Introduction

The CRISPR-Cas9 system, originally derived from the bacterial adaptive immune defense, has emerged as a versatile genome-editing tool, enabling precise and efficient genetic modifications across diverse organisms1,2,3. Among the CRISPR-Cas9 systems, Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9) has been the most extensively characterized, both structurally and functionally, to elucidate its molecular mechanism. Guided by a programmable chimeric single-guide RNA (sgRNA), SpCas9 selectively targets specific DNA sequences4. The SpCas9–sgRNA complex scans the genome for a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM), a short DNA sequence essential for target recognition5,6. Upon PAM recognition, SpCas9 induces local DNA unwinding, allowing the sgRNA to base-pair with the target DNA7,8. This event triggers the introduction of double-strand breaks (DSBs), subsequently repaired by cellular pathways such as non-homologous end joining or homology-directed repair, resulting in gene knock-out or knock-in events9. Owing to these capabilities, CRISPR-Cas9 has become an extensively studied and utilized tool in basic biological research, biotechnology, and gene therapy10. Leveraging the sgRNA-mediated DNA targeting capability of Cas9, researchers have extensively engineered the protein to broaden its range of applications11,12,13,14. One common strategy involves fusing functional domains to the N- or C- terminus of SpCas9 to endow additional functionalities15,16. For instance, fusion with base-editing enzymes enables site-specific nucleotide conversions without introducing DSBs. Cytosine base editors (CBEs) and adenine base editors (ABEs) enable C-to-T and A-to-G conversions, respectively17,18. One such engineered SpCas9 variant, ABE8e, features an evolved tRNA adenosine deaminase (TadA8e) fused to the N-terminus of SpCas919. However, these terminal fusions often require long and flexible linkers, which can increase the overall size of the construct and hinder delivery efficiency—especially in therapeutic contexts20. To overcome these limitations, alternative strategies have explored inserting functional domains into internal regions of SpCas9. One study adopted a systematic approach to identify an optimal insertion site by incorporating the human estrogen receptor-α ligand-binding domain (ER-LBD), yielding an allosterically regulated SpCas9 variant21. Another approach replaced the HNH domain with TadA7.10 to construct a compact SpCas9 base editor18,22. However, it remains unclear whether insertion or replacement of the internal region compromises the structural integrity or activity of SpCas9, as this has not been thoroughly evaluated at the molecular level.

SpCas9 consists of two main lobes: the recognition (REC) lobe and the nuclease (NUC) lobe. The REC lobe, subdivided into three distinct domains (REC1, REC2, and REC3), is critical for recognizing and binding sgRNA and target DNA23,24. The NUC lobe contains the C-terminal domain (CTD) and two nuclease domains, RuvC and HNH, which are responsible for cleaving the non-target and target DNA strands, respectively. The CTD, which includes the PAM-interacting (PI) domain and the wedge domain, plays an important role in PAM recognition6,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33. In addition, the CTD mediates non-specific interactions with the DNA duplex and contributes to the initial unwinding of the double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) in various Cas9 homologs, including SpCas9, Francisella novicida Cas9 (FnCas9), Staphylococcus aureus Cas9 (SaCas9), and Geobacillus stearothermophilus Cas9 (GeoCas9)6,7,25,32,34. Notably, the CTD exhibits substantial variability in length, architecture, and PAM recognition across Cas9 homologs (Supplementary Fig. S1, S2). For instance, although SpCas9 and FnCas9 both recognize the same 5ʹ-NGG-3ʹ PAM sequence, their CTDs show significant structural differences25. Even the two closely related orthologs of Neisseria meningitidis Cas9 (Nme1Cas9 and Nme2Cas9) diverge in CTD structure and PAM specificity, highlighting its modularity and rapid evolutionary adaptation35.Thus, the CTD represents a structurally and functionally flexible region and an attractive target for engineering.

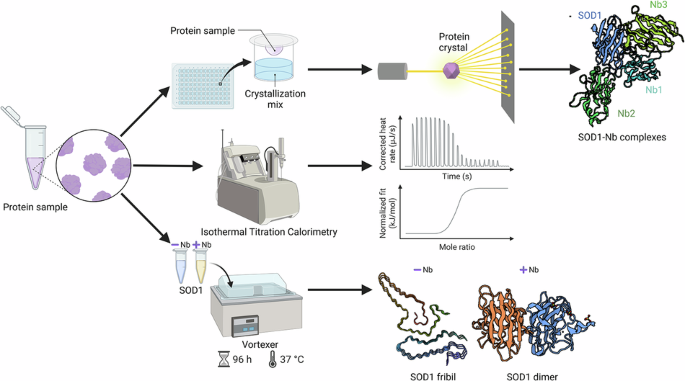

In this study, we aimed to identify internal regions of SpCas9 that could be replaced with foreign domains without disrupting the overall structure and function of SpCas9. By analyzing previously reported structures of SpCas96,36,37 and examining sequence conservation across Cas9 homologs, we identified a CTD segment (residues 1242–1263) that could be deleted without impairing the function and structural integrity of SpCas9. This was confirmed by in vitro functional assays and structure determination of the deletion variant of SpCas9 (Cas9ΔCTD22). Our results suggest that the 1242–1263 region can be replaced with a foreign functional domain. As a proof of concept, we replaced this region with TadA8e—a widely used ABE—and confirmed adenosine deaminase activity in the resulting SpCas9 variants.

Results

Design of SpCas9 variant with internal deletion

Comparative analysis of multi-domain structures from various Cas9 homologs reveals significant variations in domain lengths and amino acid sequences (Supplementary Fig. S1)25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,36. Notably, the CTD exhibits substantial divergence in amino acid composition among Cas9 homologs. Structural analysis demonstrates that the structural elements constituting the CTD vary considerably, and the regions involved in the key function of PAM recognition are also distinct (Supplementary Fig. S1, S2)6,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33. These observations suggest that the CTD is structurally and functionally diverse region among Cas9 homologs, potentially amenable to modification.

To identify a suitable site for domain insertion, we closely examined the CTD of SpCas9 in previously reported ternary complex structures. We focused on the segment spanning residues Y1242–K1263, which consists of a flexible linker and an α-helix (Fig. 1a). This region does not form extensive contacts with adjacent structural elements or the non-target strand (NTS), and lacks a clearly defined functional role36. Moreover, sequence alignment across Cas9 homologs indicates that this segment is entirely unconserved25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,36. Based on these observations, we hypothesized that substitution or deletion of this region would not disrupt the structural integrity or function of SpCas9.

Design and in vitro functional evaluation of Cas9ΔCTD22 (a) Structural representation of the 1242–1263 region in SpCas9, based on the ternary complex structure (PDB ID: 7Z4I). The SpCas9 ternary complex is depicted in a cartoon representation, with a black box indicating the zoomed-in region that highlights the 1242–1263 region. Both cartoon and transparent surface representations illustrate that the 1242–1263 region does not form substantial interactions with surrounding structural elements. SpCas9 is shown in gray, with the 1242–1263 region highlighted in slate, the target strand (TS) and the non-target strand (NTS) are shown in cyan and yellow, respectively, and the sgRNA in orange. (b) Schematic representation of the Cas9ΔCTD22 construct. (c) In vitro DNA cleavage assays comparing the activity of wild-type SpCas9 and Cas9ΔCTD22 using Cy5-labeled DNA. (d) Representative EMSA results for binding to TGG PAM-containing DNA. (e) Quantitative analysis of EMSA data for dCas9 and dCas9ΔCTD22 binding to TGG PAM DNA. Binding fractions were calculated based on the intensity of free and shifted bands. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (S.E.M.). Statistical data are summarized in Supplementary Table S2. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

To test this hypothesis, we generated a deletion mutant, Cas9ΔCTD22, in which residues 1242–1263 were replaced with a short glycine-serine (GSGSGSG) linker (Fig. 1b). This deletion mutant was overexpressed in E. coli and purified to homogeneity using size-exclusion chromatography (SEC). The SEC profile of this mutant closely resembled that of wild-type SpCas9, suggesting that the deletion did not compromise proper folding and that the mutant does not exhibit signs of structural misfolding or aggregation (Supplementary Fig. S3).

The 1242–1263 region is dispensable for SpCas9 activity

To evaluate whether the 1242–1263 region is essential for SpCas9 function, we first assessed the DNA cleavage activity of the Cas9ΔCTD22 variant using fluorescently labeled dsDNA containing either a canonical TGG or a non-canonical TTG PAM sequence. The results demonstrated that both SpCas9 and Cas9ΔCTD22 exhibited comparable cleavage activity toward dsDNA containing a TGG PAM sequence (Fig. 1c). As expected, both proteins showed reduced activity against the TTG PAM substrate, consistent with the lower efficiency of non-canonical PAM recognition.

To assess the binding affinity of Cas9ΔCTD22 to a canonical PAM sequence, we carried out an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) using Cy5-labeled dsDNA. In this assay, DNA concentration was fixed at 10 nM, and the fraction of shifted DNA bands was measured as the concentration of ribonucleoprotein increased from 2.5 nM to 1,600 nM. The EMSA results showed that both catalytically inactive SpCas9 (dCas9) and dCas9ΔCTD22 exhibited similar binding affinities for canonical PAM-containing DNA, with KD values of 19 ± 0.5 nM and 21 ± 0.5 nM, respectively. In contrast, both proteins showed substantially reduced affinity for TTG PAM-containing DNA, with KD values of 200 ± 42 nM for dCas9 and 210 ± 45 nM for dCas9ΔCTD22 (Fig. 1d, 1e, Supplementary Fig. S4, Supplementary Table S1). Thus, Cas9ΔCTD22 exhibited wild-type-like binding affinities toward both the canonical TGG PAM and the noncanonical TTG PAM.

To probe whether Cas9ΔCTD22 might display subtle differences in PAM specificity and cleavage activity, we collectively compared its PAM specificity with SpCas9 using a PAM depletion assay. The results confirmed that Cas9ΔCTD22 retains wild-type-like PAM specificity with no significant changes (Supplementary Fig. S5). Furthermore, comparing DNA cleavage activity over time for each PAM sequence to assess differences in cleavage activity revealed no appreciable differences between SpCas9 and Cas9ΔCTD22 (Supplementary Fig. S6). These results indicate that deletion of residues 1242–1263 does not impair the cleavage activity or PAM specificity of SpCas9, at least under the tested in vitro conditions.

Structural evaluation of the SpCas9 variant deleting residues 1242–1263.

To validate the structural integrity of Cas9ΔCTD22, we determined the structure of dCas9ΔCTD22 in complex with sgRNA and dsDNA. Following a previously reported method6, we reconstituted the ternary complex by incubating purified dCas9ΔCTD22 with sgRNA and dsDNA, which contains a truncated NTS and a TGG PAM sequence with an extended downstream region of PAM. We purified the complex using SEC and confirmed the complex formation by EMSA and native-PAGE (Supplementary Fig. S7). The purified ternary complex was subsequently crystallized, and its structure was determined at 3.6 Å resolution (Supplementary Table S2).

Our structure demonstrates that dCas9ΔCTD22 maintains the overall structural architecture of SpCas9, forming a stable ternary complex with sgRNA and dsDNA, similar to previously reported SpCas9 ternary complex structures (Fig. 2a)6,36,37. Most of the sgRNA-target strand (TS) heteroduplex is well resolved, except for nucleotide U at position + 1 of the sgRNA and two nucleotides, dA(− 20) and dT(− 19), in TS (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Fig. S8). The PAM motif within the NTS is clearly defined and interacts with the conserved R1333 and R1335 of the CTD (Fig. 2c). A GS linker replacing the 1242–1263 region, is visible in the electron density map, although several side chains of serine residues are poorly resolved, likely due to flexibility (Supplementary Fig. S9).

Crystal structure of the dCas9ΔCTD22–sgRNA–dsDNA ternary complex (a) Overall structure of the dCas9ΔCTD22 ternary complex. Individual domains are color-coded, and black box indicates region expanded in panel (c). (b) Schematic representation of the sgRNA, TS, and NTS. Nucleotides shown in bold and underlined are resolved in the crystal structure; those in plain text are not. In the NTS numbering scheme, the first base of the PAM (T base in TGG) is designated as + 1, with downstream bases as + 2 and + 3, and upstream bases as –1, –2, etc. (c) Close-up view of the NTS around the PAM, corresponding to the boxed region in (a). (d) Structural superimposition of the dCas9ΔCTD22 ternary complex with the dCas9 ternary complex (PDB ID: 7Z4I), highlighting the alignment of the REC and HNH domains, as well as RNA–DNA heteroduplex. The dCas9 ternary complex is shown in gray for comparison. (e) Structural comparison of the 1242–1263 region in the dCas9 ternary complex with the corresponding GS linker region (highlighted in yellow) in the dCas9ΔCTD22 ternary complex.

To investigate whether the deletion of residues 1242–1263 compromises the structural integrity of the SpCas9 ternary complex in detail, we compared our dCas9ΔCTD22 structure with previously reported SpCas9 ternary complex structures. Previously reported dCas9 structures have captured the protein in a catalytically inactive, pre-active conformation under artificially induced conditions, such as inactivating mutations at the catalytic site, mismatches between the RNA and target DNA, or absence of Mg2⁺ ions6,8,37. This pre-checkpoint conformation of SpCas9 is well illustrated in the 16-nt matched dCas9 cryo-EM structure (PDB ID: 7Z4I)8. Notably, this state represents a late R-loop propagation intermediate, in which REC2, REC3 and HNH domains have undergone rearrangement, and the hybridization of sgRNA–TS heteroduplex is nearly complete.

Structural alignment of dCas9ΔCTD22 structure with this pre-checkpoint structure (PDB ID: 7Z4I) yields an RMSD of 0.9 Å, indicating high structural similarity across the protein domains, sgRNA, and target DNA (Fig. 2d, Supplementary Fig. S8). Notably, deletion of residues 1242–1263 does not affect the adjacent secondary structures or the overall conformation of the ternary complex (Fig. 2e). These results demonstrate that dCas9ΔCTD22 maintains the canonical architecture of the SpCas9 ternary complex, supporting the structural robustness of this variant despite deletion of a CTD segment.

Integration of evolved E. coli TadA into the 1242–1263 region and evaluation of deaminase activity

Biochemical and structural analyses of Cas9ΔCTD22 identified the 1242–1263 region as dispensable, suggesting that this site could accommodate foreign domains to confer new functionalities, such as base-editing activity. Given that TadA8e is a well-characterized adenine deaminase compatible with single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) substrates, we tested the feasibility of inserting TadA8e into this region of Cas9ΔCTD22. This design aimed to preserve the structural integrity and DNA-targeting capacity of SpCas9 while endowing it with deaminase activity. Previous studies have demonstrated that the insertion site of the deaminase domain within SpCas9 can markedly influence the editing efficiency, editing window, and RNA off-target effects22,38,39,40. Based on this, we hypothesized that inserting the deaminase domain into the CTD of SpCas9 using different linkers could similarly influence both the editing efficiency and the width of the editing window.

To test this, we engineered a series of Cas9-CTD-ABE constructs by replacing residues 1242–1263 of SpCas9 with TadA8e (7–167), incorporating linkers of varying lengths and flexibility: Cas9-CTD-L0-ABE (L0), Cas9-CTD-L3-ABE (L3), Cas9-CTD-L5-ABE (L5), Cas9-CTD-L7-ABE (L7), and Cas9-CTD-Lh-ABE (Lh) (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Table S3). L0 has no linker, whereas L3, L5, and L7 have flexible linkers of G(SG)₃, G(SG)₅, and G(SG)7, respectively. In the case of the Lh variant, the (AEAAAK)₂ASG sequence, which is known to promote α-helix formation41, was used to constrain flexibility of the linker. Editing efficiencies of these constructs were compared with that of the ABE8e, where TadA8e is fused to the N-terminus of nCas919.

Construct design and in vitro functional evaluation of Cas9-CTD-ABE variants. (a) Schematic diagram of the Cas9-ABE constructs used in this study, including Cas9-CTD-ABE variants (replacement of residues 1242–1263 with ABE using different linker configurations), Cas9-ΔHNH-ABE (replacement of residues 792–905 with TadA8e), Cas9-CTD-ins-ABE (insertion of TadA8e between 1246–1249 with deletion of 1247–1248), and Cas9-RuvC-ins-ABE (insertion of TadA8e at residues 1029–1030). Detailed construct information is provided in Supplementary Table S4. (b) DNA sequences used in the deamination assay. Only the NTS sequences are shown. The sgRNA target region is colored in blue; adenines targeted for deamination are shown in red; PAM sequences are highlighted in yellow. (c) Representative TBE-Urea denaturing PAGE images showing deamination cleavage products. (d) Heatmap illustrating A-to-I editing efficiencies across constructs and target positions. Editing efficiency is color-coded according to the scale bar (right), with more intense blue indicating higher editing levels.

In vitro deamination assays were performed using dsDNA substrates containing a single adenine base at various positions on the NTS (Fig. 3b)42. Deamination efficiency was quantified by densitometric analysis of cleaved and uncleaved DNA bands (Fig. 3c, 3d, Table S4). The L0 variant, lacking a linker, showed no detectable deamination activity at any positions (Fig. 3c), indicating that spatial flexibility is essential for TadA8e to access the ssDNA substrate. In contrast, constructs with flexible linkers (L3–L7) exhibited robust activity comparable to ABE8e, but with a modest shift in the editing window toward PAM-proximal positions (Fig. 3d). At positions A3 to A5, ABE8e showed high efficiencies (55% at A3 and 80% or higher at A4 and A5), while the CTD linker variants, L3–L7, exhibited lower activity (< 50% at A3–A5). However, at positions A6–A8, the L3–L7 variants achieved ≥ 75% efficiency, comparable to ABE8e. At A9 and A10, ABE8e exhibited slightly reduced efficiency (~ 60–70%), whereas the L3–L7 variants maintained high efficiency (> 80%). As the editing position moved closer to the PAM (A11–A12), ABE8e efficiency declined sharply, reaching 34% at A11 and 6% at A12. In contrast, the L3–L7 variants retained ~ 80% efficiency at A11 and 30 ~ 45% at A12, followed by a steep drop to ~ 10% at A13.

The rigid linker variant, Lh, exhibited a narrower editing window. It maintained high efficiency (~ 80%) from A6 to A10, but showed a sharp decline to 27% at A11 and minimal activity at A12 position. This suggests that rigid linker, which limits spatial flexibility, may provide a more confined and precise editing window. Increasing linker length from L3 to L7 did not significantly shift or broaden the editing window but slightly enhanced activity at the edges (A4, A5, and A12) (Fig. 3d) .

Furthermore, we compared our Cas9-CTD-ABE constructs with previously reported Cas9-ABE architectures with internal TadA8e insertion. We chose three representative constructs: (i) replacement of the HNH domain with TadA8e (Cas9-ΔHNH-ABE: 792-TadA8e-905)40, (ii) insertion of TadA8e into the CTD (Cas9-CTD-ins-ABE): 1246-linker-TadA8e-linker-1249)22, and (iii) insertion into the RuvC domain (Cas9-RuvC-ins-ABE: 1029-linker-TadA8e-1030)40. In vitro assays showed that Cas9-ΔHNH-ABE exhibited a PAM-proximal editing preference, with maximal efficiency of 94.4% at positions A10 and A11 and sustained high efficiency across A10-A14. The two insertion variants, Cas9-CTD-ins-ABE and Cas9-RuvC-ins-ABE, displayed broader editing windows (Fig. 3c). Notably, Cas9-CTD-ins-ABE maintained > 85% activity from A4 to A11, whereas Cas9-RuvC-ins-ABE showed moderately high efficiencies (> 70%) from A4 to A8 and a discontinuous activity profile with a secondary peak (> 75%) at A10. Although direct comparison with previous studies is complicated by differences in the inserted TadA variant and assay conditions (in vitro vs. in vivo), our results generally showed similar or slightly broader editing windows, along with higher overall activity. For example, Cas9-ΔHNH-ABE exhibited a PAM-proximal bias consistent with prior observations but with higher activity, whereas Cas9-CTD-ins-ABE demonstrated a broader window and enhanced activity in our in vitro assay22,40.

Altogether, these findings suggest that replacing residues 1242–1263 with TadA8e allows for efficient editing, comparable to previously reported Cas9-ABE variants, while offering the ability to fine-tune the editing window through linker design. Thus, our Cas9-CTD-ABE variants represent versatile alternative architectures that complement current strategies and expand the design space for base editors.

Target-specific deamination in E. coli by Cas9-CTD-ABE variants

To evaluate whether the Cas9-CTD-ABE variants we generated could mediate target-specific deamination in vivo, we expressed these variants in a bacterial system and assessed their activity on plasmid DNA (Fig. 4a). Target sequences were designed with a single adenine base at the 6th, 10th, or 13th nucleotide position to probe the editing window and positional specificity of deamination. Successful deamination at these positions would abolish the recognition site for HpyCH4IV restriction enzyme (5ʹ-ACGT-3ʹ), thereby preventing cleavage by HpyCH4IV.

In vivo deamination assays of Cas9-CTD-ABE variants in E. coli. (a) Target DNA sequences (A6, A10, A13) used for in vivo deamination assays. The adenine subjected to deamination is shown in red, and PAM sequences are highlighted in yellow. HpyCH4IV recognition sites (5′-ACGT-3′) are underlined. Successful deamination disrupts the recognition site, preventing enzymatic cleavage. (b) In vivo deamination efficiency assessed using HpyCH4IV digestion of PCR-amplified target regions. Target plasmids were isolated from E. coli expressing the indicated Cas9-CTD-ABE variants (L3, L5, Lh) along with the ABE8e as a control, and PCR products flanking each target site were subjected to restriction digestion. The negative ( −) and positive ( +) controls used the NTS and the A13 target plasmids, respectively, without Cas9-CTD-ABE expression for comparison.

Through restriction enzyme cleavage analysis combined with sequencing of the target region, we observed that all tested variants, including ABE8e as a control, specifically deaminated adenine residues at positions 6 and 10 (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Fig. S10). The observed deamination efficiencies at each target site closely paralleled the in vitro results, showing high efficiency at position 10 and negligible deamination at position 13 for our Cas9-CTD-ABE variants, whereas ABE8e exhibited higher efficiency at position A6. We also evaluated previously reported Cas9-ABE constructs, used in prior in vitro assays, under the same in vivo conditions. Overall, the results were consistent with the in vitro findings: Cas9-ΔHNH-ABE exhibited a PAM-proximal bias, and Cas9-CTD-ins-ABE showed a broader editing window. The only exception was Cas9-RuvC-ins-ABE, which exhibited substantial in vivo activity at position A13 despite showing only minimal activity (~ 5%) in vitro (Supplementary Fig. S11).

Thus, these results confirm that the Cas9-CTD-ABE variants retain their target-specific deamination activity in vivo, highlighting their potential as tools for intracellular targeted base editing.

Discussion

Engineering proteins with foreign domains requires identifying insertion sites that tolerate structural perturbation while preserving function. For SpCas9, this is particularly challenging due to its multi-domain architecture and the essential roles of domains like REC1, REC2, and HNH in RNA-guided DNA targeting and cleavage. In this study, we focused on the CTD, which exhibits low sequence conservation across Cas9 orthologs and has not been thoroughly explored for domain replacement. REC1 and REC2 also exhibited less than 5% sequence conservation among the ten Cas9 orthologs analyzed, suggesting that further exploration may reveal a more tolerant loop or segment within these domains for domain replacement—although their critical roles in sgRNA-DNA binding and DNA unwinding present significant engineering challenges7,23,24,43.

Through biochemical and structural studies, we identified residues 1242–1263 in the CTD as dispensable for SpCas9 activity. This region includes residue 1249, which was previously implicated as an insertion hotspot in circular permutation studies44. In this study, we demonstrated through structural determination of the ternary complex that deletion of this region does not alter the overall architecture of SpCas9. Additionally, we showed that deleting this segment did not disrupt cleavage activity and PAM recognition, highlighting it as a structurally tolerant region capable of accommodating foreign domains. Notably, large-scale MISER mutational scanning of SpCas9, which systematically mapped the deletion landscape, did not highlight this segment as functionally relevant, underscoring the value of our structural and sequence-guided analysis in identifying an overlooked but permissive site45.

As a proof of concept, we designed SpCas9 variants with adenine deaminase functionality by inserting the well-characterized TadA8e domain into the 1242–1263 region with different linker configurations. These constructs retained high base editing efficiency, particularly at positions A6–A11, and exhibited editing windows comparable to or narrower than ABE8e, the N-terminal fusion variant. Linker composition significantly influenced editing profiles: flexible linkers (L3–L7) enabled robust activity with modest PAM-proximal shifts in the editing window, while the rigid helical linker (Lh) narrowed the editing range, offering greater positional precision. We initially aimed to rationalize the correlation between linker length and shifts in the editing window. To this end, we measured the distance between the N- and C-termini of TadA8e in the ABE8e cryo-EM structure (PDB ID: 6VPC), which is approximately 26 Å (Ser7-Lys160), and compared it with the distance between residues 1242 and 1263 in SpCas9, which is about 18 Å (Supplementary Fig. S12). Thus, incorporation of TadA8e residues Ser7-Asn167 into our constructs appears structurally feasible, but additional linker is likely required for TadA8e to reach a catalytically competent position, consistent with our assay data showing that the L0 variant exhibited no detectable deamination activity. However, precise rationalization remains difficult because structural information on Cas9-CTD-ABE in complex with sgRNA-dsDNA is currently lacking. Without such information, it is challenging to predict the exact position of TadA8e required for activity and, consequently, the optimal linker length for tuning the editing window. Future structural studies capturing TadA8e bound to DNA are expected to enable more rational linker design.

We further demonstrated that the Cas9-CTD-ABE variants exhibit target-specific deamination in vivo using an E. coli plasmid assay, with efficiencies consistent with in vitro results. Although our study focused primarily on structural and biochemical characterization and therefore relied on an E. coli system for in vivo validation, additional experiments in mammalian cells will be necessary to fully establish their activity and utility in more physiologically relevant contexts. Nevertheless, since our constructs showed comparable activity to previously reported ABE constructs when tested side by side in E. coli, and those ABEs have previously been demonstrated to function in mammalian cells, our constructs are also likely to exhibit similar activity in mammalian systems. Therefore, these findings suggest that the 1242–1263 region may be a robust and modular insertion site for engineering compact and functionally diverse Cas9 variants. Beyond Cas9, recent efforts in genome editor engineering, such as the evolution-guided design of IscB for epigenome editing in vivo49, have underscored the potential of domain modularity and evolutionary adaptability in engineering genome-editing tools.

In addition to adenine base editing, this newly validated domain replacement site may provide a versatile platform for expanding SpCas9 capabilities in multiple directions. For instance, insertion of allosteric regulatory modules such as ER-LBD50,51, could enable external control of SpCas9 activity in response to ligands or cellular signals. A similar approach was previously attempted by inserting ER-LBD into the REC2 domain, but the resulting SpCas9 variant retained only about half of the wild-type indel efficiency21. The 1242–1263 site may provide improved performance due to its structural tolerance. Similarly, the incorporation of sensor or reporter modules could support real-time activity monitoring or logic-gated control in synthetic biology applications. Another approach is to fuse single-stranded DNA nucleases at this site, to enable programmable sticky-end generation for cloning or biasing repair outcomes toward homology-directed repair over non-homologous end joining, potentially offering more precise genome editing52. However, identifying a suitably compact yet efficient ssDNA nuclease remains a challenge.

In conclusion, our findings demonstrate that replacement of the internal region spanning residues 1242–1263 with a foreign domain with an appropriate linker can be achieved without significantly compromising structural integrity. In this study, we validated the dispensability of the 1242–1263 region by structural determination of the dCas9ΔCTD22-sgRNA-dsDNA ternary complex. This result not only broadens the scope of SpCas9 engineering but also provides a foundation for the development of next-generation gene editors with customized functionalities for diverse biomedical and synthetic biology applications.

Methods

Cloning

The pMJ806 vector obtained from Addgene (Addgene #39312) was modified and subsequently cloned to generate the constructs4. The E. coli codon-optimized TadA8e DNA was synthesized by LugenSci (Korea). To generate constructs incorporating TadA8e into the residues 1242–1263 region, the modified pMJ806 vector was amplified by PCR using Q5 High-Fidelity DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs, NEB) to serve as the backbone. The TadA8e insert was also amplified by PCR, and then the amplified backbone and insert were assembled using the HiFi DNA Assembly Master Mix (NEB). In the same manner, additional constructs—Cas9-ΔHNH-ABE, Cas9-CTD-ins-ABE, and Cas9-RuvC-ins-ABE—were generated using PCR amplification of the corresponding junction fragments followed by HiFi DNA Assembly (NEB).

Sequence analysis of C-terminal domain of Cas9 homologs

The 3D structures of selected Cas9 homologs, available in the RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB), were retrieved, and their sequence information was obtained from UniProt. For analysis, the sequences corresponding to the CTD, wedge domain, and PI domain were extracted and aligned using T-Coffee53. The alignment was then visualized with ESPript 3.054.

DNA preparation

All DNA sequences used in this study are listed in Table S4. DNA for cleavage assays and EMSA was synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT) and labeled with a Cy5 fluorophore at the 5ʹ end of the target strand, followed by HPLC purification. DNA used for structural determination was also synthesized by IDT, and these oligonucleotides were annealed by heating to 95 °C for 5 min and gradually cooled to room temperature.

DNA for the deamination assay was prepared as previously reported with some modification18. A 14-mer primer labeled with Cy5 at the 5ʹ end, which served as the non-target strand, was ordered from IDT, and the 50-nt target strand was synthesized and HPLC-purified by Cosmogenetech (Korea). For annealing and primer extension, the strands were mixed in a solution containing NEBuffer2 (NEB) and 250 μM dNTPs with each strand at a final concentration of 4 μM in a total volume of 50 μl. The mixture was heated to 95 °C for 5 min and then slowly cooled to 45 °C at a rate of 0.1 °C/s. After cooling, 5 units of Klenow fragment (exo–) (NEB) were added, and the reaction was incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. The reaction mixture was then separated on a 6% native polyacrylamide gel (0.5 × TBE). The band containing the desired product was excised and DNA was extracted using the previously described crush-and-soak method55. Finally, the extracted DNA was further purified using a DNA clean-up kit (NEB).

In vitro sgRNA transcription using T7 RNA polymerase

The dsDNA template for in vitro sgRNA transcription was PCR-amplified using Q5 High-Fidelity DNA polymerase with the primers (Supplementary Table S5). For the transcription of sgRNA used in cleavage assay, EMSA and structure determination (Supplementary Table S6), the DNA template was pooled and purified by phenol–chloroform extraction. Following purification, the transcription reaction was performed by mixing the components as previously described56. Specifically, T7 RNA polymerase was expressed and purified according to protocol provided by Addgene (Addgene plasmid #174866).

The reaction was quenched by adding DNase I (NEB) and heat-inactivated by incubation at 95 °C for 5 min. Subsequently, the mixture containing the transcribed sgRNA was applied to a Resource Q 6 ml column (GE Healthcare) and further purified using a Superdex 200 10/300 GL gel-filtration column (GE Healthcare) with sgRNA buffer consisting of 20 mM Tris (pH 8.0) and 100 mM NaCl. The gel-filtration fractions were analyzed using 12% acrylamide TBE-Urea denaturing polyacrylamide gel. Fractions containing sgRNA were concentrated to 100 μM, flash-frozen using liquid nitrogen, and stored at − 80 °C.

For the preparation of sgRNA for the deamination assay, the PCR products for the sgRNA template were purified using the DNA Cleanup Kit (NEB). The sgRNAs were then synthesized using the HiScribe T7 High Yield RNA Synthesis Kit (NEB) and subsequently purified using the Monarch RNA Cleanup Kit (NEB) following the manufacturer’s protocol.

Cas9 and Cas9ΔCTD22 protein expression and purification

Purification of (d)Cas9 and (d)Cas9ΔCTD22 constructs was based on previously described procedures with some modifications4. Modified pMJ806 plasmid encoding His6-MBP-TEV-(d)Cas9 and its derivative constructs were transformed into E. coli Rosetta (DE3) competent cells. Cells containing plasmids were grown in Terrific Broth until OD600 reached 0.6–0.8. Protein expression was induced by adding 0.1 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and incubated at 20 °C for 16–18 h.

After induction, cells were harvested and resuspended in a lysis buffer composed of 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 500 mM NaCl, and 5 mM imidazole. Cell lysis was performed using a C-3 Emulsiflex (Avestin). The lysate was centrifuged, and the supernatant was loaded onto a Ni–NTA resin (Qiagen) pre-equilibrated with the lysis buffer. After 1 h of incubation, the column was washed with a buffer containing 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 500 mM NaCl, and 20 mM imidazole. The protein was then eluted using an elution buffer composed of 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 250 mM NaCl, and 200 mM imidazole. TEV protease was then added, and the eluent was incubated overnight at 4 °C for proteolytic cleavage. On the following day, further purification was performed using a HiTrap SP HP 5 ml column (GE Healthcare), with a NaCl gradient from 250 mM to 1 M in 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.5). Fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and pooled. The pooled fractions were then subjected to size-exclusion chromatography on a Superdex 200 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare), equilibrated with a buffer containing 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.5) and 300 mM NaCl. The protein-containing fractions were concentrated to the desired level, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored in aliquots at − 80 °C.

Expression and purification of ABE8e and Cas9-ABE variants

Expression vectors encoding ABE8e and Cas9-ABE variants (Cas9-CTD-ABE constructs, Cas9-ΔHNH-ABE, Cas9-CTD-ins-ABE, Cas9-RuvC-ins-ABE), each bearing an N-terminal His6-MBP tag removable by TEV protease, were transformed into E. coli Rosetta (DE3) competent cells. A single colony was picked and inoculated into LB medium supplemented with 1% (w/v) glucose. The culture was grown at 30 °C until the OD600 reached 1.0. The culture was cooled to 4 °C, and protein expression was induced by adding 0.1 mM IPTG. The induction was carried out overnight at 16 °C.

After induction, cells were harvested and resuspended in lysis buffer containing 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 1 M NaCl, 10% glycerol, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol (BME), and 5 mM imidazole. Cell lysis was performed by sonication, and the lysate was centrifuged to remove cell debris. The supernatant was incubated with Ni–NTA resin (Qiagen) pre-equilibrated with the lysis buffer for 1 h. The resin was then washed with 10 column volumes (CV) of wash buffer containing 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 1 M NaCl, 10% glycerol, 5 mM BME, 20 mM imidazole, and 0.025% (v/v) Tween-20. The protein was eluted with an elution buffer consisting of 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 400 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 5 mM BME, and 200 mM imidazole. TEV protease was added to the eluted protein, and the mixture was incubated overnight for proteolytic cleavage. On the following day, the protein solution was loaded onto a HiTrap Heparin HP 5 ml (GE Healthcare) column and purified using a NaCl gradient ranging from 400 mM to 1 M. The final purification step involved size-exclusion chromatography using on a Superose6 Increase 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with a buffer composed of 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 400 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, and 0.1 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP). The protein-containing fractions were concentrated to the desired concentration, aliquoted, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at − 80 °C.

DNA oligonucleotide cleavage assay

Cas9 and sgRNA were mixed in reaction buffer A, consisting of 20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 10% (v/v) glycerol and 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), at final concentrations of 1 μM each and incubated at room temperature for 10 min. The reaction was initiated by adding Cy5-labeled dsDNA to the mixture to 10 nM final concentration at 37 °C. At each time point, 9 μl samples were withdrawn and quenched by adding 1 μl of 0.5 M EDTA (pH 8.0). Each quenched sample was then treated with 20 μg of RNase A (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and incubated at room temperature for 20 min, followed by the addition of 20 μg of proteinase K (Invitrogen) and further incubation at 37 °C for 30 min. The samples were analyzed using TBE-Urea denaturing polyacrylamide gel and visualized using ChemiDoc MP imaging system (Bio-Rad).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay

The binding affinity differences between dCas9 and dCas9ΔCTD22 toward DNA were measured using EMSA. dCas9 (or dCas9ΔCTD22) and sgRNA were incubated in reaction buffer A supplemented with 0.01% (v/v) Triton X-100, at final concentrations ranging from 2.5 nM to 800 nM, and incubated at room temperature for 10 min. Cy5-labeled dsDNA was then added to a final concentration of 10 nM, and the reaction was incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. Following the reaction, the samples were loaded onto a 6% native polyacrylamide gel (0.5 × TBE) and electrophoresed at 135 V for 1 h at 4 °C. Visualization and quantification of the bound fraction were performed using the ChemiDoc MP imaging system. The dissociation constant (KD) values were calculated using the bound fraction data with GraphPad Prism 8.4.3 using a cooperative binding model.

PAM depletion assays

For the PAM depletion assay, a pUC19-based plasmid library with five randomized nucleotides (bold) upstream of the target sequence (underlined) was constructed by inserting the following sequence between the SalI and EcoRI sites: 5’-GTCGACTAATAAAAGGGCGATCTAATGAANNNNNTCGAATTC-3’, where (N) represents randomized nucleotides and a target sequence is underlined. PAM depletion assays were performed with purified SpCas9 and Cas9ΔCTD22, respectively. To prepare the reaction, combine 200 nM Cas9 and 100 nM sgRNA, along with 1 mM TCEP, 1 × NEB Cutsmart buffer (comprising 50 mM Potassium Acetate, 20 mM Tris–acetate, 10 mM Magnesium Acetate, and 100 µg/mL BSA, pH 7.9, at 25 °C), and nuclease-free water to a total volume of 10 µL. After a 10 min-incubation for the formation of Cas9-sgRNA complex at 25 °C, library DNAs were added and incubated at 37 °C for various time points. The reactions were quenched by adding 0.5 µL of 0.5 M EDTA (pH 8.0) and 1 µL of 800 Units/mL Proteinase K (NEB). The samples were then frozen in liquid nitrogen until their use. For PCR amplification, the sample DNAs were cleaned and isolated. 2 ng of eluted DNA is PCR-amplified using 1 × Taq DNA Polymerase buffer, 1.6 mM MgCl₂, 0.8 mM dNTPs, 520 nM primer mix, 0.3 µL of Taq DNA polymerase (Bioneer), and nuclease-free water to a final volume of 50 µL per reaction. Each reaction time point sample is amplified with different primer sets (Supplementary Table S7) to distinguish the time points. The library DNA fragments from 160-bp to 200-bp depending on the primer sets used for PCR were generated. From PCR, Only the uncleaved DNAs were amplified and retrieved. Next generation sequencing (NGS) was performed through a service provided by Macrogen Inc. The amplicons were ligated to adapters, and the NGS library is synthesized using the TruSeq Nano DNA Kit, essentially followed by the manufacturer’s protocol. The sequencer used is an Illumina system. The reads were merged and sorted based on the intended primer sets to determine whether the correct inserted sequences are present.

dCas9ΔCTD22 ternary complex reconstitution and purification

dCas9ΔCTD22 and sgRNA were mixed at a molar ratio of 1:1.25 in reaction buffer A and incubated at room temperature for 10 min. Subsequently, dsDNA containing a TGG PAM and a truncated NTS was added at a 1.5 molar ratio relative to the protein, and the reaction was incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. The final concentrations of dCas9ΔCTD22, sgRNA, and dsDNA were 5 μM, 6.25 μM, and 7.5 μM, respectively. The reaction mixture was then loaded onto a HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 200 pg column (GE Healthcare) pre-equilibrated with 20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT to separate the complex from excess sgRNA and dsDNA. Complex reconstitution and separation were confirmed by analyzing fractions on a 6% native polyacrylamide gel (0.5 × TBE). After electrophoresis, gels were stained with SYBR Gold (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and visualized using ChemiDoc MP imaging system.

Crystallization and structure determination

Fractions containing the complex were pooled and concentrated to an A260 value of approximately 23. Crystallization screening and optimization were performed, initially yielding crystals in a solution containing 0.1 M HEPES (pH 7.5), 0.2 M potassium acetate, and 20% (v/v) PEG 3350. These crystals were used for seeding to obtain diffraction-quality crystals in a solution containing 0.07 M HEPES (pH 7.5), 0.18 M potassium acetate, and 14% (v/v) PEG 3350. Crystals were harvested using a cryo-protectant solution of 0.1 M HEPES (pH 7.5), 0.2 M potassium acetate, 20% (v/v) PEG 3350, and 20% (v/v) glycerol, and cryo-cooled in liquid nitrogen. X-ray diffraction data were collected at the 5C beamline of the Pohang Accelerator Laboratory with an oscillation of 0.2° per frame, resulting in 600 frames covering 120°. The collected data were processed, and phasing was carried out using molecular replacement (MR) with a modified model based on Cas9-sgRNA-dsDNA R-loop structure (PDB ID: 5F9R), using the Phaser-MR in PHENIX suite57. The resulting model was manually rebuilt using Coot58 and refined with phenix.refine. The processed model displayed a Ramachandran favored region of 95.38% and an allowed region of 4.62%. The data collection and refinement statistics are summarized in Table S2.

In vitro deamination assay

To evaluate the activity and editing window of the newly designed ABEs, an in vitro deamination assay was performed following previously published methods with minor modification42. ABE and sgRNA were mixed to a final concentration of 500 nM each and incubated at room temperature for 10 min in deamination buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 100 mM KCl, 5 mM MgSO4, 1 mM DTT, and 5% (v/v) glycerol). Cy5-labeled dsDNA, designed for the deamination assay, was then added, and the reaction was incubated at 37 °C for 1 h.

The reaction was quenched by adding 20 μg of proteinase K and incubation at 37 °C for 30 min. Proteinase K was inactivated by heating at 95 °C for 10 min. Subsequently, NEBuffer 4 and 1 unit of endonuclease V (NEB) were added to each sample, and the mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. Samples were then mixed with TBE-Urea denaturing sampling buffer (1 × TBE, 3.5 M urea, 0.05% (w/v) bromophenol blue, and 5% Ficoll) and heated at 95 °C for 5 min to inactivate the enzymes and denature the DNA.

The samples were loaded onto a 12% TBE-Urea denaturing polyacrylamide gel and subjected to electrophoresis at 200 V for 40 min. Cleaved fractions were visualized and quantified using the ChemiDoc MP system, and data analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism.

Cloning for the In vivo bacterial deamination assay

Details of the primers used for cloning are provided in Table S5. For bacterial expression of dCas9-CTD-ABE variants, pSU-araC-Cas9 (Addgene #120423) was used as the backbone. A single KpnI and XhoI site was introduced by PCR amplification with Primer Set 1, and a D10A mutation was generated by site-directed mutagenesis using Primer Set 2. The C-terminal portion of the Cas9 gene in pSU-araC-Cas9 was then replaced with KpnI–XhoI fragments carrying the dCas9-CTD-ABE inserts.

To prepare target plasmids for in vivo deamination, pH3U3-mcs (Addgene #12609) was modified by removing the lac promoter and His3 gene. Subsequently, a new promoter (Primer Set 3) was inserted using BamHI and EcoRI. The A6, A10, and A13 target sequences (Primer Sets 4–6) were then introduced at the EcoRI and SalI sites.

For sgRNA expression, a vector was constructed by inverse PCR of pTargetF (Addgene #62226) using Primer Sets 7–9, each containing the A6, A10, or A13 target sequences, respectively. The resulting constructs were employed for the bacterial deamination assays.

Bacterial deamination assay in E. coli

In vivo deamination experiments were performed using the US0hisB−pyrF− strain (Addgene #12614), which is derived from XL1-blue and carries an F’ episome as well as the lacIq repressor. This strain also lacks hisB and pyrF, which are the bacterial counterparts of His3 and Ura3, respectively.

For the deamination assay, E. coli cells were transformed with three plasmids: one expressing a Cas9-ABE variant (including dCas9-CTD-ABE and other engineered dCas9-ABE constructs), one expressing the sgRNA, and one containing the target DNA site. Cultures were grown in LB medium supplemented with 30 μg/mL kanamycin, 50 μg/mL spectinomycin, and 30 μg/mL chloramphenicol. Expression of dCas9-ABE variant was induced by adding 10 mM arabinose, and the cultures were incubated overnight at 37 °C. The following day, cells were plated on LB agar containing the same antibiotic concentrations and arabinose, then incubated overnight at 37 °C. Colonies were harvested, and isolated plasmid DNA served as the template in a PCR reaction to assess deaminase activity. Sanger sequencing was also performed on the isolated DNA to verify the presence or absence of an A → G substitution at the target position.

To verify deamination, a 412-bp fragment encompassing the target sequence was amplified using the TadA8e-PCR primer set. The resulting PCR product was then subjected to HpyCH4IV restriction digestion, which targets the 5ʹ-ACGT-3ʹ sequence. In cases where the target adenine was deaminated (A → G), cleavage by HpyCH4IV was prevented. If no base modification occurred, the DNA substrate remained susceptible to HpyCH4IV digestion.

Data availability

The structural data supporting this study have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) with the accession code 9KJ6.

References

-

Cong, L. et al. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science 339, 819–823. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1231143 (2013).

-

Jiang, W., Bikard, D., Cox, D., Zhang, F. & Marraffini, L. A. RNA-guided editing of bacterial genomes using CRISPR-Cas systems. Nat. Biotechnol. 31, 233–239. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.2508 (2013).

-

Shan, Q. et al. Targeted genome modification of crop plants using a CRISPR-Cas system. Nat. Biotechnol. 31, 686–688. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.2650 (2013).

-

Jinek, M. et al. A programmable dual-RNA–guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science 337, 816–821. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1225829 (2012).

-

Sternberg, S. H., Redding, S., Jinek, M., Greene, E. C. & Doudna, J. A. DNA interrogation by the CRISPR RNA-guided endonuclease Cas9. Nature 507, 62–67. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13011 (2014).

-

Anders, C., Niewoehner, O., Duerst, A. & Jinek, M. Structural basis of PAM-dependent target DNA recognition by the Cas9 endonuclease. Nature 513, 569–573. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13579 (2014).

-

Cofsky, J. C., Soczek, K. M., Knott, G. J., Nogales, E. & Doudna, J. A. CRISPR–Cas9 bends and twists DNA to read its sequence. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 29, 395–402. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41594-022-00756-0 (2022).

-

Pacesa, M. et al. R-loop formation and conformational activation mechanisms of Cas9. Nature 609, 191–196. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-05114-0 (2022).

-

Doudna, J. A. & Charpentier, E. The new frontier of genome engineering with CRISPR-Cas9. Science 346, 1258096. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1258096 (2014).

-

Wang, J. Y. & Doudna, J. A. CRISPR technology: A decade of genome editing is only the beginning. Science 379, eadd8643. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.add8643 (2023).

-

Ribeiro, L. F., Ribeiro, L. F. C., Barreto, M. Q. & Ward, R. J. Protein engineering strategies to expand CRISPR-Cas9 applications. Int. J. Genom. 2018, 1652567. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/1652567 (2018).

-

Huang, X., Yang, D., Zhang, J., Xu, J. & Chen, Y. E. Recent advances in improving gene-editing specificity through CRISPR-Cas9 nuclease engineering. Cells 11, 2186 (2022).

-

Kovalev, M. A., Davletshin, A. I. & Karpov, D. S. Engineering Cas9: next generation of genomic editors. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 108, 209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-024-13056-y (2024).

-

Dominguez, A. A., Lim, W. A. & Qi, L. S. Beyond editing: repurposing CRISPR–Cas9 for precision genome regulation and interrogation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 17, 5–15. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrm.2015.2 (2016).

-

Chen, B. et al. Dynamic imaging of genomic loci in living human cells by an optimized CRISPR/Cas system. Cell 155, 1479–1491. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.001 (2013).

-

Konermann, S. et al. Genome-scale transcriptional activation by an engineered CRISPR-Cas9 complex. Nature 517, 583–588. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14136 (2015).

-

Gaudelli, N. M. et al. Programmable base editing of A•T to G•C in genomic DNA without DNA cleavage. Nature 551, 464–471. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature24644 (2017).

-

Komor, A. C., Kim, Y. B., Packer, M. S., Zuris, J. A. & Liu, D. R. Programmable editing of a target base in genomic DNA without double-stranded DNA cleavage. Nature 533, 420–424. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature17946 (2016).

-

Richter, M. F. et al. Phage-assisted evolution of an adenine base editor with improved Cas domain compatibility and activity. Nat. Biotechnol. 38, 883–891. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-020-0453-z (2020).

-

Mout, R., Ray, M., Lee, Y.-W., Scaletti, F. & Rotello, V. M. In Vivo Delivery of CRISPR/Cas9 for therapeutic gene editing: progress and challenges. Bioconjug. Chem. 28, 880–884. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.7b00057 (2017).

-

Oakes, B. L. et al. Profiling of engineering hotspots identifies an allosteric CRISPR-Cas9 switch. Nat. Biotechnol. 34, 646–651. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.3528 (2016).

-

Villiger, L. et al. Replacing the SpCas9 HNH domain by deaminases generates compact base editors with an alternative targeting scope. Mol. Ther. – Nucleic Acids 26, 502–510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omtn.2021.08.025 (2021).

-

Nishimasu, H. et al. Crystal structure of Cas9 in complex with guide RNA and target DNA. Cell 156, 935–949. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.001 (2014).

-

Palermo, G. et al. Key role of the REC lobe during CRISPR–Cas9 activation by ‘sensing’, ‘regulating’, and ‘locking’ the catalytic HNH domain. Q. Rev. Biophys. 51, e9. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033583518000070 (2018).

-

Hirano, H. et al. Structure and engineering of francisella novicida Cas9. Cell 164, 950–961. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2016.01.039 (2016).

-

Yamada, M. et al. Crystal structure of the minimal cas9 from campylobacter jejuni reveals the molecular diversity in the CRISPR-Cas9 systems. Mol. Cell 65, 1109-1121.e1103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2017.02.007 (2017).

-

Hirano, S. et al. Structural basis for the promiscuous PAM recognition by corynebacterium diphtheriae Cas9. Nat. Commun. 10, 1968. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-09741-6 (2019).

-

Sun, W. et al. Structures of Neisseria meningitidis Cas9 complexes in catalytically poised and anti-CRISPR-inhibited states. Mol. Cell 76, 938-952.e935. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2019.09.025 (2019).

-

Zhang, Y. et al. Catalytic-state structure and engineering of Streptococcus thermophilus Cas9. Nat. Catal. 3, 813–823. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41929-020-00506-9 (2020).

-

Das, A. et al. Coupled catalytic states and the role of metal coordination in Cas9. Nat. Catal. 6, 969–977. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41929-023-01031-1 (2023).

-

Du, W. et al. Full-length model of SaCas9-sgRNA-DNA complex in cleavage state. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 1204. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24021204 (2023).

-

Eggers, A. R. et al. Rapid DNA unwinding accelerates genome editing by engineered CRISPR-Cas9. Cell 187, 3249-3261.e3214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2024.04.031 (2024).

-

Tang, N. et al. Molecular basis and genome editing applications of a compact eubacterium ventriosum CRISPR-cas9 system. ACS Synth. Biol. 13, 269–281. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssynbio.3c00501 (2024).

-

Nishimasu, H. et al. Crystal Structure of staphylococcus aureus Cas9. Cell 162, 1113–1126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.007 (2015).

-

Edraki, A. et al. A compact, high-accuracy Cas9 with a dinucleotide PAM for in vivo genome editing. Mol. Cell https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2018.12.003 (2019).

-

Jiang, F. et al. Structures of a CRISPR-Cas9 R-loop complex primed for DNA cleavage. Science 351, 867–871. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aad8282 (2016).

-

Zhu, X. et al. Cryo-EM structures reveal coordinated domain motions that govern DNA cleavage by Cas9. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 26, 679–685. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41594-019-0258-2 (2019).

-

Li, S. et al. Docking sites inside Cas9 for adenine base editing diversification and RNA off-target elimination. Nat. Commun. 11, 5827. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-19730-9 (2020).

-

Liu, Y. et al. A Cas-embedding strategy for minimizing off-target effects of DNA base editors. Nat. Commun. 11, 6073. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-19690-0 (2020).

-

Chu, S. H. et al. Rationally designed base editors for precise editing of the sickle cell disease mutation. The CRISPR Journal 4, 169–177. https://doi.org/10.1089/crispr.2020.0144 (2021).

-

Arai, R., Ueda, H., Kitayama, A., Kamiya, N. & Nagamune, T. Design of the linkers which effectively separate domains of a bifunctional fusion protein. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 14, 529–532. https://doi.org/10.1093/protein/14.8.529 (2001).

-

Lapinaite, A. et al. DNA capture by a CRISPR-Cas9-guided adenine base editor. Science 369, 566–571. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abb1390 (2020).

-

Sung, K., Park, J., Kim, Y., Lee, N. K. & Kim, S. K. Target specificity of Cas9 nuclease via DNA rearrangement regulated by the REC2 domain. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 7778–7781. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.8b03102 (2018).

-

Huang, T. P. et al. Circularly permuted and PAM-modified Cas9 variants broaden the targeting scope of base editors. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 626–631. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-019-0134-y (2019).

-

Shams, A. et al. Comprehensive deletion landscape of CRISPR-Cas9 identifies minimal RNA-guided DNA-binding modules. Nat. Commun. 12, 5664. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-25992-8 (2021).

-

Lee, H. et al. A high-throughput single-molecule platform to study DNA supercoiling effect on protein–DNA interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkaf581 (2025).

-

von Hippel, P. H., Johnson, N. P. & Marcus, A. H. Fifty years of DNA “Breathing”: Reflections on old and new approaches. Biopolymers 99, 923–954. https://doi.org/10.1002/bip.22347 (2013).

-

Merrikh, H., Zhang, Y., Grossman, A. D. & Wang, J. D. Replication–transcription conflicts in bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 10, 449–458. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro2800 (2012).

-

Kannan, S. et al. Evolution-guided protein design of IscB for persistent epigenome editing in vivo. Nat. Biotechnol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-025-02655-3 (2025).

-

Shiau, A. K. et al. The structural basis of estrogen receptor/coactivator recognition and the antagonism of this interaction by tamoxifen. Cell 95, 927–937. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81717-1 (1998).

-

Tanenbaum, D. M., Wang, Y., Williams, S. P. & Sigler, P. B. Crystallographic comparison of the estrogen and progesterone receptor’s ligand binding domains. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 95, 5998–6003. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.95.11.5998 (1998).

-

Chauhan, V. P., Sharp, P. A. & Langer, R. Altered DNA repair pathway engagement by engineered CRISPR-Cas9 nucleases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 120, e2300605120. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2300605120 (2023).

-

Notredame, C., Higgins, D. G. & Heringa, J. T-coffee: a novel method for fast and accurate multiple sequence alignment11Edited by J. Thornton. J. Molecular Biol. 302(205), 217. https://doi.org/10.1006/jmbi.2000.4042 (2000).

-

Robert, X. & Gouet, P. Deciphering key features in protein structures with the new ENDscript server. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, W320–W324. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gku316 (2014).

-

Green, M. R. & Sambrook, J. Isolation of DNA fragments from polyacrylamide gels by the crush and soak method. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. https://doi.org/10.1101/pdb.prot100479 (2019).

-

Anders, C. & Jinek, M. Methods in Enzymology (Academic Press, 2014).

-

Adams, P. D. et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta. Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 213–221. https://doi.org/10.1107/S0907444909052925 (2010).

-

Emsley, P., Lohkamp, B., Scott, W. G. & Cowtan, K. Features and development of coot. Acta. Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 486–501. https://doi.org/10.1107/S0907444910007493 (2010).

Acknowledgements

We thank the beamline 5C staff at Pohang Accelerator Laboratory (PAL, Korea) for help with X-ray diffraction data collection.

Funding

Samsung Science and Technology Foundation, SRFC-MA1801-09 (to Y-GK) and National Research Foundation of Korea grant, RS-2024-00440289 (to H-JC).

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, S., Won, H., Bae, J. et al. Structural and functional insights into internal domain replacement in SpCas9 for protein engineering. Sci Rep 15, 41528 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25367-9

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

Version of record:

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25367-9