replying to S. Collin & K. J. Weissman. Nature Communications https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61435-4 (2025)

We are glad that Collin and Weissman1 consider that our approach of splitting the genes encoding multi-modular polyketide synthases (PKSs) within an operon into smaller fragments represents a promising means to the field of PKS engineering. In the following, we reply to Collin and Weissman’s1 insightful comments on the orthogonality of docking domains (DDs) employed in our method to split PKSs into shorter proteins. Weissman and coworkers have published seminal studies on the interactions of PKS DDs, the structural basis of docking selectivity, and the classification of DDs2,3,4,5. Collin and Weissman point out an inaccurate statement “docking domains do not enhance the communication and activity of modular PKSs.” Here, we acknowledge that the previous statement was misleading and concur with their view that DDs indeed enhance the communication of PKS subunits. Collin and Weissman further point out that the seminal work conducted by Yan and coworkers6, which functionally dissected a multi-modular PKS into monomodules by using a matched pair of heterologous DDs, was not cited. Here, we also acknowledge this and highlight this work in this Reply.

Collin and Weissman1 comment on the importance of considering DD orthogonality in our PKS splitting approach to maintain the proper ordering of the subunits and prevent aberrant cross-talk occurring between the introduced and native DDs. We agree with this and endorse their assertion that DDs used for splitting PKSs should be orthogonal to those natively present in the system. The primary objective of our study7 was to investigate the impact of mRNA truncation on PKS protein expression, and to develop strategies for rescuing the translation of truncated mRNAs into functional PKS subunits, ultimately enhancing polyketide biosynthesis. Consequently, we did not comprehensively describe the DD types and orthogonality in our initial investigation.

Although amino acid sequence analysis provides a means to assess DD orthogonality, it sometimes diverges from the experimental outcomes. For example, as indicated by Collin and Weissman1, detailed inspection of the twelve charged and hydrophobic residues that make up the interface in DD pairs reveals that both type 1a SlnA1 CDD (DLIEL, charged residues potentially contribute to complex formation are italicized) and SlnA7 CDD (DFLEL) could be compatible with type 1a BusD NDD (KYLVTLH), and reciprocally, that the BusC CDD (DFIEL) could potentially interact with either SlnA2 NDD (KSLVALH) or SlnA8 NDD (KYLATLR) (Fig. 2d (Collin and Weissman1)). Based on this analysis, it seems plausible that type 1a PikAII CDD (DFIEL) (Supplementary Fig. 1 (Collin and Weissman1)) could be compatible with type 1a DEBS2 NDD (KSLATLR) (Supplementary Table 1), and reciprocally, BEBS1 CDD (DLLEL) (Supplementary Table 1) could potentially interact with PikAIII NDD (KYLVTLQ) (Supplementary Fig. 1 (Collin and Weissman1)). However, contrary to these predictions, Buchholz et al. conducted systematic surface plasmon resonance binding assays which demonstrated that BEBS1 CDD does not interact with PikAIII NDD, and PikAII CDD does not interact with DEBS2 NDD either8.

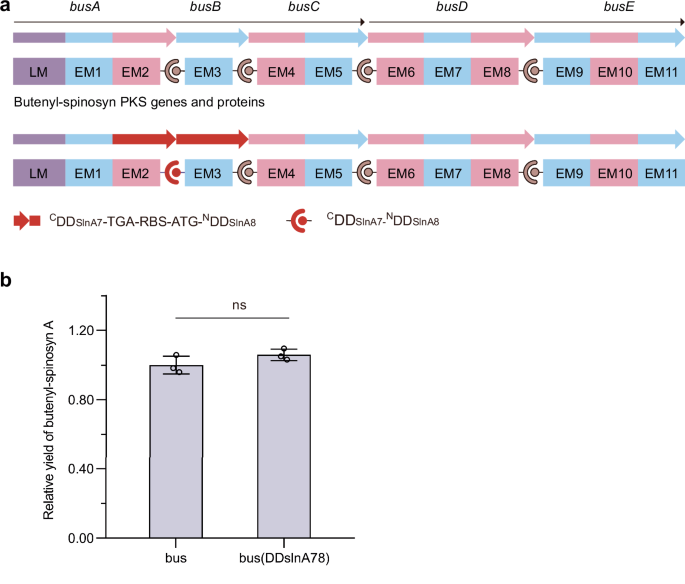

To evaluate the impact of introducing exogenous DDs of the same type as the remaining native DDs on polyketide biosynthesis, we substituted type 1b BusA CDD/BusB NDD with either type 1a SlnA1 CDD/SlnA2 NDD (Supplementary Fig. 3 (Liu et al.7)) or SlnA7 CDD/SlnA8 NDD (Fig. 1). This substitution was based on the observation that SlnA1 CDD and SlnA7 CDD share the same key charged residues as BusC CDD, which contribute to PKS complex formation. If aberrant cross-talk occurs between the introduced SlnA1 CDD or SlnA7 CDD and the native BusD NDD, or between the native BusC CDD and the introduced SlnA2 NDD or SlnA8 NDD, it could result in alternative products or stalled assembly lines, both of which would reduce yields of butenyl-spinosyn. To investigate this, butenyl-spinosyn gene clusters containing either the wild-type or the exchanged DD coding sequences were transformed into Streptomyces albus J1074, and butenyl-spinosyn A production by the transformants was analyzed. The results showed that the above exchanges did not affect the butenyl-spinosyn biosynthesis (Supplementary Fig. 3 (Liu et al.7) and Fig. 1). Consequently, we conclude that the orthogonality of SlnA1 CDD/SlnA2 NDD and SlnA7 CDD/SlnA8 NDD within the butenyl-spinosyn PKSs is good. Because the above DD exchanges did not affect butenyl-spinosyn biosynthesis, we did not attempt to search for products potentially arising from incorrect associations. We acknowledge that, if we did, our conclusions could be further enhanced. Notably, the differences between the native AveA PKSs or Epo PKSs and the introduced exogenous DD pairs are more substantial across the key residues; therefore, we did not evaluate the impact of their introduction on avermectin and epothilone biosynthesis.

a The strategy used to substitute the CDD of BusA with that of SlnA7 and the NDD of BusB with that of SlnA8. b Butenyl-spinosyn A production by S. albus J1074 strains harboring gene clusters containing the wild-type or exchanged docking domain coding sequences. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 8.0.1 software and a two-tailed unpaired t-test. The p values less than 0.05 were considered significant. n = 3 independent fermentation samples. Data are presented as the mean ± S.D. ns not significant.

It is possible that the DDs selected for transplant may misassociate with native DDs elsewhere in the recipient PKS. Collin and Weissman provide concise guidelines for selecting orthogonal pairs of DDs. Additionally, it has been demonstrated that some subunits of protein complexes interact with each other as they are being translated within the ribosome, a process termed cotranslational assembly, which occurs in both bacterial9 and eukaryotic cells10. Cotranslational assembly process in bacteria is favored by operons that encode the subunits of protein complexes, such as the heteromeric luciferase complex in Escherichia coli9. Assembly of the heterodimeric LuxAB luciferase complex requires ribosome-associated exposure of the N-terminal dimer interface of LuxB. When the Lux subunits are translated from messenger RNAs transcribed from genes situated at distant loci on the E. coli chromosome, the assembly efficiency decreases markedly. The organization of genes encoding the subunits of protein complexes adjacent to one another within an operon promotes their colocalized synthesis and assembly. Notably, genes encoding multi-modular PKSs are frequently organized in operons in bacteria. Currently, it is not known if PKS megasynthase complexes are formed through cotranslational assembly. If the ordered arrangement of PKS genes within an operon has evolved to promote cotranslational assembly of PKS subunits, the orthogonality of cognate DD pairs would be further ensured in vivo. Investigating this intriguing possibility represents a promising avenue for future research.

Methods

Exchange of BusA CDD/BusB NDD with SlnA7 CDD/SlnA8 NDD

The BusA CDD/BusB NDD coding sequence within the butenyl-spinosyn gene cluster in pBAC11-phiC31-bus7 was replaced with the SlnA7 CDD/SlnA8 NDD coding sequence (Fig. 1) using the RedEx seamless mutagenesis method7. The templates and oligonucleotides used for preparation of the RedEx cassette, HAL-CDDslnA78-TGA-RBS-ATG-NDDslnA78-HAR20-PacI-ampccdB-PacI-HAR, by overlap extension PCR are listed in Supplementary Table 2. The RedEx cassette was inserted into pBAC11-phiC31-bus through recombineering in E. coli GBred-gyrA462 to obtain pBAC-phiC31-busAB-ampccdB. The PacI-digested pBAC-phiC31-busAB-ampccdB was reacted in 1 × ABclonal MultiF Seamless Assembly Mix (ABclonal, cat. no. RK21020) and then electroporated into E. coli GB2005 to obtain pBAC11-phiC31-busAB SlnA78.

Analysis of butenyl-spinosyn production in the S. albus J1074 strains

Fermentation of S. albus J1074 strains, and high-performance liquid chromatography−mass spectrometry analysis of butenyl-spinosyn A was performed according to the procedure described by Liu et al.7. Briefly, the S. albus J1074 strains harboring the wild-type or recombinant butenyl-spinosyn gene clusters were incubated at 30 °C with shaking at 220 rpm for 7 days in 250-mL flasks containing 30 mL of fermentation broth (4% glucose, 1% glycerol, 3% soluble starch, 1.5% soytone, 1% beef extract, 0.05% yeast extract, 0.1% magnesium sulfate, 0.24% CaCO3, 0.2% NaCl, and 0.65% peptone). Upon the addition of Amberlite XAD-16 adsorber resin, the culture underwent further incubation for 2 days. The cultures were centrifuged to pellet the cells and Amberlite XAD-16. The pellet was extracted with methanol and then used for HPLC-MS analysis. The HPLC mobile phase solvent A was H2O containing 0.1% (v/v) formic acid. The mobile phase solvent B was acetonitrile containing 0.1% (v/v) formic acid. HPLC analysis was performed on an Ultimate 3000 UHPLC-DAD system (Thermo Fisher Scientific) equipped with an Acclaim RSLC 120 C18 column (2.2 m, 2.1 × 100 mm, Thermo Scientific) at a UV wavelength of 200–600 nm and a flow rate of 0.3 mL min−1. The mass spectrometric analysis was performed on an Impact HD micro TFF-Q III mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) using a standard ESI source operating in centroid mode (100–1500 m/z) with positive ionization mode and automatic MS2 fragmentation.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of this work are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information files. A reporting summary for this article is available as a Supplementary Information file.

References

-

Collin, S. & Weissman, K. J. Docking domains from modular polyketide synthases and their use in engineering. Nat. Commun. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61435-4 (2025).

-

Broadhurst, R. W., Nietlispach, D., Wheatcroft, M. P., Leadlay, P. F. & Weissman, K. J. The structure of docking domains in modular polyketide synthases. Chem. Biol. 10, 723–731 (2003).

-

Weissman, K. J. The structural basis for docking in modular polyketide biosynthesis. ChemBioChem 7, 485–494 (2006).

-

Risser, F. et al. Towards improved understanding of intersubunit interactions in modular polyketide biosynthesis: Docking in the enacyloxin IIa polyketide synthase. J. Struct. Biol. 212, 107581 (2020).

-

Richter, C. D., Nietlispach, D., Broadhurst, R. W. & Weissman, K. J. Multienzyme docking in hybrid megasynthetases. Nat. Chem. Biol. 4, 75–81 (2008).

-

Yan, J., Gupta, S., Sherman, D. H. & Reynolds, K. A. Functional dissection of a multimodular polypeptide of the pikromycin polyketide synthase into monomodules by using a matched pair of heterologous docking domains. ChemBioChem 10, 1537–1543 (2009).

-

Liu, Y. et al. Improving polyketide biosynthesis by rescuing the translation of truncated mRNAs into functional polyketide synthase subunits. Nat. Commun. 16, 774 (2025).

-

Buchholz, T. J. et al. Structural basis for binding specificity between subclasses of modular polyketide synthase docking domains. ACS Chem. Biol. 4, 41–52 (2009).

-

Shieh, Y. W. et al. Operon structure and cotranslational subunit association direct protein assembly in bacteria. Science 350, 678–680 (2015).

-

Mallik, S. et al. Structural determinants of co-translational protein complex assembly. Cell 188, 764–777.e22 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge financial support from the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR2022JQ11 to H.W.) and the Fundamental Research Funds of Shandong University (2023QNTD001 to H.W.).

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Y., Wang, H. Reply to: Docking domains from modular polyketide synthases and their use in engineering. Nat Commun 16, 6689 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61436-3

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61436-3