconstrictor peptide that regulates vascular dilation in smooth muscle cells and cell migration in endothelial cells. These mechanobiological sensors are involved in both EDN-1 and Ang1/2/Tie2 signaling and regulate vascular homeostasis, and their dysregulation leads to destabilization against external stimuli such as shear stress. In addition, upregulation of miR126-3P expression in iEC with MECP2[R168X] mutation along with upregulation of FOXO1 and ANGPT2 was observed (Supplemental Fig. 2e, f). Therefore, these two genes may play important roles in barrier dysfunction in mutant RTT-iVascular mediated by altered miRNA expression. This miR126 mediated vascular impairment caused by the MECP2 mutation may represent a broader phenotype associated with MeCP2 deficiency rather than being limited to a specific mutation.

Finally, to confirm miR-126-3p-mediated dysregulation of vascular permeability, the antisense of miR126-3p was transfected to RTT-iECs by lentivirus, and the vasculature was formed in a microfluidic device, followed by permeability measurements (Fig. 6a). Immunostaining of ZO-1 showed that miRNA-126-3p knockdown led to an increase in ZO-1 expression in the 3D MVNs (Fig. 6b). In addition, conditional knockdown of miRNA-126-3p could partially restore the endothelial barrier function, as characterized by permeability measurement with 70 kDa dextrans (Fig. 6c, d). To determine how this restoration occurred, we performed RT-PCR focusing on the genes involved in the TEK and EDN-1 signaling pathways (Fig. 6e). As shown earlier, we confirmed the down-regulation of TEK and EDN-1 in RTT-iECs, along with the up-regulation of FOXO1 and ANGPT2 and the regulation of EGFL7 and CLDN5. Knockdown of miR-126-3p restored the expression level of TEK, EDN-1, FOXO1, ANGPT2, and CLDN5 (Fig. 6e). The activation of FOXO1 and PI3K works as a positive feedback regulator of the Ang-2/Tie2 signaling pathway [41, 42], which leads to junction instability and less tolerance against shear stress, along with RhoA and CLDN5 down-regulation (Fig. 6f, g). EDN-1 is not a direct regulator that modulates the tight junction property; however, endothelin-1, a vasoconstrictor peptide, plays a critical role in adjusting blood pressure [6, 7], and its restoration should be important for homeostasis of the vascular integrity. Therefore, we conclude that the MeCP2[R306C] mutation impacts miR-126-mediated dysfunction and vascular integrity, along with TEK and EDN-1 down-regulation, in the early development process in RTT, and its restoration may be a promising therapeutic strategy for the disorder.

a Lentivirus vector used to deliver antisense-miR126-3p and EGFP to down-regulate miR126 expression. b After endothelial differentiation, the cells were transfected with lentivirus, and EGFP-positive cells were sorted (n = 5). c, d Representative images and permeability analysis of RTT-iVascular MVNs with or without expressing miR126-3p knockdown constructs (green) perfused with 70 kDa Dextran (red) (n = 30). e RT-PCR revealed that EGFL7, TEK, EDN-1, and CLDN5 were down-regulated in RTT-iECs, and knockdown of miR126-3p recovered TEK and EDN-1 expression, along with the rescue of FOXO1 and CLDN5 (n = 3). f Gene function prediction involved in Ang/Tie2 signaling and tight junction stabilization based on the GeneMANIA algorithm. g Schematic illustration of the altered gene pathways in RTT-iECs. Student’s t-test, *, p < 0.05, **, p < 0.01, ****, p < 0.0001.

Discussion

This study describes miRNA-126-mediated vascular alterations in RTT MVNs. We established ETV2-expressing iPS cells that express mutations, including MeCP2[R306C] (Figs. 1–6) or MeCP2[R168X] (Supplemental Fig. 2), and native MeCP2, by employing CRISPR/Cas9, which allowed us to rapidly obtain endothelial cells (Fig. 1) and then create MVNs in a microfluidic device (Fig. 3). Location controlled knock-in of a gene cassette containing Tet-ETV2 into the AAVS1 locus was achieved, enabling stable and reproducible endothelial differentiation over lentivirus-based ETV2 overexpression [43] and transfection with mRNA [44], thus minimizing line-dependent (donor-dependent) variations. Although we previously reported on the fabrication of MVNs [45,46,47,48], this is the first in vitro model that mimics early developmental vascular alteration in RTT, specifically focusing on endothelial barrier function regulating the permeability of molecules, using patient-derived iPS cells. In both the 2D and 3D characterization of iECs, tight junction gene expression (ZO-1) was down-regulated in the endothelial cells and vasculature derived from RTT patients (Figs. 2, 3, and 4). One of the most important findings of this study is that RTT-iVascular could be obtained from RTT patient-derived iPS cells, and that this vasculature displayed impaired endothelial barrier function (Fig. 4e). This discovery is consistent with previous literature based on MeCP2-null mice (Mecp2-/y, Mecp2tm1.1Bird) [22, 23]. Although the MeCP2-null mouse model causes an increase in MMP9, which should be involved in BBB disruption, we did not observe MMP1 or MMP9 dysregulation (Fig. 4h), which are critical proteases for vascular turnover with collagen. This may be explained by the structural differences in the non-catalyst domains of MMP2 and MMP9, which affect substrate binding and cause differences in interactions between humans and mice [49,50,51], suggesting the importance of a human in vitro RTT model over a mouse model.

Transcriptome analysis revealed that MeCP2[R306C] mutation in endothelial cells down-regulated the “regulation of vascular development” and “protein localization to cell-cell junctions” in RTT-iECs (Fig. 2f, h). This result indicates that MeCP2 plays an important role in vascular development and the homeostasis of vascular integrity, and MeCP2[R306C] mutations negatively impact it. This downregulation also can be seen in iECs with MECP2[R168X] mutation. To clarify how MeCP2[R306C] mutations influence endothelial barrier function and tight junction potential, we focused on endothelial-specific miRNA-126-3p. This miRNA is critical for endothelial differentiation and development [52, 53] and is involved in vascular disease [54]. We discovered that miRNA-126-3p is highly expressed in RTT-iECs (MeCP2[R306C] or iEC with the MeCP2[R168X] mutation) compared with their isogenic control, and down-regulated target gene expression of miRNA-126-3p in RTT-iEC, including EGFL7, IGFBP2, BEGFA, ADAM9, SPRED1, and PIK3R2 (Fig. 5f, Supplemental Fig. 2e, f). Integrated analysis of miRNA profiling and RNAseq further supported the miRNA-126-3p mediated dysregulation of vascular integrity in RTT-iECs (Fig. 5f, g), along with the down-regulation of TEK and EDN-1, which are important genes for junction stabilization and cell survival, as well as the regulation of vasoconstriction (Figs. 5h, i, j and 6f, g). Down-regulation of TEK caused up-regulation of the FOXO1 and PI3K signaling pathways, thus activating the Ang2/Tie2 positive feedback loop and leading to vascular instability (Fig. 6e). EDN-1, producing endothelin, is an important driver of vasoconstriction and blood pressure regulation. Down-regulation of EDN-1 in RTT-iECs can explain the poor circulation of blood in RTT patients, which has been shown in previous studies [6, 7], along with eNOS down-regulation [23]. Moreover, the knockdown of miR-126-3p in RTT-iECs could rescue the phenotype of MVNs, along with the restoration of TEK and EDN-1 gene expression (Fig. 6e). Taken together, these results show that miR-126-3p is one of the direct targets of MeCP2 and a mediator of vascular impairment caused by MeCP2[R306C] mutations, making it a therapeutic target for restoring vascular function.

In the transcription of microRNA, MeCP2 directly interacts with RNA polymerase II to modulate their transcription, and the mutation of MeCP2 disturbs downstream processing [55, 56]. Additionally, the interaction between Drosha and DGCR8, along with MeCP2, plays an important role in the processing of miR-199a, during the synthesis of precursor miRNA (pri-miRNA), and a lack of MeCP2 (MeCP2 null) down-regulates miR-199 level in neurons, resulting in altered axon development, synapse formation [38, 57], and stem cell fate specification [58]. On the other hands in MeCP2 SNP mutations, miR199 and 214 are upregulated in MeCP2 mutant organoids (R106W and V247X) and cause increased neurogenesis but decreased neuronal migration [59]. Unlike neurons, the role of micro RNAs such as miR-126 [52] and miR-17/92 [60] in vascular development is known in that their overexpression impair BBB function [61] and decreases VCAM-1 expression [62]. However, their specific contribution in the context of Rett syndrome endothelial dysfunction due to MeCP2 mutations remains unclear. Our study is the first to describe the microRNA-mediated role of MeCP2 in vascular development, which may lead to subsequent impairment of neuronal activity, considering that BBB breakdown is one of the fundamental biological events in Alzheimer’s disease [39], Huntington’s disease [63], and other neurodegenerative and neurodevelopmental disorders [64, 65]. Therefore, altered vascular impairment by MeCP2 mutation, which we demonstrate here, may presumably influence neurogenesis and lead to alterations in the brain microenvironment. Another study showed that neuronal activity regulates BBB efflux transport and cross-talk with each other [66], but there is little clear evidence of a link between vascular impairment and neuronal deficits in human RTT patients, although it has been shown in a mouse model [22]. This in vitro microvascular model obtained from patient-derived cells and its co-culture capability with neurons [46] may provide new tools for investigating neurovascular interactions in the context of early developmental changes in RTT, potentially offering new translational opportunities. In this study, we did not provide direct evidence of how MeCP2 regulates miR-126 or how mutant MeCP2 reduces its expression. Addressing these questions would require epigenetic analyses such as ChIP-seq, CUT&RUN, or CUT&Tag demonstrating MeCP2 binding at the miR-126 locus, which is beyond the scope of the current study.

In conclusion, we discovered miR-126-3p-mediated vascular alterations by MeCP2[R306C] mutation in RTT, along with down-regulation of TEK and EDN1. The combination of our directed differentiation method in endothelial cells using patient-derived iPS cells with CRISPR/Cas knock-in dox-inducible ETV2 and their use in a microfluidic platform facilitated the production of robust 3D MVNs and allowed us to mimic the vasculogenesis process in RTT and measure important changes in functions such as permeability. Restoration of the miR-126-3p level effectively rescued endothelial barrier function in RTT-iVascular while modulating the Ang/Tie2 signaling pathway and tight junction stabilization. Although miR-126 has long been recognized as a key regulator of vascular integrity and angiogenesis [52, 67, 68], and its dysregulation has been implicated in various vascular pathologies including atherosclerosis [69, 70] and endothelial dysfunction [71], our findings suggest that miR-126–directed inhibitors or gene therapies could be used to modulate vascular repair. Indeed, the miR-126 inhibitor miRisten is currently under clinical trial for leukemia. Expanding its application from leukemia to Rett syndrome may be a promising therapeutic approach to treat Rett syndrome associated with vascular impairment. interventions may not only help restore vascular integrity but also contribute to brain homeostasis and neuronal function. These findings add translational relevance to our study, as modulation of miR-126 activity may represent a potential therapeutic avenue to reestablish endothelial homeostasis in MeCP2-deficient or disease-associated vascular dysfunction in Rett syndrome. Our platform using patient-derived iPS cells and a CRISPR/Cas9-based ETV2 knock-in system with microfluidic devices may apply to other neurodevelopmental and neurological disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

Materials and methods

iPS cell culture from RTT patient or engineered MECP2 mutant lines

Throughout this study, RTT patient-derived hiPS cells, which carry heterozygous MECP2[R306C] (female, 8Y, missense, 4–7% of RTT patients), and its isogenic control were used, obtained from the Coriell Institute (WIC05i-127-325(MT) and WIC04i-127-33(WT)). The isogenic control cell line was established by site-directed genome editing and CRISPR/Cas9 to fix the mutant allele of MECP2, resulting in isogenic control cells with only the wild-type alleles of MECP2. For a different type of MECP2 mutation, we cloned iPS cells which have the MECP2[R168X] mutation from healthy control human iPS cells (SCTi003-A, STEMCELL Technologies, female, Caucasian, 48Y). Prime editing was used to introduce the MECP2 c.502 C > T (R168X) variant. The prime-editing nuclease expression vector replaced with pCMV-PEmax-P2A-GFP (Addgene, #180020) was employed to provide the prime editor protein. A prime editing guide RNA with pU6-pegRNA-GG-acceptor (Addgene, # #132777) was designed to direct the reverse transcriptase-containing editor to the target site and to encode the desired single-nucleotide change [72]. Cells were transiently transfected by electroporation with the prime editor expression plasmid and pegRNA. After recovery, bulk populations were allowed to expand for editing. For isolation of clonal lines, single-cell cloning was performed using single-cell sorting into 96-plates (FACS Melody). Genomic DNA was extracted from bulk populations and from individual clones for genotyping. The targeted locus was amplified by PCR and analyzed by Sanger sequencing to determine the presence and zygosity of the c.502 C > T allele. All hiPS cells were maintained on Matrigel-coated 6-well plates in mTeSR plus medium (STEMCELL Technologies) with 10 μM Y-23632 (Rock inhibiter, STEMCELL Technologies) for the first day after passages and subcultured every 5–7 days using ReLeSR reagent (STEMCELL Technologies). The pluripotency of iPS cells was characterized by immunostaining with OCT3/4, Nanog, TRA-1-60, and SSEA4 (Supplementary Fig. 1). The cells were cultured in an incubator under 5% CO2 at 37 °C. pCMV-PEmax and pU6-pegRNA-GG-acceptor were a gift from David Liu (Addgene plasmid # 132777; http://n2t.net/addgene:132777; RRID:Addgene_132777, Addgene plasmid # 174820 ; http://n2t.net/addgene:174820 ; RRID:Addgene_174820)

Genome editing for ETV2 knock-in

To produce a genome-edited iPS cell line that expresses ETV2 for endothelial differentiation and hNGN2 under rtTA promoter, gene constructs were knocked into the safe harbor AAVS1 locus of RTT patient-derived iPS cells and isogenic control iPS cells. For endothelial differentiation, pUCM-AAVS1-TO-hNGN2 (Addgene #105840) was used as the backbone plasmid and digested with PacI (NEB) and NotI (NEB). Then, hNGN2 was replaced with ETV2 by Gibson cloning using donor constructs with a 40 bp overlap sequence (gBlock, IDT) to obtain pUCM-AAVS1-TO-ETV2. iPS cells were cultured in 6-well plates coated with Matrigel in mTeSR plus medium and detached using TrypLE Express for 5 min. A total of 2×106 human iPS cells were co-transfected with 8 µg of PX458-AAVS1 plasmid, which expresses SpCas9, and 6 µg of pUCM-AAVS1-TO-ETV2 or pUCM-AAVS1-TO-NGN2 in 100 µl of Opti-MEM. Electroporation was performed using a BTX ECM830 electroporator (Poring plus: voltage,150 V; pulse length, 5 ms; pulse, 100 ms; number of pulses, 2. Transfer pulse: voltage, 20 V; pulse length, 100 ms; pulse, 100 ms; number of pulses, 5). After electroporation, iPS cells were seeded onto Matrigel-coated plates in mTeSR plus with CloneR2, and 24 h post-electroporation, transfected iPS cells were subjected to the puromycin selection at 0.25 μg/ml with 10 μM of Y-27632. Then, the culture medium was replaced with mTeSR plus and allowed to recover for one week. Once the cells reached 80% confluence, they were dissociated by treatment with TrypLE Express (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 5 min. Next, the cell suspension was filtered using 70 µm cell strainers (BD Falcon) in mTeSR plus medium. mCherry-positive cells were sorted using a cell sorter (BD Melody) and re-plated as a single clone to a Matrigel-coated plate in mTeSR plus with CloneR2 to obtain a single colony. Expanded single colonies were then collected for genotyping. PX458-AAVS1 was a gift from Adam Karpf (Addgene plasmid #113194; http://n2t.net/addgene:113194; RRID:Addgene_113194) and pUCM-AAVS1-TO-hNGN2 was a gift from Michael Ward (Addgene plasmid # 105840; http://n2t.net/addgene:105840; RRID:Addgene_105840).

Genotyping

DNA was collected from genome-edited iPS cells using a QIAamp DNA Kit (Qiagen). Gene fragments around the AAVS1 locus were amplified by PCR to confirm that the donor DNA sequence was correctly inserted into the AAVS1 locus (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Differentiation to endothelial cells

Genome-edited iPS cells (ETV2-iPS cells), carrying either MECP2[R306C] or MECP2[R168X] mutations were plated onto Matrigel-coated 6-well plates and cultured until the cells reached 70–80% confluence. At day 0, the cells were treated with 1 ml of Accutase and incubated for 4 min, then 1 mL of mTeSR plus was added for neuralization. Collected cells were further dissociated by pipetting up and down 10 times with a 1 ml pipette tip to obtain single cells. Then, the cells were re-plated to Matrigel-coated 6-well plates at 250,000–350,000 cells/well in mTeSR plus medium and 10 μM Y-23632. The next day, the culture medium was replaced with mesoderm differentiation medium (DMEM/F12 supplemented with 1% GlutaMAX, 60 µg/ml of L-ascorbic acid, 6 µM of CHIR99021(GSK3 Inhibitor/WNT Activator, STEMCELL Technologies)) and cultured for 2 days with a daily medium change. Then, the culture medium was replaced with endothelial differentiation medium (DMEM/F12 supplemented with 1% GlutaMAX, 60 µg/ml of L-ascorbic acid, 50 ng/ml of VEGF-A, 50 ng/mL of bFGF2, 10 ng/mL of EGF, and 10 µM of SB431542 (Activin/BMP/TGF-beta inhibitor, STEMCELL Technologies)) and 3 µg/ml of DOX. The next day, the medium was changed to the same endothelial differentiation medium but without DOX. At day 5, differentiated iECs were seeded to a T150 culture flask for expansion using a Vasculife VEGF Endothelial Medium Complete Kit (Lifeline cell technology, LL-0003) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 10 µM of SB431542, followed by flow cytometry.

Differentiation to neurons

Genome-edited iPS cells (NGN2-iPS cells) were plated onto Matrigel-coated 6-well plates and cultured until the cells reached 70–80% confluence. At day 0, the cells were treated with 1 ml of TrypLE Express and incubated for 5 min, and then 5 ml of mTeSR plus was added for neuralization. Collected cells were further dissociated by pipetting up and down 10 times with a 1 ml pipette tip to obtain single cells. Then, the cells were re-plated to Matrigel-coated 6-well plates at 200,000 cells/well in mTeSR plus medium and 10 μM Y-23632. Two days later, the culture medium was replaced with neuronal initiation and differentiation medium (knockout DMEM/F12 supplemented with 15% KnockOut Serum replacement, 1% GlutaMAX, 1% NEAA, 10 µM of SB431542, 100 nM of LDN-193189 (TGF-beta/Smad inhibitor, STEMCELL Technologies)), as well as 100 ng/ml of DOX, and cultured for 7 days with a daily medium change. Then, the cells were treated with 1 ml of Accutase and incubated for 10 min. Dissociated cells were spun down and resuspended in neuronal maturation medium (Neurobasal plus medium supplemented with 2% B27-plus, 1% N2, and 100 ng/ml of DOX (only for the first 3 days)) and seeded on Matrigel-coated 6-well plates and cultured for 10 days. Differentiated neurons were characterized by RT-PCR and used for Ca2+ imaging.

Imaging-enhanced flow cytometry

To characterize the heterogeneity and tight junction expression of differentiated iECs (RTT-iECs and WT-iECs), imaging-enhanced flow cytometry (Attune CytPix, Thermo Fisher Scientific) was performed. iECs were dissociated with TrypLE Express and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and 0.2% Triton X-100, and then the cells were filtered using 70 μm cell strainers (BD Falcon, 38030) in 1% BSA-phosphate buffer saline (PBS). Then, fixed cells were stained with Alexa Fluor 488 conjugated ZO-1 antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific, ZO1-1A12, 1:100) and Hoechst 33342 for DNA staining and cell cycle analysis. In CytPix, the cell population was gated based on the FSC, SSC, and acquired image to obtain single cells. From the acquired images, the cell size, perimeter, pseudo-diameter, entropy, and circularity were computed using CytPix, and the integrated data (images, FSC, SSC, ZO-1 fluorescent value) were further analyzed using MATLAB (Mathworks).

Engineering of the 3D micovascular networks

Differentiated iECs at 8 ×106 cells/ml and human lung fibroblasts (Lonza, CC-2512) at 1×106 cells/ml as supporting cells were suspended in VascuLife containing thrombin (4 U/ml, Sigma). Cell suspension was further mixed with fibrinogen (final concentration of 3 mg/ml, Sigma) on ice. The mixture was then introduced to the microfluidic device (idenTx 3, AIM Biotech) through the center channel. After introducing the gel mixture with cells, the device was incubated for 15 min to complete the polymerization. Subsequently, VascuLife media supplemented with 10% FBS and 10 µM of SB431542 were introduced into the side medium channel in the devices. The cells were further cultured to allow microvasculature formation, and the permeability assay was performed on day 7 after cell seeding.

Permeability measurements in the 3D vasculature

Vascular permeability was measured for various perfusable MVNs engineered in this study, following published protocols [45, 47]. Briefly, 70 kDa Texas-red dextran (Invitrogen) was perfused into the MVNs by generating a slight pressure gradient across the gel of the device. Specifically, the culture medium in one media channel was first aspirated, followed by the 10 µl injection of 10 µg/ml Texas-red dextran solution. The process was then repeated for the other media channels before imaging under a confocal microscope. Confocal images were captured with a 5 µm step size at 0 and 10 min, from which the permeability was calculated. The detailed permeability measurement protocol and ImageJ Marco for permeability analysis can be found in a previous report [48]. Several regions of interest (ROIs) were captured via time-lapse volumetric imaging for each device.

Quantification of mRNA and microRNA by real-time qRT-PCR and RNAseq

Total RNA was isolated from the cells from 2D culture using RNAeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) following manufacture protocol. Total RNA was converted to cDNA using a Superscript VILO cDNA Syntheses Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). qRT-PCR was performed using Quantstudio 3 (Applied Biosystems) and Takara TB Green Premix Ex Taq II (Takara, SYBR Green). The primer sequences are shown in Table S2. The mRNA level of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as the internal standard in all experiments.

microRNA was isolated using miRNAeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) and further enriched by excluding mRNA and tRNA. microRNA was modified for 3’ poly(A) tailing and 5’ ligation of an aptamer sequence by TaqMan Advanced miRNA cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) to extend mature microRNAs present in the samples on each end prior to reverse transcription, and converted to cDNA. qRT-PCR was performed using TaqMan Advanced miRNA Assay (Assay ID: 477887_mir, for has-miR-126) and TaqMan Advanced miRNA human endogenous control (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with Quantstudio 3 (Applied Biosystems). microRNA levels were normalized by the endogenous control as an internal standard. The RT-PCR experiments were repeated at least 3 times with cDNAs prepared from separate cell cultures along with experimental duplicates. Each reaction was assessed according to the melting curve to exclude abnormal amplification. Differential gene expressions were quantified using the delta-delta Ct method. miR-126-3p binding domain were simulated using miRDB (https://mirdb.org/) [40] and confirmed using TargetScanHuman [73] (https://www.targetscan.org/vert_80/). The GC % and PhyloP score were obtained from the UCSC Genome Browser (https://genome.ucsc.edu/).

RNA-sequencing was performed by the Broad Institute Sequencing Platform. 50 M paired-end configuration and read-data were mapped to human reference genome GRCh37/hg19. Mapped reads were quantified using featureCount. Differential expression was calculated by edgeR package in R, and used to determine significantly altered genes (adjusted p-value < 0.01).

Characterization of neuronal activity by Ca2+ imaging

To characterize the direct impact of paracrine signals from iECs to neurons, we performed Ca2+ imaging using a two-photon microscope. At 3 weeks of culture, iPSC-derived NGN2-induced differentiated neurons were infected with rAAV-hSyn-jRGECO1a-WPRE and then cultured for at least 1 week after the infection. Twenty-four hours before imaging, the culture medium was replaced with BrainPhys imaging optimization medium supplemented with 1% GlutaMAX, 2% B27 plus, 1% NEAA, and 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin. Time-lapse images were acquired using a two-photon microscope (Bruker) with a galvo-resonant scanner and an Insight X3 laser (Spectra-physics, 80 MHz) at 1040 nm for jRGECO1a excitation and a MaiTai laser (Spectra-physics, 80 MHz) at 860 nm for EGFP excitation. Both lasers were aligned with the same light path and scanned at a sampling frequency of 60 Hz, with a resolution of 512 × 512. The emission light was initially separated by a primary dichroic short pass filter mirror (890 nm), and then the green signal and red signal were separated by a dichroic mirror (Semrock, 540/50 nm) and further filtered using 525/25 and 610/45 nm bandpass filters, respectively. Both signals were detected using GaAsP photomultiplier tubes (H7422A-40, Hamamatsu, Japan). The microscope and laser were controlled using Prairie View software (Bruker). Time-lapse images were first analyzed using the Suite2p package (Suite2p, Python 3.12) to identify the signal neurons and segment them by determining the ROIs. For each ROI time series, the baseline fluorescence was defined as the average of the lowest 10% of samples. ∆F/F was computed as (F − Faverage) / Faverage, and photobleaching was also normalized by the slope calculated from (Fend − Fstart) / time. The exported data (delta F) were loaded into MATLAB and further processed according to the analysis. To calculate the spike frequency, delta F was initially deconvoluted to specify single neuron activity, and then spikes were detected using the “findpeaks” function in MATLAB. The spike frequency was calculated over a certain unit of time (min). Correlation matrices were obtained by pairwise correlation among the neurons.

Immunostaining and microarrays

In 2D monolayer cultures, the cells on the glass bottom dish were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 20 min at room temperature. Then, the cells were permeabilized in 0.2% TritonX-100 in PBS for 5 min at room temperature and blocked in 1% BSA in PBS at 4 °C overnight. The primary antibody was then incubated with ZO-1 antibody (ThermoFisher, ZO1-1A12, 1:1000) at 4 °C overnight. After the cells were washed with PBS, the secondary antibody was incubated with Goat anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L) and Alexa Fluor 488 (1:1000) at 4 °C overnight. The cells then were incubated with Rhodamine phalloidin (70 nM) and Hoechst 33342 (1:10000) solution at room temperature for 10 min, followed by washing with PBS 3 times. Fluorescent images were acquired using a confocal microscope (Olympus, FV1200) with 20× UPlanSApo objectives (NA: 0.75).

For 3D cultures in microfluidic devices, PBS was introduced into the medium channel of a microfluidic device and replaced 3 times for washing and removing the medium from MVNs. After removing excess PBS, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 4 h at room temperature on a rocking shaker. Then, the cells were permeabilized in 0.2% TritonX-100 in PBS for 1 h at room temperature and blocked in 1% BSA in PBS at 4 °C overnight. Primary antibody (anti-ZO-1 antibody, ThermoFisher, ZO1-1A12, 1:1000; anti-collagen IV mouse antibody, Abcam, ab19808, 1:500) was introduced into the device and incubated at 4 °C overnight on a rocking shaker. Primary antibodies were carefully removed by washing with PBS for 1 h, which was repeated at least 3 times. Then, secondary antibodies (Goat anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L), Alexa Fluor 555 (1:1000); Goat anti-Mouse IgG (H + L), Alexa Fluor 647 (1:1000)) were incubated at 4 °C overnight on a rocking shaker. The cells then were incubated with Hoechst 33342 (1:10000) solution at room temperature overnight, followed by gentle washing with PBS 3 times. Z-stack images were acquired using a confocal microscope (Olympus, FV1200) with 10× or 20× SApo objectives.

To quantify paracrine signals related to MMPs and TIMPs, the culture media were collected from cultured microfluidic devices. Then, protein expression in the medium was semi-quantitated by G-Series Human MMP Array 1, following the manufacturer’s protocol. ZO-1 boundary expressions were quantified with this established method [74] by using Fiji software (https://imagej.net/software/fiji/). Briefly, fluorescence images of ZO-1 were binarized to define endothelial cell boundaries by manually adjusting the threshold, and a boundary mask was generated. Using this mask, the software measured the gray values from the original image, which were defined as the immunofluorescence (IF) intensity.

Statistical analysis

The reported values are the means of a minimum of three independent experiments, presented as the mean ± SD. For equal variances and normal distributions, a Student’s t-test was performed. To compare groups under multiple conditions, statistical comparisons were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by post hoc pairwise comparisons using the Tukey–Kramer method. Statistical tests were conducted using GraphPad Prism 9 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA), and p-values < 0.05 or 0.01 were considered significant in all cases.

Data availability

Read-level data and fastq file from RNAseq is deposited in the GEO database (GSE314031). Processed data of differential gene expression can be seen in Supplemental Dataset 1. The plasmid (pUCM-AAVS1-TO-hETV2) has been deposited to Addgene (#250998). Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the corresponding author upon request. All other supporting information including MATLAB code used for calculating the pairwise correlation of neuronal activity and the R code used for RNAseq are available from GitHub (https://github.com/TatsuyaOsaki/miR126-RTT-microvascular).

References

-

Lyst MJ, Bird A. Rett syndrome: a complex disorder with simple roots. Nat Rev Genet. 2015;16:261–75.

-

Samaco RC, Neul JL. Complexities of Rett Syndrome and MeCP2. J Neurosci. 2011;31:7951–9.

-

Chahrour M, Zoghbi HY. The story of Rett syndrome: from clinic to neurobiology. Neuron. 2007;56:422–37.

-

Sjöstedt E, Zhong W, Fagerberg L, Karlsson M, Mitsios N, Adori C, et al. An atlas of the protein-coding genes in the human, pig, and mouse brain. Science. 2020;367:eaay5947.

-

Karlsson M, Zhang C, Méar L, Zhong W, Digre A, Katona B, et al. A single–cell type transcriptomics map of human tissues. Sci Adv. 2021;7:eabh2169.

-

Lappalainen R, Liewendahl K, Sainio K, Nikkinen P, Riikonen RS. Brain perfusion SPECT and EEG findings in Rett syndrome. Acta Neurol Scand. 1997;95:44–50.

-

Bianciardi G, Acampa M, Lamberti I, Sartini S, Servi M, Biagi F, et al. Microvascular abnormalities in Rett syndrome. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2013;54:109–13.

-

Saili KS, Zurlinden TJ, Schwab AJ, Silvin A, Baker NC, Hunter ES, et al. Blood-brain barrier development: Systems modeling and predictive toxicology. Birth Defects Res. 2017;109:1680–710.

-

Daneman R, Zhou L, Kebede AA, Barres BA. Pericytes are required for blood–brain barrier integrity during embryogenesis. Nature. 2010;468:562–6.

-

Ek CJ, Dziegielewska KM, Habgood MD, Saunders NR. Barriers in the developing brain and Neurotoxicology. Neurotoxicology. 2012;33:586–604.

-

Saunders NR, Joakim Ek C, Dziegielewska KM. The neonatal blood-brain barrier is functionally effective, and immaturity does not explain differential targeting of AAV9. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:804–5.

-

Obermeier B, Daneman R, Ransohoff RM. Development, maintenance and disruption of the blood-brain barrier. Nat Med. 2013;19:1584–96.

-

Aschner M, Ceccatelli S, Daneshian M, Fritsche E, Hasiwa N, Hartung T, et al. Reference compounds for alternative test methods to indicate developmental neurotoxicity (DNT) potential of chemicals: example lists and criteria for their selection and use. ALTEX. 2017;34:49–74.

-

Bal-Price A, Crofton KM, Sachana M, Shafer TJ, Behl M, Forsby A, et al. Putative adverse outcome pathways relevant to neurotoxicity. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2015;45:83–91.

-

Corada M, Nyqvist D, Orsenigo F, Caprini A, Giampietro C, Taketo MM, et al. The Wnt/beta-catenin pathway modulates vascular remodeling and specification by upregulating Dll4/Notch signaling. Dev Cell. 2010;18:938–49.

-

Weis SM, Cheresh DA. Pathophysiological consequences of VEGF-induced vascular permeability. Nature. 2005;437:497–504.

-

Zlokovic BV. Neurovascular pathways to neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease and other disorders. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12:723–38.

-

Sweeney MD, Sagare AP, Zlokovic BV. Blood–brain barrier breakdown in Alzheimer disease and other neurodegenerative disorders. Nature Reviews Neurology. 2018;14:133–50.

-

Gray MT, Woulfe JM. Striatal blood–brain barrier permeability in Parkinson’S disease. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2015;35:747–50.

-

Shaltiel-Karyo R, Frenkel-Pinter M, Rockenstein E, Patrick C, Levy-Sakin M, Schiller A, et al. A blood-brain barrier (BBB) disrupter is also a potent α-synuclein (α-syn) aggregation inhibitor: a novel dual mechanism of mannitol for the treatment of Parkinson disease (PD) *. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2013;288:17579–88.

-

Lee RL, Funk KE. Imaging blood-brain barrier disruption in neuroinflammation and Alzheimer’s disease. Front Aging Neurosci. 2023;15:1144036.

-

Pepe G, Fioriniello S, Marracino F, Capocci L, Maglione V, D’Esposito M, et al. Blood–brain barrier integrity is perturbed in a Mecp2-null mouse model of rett syndrome. Biomolecules. 2023;13:606.

-

Panighini A, Duranti E, Santini F, Maffei M, Pizzorusso T, Funel N, et al. Vascular dysfunction in a mouse model of rett syndrome and effects of curcumin treatment. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e64863.

-

Pacheco NL, Heaven MR, Holt LM, Crossman DK, Boggio KJ, Shaffer SA, et al. RNA sequencing and proteomics approaches reveal novel deficits in the cortex of Mecp2-deficient mice, a model for Rett syndrome. Mol Autism. 2017;8:56.

-

Lyst MJ, Ekiert R, Ebert DH, Merusi C, Nowak J, Selfridge J, et al. Rett syndrome mutations abolish the interaction of MeCP2 with the NCoR/SMRT co-repressor. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:898–902.

-

Schaevitz LR, Gómez NB, Zhen DP, Berger-Sweeney JE. MeCP2 R168X male and female mutant mice exhibit Rett-like behavioral deficits. Genes Brain Behav. 2013;12:732–40.

-

Nan X, Hou J, Maclean A, Nasir J, Lafuente MJ, Shu X, et al. Interaction between chromatin proteins MECP2 and ATRX is disrupted by mutations that cause inherited mental retardation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:2709–14.

-

Luo AC, Wang J, Wang K, Zhu Y, Gong L, Lee U, et al. A streamlined method to generate endothelial cells from human pluripotent stem cells via transient doxycycline-inducible ETV2 activation. Angiogenesis. 2024;27:779–95.

-

Palikuqi B, Nguyen D-HT, Li G, Schreiner R, Pellegata AF, Liu Y, et al. Adaptable haemodynamic endothelial cells for organogenesis and tumorigenesis. Nature. 2020;585:426–32.

-

Cerutti C, Ridley AJ. Endothelial cell-cell adhesion and signaling. Exp Cell Res. 2017;358:31–38.

-

Komarova YA, Kruse K, Mehta D, Malik AB. Protein interactions at endothelial junctions and signaling mechanisms regulating endothelial permeability. Circ Res. 2017;120:179–206.

-

Marjoram RJ, Lessey EC, Burridge K. Regulation of RhoA activity by adhesion molecules and mechanotransduction. Curr Mol Med. 2014;14:199–208.

-

Aman J, Margadant C. Integrin-dependent cell–matrix adhesion in endothelial health and disease. Circ Res. 2023;132:355–78.

-

Cui N, Hu M, Khalil RA. Biochemical and biological attributes of matrix metalloproteinases. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2017;147:1–73.

-

Issler O, Chen A. Determining the role of microRNAs in psychiatric disorders. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2015;16:201–12.

-

Szulwach KE, Li X, Smrt RD, Li Y, Luo Y, Lin L, et al. Cross talk between microRNA and epigenetic regulation in adult neurogenesis. Journal of Cell Biology. 2010;189:127–41.

-

Urdinguio RG, Fernández AF, Lopez-Nieva P, Rossi S, Huertas D, Kulis M, et al. Disrupted microRNA expression caused by Mecp2 loss in a mouse model of Rett syndrome. Epigenetics. 2010;5:656–63.

-

Tsujimura K, Irie K, Nakashima H, Egashira Y, Fukao Y, Fujiwara M, et al. miR-199a links MeCP2 with mTOR signaling and its dysregulation leads to rett syndrome phenotypes. Cell Reports. 2015;12:1887–901.

-

van Solingen C, Seghers L, Bijkerk R, Duijs JM, Roeten MK, van Oeveren-Rietdijk AM, et al. Antagomir-mediated silencing of endothelial cell specific microRNA-126 impairs ischemia-induced angiogenesis. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13:1577–85.

-

Liu W, Wang X. Prediction of functional microRNA targets by integrative modeling of microRNA binding and target expression data. Genome Biol. 2019;20:18.

-

Saharinen P, Eklund L, Alitalo K. Therapeutic targeting of the angiopoietin–TIE pathway. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2017;16:635–61.

-

Augustin HG, Young Koh G, Thurston G, Alitalo K. Control of vascular morphogenesis and homeostasis through the angiopoietin–Tie system. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:165–77.

-

Zhang H, Yamaguchi T, Kokubu Y, Kawabata K. Transient ETV2 expression promotes the generation of mature endothelial cells from human pluripotent stem cells. Biol Pharm Bull. 2022;45:483–90.

-

Wang K, Lin R-Z, Hong X, Ng AH, Lee CN, Neumeyer J, et al. Robust differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells into endothelial cells via temporal modulation of ETV2 with modified mRNA. Sci Adv. 2020;6:eaba7606.

-

Campisi M, Shin Y, Osaki T, Hajal C, Chiono V, Kamm RD. 3D self-organized microvascular model of the human blood-brain barrier with endothelial cells, pericytes and astrocytes. Biomaterials. 2018;180:117–29.

-

Osaki T, Sivathanu V, Kamm RD. Engineered 3D vascular and neuronal networks in a microfluidic platform. Sci Rep. 2018;8:5168.

-

Offeddu GS, Haase K, Gillrie MR, Li R, Morozova O, Hickman D, et al. An on-chip model of protein paracellular and transcellular permeability in the microcirculation. Biomaterials. 2019;212:115–25.

-

Hajal C, Offeddu GS, Shin Y, Zhang S, Morozova O, Hickman D, et al. Engineered human blood–brain barrier microfluidic model for vascular permeability analyses. Nat Protoc. 2022;17:95–128.

-

Van den Steen PE, Dubois B, Nelissen I, Rudd PM, Dwek RA, Opdenakker G. Biochemistry and molecular biology of gelatinase B or matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9). Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2002;37:375–536.

-

Visse R, Nagase H. Matrix metalloproteinases and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases. Circ Res. 2003;92:827–39.

-

Fanjul-Fernández M, Folgueras AR, Cabrera S, López-Otín C. Matrix metalloproteinases: Evolution, gene regulation and functional analysis in mouse models. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) – Molecular Cell Research. 2010;1803:3–19.

-

Wang S, Aurora AB, Johnson BA, Qi X, McAnally J, Hill JA, et al. The endothelial-specific MicroRNA miR-126 governs vascular integrity and angiogenesis. Dev Cell. 2008;15:261–71.

-

Wang L, Xu W, Zhang S, Gundberg GC, Zheng CR, Wan Z, et al. Sensing and guiding cell-state transitions by using genetically encoded endoribonuclease-mediated microRNA sensors. Nature Biomedical Engineering. 2024;8:1730–43.

-

Qu M-J, Pan J-J, Shi X-J, Zhang Z-J, Tang Y-H, Yang G-Y. MicroRNA-126 is a prospective target for vascular disease. Neuroimmunology and Neuroinflammation. 2018;5:10.

-

Lee Y, Kim M, Han J, Yeom KH, Lee S, Baek SH, et al. MicroRNA genes are transcribed by RNA polymerase II. EMBO J. 2004;23:4051–60.

-

Liu Y, Flamier A, Bell GW, Diao AJ, Whitfield TW, Wang H-C, et al. MECP2 directly interacts with RNA polymerase II to modulate transcription in human neurons. Neuron. 2024;112:1943–.e10.

-

Cheng T-L, Wang Z, Liao Q, Zhu Y, Zhou W-H, Xu W, et al. MeCP2 suppresses nuclear MicroRNA processing and dendritic growth by regulating the DGCR8/Drosha complex. Dev Cell. 2014;28:547–60.

-

Nakashima H, Tsujimura K, Irie K, Imamura T, Trujillo CA, Ishizu M, et al. MeCP2 controls neural stem cell fate specification through miR-199a-mediated inhibition of BMP-Smad signaling. Cell Reports. 2021;35:109124.

-

Mellios N, Feldman DA, Sheridan SD, Ip JPK, Kwok S, Amoah SK, et al. MeCP2-regulated miRNAs control early human neurogenesis through differential effects on ERK and AKT signaling. Mol Psychiatry. 2018;23:1051–65.

-

Chamorro-Jorganes A, Lee MY, Araldi E, Landskroner-Eiger S, Fernández-Fuertes M, Sahraei M, et al. VEGF-induced expression of miR-17–92 cluster in endothelial cells is mediated by ERK/ELK1 activation and regulates angiogenesis. Circ Res. 2016;118:38–47.

-

Pan J, Qu M, Li Y, Wang L, Zhang L, Wang Y, et al. MicroRNA-126-3p/-5p Overexpression attenuates blood-brain barrier disruption in a mouse model of middle cerebral artery occlusion. Stroke. 2020;51:619–27.

-

Harris TA, Yamakuchi M, Ferlito M, Mendell JT, Lowenstein CJ. MicroRNA-126 regulates endothelial expression of vascular cell adhesion molecule 1. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2008;105:1516–21.

-

Di Pardo A, Amico E, Scalabrì F, Pepe G, Castaldo S, Elifani F, et al. Impairment of blood-brain barrier is an early event in R6/2 mouse model of Huntington Disease. Sci Rep. 2017;7:41316.

-

Barisano G, Montagne A, Kisler K, Schneider JA, Wardlaw JM, Zlokovic BV. Blood–brain barrier link to human cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Nature Cardiovascular Research. 2022;1:108–15.

-

Aragón-González A, Shaw PJ, Ferraiuolo L. Blood-brain barrier disruption and its involvement in neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative disorders. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:15271.

-

Pulido RS, Munji RN, Chan TC, Quirk CR, Weiner GA, Weger BD, et al. Neuronal activity regulates blood-brain barrier efflux transport through endothelial circadian genes. Neuron. 2020;108:937–e937.

-

Alique M, Bodega G, Giannarelli C, Carracedo J, Ramírez R. MicroRNA-126 regulates Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1α which inhibited migration, proliferation, and angiogenesis in replicative endothelial senescence. Sci Rep. 2019;9:7381.

-

Bassand, Metzinger L K, Naïm M, Mouhoubi N, Haddad O, Assoun V, et al. miR-126-3p is essential for CXCL12-induced angiogenesis. J Cell Mol Med. 2021;25:6032–45.

-

Chistiakov DA, Orekhov AN, Bobryshev YV. The role of miR-126 in embryonic angiogenesis, adult vascular homeostasis, and vascular repair and its alterations in atherosclerotic disease. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2016;97:47–55.

-

Theofilis P, Oikonomou E, Vogiatzi G, Sagris M, Antonopoulos AS, Siasos G, et al. The Role of MicroRNA-126 in atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases. Curr Med Chem. 2023;30:1902–21.

-

Cheng XW, Wan YF, Zhou Q, Wang Y, Zhu HQ. MicroRNA‑126 inhibits endothelial permeability and apoptosis in apolipoprotein E‑knockout mice fed a high‑fat diet. Mol Med Rep. 2017;16:3061–8.

-

Chen PJ, Hussmann JA, Yan J, Knipping F, Ravisankar P, Chen PF, et al. Enhanced prime editing systems by manipulating cellular determinants of editing outcomes. Cell. 2021;184:5635–e5629.

-

Agarwal V, Bell GW, Nam J-W, Bartel DP. Predicting effective microRNA target sites in mammalian mRNAs. eLife. 2015;4:e05005.

-

Terryn C, Sellami M, Fichel C, Diebold M-D, Gangloff S, Le Naour R, et al. Rapid method of quantification of tight-junction organization using image analysis. Cytometry Part A. 2013;83A:235–41.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH grants R01MH085802 and R01NS130361, MURI grant W911NF2110328, the Picower Institute Innovation Fund, and the Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative through the Simons Center for the Social Brain to M.S. We thank the Koch Institute’s Robert A. Swanson (1969) Biotechnology Center for technical support, specifically with the flow cytometry core. This work also was supported by NIH R01CA190294 to D.A.B. Additional funding was provided by AIRC (Italian Association for Cancer Research) Fellowship for Abroad “Amazon Goes Gold” to M.C., and the Claudia Adams Barr Program for Cancer Research to M.C.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

RDK is a co-founder of AIM Biotech, a company that markets microfluidic technologies and receives research support from Amgen, Abbvie, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Novartis, Daiichi-Sankyo, Roche, Takeda, Eisai, EMD Serono, and Visterra. DAB is a consultant for N of One/Qiagen and Exo Therapeutics, is a founder and shareholder in Xsphera Biosciences, has received honoraria from Merck, H3 Biomedicine/Esai, EMD Serono, Gilead Sciences, Abbvie, and Madalon Consulting, and research grants from BMS, Takeda, Novartis, Gilead, and Lilly and Daiichi Sankyo.

Ethics approval

All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. The use of human iPS cells was reviewed and approved by Picower Institute for learning and memory, Massachusetts Institute of Technology. The human iPS cells were handled in accordance with approved protocols.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Osaki, T., Wan, Z., Haratani, K. et al. miR126-mediated alteration of vascular integrity in Rett syndrome. Mol Psychiatry (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-026-03492-9

-

Received:

-

Revised:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

Version of record:

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-026-03492-9