- Research

- Open access

- Published:

- Marta Barros-Reguera1,

- Esteban Lopez-Tavera1,

- Gabriela C. Schröder1,

- Greta Nardini1,

- Kenneth A. Kristoffersen1,

- Iván Ayuso-Fernández1,2,

- Vincent G. H. Eijsink1 &

- …

- Morten Sørlie1

Biotechnology for Biofuels and Bioproducts volume 18, Article number: 83 (2025) Cite this article

Abstract

Unspecific peroxygenases (UPOs) are versatile enzymes capable of oxidizing a broad range of substrates, using hydrogen peroxide as the sole co-substrate. In this study, UPOs were evaluated for their potential in the selective oxyfunctionalization of the phenolic lignin monomer 4-propylguaiacol (4-PG) to generate versatile scaffolds for the synthesis of high-value compounds. In addition to the desired peroxygenase reaction, the phenolic group of 4-PG is susceptible to undesirable one-electron oxidation (peroxidase activity). Assessment of the activity of 19 UPOs from phylogenetically diverse clades toward 4-PG revealed that several UPOs could serve as potential biocatalysts for the functionalization of 4-PG, with some enzymes showing both promising conversion yields (>50%) and regioselectivity for the peroxygenase reaction. Pronounced differences in peroxygenase:peroxidase activity ratios and regioselectivity were observed. Comparative analysis—supported by experimental activity profiles and structural data—suggest that a more constrained active-site topology contributes to the peroxygenase activity. UPOs from a clade within the Ascomycota phylum with high peroxygenase activity possess a unique aliphatic pocket in their catalytic centers. Our study provides valuable insights into the structure–function relationships underpinning enhanced peroxygenase activity of UPOs and provides a functional mapping of a broad UPO-sequence space for 4-PG, highlighting these enzymes as promising catalysts for the selective oxyfunctionalization of a phenolic lignin monomer.

Background

Phenolic compounds hold significant industrial interest due to their unique chemical properties and broad applications, such as use in pharmaceuticals (e.g., aspirin) and as antioxidants in food [1,2,3,4]. Currently, approximately 95% of phenolics are produced via the cumene oxidation process, which relies on petroleum-derived raw materials [5]. This dependence on petrochemical feedstocks raises considerable sustainability concerns, as these processes depend on non-renewable fossil resources and contribute to a substantial environmental footprint.

Inedible plant biomass, also referred to as lignocellulosic biomass, presents a promising renewable, CO2-neutral, and widely available alternative [6]. Lignin, which constitutes about one-third of lignocellulosic biomass, contains a high content of phenolic groups. Among the various strategies for lignin extraction and valorization, reductive catalytic fractionation (RCF) has emerged as an effective method for depolymerizing lignin into phenolic monomers [6,7,8]. Recent advancements in separation technologies, such as counter-current chromatography (CCC), have significantly improved the isolation and purification of lignin-derived monomers and oligomers [9]. Among the lignin-derived monomers obtained through these processes, 4-propylguaiacol (4-PG) has been identified as a major product [7,8,9].

Tailored oxyfunctionalization of lignin-derived monomers, such as 4-PG, holds the potential to greatly expand their applications by serving as versatile scaffolds for the synthesis of high-value chemicals [6, 10, 11]. As an example, O-demethylation of 4-PG yields the catechol moiety, a crucial intermediate in the synthesis of pharmaceuticals including the anti-cancer agent erlotinib, agrochemicals such as diethofencarb, and fragrance compounds like aldolone [10]. Hydroxylation at the α-carbon position of 4-PG yields intermediates useful for producing spicy flavor components [12]. Additionally, introducing a double bond into the propyl chain of 4-PG results in isoeugenol, a key fragrance ingredient in the cosmetic industry with potential applications as an antimicrobial agent [13, 14].

Selective oxidation of inert C–H bonds remains a significant challenge in chemistry, primarily due to the high thermodynamic stability of these bonds [15]. Conventional chemical methods for C–H functionalization are often hindered by limited selectivity and the need for harsh, environmentally unfriendly conditions. Efforts to overcome these limitations have increasingly centered on the use of transition metal catalysis and engineered biocatalysts [16,17,18,19,20].

Unspecific peroxygenases (UPOs, EC 1.11.2.1) are heme-thiolate enzymes capable of catalyzing a broad range of C–H oxyfunctionalization reactions using only hydrogen peroxide as the primary oxygen donor and reductant [21]. In contrast, cytochrome P450s (CYPs), which perform similar oxyfunctionalizations, utilize molecular oxygen as the oxygen donor. In addition, expensive nicotinamide cofactors and reductase domains or partner proteins are needed as electron sources. Reactions with CYPs can be inefficient due to the occurrence of “uncoupling” reactions resulting in loss of valuable reducing equivalents [22]. UPOs offer an attractive alternative for industrial applications due to their simplicity, efficiency, robustness, and exceptional versatility as biocatalysts [21]. These qualities make UPOs a promising candidate for the tailored functionalization of 4-PG.

UPOs tend to display dual catalytic activity, functioning as both peroxygenases (oxygenation) and peroxidases (one-electron oxidation). This dual activity depends on the formation of two key catalytic intermediates, oxo-ferry cation radical complex, called compound I (Cpd-I), and ferryl hydroxide complex, called compound II (Cpd-II). The reaction results either in incorporation of an oxygen atom into the substrate (peroxygenase activity), or in the generation of a substrate radical (A-O•) (peroxidase activity) [23]. Phenolic compounds, such as 4-PG, are prone to undergoing the peroxidase reaction because of the phenol group being susceptible to one-electron oxidation [24,25,26]. Hydrogen abstraction from the phenol (O–H) would be the preferred reaction due to a low bond dissociation energy (BDE) [27] compared to C–H bonds, and the peroxidase reaction may also be promoted by possible hydrogen bonding between the O–H group and the Cpd-I oxygen. Therefore, when exploring UPOs for valorization of compounds such as 4-PG, regioselectivity is important, but it is also essential to identify UPOs with minimal peroxidase activity.

While the biological function of UPOs remains unclear, these enzymes are known to act on a broad spectrum of substrates. UPOs are predominantly found in fungi, many of which play a key role in lignin degradation. It is therefore plausible that their native activity aids in the oxidation of small lignin units released during lignin degradation. Such oxidation could enhance the utilization of lignin subunits as a carbon source and possibly contribute to formation of humus [28,29,30]. Oxidation reactions such as O-demethylation and hydroxylation of aromatic compounds are well-documented steps in the utilization of lignin as a carbon source [28]. The involvement of UPOs in these biological processes remains speculative. In vitro experiments have demonstrated O-demethylation and cleavage of non-phenolic β-O-4 lignin model dimers by AaeUPO [31]. Further investigations, such as proteomics and genome knockout studies, are required to fully elucidate the intriguing role of these diverse and promiscuous enzymes. Nevertheless, further insight in the in vitro catalytic activities of UPOs on lignin subunits would offer valuable insights into their potential natural functions.

To gain more insight into these matters, we have assessed the activity on 4-PG for a diverse set of 19 unspecific peroxygenases, selected from phylogenetically distant clades across the phylogenetic tree. Structural comparisons were performed to identify structural features potentially underlying the observed variation in the peroxygenase:peroxidase activity ratios and the regioselectivity of the peroxygenase reaction. This study provides insights into UPO catalytic behavior and reveals the potential of using UPOs for regioselective oxidation of 4-PG.

Methods

UPO selection and phylogenetic analysis

A total of 7043 UPO sequences were retrieved from the 3DM database (Bio-Prodict BV, Nijmegen, The Netherlands). To assess the evolutionary relationships of the retrieved sequences, a phylogenetic tree was constructed. Duplicated and very short or long sequences were filtered using cd-hit, and the signal peptides were removed with SignalP 6.0 [32, 33]. The final set of 2,044 sequences were then aligned with mafft (default options) and trimmed using trimal [34, 35]. The trimmed alignment was used to build the phylogenetic tree with IQTree and modelfinder (best fit-model according to the Bayesian Information Criterion: Q.pfam+R10), using the ultrafast bootstrap analysis [36,37,38]. A total of 19 UPOs were selected from across the phylogenetic tree. These sequences were assigned to five monophyletic groups name Clades I–V. The selection criteria were biased towards well-characterized UPOs with solved crystal structures and UPOs for which recombinant expression had been shown. To include more diversity, one uncharacterized UPO (MphUPO) from a distinct clade was included. Details for the 19 selected enzymes are provided in Table S1.

UPO cloning, transformation and expression testing

Cloning and transformation

Komagataella phaffii was selected as a host organism for protein expression. The genes of interest were codon-optimized using codon usage data from the SnapGene software (GSL Biotech LLC, USA), ensuring a GC content of 40–50% (GC Content Calculator, BiologicsCorp, USA). Native signal peptides were replaced by the α-factor signal peptide [39]. Homologous regions (~30 bp) for the expression vector were added upstream and downstream of the gene fragments, which were subsequently synthesized by Twist Bioscience (USA). All target genes were then cloned into the expression vector pBSY3Z (Bisy GmbH, Austria), which contains a de-repressible/methanol-inducible PDC (peroxisomal catalase 1) promoter [40].

Genes were assembled into the vector backbone using the Gibson assembly method [41]. The vector backbone was amplified by PCR using the Q5 High-Fidelity PCR Kit (New England Biolabs, USA). Following amplification, the vector was treated with DpnI (New England Biolabs, USA) and purified using a DNA Clean-up and Concentration kit (ZymoResearch, USA). Gibson assembly was performed using the NEBuilder HiFi DNA Assembly kit (New England Biolabs, USA).

For vector propagation, chemically competent E. coli TOP10 (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) were transformed and transformants were selected on LB agar plates containing 25 µg/mL Zeocin (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Positive colonies were screened by colony PCR using the Red Taq DNA Polymerase Master Mix (VWR, USA), and sequence integrity was confirmed by Sanger sequencing (Eurofins Genomics, Germany).

Sequence-verified plasmids were linearized with SwaI (New England Biolabs, USA). Electrocompetent K. phaffii MutS (BSYBG11, Bisy, Austria) was transformed with the linearized plasmids, and successful transformants were selected on YPD agar plates containing 100 µg/mL Zeocin. As a negative control, the BSYGB11 strain was transformed with the pBSY3Z plasmid without an inserted gene (“empty” plasmid).

Expression test

For each construct, three independent colonies were selected and inoculated into 5 mL of BMD1 medium, prepared as reported by Weis et al. [42]. Cultures were incubated at 28 °C for 66 h. Once the primary carbon source was depleted, induction was initiated by adding 500 µL BMM10 medium [42]. Thereafter, 50 µL of methanol (100%) were added at 74, 90, and 98 h. Cultures were harvested at 114 h by centrifugation (5,000 g, 10 min, at 4 °C). The supernatants were filtered through a 0.22-µm filter and stored at 4 °C until further analysis. To identify the clone with the highest protein yield, an activity assay with 2,6-DMP (2,6-dimethoxyphenol, Merck, Germany) was performed on each transformant, as described below in the Section “Activity test with colorimetric assays”. Based on the results from this preliminary screening, an expression clone was selected for each UPO, which was used in further work.

UPO production and purification

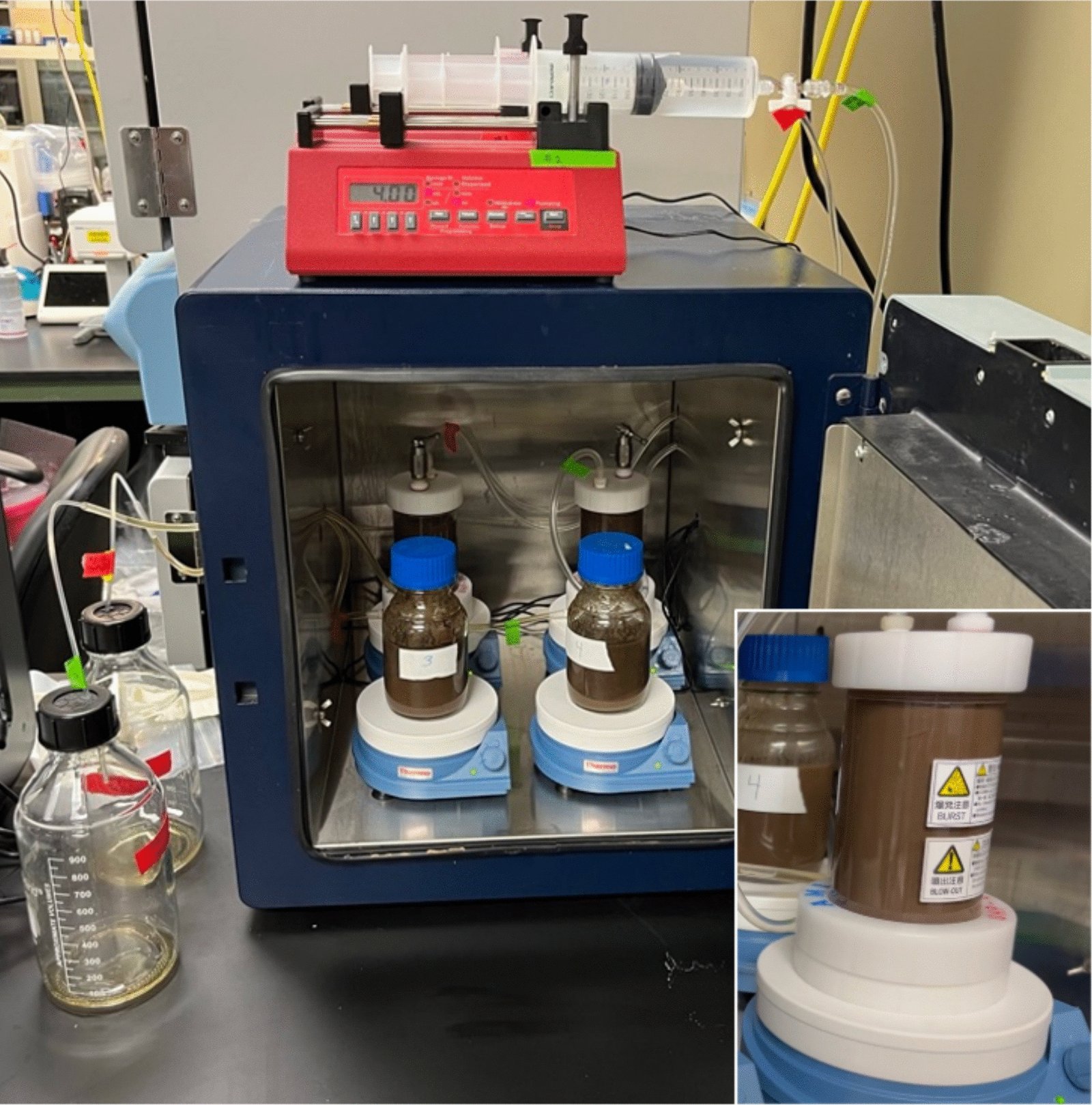

UPO production

The selected K. phaffii transformants were plated on YPD agar (100 µg/mL Zeocin) and incubated for 2 days at 30 °C. Shake flask cultivations were performed in sterile 2-L baffled Erlenmeyer flasks containing 250 mL of BMD1 medium [42], covered with cotton cloths. The medium was inoculated with approximately 1 cm2 of cellular biomass from the pre-incubated plates. Cultures were incubated at 28 °C and 250 rpm for 66 h. Induction was initiated at 66 h by adding 25 mL of BMM10 medium [42], followed by the addition of 2.5 mL of pure methanol every 12 h until 150 h. At 160 h, the culture supernatant was harvested by centrifugation (5000g, 10 min at 8 °C). The cell pellet was discarded, and the supernatant was filtered through 0.22 µm SteriTop filter units (Merck, USA). It was then concentrated fivefold and buffer-exchanged (50 mM Tris–HCl buffer, pH 7–8, adjusted based on the UPO isoelectric point) using 10 kDa tangential flow filtration (TFF) cassettes (Vivaflow, Sartorius, Germany). The concentrated supernatant was stored at 4 °C until further use.

Purification

Purification procedures varied depending on the specific UPO. UPOs, including AbrUPO-I, CmaUPO-I, MorUPO, MroUPO, PaDa-I and TteUPO, were purified using ion exchange chromatography (HiTrap Capto Q, 5 mL, Cytiva, USA). The column was pre-equilibrated in 50 mM Tris–HCl buffer (pH 7.0 or 8.0, depending on the isoelectric point of each UPO), and proteins were eluted with a 0–0.5 M NaCl gradient. In contrast, AacUPO, AbrUPO-II, AluUPO, AtuUPO, CabUPO-III, CviUPO, DspUPO-I, GmaUPO-II, HspUPO, LspUPO-II, MphUPO, PanUPO, and RneUPO were purified using hydrophobic interaction chromatography (HiTrap Phenyl HP, 5 mL, Cytiva, USA). The column was pre-equilibrated with 1 M ammonium sulfate in 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.0–8.0), and proteins were eluted using a decreasing ammonium sulfate gradient (1–0 M). Fractions exhibiting the highest Reinheitszahl values were collected and assayed using the 2,6-DMP assay. Fractions active in this assay were subsequently pooled. The partially purified proteins were subsequently concentrated and buffer-exchanged into 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.0 or 8.0, adjusted according to the UPO isoelectric point) using 10-kDa centrifugal filters (Amicon Ultra, Merck, Germany). The UPO concentration was estimated by measuring absorbance at the Soret band, using the MroUPO extinction coefficient of ε=115 mM⁻1 cm⁻1 as a reference [43], assuming similar values for all UPOs.

Activity test with colorimetric assays

All activity assays were conducted in 96-well microplates, with each reaction in a total volume of 200 µL. Reactions were performed at room temperature and monitored using a microplate reader (Varioskan Lux, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) with shaking between readings. Each assay included a background control and a blank. The background control consisted of the concentrated and buffer-exchanged supernatant from the “empty” K. phaffii culture (transformed with a plasmid lacking the UPO gene), while the blank consisted of the reaction mixture with Milli-Q water instead of UPO.

For the ABTS (2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid), Merck, Germany) assay, a concentration of 0.05 µM UPO was employed (concentration determined using the Soret band, as described above), and the final concentrations in the reaction mixture were 0.5 mM ABTS, 1 mM H₂O₂, and 100 mM citric acid buffer (pH 4.5). Absorbance was measured at 405 nm for 10 min. For the 2,6-DMP assay, a concentration of 0.1 µM UPO was employed, and the final concentrations were 0.5 mM 2,6-DMP, 1 mM H₂O₂, and 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). Absorbance was measured at 469 nm for 10 min. For the NBD (5-nitro-1,3-benzodioxole, Merck, Germany) assay, a concentration of 0.05 µM UPO was employed, and the final concentrations were 0.5 mM NBD, 1 mM H₂O₂, and 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). Absorbance was measured at 425 nm for 10 min. For the 4-NA (4-nitroanisole, Merk, Germany) assay, a concentration of 0.05 µM UPO was employed, and the final concentrations were 0.5 mM 4-NA, 1 mM H₂O₂, and 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). Absorbance was measured at 410 nm for 10 min. For the naphthalene assay, a concentration of 0.1 µM UPO was employed, and the final concentrations were 1 mM naphthalene (dissolved in acetone, 10% final acetone concentration), 1 mM H₂O₂, and 100 mM citric acid buffer (pH 4.5). Absorbance was measured at 324 nm for 10 min. Initial rates were determined using the linear region of the curve.

Activity for 4-propylguaiacol

Activity assays for 4-PG were conducted at three different pH values, using the following buffers: 50 mM ammonium acetate, pH 3.5 or pH 5.5, and 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate, pH 8.0. Each reaction (210 µL) contained 1 µM UPO, 2 mM 4-PG (dissolved in acetonitrile, 0.5% final concentration), and 2 mM H₂O₂. To evaluate the occurrence of one-electron oxidations and potential coupling reactions, assays were performed with and without the addition of a radical scavenger (16 mM ascorbic acid). Reactions were incubated for 1 h at 25 °C with continuous agitation at 700 rpm. This incubation period was selected to achieve near-complete substrate conversion, thereby enabling comprehensive analysis of product profiles. The reactions were subsequently analyzed by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS), as described in the following section.

Analysis by GC–MS

Reaction products were analyzed by GC–MS. Firstly, samples were extracted with ethyl acetate at a 1:1 (v/v) ratio. The mixture was vortexed for 15 min and then centrifuged at 5000×g for 10 min to achieve phase separation. The organic phase was collected and prepared for GC–MS analysis. Gas chromatography was performed on a TRACE™ 1310 GC (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) equipped with a Single Quadrupole Mass Spectrometer (ISQ QD, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). To inject the sample, an AI/AS 1310 Series Autosampler was utilized (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), injecting 1.0 μL with a split ratio of 1:10. The GC method employed a linear temperature program with an initial hold at 80 °C for 5 min, followed by a ramp to 180 °C at 20 °C/min and a 5-min hold at 180 °C. This was followed by a gradient from 180 °C to 280 °C at 20 °C/min, with a final hold at 280 °C for 5 min. Helium was used as the carrier gas at a constant column flow rate of 1 mL/min on a VF-5 ms column (Agilent J&W, 0.250 mm diameter, 30 m length, 0.25 µm film thickness). Electron ionization was used as the ionization method (70 eV) with a mass range of m/z 50–600 and an ion source temperature of 250 °C. Products were identified by matching retention times and mass spectra obtained using commercial standards (2-methoxy-4-(prop-1-en-1-yl)phenol, 1a, Sigma-Aldrich; 4-propylbenzene-1,2-diol, 1b, MedChemExpress; 4-(1-hydroxypropyl)-2-methoxyphenol, 1d, MedChemExpress; and 4-methoxy-6-propylbenzene-1,3-diol, 1e, MedChemExpress). Quantitative analyses were performed using external calibration curves, with all standard curves achieving linear regression values (R2>0.98). Standard for compound 1c (4-Hydroxy-2-methoxy-4-propylcyclohexa-2,5-dien-1-one) with an m/z value of 182 was unavailable. Therefore, identification was performed by 1H NMR (as described in the Section below), and quantification was conducted using the calibration curve of the structural isomer 1d, assuming a comparable response factor.

Analysis by 1 H nuclear magnetic resonance

Compound 1c was identified as the main product from a crude 1H spectrum. The 1H NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker 400 MHz spectrometer at 25 °C. Samples were prepared in CDCl3 (~0.6 mL) and analyzed using a 90° pulse sequence (16 scans, spectral width: 20 ppm, acquisition time: 4 s, relaxation delay: 10 s). The receiver gain was set automatically. Chemical shifts were referenced to the residual solvent peak (δ=7.26 ppm). Data were processed using Bruker TopSpin 4.3.0. Due to peak overlap, alkyl shifts were assigned using selective TOCSY experiments. The chemical shifts and coupling constants are in agreement with those reported in previous studies [44]: 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 0.93 (t, J=7.34 Hz, 3H), 1.30 (m, 2H), 1.78 (m, 2H), 3.69 (s, 3H), 5.71 (d, J=2.68 Hz, 1H), 6.19 (d, J=10.04 Hz, 1H), 6.82 (dd, J=2.72, 10.04 Hz, 1H).

Structural comparisons

Structural models were obtained from either available crystal structures or AlphaFold3 predictions [45]. The heme group and the magnesium ion were incorporated in all models. Docking simulations were conducted using the Vina algorithm in YASARA Structure (YASARA Biosciences GmbH, Austria), with energy-minimization of all structures prior to docking. A preliminary simulation was conducted to identify residues within 4–5 Å of the substrate by selecting solutions where the substrate was positioned near the heme. In the final docking simulations, the side chains of the identified residues (6–10 residues) were set as flexible. The docking experiments generally produced multiple solutions, often with similar energy. The solutions presented, primarily for illustrative purposes, were selected based on observed product profiles, where the oxidized carbon was positioned close to the heme (3.5–4 Å). The selected solutions were among the top seven out of twenty, each exhibiting a binding energy of at least 20.72 kJ/mol (Table S2). Caver (Caver Analyst 2.0, Masaryk University, Czech Republic) was employed to analyze and visualize the access channels of the different UPOs. Structural comparisons were performed using PyMOL (The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Schrödinger, LLC).

Results

Phylogenetic clustering of selected UPOs

A phylogenetic tree was constructed using the 3DM-derived sequences to assess their evolutionary relationships (Fig. 1). A total of 19 UPOs were selected from across the phylogenetic tree. These sequences were assigned to five monophyletic groups name Clades I–V, which are indicated in the tree. Note, these clades do not encompass the entire sequence space represented in the phylogenetic tree, as their assignment was intended solely to group the UPOs studied in this work. The sequences of the 19 selected proteins exhibited pairwise identities ranging from 20 to 95% (Figure S1). UPOs within Clade I (CabUPO-II, CmaUPO-I, GmaUPO-II, PaDa-I, and LspUPO-II) are so-called “long UPOs” with a molecular weight of approximately 38 kDa. The UPOs in this clade all belong to the Basidiomycota phylum. Conversely, Clades II through V contain UPOs known as “short UPOs” with a molecular weight of approximately 27 kDa. Clade II (CviUPO and PanUPO) and Clade III (MorUPO and MroUPO) also comprise UPOs restricted to the Basidiomycota phylum. Clades IV (MphUPO) and V (AbrUPO-I, AbrUPO-II, AluUPO, AtuUPO, AacUPO, TteUPO, HspUPO, RneUPO, and DspUPO-I) contain UPOs belonging to the Ascomycota phylum. The phylogenetic tree highlights the notable evolutionary divergence among the five clades examined in this study. Figure S2 shows conservation patterns for 19 selected active site residues both within and among the clades, and reveals clear, conserved differences between clades.

Phylogenetic clustering of selected UPOs into five distinct clades. The tree topology was generated from 2,044 sequences using IQTree. The 19 selected UPOs (see Table S1 for detailed information) were classified into five monophyletic groups, designated as Clades I–V, as indicated on the phylogenetic tree. Note that these clades do not cover the entire sequence space represented in the phylogenetic tree, as their assignment was intended solely to group the UPOs studied in this work. The five clades sampled in the present study encompass UPOs of the Ascomycota and Basidiomycota families and are color coded as follows: Clade I (purple), Clade II (cyan), Clade III (gray), Clade IV (orange), and Clade V (green). Long and short UPO families are separated by dashed lines

Assessing UPO activity using colorimetric assays

Initial screening of three colonies per transformant showed that supernatants were active on 2,6-DMP in almost all cases (Figure S3), and the clone of each UPO with highest activity was used to produce at larger scale.

After partial purification and determination of the UPO concentration using the Soret band, standard colorimetric assays were performed to evaluate enzymatic activity and confirm UPO stability several weeks after purification and following completion of the 4-PG reactions. Peroxidase activity was measured using the peroxidative substrates ABTS and 2,6-DMP. Peroxygenase activity was evaluated using NBD, naphthalene, and 4-NA as substrates. For each substrate, the highest reaction rate (absorbance change over time) was defined as 100%, and the activities of the remaining UPOs were expressed as percentages relative to this value.

All selected UPOs exhibited activity in at least three of the colorimetric assays, demonstrating both peroxidase and peroxygenase activity (Figure S4). As a background control, the concentrated and buffer-exchanged supernatant from a K. phaffii culture transformed with the “empty” plasmid was used, showing no activity in any of the assays. The assays with ABTS and 2,6-DMP confirmed peroxidase activity for all UPOs. All UPOs except LspUPO-II exhibited activity on NBD. For naphthalene, no activity was detected for AbrUPO-II, CviUPO, PanUPO, and TteUPO. In the 4-NA assay, used as a surrogate for demethylation reactions, only AbrUPO-I, AluUPO, AtuUPO, DspUPO-I, and HspUPO showed detectable activity. Importantly, these analyses revealed clear differences between the UPOs, both in terms of general catalytic efficiency as deduced from overall product levels and, importantly, in terms of observed substrate preferences (Figure S4; the relative levels of the five products per UPO varies largely between the UPOs).

Activity of UPOs for 4-propylguaiacol

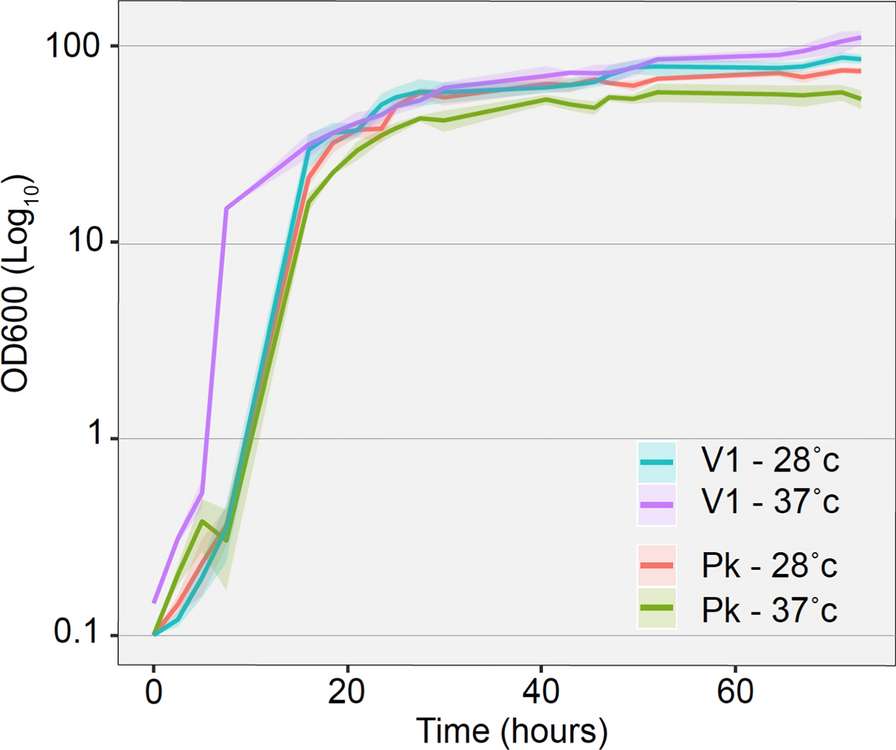

UPOs offer a sustainable alternative for the selective oxyfunctionalization of 4-PG. However, the phenolic moiety of this substrate increases its susceptibility to unwanted one-electron oxidations (peroxidase activity), resulting in the formation of phenoxy radicals [23]. To evaluate the selected 19 UPOs, their activity on 4-PG was screened at three pH values (3.5, 5.5, and 8.0), in the presence or absence of ascorbic acid, a known radical scavenger. Substrate and products concentrations were determined after 1 h incubation using external calibration curves. For 1c, a structural isomer was used for calibration. To provide a more comprehensive understanding of the product and substrate distribution, percentages of each compound were calculated relative to the total amount of substrate initially added. UPOs converted 4-PG to varying extents, with all of enzymes converting more than 50% of the substrate. In nearly all reactions, the peroxidase activity predominated over peroxygenase activity (Fig. 2). Five distinct monomeric products arising from peroxygenase activity were identified using GC–MS (Figure S5 shows GC–MS chromatograms illustrating different reactions), involving hydroxylation at different positions (1c, 1d and 1e), O-demethylation (1b) or formation of a double bond (1a). Figure 3 shows a heatmap for the product profiles across the UPO panel at pH 8.0, while similar data for the reactions at pH 3.5 and 5.5 are shown in Figures S6 and S7, respectively. Substrate consumption and product formation were not observed in the negative control reactions.

Fractions of peroxygenase conversion, peroxidase conversion and non-converted substrate (4-PG) in reactions without ascorbic acid for 19 different UPOs at three different pH values. The y-axis represents the percentage relative to the total amount of substrate added. Compound concentrations were determined using external calibration curves made with commercial standards and compounds were analyzed using GC–MS. The peroxygenase activity (green) represents the sum of all detected monomeric products. The peroxidase activity (red) represents the fraction of consumed substrate minus the fraction of quantified peroxygenase products. See Fig. 3 and Figs. S6 and S7 for the underlying data and more details on quantification. The various phylogenetic clades selected in this study (Fig. 1) are indicated in the top row of the figure

Heatmap for the catalytic activity of 19 UPOs on 4-propylguaiacol at pH 8.0, in the absence or presence of ascorbic acid. Values represent the percentages of products and remaining substrate (orange) relative to the total amount of substrate added. In the presence of ascorbic acid, in a limited number of reactions the total mass balance was not fully quantified, which can be attributed to peroxidase-derived products that were not scavenged by ascorbic acid (e.g., dimers observed in reactions with AtuUPO and HspUPO) or to compounds that remained undetectable by GC–MS. Color intensities are proportional to the values, with darker tones corresponding to higher values. Each column represents a different compound, as indicated at the top of the figure. Compound concentrations were determined by external calibration curves using commercial standards and analyzed via GC–MS. Standard for compound 1c (m/z 182) was not available; consequently, it was identified by 1H NMR and quantified using the calibration curve established for compound 1d. Some of the products appeared as dimers identified by the m/z 330 in GC–MS. The values for the dimers do not represent actual product levels but represent the peak area of dimer peaks relative to the peak area of the total amount of substrate added. Thus, these are rather arbitrary numbers that should only be used for comparing UPOs, and not for absolute product quantification or calculating mass balances. Also note that other, non-detected products could be generated in some of the reactions even in reactions with ascorbic acid. The UPOs are grouped according to their respective phylogenetic clades (Fig. 1), as indicated by the color code to the left of the figure. Reaction conditions: Final volume of 210 µL, 1 µM UPO, 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate buffer (pH 8.0), 2 mM 4-propylguaiacol, 2 mM hydrogen peroxide, and 16 mM ascorbic acid, where indicated. The reactions were incubated at 25 °C with shaking at 700 rpm for 1 h

Peroxidase and peroxygenase activity profiles

Peroxidase activity leads to the one-electron oxidation of the phenolic hydroxyl group, generating phenoxy radicals that can be delocalized and undergo coupling reactions, leading to the formation of dimers and polymerization [24]. In the absence of ascorbic acid, substrate dimers (m/z 330) at two distinct retention times were detected by GC–MS, and some of the reaction solutions developed a red-brownish color, indicative of polymerization. Peroxidase activity was determined as the difference between the amount of consumed substrate and the amount of detected and quantified monomeric products resulting from peroxygenase reactions. While peroxygenase activity was determined as the sum of all detected monomeric products. Of note, the peroxygenase-to-peroxidase activity ratio varied among the UPOs (Fig. 2). Some UPOs, such as GmaUPO-II and AtuUPO at pH 3.5 and 8.0, respectively, were highly selective toward peroxygenase activity and this ratio approached 1, whereas the peroxygenase activity of others, such as CabUPO-II and CviUPO, was hardly detectable.

In the presence of ascorbic acid, no product dimers were detected for most UPOs, indicating effective scavenging of phenoxy radicals and prevention of radical coupling (Fig. 3, and Figures S6 and S7). Additionally, the percentage of unconverted substrate was considerably higher—exceeding 50% for most UPOs—likely because ascorbic acid intercepts phenoxy radicals, regenerating the original substrate rather than allowing these radicals to undergo coupling and, subsequent, polymerization. This scavenging effect reduces the net substrate consumption via polymerization pathways. Moreover, an increase in peroxygenase product formation was observed in some cases (Figure S8), which may be attributed both to the higher availability of substrate due to reduced polymerization and to the ability of ascorbic acid to scavenge radicals on further one-electron oxidation of peroxygenase products. Several UPOs exhibited notable peroxygenase activity compared to peroxidase, including GmaUPO-II (53% peroxygenase products relative to the total amount of substrate added, at pH 5.5), AbrUPO-I (61%), AluUPO (82%), AtuUPO (70%), HspUPO (62%), and DspUPO-I (49%). Interestingly, it has recently been reported that, when supplied with large amount of ascorbic acid, UPOs may employ a monooxygenase mechanism [46]; if it would happen, such a reaction would contribute to the formation of (in this case apparent) peroxygenase products.

Comparison of UPOs across different clades revealed a discernible trend in peroxygenase activity, especially for the reactions with ascorbic acid (Figure S8). Peroxygenase activity toward 4-PG was most prominent in UPOs from Clade V, while UPOs from other clades exhibited minimal peroxygenase activity. These findings suggest that UPOs within the same clade may share structural features that enhance peroxygenase activity toward 4-PG as will be further examined in the next section. An exception is GmaUPO-II from Clade I, which displayed notable peroxygenase activity (53% monomeric products at pH 5.5 with ascorbic acid; Figure S8) compared to other UPOs in the same clade, and will be discussed further in the following section.

Regarding the influence of pH on peroxygenase:peroxidase ratios, no consistent pattern emerged across the examined pH levels (Fig. 2 and Figure S8). Nevertheless, the activity of certain UPOs was pH-dependent. For example, AluUPO and AtuUPO exhibited elevated peroxygenase activity at pH 8.0, whereas RneUPO and GmaUPO-II showed higher peroxygenase activity at both pH 3.5 and 5.5 compared to pH 8.0.

Peroxygenase activity: monomeric products and regioselectivity

Analysis of the peroxygenase products generated by the tested UPOs revealed different regioselectivities (Fig. 3, and Figures S6 and S7), resulting in the formation of at least one of five different products: 2-methoxy-4-(prop-1-en-1-yl)phenol (1a); 4-propylbenzene-1,2-diol (1b); 4-hydroxy-2-methoxy-4-propylcyclohexa-2,5-dien-1-one (1c), 4-(1-hydroxypropyl)-2-methoxyphenol (1d), and 4-methoxy-6-propylbenzene-1,3-diol (1e).

For each UPO, the highest yield for a specific peroxygenase product is summarized in Figure S9 which provides the product yielded, the regioselectivity and an overview of the reactions (type of UPO, pH, ascorbic acid or not). Interestingly, some UPOs from the same phylogenetic clade exhibited distinct regioselectivities (Fig. 3), suggesting differences in the catalytic centers and/or the substrate access channel. However, closely related UPOs, such as AtuUPO and AluUPO—with 96% sequence identity (Figure S1)—displayed the same regioselectivity, with a marked preference for compound 1c.

Product 1a results from the formation of a double bond on the propyl chain of 4-PG, which occurred as a minor side reaction for most UPOs. RneUPO exhibited the highest fraction of 1a at pH 5.5 with ascorbic acid (7%). This catalytic activity has not been previously reported for UPOs and maybe is a result of elimination of H2O from 1d.

Product 1b, resulting from O-demethylation of 4-PG, was detected in varying yields across the different UPOs. AbrUPO-I showed the highest yield at pH 8.0 in presence of ascorbic acid (42%). The regioselectivity of this reaction, defined as the amount of a specific peroxygenase product relative to the total amount of peroxygenase products, was 61%. O-Demethylation via UPOs has been previously described, occurring through hydroxylation at the methyl carbon to form a highly unstable hemiacetal intermediate. This intermediate rapidly undergoes spontaneous cleavage, releasing the methyl group as formaldehyde [47].

Product 1c is likely formed through hydrogen abstraction at the phenol group, followed by resonance delocalization of the resulting radical and subsequent hydroxylation at the former para position by Cpd-II, or alternatively, addition of a water molecule. This transformation disrupts aromaticity, leading to the formation of a ketone at the original position of the phenol group. AluUPO and AtuUPO exhibited the highest yields for compound 1c at pH 8.0 in the presence of ascorbic acid, converting 62% (76% regioselectivity) and 67% (96% regioselectivity) of the substrate to 1c, respectively (Figure S9).

Products 1d and 1e result from hydroxylation of the substrate at two distinct positions: at the α-carbon of the propyl chain, and at the meta position on the benzene ring, respectively. RneUPO showed the greatest yield of 1d, at pH 3.5 in the absence of ascorbic acid (33%, with 100% regioselectivity, Figure S9). HspUPO yielded the highest amount of compound 1e, at pH 5.5 in the presence of ascorbic acid (23%, with 38% regioselectivity, Figure S9).

While we could not see a systematic impact of the pH on the peroxygenase-to-peroxidase activity ratio (see above), the regioselectivity of the peroxygenase reactions was influenced by pH, with distinct trends observed across different UPOs (Fig. 3 and Figures S6 and S7). Low pH values seemed to favor double bond formation at the propyl chain (1a), O-demethylation (1b), with the exception of AbrUPO-I, and hydroxylation at the α-carbon of the propyl chain (1d). As stated previously, the formation of 1a may be the result of H2O elimination from 1d, which would be favored by a low pH. Conversely, hydroxylation at the para-position of the benzene (1c) was enhanced at pH 8.0.

In the presence of ascorbic acid, yields were consistently higher for all peroxygenase products—except for 1d at pH 3.5 and 5.5. This latter exception could be attributed to ascorbic acid acting as a competing substrate under these conditions. Interestingly, O-demethylation products (1b) and ring hydroxylation products (1e) were undetectable in the absence of ascorbic acid (except for AbrUPO-I at pH 5.5). This suggests that the presence of a second hydroxyl group on the benzene ring, resulting from an initial peroxygenase reaction, facilitates subsequent one-electron oxidations. In the presence of ascorbic acid, such one-electron oxidations would be reverted, keeping the product of the initial peroxygenase reaction intact. An explanation for such increased susceptibility may lie in a decrease in the redox potential as the number of hydroxyl substitutions on the benzene ring increases, which would facilitate oxidation of the phenolic hydroxyl groups [3, 48]. To test for this, compounds 1b and 1e were used as substrates in reactions without ascorbic acid. These reactions resulted in complete substrate consumption with no detection of products in the GC–MS analyses (data not shown). Instead, a brown-reddish color emerged, suggesting excessive peroxidase activity leading to polymerization reactions (Figure S10).

In summary, several of the UPOs demonstrated promising performance for the oxyfunctionalization of 4-PG, achieving notable product yields and regioselectivity. Interestingly, the regioselectivity varied considerably, even among UPOs within the same clade. This suggests differences in the catalytic center and/or substrate access channel, which are explored below.

Structural comparisons

This section explores the structural differences that may explain the varying peroxidase and peroxygenase activities among the selected subset of UPOs. The selected UPOs represent phylogenetically distant clades and exhibit substantial sequence diversity, with pairwise sequence identities ranging from 20 to 95% (Figure S1). This sequence variability is reflected in significant differences in the residues shaping the substrate-binding pockets and the catalytic centers (Figure S2). Figure 4 shows representative UPOs from each clade with known crystal structures, and the AlphaFold3 model for MphUPO. Even a cursory inspection of these structures reveals pronounced differences in the architecture of the catalytic centers and access channels among these UPOs from distinct clades.

Overview of the catalytic centers and substrate access channels for representative UPOs from the five clades: PaDa-I (A), CviUPO (B), MroUPO (C), MphUPO (D), and HspUPO (E). The docking solutions presented (4-PG in black) were selected primarily for illustrative purposes, based on observed product profiles, where the oxidized carbon was positioned close to the heme. The upper panels, labeled 1, show active site residues within 5 Å of the docked substrate, which are shown as sticks and color-coded according to their chemical properties (aromatic in green, aliphatic in red salmon, hydroxylic in magenta, sulfur-containing in yellow, amidic in light-blue, basic in cyan, and acidic in orange). The lower panels, labeled 2, show the protein surface in gray, while the access channel, calculated using Caver, is shown in cyan. The structures shown are PaDa-I (PDB ID: 6EKZ), CviUPO (PDB ID: 7ZCL), MroUPO (PDB ID: 7ZBP), MphUPO (AlphaFold model), and HspUPO (PDB ID: 7O1R)

Clade I comprises long UPOs that primarily exhibit peroxidase activity toward 4-PG, except for GmaUPO-II, which shows remarkable peroxygenase activity (Fig. 2). Examination of the access channel reveals a broad channel for all UPOs in this clade, with the exception of GmaUPO-II (Fig. 4A; additional UPOs shown in Figure S11). Structural comparison between GmaUPO-II and PaDa-I (Fig. 5), which share 73% sequence identity, revealed a more restricted substrate entrance in GmaUPO-II, primarily due to Phe302 (corresponding to Pro277 in PaDa-I), and a narrower access channel caused by the presence of bulky residues.

Comparison of access channel and active sites between PaDa-I (A) and GmaUPO-II (B) from Clade I. Residues that differ between the two enzymes are labeled. The access channel surfaces, calculated using Caver, are depicted in pale orange to highlight differences in cavity size and shape. The structures used are for PaDa-I (PDB ID: 6EKZ) and GmaUPO-II (AlphaFold model). Approximate access entrance points for the substrates are indicated by a black arrow. The figure highlights the difference in the size of the access channel between two UPOs from the same clade

UPOs from Clade V demonstrated marked peroxygenase activity toward 4-PG (Fig. 3 and Figure S8). Structural analysis revealed a distinct feature in their catalytic centers: next to a relatively narrow substrate channel (Fig. 4E), these UPOs contain an “aliphatic pocket” close to the heme group that likely restricts substrate binding options and may facilitate binding in a pose that promotes the peroxygenase reaction (Fig. 6 and Figure S12). This aliphatic pocket is highly conserved across Clade V UPOs comprising residues I73, L77, L81, A183, I187, and L228 (HspUPO numbering), with minor variations at certain positions (Figure S2). Docking studies suggested that the propyl chain of 4-PG interacts with this aliphatic pocket. Moreover, Phe176 (HspUPO numbering), a highly conserved residue within Clade V, likely interacts with 4-PG through π-stacking interactions (Figure S12). Thus, all Clade V UPOs appear to share conserved features that characterize their catalytic centers and may determine their activity toward 4-PG: an aliphatic pocket and a phenylalanine residue. These features are illustrated in Fig. 7, with HspUPO serving as a representative structure.

Comparison of catalytic pocket surfaces for UPOs from different clades. One representative UPO was selected from Clades I–IV. UPOs with the highest peroxygenase yields were selected from Clade V. The aliphatic pocket in UPOs from Clade V is highlighted in orange. The docking solutions (4-PG in black) were selected among energetically favorable poses primarily for illustrative purposes, based on observed product profiles, where the oxidized carbon was positioned close to the heme. The structures used include PaDa-I (PDB ID: 6EKZ), CviUPO (PDB ID: 7ZCL), MroUPO (PDB ID: 7ZBP), and HspUPO (PDB ID: 7O1R); the remaining structures were modeled using AlphaFold3. The figure highlights how the aliphatic pocket may assist the positioning of 4-PG in vicinity to the heme for the peroxygenase reaction

Key elements of the catalytic center in Clade V UPOs, illustrated using HspUPO as a representative (PDB ID: 7O1R). Highlighted are shared characteristics in Clade V UPOs, the conserved phenylalanine (Phe176), and the aliphatic pocket (shown in orange). The conserved acid–base pair (His110 and Glu180) are also represented. The docking solution (4-PG in black) was selected primarily for illustrative purposes, based on observed product profile, where the oxidized carbon was positioned close to the heme

In contrast to Clade V, UPOs from other clades (I–IV), which primarily exhibit peroxidase activity toward 4-PG, feature a funnel-shaped access channel and lack the aliphatic pocket (Fig. 6). The funnel-shaped cavity features a narrow base, which may restrict the proximity of 4-PG to the heme, thereby decreasing the probability of the peroxygenase reaction, as close distance of approximately 4 Å, between the reactive hydrogen and the heme iron is required for efficient rebound to Cpd-II [49]. Conversely, Clade V UPOs possess an aliphatic pocket that provides sufficient space for 4-PG to remain in closer contact with the heme, potentially enhancing peroxygenase activity. For instance, CviUPO (Clade II) features four bulky residues (Ile61, Phe88, Glu162, and Lys165) in the immediate vicinity of the heme, which could hinder close interaction between 4-PG and the heme (Figure S13A). In Clade III, analysis of MroUPO revealed the absence of an aliphatic pocket. Instead, this enzyme features a funnel-shaped cavity primarily composed mainly of aliphatic residues, but lacking the aliphatic pocket (Figure S13C). Meanwhile, MphUPO (Clade IV) contains Met61, which introduces steric hindrance, preventing 4-PG from establishing close contact with the heme (Figure S13B).

In summary, structural differences among UPOs seem to correlate with their distinct peroxidase and peroxygenase activity profiles and this is particularly visible (and consistent) when examining Clades I and V. Clade V UPOs, which exhibit substantial peroxygenase activity, feature a unique aliphatic pocket in their catalytic centers. In contrast, UPOs from other clades predominantly possess funnel-shaped cavities and showed neglective peroxygenase activity. And exception was GmaUPO-II from Clade I, which also displays enhanced peroxygenase activity and features a constrained entrance and a narrow access channel.

Discussion

The oxyfunctionalization of the monolignol 4-PG by UPOs holds significant industrial potential, as the resulting compounds can serve as versatile scaffolds. For example, O-demethylation of 4-PG (1b) yields the catechol moiety, a crucial intermediate in the synthesis of pharmaceuticals, agrochemicals, and fragrance compounds [10]. Furthermore, 4-PG is an interesting model substrate, given its combination of phenolic, methoxy and hydrophobic properties. Currently, biocatalytic applications of UPOs remains a challenge due to the competing peroxidase activity on substituted phenolic substrates such as 4-PG [23,24,25,26]. During catalysis, hydrogen atom abstraction from the phenol (O–H) is the preferred reaction due to a low bond dissociation energy (BDE) [27] compared to C–H bond activation, and the peroxidase reaction may further be promoted by possible hydrogen bonding between the O–H group and the Cpd-I oxygen. However, the topology of the substrate-binding pocket and the chemical properties of the amino acids near the active site can modulate these inherent chemical preferences by influencing critical factors such as diffusion dynamics of substrates, products and intermediates, substrate orientation, intermediate stabilization, and the redox potential of the phenolic group.

The results presented above suggest that a constrained access channel and catalytic center defined by an aliphatic pocket promote the peroxygenase reaction. These constraints may retain the substrate in close proximity to the active site for an extended period, favoring hydrogen abstraction and oxygen rebound (peroxygenase reaction). In contrast, a broad, funnel-shaped access channel and catalytic center could result in rapid substrate entry and product exit, which could favor peroxidase activity. Furthermore, a spatially restricted catalytic environment may enforce specific substrate positioning, promoting H-abstraction at C–H over O–H bonds, while a less restrictive catalytic center may accommodate multiple substrate orientations eventually favoring the energetically favorable hydrogen abstraction from phenols. Docking simulations provided multiple energetically favorable binding solutions across the tested UPOs. Therefore, while docking results should be interpreted with caution, poses in accordance with the observed product profile suggest that the aliphatic pocket of Clade V UPOs can accommodate the propyl chain of 4-PG, facilitating close contact with the heme (Figs. 6 and S12). In addition, a confined hydrophobic catalytic center will limit interactions with water molecules, which otherwise would help lowering the reduction potential of phenolic substrates by stabilizing radical species through hydrogen bonding, thereby enhancing their susceptibility to oxidation of the phenolic group. From previous studies, it is well known that one-electron oxidation reactions may be facilitated by hydrogen bonding between the substrate and polar residues or the protein backbone [50, 51]. For instance, in the interaction of ferulic acid (FA) with horseradish peroxidase (HRP), the phenolic oxygen of FA forms a hydrogen bond with the guanidinium group of an arginine residue [52].

The selected UPOs represent five distinct phylogenetic clades, encompassing both long (Clade I) and short (Clades II–V) UPOs. Structural analysis revealed a defining feature among the Clade V UPOs—namely, the presence of an aliphatic pocket that correlates with the substantial peroxygenase activity observed in Clade V UPOs. The aliphatic pocket may accommodate the hydrophobic propyl chain of the substrate (Fig. 6 and Figure S12), thereby facilitating productive positioning for oxygen transfer and enhancing peroxygenase activity. Notably, this structural feature is absent in UPOs with low peroxygenase activity. Conversely, MphUPO (Clade IV) which shares 49% sequence identity with TteUPO from Clade V (Figure S1), exhibits a markedly different functional profile. MphUPO lacks the aliphatic pocket and contains Met61 at the active site (Figure S13B), correlating with negligible peroxygenase activity, whereas TteUPO possesses the aliphatic pocket and displays substantial peroxygenase activity. Additionally, Clade III UPOs such as MroUPO displays an overall aliphatic character in the catalytic center similar to Clade V UPOs (Figure S2 and Figure S13C) but lacks the defined aliphatic pocket and exhibit minimal peroxygenase activity. Instead, these enzymes feature a funnel-shaped cavity.

Notably, GmaUPO-II from Clade I also demonstrated remarkable peroxygenase activity compared to other Clade I UPOs, despite their high sequence similarity—for instance, GmaUPO-II shares 73% sequence identity with PaDa-I (Figure S1). Structural comparisons within Clade I revealed that GmaUPO-II possesses a more restrictive access channel entrance and a more constrained access channel (Fig. 5 and Figure S11), while lacking the aliphatic pocket. These findings underpin that a more constrained active-site topology is one key factor in enhancing peroxygenase activity. Moreover, previous studies on PaDa-I (Clade I) have employed mutagenesis to elucidate its peroxidase activity with ABTS [53]. These studies identified a loop located at the entrance of the heme access channel as a key determinant of peroxidative activity. This finding aligns with structural comparisons between GmaUPO-II and PaDa-I, suggesting that differences in the peroxygenase-to-peroxidase ratio may be linked to variations in the access channel entrance—specifically, a more restricted entry and the presence of bulkier residues in GmaUPO-II may be related to its more pronounced peroxygenase activity on 4-PG.

In addition to the topology of the catalytic center, the chemical nature of residues is obviously crucial and may also contribute to the peroxidase-to-peroxygenase ratio. For example, CviUPO in Clade II contains a lysine residue (Lys165) in its catalytic center. Docking analysis suggests the formation of a hydrogen bond between the phenolic oxygen of the substrate and the amine group of Lys165, with a bond length of 2.5 Å (Figure S13A). This could promote peroxidase activity, in accordance with previous studies on HRP, and the experimental results indeed show that CviUPO primarily exhibits peroxidase activity [52].

In most cases, the reactions with 4-PG in the absence of ascorbic acid predominantly resulted in one-electron oxidations. This observation suggests that monolignols are unlikely to be the native substrates of UPOs, as peroxygenase activity, primarily oxygenation reactions, would be expected to dominate due to the metabolic significance of such reactions [28]. Nevertheless, several UPOs showed promising activities on 4-PG, with UPOs from Ascomycota (Clade V) displaying a greater propensity for oxygenation reactions. Further studies are needed to determine the native activities and biological roles of these UPOs.

Conclusions

Our study provides a functional mapping of a broad UPO-sequence space, highlighting these enzymes as potential biocatalysts for the tailored functionalization of the industrially relevant substrate 4-PG. Notably, various UPOs—such as AbrUPO-I, AtuUPO, RneUPO, and HspUPO—demonstrated promising product yields and regioselectivities for compounds 1b–1e, while not yet optimized, indicate strong potential for future industrial application. These reactions required the presence of ascorbic acid except for the reaction with RneUPO, which is not a limitation since ascorbic acid is widely used in industrial applications due to its affordability [54, 55]. Our comparative analysis—supported by experimental product profiles and structural data—suggest that a more constrained active-site topology, which facilitates tighter interactions with 4-PG, may contribute to the observed enhancement in peroxygenase activity. In particular, UPOs from Clade V, demonstrating remarkable peroxygenase activity contain a unique aliphatic pocket in their catalytic centers. While these correlations are supported by comparative structural and activity data, targeted mutagenesis studies will be valuable to confirm the role of these structural features. Overall, this study provides valuable structural and functional insights into UPOs with enhanced peroxygenase activity toward phenolic substrates, paving the way for their future biotechnological application.

Availability of data and materials

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

-

Albuquerque B, Heleno S, Oliveira MBP, Barros L, Ferreira ICF. Phenolic compounds: current industrial applications, limitations and future challenges. Food Funct. 2021;12:14–29. https://doi.org/10.1039/D0FO02324H.

-

Vermerris W, Nicholson R. Chemical properties of phenolic compounds. In: Vermerris W, Nicholson R, editors. Phenolic compound biochemistry. Dordr.: Springer . 2006. p. 35–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-5164-7_2

-

Li X, Gao Y, Xiong H, Yang Z. The electrochemical redox mechanism and antioxidant activity of polyphenolic compounds based on inlaid multi-walled carbon nanotubes-modified graphite electrode. Open Chem. 2021;19:961–73. https://doi.org/10.1515/chem-2021-0087.

-

Wright JS, Johnson ER, DiLabio GA. Predicting the activity of phenolic antioxidants: theoretical method, analysis of substituent effects, and application to major families of antioxidants. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:1173–83. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja002455u.

-

Dave D. Integrated cumene-phenol/acetone-bisphenol A- Part II: Phenol/Acetone. IHS Markit, PEP Rev. 2020–10. https://cdn.ihsmarkit.com/www/pdf/0720/RW2020-10_toc.pdf

-

Schutyser W, Renders T, den Bosch SV, Koelewijn S-F, Beckham GT, Sels BF. Chemicals from lignin: an interplay of lignocellulose fractionation, depolymerisation, and upgrading. Chem Soc Rev. 2018;47:852–908. https://doi.org/10.1039/C7CS00566K.

-

Liu X, Bouxin FP, Fan J, Budarin VL, Hu C, Clark JH. Recent advances in the catalytic depolymerization of lignin towards phenolic chemicals: a review. Chemsuschem. 2020;13:4296–317. https://doi.org/10.1002/cssc.202001213.

-

Li X, Xu Y, Alorku K, Wang J, Ma L. A review of lignin-first reductive catalytic fractionation of lignocellulose. Mol Catal. 2023;550: 113551. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcat.2023.113551.

-

Choi H, Alherech M, HeeJang J, Woodworth S, Ramirez K, Karp E, et al. Counter-current chromatography for lignin monomer–monomer and monomer–oligomer separations from reductive catalytic fractionation oil. Green Chem. 2024;26:5900–13. https://doi.org/10.1039/D4GC00765D.

-

Bomon J, Bal M, Achar TK, Sergeyev S, Wu X, Wambacq B, et al. Efficient demethylation of aromatic methyl ethers with HCl in water. Green Chem. 2021;23:1995–2009. https://doi.org/10.1039/D0GC04268D.

-

Skaali R, Devle H, Ebner K, Ekeberg D, Sørlie M. Determining monolignol oxifunctionalization by direct infusion electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Methods. 2024;16:2983–96. https://doi.org/10.1039/D4AY00403E.

-

Guo Y, Alvigini L, Trajkovic M, Alonso-Cotchico L, Monza E, Savino S, et al. Structure- and computational-aided engineering of an oxidase to produce isoeugenol from a lignin-derived compound. Nat Commun. 2022;13:7195. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-34912-3.

-

Hyldgaard M, Mygind T, Piotrowska R, Foss M, Meyer RL. Isoeugenol has a non-disruptive detergent-like mechanism of action. Front Microbiol. 2015. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2015.00754.

-

Api AM, Belsito D, Bhatia S, Bruze M, Calow P, Dagli ML, et al. RIFM fragrance ingredient safety assessment, isoeugenol, CAS Registry Number 97–54-1. Food Chem Toxicol. 2016;97:S49-56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fct.2015.12.021.

-

Blanksby SJ, Ellison GB. Bond dissociation energies of organic molecules. Acc Chem Res. 2003;36:255–63. https://doi.org/10.1021/ar020230d.

-

Dick AR, Sanford MS. Transition metal catalyzed oxidative functionalization of carbon–hydrogen bonds. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:2439–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tet.2005.11.027.

-

Shteinman AA. Activation and selective oxy-functionalization of alkanes with metal complexes: Shilov reaction and some new aspects. J Mol Catal A: Chem. 2017;426:305–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcata.2016.08.020.

-

Barranco S, Zhang J, López-Resano S, Casnati A, Pérez-Temprano MH. Transition metal-catalysed directed C-H functionalization with nucleophiles. Nat Synth. 2022;1:841–53. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44160-022-00180-8.

-

Cao M, Wang H, Hou F, Zhu Y, Liu Q, Tung C-H, et al. Catalytic enantioselective hydroxylation of tertiary propargylic C(sp3)–H bonds in acyclic systems: a kinetic resolution study. J Am Chem Soc. 2024;146:18396–406. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.4c03610.

-

Münch J, Püllmann P, Zhang W, Weissenborn MJ. Enzymatic hydroxylations of sp3-carbons. ACS Catal. 2021;11:9168–203. https://doi.org/10.1021/acscatal.1c00759.

-

Monterrey DT, Menés-Rubio A, Keser M, Gonzalez-Perez D, Alcalde M. Unspecific peroxygenases: the pot of gold at the end of the oxyfunctionalization rainbow? Curr Opin Green Sustain Chem. 2023;41: 100786. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogsc.2023.100786.

-

Grogan G. Hemoprotein catalyzed oxygenations: P450s, UPOs, and progress toward scalable reactions. JACS Au. 2021;1:1312–29. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacsau.1c00251.

-

Hofrichter M, Kellner H, Pecyna MJ, Ullrich R. Fungal unspecific peroxygenases: heme-thiolate proteins that combine peroxidase and cytochrome P450 properties. In: Hrycay EG, Bandiera SM, editors. Monooxygenase, Peroxidase and Peroxygenase Properties and Mechanisms of Cytochrome P450. Cham: Springer International Publishing. 2015;341–68. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-16009-2_13

-

Karich A, Kluge M, Ullrich R, Hofrichter M. Benzene oxygenation and oxidation by the peroxygenase of Agrocybe aegerita. AMB Expr. 2013;3:5. https://doi.org/10.1186/2191-0855-3-5.

-

Yan X, Zhang X, Li H, Deng D, Guo Z, Kang L, et al. Engineering of unspecific peroxygenases using a superfolder-green-fluorescent-protein-mediated secretion system in Escherichia coli. JACS Au. 2024;4:1654–63. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacsau.4c00129.

-

Brasselet H, Schmitz F, Koschorreck K, Urlacher VB, Hollmann F, Hilberath T. Selective peroxygenase-catalysed oxidation of phenols to hydroquinones. Adv Synth Catal. 2024;366:4430. https://doi.org/10.1002/adsc.202400872.

-

Lucarini M, Pedrielli P, Pedulli GF, Cabiddu S, Fattuoni C. Bond dissociation energies of O−H bonds in substituted phenols from equilibration studies. J Org Chem. 1996;61:9259–63. https://doi.org/10.1021/jo961039i.

-

Erickson E, Bleem A, Kuatsjah E, Werner AZ, DuBois JL, McGeehan JE, et al. Critical enzyme reactions in aromatic catabolism for microbial lignin conversion. Nat Catal. 2022;5:86–98. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41929-022-00747-w.

-

Hofrichter M, Kellner H, Herzog R, Karich A, Kiebist J, Scheibner K, et al. Peroxide-mediated oxygenation of organic compounds by fungal peroxygenases. Antioxidants. 2022;11:163. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox11010163.

-

Varadachari C, Ghosh K. On humus formation. Plant Soil. 1984;77:305–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02182933.

-

Kinne M, Poraj-Kobielska M, Ullrich R, Nousiainen P, Sipilä J, Scheibner K, et al. Oxidative cleavage of non-phenolic β-O-4 lignin model dimers by an extracellular aromatic peroxygenase. Holzforsch. 2011;65:673–9. https://doi.org/10.1515/hf.2011.057.

-

Fu L, Niu B, Zhu Z, Wu S, Li W. CD-HIT: accelerated for clustering the next-generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:3150–2. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bts565.

-

Teufel F, Almagro Armenteros JJ, Johansen AR, Gíslason MH, Pihl SI, Tsirigos KD, et al. SignalP 6.0 predicts all five types of signal peptides using protein language models. Nat Biotechnol. 2022;40:1023–5. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-021-01156-3.

-

Katoh K, Misawa K, Kuma K, Miyata T. MAFFT: a novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:3059–66. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkf436.

-

Capella-Gutiérrez S, Silla-Martínez JM, Gabaldón T. trimAl: a tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1972–3. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp348.

-

Minh BQ, Schmidt HA, Chernomor O, Schrempf D, Woodhams MD, von Haeseler A, et al. IQ-TREE 2: New models and efficient methods for phylogenetic inference in the genomic era. Mol Biol Evol. 2020;37:1530–4. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msaa015.

-

Kalyaanamoorthy S, Minh BQ, Wong TKF, von Haeseler A, Jermiin LS. ModelFinder: fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat Methods. 2017;14:587–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.4285.

-

Hoang DT, Chernomor O, von Haeseler A, Minh BQ, Vinh LS. UFBoot2: improving the ultrafast bootstrap approximation. Mol Biol Evol. 2018;35:518–22. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msx281.

-

Caplan S, Kurjan J. Role of alpha-factor and the MF alpha 1 alpha-factor precursor in mating in yeast. Genetics. 1991;127:299–307. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/127.2.299.

-

Vogl T, Sturmberger L, Kickenweiz T, Wasmayer R, Schmid C, Hatzl A-M, et al. A toolbox of diverse promoters related to methanol utilization: functionally verified parts for heterologous pathway expression in Pichia pastoris. ACS Synth Biol. 2016;5:172–86. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssynbio.5b00199.

-

Gibson DG, Young L, Chuang R-Y, Venter JC, Hutchison CA, Smith HO. Enzymatic assembly of DNA molecules up to several hundred kilobases. Nat Methods. 2009;6:343–5. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.1318.

-

Weis R, Luiten R, Skranc W, Schwab H, Wubbolts M, Glieder A. Reliable high-throughput screening with Pichia pastoris by limiting yeast cell death phenomena. FEMS Yeast Res. 2004;5:179–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.femsyr.2004.06.016.

-

Linde D, Santillana E, Fernández-Fueyo E, González-Benjumea A, Carro J, Gutiérrez A, et al. Structural characterization of two short unspecific peroxygenases: two different dimeric arrangements. Antioxidants. 2022;11:891. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox11050891.

-

Nimz HH, Turznik G. Reactions of lignin with singlet oxygen. I. Oxidation of monomeric and dimeric model compounds with sodium hypochlorite-hydrogen peroxide. Cellul Chem Technol. 1980;14:727–42.

-

Abramson J, Adler J, Dunger J, Evans R, Green T, Pritzel A, et al. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature. 2024;630:493–500. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07487-w.

-

Deng D, Jiang Z, Kang L, Liao L, Zhang X, Qiao Y, et al. An efficient catalytic route in haem peroxygenases mediated by O2/small-molecule reductant pairs for sustainable applications. Nat Catal. 2025;8:20–32. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41929-024-01281-7.

-

Kinne M, Poraj-Kobielska M, Ralph SA, Ullrich R, Hofrichter M, Hammel KE. Oxidative cleavage of diverse ethers by an extracellular fungal peroxygenase. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:29343. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M109.040857.

-

Li C, Hoffman MZ. One-electron redox potentials of phenols in aqueous solution. J Phys Chem B. 1999;103:6653–6. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp983819w.

-

Ashworth MA, Bombino E, de Jong RM, Wijma HJ, Janssen DB, McLean KJ, et al. Computation-aided engineering of cytochrome P450 for the production of pravastatin. ACS Catal. 2022;12:15028–44. https://doi.org/10.1021/acscatal.2c03974.

-

Fang Y, Liu L, Feng Y, Li X-S, Guo Q-X. Effects of hydrogen bonding to amines on the phenol/phenoxyl radical oxidation. J Phys Chem A. 2002;106:4669–78. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp014425z.

-

Rhile IJ, Markle TF, Nagao H, DiPasquale AG, Lam OP, Lockwood MA, et al. Concerted proton-electron transfer in the oxidation of hydrogen-bonded phenols. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:6075–88. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja054167.

-

Henriksen A, Smith AT, Gajhede M. The structures of the horseradish peroxidase c-ferulic acid complex and the ternary complex with cyanide suggest how peroxidases oxidize small phenolic substrates. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:35005–11. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.274.49.35005.

-

Molina-Espeja P, Beltran-Nogal A, Alfuzzi MA, Guallar V, Alcalde M. Mapping potential determinants of peroxidative activity in an evolved fungal peroxygenase from Agrocybe aegerita. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2021;9: 741282. https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2021.741282.

-

Bremus C, Herrmann U, Bringer-Meyer S, Sahm H. The use of microorganisms in L-ascorbic acid production. J Biotechnol. 2006;124:196–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiotec.2006.01.010.

-

Susa F, Pisano R. Advances in ascorbic acid (vitamin C) manufacturing: green extraction techniques from natural sources. Processes. 2023;11:3167. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr11113167.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge Hanne Devle (KBM, NMBU) for her technical support in establishing the GC-MS method. We also thank the NMR Lab (NMBU) and the Norwegian NMR Platform (NNP) for their support and technical assistance.

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Barros-Reguera, M., Lopez-Tavera, E., Schröder, G.C. et al. Structure–function relationships in unspecific peroxygenases revealed by a comparative study of their action on the phenolic lignin monomer 4-propylguaiacol. Biotechnol. Biofuels Bioprod. 18, 83 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13068-025-02675-w

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13068-025-02675-w