Introduction: the promise and paradox of OMIECs in bioelectronics

A prevailing vision for next-generation medical diagnostics involves a paradigm shift away from centralized laboratories toward continuous, real-time health monitoring at the point of care (POC) through in vivo and in vitro biosensors1,2. This vision demands sensing technologies that are not only highly sensitive and specific, but also inherently compatible with the complex and dynamic environment of biological systems. Within the field of bioelectronic materials, a unique class of polymers known as OMIECs has emerged as an attractive option. The past few years have witnessed novel biosensing devices enabled by OMIECs that are biocompatible and have superior performance for interfacing with living systems3,4,5,6.

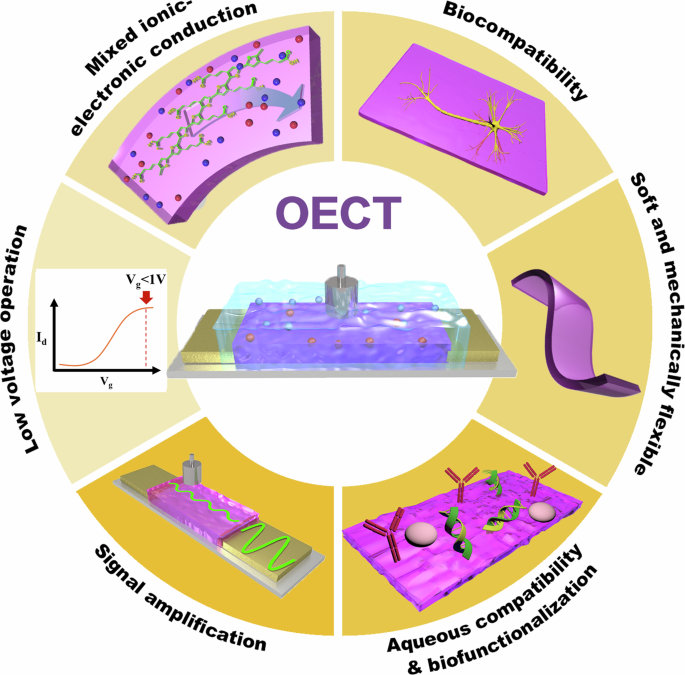

OMIEC materials offer a compelling combination of properties including biocompatibility, mixed ionic-electronic conduction, the ability for signal amplification and ion sensing, aqueous compatibility for biofunctionalization, inherent softness and mechanical flexibility, and low voltage operation, all of which are crucial for advanced biosensing applications (Fig. 1). Specifically, OMIECs possess the defining characteristic of conducting both electronic charge carriers and ions simultaneously7. This dual conductivity allows them to directly interface with the ionic signaling in cells, and translate it into the electronic signals used by modern devices through a unique phenomenon called ionic-electronic coupling8. The modular design of OMIEC materials facilitates the straightforward tuning of both sidechain (length and functional groups) and conducting backbone chemical structures to meet specific application requirements9,10. As soft, polymer-based materials, OMIECs inherently possess a low Young’s Modulus11. This mechanical property is critical for enabling OMIEC-based devices to establish conformal and seamless contact with the soft, dynamic surfaces of biological structures. These foundational properties make OMIECs a versatile material platform for a diverse array of bioelectronic applications4,6.

Specific advantages of OMIECs applied in organic electrochemical transistor (OECT) configurations for biosensing applications, including biocompatibility, mixed ionic-electronic conduction, signal amplification, aqueous compatibility for biofunctionalization, inherent softness and mechanical flexibility, and low voltage operation.

Among the various device architectures built from OMIEC materials, organic electrochemical transistors (OECTs) are widely adopted in biosensing applications. Distinct from conventional organic field-effect transistors (OFETs), which rely on a field effect to modulate charge carriers at a two-dimensional interface between a semiconductor and a dielectric insulator12, OECTs employ a mechanism of volumetric electrochemical doping13. In a typical three-terminal OECT, the channel is composed of an OMIEC, which is in direct contact with an aqueous electrolyte. When a gate voltage (VG) is applied, ions from the electrolyte are driven into the entire bulk volume of the OMIEC channel. This influx of ions electrochemically induces (de)doping of the material, modulating the drain current (ID) flowing between the source and drain electrodes13. This volumetric capacitance effect endows OECTs with exceptionally high transconductance (gm), a key figure of merit that quantifies the ability of the OMIEC to convert a small ionic input signal into a large electronic output signal3.

The inherent signal amplification of OMIEC materials provides OECTs with their most compelling bio-interfacing capabilities. The high gm enables the detection of minute biological signals, such as the binding of a few biomarker molecules or subtle changes in ion concentration without the need for complex and noisy external amplification circuitry8. The replacement of a solid dielectric with an aqueous electrolyte renders the device inherently compatible with biological fluids and enables operation at very low voltages (typically < 1 V), which minimizes power consumption and averts the risk of water electrolysis or damage to delicate biological species14. Furthermore, the use of solution-processable organic materials allows for low-cost, large-scale fabrication via techniques like spray-coating and inkjet printing on flexible substrates, a critical enabler for creating wearable and implantable form factors3.

The very feature that makes the OECTs appealing for biosensing applications, i.e., direct interaction with biological solutions and the volumetric response, is also the source of their great vulnerability. Any nonspecific event that alters the ionic composition of the electrolyte or physically impedes ion transport into the channel volume will contribute to the measurement signal, leading to significant signal drift and inaccuracy. This perspective posits that the primary barriers to translating OECT biosensors from laboratory curiosities to clinically robust tools are the challenges of biofouling, specificity of the detection, and long-term operation stability (Fig. 2). Overcoming these barriers is not merely an engineering task – it is fundamentally related to active material structure-property relationships. The future of OECT biosensors is therefore critically dependent on innovations in OMIEC design that can resolve the inherent challenges posed by the complex bio-abiotic interfaces, and how material and device architectures are co-optimized and functionally integrated.

Schematic representation of the primary barriers to the clinical translation of OMIEC-based biosensors, namely, the interconnected challenges of biofouling, specificity and stability.

Opportunities and challenges for bio-interfacing compatibility in OMIECs

Biosensing applications require physical and chemical compatibility of the sensor materials with the biological systems. In addition, for sensors interfacing with biological fluids, stability of device performance in environments with complex compositions needs to be established8. OMIECs present tunable mechanical properties to match biological systems15 and chemical versatility to enhance the biocompatibility9, however materials innovations are needed to combat the persistent problem of biofouling.

Tunable moduli: achieving mechanical symbiosis

A fundamental obstacle for traditional implantable electronics is the mechanical mismatch between the device and the host tissue. Conventional devices are built from rigid inorganic materials like silicon and platinum, which possess a Young’s Modulus on the order of gigapascals (GPa)16. By contrast, the body’s soft tissues are many orders of magnitude softer15. This disparity can create chronic micro-motions and irritation at the implant site, fueling a foreign body response that culminates in device failure16. This immune-mediated cascade begins when proteins from the body are absorbed onto the implant surface, which in turn triggers the recruitment of immune cells like macrophages and fibroblasts. These cells then deposit collagen, leading to the growth of a thick, insulating fibrous capsule that isolates the implant. For bioelectronic devices that rely on direct electrical contact with tissue, this fibrous encapsulation is particularly damaging, as it significantly increases impedance at the device-tissue interface and decreases signal amplitude, ultimately compromising the device’s long-term function17.

OMIECs, as soft polymer-based materials, inherently solve this problem. They exhibit an intrinsically low Young’s Modulus, with values that can range from hundreds of megapascals down to the kilopascal scale11, allowing OMIEC-based devices to form a seamless, conformal contact with soft and dynamic biological structures. An innovative strategy to further enhance these properties involves creating a hydrogel-semiconductor composite. By incorporating water-insoluble polymer semiconductors into hydrogel networks, materials can be engineered with exceptionally low, tissue-like modulus and high stretchability18. This ultra-soft interface significantly reduces mechanical trauma that drives chronic inflammation, leading to a diminished foreign body response and paving the way for superior long-term integration18,19. Besides, some OMIECs such as the glycolated polythiophene based OMIEC-p(g3T2) even offer the ability to dynamically tune their stiffness in response to electrical signals20, opening the door for adaptive bio-interfaces that can actively modulate their mechanical properties to match the surrounding tissue on demand.

The challenge of biofouling

While OMIECs offer a clear solution to the mechanical challenge, their application in biosensing, particularly in OECTs, is critically hampered by the biochemical phenomenon of biofouling. Biofouling is the rapid and undesired adsorption of biomolecules, primarily proteins, onto the active surfaces of a sensor when it is exposed to complex biological fluids like blood or serum21. OECTs are uniquely susceptible to the detrimental effects of biofouling due to their volumetric operating principle. Unlike traditional transistors, OECTs function by allowing ions from an electrolyte to penetrate and interact with the entire three-dimensional bulk of the OMIEC channel13. While this mechanism is the source of their remarkable sensitivity, it also exposes the entire active volume to fouling, with severe consequences for sensor performance.

The accumulation of charged proteins introduces an uncontrolled surface charge22, causing substantial signal drift and instability that can obscure the target analyte’s signal. This adsorbed layer also acts as a physical barrier, impeding ion flow and slowing device response time while reducing sensitivity5,8,13. Furthermore, biofouling can lead to unreliable results by generating false positive signals from interfering molecules or causing false negatives by blocking the sensor’s specific recognition sites.

Evolving solutions to mitigating biofouling

Similar to the design of other biosensors, addressing the biofouling challenge has been a central theme in OECT research. The solutions have evolved from simple surface passivation toward the design of intrinsically functional materials. These progressions can also be categorized into three tiers.

The first and most basic approach, Tier 1: Simple Surface Passivation, involves pre-coating the sensor with a blocking agent like bovine serum albumin (BSA) to physically occupy the surface5. While simple, this strategy is critically flawed for OECTs. The BSA layer is not covalently bound and is unstable, making it suitable only for single-use offline applications. Most importantly, it cannot be applied to the OMIEC channel surface, as the protein layer would obstruct the ion transport essential for transistor operation.

A more robust approach is Tier 2: Advanced Polymer Coatings. This strategy involves applying specialized antifouling polymers to the sensor surface. Examples include poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG)23, which creates a hydration layer that repels proteins through steric hindrance24, and zwitterionic polymers [e.g., poly(2-methacryloyloxyethyl phosphorylcholine and poly(sulfobetaine methacrylate)], which contain balanced positive and negative charges that bind water molecules with exceptional strength25, forming a powerful energetic and physical barrier to protein adsorption26. In a similar approach, the channel is coated with a protective polymer glue, such as a lithium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide and polyethylene oxide (LiTFSI:PEO) composite, to enhance device stability. This composite layer suppresses destructive oxygen reduction side reactions by acting as a barrier with low water and oxygen permeability27. While these coatings are effective, a key challenge is preventing biofouling without creating a diffusion barrier that can hinder the ion transport necessary for sensor operation23, thereby degrading sensor performance by reducing sensitivity and slowing response time. This inherent conflict motivates the move to the next tier of innovation.

The most advanced and promising solution is Tier 3: Intrinsically Antifouling OMIECs. This state-of-the-art approach resolves the trade-offs of coated systems by building antifouling functionality directly into the conductive material at the molecular level. By covalently attaching antifouling moieties, such as ionic and zwitterionic groups, to the OMIEC monomers before polymerization, a single, monolithic material is created that is simultaneously conductive and bioinert. This eliminates the problematic interface between a coating and the channel, mitigating delamination risks and removing the diffusion barrier that hinders performance. A prime example, phosphorylcholine-functionalized poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT-PC)5, which integrates zwitterionic phosphorylcholine groups into the PEDOT backbone, not only shows outstanding resistance to fouling in undiluted serum but also exhibits enhanced OECT performance metrics compared to its unmodified counterpart.

Another effective strategy involves incorporating ionic groups, such as in carboxylic acid-functionalized polythiophenes28−30. The antifouling mechanism here relies on electrostatic repulsion31. At physiological pH, the carboxylic acid (-COOH) groups deprotonate to form negatively charged carboxylates (-COO–), which repel the many negatively charged proteins and biomolecules present in biofluids32. Moreover, the high biocompatibility of carboxylic acid moieties makes them excellent candidates for in vivo applications. A significant advantage of using such ionic groups is the potential for dynamic, controllable antifouling. Because the net charge depends on the environmental pH, the material properties can be switched33. For instance, a surface with carboxylic acid groups can be configured to resist biofouling at a neutral pH. By intentionally changing to a more acidic pH, the charged groups can be neutralized to allow for the controlled binding of specific targets. This “switchable” functionality offers a more advanced and controllable interface for complex sensing applications. This principle has direct relevance to real-world in vivo applications, drawing parallels from the field of stimuli-responsive drug delivery34. Many pathological microenvironments, such as solid tumors or inflamed tissues, are characterized by a local pH that is more acidic (pH ~6.5) than that of healthy tissues (pH ~7.4)35. An OMIEC device functionalized with pH-responsive polymers could therefore appear inert to healthy tissues but “switch on” its sensing or therapeutic function only upon contacting the target acidic site. Thus, ionic groups can transform the surface of an OMIEC device from a passive barrier to an active, intelligent interface capable of responding to specific biological cues.

Overall, the development of these monolithic, intrinsically antifouling materials has enabled highly sensitive, real-time detection of biomarkers directly in complex biological fluids, representing a crucial step toward the clinical translation of stable and reliable OMIEC-based biosensors.

Opportunities and challenges for specificity, selectivity and sensitivity in OMIEC-based devices

The OMIEC platform possesses several foundational attributes that make it exceptionally well-suited for engineering highly sensitive and selective biosensors. At the material level, the chemical structure of OMIEC polymers can be rationally designed through molecular engineering9,10. Unlike conventional OMIECs that interact only with either cations (n-channel) or anions (p-channel)7, our work shows that polythiophenes functionalized with carboxylic acid sidechains engage with both types of ions28,29. The result indicates that incorporating specific ionic or zwitterionic functionalities can create materials capable of sensing multiple ions in a single polymer format, a feature that promises to enhance biosensing specificity and selectivity when integrated with biorecognition elements. In addition, OMIEC mixed conduction capability and subsequent ionic-electronic coupling result in an exceptionally high transconductance7,13, enabling OMIEC-based bioelectronics to amplify and resolve weak electrochemical signals from specific binding events against a noisy background. Furthermore, the modular transistor configuration of OECTs allows physical separation of the gate electrodes for biofunctionalization without compromising the sensitive channel material. The characteristic low-voltage operation can preserve the delicate structural integrity of recognition molecules like enzymes and antibodies.

The inherent sensitivity of OECTs is often overshadowed by the critical challenge of achieving high specificity36, especially in complex biological fluids37. Because the OECT amplifies any event that changes the local electrochemical potential, interference from non-target molecules can easily mask the desired signal. Therefore, engineering a highly selective recognition interface, typically on the gate electrode, is critical for accurate and reliable sensing.

Biorecognition elements: nature’s lock and key

The most common approach to impart selectivity is to functionalize the sensor with a biological recognition element that has a natural affinity for the target analyte. The common biomolecules include enzymes, antibodies and aptamers. Enzymes, such as glucose oxidase and lactate oxidase have been immobilized on the gate of OECTs for specific redox reaction with their substrates37, producing electrons or a local pH change38. Antibodies are the traditional “gold standard” for detecting proteins and other macromolecules due to their high affinity and specificity39. Demuru et al. integrated the poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene):polystyrene sulfonate (PEDOT:PSS) OECT channel material with cortisol-specific antibodies40, which detects cortisol at concentrations as low as 10 nM in human sweat within 5 min. Both types of biomolecules face the limitation of high costs, batch-to-batch variability, and poor stability under non-physiological conditions.

In the past few decades, synthetic, single-stranded DNA or RNA oligonucleotides that bind to specific targets, i.e., aptamers, have emerged as an alternative to antibodies for many biosensing applications39,41. An example produced by Ji and Rivnay has successfully demonstrated that aptamers are highly promising recognition elements for developing the next generation of reusable and reliable OECT biosensors42. By coupling redox-reporter aptamers specific for TGF-β1 to gold working electrodes that are electronically bridged to a PEDOT:PSS channel, specific binding on the aptamer modulates the OECT gate potential. This mechanism resulted in a remarkable signal gain that is a 103 to 104-fold increase compared to traditional square-wave voltammetry.

Synthetic recognition layers: engineering selectivity

An alternative to using biological molecules is to integrate synthetic biorecognition layers into OMIECs. One example involves ion-selective membranes (ISMs) for selective ion sensing. An ISM is typically a hydrophobic polymer matrix [typically polyvinyl chloride (PVC)] containing a specific ionophore which is a molecule that selectively binds and transports a target ion, such as K+ or Na+43. This selective transport generates a potential at the membrane-analyte interface that is dependent on target ion concentration, which in turn modulates the OECT channel current. In an example produced by Demuru et al.44, an 18-pixel OECT array was assembled by inkjet printing PEDOT:PSS. Each distinct pixel was then functionalized with either a sodium-selective or potassium-selective PVC membrane, along with a pH indicator. The array was subsequently integrated with a microfluidic sweat collection system to produce a complete wearable device. As a result, real-time monitoring on human forearms successfully demonstrated the detection of physiological fluctuations for Na+, K+, and protons (H+). However, the long-term viability of ISMs for in vivo applications is often compromised by stability issues, including poor interfacial adhesion leading to delamination and the leaching of ISM components, which degrade transistor operational performance.

Another example is the incorporation of molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs) into OECT sensors. MIPs are synthetic materials that act as “plastic antibodies”. They are created by polymerizing functional monomers in the presence of a template molecule (the analyte of interest). After polymerization, the template is removed, leaving behind cavities that are complementary in size, shape, and chemical functionality to the target molecule45. This “imprinting” process endows the polymer with a high degree of selectivity. As demonstrated in work by Mehrehjedy and Guo, targets such as cortisol, serotonin, and environmental pollutants were monitored in complex media46. Their work also introduced an enhancement whereby doping the MIP with charged molecules leveraged electrostatic forces to reject charged interferents, thus boosting selectivity. This case illustrates the potential of MIPs in enhancing the selectivity of the OECT biosensors. Further, MIPs are robust, inexpensive to produce, and stable in a wide range of conditions, making them an excellent alternative to biological receptors47.

Innovations in OECT architectures for sensitivity

Aside from the modification of active materials, altering the architecture of OECTs also critically enhances biosensing capabilities. Innovations in device configuration, moving from traditional planar designs to more complex vertical and multi-electrode setups, have proven essential for advancing the sensitivity of OECT biosensors.

A significant advancement is the vertical OECT (vOECT)48, which stacks the source and drain electrodes vertically, dramatically reducing the channel length to the nanoscale thickness of the material layers. This architecture achieves exceptionally high transconductance and current densities, directly boosting the sensitivity of the sensor far beyond that of conventional planar OECTs with a similar footprint. This design has been further adapted into complementary inverters by creating cofacial pairs of vOECTs on a single active area49. This compact arrangement provides significant on-site voltage gain, allowing for direct preamplification of weak biological signals, such as electrocardiograms, at the sensing node.

Another transformative design is the potentiometric-OECT (POECT)50, which reconfigures the gating system to overcome a primary limitation in potentiometric sensing. Traditional OECTs apply current to the sensing gate, preventing it from reaching the thermodynamic equilibrium required for accurate measurements. The POECT architecture innovatively splits the gate into a “sensing gate” and a “gating gate”. This separation maintains the sensing electrode under an open-circuit potential, ensuring that the transistor output is a true and stable amplification of the potentiometric signal. This configuration not only enhances accuracy and response but also allows for the use of high impedance sensing surfaces without compromising device size or stability.

Performance benchmarks of OECT-based biosensors

To contextualize the practical capabilities of OECT biosensors and ground the discussion of their potential in tangible results, it is instructive to survey their performance metrics for detecting key biomarkers in physiologically relevant media. The inherent signal amplification of the OECT architecture translates into impressive analytical performance, often achieving limits of detection in the picomolar to nanomolar range, which is sufficient for many clinical applications. Table 1 compiles key performance metrics, including the limit of detection (LOD), dynamic range, and response time, for a selection of state-of-the-art OECT-based biosensors targeting various analytes.

The data highlight several key trends. For metabolites like glucose and lactate, which are present at relatively high concentrations (mM range) in biofluids, OECT sensors cover clinically relevant dynamic ranges, making them suitable for applications like diabetes management and athletic performance monitoring51. For low-abundance biomarkers such as the stress hormone cortisol or the cytokine TGF-β1, the high transconductance of OECTs enables detection down to the sub-micromolar and even picomolar levels, respectively37,42. Such high sensitivity is critical for early disease diagnosis and monitoring. It is also noteworthy that high performance is increasingly demonstrated not just in simple buffer solutions but also in complex biological matrices like saliva, sweat, and tears, underscoring the progress made in developing robust sensing interfaces. However, maintaining this performance consistently over long periods in complex fluids remains a central challenge, reinforcing the critical importance of the advanced antifouling strategies discussed previously.

The quest for long-term operational stability of OMIEC-based devices

Long-term wearable or implantable sensors require the device to maintain stable functions over weeks, months, or even years. This requirement introduces a new set of challenges related to material- and device-level stability.

Material degradation pathways

The long-term performance of a biosensor is contingent on the stability of its constituent components in the applied environment. The workhorse OMIEC, PEDOT:PSS, has well-documented structural issues related to the insulating PSS component that can compromise its long-term conductivity and performance52. Similarly, some glycolated polythiophenes swell excessively during device operation53,54, which might lead to rapid material degradation. Built on the knowledge of sidechain modification, ion interaction and degradation rate, materials research should prioritize the synthesis of new p- and n-channel OMIECs with greater electrochemical stability and longer operational lifetimes. Such advancements are essential for creating robust devices and complex circuits, including complementary inverters10.

In addition to the materials consideration, electrolyte design is also a topic of active research. For wearable and implantable devices, liquid electrolytes are impractical due to risks of leakage and evaporation. These issues have driven the development of solid-state gel electrolytes, such as hydrogels55. However, these gels face their own challenges, including mechanical degradation under strain, dehydration over time, and delamination from the OMIEC channel. Recent advances in tissue-mimetic hydrogels that are self-healing, stretchable, and possess mechanical properties matching soft biological tissues represent a promising route to address these issues56.

In OMIEC-based biosensors, the biological recognition element such as an enzyme, antibody, or aptamer is often the weakest link57. These delicate biomolecules can denature or be degraded by proteases and nucleases present in the body58,59,60, leading to a gradual loss of sensor selectivity over time. Effective antifouling coatings have been found to not only prevent nonspecific protein binding but also act as a physical shield that protects the immobilized bioreceptors from enzymatic attack, thereby extending their functional lifetime61.

Besides the stability in their final operational environment, material and device integrity during the sterilization process is a critical, yet often overlooked consideration for implantable biosensors62. Standard sterilization methods, such as autoclaving, ethylene oxide gas, and γ-irradiation can be harsh on the sensitive OMIEC materials central to OECT function. Autoclaving, while widely available, can cause macroscopic degradation and cracking in some conductive polymers such as polyaniline63. Conversely, the workhorse OMIEC, PEDOT:PSS, has demonstrated remarkable tolerance to autoclaving, with some studies showing its electrical properties are unharmed by the process62. Some novel OMIECs have even shown improved performance after autoclaving64. Gamma irradiation can cause chain scission and cross-linking in polymers, reducing mechanical and electronic properties, especially at high doses65. Ethylene oxide is a gentler, low-temperature method compatible with most plastics, but concerns about toxic residues and the need for lengthy aeration cycles present their own challenges66. Thus, the choice of sterilization method should be based on the material composition of the device62. These examples highlight another critical dimension of the materials science challenge: developing OMIECs and device architectures that not only perform well in the operational condition, but can also reliably withstand terminal sterilization without compromising function.

Device-level stability and reliability

Beyond the materials themselves, device architecture and integration play a critical role in long-term stability. Robust encapsulation is crucial to protect sensitive components from the corrosive physiological environment without hindering their function. For implanted devices, a key failure mechanism is the foreign body response67, where a mechanical mismatch with soft tissue can cause inflammation and the formation of an insulating glial scar68. Using soft, flexible encapsulation materials is a solution to minimize this reaction. Additionally, sensor drift, changes in signal and sensitivity due to material degradation and biofouling, is a significant challenge for quantitative measurements69. This issue necessitates periodic recalibration, which is difficult for implants. On-chip solutions, such as using reference sensors to subtract drift, are promising strategies for reliable long-term measurement70.

Critically, the stability challenges are inextricably linked. The foreign body response creates a destructive feedback loop that couples biofouling with material degradation. The initial adsorption of proteins onto the implant surface triggers an inflammatory cascade, attracting immune cells like microglia and macrophages71. These activated cells release a host of reactive oxygen species and other corrosive agents in an attempt to break down the foreign object67. This localized, chemically harsh microenvironment can then dramatically accelerate the oxidative degradation of the OMIEC, electrolyte gel, and bioreceptors71. This reveals a deeper truth: an effective antifouling surface is not just a requirement for acute sensing accuracy; it is a prerequisite for achieving long-term material stability in vivo.

Biodegradability for transient and green bioelectronics

Parallel to achieving long-term stability for chronic implants, an emerging and complementary goal is the development of intentionally unstable or biodegradable materials for “transient electronics”72. These are devices engineered to perform a specific function for a predetermined period before safely degrading and being resorbed by the body or the environment73. This paradigm offers significant advantages for certain biomedical applications. For instance, a transient biosensor could monitor a surgical site for signs of infection or track nerve regeneration in the critical weeks following an injury, and then simply dissolve away, eliminating the need for a second, often risky, removal surgery74. This approach is ideal for temporary therapeutic systems, such as bioresorbable pacemakers or electrical stimulators that are only needed during the acute phase of recovery.

From an environmental perspective, biodegradable electronics address the growing problem of electronic waste, aligning with the principles of “green” or sustainable technology72. The foundational challenge lies in designing materials that successfully merge electronic functionality with controlled biodegradability. This requires the incorporation of hydrolytically or enzymatically cleavable bonds (e.g., esters, imines) into the polymer backbone without disrupting the conjugated system required for charge transport72,75. Recent research has demonstrated the feasibility of this approach, with reports of imine-based OMIECs that exhibit both excellent transistor performance and degradable characteristics76. As the field matures, the rational design of biodegradable OMIECs will become an increasingly important research direction, enabling a new class of transient and environmentally benign bioelectronic devices.

Outlook: a roadmap towards translating OMIEC-based biosensors into practice

The journey of the OMIEC-based biosensor from a promising laboratory device to a transformative technology, hinges on mastering the complex interplay at the bio-abiotic interface. The path forward requires a concerted, multidisciplinary effort focused on materials innovation, advanced fabrication, and intelligent system integration (Fig. 3).

The successful clinical translation of OMIEC biosensors requires a multidisciplinary approach that integrates fundamental materials innovation, advanced device optimization and fabrication, and intelligent system-level integration, while also addressing the practical challenges of scalability and regulatory approval.

Challenge 1: fundamentals and material innovation of OMIECs

Mechanistic understanding and multiscale modeling

The advancement of OMIEC-based biosensors is currently hindered by several interconnected challenges. While various OMIEC materials have been demonstrated, the fundamental mechanism of ionic-electronic coupling, the foundational working principle of these materials, remains unclear. This lack of a predictive, holistic understanding forces much of OMIEC research into a slow, case-by-case analysis of different polymer backbone and sidechain combinations. To move beyond empirical approaches, it is necessary to develop a mechanistic understanding of OMIEC materials under device operation. Achieving this goal will require close integration of experimental, computational, and data science approaches. However, OMIECs are extremely challenging from a modeling and computation standpoint given that the local electronic behavior governing local charge distribution and ionic-electronic coupling is intertwined with polymer microstructure and ion transport at the angstrom, nanometer, and micron scales. Thus, any computational approach to understand OMIECs must combine quantum chemistry methods capable of interrogating electronic structure and dynamics with larger-scale classical atomistic and coarse grained methods capable of capturing polymeric structure and assembly77,78,79. The multiscale nature of this problem grows even further when considering OMIEC interactions with biomolecules and the complex bioenvironment. Finally, these multiscale computational techniques must be carefully validated by and/or be directly integrated within experimental efforts. It may be that data-driven methods will be a necessary component to solving these challenges, for example by enabling efficient multiscale simulations and model building80, by providing ways to translate between experimentally- and computationally-produced data81, and by guiding researchers on how to construct information-efficient studies and datasets82.

Hinging on these methodological advancements, an active investigation into the fundamental interactions between dopant ions and various functional groups is in progress. We argue that the field should extend its focus beyond traditional glycolated sidechains to a broader exploration of diverse ionic and zwitterionic functional groups. The mechanistic insight gained will, in turn, enable the development of more robust materials. This approach will also help researchers move beyond simplistic evaluation standards, such as single figures of merit, toward a comprehensive evaluation system that analyzes the full suite of properties, from the conductive performance to biocompatibility and biofunctionality that determine a material’s practical viability. Expansion of the material choices will enable the creation of application-specific devices, where the trade-offs between performance and stability are rationally chosen.

Expanding the materials toolbox: the critical role of n-channel and ambipolar OMIECs

While p-channel OMIECs, particularly PEDOT:PSS, have been the workhorses of the field, the development of high-performance and stable n-channel (electron-conducting) and ambipolar (both electron- and hole-conducting) OMIECs represent a critical frontier for advancing bioelectronic systems83,84. These materials are not merely alternatives to p-channel conductors. They are essential enabling components for creating low-power, complementary logic circuits analogous to the complementary metal oxide semiconductor (CMOS) technology that powers modern electronics85. Such circuits are a prerequisite for sophisticated on-chip data processing, neuromorphic computing, and advanced sensor designs.

The development of n-channel OMIECs has historically lagged behind their p-channel counterparts due to significant materials science challenges. Generally, n-channel materials exhibit inferior stability in aqueous and ambient environments, as their negative charge carriers (polarons) are susceptible to oxidation by water and oxygen84. This fundamental instability necessitates the design of polymers with very low-lying lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) energy levels (typically deeper than −4 eV) to prevent degradation86. Furthermore, n-channel OMIECs often suffer from slower ion injection kinetics and reduced sensitivity in OECTs84. To address these issues, researchers are exploring new molecular design strategies including blending different n-channel polymers to optimize charge transport and morphology84, and engineering novel side chains, such as perfluoroalkyl hybrids, that can effectively repel water from the polymer backbone while still facilitating ion transport84.

Ambipolar OMIECs, which are single materials capable of conducting both holes and electrons, offer a compelling route to simplify the fabrication of complementary circuits by eliminating the need to pattern and integrate separate p- and n-channel materials87. The primary challenge is achieving high and, crucially, balanced performance for both modes of operation88,89. Recent progress has been made through the design of donor-acceptor (D-A) polymer backbones that facilitate both cation and anion injection, leading to ambipolar OECTs with balanced figure-of-merit values and high-gain inverters90,91. The continued innovation in both n-channel and ambipolar OMIECs is therefore a cornerstone for building the next generation of complex, functional bioelectronic systems.

Challenge 2: device optimization for biosensing

The future of OMIEC-based biosensing applications is poised for a significant leap, moving beyond single-analyte detection toward low-cost, high-density, multiplexed arrays. These platforms will provide comprehensive, real-time and continuous measurements of a person’s physiological state. Consequently, the design outlook is shifting from optimizing a single performance metric to a multi-objective, device-level framework. Considering OECT devices, they will not be judged on sensitivity alone but on a balanced scorecard of co-optimized properties. This includes high transconductance for sensitivity, persistent electrochemical and mechanical stability for long-term applications, and, critically, intrinsic antifouling properties that are engineered into the core OMIEC material, not just added as a superficial coating.

Navigating this complex, multi-dimensional design space through traditional, intuition-driven experimentation is slow and inefficient. This challenge can be accelerated by new discovery paradigms that leverage machine learning (ML) and autonomous laboratories to rapidly identify novel materials and device architectures that meet these demanding criteria92. The concept of autonomous, or “self-driving” laboratories, which integrate robotics with AI-driven decision-making, is transforming materials science by enabling high-throughput, closed-loop experimentation.

A powerful example is the “Polybot” system from Argonne National Laboratory, an AI-driven platform that autonomously explores the vast parameter space of electronic polymer processing to fabricate thin films93. By intelligently selecting experiments and analyzing results in real-time, Polybot was able to simultaneously optimize for two competing objectives: high electrical conductivity and low coating defects, achieving state-of-the-art performance far more rapidly than human researchers could.

This autonomous approach is not limited to solid-state materials; it is also revolutionizing the study of soft matter and complex liquid formulations. For instance, the Autonomous Formulation Laboratory (AFL) is an open-source platform designed for the automated synthesis and characterization of liquid mixtures using X-ray and neutron scattering94. The AFL uses a pipetting robot to prepare samples from various stock solutions, enabling the rapid and unattended exploration of complex compositions, such as nanoparticle solutions or surfactant-oil formulations. Its primary goal is to generate the dense, high-quality datasets required to train ML algorithms for mapping phase diagrams and predicting formulation stability, a task that is practically impossible with manual methods due to the vast number of potential compositions.

Although not yet widely adopted for OMIEC discovery, these automated platforms represent a powerful future direction. Guided by ML algorithms, such systems, which can investigate both solid films and liquid solutions, can greatly accelerate the identification of OMIECs with the ideal balance of properties for biosensing.

Challenge 3: system level integration and on-chip intelligence

The future of bioelectronics lies in creating fully integrated, autonomous systems that merge biological sensing, data processing, and therapeutic action. First, OMIEC-based biosensors are achieving remarkable sensitivity in detecting disease biomarkers and neurotransmitters. The primary challenge is transitioning these sensors from controlled lab environments to the complex conditions of the human body while maintaining stability and selectivity.

Second, for true autonomy, these systems require local data processing. In wearable and implantable devices, transmitting raw sensor data to a remote cloud server is often impractical due to high power consumption, latency, and data security concerns. The solution lies in edge computing, where data is processed locally on or near the sensor itself95. This approach is enabled by the integration of machine learning algorithms that can perform complex tasks directly on the sensor output, such as filtering noise, recognizing patterns indicative of a disease state from multiplexed signals, and accurately quantifying analyte concentrations. These intelligent algorithms can replace simple regression models, providing more robust and specific analysis96. The neuromorphic capabilities of OECTs are crucial here, with research demonstrating their use in creating artificial synapses for on-site, low-power analysis of sensor data to recognize disease patterns97. The development of complementary OECT circuits is the foundational hardware step toward building the necessary on-chip processing capabilities to execute these algorithms efficiently.

Finally, OECTs also could function as precise transducers or modulators, controlling the release of therapeutics. While still developing, integrated systems like “smart wound patches” have shown the potential to both sense infection and deliver treatment98. The ultimate goal is a single, biocompatible device that continuously monitors health, determines the need for intervention, and delivers a precise therapeutic dose directly where needed. This closed-loop approach promises highly personalized, timely treatment with minimal side effects, mapping a clear path toward a transformative future in medicine despite remaining challenges.

Challenge 4: navigating scalability and regulatory pathways

While scientific innovation in materials and devices is paramount, the successful translation of OMIEC-based biosensors into clinical practice is ultimately gated by surmounting the practical hurdles of manufacturing and regulation. These non-technical challenges, which constitute the “valley of death” for many promising technologies, must be considered from the earliest stages of research and development99.

A primary challenge is achieving scalable and reproducible manufacturing of high-performance OMIECs. Many conducting polymers suffer from low yield, and small lab-scale synthesis methods7. While high-yield chemical synthesis methods exist, they can introduce impurities that affect device performance, whereas high-purity methods like electro-polymerization have low throughput100. The development of stable, processable dispersions, such as for PEDOT:PSS, has been a key enabler, but achieving consistent batch-to-batch quality for next-generation OMIECs remains an active area of research.

Furthermore, any device intended for clinical use must navigate a complex regulatory landscape. In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) employs a risk-based classification system for medical devices. Devices are categorized as Class I (low risk, e.g., tongue depressors), Class II (moderate risk, e.g., infusion pumps), or Class III (high risk, e.g., pacemakers)101. Most novel OMIEC-based biosensors, particularly those for diagnostics or implants, would likely fall into Class II or III. The regulatory pathway depends on the classification. A Class II device typically requires a Premarket Notification, or 510(k), submission, which demonstrates that the new device is “substantially equivalent” to a legally marketed predicate device. A high-risk Class III device requires a much more stringent Premarket Approval (PMA) application, which must include substantial nonclinical and clinical data to independently establish the device’s safety and effectiveness. The rigorous validation, documentation, and potential for clinical trials demanded by these pathways represent a significant investment of time and resources. Therefore, a holistic “design thinking” approach that incorporates considerations for manufacturing scalability, user needs in a clinical setting, and regulatory requirements from the outset is essential for paving a viable path from the laboratory bench to the patient’s bedside.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

-

Luppa, P. B., Müller, C., Schlichtiger, A. & Schlebusch, H. Point-of-care testing (POCT): Current techniques and future perspectives. Trends Anal. Chem. 30, 887–898 (2011).

-

Sempionatto, J. R., Lasalde-Ramírez, J. A., Mahato, K., Wang, J. & Gao, W. Wearable chemical sensors for biomarker discovery in the omics era. Nat. Rev. Chem. 6, 899–915 (2022).

-

Ohayon, D., Druet, V. & Inal, S. A guide for the characterization of organic electrochemical transistors and channel materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 52, 1001–1023 (2023).

-

Rondelli, F. et al. A single electrode organic neuromorphic device for dopamine sensing in vivo. Adv. Electron. Mater. 10, 2400467 (2024).

-

Zhang, S. et al. Ready-to-use OECT biosensor toward rapid and real-time protein detection in complex biological environments. ACS Sens. 10, 3369–3380 (2025).

-

Rivnay, J. et al. Integrating bioelectronics with cell-based synthetic biology. Nat. Rev. Bioeng. 3, 317–332 (2025).

-

Paulsen, B. D., Tybrandt, K., Stavrinidou, E. & Rivnay, J. Organic mixed ionic–electronic conductors. Nat. Mater. 19, 13–26 (2020).

-

Kim, H. et al. Organic mixed ionic-electronic conductors for bioelectronic sensors: materials and operation mechanisms. Adv. Sci. 11, 2306191 (2024).

-

He, Y., Kukhta, N. A., Marks, A. & Luscombe, C. K. The effect of side chain engineering on conjugated polymers in organic electrochemical transistors for bioelectronic applications. J. Mater. Chem. C. 10, 2314–2332 (2022).

-

Kukhta, N. A., Marks, A. & Luscombe, C. K. Molecular design strategies toward improvement of charge injection and ionic conduction in organic mixed ionic-electronic conductors for organic electrochemical transistors. Chem. Rev. 122, 4325–4355 (2022).

-

Bianchi, M. et al. Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene)-based neural interfaces for recording and stimulation: fundamental aspects and in vivo applications. Adv. Sci. 9, e2104701 (2022).

-

Macchia, E. et al. Organic field-effect transistor platform for label-free, single-molecule detection of genomic biomarkers. ACS Sens. 5, 1822–1830 (2020).

-

Rivnay, J. et al. Organic electrochemical transistors. Nat. Rev. Mater. 3, 17086 (2018).

-

Algarin Perez, A. & Acedo, P. An organic electrochemical transistor-based sensor for IgG levels detection of relevance in SARS-CoV-2 infections. Biosensors 14, 207 (2024).

-

Akhtar, R., Sherratt, M. J., Cruickshank, J. K. & Derby, B. Characterizing the elastic properties of tissues. Mater. Today 14, 96–105 (2011).

-

Yang, W., Gong, Y. & Li, W. A review: electrode and packaging materials for neurophysiology recording implants. Front. Bioeng. Biotech. 8, 622923 (2020).

-

Li, N. et al. Immune-compatible designs of semiconducting polymers for bioelectronics with suppressed foreign-body response. Nat. Mater 25, 124–132 (2026).

-

Dai, Y. et al. Soft hydrogel semiconductors with augmented biointeractive functions. Science 386, 431–439 (2024).

-

Liu, Y., Fan, P., Pan, Y. & Ping, J. Flexible microinterventional sensors for advanced biosignal monitoring. Chem. Rev. 125, 8246–8318 (2025).

-

Abdel Aziz, I. et al. Electrochemical modulation of mechanical properties of glycolated polythiophenes. Mater. Horiz. 11, 2021–2031 (2024).

-

He, Z. et al. Anti-biofouling polymers with special surface wettability for biomedical applications. Front. Bioeng. Biotech. 9, 807357 (2021).

-

Nelson, D. L., Cox, M. M. & Hoskins, A. A. Chapter, 3 Amino Acids, Peptides, and Proteins. In Lehninger Principles of Biochemistry, MacMillan Learning, 8th ed., pp. 71–115 (2021).

-

Campuzano, S., Pedrero, M., Yáñez-Sedeño, P. & Pingarrón, J. M. Antifouling (Bio)materials for Electrochemical (Bio)sensing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 423 (2019).

-

Ham, H. O., Park, S. H., Kurutz, J. W., Szleifer, I. G. & Messersmith, P. B. Antifouling glycocalyx-mimetic peptoids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 13015–13022 (2013).

-

Li, C., Zheng, H., Zhang, X., Pu, Z. & Li, D. Zwitterionic hydrogels and their biomedical applications: a review. Chem. Synthesis 4, 17 (2024).

-

Ma, X., Fu, X. & Sun, J. Preparation of a novel type of zwitterionic polymer and the antifouling PDMS coating. Biomimetics 7, 50 (2022).

-

Zhang, S. et al. Toward stable p-type thiophene-based organic electrochemical transistors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2302249 (2023).

-

Sun, Z. et al. Controlling ion uptake in carboxylated mixed conductors. Adv. Mater. 37, e2414963 (2025).

-

Sun, Z. et al. Carboxyl-alkyl functionalized conjugated polyelectrolytes for high performance organic electrochemical transistors. Chem. Mater. 35, 9299–9312 (2023).

-

Sun, Z. et al. pH Regulates Ion Dynamics in Carboxylated Mixed Conductors. arXiv2511.09671, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2511.09671 (2025).

-

Chen, S., Li, L., Zhao, C. & Zheng, J. Surface hydration: Principles and applications toward low-fouling/nonfouling biomaterials. Polymer 51, 5283–5293 (2010).

-

Voet, D., Voet, J. G. & Pratt, C. W. Fundamentals of Biochemistry: Life at the Molecular Level (Wiley, 2016).

-

Singh, J. & Nayak, P. pH-responsive polymers for drug delivery: trends and opportunities. J. Polym. Sci. 61, 2828–2850 (2023).

-

Stuart, M. A. C. et al. Emerging applications of stimuli-responsive polymer materials. Nat. Mater. 9, 101–113 (2010).

-

Webb, B. A., Chimenti, M., Jacobson, M. P. & Barber, D. L. Dysregulated pH: a perfect storm for cancer progression. Nat. Rev. Cancer 11, 671–677 (2011).

-

Niu, Y. et al. Expanding the potential of biosensors: a review on organic field effect transistor (OFET) and organic electrochemical transistor (OECT) biosensors. Mater. Fut. 2, 042401 (2023).

-

Gualandi, I. et al. Layered double hydroxide-modified organic electrochemical transistor for glucose and lactate biosensing. Sensors 20, 3453 (2020).

-

Lin, Y., Kroon, R., Zeglio, E. & Herland, A. P-type accumulation mode organic electrochemical transistor biosensor for xanthine detection in fish. Biosens. Bioelectron. 269, 116928 (2025).

-

Reano, R. L. & Escobar, E. C. A review of antibody, aptamer, and nanomaterials synergistic systems for an amplified electrochemical signal. Front. Bioeng. Biotech. 12, 1361469 (2024).

-

Demuru, S. et al. Antibody-coated wearable organic electrochemical transistors for cortisol detection in human sweat. ACS Sens. 7, 2721–2731 (2022).

-

Strehlitz, B., Nikolaus, N. & Stoltenburg, R. Protein detection with aptamer biosensors. Sensors 8, 4296–4307 (2008).

-

Ji, X., Lin, X. & Rivnay, J. Organic electrochemical transistors as on-site signal amplifiers for electrochemical aptamer-based sensing. Nat. Commun. 14, 1665 (2023).

-

Wang, Z. et al. Functional organic electrochemical transistor-based biosensors for biomedical applications. Chemosensors 12, 236 (2024).

-

Demuru, S., Kunnel, B. P. & Briand, D. Real-time multi-ion detection in the sweat concentration range enabled by flexible, printed, and microfluidics-integrated organic transistor arrays. Adv. Mater. Technol. 5, 2000328 (2020).

-

Agar, M., Laabei, M., Leese, H. S. & Estrela, P. Multi-template molecularly imprinted polymeric electrochemical biosensors. Chemosensors 13, 11 (2025).

-

Mehrehjedy, A. et al. Selective and sensitive OECT sensors with doped MIP-modified GCE/MWCNT gate electrodes for real-time detection of serotonin. ACS Omega 10, 4154–4162 (2025).

-

Pilvenyte, G. et al. Molecularly imprinted polymer-based electrochemical sensors for the diagnosis of infectious diseases. Biosensors 13, 620 (2023).

-

Huang, W. et al. Vertical organic electrochemical transistors for complementary circuits. Nature 613, 496–502 (2023).

-

Rashid, R. B. et al. Ambipolar inverters based on cofacial vertical organic electrochemical transistor pairs for biosignal amplification. Sci. Adv. 7, eabh1055 (2021).

-

Salvigni, L. et al. Reconfiguration of organic electrochemical transistors for high-accuracy potentiometric sensing. Nat. Commun. 15, 6499 (2024).

-

Meng, K. et al. Nanostructure-gated organic electrochemical transistors for accurate glucose monitoring in dynamic biological pH conditions. Biosens. Bioelectron. 287, 117677 (2025).

-

Taniguchi, H., Nagata, M., Yano, H., Okuzaki, H. & Takeoka, S. Evaluation of stability and cytotoxicity of self-doped PEDOT nanosheets in a quasi-biological environment for bioelectrodes. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 6, 1645–1652 (2024).

-

Nicolini, T. et al. A low-swelling polymeric mixed conductor operating in aqueous electrolytes. Adv. Mater. 33, e2005723 (2021).

-

Schmode, P. et al. The key role of side chain linkage in structure formation and mixed conduction of ethylene glycol substituted polythiophenes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 13029–13039 (2020).

-

Lu, D. & Chen, H. Solid-state organic electrochemical transistors (OECTs) based on gel electrolytes for biosensors and bioelectronics. J. Mater. Chem. A 13, 136–157 (2025).

-

Yao, X. et al. Super stretchable, self-healing, adhesive ionic conductive hydrogels based on tailor-made ionic liquid for high-performance strain sensors. Adv. Func. Mater. 32, 2304565 (2022).

-

McCann, B. et al. A review on perception of binding kinetics in affinity biosensors: challenges and opportunities. ACS Omega 10, 4197–4216 (2025).

-

Zhou, J. & Rossi, J. Aptamers as targeted therapeutics: current potential and challenges. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 16, 181–202 (2017).

-

Sun, G. et al. Immobilization of enzyme electrochemical biosensors and their application to food bioprocess monitoring. Biosensors 13, 886 (2023).

-

Khongorzul, P., Ling, C. J., Khan, F. U., Ihsan, A. U. & Zhang, J. Antibody–drug conjugates: a comprehensive review. Mol. Cancer Res. 18, 3–19 (2020).

-

Wang, S., Liu, Y., Zhu, A. & Tian, Y. In vivo electrochemical biosensors: recent advances in molecular design, electrode materials, and electrochemical devices. Anal. Chem. 95, 388–406 (2023).

-

Uguz, I. et al. Autoclave sterilization of PEDOT:PSS electrophysiology devices. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 5, 3094–3098 (2016).

-

Yan, Y. et al. Impact of sterilization on a conjugated polymer based bioelectronic patch. bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.01.19.427349 (2021).

-

Liao, H. et al. High performance organic mixed ionic-electronic polymeric conductor with stability to autoclave sterilization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202416288 (2025).

-

Ferrante, C. et al. Gamma irradiation effect on polymeric chains of epoxy adhesive. Polymers 16, 1202 (2024).

-

Tipnis, N. P. & Burgess, D. J. Sterilization of implantable polymer-based medical devices: a review. Int. J. Pharmaceutics 544, 455–460 (2018).

-

Carnicer-Lombarte, A., Chen, S. T., Malliaras, G. G. & Barone, D. G. Foreign body reaction to implanted biomaterials and its impact in nerve neuroprosthetics. Front. Bioeng. Biotech. 9, 622524 (2021). article.

-

Janmey, P. A., Fletcher, D. A. & Reinhart-King, C. A. Stiffness sensing by cells. Physiol. Rev. 100, 695–724 (2020).

-

Han, X.-L. et al. Integrated perspective on functional organic electrochemical transistors and biosensors in implantable drug delivery systems. Chemosensors 13, 215 (2025).

-

Bai, L. et al. Biological applications of organic electrochemical transistors: electrochemical biosensors and electrophysiology recording. Front. Chem. 7-2019, 313 (2019).

-

Golabchi, A., Wu, B., Cao, B., Bettinger, C. J. & Cui, X. T. Zwitterionic polymer/polydopamine coating reduce acute inflammatory tissue responses to neural implants. Biomaterials 225, 119519 (2019).

-

Bae, J.-Y., Choi, M.-K. & Kang, S.-K. Transient electronics for sustainability: emerging technologies and future directions. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 16, 1545–1556 (2025).

-

Zhai, Z., Du, X., Long, Y. & Zheng, H. Biodegradable polymeric materials for flexible and degradable electronics. Front. Electron. 3, 985681 (2022). article.

-

Li, R., Wang, L., Kong, D. & Yin, L. Recent progress on biodegradable materials and transient electronics. Bioact. Mater. 3, 322–333 (2018).

-

Feig, V. R., Tran, H. & Bao, Z. Biodegradable polymeric materials in degradable electronic devices. ACS Cent. Sci. 4, 337–348 (2018).

-

Chen, J. et al. Imine-based polymeric mixed ionic–electronic conductors featuring degradability and biocompatibility for transient bioinspired electronics. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202417921 (2025).

-

Khot, A. & Savoie, B. M. Top–down coarse-grained framework for characterizing mixed conducting polymers. Macromolecules 54, 4889–4901 (2021).

-

Wang, C.-I. & Jackson, N. E. Bringing quantum mechanics to coarse-grained soft materials modeling. Chem. Mater. 35, 1470–1486 (2023).

-

Gartner, T. E. & Jayaraman, A. Modeling and simulations of polymers: a roadmap. Macromolecules 52, 755–786 (2019).

-

Jackson, N. E., Savoie, B. M., Statt, A. & Webb, M. A. Introduction to machine learning for molecular simulation. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 19, 4335–4337 (2023).

-

Patel, R. A. & Webb, M. A. Data-driven design of polymer-based biomaterials: high-throughput simulation, experimentation, and machine learning. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 7, 510–527 (2024).

-

Martin, T. B. & Audus, D. J. Emerging trends in machine learning: a polymer perspective. ACS Polym. Au 3, 239–258 (2023).

-

Zhang, Y. et al. Adaptive biosensing and neuromorphic classification based on an ambipolar organic mixed ionic–electronic conductor. Adv. Mater. 34, 2200393 (2022).

-

Griggs, S., Marks, A., Bristow, H. & McCulloch, I. n-Type organic semiconducting polymers: stability limitations, design considerations and applications. J. Mater. Chem. C. 9, 8099–8128 (2021).

-

Uguz, I. et al. Complementary integration of organic electrochemical transistors for front-end amplifier circuits of flexible neural implants. Sci. Adv. 10, 9710 (2024). eadi.

-

Jackson, S. R., Collins, G. W., Phan, T. D. U., Ponder, J. F. & Bischak, C. G. Enhancing N-type organic electrochemical transistor performance via blending alkyl and oligoglycol functionalized polymers. Adv. Mater. 37, e05963 (2025).

-

Stein, E. et al. Synergistic effects in ambipolar blends of mixed ionic–electronic conductors. Mater. Horiz. 12, 5733–5748 (2025).

-

Gao, D., van der Pol, T. P. A., Musumeci, C., Tu, D. & Fabiano, S. Organic mixed conductors for neural biomimicry and biointerfacing. Annu. Rev. Chem. Biomol. Eng. 16, 293–320 (2025).

-

Moscovich, N. et al. Balanced ambipolar OECTs through tunability of blend microstructure. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 17, 43327–43338 (2025).

-

Qi, G. et al. High-performance, single-component ambipolar organic electrochemical transistors with balanced n/p-type properties for inverter and biosensor applications. Adv. Func. Mater. 35, 2413112 (2024).

-

Pan, X. et al. Strong proquinoidal acceptor enables high-performance ambipolar organic electrochemical transistors. Adv. Mater. 37, e2417146 (2025).

-

Madika, B. et al. Artificial intelligence for materials discovery, development, and optimization. ACS Nano 19, 27116–27158 (2025).

-

Wang, C. et al. Autonomous platform for solution processing of electronic polymers. Nat. Commun. 16, 1498 (2025).

-

Beaucage, P. A. & Martin, T. B. The autonomous formulation laboratory: an open liquid handling platform for formulation discovery using X-ray and neutron scattering. Chem. Mater. 35, 846–852 (2023).

-

Satyanarayanan, M. The emergence of edge computing. Computer 50, 30–39 (2017).

-

Schackart, K. E. & Yoon, J.-Y. Machine learning enhances the performance of bioreceptor-free biosensors. Sensors 21, 5519 (2021).

-

Esmaeili, F. et al. Utilizing deep learning algorithms for signal processing in electrochemical biosensors: from data augmentation to detection and quantification of chemicals of interest. Bioengineering 10, 1348 (2023).

-

Derakhshandeh, H., Kashaf, S. S., Aghabaglou, F., Ghanavati, I. O. & Tamayol, A. Smart bandages: the future of wound care. Trends Biotechnol. 36, 1259–1274 (2018).

-

Docherty, N. et al. Maximising the translation potential of electrochemical biosensors. Chem. Commun. 61, 13359–13377 (2025).

-

Inzelt, G. Chemical and electrochemical syntheses of conducting polymers. In Conducting Polymers: A New Era in Electrochemistry, 149–171 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2012).

-

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Overview of Medical Device Regulation. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/device-advice-comprehensive-regulatory-assistance/overview-medical-device-regulation (2024) (accessed October 9, 2025).

-

Sun, Y. et al. MOF-MoS2 nanosheets doped PEDOT:PSS for organic electrochemical transistors in enhanced glucose sensing and machine learning-based concentration prediction. Mater. Fut. 4, 025302 (2025).

-

Parlak, O., Keene, S. T., Marais, A., Curto, V. F. & Salleo, A. Molecularly selective nanoporous membrane-based wearable organic electrochemical device for noninvasive cortisol sensing. Sci. Adv. 4, eaar2904 (2018).

-

Deng, Z. et al. Recyclable semiconductor aerogel electrochemical transistors for ultrasensitive biosensors. Nano Lett. 25, 14928–13937 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge support in the form of non-federal funds from Lehigh University and the Lehigh Rossin College of Engineering under the auspices of the Rossin Innovation Grant Program, the Institute for Functional Materials and Devices, and funds associated with the Carl Robert Anderson Chair in Chemical Engineering. E.R., T.E.G., S.Q., and C.R. also acknowledge partial support from the National Science Foundation, Division of Materials Research Grant No. 2408881.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Qin, S., Sun, Z., Sun, S. et al. Organic mixed ionic-electronic conductor device platforms for emerging biosensor application. npj Biosensing 3, 10 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44328-025-00072-9

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

Version of record:

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44328-025-00072-9