Introduction

In conventional drug delivery modalities, such as oral tablets, capsules, and intravenous injections, therapeutic agents are typically distributed systemically throughout the body1. For instance, following intravenous administration of cisplatin, a widely used chemotherapy drug for cancer treatment, only approximately 0.5–1% of the injected dose accumulates in the tumor tissues, the remainder is rapidly distributed to off-target organs, such as the liver, kidney, and lung, resulting in the widespread systemic toxicity2.

In recent years, nanotechnology-based targeted drug delivery systems have been extensively developed with the aim of enhancing drug accumulation and controlled drug release at pathological sites, thereby enabling precision therapy3,4,5,6. Numerous researches confirmed that nanoparticles (NPs) have unique advantages in loading drugs, penetrating biological interfaces, targeting focus, and responding the microenvironment to achieve controlled drug release, showing potential application prospects in drug delivery7,8,9. In these studies, a variety of materials were employed in the construction of NP carriers10,11. Unfortunately, many commonly studied nanoparticle carriers, particularly non-biodegradable inorganic nanomaterials such as AuNPs, SiO2, carbon nanotubes, and metal oxides, have been reported to induce acute or long-term adverse effects12. These include oxidative stress, genotoxicity, chronic inflammation, hepatic and renal accumulation, and impaired tissue regeneration, largely due to their poor biodegradability and persistent retention in vivo. As a result, only a small number of nanoparticle carriers have received FDA approval for clinical use, most notably albumin nanoparticles (e.g., Abraxane®), lipid nanoparticles (e.g., Comirnaty®), and PLGA-based systems13,14.

Protein NPs (PNPs), as a class of naturally derived materials, have excellent biocompatibility and biodegradability, have been demonstrated distinct advantages in cancer therapy, chronic disease management, and tissue reconstruction15,16,17. Commonly utilized PNPs carriers include silk fibroin (SF), albumin, gelatin, and casein, which are widely studied due to their natural abundance, excellent biocompatibility, and high drug-loading capacities18. Among these, clinically approved protein-based nanoparticles are predominantly derived from endogenous human proteins, with albumin nanoparticles such as Abraxane® representing the most successful example19. The clinical translation has been facilitated by intrinsic biocompatibility, negligible immunogenicity, well-defined molecular structure, and mature large-scale manufacturing platforms. In contrast, although SF was an FDA-approved biopolymer that has been successfully applied in various clinical contexts, such as surgical suture, tissue regeneration scaffold, due to biocompatibility, tunable β-sheet, and versatile drug-loading capabilities20,21,22, silk fibroin nanoparticles (SFNPs) remain at the preclinical stage. The major barriers include batch-to-batch variations arising from degumming and regeneration processes, potential immunogenicity associated with sericin residues, variable degradation kinetics, and the absence of established GMP-compliant manufacturing strategies23.

SFNPs can be prepared by simple methods, such as desolvation, and exhibit excellent biocompatibility and low immunogenicity, as well as diversified drug loading capabilities, excellent mucosal adhesion, and tissue penetration24,25. Compared with conventional oral small-molecule formulations that undergo extensive first-pass metabolism, intravenous injections that result in rapid systemic distribution and off-target exposure, and topical preparations with limited tissue penetration, SFNPs can improve drug localization at pathological sites by enhancing drug stability, prolonging circulation, and enabling controlled or stimuli-responsive release26. Furthermore, SFNPs constitute an advanced drug delivery platform that enables precise and controllable therapeutic release owing to their targeting capability and stimuli-responsiveness (Scheme 1). These features substantially enhance therapeutic outcomes while minimizing systemic toxicity.

Extraction and structural characterization of SF

Silk is a natural protein produced by a variety of insects, exhibiting remarkable diversity in sequence, structure, and physicochemical properties27. SF from the Bombyx mori silkworm cocoons and spidroins from the spider silks are the most extensively studied representatives. Spidroins possess outstanding mechanical properties but suffer from significant limitations, including extremely low natural yield, difficulties in farming spiders, complex protein assembly pathways, and challenges in recombinant large-scale production28. By contrast, SF is more readily obtainable due to the ease of silkworm domestication and large-scale cultivation, making it a more practical and sustainable source for biomedical applications18.

SF extraction

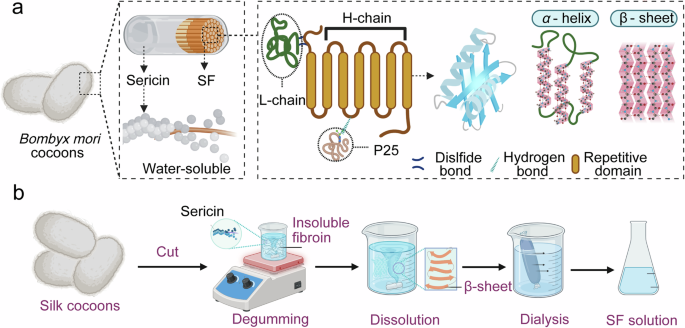

SF can be chemically extracted from silkworm cocoons, which consist of a fibroin core (approximately 75% w/w) and sericin coating (approximately 25% w/w), as illustrated in Fig. 1a. Sericin is a water-soluble, globular glycoprotein capable of eliciting immune responses5,27,29. Specifically, SF extraction typically involves four major steps: (1) degumming to remove sericin, (2) dissolution of the fibroin fibers, (3) dialysis to remove salts, and (4) lyophilization to remove water (Fig. 1b). Additionally, correlational research described how to get SF out of the silk gland by dissolving in anionic surfactants, such as lithium dodecyl sulfate and sodium dodecyl sulfate30. Currently, commonly used degumming methods include alkaline treatment, enzymatic digestion, and neutral solvent extraction. Alkaline degumming using sodium carbonate (Na2CO3) is the most widely employed method in laboratory and industrial due to the low cost and high efficiency31. The choice of degumming method has to be carefully tailored to preserve silk integrity and specific biological performance requirements. Following degumming, SF can be dissolved in a variety of solvents, such as lithium bromide (LiBr), calcium chloride (CaCl₂), hexafluoroisopropanol (HFIP), and trifluoroacetic acid (TFA)32,33. These solvents primarily function by interacting with the polar functional groups within SF and disrupting its β-sheet structures and hydrogen bonding networks, which enable effective solubilization of SF. It should be noted that the molecular chain of SF has been broken into molecular segments with a continuous molecular weight distribution after the degumming and dissolution34. Dissolved SF solution (contains salt, pigment and other impurities) can’t be used directly, must go through a series of purification and post-treatment steps. After being encapsulated into the dialysis bag with molecular weight cut-off (MWCO) of 8-14 kDa, small molecular impurities (salt, solvent ions) diffuse into the water outside the bag, while large molecular SF are retained in the bag. After dialysis, the aqueous solution is difficult to store and inconvenient to transport. Freeze-drying removes moisture from the SF solution to obtain porous sponge-like solid materials1, which are easy to store and transport for a long time, and can be used for subsequent re-dissolution or direct use as scaffold materials.

a Schematic diagram of SF chain stacking, α-helix, β-sheet and the two main crystalline units formed by the folding model. b Extraction process of SF.

Molecular structure of SF

SF is considered as an ideal material for the fabrication of PNPs due to the excellent biocompatibility, biodegradability, and low cost35. Furthermore, structural stability, processability, and tunable crystallinity of SF enhance its versatility for nanoparticle engineering. Exploring the structural of SF is fundamental to modify and realize functionality for specific application scenarios.

Primary structure of SF

SF consists of 18 kinds of amino acids, and its primary structure refers to the linear amino acid sequence with approximately 5000–5500 amino acids, which is highly repetitive and dominated by a few simple amino acids, such as glycine (Gly, ~43%), alanine (Ala, ~29%), and serine (Ser, ~12%)36,37. The recurrent sequences of glycine, alanine, and serine amino acids facilitate the tight packing of molecular chains, promoting the formation of well-ordered β-sheet structures that underpin the exceptional mechanical properties of SF38. SF is composed of two basic subunits, the heavy chain (H-chain), the light chain (L-chain), which are covalently linked through disulfide bonds to form H-L complexes, which binds to P25 through hydrophobic interaction with the ratio of the three is about 6:6:139. The heavy chain (~390 kDa) and light chain (~26 kDa) are covalently linked via disulfide bonds, forming a stable complex that adopts a highly ordered β-sheet conformation40 (Fig. 1a).

Functional modification can be easily carried out to endow SF with more biological activity for biomedical field owing to the numerous reactive amino acid residues, such as tyrosine, serine, and aspartic acid41. For instance, by taking advantage of the relatively high number of tyrosine residues, a tyrosine-specific diazonium coupling chemistry can be used to engineer the protein surface chemistry and hydrophilicity for proper cell adhesion and proliferation in cell culture scaffolds38. Sofia et al. reported that the covalent decoration of SF with integrin recognition sequences (RGD) and parathyroid hormone improved the cyto-compatibility42. Moreover, studies have demonstrated that SFNPs elicit minimal inflammatory responses, do not interfere with normal tissue regeneration, and exhibit excellent tolerance in both systemic and localized administrations43,44,45. Fernández-García and colleagues implanted SF hydrogel directly into the mouse brains and observed that inflammation and cell death at the implantation sites were transient46. Meanwhile, the mice exhibited no significant cognitive or sensorimotor impairments, suggesting that SF was a well-tolerated and safe biomaterial for neural applications.

Secondary structure of SF

SF exhibits two predominant crystalline polymorphs (Silk I and Silk II). Silk I is recognized as a metastable conformation, primarily comprising random coil, α-helice, and amorphous region47,48. In contrast, Silk II represents the thermodynamically stable structure49, characterized by highly ordered antiparallel β-sheet domains that endow the material with exceptional mechanical strength and structural integrity47. The β-sheets within SF can be modulated through environmental parameters, such as pH value, ionic strength, temperature, concentration, and polar solvents like ethanol or methanol, enabling tunable physicochemical and biological properties. Owing to its unique β-sheet architecture, combined with remarkable biocompatibility, mechanical robustness, and controllable biodegradability, SF was fabricated into different forms for biomedical applications, such as suture, biosensor, tissue scaffolds, and drug delivery vehicles50.

Synthesis and modification strategies for SFNPs

Desirable nanoscale drug delivery systems have to possess well-controlled particle size, uniform size distribution, structural stability, bio-functionality, and strong encapsulation capacity for therapeutic agents or bioactive molecules18. Commonly used techniques for SFNP preparation include desolvation, electro-spraying, emulsification, and microfluidic system1,32 (Fig. 2a–d). Each technique yields SFNPs with distinct drug-loading mechanisms, which in turn influence the encapsulation efficiency, release kinetic, and therapeutic performance of the loaded drugs. Therefore, the selection of an appropriate fabrication strategy is critical for tailoring SFNPs to specific drug-delivery applications. Table 1 lists the advantages, limitations, and main application directions of SFNPs preparation methods.

a Emulsion method, b electrospraying method, c desolvation, d microfluidic technology, and e synthesis and processing route of SFNPs.

Synthesis strategies

Desolvation

The desolvation method is one of the most widely employed techniques for fabricating SFNPs. The process involves the gradual addition of an aqueous SF solution into a non-solvent system, such as ethanol, acetone, or isopropanol. The desolvation triggers the formation of β-sheet structures, which facilitate protein aggregation and self-assembly into nanoscale particles24. The size and uniformity of SFNPs can be tuned by manipulating parameters, such as protein concentration, solvent addition rate, pH value, and temperature51,52. Higher pH values and lower protein concentrations generally yield smaller NPs. The non-solvent agent does not directly participate in the chemical synthesis, this technique facilitates the SF self-assembly process by reducing its solubility to promote condensation and nanostructure formation53. Mercedes et al. developed curcumin-loaded SFNPs with diameters ranging from 155 to 170 nm using desolvation methods52,54. Furthermore, Kundu et al. applied dimethyl sulfoxide as the desolvating agent to fabricate SFNPs55. The preparation involved sequential steps of protein isolation, desolvation, centrifugation, purification, sonication, filtration, and lyophilization1. The resulting NPs were stable, spherical, and negatively charged, with diameters ranging from ~150 to 170 nm. Structural analysis confirmed a predominant Silk II conformation, which contributed to their physicochemical stability24. Importantly, these SFNPs exhibited negligible cytotoxicity, underscoring their potential as safe drug carriers.

Emulsion method

Conventional polymeric NPs are typically fabricated via emulsion/solvent method, and these approaches can likewise be adapted for the preparation of protein-based NPs. The emulsification method relies on the formation of W/O or W/O/W emulsions to preparation NPs56. During the emulsification process, the protein concentration and the relative volume ratio of the aqueous and oil phase are critical parameters governing the successful fabrication of NPs. Under shear stress and interfacial tension, SF molecules undergo aggregation and solidification, ultimately forming NPs. The resulting SFNPs are typically stabilized by solvent evaporation or chemical crosslinking57,58. Myung et al. successfully prepared smooth SFNPs of 167–169 nm by adding SF solution to a mixture of surfactant and organic solvent to form a microemulsion. This technique generally produces particles with small diameters, smooth surface and spherical morphology. However, a major concern associated with this method is organic solvent residue, which may compromise the biocompatibility of the final product58. For this issue, Srisuwan et al. successfully prepared SFNPs by solvent evaporation of water-in-oil emulsions without any surfactants. The SF solution was mixed with paraffin to form water-in-oil emulsions, and heated to evaporate water to produce particles57. Therefore, efforts should be made to minimize the use of organic solvents and reduce solvent retention in SFNPs during fabrication.

Electro-spraying method

Electro-spraying has emerged as a promising and increasingly popular technique that utilizes high-voltage electrostatic forces to generate NPs from polymer solutions for the fabrication of protein-based particles in the submicron to nanoscale ranges59. When a strong electric field is applied, a Taylor cone forms at the tip of the capillary nozzle, and the solution is atomized into charged microdroplets, which undergo solvent evaporation and subsequently solidify into NPs. This method has been widely applied to the controlled fabrication of natural polymer-based nanomaterials due to the advantages of simple operation, uniform particle size, adjustable processing parameters, and compatibility with various drug payloads60,61. Jing et al. successfully fabricated cisplatin (CDDP)-loaded SFNPs with an average diameter of 59 nm using the electro-spraying technique without any organic solvents62. This method preserved the antitumor activity of CDDP while minimizing adverse effects on the healthy tissues, enhancing the therapeutic index of the chemotherapeutic agents. Despite its high precision in particle control and tunable parameters at the laboratory scale, electro-spraying faces challenges in terms of solvent selection, production yield, structural control, and scalability for industrial applications. These limitations may be addressed through strategies, such as green solvent systems, multi-nozzle configurations, and integrated post-processing techniques. Looking ahead, electro-spraying offers great potential for advancing drug delivery systems and precision medicine, especially when synergistically integrated with other fabrication technologies.

Microfluidic technology

As an emerging fabrication strategy, microfluidic platforms enable the precise control of shear rate and microscale mixing environments, allowing for rapid mixing, nucleation, and growth of SFNPs through controlled interactions between SF solution and anti-solvent16,63. This technique offers several pivotal advantages, including narrow size distribution, high structural uniformity, and continuous production capability. Different SFNPs fabrication techniques exhibit distinct characteristics in terms of particle size control, drug loading capacity, aqueous stability, and surface functionalization potential. Stable, controlled, and uniform formation of PNPs is critical to the successful delivery of cargo into target cells. Utilizing naturally occurring eddy currents within droplets can prevent aggregation of nucleated NPs, resulting in systematic control of particle size and monodispersity64. Mansor et al. prepared SFNPs by microfluidic-assisted desolvation using a cyclone mixer16. The resulting SFNPs exhibited a uniform size distribution (<200 nm, polydispersity index (PDI) < 0.20) and maintained size stability for up to 30 d. The encapsulation efficiency for curcumin and 5-fluorouracil was 37% and 82%, respectively, and the release ratio within 72 h for curcumin and 5-fluorouracil was 50% and 70%, respectively. These results indicate the potential of microfluidic system in the production of SFNPs and their subsequent application in drug delivery.

Compared with traditional batch methods (such as bottom-up assembly, desolvation, electrospray, etc.), microfluidic technology provides a revolutionary solution for the development of green, scalable and controllable SFNPs synthesis processes due to its precise fluid manipulation, efficient mass and excellent scalability65,66. Microfluidics technology controls the flow rate and proportion of fibroin solution, precipitant (such as polyethylene glycol (PEG), ethanol) and other fluids with micron precision from μL/min to mL/min through syringpumps or pressure controllers, realizing precise regulation of mixing time (millisecond level) and mixing degree23,67.

In addition, the core amplification strategy of microfluidic is not to increase the size of a single channel (which will destroy its hydrodynamic characteristics), but to parallelize. Integrating thousands of micromixing units (such as T-junctions, chaotic mixers, droplet generators) on the same chip or module can achieve linear amplification from ml/h to L/h or even higher, and the product properties are consistent with the results of a single channel in the laboratory, perfectly overcoming the amplification effect68,69.

The emphasis on green and scalable production lies in the choice of precipitant. Preferably, aqueous precipitants with good biocompatibility, recyclability or easy removal should be selected, as they represent the first choice for environmentally friendly process23,70. In terms of materials and manufacturing process, thermoplastic polymers with good solvent resistance are used to chip production, which is advantageous for reducing costs, conducive to disposable or clean, in line with GMP requirements. With respect to process integration, microfluidic chips can be coupled with online purification techniques (such as dialysis, tangential flow filtration), online characterization methods (dynamic light scattering), and automatic collection modules to build an end-to-end continuous production system, thereby minimizing manual intervention and improving overall efficiency and consistency71.

Looking ahead, synthesis strategies for SFNPs have focused on the development of green, scalable, and controllable processes. Specifically, future efforts should prioritize the development of fully aqueous, solvent-free, and universal microfluidic processes, thereby minimizing environmental impact and improving process robustness. In parallel, the design of low-cost, mass-manufacturable parallel microreactor modules is essential to enable large-scale production. Moreover, deeper integration of process analysis technology (PAT) will allow real-time, online monitoring and feedback control of product quality34. Through continuous innovation, microfluidic-assisted continuous flow synthesis is expected to become the gold standard for the production of high-performance, clinical-grade SFNPs (Fig. 2e).

Modification of SFNPs

Selective chemistry modification can enhance or modulate SF properties, such as mechanics, biodegradability, processability, and biological interactions, to address the challenges of medically relevant materials, including SFNPs, hydrogels, films, sponges, and fibers72,73. To overcome drug delivery limitations and improve the biomedical applicability of SFNPs, various modification strategies are employed to introduce reactive moieties or bioactive ligands74.

Chemical modification of functional groups

Chemical modification of SFNPs is primarily accomplished by attacking specific functional side chain groups on amino acids, including hydroxyl groups on serine, threonine, and tyrosine; -NH2 on lysine; -COOH on aspartic acid and glutamic acid; and sulfhydryl groups on cysteine75,76. Typical modification strategies of hydroxyl groups include the esterification, carboxylation, or etherification to tune hydrophilicity and degradation profiles. Additionally, the phosphorylation or sulfation of hydroxyl groups not only can introduce charged groups to enhance cell adhesion, but also bring in stimulus-responsive groups to optimize drug release profiles73. The phenolic hydroxyl group of tyrosine is particularly reactive and widely exploited for enzymatic crosslinking, chemical modification, and diazonium coupling73. For instance, horseradish peroxidase/H2O2-mediated reactions enabled the construction of stimuli-responsive SFNPs77. These hydroxyl-targeted modifications collectively expand the structural tunability and biomedical functionality of SFNPs, supporting their application in drug delivery, tissue engineering, and regenerative medicine. The carbodiimide coupling can form amide links between -COOH and -NH2, which was often used to incorporate SF with other kinds of biological molecules, including vitamin, peptide, protein, enzyme, and polysaccharide73. Such modifications significantly enhance the binding affinity of SF for therapeutic agents and impart targeting capability, immunomodulatory function, and prolonged circulation time to SFNPs, thereby improving the biomedical performance of SFNPs.

Complexation with other polymers

Preparation of SF-polymer composite is an effective strategy to enhance the physicochemical properties of SFNPs by covalently attaching or physically mixing polymers, such as PLA, PCL, PEG, and polyvinyl alcohol (PVA)78,79,80. Cao et al. prepared PVA/SFNPs with core–shell structure and pH-responsiveness through one-step electro-spraying method, and the drug encapsulation efficiency for PVA/SFNPs was larger than 90%81. This modification improves the controllability of drug release rate by alternating PVA/SF ratios, making it more suitable for long-term drug delivery application. John et al. covalently modified SFNPs with cyanuric chloride-activated PEG. The PEGylated SFNPs exhibited better colloidal stability, degradation characteristics, and controlled drug release profiles, and illustrating that the PEGylation reduced the inflammatory and metabolic responses of SFNPs initiated by macrophages10. Such modifications enhance the therapeutic precision and pharmacokinetic performance of SFNP-based drug delivery systems, making them highly suitable for tumor targeting, immune modulation, and long-acting therapies. The development route of SFNPs clearly reflects the evolution process from basic preparation method exploration, precise controllable processing, functionalization and application expansion, and finally to intelligent and clinical industrialization.

Properties of SFNPs

Physicochemical properties of SFNPs, including diameter, morphology, surface charge, secondary structure, and stimuli-responsiveness play a pivotal role in colloidal stability, biocompatibility, drug loading efficiency, and in vivo performance82,83. Therefore, a systematic characterization for SFNPs is essential for rational design of high-performance nanocarriers tailored for specific biomedical applications.

Physicochemical properties of SFNPs

Particle size critically affects the in vivo biodistribution, tissue penetration, cellular uptake, and endocytic pathway of NPs84,85. For SFNPs, an ideal particle size typically ranges between 50 and 300 nm (Fig. 3b), and PDI less than 0.3 indicates a narrow size distribution and uniform particle population, which are essential for reproducible biological behavior and predictable pharmacokinetics. Furthermore, the surface charge of SFNPs significantly influences their colloidal stability, interaction with biological membranes, and systemic circulation time86. NPs with zeta potential greater than ±30 mV are generally considered to possess high colloidal stability due to strong electrostatic repulsion, which minimizes aggregation in physiological conditions82,87. By modifying SFNPs, the surface charge can be changed actively. For example, coating or grafting with cationic polymers (chitosan and polyethyleneimine (PEI)) can change the Zeta potential of SFNPs from negative to positive, which not only improves stability, but also changes their interaction with negatively charged cell membranes and promotes cell uptake88,89. Wang et al. engineered core-shell structured SFNPs by coating the NPs with four distinct cationic polymers (glycol chitosan, N, N, N-trimethyl chitosan, PEI, and PEGylated PEI) via electrostatic interactions82. The SFNPs exhibited excellent colloidal stability in biological media, highlighting their potential as carriers for anticancer drug delivery systems owing to the ideal colloidal stability in biological medium.

a Preparation and structure of representative Res-BmNPs. b SEM images of SFNPs. Scale bar = 200 nm. c SFNPs release curcumin in response to pH, ROS, and GSH stimuli. d Principles of pH, ROS and GSH stimulating drug release, as represented by typical studies. Part a–d reprinted with permission from ref. 94, Elsevier.

Stimuli-responsiveness of SFNPs

Precise spatial and temporal control over drug release from delivery carriers is critical for achieving therapeutic efficacy and minimizing side effect. The design and modification of multi-responsive NPs offer a promising strategy for achieving site-specific and stimuli-triggered drug release within diseased tissues90,91,92,93. Unmodified SFNPs naturally exhibit certain environmental stimulus responsive characteristics due to the unique molecular structure of SF. Kaplan et al. reported that SFNPs precipitated by acetone exhibited pronounced pH-responsive drug release behavior (pH value from 7.4 to 4.5)11. Furthermore, the studies of Ma et al. showed that unmodified SFNPs also had reactive oxygen species (ROS), acidic, and glutathione (GSH) responsiveness (Fig.3c–d). This phenomenon can be explained by that hydrogen ions, ROS, and GSH induced deconstruction of β-sheet structures and disulfide bonds in SFNPs, thereby loosening their structure and accelerating drug release94. Meanwhile, Serban et al. developed an SFNPs via carbodiimide-mediated conjugation of SF with poly-L-lysine hydrobromide and sodium polyglutamate. These NPs can encapsulate doxorubicin (DOX), a hydrophilic anti-cancer drug, providing responsive drug release behavior under acidic conditions owing to the markedly weakened electrostatic interactions between SF matrix and DOX molecules79. These findings suggest that SFNPs can serve as effective pH-sensitive carriers, enabling site-specific drug delivery in acidic tumor microenvironments. Additionally, related research confirmed that SFNPs exhibited enzyme-responsiveness. Totten et al. developed PEG-functionalized SFNPs and investigated the DOX release profiles under acidic buffer conditions with or without lysosomal enzymes. The experimental data demonstrated that the drug release profiles of PEGylated SFNPs were notably accelerated in an acidic environment with lysosomal enzymes, mimicking the intracellular environment of endo-lysosomes. This enzymatic and pH-responsive drug release highlights the potential of PEG-SFNPs for efficient intracellular drug delivery, enhancing therapeutic efficacy while minimizing off-target cytotoxicity6.

To enhance diseased site-specific drug release, reactive chemical groups can be covalently incorporated into SF backbone7,79. For instance, the introduction of representative cleavable linkages, including diselenide, disulfide, and boronate ester bonds, reinforced the drug release of SFNPs in oxidative tumorous microenvironments owing to the responsive cleavage of these linkages. Similarly, pH-sensitive linkers, such as hydrazone and ester bonds, also can be used to enhance the site-specific drug release for SFNPs. More importantly, these bonds are stable under physiological conditions, minimizing the adverse reaction to healthy tissues and promoting controlled drug release at diseased sites.

Collectively, the synthetic processing and chemical modification play a pivotal role in determining the size, stability, and drug-loading efficiency of SFNPs. More importantly, these upstream modifications directly influence the in vivo site-targeting efficiency, payload release profile, and therapeutic performance of SFNPs. By strategically tuning parameters, such as molecular weight, surface functionalization, and stimuli responsiveness, SFNPs can be efficiently engineered to meet the demands of complex biomedical applications.

Degradation behavior of SFNPs

Silk protein is considered biodegradable because it is sensitive to proteases such as proteinase K, proteinase XIV, collagenase, and α-chytridase, as well as enzyme-catalyzed hydrolysis reactions95. The degradation behavior of SFNPs plays a pivotal role in pharmacokinetics, therapeutic duration, and biosafety. SFNPs with higher β-sheet exhibit slower degradation and prolonged drug retention, whereas amorphous or low-crystallinity particles undergo faster enzymatic hydrolysis, favoring rapid clearance and transient therapeutic96. Importantly, the degradation byproducts, peptides and amino acids such as glycine, alanine, and serine, are biocompatible and non-immunogenic, minimizing systemic toxicity95. SFNPs of oral administration undergo a distinct, multi-stage degradation process driven by the complex gastrointestinal. Upon entering the stomach, SFNPs encounter strongly gastric acid, which induces partial protonation of -NH2 and -COOH, leading to hydration, chain swelling, and disruption of amorphous domains97.

However, β-sheet crystal region can significantly enhance its structural stability in gastric acid environment. In addition, related studies show that PEG-modified SFNPs can significantly change degradation behavior95. As SFNPs transit to the small intestine, weakening electrostatic interactions within the protein nanostructures and promoting controlled protein lattice loosening. Concurrently, digestive enzymes, chymotrypsin, elastase, and intestinal proteases, selectively cleave accessible peptide linkage in the amorphous regions6,95. This results in surface erosion dominating the SFNPs biodegradation, while β-sheet nanocrystals degrade more slowly, enabling sustained drug release. In the colon, SFNPs encounter reduced oxygen tension, abundant microbial proteases, and higher viscosity, which collectively accelerate degradation and facilitate site-specific payload liberation, particularly beneficial for IBD therapy94.

The degradation of SFNPs is predominantly enzyme-mediated and strongly depends on enzyme type, secondary structure, and surface modifications. From a pharmacokinetic perspective, such surface modifications can prolong systemic circulation, enhance stability under oral administration conditions, and improve the potential for penetration and retention (EPR)-mediated tumor accumulation98. However, the limits of long-term biodistribution, metabolic and clearance pathways, and potential chronic toxicity or immunological responses. These gaps continue to pose significant barriers to clinical translation.

The EPR of SFNPs

NPs circulate in the bloodstream, ooze out at tumor due to vascular leakage, and accumulate due to impaired lymphatic drainage. This phenomenon is often referred to as the EPR effect99. The EPR effect represents a fundamental mechanism by which SFNPs achieve passive accumulation within tumor. Recent studies on NPs delivery mechanisms have clarified that tumor accumulation of nanoscale carriers is governed by both the classical EPR effect and the more recently proposed active transport and retention (ATR) processes100. SFNPs, typically sized within 50–200 nm and exhibiting hydrophilic surfaces, fit well within the element known to favor EPR-mediated passive tumor accumulation. Moreover, SFNPs protein-based nanostructure suggests a tendency to follow passive rather than active endothelial transcytosis routes101. Overall, available evidence indicates that SFNPs possess physicochemical features favorable for EPR accumulation, while their proteinaceous softness may bias them toward passive over active transport. But, systematic studies directly quantifying EPR versus ATR contributions for SFNPs remain lacking, and future work is needed to map tumor-specific transport pathways, patient-to-patient variability, and microenvironmental factors that regulate SFNP deposition.

In addition, combining the EPR-driven passive targeting of SFNPs with active ligand modification (e.g., folic acid, RGD peptide, or antibody conjugation) can synergistically enhance tumor specificity and cellular uptake102. Collectively, these findings highlight the intrinsic compatibility of SFNPs with EPR-mediated tumor targeting and underscore as biocompatible nanocarriers for precision oncology applications.

Interaction of SFNPs and cells

SFNPs enter cells mainly through endocytosis, which depends on the size, surface charge and degree of modification of nanoparticles86,103. After internalization, they form endosomes, which are degraded by acidic environment and enzyme action, thus releasing the loaded substances (such as drugs and genes). Some undegraded particles or released molecules enter the cytoplasm to play role. Eventually, SFNPs can be progressively degraded by intracellular proteases such as cathepsin to amino acids that can be reused or excreted and are highly biocompatible95,104. In short, SFNPs complete the absorption cycle in vivo through four pathways: adsorption and adhesion, internalization, intracellular transport and fate, and biodegradation105.

The interaction between SFNPs and cells/tissues is a complex process with many steps and factors. The key determinants can be summarized as physicochemical properties of SFNPs, cell type characteristics and microenvironmental. There are significant differences in membrane receptor expression, metabolic activity and endocytosis mechanism among different cells55. At the cellular level, SFNPs regulate adhesion, uptake, migration, and fate decisions through a combination of surface chemistry, nanoscale topography, and secondary structure. The abundance of polar functional groups and tunable β-sheet content enables SFNPs to modulate integrin-mediated signaling pathways, thereby promoting epithelial and fibroblast adhesion and migration, which is essential for tissue regeneration and wound healing105. Importantly, SFNPs generally exhibit low immunogenicity and can actively shape immune responses. Wong et al. found that degradation products of SF scaffolds polarized THP-1-derived macrophages from a pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype to an anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype106. This immunomodulatory behavior is especially advantageous in inflamed or damaged tissues, where controlled immune activation is required for effective repair. In addition, Cui et al. also showed that large nanoparticles failed to elicit a significant inflammatory response in macrophages. In contrast, ultra-small SFNPs (96 nm) were found to be phagocytized by macrophages and trigger a stronger immune response107. Totten et al. found that SFNPs induced a pro-inflammatory macrophage phenotype to confirm the conclusion10.

However, current research still faces challenges of in vitro to in vivo transformation, insufficient understanding of molecular mechanisms of interaction, and long-term biosafety to be evaluated. Future research needs to be validated in more complex physiological correlation models with advanced characterization techniques, so as to promote SFNPs from basic research to clinical transformation and open up new paths for precise drug delivery.

Biomedical applications

SFNPs, possess excellent biocompatibility, biodegradability, drug loading efficiency, can effectively encapsulate abundant agents, including small molecules, nucleic acids, and bioactive factors, which enable sustained and stimuli-responsive release under diverse physiological and pathological conditions55,108, making them an attractive platform for diverse biomedical applications, including drug delivery, immunoregulation, and tissue healing (Fig. 4).

a Surface-functionalized SFNPs for tumor therapy. b Tumor size and quantitative data for different treatments. Parts a, b reprinted with permission from ref. 92, Elsevier.

Cancer treatment

Cancer remains one of the leading causes of mortality worldwide. Conventional therapeutic modalities, such as surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy, have undoubtedly improved survival rates but are often limited by severe systemic toxicity, poor tumor selectivity, multidrug resistance, and rapid drug clearance109,110. In particular, many chemotherapeutic agents display unfavorable pharmacokinetics, with only a small fraction of the administered dose reaching the tumor site. At the same time, the majority distributes nonspecifically throughout the body, leading to dose-limiting side effects111,112. Moreover, the heterogeneity of tumor microenvironments, including hypoxia, acidic condition, and elevated ROS level, further complicates treatment outcomes113,114.

In cancer treatment, SFNPs have been employed to encapsulate a wide spectrum of therapeutic agents, including small-molecule chemotherapeutics (e.g., DOX, paclitaxel, and cisplatin), proteins, and nucleic acids (siRNA, mRNA, and plasmid). SFNPs protect the therapeutic payloads from premature degradation, enhance tumor accumulation via the enhanced EPR effect, and enable stimulus-responsive drug release in tumor microenvironments110. For example, pH-sensitive SFNPs accelerate drug release under acidic tumor conditions, while ROS or enzyme-responsive capacities further enhance drug release specificity and reduce systemic toxicity.

Moreover, active targeting strategies, such as conjugation with vitamin, peptide, and antibody, have been integrated into SFNPs to facilitate selective uptake by tumor cells overexpressing corresponding receptors4,73. Li et al. designed multi-responsive SFNPs co-loaded with chemotherapeutic agents (DOX and PX478) and hypoxia-inducible factor-1α inhibitor, while also functionalizing the surface with folic acid (FA) to achieve active tumor targeting102. The system was engineered to enable controlled release of PX478 in response to tumor microenvironment. In cytotoxicity assays against drug-resistant MCF-7/ADR breast cancer cells, the DOX-loaded SFNPs achieved a minimum effective dose of 1.0 μg/mL, which was approximately 26-fold lower than that of free DOX (25.6 μg/mL), indicating markedly enhanced therapeutic efficacy102. Sun et al. developed DOX-loaded SFNPs, which were further surface-functionalized via a covalent reaction between the -NH2 of SF and the -COOH of FA115. The resulting FA-DOX-NPs demonstrated selective internalization by tumor cells with overexpressed FA receptors and enabled controlled release of the encapsulated DOX. Notably, FA significantly enhanced the chemotherapeutic efficacy while simultaneously reducing the potential adverse effects associated with DOX administration115.

Furthermore, Shu et al. developed an inhalable hybrid liposome in which ferroptosis inducer and piperlongumine are coloaded into SFNPs to overcome the limitation of the poor therapeutic effect of single-drug ferroptosis. Compared to conventional intravenous formulations, the as-synthesized formulation FP@SLCDH increased pulmonary accumulation by 13.6-fold and lipid peroxidation products by 2.14-fold116. Gou et al. developed a self-assembled gelatin/silk cellulose complex (GSC) particle delivery system that rapidly immobilizes the drug within the GSC and compacts the GSC structure during desolvation, resulting in efficient drug loading and overall protection of the loaded drug. The size of the drug delivery system can be easily adjusted and exhibits excellent transmucosal penetration and lung retention117.

Previous studies have also demonstrated that SFNPs can be engineered into multifunctional platforms combining chemotherapy with photothermal or photodynamic therapy, achieving synergistic antitumor effects. For instance, Gou et al. developed a multifunctional nanotherapeutic platform by covalently grafting the organic anion-transporting polypeptide-targeted photosensitizer (N770) onto DOX-loaded SFNPs. The resulting N770-DOX@NPs exhibited strong responsiveness to acidic condition, H₂O₂, GSH, and elevated temperature, effectively mimicking the tumor microenvironment92 (Fig. 4a, b). This multi-stimulus responsive system enabled controlled and sustained drug release, leading to prolonged cytotoxic activity against cancer cells and enhanced therapeutic outcomes. Xiao and colleagues functionalized the surface of mesoporous silica NPs with Antheraea pernyi silk fibroin (ApSF). This dual-delivery system encapsulated DOX and the indocyanine derivative, a near-infrared (NIR) activated photosensitizer118. Upon NIR irradiation, the nanomotors exhibited deep tumor tissue penetration, mitochondrial targeting, and oxygen generation, enabling multimodal imaging-guided phototherapy118. This intelligent design highlighted the potential of SFNP platforms to integrate targeted delivery, responsive drug release, and real-time diagnostics, especially in solid tumor microenvironments where penetration depth remains a key therapeutic challenge.

Collectively, SFNPs represent a versatile and safe nanoplatform for oncology, offering improved drug bioavailability, reduced off-target toxicity, and enhanced therapeutic efficacy. Despite these advances, challenges remain in scaling up reproducible production and ensuring long-term safety. Future research is expected to focus on integrating SFNP-based systems into precision oncology and immunotherapy, accelerating their translation toward clinical application.

Inflammatory treatment

Inflammatory diseases, characterized by dysregulated immune responses and excessive production of pro-inflammatory mediators, are associated with chronic tissue damage and impaired organ function. Among them, intestinal inflammatory disorders, particularly inflammatory bowel diseases, represent major global health burdens119. Current therapies rely on corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, and biologics, which can alleviate symptoms but are often limited by poor mucosal targeting, systemic side effects, loss of therapeutic efficacy over time, and frequent relapses120,121. The complex intestinal microenvironment, featuring high enzymatic activity, fluctuating pH values, abundant ROS, and disrupted epithelial barriers, further hinders effective drug delivery and sustained therapeutic outcomes122.

SFNPs have excellent drug-carrying properties and inflammatory environmental responsiveness, enabling them to achieve precise drug release in complex pathological microenvironments. At the same time, SFNPs exhibit strong mucoadhesion and epithelial penetration capacity, enabling prolonged retention and local accumulation within the gastrointestinal tract. Furthermore, studies have demonstrated that modified SFNPs with hydrophilic stabilizers and positively charged coatings can cross challenging biological interfaces, such as skin, corneal epithelium, intestinal mucosa123, and even the blood brain barrier124,125, owing to the facilitated absorption by low density lipoprotein receptors, significantly enhancing drug bioavailability and therapeutic efficacy. Ma et al. reported a resveratrol-loaded SFNPs, which exhibited dual-targeting capabilities toward colonic epithelial cells and macrophages, as well as multi-stimuli responsiveness to oxidative and inflammatory signals94 (Fig. 5a). These SFNPs can effectively penetrate colonic mucus barrier to deliver resveratrol deeply, regulate inflammatory microenvironment, repair the disrupted epithelial barrier, and rebalance colon microbial community, and exert desirable therapeutic effect on inflammatory intestinal diseases. Liu et al. constructed a kind of epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG)-loaded SFNPs by simple microemulsion method and functionalized their surface with an antimicrobial peptide (CBF). They effectively treat inflammatory intestinal diseases by relieving oxidative stress, promoting epithelial migration, and regulating flora126 (Fig. 5b). These SFNPs have excellent penetration capacity in mucus-mimicking hydrogels due to the conjugation of CBF on the surface, which makes them zwitterionic and enables strong binding to water molecules through electrostatic interaction, thereby conferring resistance to non-specific interactions with mucus. These SFNPs delivered the anti-inflammatory EGCG efficiently, facilitated inflammation alleviation, epithelial barrier restoration, ROS scavenging, and gut microbiota modulation, indicating significant potential for gastrointestinal tissue repair and immune homeostasis.

Collectively, these features position SFNPs as a versatile and effective nanoplatform for the treatment of inflammatory intestinal diseases, with the potential to enhance local drug bioavailability, reduce systemic toxicity, and achieve durable remission.

Tissue engineering

SFNPs integrate drug delivery with structural support, thereby accelerating tissue regeneration and functional recovery in complex disease models. In bone and cartilage repair, modified SFNPs have been incorporated into composite scaffolds with hydroxyapatite and collagen, serving both as structural reinforcers and as delivery vehicles for osteogenic factors127,128. This dual function promotes stem cell adhesion, proliferation, and osteogenic differentiation, accelerating mineralized tissue formation. Huang et al. dispersed HA/SFNPs directly in silk solution to form a uniform HA/silk mixture. After freeze-drying process, composite scaffolds were formed. HA/SFNPs were uniformly distributed in silk scaffolds at nanometer scale129. Under the same HA content, the scaffolds loaded with HA/SFNPs showed significantly higher stiffness and better osteogenic properties. It is worth noting that the researchers only simply prepared HA/SFNPs composite scaffolds. SFNPs can be loaded with a variety of growth factors are not considered, and slow release rate of drugs from composite scaffolds may have important significance for bone tissue repair prospects. In addition, Wang et al. introduced a novel hierarchical drug delivery system, with micrometer-scale outer layer spheres composed of regenerated SF, characterized by connected porous structure through the n-butanol and regenerated SF combined emulsion route and freezing method. The system incorporates phenylboronic acid-enriched SFNPs, stabilized through chemical cross-linking, which encapsulate isoliquiritin derived from Glycyrrhiza uralensis. These nanoparticles promote complete penetration of the cartilage extracellular matrix, exhibit pH-responsive behavior, neutralize reactive oxygen species, and achieve controlled drug release, thereby reducing oxidative stress associated with cartilage degeneration and improving neuropathic hyperalgesia, with great potential in the treatment of early osteoarthritis130.

In skin wound healing, SFNPs have been embedded into hydrogels, sponges, and nanospray to provide sustained release of therapeutic agents and create a moist healing environment112. Studies have shown that SFNPs-based dressings accelerate re-epithelialization, angiogenesis, and extracellular matrix remodeling, while minimizing scar formation. For instance, Karaly et al. encapsulated Avicenna marina extract and neomycin into SFNPs, which exhibited not only antibacterial effects, but also antioxidant property and the ability to enhance cell proliferation131. Treatment with these SFNPs significant increases fibroblast proliferation and reduces inflammatory cells, indicating the potential in wound healing.

It is noteworthy that in antibacterial and wound-healing applications, SFNPs is commonly mixed into hydrogel-based systems, since SFNPs have no inherent antimicrobial capability, which can be endowed with potent antimicrobial properties through the load of antibiotics, or bioactive phytochemicals132. Such SFNPs hydrogels have been shown to accelerate the repair of full-thickness skin wounds by reducing bacterial colonization, enhancing angiogenesis, and promoting epidermal and dermal tissue regeneration. Moreover, SFNPs can be further functionalized with bioactive peptides, growth factors, or extracellular matrix-mimetic proteins to enhance cell adhesion, proliferation, and migration, while simultaneously imparting antibacterial and antioxidant functionalities to the material133,134. Karimi et al. prepared biocompatible and degradable hydrogel wound dressings based on carboxymethyl methyl chitosan/sodium carboxymethyl cellulose/agarose. SFNPs and dopamine-modified SFNPs were synthesized and loaded with ciprofloxacin and then incorporated into the hydrogel. The experiments demonstrated that appropriate physicochemical properties and cellular responses of the hydrogel containing nanoparticles supported fibroblast proliferation and growth135. Luo et al. prepared SFNPs loaded with milk fat globule EGF factor 8 (Fig. 6a–c), which accelerated skin vascular and pressure ulcer healing by targeting CD13 in vascular endothelial cells136 (Fig. 6d).

a Flow chart of composite nanoparticle synthesis. b, c SEM images and particle size distribution of NPs. d Wound photographs and Masson’ trichrome staining (Scale bar = 200 nm), along with RWD laser speckle imaging system to assess blood perfusion in wound tissue and adjacent normal tissue. Parts a–d reprinted with permission from ref. 136, BioMed Central.

Taken together, the multifaceted physicochemical properties and biofunctional capabilities of SFNP position them as highly versatile nanoplatforms for a broad spectrum of biomedical applications with significant translational potential in drug delivery and regenerative medicine.

Outlook

SFNPs possess excellent biocompatibility, enzymatic degradability, and low immunogenicity. SFNPs have been extensively validated in the delivery of small molecules, proteins/peptides, nucleic acids, and vaccine delivery for the treatment of various cancers, inflammatory diseases, and tissue damage. However, no silk fibroin nanoformulation has passed clinical trials, blocking its clinical transformation is a variety of aspects. The limitations in degumming and regeneration processes often lead to heterogeneous molecular weight distribution, fluctuations in β-sheet content, and residual solvents, which in turn affect particle size distribution, drug loading, and degradation rates. Such as residues of organic solvents during degumming may introduce new and unknown toxicities, and incomplete removal of sericin may cause immunogenic effects. Synthesis strategies for SFNPs have focused on the development of green, scalable, and controllable processes.

Microfluidics provides precise fluid control and repeatable mixing processes, and is an excellent route to high-throughput, monodisperse, and highly reproducible production, is a priority for SFNPs production. High-quality microfluidic chips (especially glass or silicon chips) and their associated precision syringe pumps, pressure controllers and observation systems are much more expensive than traditional methods (e.g. desolvation, self-assembly). And for scenarios that require large numbers of nanoparticles for in vivo animal experiments, clinical studies, or industrial production, it does not have an advantage in yield. Although microfluidic “numbering-up” strategies conceptually keep reaction conditions consistent, achieving parallel, stable, and non-differential operation of thousands of chip units is a huge engineering challenge and is still in the research stage. The current high cost of microfluidic chips is rooted in precision micromachining techniques such as lithography and etching. Multi-layer microfluidic chips are designed to integrate hundreds or even thousands of parallel reaction units on a single substrate, sharing uniform inlets and outlets. This greatly reduces the number and complexity of external connections. In addition, AI models are trained to predict system performance degradation (such as chip clogging, pump performance drift) using massive data collected by sensors and adjust in advance.

Furthermore, to achieve highly precise controlled release, SFNPs need to be engineered to overcome multiple physiological barriers simultaneously. Integrating multiple functional components, such as targeting ligands, stability enhancers, and therapeutic agents, into multifunctional systems inherently increases the burden of good manufacturing practice (GMP) compliance137. the regulatory authorities, including FDA, NMPA and European Medicines Agency (EMA), impose stringent requirements on in vitro-in vivo correlation validation, especially when introducing novel excipients or modified ligands. For example, SFNPs incorporating PEG coupling or tumor-targeting group need to be thoroughly characterized to ensure safety, consistency and traceability138.

As a novel biological nanocarrier system, SFNP formulations are classified as new drug delivery excipients, unlike bulk silk cellulose materials that have been approved for certain medical uses, and therefore must be subject to independent regulatory assessment139. The delivery system still faces a series of serious and specific challenges from laboratory to clinical transformation and large-scale industrialization. At present, SFNPs are prepared by various methods, but different laboratories or even different batches of preparation parameters in the same laboratory (e.g., temperature, stirring speed, solvent addition rate, fibroin concentration, and molecular weight) can cause significant differences in particle size, PDI, zeta potential, drug loading, and release kinetics of nanoparticles63. This batch-to-batch variation seriously hinders the reliability of preclinical studies and subsequent clinical trial submissions, and the lack of standard operating procedures (SOP) and online process analysis technology (PAT) monitoring makes it difficult for research results to be repeatedly verified by other teams, and the data comparability is poor, becoming a silent pain point in the field. In a word, efforts should be made to design scalable parallel microfluidic chip arrays and establish SOPs to support them, and promoting GMP compliant production procedures and preclinical evaluation. In particular, close collaboration between academia and pharmaceutical companies is required to establish GMP-compliant pilot production lines, thereby overcoming manufacturing challenges associated with the transition from laboratory to clinical application140,141.

Furthermore, SFNPs lack precise prediction and active manipulation of their fate in complex in vivo such as inflammatory and tumor tissue. How to effectively overcome reticuloendothelial system phagocytosis through surface modification (e.g. PEGylation, targeted peptide modification) and achieve active targeting rather than passive enrichment (EPR effect) remains a huge challenge142. No longer limited to synthetic polymer modifications (e.g. PEG), SFNPs are coated with red blood cell membranes, white blood cell membranes, or cancer cell membranes. Red blood cell membranes greatly extend circulation times; white blood cell membranes confer inflammatory targeting and ability to cross vascular barriers; cancer cell membranes facilitate homologous targeting and immune escape. This is a more advanced, biocompatible “active camouflage” strategy.

Ultimately, how to achieve sterility assurance of the final product (e.g. sterile filtration or gamma irradiation) without destroying the nanostructure is a specific engineering challenge. High production costs and complex production processes keep many potential SFNPs formulations at the thesis stage and fail to attract industry investment for subsequent development143. Based on the problems of aseptic production, the development of “total process control” and “alternative terminal sterilization” processes, in line with GMP standards in the clean area environment, the whole production process (including supramolecular self-assembly, purification) for full process sterility control, rather than final product sterilization. This requires a closed, automated continuous production system. Implement QbD (Quality by Design) philosophy and identify critical quality attributes of SFNPs at the beginning of development (e.g., particle size, Zeta potential, drug loading, release behavior), thereby reducing failures and waste in the production process and fundamentally controlling costs.

Collectively, although there are still obstacles in the clinical transformation process, SFNPs unique biological characteristics endow it with revolutionary potential and show remarkable broad application prospects.

Data availability

No data were used for the research described in the article.

References

-

Pham, D. T. & Tiyaboonchai, W. Fibroin nanoparticles: a promising drug delivery system. Drug Deliv. 27, 431–448 (2020).

-

Wang, D. & Lippard, S. J. Cellular processing of platinum anticancer drugs. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 4, 307–320 (2005).

-

Zhao, Z., Li, Y. & Xie, M. B. Silk fibroin-based nanoparticles for drug delivery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 16, 4880–4903 (2015).

-

Zhao, Z. et al. Fabrication of silk fibroin nanoparticles for controlled drug delivery. J. Nanopart. Res. 14, 736 (2012).

-

Wenk, E., Merkle, H. P. & Meinel, L. Silk fibroin as a vehicle for drug delivery applications. J. Control. Release 150, 128–141 (2011).

-

Totten, J. D., Wongpinyochit, T. & Seib, F. P. Silk nanoparticles: proof of lysosomotropic anticancer drug delivery at single-cell resolution. J. Drug Target 25, 865–872 (2017).

-

Ma, Y., Canup, B. S. B., Tong, X., Dai, F. & Xiao, B. Multi-responsive silk fibroin-based nanoparticles for drug delivery. Front Chem. 8, 585077 (2020).

-

Xu, H. L. et al. Silk fibroin nanoparticles dyeing indocyanine green for imaging-guided photo-thermal therapy of glioblastoma. Drug Deliv. 25, 364–375 (2018).

-

Yang, P. et al. Silk fibroin nanoparticles for enhanced bio-macromolecule delivery to the retina. Pharm. Dev. Technol. 24, 575–583 (2019).

-

Totten, J. D., Wongpinyochit, T., Carrola, J., Duarte, I. F. & Seib, F. P. PEGylation-dependent metabolic rewiring of macrophages with silk fibroin nanoparticles. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11, 14515–14525 (2019).

-

Seib, F. P., Jones, G. T., Rnjak-Kovacina, J., Lin, Y. & Kaplan, D. L. pH-dependent anticancer drug release from silk nanoparticles. Adv. Health. Mater. 2, 1606–1611 (2013).

-

Babonaitė, M., Striogaitė, E., Grigorianaitė, G. & Lazutka, J. R. In Vitro Evaluation of DNA Damage Induction by Silver (Ag), Gold (Au), Silica (SiO(2)), and Aluminum Oxide (Al(2)O(3)) Nanoparticles in Human Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 46, 6986–7000 (2024).

-

Park, K. et al. Injectable, long-acting PLGA formulations: analyzing PLGA and understanding microparticle formation. J. Control. Release 304, 125–134 (2019).

-

Shi, W. et al. Biodegradable polymeric nanoparticles increase risk of cardiovascular diseases by inducing endothelium dysfunction and inflammation. J. Nanobiotechnol. 21, 65 (2023).

-

Hong, S. et al. Protein-based nanoparticles as drug delivery systems. Pharmaceutics 12 (2020).

-

Mansor, M. H. et al. Efficient and rapid microfluidics production of bio-inspired nanoparticles derived from Bombyx mori silkworm for enhanced breast cancer treatment. Pharmaceutics 17, 95 (2025).

-

Pérez-Lloret, M. et al. Auranofin-loaded silk fibroin nanoparticles for colorectal cancer treatment. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 15, 1994–2008 (2025).

-

Belda Marín, C. et al. Silk polymers and nanoparticles: a powerful combination for the design of versatile biomaterials. Front. Chem. 8, 604398 (2020).

-

Qu, N. et al. Albumin nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems. Int. J. Nanomed. 19, 6945–6980 (2024).

-

Sultan, M. T. et al. Silk fibroin-based biomaterials for hemostatic applications. Biomolecules 12, 660(2022).

-

Zhang, X. et al. Self-reinforced silk nanofibrils networks enable ultrafine fibroin monofilament sutures applied in minimally invasive surgery. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 309, 142941 (2025).

-

Bucciarelli, A. & Motta, A. Use of Bombyx mori silk fibroin in tissue engineering: from cocoons to medical devices, challenges, and future perspectives. Biomater. Adv. 139, 212982 (2022).

-

Ferrera, F. et al. Silk fibroin nanoparticles for locoregional cancer therapy: Preliminary biodistribution in a murine model and microfluidic GMP-like production. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 282, 137121 (2024).

-

Harishchandra Yadav, R. et al. A review of silk fibroin-based drug delivery systems and their applications. Eur. Polym. J. 216, 113286 (2024).

-

Hassani Besheli, N. et al. Sustainable release of vancomycin from silk fibroin nanoparticles for treating severe bone infection in Rat Tibia Osteomyelitis Model. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 5128–5138 (2017).

-

Webborn, P. J. H., Beaumont, K., Martin, I. J. & Smith, D. A. Free drug concepts: a lingering problem in drug discovery. J. Med. Chem. 68, 6850–6856 (2025).

-

Jain, A., Singh, S. K., Arya, S. K., Kundu, S. C. & Kapoor, S. Protein nanoparticles: promising platforms for drug delivery applications. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 4, 3939–3961 (2018).

-

Shi, Y.-X., Zhu, Y.-J., Qian, Z.-G. & Xia, X.-X. Artificial spider silk materials: from molecular design, mesoscopic assembly, to macroscopic performances. Adv. Funct. Mater. 35, 2412793 (2025).

-

Long, D. et al. Genetic hybridization of highly active exogenous functional proteins into silk-based materials using “light-clothing” strategy. Matter 4, 2039–2058 (2021).

-

Mandal, B. B. & Kundu, S. C. A novel method for dissolution and stabilization of non-mulberry silk gland protein fibroin using anionic surfactant sodium dodecyl sulfate. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 99, 1482–1489 (2008).

-

Fan, R. et al. Anti-inflammatory peptide-conjugated silk fibroin/cryogel hybrid dual fiber scaffold with hierarchical structure promotes healing of chronic wounds. Adv. Mater. 36, 2307328 (2024).

-

Zhang, Y.-Q. et al. Formation of silk fibroin nanoparticles in water-miscible organic solvent and their characterization. J. Nanopart. Res. 9, 885–900 (2007). This study first reveals that peptide chains of regenerated Bombyx mori silk fibroin self-assemble in aqueous solution to form spherical nanoparticles with β-sheet crystalline structures and diameters ranging from 35 to 125 nanometers.

-

Cheng, G., Wang, X., Tao, S., Xia, J. & Xu, S. Differences in regenerated silk fibroin prepared with different solvent systems: from structures to conformational changes. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 132 (2015).

-

Atay, I. et al. Simple and green process for silk fibroin production by water degumming. ACS Omega 10, 272–280 (2025). This study reports a simple, environmentally friendly water-based degumming process that eliminates the need for salts such as lithium bromide, enabling the production of silk fibroin suitable for clinical translation.

-

Sánchez-Trasviña, C. et al. Silk fibroin nanoparticles as a drug delivery system of 3,3′-diindolylmethane with potential antiobesogenic activity. ACS Omega 9, 47661–47671 (2024).

-

Qi, Y. et al. A review of structure construction of silk fibroin biomaterials from single structures to multi-level structures. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18 (2017).

-

Wang, J. et al. Development and application of an advanced biomedical material-silk sericin. Adv. Mater. 36, 2311593 (2024).

-

Murphy, A. R., John, P. S. & Kaplan, D. L. Modification of silk fibroin using diazonium coupling chemistry and the effects on hMSC proliferation and differentiation. Biomaterials 29, 2829–2838 (2008).

-

Inoue, S. et al. Silk fibroin of bombyx mori is secreted, assembling a high molecular mass elementary unit consisting of H-chain, L-chain, and P25, with a 6:6:1 molar ratio*. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 40517–40528 (2000).

-

Rana, I. et al. A review on the use of composites of a natural protein, silk fibroin with Mxene/carbonaceous materials in biomedical science. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 278, 135101 (2024).

-

Kundu, B. et al. Silk proteins for biomedical applications: bioengineering perspectives. Prog. Polym. Sci. 39, 251–267 (2014).

-

Sofia, S., McCarthy, M. B., Gronowicz, G. & Kaplan, D. L. Functionalized silk-based biomaterials for bone formation. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 54, 139–148 (2001).

-

Panilaitis, B. et al. Macrophage responses to silk. Biomaterials 24, 3079–3085 (2003).

-

Dal Pra, I., Freddi, G., Minic, J., Chiarini, A. & Armato, U. De novo engineering of reticular connective tissue in vivo by silk fibroin nonwoven materials. Biomaterials 26, 1987–1999 (2005).

-

Cao, Y. & Wang, B. Biodegradation of silk biomaterials. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 10, 1514–1524 (2009).

-

Fernández-García, L. et al. Safety and tolerability of silk fibroin hydrogels implanted into the mouse brain. Acta Biomater. 45, 262–275 (2016).

-

Cebe, P. et al. Silk I and Silk II studied by fast scanning calorimetry. Acta Biomater. 55, 323–332 (2017).

-

Kratky, O., Schauenstein, E. & Sekora, A. A new type of lattice with large periods in silk. Nature 165, 527–528 (1950).

-

Drummy, L. F., Phillips, D. M., Stone, M. O., Farmer, B. L. & Naik, R. R. Thermally induced alpha-helix to beta-sheet transition in regenerated silk fibers and films. Biomacromolecules 6, 3328–3333 (2005).

-

Elgohary, D. H., Saad, M. A., Salem, M. M., Sherazy, E. H. & Khalifa, T. F. Assessment the properties of various surgical sutures. Sci. Rep. 15, 33330 (2025).

-

Muraleedharan, A., Acharya, S. & Kumar, R. Recent updates on diverse nanoparticles and nanostructures in therapeutic and diagnostic applications with special focus on smart protein nanoparticles: a review. ACS Omega 9, 42613–42629 (2024).

-

Mao, Y. et al. Correlation between protein features and the properties of pH-driven-assembled nanoparticles: control of particle size. J. Agric. Food Chem. 71, 5686–5699 (2023).

-

Long, S., Xiao, Y. & Zhang, X. Progress in preparation of silk fibroin microspheres for biomedical applications. Pharm. Nanotechnol. 8, 358–371 (2020).

-

Montalbán, M. G. et al. Production of curcumin-loaded silk fibroin nanoparticles for cancer therapy. Nanomaterials 8, 126 (2018).

-

Kundu, J., Chung, Y. I., Kim, Y. H., Tae, G. & Kundu, S. C. Silk fibroin nanoparticles for cellular uptake and control release. Int. J. Pharm. 388, 242–250 (2010).

-

Müller, B. G., Leuenberger, H. & Kissel, T. Albumin nanospheres as carriers for passive drug targeting: an optimized manufacturing technique. Pharm. Res. 13, 32–37 (1996).

-

Srisuwan, Y., Srihanam, P. & Baimark, Y. Preparation of silk fibroin microspheres and its application to protein adsorption. J. Macromol. Sci., Part A 46, 521–525 (2009).

-

Myung, S. J., Kim, H.-S., Kim, Y., Chen, P. & Jin, H.-J. Fluorescent silk fibroin nanoparticles prepared using a reverse microemulsion. Macromol. Res. 16, 604–608 (2008).

-

Yang, Y.-Y., Zhang, M., Liu, Z.-P., Wang, K. & Yu, D.-G. Meletin sustained-release gliadin nanoparticles prepared via solvent surface modification on blending electrospraying. Appl. Surf. Sci. 434, 1040–1047 (2018).

-

Niu, L. et al. The interactions of quantum dot-labeled silk fibroin micro/nanoparticles with cells. Materials 13, 3372 (2020).

-

Zhu, L. et al. Controlled electrospraying of sericin nanoparticles for enhancing the functional surface properties of polyester fabrics. Langmuir 41 (2025).

-

Qu, J. et al. Silk fibroin nanoparticles prepared by electrospray as controlled release carriers of cisplatin. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. Mater. Biol. Appl 44, 166–174 (2014).

-

Solomun, J. I., Totten, J. D., Wongpinyochit, T., Florence, A. J. & Seib, F. P. Manual versus microfluidic-assisted nanoparticle manufacture: impact of silk fibroin stock on nanoparticle characteristics. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 6, 2796–2804 (2020).

-

Nguyen, R. Y. et al. Tunable mesoscopic collagen island architectures modulate stem cell behavior. Adv. Mater. 35, 2207882 (2023).

-

Gao, Z. et al. Microfluidic-assisted ZIF-silk-polydopamine nanoparticles as promising drug carriers for breast cancer therapy. Pharmaceutics 15, 1811 (2023).

-

Lu, L. et al. Flow analysis of regenerated silk fibroin/cellulose nanofiber suspensions via a bioinspired microfluidic chip. Adv. Mater. Technol. 6, 2100124 (2021).

-

Zhang, Q. et al. Formation of protein nanoparticles in microdroplet flow reactors. ACS Nano 17, 11335–11344 (2023).

-

Matthew, S. A. L., Rezwan, R., Perrie, Y. & Seib, F. P. Volumetric scalability of microfluidic and semi-batch silk nanoprecipitation methods. Molecules 27, 2368 (2022).

-

Chen, Z., Lv, Z., Zhang, Z., Zhang, Y. & Cui, W. Biomaterials for microfluidic technology. Mater. Futures 1, 012401 (2022).

-

DeBari, M. K. et al. Silk fibroin as a green material. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 7, 3530–3544 (2021).

-

Lin, B. et al. Needle-plug/piston-based modular mesoscopic design paradigm coupled with microfluidic device for point-of-care pooled testing. Adv. Sci. 11, 2406076 (2024).

-

Pandey, V., Haider, T., Jain, P., Gupta, P. N. & Soni, V. Silk as a leading-edge biological macromolecule for improved drug delivery. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 55, 101294 (2020).

-

Sahoo, J. K., Hasturk, O., Falcucci, T. & Kaplan, D. L. Silk chemistry and biomedical material designs. Nat. Rev. Chem. 7, 302–318 (2023). This review summarizes recent advances in silk processing chemicals, modification mechanisms, and crosslinking strategies for designing silk fibroin and silk-based composite biomaterials, providing guidance for the systematic modification of silk fibroin.

-

Chen, J., Venkatesan, H. & Hu, J. Chemically modified silk proteins. Adv. Eng. Mater. 20, 1700961 (2018).

-

Sahoo, J. K. et al. Sugar functionalization of silks with pathway-controlled substitution and properties. Adv. Biol. 5, 2100388 (2021).

-

Hasturk, O., Sahoo, J. K. & Kaplan, D. L. Synthesis and characterization of silk ionomers for layer-by-layer electrostatic deposition on individual mammalian cells. Biomacromolecules 21, 2829–2843 (2020).

-

McGill, M., Grant, J. M. & Kaplan, D. L. Enzyme-mediated conjugation of peptides to silk fibroin for facile hydrogel functionalization. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 48, 1905–1915 (2020).

-

Bin, L. et al. Biodegradable silk fibroin nanocarriers to modulate hypoxia tumor microenvironment favoring enhanced chemotherapy. Front Bioeng. Biotechnol. 10, 960501 (2022).

-

Serban, M. A. & Kaplan, D. L. pH-Sensitive ionomeric particles obtained via chemical conjugation of silk with poly(amino acid)s. Biomacromolecules 11, 3406–3412 (2010).

-

Cai, K. et al. Poly(d,l-lactic acid) surfaces modified by silk fibroin: effects on the culture of osteoblast in vitro. Biomaterials 23, 1153–1160 (2002).

-

Cao, Y. et al. Drug release from core-shell PVA/silk fibroin nanoparticles fabricated by one-step electrospraying. Sci. Rep. 7, 11913 (2017).

-

Wang, S., Xu, T., Yang, Y. & Shao, Z. Colloidal stability of silk fibroin nanoparticles coated with cationic polymer for effective drug delivery. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 7, 21254–21262 (2015).

-

Pham, D. T., Saelim, N. & Tiyaboonchai, W. Alpha mangostin-loaded crosslinked silk fibroin-based nanoparticles for cancer chemotherapy. Colloids Surf. B: Biointerfaces 181, 705–713 (2019).

-

Xu, M. et al. Size-dependent in vivo transport of nanoparticles: implications for delivery, targeting, and clearance. ACS Nano 17, 20825–20849 (2023).

-

Ma, N. et al. Influence of nanoparticle shape, size, and surface functionalization on cellular uptake. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 13, 6485–6498 (2013).

-

Balog, S., de Almeida, M. S., Taladriz-Blanco, P., Rothen-Rutishauser, B. & Petri-Fink, A. Does the surface charge of the nanoparticles drive nanoparticle–cell membrane interactions? Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 87, 103128 (2024).

-

Lammel, A. S., Hu, X., Park, S.-H., Kaplan, D. L. & Scheibel, T. R. Controlling silk fibroin particle features for drug delivery. Biomaterials 31, 4583–4591 (2010).

-

Niu, L. et al. Polyethylenimine-modified Bombyx mori silk fibroin as a delivery carrier of the ING4-IL-24 coexpression plasmid. Polymers 13, 3592(2021).

-

Xing, X., Han, Y. & Cheng, H. Biomedical applications of chitosan/silk fibroin composites: a review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 240, 124407 (2023).

-

Zou, X., Jiang, Z., Li, L. & Huang, Z. Selenium nanoparticles coated with pH-responsive silk fibroin complex for fingolimod release and enhanced targeting in thyroid cancer. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 49, 83–95 (2021).

-

Gou, S., Huang, Y., Sung, J., Xiao, B. & Merlin, D. Silk fibroin-based nanotherapeutics: application in the treatment of colonic diseases. Nanomedicines 14, 2373–2378 (2019). This study develops silk fibroin nanoparticles as a multifunctional nanotherapeutic platform, enabling combined phototherapy for cancer treatment.

-

Gou, S. et al. Multi-responsive nanotheranostics with enhanced tumor penetration and oxygen self-producing capacities for multimodal synergistic cancer therapy. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 12, 406–423 (2022).

-

Liu, J., Zhou, Y., Lyu, Q., Yao, X. & Wang, W. Targeted protein delivery based on stimuli-triggered nanomedicine. Exploration 4, 20230025 (2024).

-

Ma, Y. et al. Oral nanotherapeutics based on Antheraea pernyi silk fibroin for synergistic treatment of ulcerative colitis. Biomaterials 282, 121410 (2022). This study reports that Antheraea pernyi silk nanoparticles exhibite targeting capability and multi-responsive drug release behavior, enabling modulation of inflammatory microenvironments.

-

Wongpinyochit, T., Johnston, B. F. & Seib, F. P. Degradation behavior of silk nanoparticles—enzyme responsiveness. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 4, 942–951 (2018). This study provides the first insights into the proteolytic susceptibility of silk nanoparticles in target cells, with important implications for their targeted modification and responsive release.

-

Qian, Z. et al. Unravelling the antioxidant behaviour of self-assembly β-Sheet in silk fibroin. Redox Biol. 76, 103307 (2024).

-

Wu, J. et al. Oral delivery of curcumin using silk nano- and microparticles. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 4, 3885–3894 (2018).

-

Pham, D. T. et al. PEGylated silk fibroin nanoparticles for oral antibiotic delivery: insights into drug–carrier interactions and process greenness. ACS Omega 10, 11627–11641 (2025).

-

Nomani, A., Yousefi, S., Sargsyan, D. & Hatefi, A. A quantitative MRI-based approach to estimate the permeation and retention of nanomedicines in tumors. J. Control Release 368, 728–739 (2024).

-

Nguyen, L. N. M. et al. The mechanisms of nanoparticle delivery to solid tumours. Nat. Rev. Bioeng. 2, 201–213 (2024).

-

Belyaev, I. B., Griaznova, O. Y., Yaremenko, A. V., Deyev, S. M. & Zelepukin, I. V. Beyond the EPR effect: intravital microscopy analysis of nanoparticle drug delivery to tumors. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 219, 115550 (2025).

-

Li, Z. et al. PX478-loaded silk fibroin nanoparticles reverse multidrug resistance by inhibiting the hypoxia-inducible factor. Int J. Biol. Macromol. 222, 2309–2317 (2022).

-

Varma, S., Dey, S. & Palanisamy, D. Cellular uptake pathways of nanoparticles: process of endocytosis and factors affecting their fate. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 23, 679–706 (2022).

-

Pham, D. T. et al. Silk fibroin nanoparticles as a versatile oral delivery system for drugs of different biopharmaceutics classification system (BCS) classes: a comprehensive comparison. J. Mater. Res. 37, 4169–4181 (2022).

-

Zhu, J. et al. Cellular interactions and biological effects of silk fibroin: implications for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. Small 21, 2409739 (2025).

-

Wong, K., Tan, X. H., Li, J., Hui, J. H. P. & Goh, J. C. H. An in vitro macrophage response study of silk fibroin and silk fibroin/nano-hydroxyapatite scaffolds for tissue regeneration application. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 10, 7073–7085 (2024).

-

Cui, X. et al. A pilot study of macrophage responses to silk fibroin particles. J. Biomed. Mater. Res A 101, 1511–1517 (2013).

-